Abstract

Almost 80 million people globally are forcibly displaced. A small number reach wealthy western countries and seek asylum. Over half are children. Wealthy reception countries have increasingly adopted restrictive reception practices including immigration detention. There is an expanding literature on the mental health impacts of immigration detention for adults, but less about children. This scoping review identified 22 studies of children detained by 6 countries (Australia, Canada, Hong Kong, Netherlands, the UK and the US) through searches of Medline, PsychINFO, Emcare, CINAHL and Scopus data bases for the period January 1992–May 2019. The results are presented thematically. There is quantitative data about the mental health of children and parents who are detained and qualitative evidence includes the words and drawings of detained children. The papers are predominantly small cross-sectional studies using mixed methodologies with convenience samples. Despite weaknesses in individual studies the review provides a rich and consistent picture of the experience and impact of immigration detention on children’s wellbeing, parental mental health and parenting. Displaced children are exposed to peri-migration trauma and loss compounded by further adversity while held detained. There are high rates of distress, mental disorder, physical health and developmental problems in children aged from infancy to adolescence which persist after resettlement. Restrictive detention is a particularly adverse reception experience and children and parents should not be detained or separated for immigration purposes. The findings have implications for policy and practice. Clinicians and researchers have a role in advocacy for reception polices that support the wellbeing of accompanied and unaccompanied children who seek asylum.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates that in late 2019, 79.5 million people were involuntarily displaced and ‘of concern’ as a consequence of war, persecution and environmental factors, and 26 million were refugees [1]. Over half are children. The vast majority (85%) are displaced internally or to neighbouring countries. During the last decade millions of people have travelled to countries in Europe, north America and to Australia seeking asylum, primarily as a consequence of protracted violence in Syria, other countries in the middle east, in northern Africa, and in central and south America [2].

As the number of people seeking asylum has increased, reception countries in Europe and North America have increasingly adopted restrictive immigration policies, including immigration detention for people arriving without documentation and seeking asylum. Australia has had a policy of mandatory indefinite detention of all adults and children arriving undocumented by boat since 1992. Immigration detention is associated with human rights violations, safety concerns and deteriorating mental health, including for accompanied and unaccompanied children [3,4,5,6,7,8,9].

There is an established literature confirming exposure of children to cumulative risks at each stage of what is called the ‘refugee journey’: forced displacement, flight and resettlement. The literature includes systematic reviews on the mental health and/or wellbeing of child and adolescent refugees, accompanied and unaccompanied [10, 11], when resettled in high, low and middle-income countries [12,13,14], or living in refugee camps [15]. These studies identify the diversity of this population, in their demographics, experiences and circumstances. There is consensus that exposure to violence at any stage of the ‘journey’, separation from or loss of a parent, and lack of support in resettlement all increase vulnerability to mental health problems [12, 13].

Unaccompanied children have higher rates of mental distress and illness than children displaced with their parents [16, 17]. However, a growing number of studies with refugee families demonstrate that parental mental illness including Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) increase the risk of harsh parenting and child maltreatment during displacement and in resettlement [18,19,20,21].

Research with people held in closed immigration detention is difficult, with many practical and ethical challenges arising in this highly restrictive, often politicised environment [22,23,24]. When access is possible, the diversity and high levels of distress and administrative if not personal vulnerability of the population raise questions about informed consent [25]. There are additional challenges in all research with children, particularly when they are unaccompanied [26,27,28,29].

The adverse impact of immigration detention in the generation and aggravation of mental illness has been confirmed for adults held in immigration detention with systematic reviews identifying high rates of comorbid mental disorder, particularly PTSD and MDD, elevated rates of self-harm and persisting difficulties after release [30,31,32,33]. Most studies with adults show an association between duration of detention and poor mental health, although a deterioration after even short periods of restrictive detention has been identified [34].

There are no systematic or scoping review papers specifically on the consequences of detaining children and families who seek asylum. This review aimed to identify the extent of the qualitative and quantitative evidence about the mental health consequences of immigration detention for child refugees and asylum seekers detained by Western countries.

Methodology

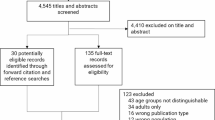

A scoping review of the international peer reviewed literature in English was undertaken to answer the question: ‘What is the current evidence in the peer reviewed literature, about the impact of immigration detention on children and families who seek asylum?’ Scoping methodology was used to provide an overview of the topic, reviewing the small and diverse body of literature and identifying gaps in the evidence [35,36,37]. A PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews was recently published [38]. The Scoping review process is summarised in Fig. 1. The relatively small number of studies using a range of methodological approaches precluded the meta-analytic approach required for a systematic review.

Relevant studies were identified through a search of the Medline, PsychINFO, Emcare, CINAHL and Scopus data bases from January 1992 to May 2019. Search terms included; mental health/illness; refugees or asylum seekers; infant, child or adolescent; child development; family, parenting or child parent relationship.

Papers were included if they reported quantitative or qualitative data in English that:

-

1.

Included detained populations of children, adolescents and/or families who were refugees or seeking asylum; or were follow-up studies of previously detained populations; or were file audits, where post-migration adversity specifically included detention.

-

2.

Included mental health and/or developmental outcomes or information about children and adolescents.

-

3.

Were peer reviewed or had historical significance.

The terminology used to describe detention facilities varies. For example, the term ‘camp’ is used to describe open refugee settlements, more restrictive internment camps and imprisonment in penal facilities. Studies were only included when the environment in which children and parents were held was identifiably restrictive, authoritarian and institutionalised, resulting in extreme limitations of movement, autonomy and activity.

Results

Study selection

An iterative process enabled 5303 papers identified initially to be reduced to 127 papers. A further nine studies were identified while reviewing other papers. These 136 papers underwent full text review leaving 22 for inclusion.

The 114 relevant but ‘out of scope’ papers provide a comprehensive overview of publications in English between 1992 and mid 2019 about the mental health of displaced, refugee and asylum-seeking children and parents seeking asylum or resettled in third countries. These included systematic review, review and commentary papers on the mental health of refugee children and families who were not detained, commentary and review papers on immigration detention of children, studies on post-migration stressors other than immigration detention, and papers on interventions with refugee children and families.

This is a rapidly expanding field of inquiry. The number of data, review and commentary papers on the mental health vulnerabilities and needs of this population has risen significantly in recent years, and coincides with increasing numbers of people displaced, the large influx of refugees into Europe [3, 14] and more recently the crisis on the border of the United States and Mexico [39,40,41]. Half of the systematic review papers on the mental health of refugee children (7 out of 14), almost a third of the review or commentary papers (5 of 16), and more than half (19 of 34) papers on post-migration stressors were published in 2018–2019, that is the last 18 months of a 27-years review period.

Most studies acknowledge or consider to varying degrees the challenges of researching and addressing the mental health needs of displaced populations, and specifically children. Several authors identify alternative reception policies to immigration detention [6, 42, 43]. Considered together these papers highlight the cumulative nature of exposure to adversity prior to arrival in reception countries and, most relevant to this study, the influence of the post-migration environment in supporting or further exacerbating mental health difficulties for children and families.

Findings

Overview of the studies

The review identified 22 papers of varying significance published between 1992 and May 2019 that provide original data about the mental health of children and parents who were or had previously been held in restrictive immigration detention. There is diversity in methods and the pre and peri-migration experiences of the children and families, and in study methodologies. These are predominantly small cross-sectional samples, data audits or secondary data analyses using a mix of quantitative and qualitative methodologies and reporting data from various self and parent report measures.

The 22 papers are listed and summarized in Table 1 by country of reception. Nineteen studies report qualitative and/or a quantitative data based on direct observations of the detention environment, clinical assessments, and/or data from parent and child or adolescent self-report measures. Of these, seven include quantitative data from self-report measures collected, while children and parents were detained [44,45,46,47,48,49,50], and two report quantitative data collected post detention [51, 52]. Qualitative clinical and observational data is reported from visits to detention centres in six papers [53,54,55,56,57,58], and from a detained child in a single case report [59]. The sample in two quantitative Canadian studies includes observations and data from children collected during and post detention [60, 61]. Two papers, [50, 62] (one already mentioned) are comparison studies between children or young people held in restrictive detention compared with a more open setting or community resettlement. Two papers present clinical file audit data [63, 64] and one analyses data from children’s drawings that is in the public domain [65].

The findings are considered in relation to reception country, study context and population sample; evidence about the detention environment and the experience of detention; findings about mental health, including quantitative and qualitative data; and additional themes and issues.

Study contexts and population samples

There are considerable differences between and within reception countries and over time, in the legislative and geographical contexts within which restrictive immigration detention of children and families has been and is implemented [43, 66], including who is detained, when and for how long. The national, ethnic and religious background of people seeking asylum in third countries also changes in response to fluctuations in areas of significant global conflict, persecution and insecurity.

The 22 studies report on children and families with different language and cultural backgrounds who were detained by 6 wealthy reception countries. Variations in sample size and methodology are detailed in Table 1 and range from a study of over 600 children [56] to a single case report [59]. The study samples and methodologies are briefly summarized, grouped by national context.

Hong Kong

The largest and earliest study identified was conducted in collaboration with the UNHCR and International Catholic Child Bureau between April and June 1992. It reports on the circumstances and wellbeing of Vietnamese children detained in Hong Kong, aged ‘under 12’ to ‘16 and older’, 20% of whom were unaccompanied [56]. An estimated 18,000 Vietnamese children were then detained by Hong Kong. The report describes the adults and children as ‘warehoused in prison-like facilities which provide for control of the population’ [56]. A self-report survey about current living conditions and past trauma was completed by Vietnamese speaking staff with 603 children, and 56 children aged 9–18 years undertook in-depth clinical interviews with visiting north American child psychiatrists. The children had been detained between 9 and 42 months. This early study is significant, because it presents a comprehensive account of the environment and consequences of immigration detention for a large sample of asylum-seeking children, and anticipates issues that recur through studies published subsequently.

Australia

Thirteen papers of variable significance (more than half the 22 identified papers) report qualitative and quantitative data about immigration detention of children by Australia. A preponderance of papers from Australia was also found in a recent systematic review and metanalysis on the mental health of people held in immigration detention [33]. Australia has implemented mandatory detention of everyone arriving unauthorised by boat for 28 years. Mode of arrival influences how asylum seekers are treated during and following reception; asylum seekers who arrive by air are less often detained. Since 2013 additional deterrent policies mean that adult and child ‘unauthorised maritime arrivals’ have regularly been held for years in offshore and third country locations and denied permanent protection in Australia, even when identified as refugees [67]. This is now politically justified in terms of deterrence, preventing deaths at sea and border protection [68]. There are longstanding health and human rights concerns about Australia’s policies [9, 69,70,71,72]

In 2001 a participant–observer account from an Iraqi doctor detained by Australia, co-authored with a psychologist employed within the Immigration Detention Centre (IDC) [57] includes observations about the experience of detained children and the impact of detention on children and parenting. The following year the first paper specifically about immigration detention of children by Australia was published [53]. Qualitative observations, case vignettes and children’s drawings illustrate the setting and the experience and distress of detained parents and children. In 2003 Australian doctors at a major children’s hospital published the case report of a 6-year-old detained with his parents for months pending the outcome of their refugee application [59]. The boy had become mute and profoundly withdrawn, requiring repeated lifesaving hospitalisations for rehydration and refeeding. The paper presents his case in detail, includes two of his drawings and highlights the clinical and ethical dilemmas for involved clinicians.

In 2004 two Australian studies used different methodologies to document the mental health of adults and children in two groups of 10 families held in different remote IDCs. The simultaneous publication was deliberate, balancing the strengths and weaknesses of each methodological approach. One paper [47] used structured psychiatric interviews and various self-report measures including the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-age children (K-SADS-PL) [73] and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders (SCID-IV) [74]. These were administered over the phone by same-language speaking psychologists to assess lifetime and current psychiatric disorders in a population sample of ten families (14 adults and 20 children aged 3–19 years). The second paper [46] presents a consecutive clinical case series of ten families (16 adults and 20 children aged 11 months to 17 years) held in another remote IDC. This cohort were comprehensively assessed and treated by a multidisciplinary Child and Adolescent Mental Health (CAMH) team and consensus diagnoses were agreed. The findings include detail about the detention environment, qualitative and quantitative mental health data and identify obstacles to providing adequate mental health care in the detention environment.

In 2015 two qualitative papers were published simultaneously by medical consultants to the 2014 Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) Inquiry into Detention of Children [9]. These report observations and data collected during extended contact with families and children (230 individuals), predominantly from Afghanistan, Somalia, Sri Lanka, Syria, Iran and stateless Rohingya who were held in various IDC on remote Christmas Island [54, 55]. The first includes clinical vignettes and the parents’ words to illustrate the high levels of distress in detained families and children. The children’s experiences of institutional life, of exposure to violence and self-harm and their hopes and fears are included through their words and drawings. The second paper is based on interviews with 40 unaccompanied boys (UAM) aged 14–17 years, and three unaccompanied girls aged 17, held on Christmas Island for 6–8 months [55]. The paper includes direct quotes from the young people and a poem.

In 2016 a secondary analysis of mental health data collected from children and families detained on Christmas Island during the 2014 AHRC Inquiry (above) was published. The data had not previously been analyzed or reported [48]. The study includes quantitative Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) [75] data from 70 children aged 3–17 years, and results from 166 Kessler 10 Scales (K10) from adults and adolescents [76]. Gender and country of origin data was redacted. The children had been detained for a mean of 221 days (7.26 months). This paper also includes parental concerns about infants and children aged under 4 years old.

In 2018 the SDQ data from 48 children aged 4–15 years ( mean age 8.4 years) included in the previous Christmas Island study [48] was matched with the SDQ data from a comparable sample of 38 refugee children, never detained and resettled for a mean of 325 days (10.68 months) in Australia under the UNHCR resettlement program [62]. The community children are part of a longitudinal study of resettled refugee families [77]. While both sample populations are small and the data is limited to SDQ scores, this is a rare comparison of the mental health of separate cohorts who can be presumed to have similar premigration risk factors but very different reception experiences.

Four other Australian papers are included in the review findings. One analyses drawings by detained children sourced from secondary public sources [65]. Another reports observations from places designated as ‘Alternative Places of Detention’ (APOD), where children and families faced many restrictions similar to those in other detention facilities [58]. Two studies report retrospective analysis of medical records, the first being presentations of detained adults and children to the local Emergency Department(ED) in Darwin, northern Australia in 2011 [63]. The authors estimate that 50% of people then detained attended the ED at least once that year and children under 18 years made up 21.6% (n = 112) of presentations. Psychiatric presentations for adults and children are identified. The second study reports data from the health records of paediatric patients assessed by the West Australian Refugee Health Service between 2012 and 2016 [64]. The 110 children had a mean age of 6 years (SD 4.72 years) and 97.2% had been in immigration detention, on average for 7 months. Ninety percent were from Iran, Iraq, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan or were stateless Rohingya. Demographics, the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) [78] and the Refugee Adverse Experiences scale (R-ACE) [79] were documented in addition to health status.

United States of America (US)

Three studies of children detained by the US have been published, two in 1992 and the most recent in 2019. In 2002, Rothe and colleagues present qualitative and quantitative data about adolescents and parents who left Cuba by boat in 1994 and were detained at Guantanamo Bay for 6–8 months before resettlement in the US. The first paper [49] reports data from a ‘convenience clinical sample’ of 74 adolescents, (47 males, mean age 16 and 27 females mean age 15) who attended a volunteer health service in the camp. This was an estimated 9% of the 13–19 years then detained. Data was collected and analyzed from clinical interviews, self-report Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Reactive Index (PTSD-RI) [80], a checklist of eight symptoms indicating psychological distress, information about traumatic exposures including parental loss, the boat journey and camp experiences and drawings about “the first thing that comes to mind”. The authors describe the camp environment, children’s exposure to riots, violence and self-harm and the impact on the involved staff [49].

The second study considers a separate cohort of 87 Cuban children and adolescents aged 6–17 years, (average age of 14.9 years) 6 months after their resettlement in the US [52]. These children had not previously been identified as symptomatic and data was collected at school. Self-reported symptoms on the PTSD-RI and assessments of internalizing and externalizing behaviours using the Child Behaviour Checklist Teacher Report Form (CBCL-TRF) were collected [81].

The most recent paper included in the review [45] is the only study undertaken in the US itself, despite immigration detention of children being widely implemented [82]. The study used the SDQ with mothers of 425 children aged 4–17 years. A hundred and fifty children aged 9–17 years also completed the PTSD-RI. Children had been detained between 1 and 44 days (average 9 days). The paper reports very little about the environment in which mothers and children, primarily from Honduras, El Salvador or Guatemala, were detained. Seventeen percent of children had had a period of separation from their mother, all were separated from their fathers. None were currently unaccompanied. Forced family separation is discussed further below.

Netherlands

A single study from the Netherlands compares the mental health of 69 unaccompanied adolescent asylum seekers (UASC) (mean age 16 years) held in a restrictive reception centre with a group of 53 UASC housed in a routine facility, where they had more autonomy [50]. Participants completed the self-report Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL-25) [83, 84] and the Reactions of Adolescents to Traumatic Stress Questionnaire (RATS) [85]. Twenty UAM in the restrictive setting also completed a semi-structured questionnaire.

United Kingdom (UK)

Studies from the UK include both children and parents who had recently arrived and were seeking asylum and others who had lived for years in the UK and were detained prior to possible deportation.

In 2009 Lorek and colleagues published a small pilot study on the mental and physical health difficulties of 24 children aged between 3 months and 17 years, (median 4.7 years), in 16 families during detention in a British IDC [44]. The children were detained from 11 to 155 days (median 43 days). All 14 children aged over 5 years had lived and been educated in the UK for 18 months to 9 years before detention. The study used semi-structured clinical interviews undertaken by either a paediatrician and/or a psychologist, and reported SDQ results for 11 children and Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS), and Birleson Depression Self-rating Scale (DSRS) and the Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Revised Impact of Event Scale-13 item (R- IES-13) [86,87,88] for 6 children aged 7–11 years. Nine parents completed the Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation (CORE) [89].

A second UK study published in 2018, reports on 35 former detainees (21 male and 14 females) who were unaccompanied children (UAM) aged between 13 and 17 years (mean 15.8) when detained [51]. They all had their age disputed on arrival in the UK and were initially detained in adult facilities. The mean period of detention was 22.8 days (range 4–92 days). Participants were assessed on average 3 years after their detention. The study describes the legislative and policy environment in the UK, where until 2005, age assessment of asylum seekers was based solely on a cursory assessment by immigration officers, resulting in many minors being held in adult facilities. Participants completed the diagnostic clinical interview for DSM-IV (SCID-IV) for PTSD and Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) [74] and the self-report measures; Detention Experiences Checklist UK version [90], the RATS and the Stressful Life Events Questionnaire (SLE) [85].

Canada

Canadian researchers published two studies on the same cohort of 20 families who sought asylum in Canada and were detained. They used qualitative ethnographic and narrative approaches to understand children’s experience of detention. The mean time detained was 56.4 days and the study included 35 children aged 0–20 years during or after detention. The first study included ethnographic participant observation by the first author who visited the IDC weekly for 6 months; in-depth semi-structured interviews with parents and children aged 13–18 years; and play based interviews with children aged 6–12 years [60]. The second involved narrative enquiry and analysis to understand detained children’s experiences [61]. In this study ten children aged 3–13 years were invited to create ‘worlds’ using sand trays and to tell stories about what they had created. In-depth family interviews provided autobiographical context for the children’s narratives.

These 22 papers are now considered thematically.

The detention environment and children’s experiences of detention

Detailed information about the physical and psychological environment within which children and families were detained was collected and reported through observations from studies in detention centres in Hong Kong, Guantanamo Bay, Australia and Canada [49, 53, 54, 56, 57, 60]. The study undertaken with Cuban adolescents held in Guantanamo Bay [49] records their cumulative experiences of camp confinement in the context of prior loss and trauma. The Netherlands paper [50] and study of UAM detained by the UK [51] report on exposure to violence while detained, but there is less detailed information about the experience of living in detention in the recent US study [45].

The experience of detained children is privileged in five Australian and two Canadian papers through the inclusion of their drawings and words [53,54,55, 59,60,61, 65]. These ‘creations’ by detained children are particularly important, because they enable direct communication of their experience and counter prohibitions on the use of cameras and collection of images during visits to immigration detention centres. A thematic analysis of ‘sand tray worlds’ by children detained in Canada provides a particularly rich insight into children’s experience of detention [61]. Three broad themes were identified; ‘confinement and surveillance’ which included fences, barriers, stories of capture, confinement and separations; ‘loss of protection’, where the sand-tray worlds included threat and danger from human or animal figures and mixed representations of police and authority figures; and ‘human violence’, imagined and autobiographical. Everyday themes such as schooling, peers and magical protective forces usually seen in children’s play were generally absent [61].

These themes are echoed in the words and drawings of detained children included in the Australian papers and are articulated in a secondary thematic analysis of two drawings by detained children [65]. The first drawing contrasts the confinement of children behind a high fence with the perceived freedom and happiness of non-detained children represented playing and smiling. The second depicts children in individual cages even within the IDC and includes the words “we are in pne (pain?), we are in cage, we are in jail” [65] p.50. Both drawings show the confinement of the children, their sadness, suffering and isolation.

Evidence that daily life in closed detention includes dehumanizing experiences such as being identified by number not name, exposure to institutional and interpersonal violence including riots and in some contexts witnessing acts of self-harm is reported in studies from Hong Kong [56], Guantanamo Bay [49], the UK [51] and Australia [46, 47, 53,54,55, 57,58,59]. The Netherlands study of unaccompanied young people reports significantly more violent incidents in the restrictive than the open setting and more than half the unaccompanied youth reported a decline in their health and sense of safety while detained [50]. Canadian researchers describe that even when detained children were not exposed to violence and self-harm, “pervasive understimulation and the constant surveillance of the children and of their mothers transformed daily life into an experience of deprivation and powerlessness.” [60] p. 292.

At the time of these studies access to adequate health care, schooling and other potentially protective experiences was limited for children detained for immigration purposes in Hong Kong, the UK and Australia [44, 46, 47, 55, 56, 63, 64]. The cumulative adversities experienced by children who had been detained were identified in the Australian file audit by Hanes and colleagues using the R-ACE [64, 79]. All children recorded multiple adverse exposures prior to and during detention including witnessing violence and death. Access to school had been interrupted for 89.2% of children, particularly while detained [64].

The findings from these disparate studies confirm that in immigration detention children are exposed to institutional and interpersonal violence and are deprived of adequate developmental and protective experiences. “The gravity of the detention experience for these children is reinforced by the absence of stories of normality.” [61] p. 435.

Mental health findings

Despite the range of qualitative and quantitative methodological approaches used, elevated rates of psychological distress and disorder in children, adolescents and parents held in immigration facilities was reported in all studies, although rates of distress and disorder vary. The self-report measures are summarised in Table 2.

Quantitative mental health data—children and parents

Seven studies report quantitative data about children from mental health self-report measures completed by parents and/or older children (see Table 2). The recent cross-sectional US study using the SDQ found 10% of 425 children detained for 2 months, had elevated total difficulty scores, and probable PTSD was identified in 17% of 150 children on the PTSD-RI [45]. The authors conclude that 44% of children were significantly symptomatic on one SDQ subscale or the PTSD-RI. These rates are significantly above those identified in US Spanish speaking populations. Children who had a period of involuntary separation from their mothers during the immigration process had higher rates of emotional and total difficulty scores. Symptomatic children were likely to have been exposed to trauma in their home countries and during migration, and the authors conclude that detention in the US and lack of access to mental health care could have cumulative adverse consequences. The strengths of this study are the size of the sample and the inclusion of standardized parent and child self-report measures. A limitation in this as in other studies is the cross-sectional assessment of a ‘convenience sample’. The rates of mental disorder identified by MacLean and colleagues are lower than other quantitative studies.

In the study of Cuban children held by the US in Guantanamo Bay for 6–8 months [49] most children reported cumulative trauma pre, during and post arrival, and all had severe to very severe scores on the PTSDRI, with 94% of boys and 96% of girls scoring in the highest symptom category. A majority reported frequent crying, irritability, nightmares sleep and appetite disturbance. Half had secondary enuresis and 20% reported suicidal ideation and acts of self-harm. Adolescents reported “feeling dehumanized” and “treated like cattle”, particularly in the requirement to always wear an electronic ID bracelet [49] p.116.

In Australia, where average duration of detention ranged from 6 to 18 months, 75–100% of adults and children were identified as significantly symptomatic in the three studies reporting quantitative data [46,47,48]. Comorbid PTSD, depression and anxiety were commonly identified, as were elevated rates of suicidal ideation and self-harm including in preadolescent children [46,47,48]. In the clinical sample of 20 children in 10 families, all children had at least one parent with psychiatric illness and 100% of children aged over 6 years fulfilled criteria for both PTSD and MDD with suicidal ideation. Eight children (80%), including three preadolescents had self-harmed. Comorbid anxiety and persistent somatic symptoms were common. Similar findings were made in the self-report study with a population sample of 20 children in 10 families, where all adults and children met criteria for at least one psychiatric disorder and the authors estimated a threefold increase in psychiatric disorder for adults and tenfold increase for children while detained [47].

The UK cross-sectional pilot study of 11 children aged over 3 years detained for a median of 43 days [44], reports SDQ data that indicates 73% of children met criteria for psychiatric ‘caseness’. This is similar to a secondary analysis of SDQ data for 70 children held by Australia for a median of 209 days, where 75.7% of children had a high probability of suffering a psychiatric disorder [48]. In both studies rates of emotional and behavioral difficulties were high, including sleep problems, somatic complaints, poor appetite, emotional symptoms, and behavioral difficulties. The Australian study also reported K10 results showing rates of mental disorder resembling clinical populations with severe comorbid depression and anxiety in 85.7% of teenagers [48]. Parental mental health is discussed further below.

Qualitative studies

The quantitative findings are supported and given depth by papers that capture the circumstances and psychological state of detained parents and children through inclusion of children’s drawings and play, clinical vignettes and material from in depth interviews [49, 53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65]; case reports [59], and/or accounts from ethnographic or participant observation [57, 60].

As an example the early study of 603 Vietnamese children held in Hong Kong found that majority of children were “depressed and anxious”, presentations were “characterised by sadness, lack of energy and a disinterest in what is going on around them….they…are restless and have problems concentrating. Memories of distressing events intrude upon their thoughts.” [56] p. 2. Length of time in detention, prolonged uncertainty about resolution of asylum claims and caregiving arrangements were related to the severity of symptoms, with unaccompanied children faring worst. Significantly, the report notes that “the difference is one of degree. The wellbeing of all the children deteriorates over time, regardless of caregiving arrangements.” [56] p. 2. The report concludes that pre- and post-migration trauma, duration of detention, especially combined with parental separation resulted in high levels of psychological distress.

Mares and Zwi [54] identify “pervasive sadness and despair” in children and adults and “extreme fear about the future and the distress caused by daily ‘operational’ events that are experienced as cruel and humiliating”. They conclude “Children suffer the direct effects of the detention environment by being locked up, identified by number, exposed to violence and deprived of developmental opportunities including very limited access to education… [and]the indirect effects of parental mental illness, family separations and inadequately addressed health conditions.” [54] p.668.

The drawings, quotations and details of play from detained children include their experiences directly, and graphically communicate what they have seen, their distress and hopes and fears for the future, complementing other forms of evidence about the impact of immigration detention on children’s wellbeing and health.

Detention, parental mental health and parenting

For displaced children, being accompanied by family is shown to be protective [17], but this is influenced by family circumstances including parental mental state. There is established evidence that mental disorder can alter the quality of parenting and increase adversity for children, including in refugee populations [20].

Eleven papers record qualitative observations, some with clinical vignettes about the direct impact of immigration detention on family life [53, 54, 56,57,58, 60, 61] and four include quantitative data about parental mental health [44, 46,47,48].

The quantitative studies, which use different screening or diagnostic measures, identify high levels of distress and disorder in detained parents. All nine parents in a small UK study demonstrated high levels of generalised distress on the CORE [89], six had actively considered suicide and two were on suicide watch [44]. The Australian population study using the SCID-IV found all 14 adults met diagnostic criteria for at least one psychiatric disorder, several had comorbid illness and subjectively the majority felt unable to adequately care for their children [47]. In the clinical sample of 10 families assessed by a CAMHS team at least one adult in each family was diagnosed with serious mental disorder and several had been hospitalized after suicide attempts [46], and the study using the K10 with families detained on remote Christmas Island found that 83% of parents had symptoms of severe comorbid depression and anxiety [48].

Four papers mention forced separation from one or both parents during the reception and immigration process, and in different ways each study demonstrates the associated increase in children’s anxiety and distress [45, 54, 60, 61]. Authors of the recent US study of detained children [45] published a follow-up paper on the impact on children of family separations which was outside the time frame of this review [91]. This is part of a growing literature on the issue of forced family separations for immigration purposes [39, 92, 93].

In summary immigration detention of parents and children is shown to have negative impacts on the quality of family relationships, parenting and children’s wellbeing through pervasive institutional restrictions, undermining of parent’s capacity to provide for and protect their children. This is compounded by declining parental mental health and forced family separations. As Kronick et al. [60] conclude, “children should not be detained for immigration reasons and parents should not be detained without children.” [60] p.287.

Physical and developmental needs of infants and children

Infants and young children are rarely included in studies of refugee children despite their obvious vulnerability and the significant impact that adversity in early life can have on development [94, 95]. Six studies include information about this age group [44, 46, 48, 53, 54, 60].

A significant majority of detained parents had concerns about the health or development of their infants. One study utilizing multidisciplinary assessment identified developmental delay or emotional disturbance in a majority of preschool-age children [46] and several studies report the practical difficulties such as restricted supplies of infant products or formula, limited access to fresh food and poor hygiene while caring for infants in detention [44, 54, 60].

Physical, developmental and psychological health are interrelated in childhood, particularly in younger children. Complex and unmet physical health needs, poor nutrition, acute and chronic illnesses and lack of routine preventative services including vaccinations were identified in the UK pilot study [44], the file audits of detained children attending either an Emergency Department [63] or a refugee clinic [64], and are mentioned in four other Australian papers [46, 53, 55, 59].

Unaccompanied minors

There are complex pre and post-migration factors that increase the vulnerability of unaccompanied children held in restrictive settings. The included papers acknowledge potential resilience but overall identify the particular vulnerability of these young people while detained, with prior exposure to violence and loss compounded by administrative processes such as age assessment, detention with adults and a lack of support in negotiating migration processes [50, 51, 55, 56]. The only paper to specifically mention gender [50] identified higher rates of anxiety in unaccompanied young women than men in the restrictive setting. In Australia there is no independent guardian allocated to represent and advocate for the best interests of unaccompanied children [55]. The study of unaccompanied young people previously detained by the UK [51] found that all participants reported multiple stressful life events prior to detention and high levels of trauma while held in adult facilities. These included forced searches, aggression and violence from officers, violence between detainees and self-harm. For many participants the timing and content of their intrusive memories indicated that age dispute and detention with adults were causal in precipitating PTSD. Overall detaining unaccompanied children and adolescents is a breach of their human rights and compounds prior adversity including trauma and parental loss or separation. The age determination process, lack of an independent guardian, limited access to education or other meaningful activity, and delays in processing asylum claims were particularly harmful.

Post detention studies

Two quantitative studies recruited children or young people who had previously been detained [51, 52], and a Canadian paper includes children who were studied either during or post detention [61]. Rothe and colleagues report PTSD-RI scores from 87 Cuban children aged 6–17 years, 4–6 months after their detention [52]. A majority reported moderate to severe PTSD symptoms and 57% met criteria for PTSD on the PTSD-RI. A significant relationship was found between the number of prior stressors and severity of current symptoms. Older age and witnessing violence while detained were moderately associated with a continuing risk of PTSD. Their teachers completed the CBCL-TRF [81] and significantly underreported the children’s symptoms. The UK study assessed 35 young people an average of 3 years after their detention as unaccompanied minors and found severe, chronic mental health difficulties in 89% of the sample with the most common diagnoses being coorbid PTSD and Major Depression or PTSD alone [51]. The authors estimated rates of mental disorder on arrival in the UK and concluded that the experience of detention resulted in 29% of the sample developing PTSD and 23% MDD de novo, with a majority experiencing an exacerbation in pre-existing PTSD and/or MDD [51]. Kronick and colleagues also found continuing distress and preoccupation with experiences during detention in their qualitative Canadian studies [60, 61]. Despite very different populations and timeframes and methods, all three studies found that immigration detention had a lasting impact on mental health and identify the potential benefits of mental health screening after refugee resettlement.

The contribution of detention to the burden of mental disorder

Two studies use comparison samples of children and young people who are presumed to have similar premigration risks to identify the contribution of restrictive detention rather than other factors to the genesis and aggravation of mental disorder [50, 62]. Both identify significantly higher rates of disorder in those exposed to restrictive detention. Two studies retrospectively collect data about rates of disorder prior to detention and during or post detention. A study of detained families [47] estimated that mental disorder was increased threefold in adults and ten times in children during detention. A post detention study of UAM described above [51] estimated that detention resulted in new cases of PTSD or MDD in a quarter to a third of adolescents and deterioration in established mental illness in the others. These studies support the conclusion that restrictive detention in itself is pathogenic.

In summary, high rates of mental distress and disorder are identified in all studies of detained children and parents and can persist post detention. Restrictive detention is found to compound pre-existing vulnerabilities with rates of mental disorder higher than in children with similar risks who were not detained.

Ethical issues, human rights, and advocacy

Evidence about the restrictive environments within which children and families are detained, the poor mental health of detained children and parents and limited access to or effectiveness of health care are findings that raise professional and ethical issues for some authors.

Ten papers specifically referred to immigration detention of children as a breach of the detaining State’s human rights obligations [44, 46, 48, 51, 53,54,55, 60, 61, 65]. The politicised context and/or implications of the work are also identified [44, 49, 53, 57]. Inadequate access to health care, obstacles to providing adequate or effective interventions [44,45,46, 63], and the ethical dilemmas for and impact on involved clinicians [46, 59] are noted. The role of clinicians in advocacy for the best interests of detained children is specifically identified in several papers [44, 49, 51, 53, 58, 60, 61].

Strengths and limitations

This scoping review identified 22 papers of varying significance published between 1992 and May 2019 that provide original data about the mental health of children, parents and unaccompanied young people who were or had previously been held in restrictive immigration detention in six countries. The findings highlight the paucity of evidence and weakness of individual studies, about an increasingly common practice, (adminstrative detention of children and families for immigration purposes), that has significant health and human rights implications. This is an area of study with practical and ethical implications for clinicians, researchers and policy makers.

All individual studies have acknowledged methodological weaknesses. These are associated with cross-sectional analysis, small potentially unrepresentative samples, lack of control or comparison groups and the use of self-report or clinical approaches to mental health assessment with children and families who are incarcerated for immigration purposes. The quality of individual studies and the gaps in the knowledge base are a kind of evidence themselves of the many obstacles to research in this area, and the need for more of it [22,23,24, 72].

Therefore, a strength of the scoping review process is that it has enabled the collation of data from disparate sources collected in six countries and published over a 27-years span. Despite individual limitations, when considered together these studies build a compelling narrative about the experience, the consequences and cumulative adversity faced by children and parents held in restrictive detention by Australia, Canada, Hong Kong, the Netherlands, the UK and US. The evidence is consistent that children who are already vulnerable by virtue of their premigration experiences are exposed to further adversity and risk by restrictive reception policies. These studies report evidence that is inconvenient and which some governments have tried to deny or made it a crime to report [96]. The act of undertaking the research and publicising it is, therefore, inevitably political and politicised. Newman has written, “Researching asylum seekers and documenting high rates of suffering and mental health problems, by definition, makes a commentary on systems of detention and health care for this population” [23], p. 175.

Arguably the convergence of findings from multiple sources identified in this scoping review has the potential to increase the ‘truth’ value and validity of the findings and to enable a richer and more comprehensive description of the phenomena and the experiences under consideration [97]. The diversity of approaches to data collection and reporting can, therefore, be considered a strength, building a cumulative picture of the experience of immigration detention for children and parents and the impacts of this on mental health and family life. The studies that include children’s evidence in the form of drawings, play and words add a rich subjectivity to the findings.

The limitations of individual studies do not undermine the significance of this body of work. Considered together these studies identify the consequences of immigration detention from multiple perspectives, clarify possible areas for future study and should be used to inform changes in policy and practice.

Discussion

There are two major findings of this review. The first is that the literature on the mental health burden associated with immigration detention of children and families is limited and includes a diverse range of predominantly small cross-sectional studies. The challenges of research with displaced and refugee children are well documented [13, 25,26,27,28,29], and these are increased when researching children in immigration detention. The second finding is that despite these limitations there is consistency in the conclusions drawn from these papers and confirmed in broader systematic reviews [12,13,14], that immigration detention is a profoundly adverse reception experience for already vulnerable children. It is associated with rates of mental distress and disorder that in a majority of studies resemble clinical cohorts. These findings raise questions that require further study and elucidation. Practical and political circumstances make consent and access for longitudinal and participatory studies difficult and perhaps unethical to undertake.

In terms of future research there are questions that sit within a broader literature on the impact of cumulative and complex trauma about the relative contribution of restrictive detention to the identified burden of mental disorder in detained children. Child refugees who are not detained also have increased risk of mental distress and disorder [3, 10,11,12,13]. It is likely that multiple peri-migration and personal factors influence who is detained. As discussed, four papers attempt to address this question through use of comparison samples [50, 62], or by attempting an estimate of mental health burden premigration [47, 51]. This evidence would be strengthened by longitudinal follow-up of matched cohorts after resettlement such as those included in the study by Zwi and colleagues [62], where children with similar pre and peri-migration risks but diverse reception experiences are assessed and followed over time.

Exposure to violence, loss of a parent, being unaccompanied and uncertainty about migration status are consistently identified as increasing the vulnerability of refugee children to mental disorder [12, 13]. A majority of studies in this review obtained some information about pre and peri-migration experiences for children, particularly family separations, deaths and exposure to violence, and exposures while detained. Various methods were used [44, 47, 49, 51, 64]. Consistent approaches to collecting this information such as the R-ACE [79] have the potential to better document and allow comparison of risk and resilience factors specific to refugee populations.

Most studies of detained adults show that the number of people with mental disorder and the severity of that disorder increases with length of time detained [32]. There is conflicting evidence about whether this is true for children. The US study found that after 2 months in detention 44% of children were significantly symptomatic on one SDQ subscale or the PTSD-RI [45]. This compares with 75–100% of children having a high probability of mental disorder in Australian studies, where length of detention has regularly exceeded 6 months [46,47,48]. Canadian and UK studies confirm that even relatively short periods of detention resulted in many children becoming significantly symptomatic and at high risk of mental disorder [44, 60, 61]. Duration of detention, symptomatic self-selection (convenience versus clinical samples) and the degree of adverse exposure pre- and post-migration may account for differences in the rates of disorder identified. It is reasonable to conclude that immigration detention even for short periods is an adverse experience for children who are already vulnerable, and that rates and severity of mental distress and disorder increase with time detained and persist after detention.

From a clinical perspective there are questions about the adequacy and utility of brief self-report measures such as the SDQ in screening for mental disorder in children exposed to cumulative trauma and adversity at different developmental stages, and from extremely diverse backgrounds. Also it is unclear whether there are specific symptom profiles associated with psychopathology in detained children. Comorbidity was frequently identified in studies using self-report measures [44, 47, 49], and in the clinical sample of ten Australian families who underwent complex multidisciplinary assessment by a CAMHS team [46]. The symptoms of children and young people with cumulative past and current adverse exposures may not neatly fit standard diagnostic categories. As an example, the single case report included here [59] describes a child with symptoms that could be designated as Pervasive Refusal or Resignation Syndrome, a diagnosis not included in DSM or ICD classifications [98]. This is a potentially life threatening presentation of profound withdrawal that has been identified in clusters of refugee children in Sweden and more recently in children held by Australia for many years in offshore detention on Nauru [99,100,101].

Clarification of best approaches to mental health screening and assessment in this very diverse population would build a more coherent body of evidence about how best to identify children in need of mental health assessment and intervention on arrival in a host country, and after resettlement. The SDQ and the PDSD-RI are the most frequently used measures in studies included here and together they provide complementary information about both children’s overall functioning (SDQ), and more specific PTSD symptoms. Both measures have been widely used with children from diverse language and cultural backgrounds [102]. A tentative recommendation could be made that if screening measures are to be used in further research studies, there is a small body of work to build on using these measures.

An interesting finding from two Australian and one US study using SDQ data show that despite being highly symptomatic with overall rates of difficulties resembling clinical cohorts, detained children had higher prosocial scores and fewer peer difficulties than clinical populations or resettled refugee children [45, 48, 62]. It is possible that prosocial skills (consideration, kindness and capacity to share with peers) are an advantage in an environment where many parents are mentally unwell with reduced capacity to meet children’s needs. An alternative, also untested hypothesis is that in a circumstance of prolonged institutional neglect children become less discriminating in their interactions and sociability, akin to a form of attachment disorder, that is not distinguished from enhanced sociability on self-report screening such as the SDQ [103].

Further research is required to clarify the specific, interacting factors associated with both resilience and the development of psychopathology in children detained for immigration purposes.

An alternative to further studies to clarify the harms caused by harsh reception policies is to conclude that there is sufficient evidence that restrictive detention generates, exacerbates and perpetuates mental disorder in children and the adults who care for them. Instead research could be focused on development and evaluation of effective, humane and viable reception and resettlement alternatives focussing on prevention and early intervention with people who seek asylum, while identity and protection claims are assessed. Detention and prolonged uncertainty about visa status are factors that compound anxiety and delay recovery from past trauma. Evidence suggests that priorities for harm minimization include; avoiding ‘administrative detention’, apart from for the shortest possible time, particularly for children; processing claims fast and efficiently; minimising family separations; and supporting family reunification. Access to protective experiences such as schooling and independent health services are also very important.

From a mental health perspective there is a need for consistent approaches to screening of children at the time of their arrival in reception countries, during any incarceration and afterwards to determine who requires comprehensive assessment and targeted mental health intervention as well as other practical and psychosocial supports [104]. There is increasing evidence about the effectiveness of interventions with and for refugee children and families during resettlement [105, 106] and the need for adequate training and support of clinicians working in this area.

There is little or no evidence about the effectiveness or appropriateness of therapeutic interventions for children, while they are held in restrictive detention. Kronick and colleagues [61] used sand-tray work to collect data about children’s experiences of detention and suggest this as a safe way for them to explore and express their experiences and anxieties. There is evidence in several of the included papers that children’s health and mental health needs are complex and that health and mental health care provision in detention was inadequate [44, 46, 63]. Several of the Australian papers raise questions about the obstacles to providing independent and effective mental health treatment to children and families while they are held in a developmentally inadequate and traumatizing environment, and there is administrative interference with implementation of clinical decisions, and/or where clinicians face a dual loyalty conflict given their contractual relationship with the detention provider [46, 107, 108]. These factors raise questions about how best to provide health and mental health care to children and families while they are detained in restrictive settings, particularly when health care services are not independent.

The conclusion that immigration detention of children involves multiple human rights violations and is never in the child’s best interests is confirmed in the studies included here, and in multiple other inquiries and reviews [7, 9, 72, 109, 110]. The mental health findings, the human rights implications, and evidence that health care is compromised in restrictive circumstances, raise ethical issues about the role of clinicians and researchers working with children held in a traumatizing and inadequate environment, where their best interests are not prioritized. The role of clinicians in advocacy against restrictive policies that cause identifiable harm to children, and for alternative approaches to reception of children and adults who seek asylum is raised in almost half of the included papers. There are arguments that clinicians have an obligation to advocate against implementation of policies that cause harm to a group of people as a consequence of their visa status, and that advocacy is the most effective action that clinicians take [112]. There is a growing body of literature about the role of clinicians in advocacy for the best interests of detained children that that requires acknowledgment but is not possible to consider in detail here. This literature has predominantly come from Australia but also includes international commentary [72, 110,111,112,113,114]. There is a logic (underpinned by child protection, public health and human rights principles) to the conclusion that if care and protection cannot be provided to a child or children in their current environment, then they should be moved to safer circumstances, and other children should also be protected from the identified risks.

Conclusion

Qualitative and quantitative studies identified in this Scoping Review build a rich and detailed body of information about the multiple negative consequences of immigration detention for children and families. Restrictive detention is a particularly harmful reception experience for child asylum seekers who have already faced cumulative adversity during displacement and flight. Parenting is undermined directly in the detention environment and by parental mental illness, and there are few protective factors. All studies found elevated rates of mental disorder in detained children after even short periods, and duration of detention appears to be associated with more children becoming symptomatic and unwell. Immigration detention is associated with multiple human rights violations and compromised access to health care. These human rights and public health concerns raise ethical challenges for clinicians and researchers. Alternatives reception policies are available and reception countries should aim to support rather than exacerbate the wellbeing of children who seek asylum. Clinicians and researchers have a key role in advocating for the care and protection of vulnerable children, independent of their visa status. The development and evaluation of alternatives to restrictive reception policies are a priority.

References

UNHCR (2020) Figures at a glance. United Nations high commissioner for refugees. https://www.unhcr.org/en-au/figures-at-a-glance.html. Accessed 19 Jul 2020

UNHCR (2019) Global trends; forced displacement in 2018. UNHCR, Geneva

Hodes M, Melisa Mendoza V, Anagnostopoulos D, Triantafyllou K, Abdelhady D, Weiss K, Koposov R, Cuhadaroglu F, Hebebrand J, Skokauskas N (2018) Refugees in Europe: national overviews from key countries with a special focus on child and adolescent mental health. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 27(4):389–399

Silove D, Ventevogel P, Rees S (2017) The contemporary refugee crisis: an overview of mental health challenges. World Psychiatry 16(2):130–139

Silove D, Austin P, Steel Z (2007) No refuge from terror: the impact of detention on the mental health of trauma-affected refugees seeking asylum in Australia. Transcultural Psychiatry 44(3):359–393

Sampson R, Mitchell G (2013) Global trends in immigration detention and alternatives to detention: practical, political and symbolic rationales. J Migrat Hum Secur 1:97–121

Dudley M, Steel Z, Mares S, Newman L (2012) Children and young people in immigration detention. Curr Opin Psychiatry 25(4):285–292

Newman L, Steel Z (2008) The child asylum seeker: psychological and developmental impact of immigration detention. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 17(3):665–683

AHRC (2014) The forgotten children: national inquiry into children in immigration detention. Australian Human Rights Commission, Sydney

Bronstein I, Montgomery P (2011) Psychological distress in refugee children: a systematic review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 14(1):44–56

Lustig SL, Kia-Keating M, Knight WG, Geltman P, Ellis H, Kinzie DJ, Keane T, Saxe GN (2004) Review of child and adolescent refugee mental health. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 43(1):24–36

Fazel M, Reed RV, Panter-Brick C, Stein A (2012) Mental health of displaced and refugee children resettled in high-income countries: risk and protective factors. The Lancet 379(9812):266–282

Reed RV, Fazel M, Jones L, Panter-Brick C, Stein A (2012) Mental health of displaced and refugee children resettled in low-income and middle-income countries: risk and protective factors. The Lancet 379(9812):250–265

Kien C, Sommer I, Faustmann A, Gibson L, Schneider M, Krczal E, Jank R, Klerings I, Szelag M, Kerschner B, Brattstrom P, Gartlehner G (2019) Prevalence of mental disorders in young refugees and asylum seekers in European Countries: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 28(10):1295–1310

Vossoughi N, Jackson Y, Gusler S, Stone K (2018) Mental health outcomes for youth living in refugee camps: a review. Trauma Violence Abuse 19(5):528–542

El Baba R, Colucci E (2018) Post-traumatic stress disorders, depression, and anxiety in unaccompanied refugee minors exposed to war-related trauma: a systematic review. Int J Culture Mental Health 11(2):194–207

Muller LRF, Buter KP, Rosner R, Unterhitzenberger J (2019) Mental health and associated stress factors in accompanied and unaccompanied refugee minors resettled in Germany: a cross-sectional study. Child Adolescent Psychiatry Mental Health 13:8

Miles EM, Narayan AJ, Watamura SE (2019) Syrian caregivers in perimigration: a systematic review from an ecological systems perspective. Transl Issues Psychol Sci 5(1):78–90

LeBrun A, Hassan G, Boivin M, Fraser S-L, Dufour S, Lavergne C (2015) Review of child maltreatment in immigrant and refugee families. Can J Public Health 106(7):eS45–eS56

Bryant RA, Edwards B, Creamer M, O'Donnell M, Forbes D, Felmingham KL, Silove D, Steel Z, Nickerson A, McFarlane AC (2018) The effect of post-traumatic stress disorder on refugees' parenting and their children's mental health: a cohort study. Lancet Public Health 3(5):e249–e258

Sim A, Fazel M, Bowes L, Gardner F (2018) Pathways linking war and displacement to parenting and child adjustment: a qualitative study with Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Soc Sci Med 200:19–26

Zion D (2013) On secrets and lies: dangerous information, stigma and asylum seeker research. In: Block K, Riggs E, Haslam N (eds) Values and vulnerabilities: the ethics of research with refugees and asylum seekers. Australian Academic Press, Bowen Hills, pp 191–206

Newman L (2013) Researching immigration detention: documenting damage and ethical dilemmas. In: Block K, Riggs E, Haslam N (eds) Values and vulnerabilities: the ethics of research with refugees and asylum seekers. Australian Academic Press, Bowen HIlls, pp 173–190

Kronick R, Cleveland J, Rousseau C (2018) “Do you want to help or go to war?”: Ethical challenges of critical research in immigration detention in Canada. J Soc Polit Psychol 6(2):644–660

Ziersch A, Due C, Arthurson K, Loehr N (2017) Conducting ethical research with people from asylum seeker and refugee backgrounds. In: Liamputtong P (ed) Handbook of research methods in health social sciences. Springer, Singapore, pp 1–19

Block K, Warr D, Gibbs L, Riggs E (2012) Addressing ethical and methodological challenges in research with refugee-background young people: reflections from the field. J Refugee Stud 26(1):69–87

Due D, Riggs DW, Augoustinos M (2014) Research with children of migrant and refugee backgrounds: a review of child-centered research methods. Child Indic Res 7(1):209–227

Hopkins P (2008) Ethical issues in research with unaccompanied asylum-seeking children. Children's Geographies 6(1):37–48

Rousseau C (1993) The place of the unexpressed: ethics and methodology for research with refugee children. Can Ment Health 41(4):12–16

Fazel M, Wheeler J, Danesh J (2005) Prevalence of serious mental disorder in 7000 refugees resettled in western countries: a systematic review. The Lancet 365(9467):1309–1314

Robjant K, Hassan R, Katona C (2009) Mental health implications of detaining asylum seekers: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry 194(4):306–312

von Werthern M, Robjant K, Chui Z, Schon R, Ottisova L, Mason C, Katona C (2018) The impact of immigration detention on mental health: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 18(1):382

Baggio S, Gonçalves L, Heeren A, Heller P, Gétaz L, Graf M, Rossegger A, Endrass J, Wolff H (2020) The mental health burden of immigration detention: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Criminology 2:219

Cleveland J, Rousseau C (2013) Psychiatric symptoms associated with brief detention of adult asylum seekers in Canada. Can J Psychiatry 58(7):409–416

Arksey H, O'Malley L (2005) Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 8(1):19–32

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien K, Colquhoun H, Kastner M, Levac D, Ng C, Sharpe JP, Wilson K (2016) A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 16(1):15

Peters M, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB (2015) Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthcare 13(3):141–146

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MJ, Horsley T, Weeks L (2018) PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 169(7):467–473

Wood LC (2018) Impact of punitive immigration policies, parent-child separation and child detention on the mental health and development of children. BMJ Paediatrics Open 2(1):e000338

Musalo K, Lee E (2017) Seeking a rational approach to a regional refugee crisis: lessons from the summer 2014 “surge” of Central American women and children at the US-Mexico border. J Migrat Hum Secur 5(1):137–179

Sriraman NK (2019) Detention of immigrant children—a growing crisis. What is the Pediatrician's role? Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 49(2):50–53

UNHCR (2014) Options for governments on care arrangements and alternatives to detention for children and families. UNHCR, Geneva

Hamilton C, Anderson K, Barnes R, Dorling K (2011) Administrative detention of children: a global report. United Nations Children’s Fund, New York

Lorek A, Ehntholt K, Nesbitt A, Wey E, Githinji C, Rossor E, Wickramasinghe R (2009) The mental and physical health difficulties of children held within a British immigration detention center: a pilot study. Child Abuse Negl 33(9):573–585

MacLean SA, Agyeman PO, Walther J, Singer EK, Baranowski KA, Katz CL (2019) Mental health of children held at a United States immigration detention center. Soc Sci Med 230:303–308

Mares S, Jureidini J (2004) Psychiatric assessment of children and families in immigration detention–clinical, administrative and ethical issues. Aust N Z J Public Health 28(6):520–526

Steel Z, Momartin S, Bateman C, Hafshejani A, Silove DM, Everson N, Roy K, Dudley M, Newman L, Blick B, Mares S (2004) Psychiatric status of asylum seeker families held for a protracted period in a remote detention centre in Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health 28(6):527–536

Mares S (2016) The mental health of children and parents detained on Christmas Island: secondary analysis of an Australian Human Rights Commission data set. Health Hum Rights J 18(2):219–232

Rothe EM, Castillo-Matos H, Busquets R (2002) Posttraumtic stress symptoms in Cuban adolescent refugees during camp confinement. Adolesc Psychiatry 26:97–124

Reijneveld SA, de Boer JB, Bean T, Korfker DG (2005) Unaccompanied adolescents seeking asylum: poorer mental health under a restrictive reception. J Nerv Ment Dis 193(11):759–761

Ehntholt KA, Trickey D, Harris HJ, Chambers H, Scott M, Yule W (2018) Mental health of unaccompanied asylum-seeking adolescents previously held in British detention centres. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 23(2):238–257

Rothe EM, Lewis J, Castillo-Matos H, Martinez O, Busquets R, Martinez I (2002) Posttraumatic stress disorder among Cuban children and adolescents after release from a refugee camp. Psychiatr Serv 53(8):970–976

Mares S, Newman L, Dudley M, Gale F (2002) Seeking refuge, losing hope: parents and children in immigration detention. Aust Psychiatry 10(2):91–96

Mares S, Zwi K (2015) Sadness and fear: The experiences of children and families in remote Australian immigration detention. J Paediatr Child Health 51(7):663–669

Zwi K, Mares S (2015) Stories from unaccompanied children in immigration detention: a composite account. J Paediatr Child Health 51(7):658–662

McCallin M (1992) Living in detention: a review of the psychological well-being of Vietnamese children in the Hong Kong detention centres. International Catholic Child Bureau, Geneva

Sultan A, O'Sullivan K (2001) Psychological disturbances in asylum seekers held in long term detention: a participant-observer account. Med J Aust 175(11–12):593–596

Essex R, Govintharajah P (2017) Mental health of children and adolescents in Australian alternate places of immigration detention. J Paediatr Child Health 53(6):525–528

Zwi K, Herzberg B, Dossetor D, Field J (2003) A child in detention: dilemmas faced by health professionals. Med J Aust 179(6):319–322

Kronick R, Rousseau C, Cleveland J (2015) Asylum-seeking children's experiences of detention in Canada: a qualitative study. Am J Orthopsychiatry 85(3):287–294

Kronick R, Rousseau C, Cleveland J (2018) Refugee children’s sandplay narratives in immigration detention in Canada. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 27(4):423–437

Zwi K, Mares S, Nathanson D, Tay AK, Silove D (2017) The impact of detention on the social–emotional wellbeing of children seeking asylum: a comparison with community-based children. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 27(4):411–422

Deans AK, Boerma CJ, Fordyce J, De Souza M, Palmer DJ, Davis JS (2013) Use of Royal Darwin Hospital emergency department by immigration detainees in 2011. Med J Aust 199(11):776–778

Hanes G, Chee J, Mutch R, Cherian S (2019) Paediatric asylum seekers in Western Australia: identification of adversity and complex needs through comprehensive refugee health assessment. J Paediatr Child Health 55(11):1367–1373

Lenette C, Karan P, Chrysostomou D, Athanasopoulos A (2017) What is it like living in detention? Insights from asylum seeker children’s drawings. Aust J Hum Rights 23(1):42–60

Global Detention Project (2019) Annual report 2019. Global Detention Project, Geneva

Phillips J (2015) Asylum seekers and refugees: what are the facts? (trans: Library P). Research Paper Series 2014–15. Department of Parliamentary Services, Parliament of Australia Canberra

Dutton P (2018) An Interview with the Honourable Peter Dutton, Australia's Minister of Home Affairs. Int Migr 56(5):5–10

Commonwealth of Australia (2017) Serious allegations of abuse, self-harm and neglect of asylum seekers in relation to the Nauru Regional Processing Centre, and any like allegations in relation to the Manus Regional Processing Centre (trans: Affairs LaC, References Committee). Senate, Canberra

Amnesty International (2016) Australia: appalling abuse, neglect of refugees on Nauru. Amnesty International, London

Mares S (2016) Fifteen years of detaining children who seek asylum in Australia—evidence and consequences. Aust Psychiatry 24(1):11–14

Mares S (2020) Mental health consequences of detaining children who seek asylum in Australia and the implications for health professionals: a mixed methods study (2002–2019). Doctorate by Prior Publication. Flinders University, Adelaide

Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan N (1997) Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36(7):980–988

First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J (1997) Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders (SCID-IV). American Psychiatric Press, New York

Goodman R (2001) Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 40(11):1337–1345

Brooks RT, Beard J, Steel Z (2006) Factor structure and interpretation of the K10. Psychol Assess 18(1):62–70

Zwi K, Woodland L, Williams K, Palasanthiran P, Rungan S, Jaffe A, Woolfenden S (2018) Protective factors for social-emotional well-being of refugee children in the first three years of settlement in Australia. Arch Dis Child 103(3):261–268

Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, Walker JD, Whitfield C, Perry BD, Dube SR, Giles WH (2006) The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 256(3):174–186

Hanes G, Sung L, Mutch R, Cherian S (2017) Adversity and resilience amongst resettling Western Australian paediatric refugees. J Paediatr Child Health 53(9):882–888

Pynoos RS (1992) Scoring and interpretation of the post-traumatic stress disorder reactive index (PTSDRI), Department of Psychiatry. University of California, Los Angeles

Achenbach TM, Ruffle TM (2000) The Child Behavior Checklist and related forms for assessing behavioral/emotional problems and competencies. Pediatr Rev 21(8):265–271

Global Detention Project (2017) United States immigration detention. Global Detention Project https://www.globaldetentionproject.org/countries/americas/united-states. Accessed 16 Jul 2020

Ventevogel P, De Vries G, Scholte WF, Shinwari NR, Faiz H, Nassery R, van den Brink W, Olff M (2007) Properties of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (HSCL-25) and the Self-Reporting Questionnaire (SRQ-20) as screening instruments used in primary care in Afghanistan. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 42(4):328–335