Abstract

Gender and sexually diverse adolescents have been reported to be at an elevated risk for suicidal thoughts and behaviors. For transgender adolescents, there has been variation in source of ascertainment and how suicidality was measured, including the time-frame (e.g., past 6 months, lifetime). In studies of clinic-referred samples of transgender adolescents, none utilized any type of comparison or control group. The present study examined suicidality in transgender adolescents (M age, 15.99 years) seen at specialty clinics in Toronto, Canada, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, and London, UK (total N = 2771). Suicidality was measured using two items from the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and the Youth Self-Report (YSR). The CBCL/YSR referred and non-referred standardization samples from both the U.S. and the Netherlands were used for comparative purposes. Multiple linear regression analyses showed that there was significant between-clinic variation in suicidality on both the CBCL and the YSR; in addition, suicidality was consistently higher among birth-assigned females and strongly associated with degree of general behavioral and emotional problems. Compared to the U.S. and Dutch CBCL/YSR standardization samples, the relative risk of suicidality was somewhat higher than referred adolescents but substantially higher than non-referred adolescents. The results were discussed in relation to both gender identity specific and more general risk factors for suicidality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Across the life-span, transgender people, including those with a diagnosis of gender dysphoria (GD), have been shown to report more mental health problems, on average, than non-clinical cisgender people (for reviews on adults, see [1,2,3,4]). In baseline assessment studies on mental health problems in clinic-referred samples, both children and adolescents with GD show rates of difficulties that are, on average, at least comparable in degree to that of clinical controls (for reviews, see [5,6,7,8,9]).

In the literature on lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) youth, there is frequent reference to an elevated rate of suicidality (in both thoughts and behaviors) (e.g., [10,11,12,13,14]). In recent years, empirical research has also examined the risk of suicidality among adolescents with GD, which has received a considerable amount of media attention, as occurred, for example, after the suicide of U.S. transgender teen Leelah Alcorn in December 2014, putatively related to the parent’s non-acceptance of her female gender identity [15]).Footnote 1

Studies of suicidality among adolescents who self-identify as transgender (or some alternative gender different from the assigned gender at birth) or who have been diagnosed with GD include non-representative community samples, representative samples of high school students, and samples from specialized gender identity clinics. In these studies, suicidality has been measured in different ways, including (1) self-report of suicidal ideation, (2) self-harming behavior, and (3) suicide attempts in response to specific questions, with different time frames (e.g., in the past 2 weeks, life-time) or via coding of case file information in clinical samples.

In an early study, based on data collected between 2001 and 2003, Grossman and D’Augelli [22] recruited a convenience sample of 55 self-identified 15–21-year-old transgender adolescents from two social and recreation service agencies for LGBT adolescents in New York City. A total of 45% reported that they had “seriously thought” about suicide and 26% reported a suicide attempt. In a more recent study, based on data collected in 2013–2014, Veale et al. [23] sampled 199–231 14–18-year-old Canadian adolescents (80% birth-assigned females) who self-identified as “trans.” Source of recruitment varied, including transgender and “queer” community groups, social media sites, and pediatric endocrinology clinics. A comparison group consisted of 29,832 14–18-year-old adolescents from the 2013 British Columbia Adolescent Health Survey (BCAHS) who were sampled from randomly selected high school classrooms. In the trans sample, 65% reported suicidal ideation in the past year compared to 13% in the BCAHS; the corresponding percentages for self-harm and suicide attempts in the past year were 75% vs. 17% and 36% vs. 7%, respectively.Footnote 2 In another study, Toomey et al. [24] sampled 377 transgender and 118,844 male and female high school students who participated in the U.S.-based Profiles of Student Life: Attitudes and Behavior Study between 2012 and 2015. Students were asked if they had ever tried to kill themselves, with response options of either No or Yes (once, twice or more than two times). For the birth-assigned female transgender students (n = 175), the percentage who answered “Yes” was 50.8%, which was notably higher than the 17.6% of the female control students (n = 60,973); of the birth-assigned male transgender students (n = 202), 29.9% answered “Yes” compared to 9.8% of the male control students (n = 57,871) (for a similar study, see Thoma et al. [25]).

Suicidality information obtained in non-representative samples should, of course, be viewed with some caution because the participants may not be representative of all adolescents who self-identify as transgender or some alternative gender, which could result in either under- or over-estimates of prevalence. In recent years, there have been several, large-scale studies on suicidality drawn from representative samples of high school students. In two studies, self-reported suicidal ideation over the past 12 months for transgender students was 33.7% (total n = 280) [26] and 43.9% (total n = 2273) [27]; M. M. Johns, personal communication, December 23, 2019] compared to 18.8% (n = 25,213) and 15.7% (n = 97,810), respectively, of the non-transgender students.Footnote 3 In two studies, self-reported self-harm over the past 12 months for transgender students was 45.3% (total n = 95) [29] and 55.0% (total n = 1941) [30] L. A. Taliaferro, personal communication, December 20, 2019] compared to 23.4% (total n = 7710) and 14.3% (total n = 74,134) for the non-transgender students, respectively.Footnote 4 For self-reported suicide attempts over the past 12 months, the percentage for the transgender students was 19.8% in Clark et al. [29] and 34.6% (n = 1069) in Johns et al. [27] compared to 4.1% and 7.4% (n = 67,711), respectively, in the non-transgender students. In Taliaferro et al. [31], the percentage of transgender students (total n = 1635) who reported both self-harm and a suicide attempt over the past 12 months was 18.0%.

To date, there have been at least 17 studies that have reported on suicidality among clinic-referred adolescents with GD (see Appendix). As shown in the Appendix, the sample sizes ranged from 31 to 1082, with a median of 78. Most of these studies ascertained rates of suicidality over the client’s lifetime, with fewer studies using a “current” or more recent timeframe. Not surprisingly, almost all the studies found higher rates of suicidal ideation than suicidal behaviors. For example, Nahata et al. [42] reported a lifetime prevalence of 74.7% for suicidal ideation compared to a lifetime prevalence of 30.4% for suicide attempts. In contrast, Moyer et al. [47] reported a prevalence of 35.9% for suicidal ideation for the 2 weeks prior to the assessment and Becker et al. [34] reported a prevalence of 11.8% for “current” suicide attempts.

Explanations for suicidality risk

Several reasons for this apparent elevation in suicidality among transgender adolescents have been considered. One explanation is that GD is inherently distressing, which leads to suicidal thoughts and/or behaviors [9]. A second possibility is that an elevation in suicidality is the direct result of social stigma, such as social ostracism within the peer group or within-family rejection due to the expression of gender-variant behavior, as posited by minority stress theory (e.g., [64,65,, 65]). Indeed, there is evidence that gender-variant behavior per se is associated with suicidality risk in adolescents, even after controlling for confounding factors such as sexual orientation [66]. Lastly, a third possibility is that such thoughts and behaviors are related to more general behavioral and emotional problems, which could increase the vulnerability for suicidality. These more general problems could be related to generic risk factors, such as an underlying biological vulnerability or psychosocial family processes (e.g., [67,68,69]), unrelated to GD per se.

Current study

Although the clinic-based studies certainly suggest an elevated rate of suicidal ideation and behaviors, there are two important limitations to the extant findings: non-clinical comparison groups were almost never employed and, more importantly, a clinical comparison group was not employed in any of the specialized gender identity clinic samples. Thus, there is a compelling need to document how rates of suicidality in adolescents referred for GD compare to (mental health) clinical controls and non-clinical controls.

There are two exceptions, both of which consisted of transgender adolescents seen clinically, but not in specialized gender identity clinics: the study by Becerra-Culqui et al. [43] consisted of adolescent patients (defined as ages 10–17 years) seen at one of three Kaiser Permanente healthcare sites in the U.S. and classified as “transgender” or “gender-nonconforming” (n = 1082) based on ICD-9 codes any time between 2006 and 2014. Becerra-Culqui et al. examined suicidal ideation and behavior for two time periods (at any time prior to the date of assessment and 6 months before the date of assessment). Compared to 10,654 reference males (10 per proband) and 10,662 females (10 per proband) (matched on the basis of several variables, such as year of birth, site, etc.) who were seen for any other reason other than gender identity (i.e., for either mental health or physical health issues), prevalence ratio estimates for both suicidal ideation and behavior were substantially higher in the transgender/gender-nonconforming group (see Becerra-Culqui et al. [43], Table 3]). In Becerra-Culqui et al., however, it is not clear what percentage of the referent group adolescents were being seen for mental health vs. non-mental health reasons. In general, then, there is a clear need to document how rates of suicidality in adolescents referred for GD compare to (mental health) clinical controls and non-clinical controls.

The other study by Bettis et al. [50] consisted of 31 transgender adolescents admitted to a psychiatric inpatient unit in 2017 or 2018 who were compared to 473 cisgender males and females (consisting of both heterosexual and non-heterosexual youth) admitted to the same unit. Compared to the cisgender youth, Bettis et al. found that the transgender youth had a significantly higher score on a past-month dimensional measure of suicidal ideation but did not differ significantly on measures of non-suicidal self-injury and suicide attempts. Thus, this study found mixed evidence for a higher rate of suicidality among transgender youth compared to a clinical comparison group; of course, because the sample consisted of adolescents admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit, the generality of the findings to transgender youth in general should be done with caution.

The aim of the present study, therefore, was to assess systematically the prevalence of suicidal thoughts and behaviors from three clinic-referred samples of adolescents with GD—from Toronto (Ontario, Canada), Amsterdam (the Netherlands), and London (UK)—by both parent-report and self-report. We used a metric of suicidality by extracting two items from two standardized behavior problem questionnaires—the parent-report Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and the Youth Self-Report (YSR). We tested for cross-national differences in suicidality between the three clinics. In addition, we tested for other correlates of suicidality, including demographic variables (e.g., birth-assigned sex, age at assessment, and year of assessment), poor peer relations, and number of behavioral and emotional problems in general. In addition, and to address the matter of specificity [70], we also compared the percentage of adolescents with GD who, either by parent-report or self-report, endorsed suicidality with the CBCL/YSR referred and non-referred standardization samples from the U.S. and the Netherlands. Use of the standardization samples allowed us to test for the specificity of suicidality among adolescents with GD vs. a characteristic of clinic-referred adolescents in general, which would be an example of equifinality [71] (see also Garber and Hollon [70]).

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 2771 adolescents (age 13 years or older; M age, 15.99 years; SD = 1.20) referred and assessed for GD at one of three clinic sites between 1978 and 2017 (M year of assessment, 2013.06; SD = 5.21): the Gender Identity Service at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) in Toronto, Ontario (n = 260); the Center of Expertise on Gender Dysphoria at the Amsterdam University Medical Centers, VUmc site in Amsterdam, the Netherlands (n = 266), and the Gender Identity Development Service at the Tavistock and Portman National Health Service Trust in London, UK (n = 2245).Footnote 5 As shown in Table 1, the London cohort consisted of adolescents assessed, on average, in more recent years and the disproportionate number of cases from this clinic reflects the marked increase in adolescents referred for GD during this period of time [73,74,75]. By clinician interview, all adolescents met DSM-III, DSM-III-R, DSM-IV or DSM-5 criteria either for Gender Identity Disorder/Gender Dysphoria or Gender Identity Disorder Not Otherwise Specified.Footnote 6

Measures

Demographics

Six demographic variables were coded: (1) birth-assigned sex; (2) age at assessment; (3) year of assessment; (4) Full-Scale IQ; (5) parents’ marital status; and (6) parents’ social class (Table 1). We assessed IQ using the American or Dutch versions of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children or the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (IQ data were not available for the London clinic adolescents). Marital status of the parents was categorized as either living with both biological parents (or with adoptive parents from birth) or all other categories (e.g., single parent, separated, divorced, widowed, reconstituted, living in a group home, etc.). Parents’ social class was categorized using the method described in Cohen-Kettenis et al. [76]. In the Toronto clinic, the Hollingshead’s [77] Four-Factor Index of Social Status was used, classifying individuals on a five-point scale ranging from I (major business and professional) to V (unskilled laborers, menial service workers). In the Amsterdam clinic, a 5-point scale was used for both parents, where 1 = university degree and 5 = Grade 8 (primary school or less). To make these two methods of assessment comparable, the Hollingshead's ratings for the Toronto sample were coded where a social class ranking of I = 1, II–III = 2, and IV–V = 3. For the Amsterdam sample, an education rating (averaged across both parents) was coded as 1.0–2.0 = 1, 2.5–3.5 = 2, and 4.0–5.0 = 3. Parents’ marital status and social class were not available for the London clinic adolescents.

Suicidality

We used Items 18 and 91 from the CBCL [78] and the YSR [72] to measure suicidality. Item 18 reads as “Deliberately harms self or attempts suicide” (CBCL) or “I deliberately try to hurt or kill myself” (YSR); Item 91 reads as “Talks about killing self” (CBCL) or “I think about killing myself” (YSR). Like all CBCL/YSR items, they were rated on a 3-point response scale, where 0 = not true, 1 = somewhat or sometimes true, and 2 = very true or often true. The parent or adolescent was asked to make such ratings for “now or within the past 6 months.” For the Dutch adolescents, the Dutch translations of the CBCL and YSR were used [79, 80]. For both the CBCL and YSR, we calculated a simple sum score of the two items or dichotomized each item as either present (rated as a 1 or a 2) or absent (rated as a 0). Based on the 2001 CBCL and YSR U.S. standardization sample and the Dutch standardization sample, it seemed reasonable to create a composite score: the within-scale correlation between the two suicidality items ranged between 0.39 and 0.62 for referred males and females and between − 0.00 and 0.46 for non-referred males and females (7/8 correlations significant at p < 0.001). For the Dutch CBCL and YSR standardization samples, the within-scale correlations between the two suicidality items ranged between 0.40-0.63 for referred males and females and between −0.00 and −0.69 for non-referred males and females (7/8 correlations significant at p < 0.001). The two non-significant correlations were likely due to floor effects (see also Van Meter et al. [81]).Footnote 7

In the present study, we calculated the correlation between the CBCL and YSR suicidality sum score as a function of clinic and birth-assigned sex. In the Toronto sample, the correlation for the birth-assigned males (r = 0.12) was not significant, but was significant for the birth-assigned females (r = 0.52, p < 0.001). In the Amsterdam sample, the correlation for the birth-assigned males (r = 0.61) and birth-assigned females (r = 0.63) were both significant, ps < 0.001. In the London sample, the correlation for the birth-assigned males (r = 0.02) and birth-assigned females (r = 0.07) were both not significant. This variation in parent–youth concordance for suicidality provides good reason to analyze the CBCL and YSR data separately rather than combining ratings across the parent and youth.

Other CBCL and YSR Metrics

From the CBCL and YSR, we coded three other metrics: (1) the percentage of cases in which the CBCL/YSR Item 110 (“Wishes to be of opposite sex”/ “I wish I were of the opposite sex”) was rated as a 1 or a 2; (2) a Poor Peer Relations scale (Items 25, 38, and 48) (for details, see Zucker et al. [82]), and (3) a sum behavior problem score of all items rated as a 1 or a 2 (minus the sum of the two suicidality items, the sum of the poor peer relations items, and the gender identity item).

Procedure

Since the year 2000, the Toronto and Amsterdam clinics have recommended puberty suppression treatment (GnRH analogues) for about two-thirds of the referred adolescents (see Cohen-Kettenis et al. [83] and Zucker et al. [84]), but only after completion of the baseline assessment. In the London clinic, puberty suppression could be recommended, when appropriate, during the years of data collection (see Costa et al. [85]). In all three clinics, demographic information and the other measures used in this study were obtained at the time of a baseline assessment, i.e., prior to any hormonal treatment for GD.

Statistical Analysis

For the demographic and CBCL/YSR data, we compared the adolescents from the three clinics using either parametric or non-parametric statistics. In addition, we provide comparative analyses using the referred and non-referred CBCL and YSR U.S. and Dutch standardization samples. For the U.S. standardization data, two data sets were available: the 1991 standardization sample and the 2001 standardization sample [72, 86]. For completeness, we provide relevant information from both of these samples. However, we will use the 2001 standardization data for the narrative comparisons described below for two reasons: these data were collected closer to the mean year of assessment of the adolescents with GD (see Table 1) and because we were able to remove from this sample the referred and non-referred adolescents for whom Item 110 on the CBCL and YSR was rated as a 1 or a 2. Unfortunately, it was not possible to do this for the earlier U.S. standardization sample. For the Dutch standardization sample, we used new data reported on by Tick, van der Ende, and Verhulst [87, 88]. We calculated risk ratios for suicidality to compare the rate between the gender-dysphoric adolescents and the referred and non-referred adolescents in the standardization samples. We then conducted multiple linear regression analyses (with pairwise deletion) to identify whether there were any predictors of suicidality on the CBCL and the YSR in the data set.

Results

Demographic and General Child Behavior Checklist/Youth Self-Report Metrics

Table 1 shows the demographic variables as a function of clinic. On average, the Toronto clinic adolescents were significantly older than both the Amsterdam and London clinic adolescents. The percentage of birth-assigned females in the London clinic was significantly higher than the percentage in the Toronto and Amsterdam clinics. As noted earlier, the year of assessment for the London clinic adolescents was, on average, significantly more recent than both the Toronto and Amsterdam adolescents. For IQ, social class, and parent’s marital status, data were available only from the Toronto and Amsterdam clinics. On average, the adolescents from the Toronto clinic had a significantly higher IQ than the adolescents from the Netherlands but did not differ significantly with regard to parent’s social class or marital status.

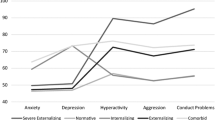

With regard to the sum of all behavior problems on the CBCL and YSR, there were significant between-clinic differences. On the CBCL, the adolescents from the Toronto clinic had, on average, more behavior problems than the adolescents from the London clinic who, in turn had more behavior problems than the adolescents from the Amsterdam clinic. On the YSR, the adolescents from the London clinic had, on average, more behavior problems than the adolescents from the Toronto clinic who, in turn, had more behavior problems than the adolescents from the Amsterdam clinic. On the CBCL (poor) peer relations scale, the adolescents from the Toronto clinic had, on average, a higher score than the adolescents from both the Amsterdam and the London clinic. On the YSR (poor) peer relations scale, the adolescents from the Toronto clinic and the London clinic had, on average, a higher score than the adolescents from the Amsterdam clinic. For the CBCL gender identity item, the percentage of adolescents from the London clinic who received a rating of a 1 or a 2 was significantly higher than the percentage of adolescents from the Toronto and Amsterdam clinics, although in all clinics the percentage was ≥ 93%. On the YSR, the between-clinic difference was not significant, with all percentages ≥ 95%.

Suicidality

Child Behavior Checklist (parent-report)

For the suicidality composite based on parent-report, the adolescents from the Toronto and London clinics had, on average, a higher score than the adolescents from the Amsterdam clinic (Table 1). Table 2 shows the percentage of the adolescents from the Toronto, Amsterdam, and London clinics, by birth-assigned sex, whose parents (predominately mothers) rated the two CBCL suicidality items as either a 1 or a 2. Table 2 also shows the percentages for both referred and non-referred adolescents in the U.S. and Dutch standardization samples. Across the three clinics, endorsement of Item 91 (suicidal ideation) ranged from 22.4 to 39.2% and endorsement of Item 18 (suicidal behavior) ranged from 8.6 to 50.8%.

Table 2 also shows the percentage of parents who rated the two CBCL suicidality items as either a 1 or a 2 in the U.S. (2001) and Dutch standardization samples, by birth-assigned sex, for referred and non-referred adolescents, respectively. For the referred samples, endorsement of Item 91 (suicidal ideation) ranged from 17.9 to 34.9% and endorsement of Item 18 (suicidal behavior) ranged from 7.7 to 31.1%. For the non-referred samples, endorsement of Item 91 ranged from 1.4 to 2.7% and endorsement of Item 18 ranged from 0.6 to 1.8%.

Youth Self-Report

For the suicidality composite based on self-report, the adolescents from the London clinic had, on average, a higher score than the adolescents from the Toronto clinic who, in turn, had a higher score than the adolescents from the Amsterdam clinic (Table 1). Table 2 shows the percentage of the adolescents from the Toronto, Amsterdam, and London clinics, by birth-assigned sex, who rated the two YSR suicidality items as either a 1 or a 2. Table 2 also shows the percentages for both referred and non-referred adolescents in the U.S. and Dutch standardization samples. Across the three clinics, endorsement of Item 91 (suicidal ideation) ranged from 27.3 to 55.3% and endorsement of Item 18 suicidal behavior) ranged from 14.5 to 45.2%.

Table 2 also shows the percentage of adolescents who rated the two YSR suicidality items as either a 1 or a 2 in the 2001 U.S. and Dutch standardization samples, by birth-assigned sex, for referred and non-referred adolescents, respectively. For the referred samples, endorsement of Item 91 (suicidal ideation) ranged from 14.4 to 31.2% and endorsement of Item 18 (suicidal behavior) ranged from 7.5 to 24.3%. For the non-referred samples, endorsement of Item 91 ranged from 1.5 to 7.7% and endorsement of Item 18 ranged from 2.2 to 3.9%.

Relative risk between the three clinic samples and the referred and non-referred standardization samples

When the percentage data from the three clinics were compared to the percentage data in the referred and non-referred standardization samples, it was apparent that the percentages were relatively similar to the referred samples, but markedly higher than the non-referred samples. Table 3 provides a comparative analysis of these data. Of 24 comparisons with the referred standardization sample, there were 21 instances in which the percentage was higher among the transgender adolescents.

In the Toronto clinic, the relative risk on the CBCL and YSR suicidality items, when compared to the referred samples, ranged from around parity (e.g., 0.93:1 for the birth-assigned female transgender adolescents vs. referred females for CBCL Item 91) to 2.86:1 (birth-assigned male transgender adolescents vs. referred males for YSR Item 91). When compared to the non-referred sample, the range was between 5.19:1 (birth-assigned female transgender adolescents vs. non-referred females for YSR Item 91) and 48.66:1 (birth-assigned male transgender adolescents vs. non-referred males for CBCL Item 18). For example, for CBCL Item 91, the birth-assigned male transgender adolescents were 1.71 times more likely to express suicidal ideation compared to the referred males in the standardization sample but 28 times more likely to express suicidal ideation compared to the non-referred males in the standardization sample. Referred males in the standardization sample were 16.35 times more likely to express suicidal ideation compared to the non-referred males.

In the Amsterdam clinic, the relative risk of the difference on the CBCL and YSR suicidality items, when compared to the referred samples, ranged from 0.97:1 (birth-assigned female transgender adolescents vs. referred females for CBCL Item 18) to 1.93:1 (birth-assigned male transgender adolescents vs. referred males for YSR Item 18). When compared to the non-referred sample, the range was between 6.34:1 (birth-assigned female transgender adolescents vs. non-referred females for YSR Item 91) and 28.66:1 (birth-assigned male transgender adolescents vs. non-referred males for CBCL Item 18). For example, for CBCL Item 91, the birth-assigned male transgender adolescents were 1.25 times more likely to express suicidal ideation compared to the referred males in the standardization sample but 9.33 times more likely to express suicidal ideation compared to the non-referred males in the standardization sample. Referred males from the standardization sample were 7.45 times more likely to express suicidal ideation compared to the non-referred males.

In the London clinic, the relative risk on the CBCL and YSR suicidality items, when compared to the referred samples, ranged from 1.48:1 (birth-assigned female transgender adolescents vs. referred females for CBCL Item 91) to 5.50:1 (birth-assigned transgender males vs. referred males for YSR Item 18). When compared to the non-referred sample, the range was between 11.00:1 (birth-assigned male transgender adolescents vs. non-referred males for CBCL Item 18) and 32.73:1 (birth-assigned male transgender adolescents vs. non-referred males for YSR Item 91). For example, for CBCL Item 91, the birth-assigned male transgender adolescents were 5.50 times more likely to express suicidal ideation compared to the referred males in the standardization sample but 18.77 times more likely to express suicidal ideation compared to the non-referred males in the standardization sample.

Predictors of Suicidality: Multiple Regression Analyses

To examine predictors of suicidality for the transgender adolescents, we performed multiple linear regression analysis separately for the CBCL and YSR data, contrasting the three clinics (Toronto vs. Amsterdam, Toronto vs. London, and Amsterdam vs. London). For the Toronto vs. Amsterdam contrasts, there were nine predictor variables: clinic, birth-assigned sex, year of assessment, age at assessment, full-scale IQ, parent’s marital status, parent’s social class, poor peer relations, and the sum of all other behavioral and emotional problems (minus the three items from the poor peer relations scale, the two suicidality items, and the gender identity item). For the Toronto vs. London and Amsterdam vs. London contrasts, there were six predictor variables: clinic, birth-assigned sex, year of assessment, age at assessment, poor peer relations, and the sum of all other behavioral and emotional problems. The criterion variable was the sum of the two suicidality items.

Child Behavior Checklist

Tables 4, 5, 6 show the results for the three contrasts. For the Toronto–Amsterdam contrast (Table 4), there were five significant predictors: clinic, birth-assigned sex, parent’s marital status, parent’s social class, and general behavioral and emotional problems (year of assessment had a p value of 0.056). The adolescents from the Toronto clinic had higher reports of suicidality than the adolescents from the Amsterdam clinic. A higher degree of suicidality was also associated with birth-assigned female transgender adolescents, adolescents who lived in a family configuration classified as “Other” (see Table 1), a lower social class background, and more behavioral and emotional problems in general. For the Toronto–London contrast (Table 5), there were three significant predictors: clinic, birth-assigned sex, and general behavioral and emotional problems. The adolescents from the London clinic had a higher degree of suicidality than the adolescents from the Toronto clinic. A higher degree of suicidality was also associated with birth-assigned female transgender adolescents and more behavioral and emotional problems in general. For the Amsterdam–London contrast (Table 6), there were three significant predictors: clinic, birth-assigned sex, and general behavioral and emotional problems. The adolescents from the London clinic had higher reports of suicidality than the adolescents from the Amsterdam clinic. A higher degree of suicidality was also associated with birth-assigned female adolescents and more behavioral and emotional problems in general.

Youth Self-Report

Tables 7, 8, 9 show the results for the three contrasts. For the Toronto–Amsterdam contrast (Table 7), clinic was not significant, but three other predictors were significant: birth-assigned sex, poor peer relations, and general behavioral and emotional problems. A higher degree of suicidality was associated with birth-assigned female transgender adolescents, poor peer relations, and more behavioral and emotional problems in general. For the Toronto–London contrast (Table 8), there were two significant predictors: clinic and general behavioral and emotional problems. The adolescents from the London clinic had higher reports of suicidality than the adolescents from the Toronto clinic and a higher degree of suicidality was also associated with more behavioral and emotional problems in general. For the Amsterdam–London contrast (Table 9), there were two significant predictors: clinic and general behavioral and emotional problems. The adolescents from the London clinic reported a higher degree of suicidality than the adolescents from the Amsterdam clinic and a higher degree of suicidality was also associated with more behavioral and emotional problems in general.

Discussion

Using a two-item, continuous composite measure of suicidality derived from the CBCL and YSR, the multiple regression analyses showed significant between-clinic effects for five of the six contrasts, even with all of the other predictors entered into the equations controlled for. This between-clinic variation (by birth-assigned sex) can also be seen in the descriptive data shown in Table 2 for both suicidality items on the CBCL and YSR. That there was some between-clinic variation is consistent with other clinic-based studies listed in the Appendix. For example, across four studies that assessed suicidal ideation “currently” [34, 43, 47,48,49] the percentages ranged from 6.2 [43] to 42.2% [34]. Similarly, across eight studies that assessed “lifetime” suicide attempts [33, 35, 36, 38,39,40, 42, 48, 49], the percentages ranged from 14 [48] to 30.4% [42], not including the inpatient sample of Bettis et al. [50].

Notwithstanding the between-clinic variation, it was apparent that the transgender adolescents from the three clinics were all somewhat higher in their suicidality rate when compared to the refered adolescents in the standardization samples and, more importantly, substantially higher than the non-referred adolescents. Whereas prior clinic-based studies on suicidality lacked any type of comparison group of adolescents, our use of the CBCL and YSR standardization data allowed us to put the suicidality data in a comparative perspective. From the risk ratio analyses (Table 3), this finding is consistent with various studies which show that adolescents diagnosed with GD have, on average, a greater number of behavioral and emotional problems in general when compared to non-referred adolescents, but relatively similar to adolescents seen clinically for other types of mental health issues [89,90,91,92].

Apart from between-clinic effects, the multiple regression analyses included eight (for the Toronto–Amsterdam contrasts) or five other predictor variables (for the Toronto–London and Amsterdam–London contrasts). Of these, birth-assigned sex (four of six contrasts) and general behavioral and emotional problems (six of six contrasts) were the most consistent predictors of suicidality. With regard to birth-assigned sex, the higher rate of suicidality among birth-assigned females was evident on both the CBCL and YSR in all three clinics in the majority of comparisons and in all between-sex comparisons in the U.S. and Dutch referred and non-referred standardization data. This pattern is consistent with many other studies which have shown that suicidality is more common among birth-assigned female adolescents than it is among birth-assigned male adolescents [93].

The analyses showed quite clearly that the sum of general behavioral and emotional problems was strongly related to degree of suicidality. For the Toronto–Amsterdam contrasts, parent’s marital status and social class were also significant predictors for the CBCL suicidality metric, but not on the YSR. It is of interest to note that none of the six contrasts found evidence of a significant effect at p ≤ 0.05 for year of assessment with regard to degree of suicidality. In recent years, there has been a remarkable increase in the number of adolescents seeking out mental health services for GD [73, 75, 94] and a corresponding increase in the number of hospital-based clinics to care for these adolescents [95]. The increase in number of referrals might be related to the increasing acceptance/destigmatization of transgender adolescents in the culture at large, which could lead to the prediction that adolescents seen in more recent years would have lower suicidality scores. Yet, at least in our data set, we did not find any strong evidence that more recently assessed adolescents were any less suicidal than adolescents seen many years ago. This finding is entirely consistent with Liu et al.’s [96] meta-analysis regarding correlates of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) among predominantly community samples of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adolescents and adults. In their meta-analysis of studies published between 2005 and 2020, Liu et al. found that the rate of NSSI did not change over time and remained elevated compared to cisgender, heterosexual controls.

One strength of our study was its large sample size, which was higher than all of the prior studies listed in the Appendix combined. Although the Toronto and Amsterdam clinics contributed much smaller sample sizes than the London clinic, their respective numbers were still larger than 15 of the 16 clinic-based studies listed in the Appendix. A second strength was the use of a standardized metric of suicidality and our capacity to compare our data with the CBCL and YSR standardization samples. Although the suicidality metric might be deemed crude, at least one study has established its external validity [81]. One specific limitation of the CBCL/YSR suicidality metric is the ambiguous wording of Item 18 (“Deliberately harms self or attempts suicide”/ “I deliberately try to hurt or kill myself”): it, no doubt, captures non-suicidal self-injury, bona fide suicide attempts or both. Future studies would benefit from more sensitive, dimensional measures that use multiple items with a broader severity range, such as the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire-Jr. [97], the Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behavior Interview [98], the Columbia Suicide Screen [99] or the use of the proposed criteria for Suicidal Behavior Disorder and Nonsuicidal Self-Injury provided in the Conditions for Further Study section of the DSM-5 [100].

Conclusions

In general, our data would support the view that transgender adolescents should be routinely screened for the presence of suicidal ideation and behavior, much like referred adolescents at large. For transgender adolescents who experience suicidality, a clinical assessment can then attempt to formulate possible determinants, such as: (1) a response to the distress associated with GD; (2) a response to social experiences pertaining to within-family and/or peer-related rejection, consistent with the minority stress model as originally formulated by Meyer [65]; (3) an indicator or sign for the presence of other mental health problems (e.g., a mood disorder); and/or (4) a family history that might confer an underlying risk (e.g., a history of suicidality in first-degree relatives).

Although our data suggest that elevated rates of suicidality are a clinical issue requiring attention in some transgender adolescents, it should, of course, be noted that the majority of the adolescents, either by parent-report or self-report, did not report such thoughts or behaviors (as was also the case in the referred standardization samples). It is, therefore, important to understand the factors that contribute to individual differences in suicidality, just as it is required for understanding the substantial variation that transgender adolescents show with regard to psychopathology in general [101]. Along the same lines, it is also important to recognize that putative risk factors associated with suicidality show important variation among adolescents diagnosed with GD or who self-identify as transgender.

In the Perez-Brumer et al. [26] study, for example, the mean Victimization score for the transgender high school students was only 0.92 (absolute range, 0–9), suggesting that victimization experiences were not particularly frequent. In previous studies, it has been shown that poor peer relations (in the form of “bullying”) is elevated among adolescents with GD compared to non-clinical controls (e.g., [90]) or transgender high school students compared to cisgender high school students (e.g., [27]). Yet, in the present study, the poor peer relations metric was a significant predictor of suicidality in only one of the six contrasts in the multiple regression analyses, probably, because it was “wiped out” by the general behavior problem metric, a pattern that was also found in a community sample of gender-nonconforming children [102]. Similarly, in Perez-Brumer et al. [26], a more substantial predictor of suicidality was a positive response to a question pertaining to depression, which is quite consistent with our finding of a very strong association between behavioral and emotional problems in general and suicidality, and consistent with other studies [31, 53, 54, 103]. As shown elsewhere, on both the CBCL and the YSR, clinic-referred transgender adolescents have poorer peer relations than non-referred adolescents using the same metric that was employed in the present study [92, Table 4]. Nonetheless, this is not meant to minimize the importance in evaluating the quality of peer relationships among transgender adolescents and, as noted by MacMullin et al. [102] the CBCL/YSR metric of poor peer relations has its limitations, as it was developed as a form of secondary data analysis. Lastly, attention to protective factors for suicidality, such as within-family support or to intra-individual resilience parameters, would be important to examine [3, 30, 104,105,106]. Further research into these protective and predictive factors should be used to develop transgender-specific and adequate suicide prevention initiatives [107].

Notes

The total trans sample in Veale et al. [23] was 300, but 69–101 participants did not answer the questions about suicidality (J. F. Veale, personal communication, January 3, 2017).

This percentage was based only on participants who self-identified as transgender but not those who self-identified as genderqueer, gender fluid, etc.

The Toronto clinic was established in 1975 at the Clarke Institute of Psychiatry (now the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health). In the Toronto clinic, the CBCL was first administered as part of an assessment protocol in 1980 and the YSR in 1986 (the year it became available for use) [72]. The Amsterdam clinic was established in 1987 at the University Medical Center Utrecht in Utrecht. It moved to Amsterdam in 2002. In the Dutch clinic, the CBCL was used from 1990 on and the YSR was first administered as part of an assessment protocol in 1993. The London clinic was established in 1989 at St. George’s Hospital in London and moved to the Tavistock and Portman NHS Trust in 1996. When the London clinic became nationally funded in 2009, the CBCL and YSR became part of a routine data base (D. Di Ceglie, personal communication, June 2, 2020).

DSM-III, DSM-III-R, DSM-IV, DSM-IV-TR or DSM-5 were used, depending on the year of assessment. In DSM-III and III-R, the diagnostic term was Transsexualism, not Gender Identity Disorder, which was first used as the diagnostic term in the DSM-IV. In this article, we use the DSM-5 diagnostic label of Gender Dysphoria.

These correlations were calculated based on the raw CBCL/YSR standardization data which were provided by T. M. Achenbach for the U.S. samples and F. C. Verhulst for the Dutch samples

References

Dhejne C, Van Vlerken R, Heylens G, Arcelus J (2016) Mental health and gender dysphoria: a review of the literature. Int Rev Psychiatry 28:44–57

Nobili A, Glazebrook C, Arcelus J (2018) Quality of life of treatment-seeking transgender adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 19:199–220

Valentine SE, Shipherd JC (2018) A systematic review of social stress and mental health among transgender and gender non-conforming people in the United States. Clin Psychol Rev 66:24–38

Zucker KJ, Lawrence AA, Kreukels BPC (2016) Gender dysphoria in adults. Ann Rev Clin Psychol 12:217–247

Connolly MD, Zervos MJ, Barone CJ, Johnson CC, Joseph CLM (2016) The mental health of transgender youth: advances in understanding. J Adolesc Health 59:489–495

Russell ST, Fish JN (2016) Mental health in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth. Ann Rev Clin Psychol 12:465–487

Spivey LA, Edwards-Leeper L (2019) Future directions in affirmative psychological interventions with transgender children and adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 48:343–356

Zucker KJ, Bradley SJ (1995) Gender identity disorder and psychosexual problems in children and adolescents. Guilford Press, New York

Zucker KJ, Wood H, VanderLaan DP (2014) Models of psychopathology in children and adolescents with gender dysphoria. In: Kreukels BPC, Steensma TD, de Vries ALC (eds) Gender dysphoria and disorders of sex development: progress in care and knowledge. Springer, New York, pp 171–192

di Giacomo E, Krausz M, Colmegna F, Aspesi F, Clerici M (2018) Estimating the risk of attempted suicide among sexual minority youths: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr 172:1145–1152

Haas AP, Eliason M, Mays VM, Mathy RM, Cochran SD, D’Augelli AR, Clayton PJ (2011) Suicide and suicide risk in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations: review and recommendations. J Homosex 58:10–51

Liu RT, Walsh RFL, Sheehan AE, Cheek SM, Carter SM (2020) Suicidal ideation and behavior among sexual minority and heterosexual youth: 1995–2017. Pediatrics 145(3):e2019221

Marshall MP, Dietz LJ, Friedman MS, Stall R, Smith HA, McGinley J, Brent DA (2011) Suicidality and depression disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth: a meta-analytic review. J Adolesc Health 49:115–123

Porta CM, Watson RJ, Doull M, Eisenberg ME, Grumdahl N, Saewyc E (2018) Trend disparities in emotional distress and suicidality among sexual minority and heterosexual Minnesota adolescents from 1998 to 2010. J Sch Health 88:605–614

Boylan, J. F. (2015, January 6). How to save your life: A response to Leelah Alcorn’s suicide note. New York Times. from https://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/07/opinion/a-response-to-leelah-alcorns-suicide-note.html?_r=0. (Accessed 7 Nov 2015)

Clark KA, Blosnich JR, Haas AP, Cochran SD (2019) Estimate of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth suicide is inflated [Letter to the Editor]. J Adolesc Health 64:810

Haas AP, Lane AD, Blosnich JR, Butcher BA, Mortali MG (2019) Collecting sexual orientation and gender identity information at death. Am J Public Health 109:255–259

Lyons BH, Walters ML, Jack SPD, Petrosky E, Blair JM, Ivey-Stephenson AZ (2019) Suicides among lesbian and gay male individuals: findings from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Am J Prev Med 56:512–521

Ream GL (2019) What’s unique about lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth and young adult suicides? Findings from the National Violent Death Reporting System. J Adolesc Health 64:602–607

Gill-Peterson J (2018) Histories of the transgender child. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis

Clark KA, Cochran SD, Maiolatesi AJ, Pachankis JE (2020) Prevalence of bullying among youth classified as LGBTQ who died by suicide as reported in the National Violent Death Reporting System, 2003–2017. JAMA Pediatr. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0940

Grossman AH, D’Augelli AR (2007) Transgender youth and life-threatening behaviors. Suicide Life Threat Behav 37:527–537

Veale JF, Watson RJ, Peter T, Saewyc EM (2017) Mental health disparities among Canadian transgender youth. J Adolesc Health 60:44–49

Toomey RB, Syvertsen AK, Shramko M (2018) Transgender adolescent suicide behavior. Pediatrics 142(4):e20174218. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-4218

Thoma BC, Salk RH, Choukas-Bradley S, Goldstein TR, Levine MD, Marshal MP (2019) Suicidality disparities between transgender and cisgender adolescents. Pediatrics 144(5):e20191183

Perez-Brumer A, Day JK, Russell ST, Hatzenbuehler ML (2017) Prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation among transgender youth in California: Findings from a representative, population-based sample of high school students. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 56:739–746

Johns MM, Lowry R, Andrzejewski J, Barrios LC, Demissie Z, McManus T, Underwood MJ (2019) Transgender identity and experiences of violence victimization, substance use, suicide risk, and sexual risk behaviors among high school students–19 states and large urban school districts, 2017. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 68:67–71

Jackman KB, Caceres BA, Kreuze EJ, Bockting WO (2019) Suicidality among gender minority youth: Analysis of 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey data. Arch Suicide Res. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2019.1678539

Clark TC, Lucassen MFG, Bullen P, Denny SJ, Fleming TM, Robinson EM, Rossen FV (2014) The health and well-being of transgender high school students: results from the New Zealand Adolescent Health Survey (Youth’12). J Adolesc Health 55:93–99

Taliaferro LA, McMorris BJ, Eisenberg ME (2018) Connections that moderate risk of non-suicidal self-injury among transgender and gender non-conforming youth. Psychiatry Res 268:65–67

Taliaferro LA, McMorris BJ, Rider GN, Eisenberg ME (2019) Risk and protective factors for self-harm in a population-based sample of transgender youth. Arch Suicide Res 23:203–221

Di Ceglie, D., Freedman, D., McPherson, S., Richardson, P. (2002). Children and adolescents referred to a specialist gender identity development service: Clinical features and demographic characteristics. Int J Transgend 6(1). Retrieved from https://www.symposion.com/ijt/ijtvo06no01_01.htm

Skagerberg E, Parkinson R, Carmichael P (2013) Self-harming thoughts and behaviors in a group of children and adolescents with gender dysphoria. Int J Transgend 14:86–92

Becker M, Gjergji-Lama V, Romer G, Möller B (2014) Merkmale von Kindern und Jugendlichen mit Geschlechtsdysphorie in der Hamburger Spezialsprechstunde [Characteristics of children and adolescents with gender dysphoria referred to the Hamburg Gender Identity Clinic]. Prax Kinderpsychiatr Kinderpsyc 63:486–509

Khatchadourian K, Amed S, Metzger DL (2014) Clinical management of youth with gender dysphoria in Vancouver. J Pediatr 164:906–911

Chapman MR, Hughes J, Sherrod JL, Lopez X, Jenkins B, Emslie G (2015) Psychiatric symptoms and suicidality in a sample of gender dysphoric youth presenting to a newly established multidisciplinary program, GENder Education and Care Interdisciplinary Support (GENECIS), within a pediatric medical setting. Poster presented at the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, San Antonio TX

Kaltiala-Heino R, Sumia M, Työläjärvi M, Lindberg N (2015) Two years of gender identity service for minors: overrepresentation of natal girls with severe problems in adolescent development. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 9:9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-015-0042-y

Olson J, Schrager SM, Belzer M, Simons LK, Clark LF (2015) Baseline physiologic and psychosocial characteristics of transgender youth seeking care for gender dysphoria. J Adolesc Health 57:374–380

Holt V, Skagerberg E, Dunsford M (2016) Young people with features of gender dysphoria: demographics and associated difficulties. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 21:108–118

Peterson CM, Matthews A, Copps-Smith E, Conrad LA (2017) Suicidality, self-harm, and body dissatisfaction in transgender adolescents and emerging adults with gender dysphoria. Suicide Life Threat Behav 47:475–482

Fisher AD, Ristori J, Castellini G, Sensi C, Cassiolo E, Prunas A, Maggi M (2017) Psychological characteristics of Italian gender dysphoric adolescents: a case-control study. J Endocrinol Invest 40:953–965

Nahata L, Quinn GP, Caltabellotta NM, Tishelman AC (2017) Mental health concerns and insurance denials among transgender adolescents. LGBT Health 4:188–193

Becerra-Culqui TA, Liu Y, Nash R, Cromwell L, Flanders D, Getahun D, Goodman M (2018) Mental health of transgender and gender nonconforming youth compared with their peers. Pediatrics 141(5):e20173845

Brocksmith VM, Alradadi RS, Chen M, Eugster EA (2018) Baseline characteristics of gender dysphoric youth. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 31:1367–1369

Chen M, Fuqua J, Eugster EA (2016) Characteristics of referrals for gender dysphoria over a 13-year period. J Adolesc Health 58:369–371

Allen LR, Watson LB, Egan AM, Moser CN (2019) Well-being and suicidality among transgender youth after gender-affirming hormones. Clin Pract Paediatr Psychol 7:302–311

Moyer DN, Connelly KJ, Holley AL (2019) Using the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 to screen for acute distress in transgender youth: Findings from a pediatric endocrinology clinic. J Paediatr Endocrinol Metab 28:71–74

Sorbara J (2019) Does age matter? Mental health implications and determinants of when youth present toa gender clinic. Unpublished Master’s thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto

Chiniara LN, Bonifacio HJ, Palmert MR (2018) Characteristics of adolescents referred to a gender clinic: are youth seen now different from those in initial reports? Horm Res Paediatr 89:434–441

Bettis AH, Thompson EC, Burke TA, Nesi J, Kudinova AY, Hunt JI, Wolff JC (2020) Prevalence and clinical indices of risk for sexual and gender minority youth in an adolescent inpatient sample. J Psychiatr Res 130:327–332

Achille C, Taggart T, Eaton NR, Osipoff J, Tafuri K, Lane A, Wilson TA (2020) Longitudinal impact of gender-affirming endocrine intervention on the mental heatlh and well-being of transgender youths: preliminary results. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13633-020-00078-2

Heard J, Morris A, Kirouac N, Ducharme J, Trepel S, Wicklow B (2018) Gender dysphoria assessment and action for youth: review of health care services and experiences of trans youth in Manitoba. Pediat Child Health 23:179–184

Spack NP, Edwards-Leeper L, Feldman HA, Leibowitz S, Mandel F, Diamond DA, Vance SR (2012) Children and adolescents with gender identity disorder referred to a pediatric medical center. Pediatrics 129:418–425

Peterson CM, Mara CA, Conard LAE, Grossoehme D (2020) The relationship of the UPPS model of impulsivity and bulimic symptoms and non-suicidal self-injury in transgender youth. Eat Behav. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2020.101416

Berona J, Horwitz AG, Czyz EK, King CA (2020) Predicting suicidal behavior among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth receiving psychiatric emergency services. J Psychiatr Res 122:64–69

Mak J, Shires DA, Zhang Q, Prieto LR, Ahmedani BK, Kattari L, Goodman M (2020) Suicide attempts among a cohort of transgender and gender diverse people. Am J Prev Med 59:570–577

Arcelus J, Claes L, Witcomb L, Marshall E, Bouman WP (2016) Risk factors for non-suicidal self-injury among trans youth. J Sex Med 13:402–412

Kuper LE, Adams N, Mustanski BS (2018) Exploring cross-sectional predictors of suicidal ideation, attempt, and risk in a large online sample of transgender and gender nonconforming youth and young adults. LGBT Health 5:391–400

Reisner SL, Vetters R, Leclerc M, Zaslow S, Wolfrum S, Shumer D, Mimiaga MJ (2015) Mental health of transgender youth in care at an adolescent urban community health center: a matched retrospective cohort study. J Adolesc Health 56:274–279

Thorne N, Witcomb GL, Nieder T, Nixon E, Yip A, Arcelus J (2019) A comparison of mental health symptomatology and levels of social support in young treatment seeking transgender individuals who identify as binary and non-binary. Int J Transgend 20:241–250

Surace T, Fusar-Poli L, Vozza L, Cavone V, Arcidiacono C, Mammano R, Aguglia E (2020) Lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation and behaviors in gender non-conforming youths: a meta-analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01508-5

Mann EE, Taylor A, Wren B, de Graaf N (2019) Review of the literature on self-injurious thoughts and behaviours in gender-diverse children and young people in the United Kingdom. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 24:304–321

McNeil J, Ellis SJ, Eccles FJR (2017) Suicide in trans populations: a systematic review of prevalence and correlates. Psychol Sex Orient Gender Divers 4:341–353

Hendricks ML, Testa RJ (2012) A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: an adaptation of the minority stress model. Psychol Res Practice 43:460–467

Meyer IH (2003) Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull 129:674–697

Spivey LA, Prinstein MJ (2019) A preliminary examination of the association between adolescent gender nonconformity and suicidal thoughts and behaviors. J Abnorm Child Psychol 47:707–716

Brent DA, Oquendo M, Birmaher B, Greenhill L, Kolko D, Stanley B, Mann JJ (2002) Familial pathways to early-onset suicide attempt: risk for suicidal behavior in offspring of mood-disordered suicide attempters. Arch Gen Psychiatry 59:801–807

Fu Q, Heath AC, Bucholz KK, Nelson EC, Glowinski AL, Goldberg J, Eisen SA (2002) A twin study of genetic and environmental influences on suicidality in men. Psychol Med 32:11–24

Statham DJ, Heath AC, Madden PA, Bucholz KK, Bierut L, Dinwiddie SH, Martin NG (1998) Suicidal behaviour: an epidemiological and genetic study. Psychol Med 28:839–855

Garber J, Hollon SD (1991) What can specificity designs say about causality in psychopathology research? Psychol Bull 110:129–136

Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA (1996) Equifinality and multifinality in developmental psychopathology [Editorial]. Dev Psychopathol 8:597–600

Achenbach TM, Edelbrock C (1987) Manual for the Youth Self-Report and Profile. University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry, Burlington, VT

de Graaf NM, Giovanardi G, Zitz C, Carmichael P (2018) Sex ratio in children and adolescents referred to the Gender Identity Development Services in the UK (2009–2016) [Letter to the Editor]. Arch Sex Behav 47:1301–1304

Handler T, Hojilla JC, Varghese R, Wellenstein W, Satre DD, Zaritsky E (2019) Trends in referrals to a pediatric transgender clinic. Pediatrics 144(5):e20191368

Kaltiala R, Bergman H, Carmichael P, de Graaf NM, Egebjerg Rischel K, Frisén L, Wahre A (2020) Time trends in referrals to child and adolescent gender identity services: a study in four Nordic countries and in the UK. Nord J Psychiatry 74:40–44

Cohen-Kettenis PT, Owen A, Kaijser VG, Bradley SJ, Zucker KJ (2003) Demographic characteristics, social competence, and behavior problems in children with gender identity disorder: a cross-national, cross-clinic comparative analysis. J Abnorm Child Psychol 31:41–53

Hollingshead AB (1975) Four factor index of social status. Department of Sociology, Yale University, New Haven, CT

Achenbach TM (1991) Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 and 1991 Profile. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry, Burlington, VT

Verhulst FC, van der Ende J, Koot HM (1996) Handleiding voor de CBCL/4-18 [Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and Revised Child Behavior Profile]. Department of Child and Adolescents Psychiatry, Erasmus University, Rotterdam

Verhulst FC, van der Ende J, Koot HM (1997) Handleiding voor de Youth Self Report [Manual for the Youth Self Report]. Department of Child and Adolescents Psychiatry, Erasmus University, Rotterdam

Van Meter AR, Perez Algorta G, Youngstrom EA, Lechtman Y, Youngstrom JK, Feeny NC, Findling RL (2018) Assessing for suicidal behavior in youth using the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 27:159–169

Zucker KJ, Bradley SJ, Sanikhani M (1997) Sex differences in referral rates of children with gender identity disorder: some hypotheses. J Abnorm Child Psychol 25:217–227

Cohen-Kettenis PT, Steensma TD, de Vries ALC (2011) Treatment of adolescents with gender dysphoria in the Netherlands. Child Adolesc Psychiatric Clin N Am 20:689–700

Zucker KJ, Bradley SJ, Owen-Anderson A, Singh D, Blanchard R, Bain J (2011) Puberty-blocking hormonal therapy for adolescents with gender identity disorder: a descriptive clinical study. J Gay Lesbian Mental Health 15:58–82

Costa R, Dunsford M, Skagerberg E, Holt V, Carmichael P, Colizzi M (2015) Psychological support, puberty suppression, and psychosocial functioning in adolescents with gender dysphoria. J Sex Med 12:2206–2214

Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA (2001) Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, Families, Burlington, VT

Tick NT, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC (2007) Twenty-year trends in emotional and behavioral problems in Dutch children in a changing society. Acta Psychiatr Scand 116:473–548

Tick NT, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC (2008) Ten-year trends in self-reported emotional and behavioral problems in Dutch adolescents. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 43:349–355

de Vries ALC, Steensma TD, Cohen-Kettenis PT, VanderLaan DP, Zucker KJ (2016) Poor peer relations predict parent- and self-reported behavioral and emotional problems of adolescents with gender dysphoria: a cross-national, cross-clinic comparative analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 25:579–588

Shiffman M, VanderLaan DP, Wood H, Hughes SK, Owen-Anderson A, Lumley MM, Zucker KJ (2016) Behavioral and emotional problems as a function of peer relationships in adolescents with gender dysphoria: a comparison to clinical and non-clinical controls. Psychol Sex Orient Gender Divers 3:27–36

Steensma TD, Zucker KJ, Kreukels BPC, VanderLaan DP, Wood H, Fuentes A, Cohen-Kettenis PT (2014) Behavioral and emotional problems on the Teacher’s Report Form: a cross-national, cross-clinic comparative analysis of gender dysphoric children and adolescents. J Abnorm Child Psychol 42:635–647

Zucker KJ, Bradley SJ, Owen-Anderson A, Kibblewhite SJ, Wood H, Singh D, Choi K (2012) Demographics, behavior problems, and psychosexual characteristics of adolescents with gender identity disorder or transvestic fetishism. J Sex Marital Ther 38:151–189

Miranda-Mendizabal A, Castellví P, Parés-Badell O, Alayo I, Almenara J, Alonso I, Alonso J (2019) Gender differences in suicidal behavior in adolescents and young adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Int J Public Health 64:265–283

Aitken M, Steensma TD, Blanchard R, VanderLaan DP, Wood H, Fuentes A, Spegg C, Wasserman L, Ames M, Fitzsimmons CL, Leef JH, Lishak V, Reim E, Takagi A, Vinik J, Wreford J, Cohen-Kettenis PT, de Vries ALC, Kreukels BPC, Zucker KJ (2015) Evidence for an altered sex ratio in clinic-referred adolescents with gender dysphoria. J Sex Med 12:756–763

Hsieh S, Leininger J (2014) Resource list: clinical care programs for gender-nonconforming children and adolescents. Pediatr Ann 43:238–244

Liu RT, Sheehan AE, Walsh RFL, Sanzari CM, Cheek SM, Hernandez EM (2019) Prevalence and correlates of non-suicidal self-injury among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2019.101783

Reynolds WM, Mazza JJ (1999) Assessment of suicidal ideation in inner-city children and young adolescents: reliability and validity of the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire-Jr. School Psychol Rev 28:17–30

Nock MK, Holmberg EB, Photos VI, Michel BD (2007) The Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview: development, reliability, and validity in an adolescent sample. Psychol Assess 19:309–317

Shaffer D, Scott M, Wilcox H, Maslow C, Hicks R, Lucas CP, Greenwald S (2004) The Columbia suicide screen: validity and reliability of a screen for youth suicide and depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 43:71–79

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edn. American Psychiatric Press, Arlington, VA

Savin-Williams RC, Ream GL (2003) Suicide attempts among sexual-minority male youth. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 32:509–522

MacMullin LN, Aitken M, Nabbijohn AN, VanderLaan DP (2020) Self-harm and suicidality in gender-nonconforming children: a Canadian community-based parent-report study. Psychol Sex Orient Gender Divers 7:76–90

Walls NE, Atteberry-Ash B, Kattari SK, Peitzmeier S, Kattari L, Langenderfer-Magruder L (2019) Gender identity, sexual orientation, mental health, and bullying as predictors of partner violence in a representative sample of youth. J Adolesc Health 64:86–92

Hunt QA, Morrow QJ, McGuire JK (2020) Experiences of suicide in transgender youth: a qualitative, community-based study. Arch Suicide Res 24(sup2):S340–S355

McNanama O’Brien KH, Putney JM, Hebert NW (2016) Sexual and gender minority youth suicide: understanding subgroup differences to inform interventions. LGBT Health 3:248–251

Moody C, Smith NG (2013) Suicide protective factors among trans adults. Arch Sex Behav 42:739–752

dickey M, Budge SL (2020) Suicide and the transgender experience. Am Psychol 75:380–390

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Use of the data from the CAMH site received ethics approval (CAMH Research Ethics Board, Protocol No. 228–2012 and 089–2013), but ethics approval from the Amsterdam and London clinics was not required because the CBCL and YSR were deemed as routine outcome measures. Therefore, this study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Appendix

Appendix

Clinic-Based Studies of Suicidality in Transgender Adolescents.

Study/year of Publication | N | Metric | Source | Time frame |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Di Ceglie et al. [32] | 69 | Self-harm: 23% | Chart review | Lifetime |

Self-injurious behavior: 22% | ||||

Skagerberg et al. [33]a | 97 | Suicidal ideation: 17.1% | Chart review | Lifetime |

Self-harm: 32.3% | YSR | |||

Suicide attempts: 16.1% | ||||

Becker et al. [34] | 40 | Suicidal ideation: 42.2% | Chart review | Current |

Self-harm: 26.5% | Current | |||

Suicide attempts: 11.8% | Current | |||

Combined: 51.5% | Lifetime | |||

Khatchadourian et al. [35] | 84 | Suicide attempts: 12% | Chart review | Lifetime |

Chapman et al. [36] | 43 | Suicidal ideation: 51.2% | Self-report | Lifetime |

Self-harm: 41.9% | ||||

Suicide attempts: 16.3% | ||||

Kaltiali et al. [37] | 47 | Suicidal ideation and self-harm (combined): 53% | Chart review | Unclear |

Olson et al. [38] | 49 | Suicidal ideation: 51% | Self-report | Lifetime |

Suicide attempts: 30% | Lifetime | |||

Holt et al. [39] | 177 | Suicidal ideation: 39.5% | Chart review | Lifetime |

Self-harm: 44.1% | ||||

Suicide attempts: 15.8% | ||||

Peterson et al. [40] | 89 | Self-harm: 41.8% | Chart review | Lifetime |

Suicide attempts: 30.3% | ||||

Fisher et al. [41] | 46 | Multi-Attitude Suicide Tendency Scale | Self-report | |

Suicidal ideation: 86.9% | Unclear | |||

Suicide attempts: 13.0% | Unclear | |||

Nahata et al. [42] | 79 | Suicidal ideation: 74.7% | Chart review | Lifetime |

Self-harm: 55.7% | ||||

Suicide attempts: 30.4% | ||||

Becerra-Culqui et al.[43]b | 1082 | Suicidal ideation: 6.2% | Chart review | Prior 6 months |

Suicidal ideation: 9.2% | (ICD-9 code) | Lifetime | ||

Self-harm: 3.2% | Prior 6 months | |||

Self-harm: 6.0% | Lifetime | |||

Brocksmith et al. [44] (see also Chen et al. [45]) | 78 | “Suicidality”: 10.2% | Chart review | Unclear |

Allen et al. [46] | 47 | Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (n = 4)c | Self-report | “past few weeks” |

Moyer et al. [47] | 79 | Suicidal ideation: 35.9% | Patient Health Questionnaire for depression (PHQ-9) | Past 2 weeks |

Sorbara [48] (see also Chiniara et al. [49]) | 300 | Suicidal ideation: 47.3% | Chart review | Lifetime |

“Active” suicidal ideation: 12.3% | Current | |||

Self-harm: 34.6% | Lifetime | |||

Suicide attempts: 14.0% | Lifetime | |||

Bettis et al. [50] | 31 | Suicidal ideationd | Self-injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Inventory | Past month |

Non-suicidal self-injury: 70.1% | Questionnaire-Jr | Past 12-month frequency | ||

Suicidal Ideation | Lifetime | |||

Suicide attempt: 54.83% | Self-report | Lifetime | ||

With the exception of Becerra-Culqui et al. [43]), Becker et al. [34], and Nahata et al. [42]), the table does not include mixed samples of children and adolescents [51,52,53,54,55,56] or of adolescents and young adults [57,58,59,60,61,62,63]. Inclusion of children would likely result in lower percentages for suicidal behavior. Surace et al. [61] reported a meta-analysis of lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation and behavior in samples of “gender non-conforming” children, adolescents, and adults. Regarding adolescents, their meta-analysis, for reasons that are unclear, did not capture at least 11 of the clinic-based studies [32, 34,35,38, 40, 41, 44, 46,47,48] that we report on in this Appendix. For prior reviews, see [62, 63].

aPercentages extracted from Table 3.

bData from two healthcare systems in the United States, but the clients were not necessarily seen in a specialized gender identity clinic.

cPercentages per item not reported.

dDimensional multi-item measure (frequency/severity); percentage data not reported.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

de Graaf, N.M., Steensma, T.D., Carmichael, P. et al. Suicidality in clinic-referred transgender adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 31, 67–83 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01663-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01663-9