Abstract

We performed an updated review of the available literature on weight gain and increase of body mass index (BMI) among children and adolescents treated with antipsychotic medications. A PubMed search was conducted specifying the following MeSH terms: (antipsychotic agents) hedged with (weight gain) or (body mass index). We selected 127 reports, including 71 intervention trials, 42 observational studies and 14 literature reviews. Second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), in comparison with first-generation antipsychotics, are associated with a greater risk for antipsychotic-induced weight gain although this oversimplification should be clarified by distinguishing across different antipsychotic drugs. Among SGAs, olanzapine appears to cause the most significant weight gain, while ziprasidone seems to cause the least. Antipsychotic-induced BMI increase appears to remain regardless of the specific psychotropic co-treatment. Children and adolescents seem to be at a greater risk than adults for antipsychotic-induced weight gain; and the younger the child, the higher the risk. Genetic or environmental factors related to antipsychotic-induced weight gain among children and adolescents are mostly unknown, although certain genetic factors related to serotonin receptors or hormones such as leptin, adiponectin or melanocortin may be involved. Strategies to reduce this antipsychotic side effect include switching to another antipsychotic drug, lowering the dosage or initiating treatment with metformin or topiramate, as well as non-pharmacological interventions. Future research should avoid some methodological limitations such as not accounting for age- and sex-adjusted BMI (zBMI), small sample size, short period of treatment, great heterogeneity of diagnoses and confounding by indication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the last two decades antipsychotics are increasingly prescribed to children and adolescents in many countries [1]. In particular, there has been a widespread use of second generation antipsychotic (SGA) treatment in children and adolescents with diagnosis of several psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or disruptive conduct disorders. This rise in SGA prescription in youth is mainly not only due to lower rates of extrapyramidal side effects, but also to increased diagnosis of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in youth (data obtained from the abstract of a review written in Hebrew) [49].

Among children and adolescents, weight gain or increase of body mass index (BMI) emerge as one of the most relevant side effects of SGA, with an ensuing risk of type II diabetes, cardiovascular morbidity and metabolic syndrome [34, 50]. The prevalence of overweight among hospitalised children and adolescents with exposure to SGAs is triple that of national norms in the United States [127]. In addition, it seems likely that the young are more susceptible to antipsychotic-induced weight gain than adults [30, 34, 49], which may be a frequent reason for non-compliance and for discontinuation of the antipsychotic treatment [63]. An excessive BMI among children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders may have other deleterious effects such as stigmatisation and further social withdrawal.

The literature on antipsychotic-induced weight or BMI increase among children and adolescents seems to be incomplete, since it usually is secondary to the main focus of research. In addition, most studies are hampered by limitations such as heterogeneity of diagnoses, small sample size, short period of treatment, confounding by indication [110] or not adjusting for BMI z score (standardised BMI, adjusted by age and sex, or zBMI).

The aim of this study was to review the weight gain or BMI increase among children and adolescents treated with antipsychotics in observational and intervention studies. We conclude with directions for future research.

Methods

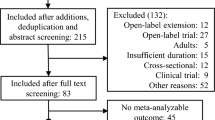

We conducted a paediatric literature review by searching in PubMed database—without any limit regarding date of publication, until the end of 2012—for reviews, cross-sectional or prospective observational studies and intervention trials specifying the following MeSH search terms: (antipsychotic agents) hedged with (weight gain) or (body mass index). We included studies that investigated the relationship between antipsychotic medications and BMI increase in all children and adolescents (from 0 to 18 years). The principal exposure measure was antipsychotic agents, and we took weight gain or BMI increase as the outcome. We excluded comments, letters, case studies, animal studies and studies in which the sample included adults or the weight gain or BMI increase was not one of the outcome variables. In addition, a naturalistic study on HIV patients with psychiatric symptoms [91] was excluded.

After excluding studies that did not match our selection criteria, we analysed with 127 studies, including 14 literature reviews, 71 intervention trials and 42 observational studies.

Results

The main features and results (including the number of subjects, type and duration of each study) of observational studies, intervention trials and literature reviews are respectively summarised in Tables 1, 2 and 3. In most of these studies, antipsychotic-induced gain or BMI increase was not the main goal of research, but rather a secondary result usually within the context of antipsychotic side effects. We categorised the results in three main sections: (1) effect of antipsychotic drug on weight or BMI; (2) predisposing factors; and (3) treatment of antipsychotic-induced weight gain or BMI increase.

Effect of antipsychotic drug on weight or BMI

First generation versus SGAs

A meta-analysis of schizophrenia children and adolescents treated with antipsychotics showed that first generation antipsychotics (FGAs) appeared to cause less weight gain than SGAs (the average weight gain in patients treated with FGAs was 1.4 kg compared to 4.5 kg for those treated with SGAs) [6]. In an open-label study of 50 adolescent inpatients who were followed for 8–12 weeks, mean weight gain ± standard deviation (SD) was significantly higher for the olanzapine group (7.2 ± 6.3 kg) than for the risperidone (3.9 ± 4.8 kg) and haloperidol (1.1 ± 3.3 kg) groups [132]. The same three antipsychotics were assessed in an 8-week double-blind randomised study among 50 children and adolescents [146] and, again, olanzapine caused significantly more weight gain (7.1 ± 4.1 kg) than risperidone (4.9 ± 3.6 kg) or haloperidol (3.5 ± 3.7 kg). In this study [146] participants treated with haloperidol gained weight at the slowest rate (0.54 kg/week), while those treated with the atypicals gained more quickly (risperidone 0.77 kg/week and olanzapine 0.99 kg/week), although the differences were not statistically significant. Further studies comparing weight gain or BMI increase between FGAs and SGAs reported a higher increase of weight or BMI among those treated with SGAs [76, 93, 145]. Nevertheless, other authors have not replicated these results. In a randomised, double-blind trial involving 116 youths on olanzapine, risperidone or molindone [56], weight gain was more frequent with olanzapine and risperidone than with molindone during the acute trial (8 weeks), but no significant differences remained during the maintenance trial (8–44 weeks). In addition, in a retrospective study of 109 schizophrenia early-onset adolescents treated with antipsychotics and followed for 6 weeks, there was no significant difference in weight gain at the endpoint between those on SGA (olanzapine, risperidone, ziprasidone or clozapine) and those on FGA (haloperidol, perphenazine or sulpiride) [85]. This study [85] found that (1) weight gain in patients on SGA, in comparison with those on FGA, was significantly higher during the first week of treatment but lower (although non-significantly) during the second and third week of treatment; and (2) in the last 3 weeks of the 6-week observation period, patients on FGA stabilised at the weight reached at week 3, whereas patients on SGAs continued increasing their weight. In contrast, a 24-week open-label study of 28 children and adolescents with autistic disorder treated with risperidone or haloperidol [73] showed a rapid weight gain in both treatment groups at the beginning of the study, then weight gain stopped after week 12 of the risperidone treatment, yet in the haloperidol group weight continued to increase until the week 24. However, both studies [73, 85] had the limitation of quite small sample sizes in their arms.

Nevertheless, there is growing recognition that the polarised dichotomisation of FGAs versus SGAs is an oversimplification since the risk potential for weight gain is heterogeneous within both antipsychotic classes [103].

Type of SGA

In paediatric populations, particularly in antipsychotic-naïve patients, weight gain may be a side effect common to all SGAs [31], as illustrated by a retrospective chart review conducted for all child and adolescent psychiatry emergency admissions over 2.5 years [126], where the mean zBMI was higher in the SGA-treated (n = 68) than in the SGA-naïve group (n = 99) (mean difference 0.81, 95 % CI = 0.46–1.16). Notwithstanding, the magnitude of antipsychotic-induced weight gain seems to differ depending on the SGA [39]. A long non-randomised SGA treatment involving 205 children and adolescents led to weight increases by 8.5 kg (95 % CI = 7.4–9.7 kg) among patients on olanzapine, by 6.1 kg (95 % CI = 4.9–7.2 kg) among patients on quetiapine, by 5.3 kg (95 % CI = 4.8–5.9 kg) among those on risperidone, and by 4.4 kg (95 % CI = 3.7–5.2 kg) among those on aripiprazole, compared with the minimal weight change of 0.2 kg (95 % CI = −1.0 to 1.4 kg) in the untreated comparison group [34]. In a meta-analysis including 24 trials of 3,048 paediatric patients with varying ages and diagnoses [40], olanzapine was associated with the greatest weight gain (3.45 kg; 95 % CI = 2.9–3.9), followed by risperidone (1.76 kg; 95 % CI = 1.2–2.2), quetiapine (1.43 kg; 95 % CI = 1.1–1.6), aripiprazole (0.79 kg; 95 % CI = 0.54–1.04) and ziprasidone (−0.04 kg; 95 % CI = −0.38 to 0.30). According to this study [40], aripiprazole is not devoid of significant weight gain among patients with autistic disorder (between 1.3 and 2.0 kg), who are younger and probably less exposed to antipsychotics previously.

Another review covering 34 studies and 2,719 youths with psychotic or bipolar spectrum disorders and treated with SGAs showed a mean weight gain ranging from 3.8 to 16.2 kg with olanzapine (n = 353), from 0.9 to 9.5 kg with clozapine (n = 97), from 1.9 to 7.2 kg with risperidone (n = 571), from 2.3 to 6.1 kg with quetiapine (n = 133) and from 0 to 4.4 kg with aripiprazole (n = 451) [64]. Similar results were found in a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials [129] which revealed that mean weight gain, compared with placebo, was the highest for olanzapine, 3.47 kg (95 % CI = 2.94–3.99), followed by risperidone [1.72 kg (95 % CI = 1.17–2.26)], quetiapine [1.41 kg (95 % CI = 1.10–1.81)] and aripiprazole [0.85 kg (95 % CI = 0.58–1.13)]. Another recent meta-analysis focusing on short-term (3–12 weeks) controlled studies showed that, compared with placebo, significant weight gain were observed among patients on olanzapine [3.99 kg (95 % CI = 3.17–4.84)], risperidone [2.02 kg (95 % CI = 1.39–2.66)], quetiapine [1.74 kg (95 % CI = 0.99–2.5)] and aripiprazole [0.89 kg (95 % CI = 0.26–1.51)] [27]. In a naturalistic study comparing treatment with clozapine, olanzapine and risperidone [61], the average weight gain after 6 weeks of treatment was significantly higher with olanzapine (4.6 ± 1.9 kg) than with risperidone (2.8 ± 1.3 kg) or clozapine (2.5 ± 2.9 kg). However, some small sample studies were not able to confirm these results [87, 120].

A number of studies indicated that weight gain associated with quetiapine is lower than with olanzapine or risperidone. A 6-month follow-up study of 66 children and adolescents on risperidone, olanzapine or quetiapine, found that, at the endpoint, there was a significant increase in zBMI in patients receiving olanzapine (p < 0.001) or risperidone (p = 0.008) but not in patients receiving quetiapine (p = 0.14) [65]. Similarly, a review including 24 placebo-controlled trials showed that the numbers-needed-to-harm for weight gain ≥7 % in youth with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia was 9 (CI = 7–14) for quetiapine, 6 (CI = 5–8) for risperidone and 3 (CI = 3–4) for olanzapine [103]. A double-blind controlled trial showed significant increase in weight and BMI among patients on olanzapine or quetiapine [4] although those on olanzapine gained significantly more weight than those on quetiapine (15.5 vs. 5.5 kg, p < 0.001). In contrast, a small sample randomised trial found that the percentage of patients with >10 % weight gained to be 27 % for quetiapine and 9 % for risperidone, though the difference did not reach statistical significance [148].

Olanzapine

Several naturalistic [25, 76, 95, 112, 128], open-label [4, 47, 66, 82, 94, 116, 121, 131, 136] and doubled-blind controlled trials [84, 97, 145] have demonstrated that significant weight gain is associated to treatment with olanzapine in children and adolescents (Tables 1, 2). Olanzapine seems to be the SGA that causes the most frequent and intense weight gain [4, 25, 34, 40, 62, 65, 132, 145]. A review of the literature from 1996 to 2004 on the indications and adverse reactions of olanzapine in children and adolescents with psychiatric illness showed that the most prominent adverse reaction was excessive weight gain, even more so than in adult patients treated with olanzapine [68]. Olanzapine was associated with extreme long-term weight gain in children and adolescents, much higher than that expected in adults [63]. A long-term (at least 24 weeks) naturalistic study found that the percentage of olanzapine-treated adolescents (n = 179) with ≥7 % mean weight gain was 89 % compared with 55 % in adults (n = 4,280) [99]. The weight gain was associated with an increase in caloric intake, without change in diet composition [76]. A clinical observation of 15 youths (age range, 6–13 years) with childhood-onset schizophrenia showed no significant weight gain during their short period of hospitalisation (mean of 11 days) under treatment with olanzapine (dose range, 5–20 mg/day) [144].

There have been few olanzapine serum concentration studies among children and adolescents. In a study that included 85 patients attending a child and adolescent psychiatric hospital [11], BMI and other variables such as olanzapine daily dose, number of co-medications, age and post-dose interval had a significant influence on the intra-individual variability of dose-corrected olanzapine serum concentrations (all p < 0.001).

Risperidone

Treatment with risperidone in children and adolescents has been related to significant weight gain in several in naturalistic [67, 69, 74, 107, 108, 149], open-label [8, 18, 54, 81, 117, 122, 124, 133, 155] and doubled-blind controlled studies [2, 19, 57, 102, 115, 123, 143, 147]. In contrast, two double-blind placebo-controlled trials involving small samples [7, 153] showed that the mean weight change was not significantly different between risperidone and placebo groups after 4 weeks. Meanwhile, a retrospective chart review of children and adolescents with disruptive behaviour disorder [111] and a low dose range of risperidone (0.3–0.9 mg/day) showed that only 12.5 % of patients (3/24) had a >10 % weight gain.

Weight or BMI changes induced by risperidone may tend to stabilise in long-term therapy. In a 2-year open-label trial of 48 children and adolescents (range age, 6–15 years) on risperidone (1–4 mg/day), zBMI changes stabilised after the first 3–6 months of therapy and did not increase beyond normal growth thereafter [133]. In addition, weight gain during risperidone treatment may reverse after discontinuation, as reported in a prospective longitudinal study of 24 months [101].

Research concerning a dose–response effect between risperidone and weight gain is unclear. On the positive side, in a double-blind controlled trial involving 257 schizophrenia adolescents [80], mean change in body weight was significantly higher for risperidone regimen A (1.5–6.0 mg/day) than for risperidone regimen B (0.15–0.6 mg/day): 3.2 ± 3.4 vs. 1.7 ± 3.2 kg. However, other studies did not support a dose–response relationship [79, 93, 108]. In a 3-week double-blind controlled trial of 169 patients with acute mania which compares placebo, risperidone in lower dose (0.5–2.5 mg/day) and risperidone in higher dose (3–6 mg/day), mean weight gain was 0.7 ± 1.9, 1.9 ± 1.7 and 1.4 ± 2.4 kg, respectively [79].

Weight gain with risperidone may be relevant beyond its metabolic implications. The metabolism of risperidone to 9-hydroxyrisperidone increased with body fat; a higher zBMI predicted a higher 9-hydroxyrisperidone concentration [23]. Among children with autistic disorder, those on risperidone who gained more weight improved less from their irritability [9]. Unfortunately, weight gain from risperidone treatment could not be predicted from baseline weight and BMI or other characteristics such as concomitant medication use, sex, age and pubertal status [108].

Quetiapine

Several open-label trials [43, 90, 106, 114, 141] and a naturalistic study [140] have reported significant weight gain associated with quetiapine treatment among children and adolescents. Open-label trials have shown average weight gains of 4.1 kg (3.4 kg after adjustment by age expected weight gain) over 8 weeks [141], 6.2 kg over 12 weeks [140], 2.9 kg over 16 weeks [106] and 2.3 kg over 88 weeks [114]; in addition, a weight gain of 4.4 kg in a 4-week double-blind study [45]. In contrast, other studies reported lower weight gain, such as 2.3 kg in an 8-week randomised placebo-controlled trial [44] and 1.4 kg in a 12-week open-label study where no patient discontinued treatment because of weight gain [43].

Clozapine

Clozapine has been associated with weight gain among children and adolescents in naturalistic studies [63, 113] as well as in randomised trials [100, 142]. Prospective studies among paediatric inpatients have shown average weight gains of 3.8 over 8 weeks, 6.9 kg over 28 weeks [113] and 9.5 kg over 45 weeks [63]; in comparison, patients on olanzapine increased 3.6 kg after 8 weeks [142] and 16.2 kg after 45 weeks [63]; and those on risperidone, 7.2 kg after 45 weeks [63].

Aripiprazole

Treatment with aripiprazole among children and adolescents is reported to have a lower incidence of weight gain than other SGA [48]. However, aripiprazole has been associated with significant weight gain in naturalistic [58], open-label [14, 38, 105] and doubled-blind controlled studies [53, 125, 135]. A prospective study among 96 children aged 4–9 has shown a significant increase (an average of 2.4 kg) in weight over 16 weeks [58]. In comparison with placebo, patients on aripiprazole showed a significantly greater weight gain after 6 weeks [60] and after 8 weeks [125, 135]; which may be a frequent reason for discontinuing treatment [105]. In contrast, other studies reported non-significant weight gain, such as an 6-week randomised placebo-controlled trial (an average of weight gain of 1.2 kg in the aripiprazole group vs. 0,72 kg in the placebo group) [151] and two 8-week open-label studies (an average of BMI increase of 0.86 kg/m2) [38]. In addition, a double-blind controlled trial involving 296 bipolar disorder patients on aripiprazole [59] showed that the average weight gain was not significantly different between those on a low dose of aripiprazole (10 mg/day), those on a high dose (30 mg/day) and subjects on placebo (0.82, 1.08 and 0.56 kg, respectively). BMI appeared not to influence the dose-adjusted aripiprazole serum concentration [12].

Ziprasidone

In addition to studies comparing ziprasidone with other SGAs, there are a few studies analysing weight gain induced by ziprasidone specifically. After 8 weeks of treatment, no significant weight gain has been observed in an open-label, uncontrolled study [13] and in two double-blind randomised studies [55, 139]. In a ziprasidone open-label trial consisting of a 3-week fixed-dose period (80–160 mg/day) and a subsequent 24-week flexible-dose period (20–160 mg/day) in patients aged 10–17 years, the mean weight gain was 1.0 ± 1.0 kg at week 3 (n = 61) and 2.8 ± 6.3 kg at week 27 (n = 47) [46].

Concomitant treatment

Exposure to two or more medications would appear to be a predictor of overweight or obesity, as seen in a large sample of bipolar disorder paediatric patients [75]. In particular, exposure to antipsychotic poly-pharmacotherapy may confer a higher risk of developing adverse events than monotherapy, especially for females [88]. In a cohort of 4,140 children and adolescents on antipsychotics [118], patients exposed to multiple antipsychotics were at a significantly higher risk for incident obesity or weight gain (OR = 2.28; 95 % CI = 1.43–3.65). On the other hand, two retrospective chart reviews of juvenile psychiatric inpatients exposed to risperidone during 6 months showed that weight gain was not influenced by the use of other non-antipsychotic psychotropic medications [93, 108]. Similarly, in another recent chart review study among children and adolescents, psychiatric outpatients treated with SGAs (risperidone, aripiprazole, olanzapine and quetiapine) had a zBMI significantly higher than psychiatric controls without lifetime SGA, and these differences remained after eliminating patients on any co-medication [41]. Other types of drugs, often used in children and adolescents, can have endocrine and metabolic adverse effects, including weight gain. Valproate, sometimes used together with antipsychotics, has been associated with weight gain [33]. In a bipolar disorder paediatric review [32], the authors observed that in trials lasting 12 weeks or less, weight gain was greater with SGAs plus mood stabilisers as compared to mood-stabiliser monotherapy or mood-stabiliser co-treatment, though compared with antipsychotic monotherapy the difference did not reach statistical significance. SGAs seemed to cause more weight gain than mood stabilisers in youth but not in adults [36, 72]. On the other hand, psychostimulants appeared to cause weight loss [29] and mild reversible growth retardation in some patients, most likely because of decreased weight or a slowing of expected weight gain [33]. However, psychostimulants in co-treatment with SGAs did not seem to attenuate SGA-induced weight gain [3].

BMI before antipsychotic treatment

Body mass index before antipsychotic treatment (pre-treatment or baseline BMI) may influence the development of antipsychotic-induced weight gain, especially in long-term treatments. One study which performed a systematic categorisation of the long-term (7.3 ± 9.2 years) weight course among adolescents and adults on clozapine, olanzapine and/or risperidone, showed that pre-treatment BMI had a predictive value on the antipsychotic-induced weight gain [70]. In particular, this study [70] found that increased values of patient’s BMI at premorbid stage or prior to antipsychotic treatment predicted higher body weight gain under antipsychotic treatment, but, on the other hand, a low BMI prior to first antipsychotic treatment predicted a higher speed of the total increase of BMI in vulnerable individuals.

When studies are restricted to children and adolescents, there are limited data on this issue. Available results suggest that patients with lower weight at onset show greater weight increase: it has been observed a significant negative correlation between baseline BMI and proportional weight gain [21, 128, 132], although other study could not find significant association between baseline BMI and weight gain after risperidone treatment [108].

Predisposing factors

Genetic factors

Antipsychotic-induced weight gain has been positively correlated with parental BMI among adults [70] and among children and adolescents [132]. In addition, twin studies based on monozygotic twin pairs and sib-pair studies suggested that antipsychotic-induced weight gain is more strongly under genetic than environmental control [71, 150]. Gebhardt et al. [71] found greater similarity in antipsychotic-induced BMI change in monozygotic twins than in same-sex sibs, with intra-class correlation coefficients of 0.87 and 0.56, respectively [71]. Following the set point theory [20], Thiesen et al. [150] hypothesised that antipsychotic effects on energy intake and expenditure might lead to a new energy balance, thus resulting in a ‘higher’ set point in patients ‘at risk’. Because weight gain is also associated with an increment in fat-free mass, which is the main determinant of energy expenditure, weight gain will be terminated (weight plateau) once a new energy balance is achieved [150]. Other studies in adults suggested an association between genetic factors (such as 5-HT2C receptor gene loci) and vulnerability to weight gain induced by antipsychotics [16, 134]. One of these studies [16] showed an association between serotonin transporter (SERT) gene and olanzapine-induced weight gain. In particular, the presence of the short (s) SERT promoter allelic variant and ss genotype was associated with significantly higher weight gain in subjects who were not obese at the time of admission [16]. The variant T allele of the −759C/T polymorphism in the promoter region of the HTR2C gene seemed to be protective against risperidone-induced weight gain [83], whereas the HTR2C p.C23S and CYP2D6 polymorphisms have been associated with risperidone-induced increase in BMI or waist circumference [28].

On the other hand, genes of several hormones may be related to greater antipsychotic-induced weight gain among children and adolescents. A recent study have shown a significant association between the melanocortin 4 receptor (MC4R) gene and extreme SGA-induced weight gain and related metabolic disturbances [104]. Moreover, the variant A allele of the −2548G/A polymorphism in the promoter region of the leptin gene has been associated with a lower risperidone-induced weight gain, [22] suggesting genetic differences in tissue sensitivity to leptin. Therefore, a possible mechanism of SGA-induced weight gain may be the desensitisation of leptin receptors so that the feedback from the adipocytes is not “heard” by the satiety centre [109]. In this way, high leptin levels reported in the literature in association with SGA exposure could be an effect rather than the cause of weight gain. In fact, serum leptin change did not reliably predict risperidone-associated weight gain [109]. Finally, antipsychotic-induced changes in BMI have been associated with six markers in the adiponectin gene among adult patients with schizophrenia [86]. Nevertheless, little is known regarding this topic among children and adolescents.

Socio-demographic factors

Female sex has been associated with a higher possibility of antipsychotic-induced weight gain [88, 118]. Contrariwise, in a study of 37 child and adolescent inpatients treated with risperidone for 6 consecutive months there was no difference in the risk of weight gain between both sexes [108]. Moreover, in a retrospective study [138], the largest increase in BMI was observed in males among patients on risperidone and in females among those on olanzapine. Meanwhile, the social and emotional consequences of weight gain in children and adolescents may be stronger in girls than in boys. A prospective study has demonstrated that women with metabolic syndrome in childhood have higher levels of depressive symptoms in adulthood than women free of childhood metabolic syndrome [130]. On the other hand, a cross-sectional study including 74 adolescents with schizophrenia on clozapine or olanzapine showed that an elevated BMI was associated with impaired physical functioning in females and with negative body appraisal and hunger in males [10].

Regarding age, it seems likely that youth, in comparison with adults, are more susceptible to adverse atypical antipsychotic metabolic side effects [30, 33, 34, 49, 63, 132, 137]. Children and adolescents appeared to be at higher risk than adults for antipsychotic-induced weight gain [33] and the risk of antipsychotic-induced weight gain among children might be higher in younger children [52]. Among patients with schizophrenia, children and adolescents appeared to be at higher risk for weight gain associated with antipsychotic treatment [26]. Specifically, olanzapine-treated adolescents experienced greater increases in body weight than olanzapine-treated adults [98, 132]. Risperidone and clozapine have similarly been associated with weight gain in adolescents, much higher than that reported in adults [63, 132].

African-American race has been associated with a lower risk for incident obesity/weight gain among children and adolescents on antipsychotics [118]. However, other authors [65] did not find differences across races.

Treatment of antipsychotic-induced BMI increase

In some cases of weight or BMI increase induced by antipsychotics, alternative treatment should be considered. The first option may be changing the antipsychotic drug or choosing a type of antipsychotic with a better benefit/risk ratio such as ziprasidone, which might be given as a first prescription in cases of higher BMI or higher vulnerability to increase BMI. Notwithstanding, antipsychotic-induced weight gain seems to differ depending on the particular drug presentation. Among adolescents, a cross-sectional study to compare the changes in weight and BMI associated with olanzapine orally disintegrating tablets, olanzapine standard oral tablets or risperidone, reported that those on olanzapine orally disintegrating tablets gained less weight than those on olanzapine standard oral tablets, but not less than those on risperidone [37]. However, among adults, the only randomised clinical trial comparing these two olanzapine formulations found no significant difference [92].

A second option could be to prescribe co-treatment with other drugs such as topiramate or metformin. Topiramate among children and adolescents has been associated with weight loss among those with bipolar disorder [32] and those with autistic spectrum disorders [24]. In an open-label trial involving paediatric patients with bipolar disorder [154], after 8 weeks of treatment, the main weight gain in the olanzapine group was 5.3 ± 2.1 kg and the weight gain in the olanzapine plus topiramate group was significantly lower, 2.6 ± 3.6 kg. In turn, metformin seemed to have a pronounced weight-reducing effect in antipsychotic-treated patients, especially in those with a manifest weight gain. A systematic review [15] showed that, compared with placebo, metformin treatment caused a significant body weight reduction in adult non-diabetic patients treated with atypical antipsychotics (4.8 %; 95 % CI = 1.6–8.0) and in children (4.1 %; 95 % CI = 2.2–6.0); when the analysis was restricted to patients with a manifest body weight increase (>10 %) prior to randomisation, metformin reduced weight by 7.5 % (95 % CI = 2.9–12.0); the effect was larger in Asians (7.8 %; 95 % CI = 4.4–11.2) than in Hispanics (2.0 %; 95 % CI = 0.7–3.3) [15]. A metformin double-blind controlled trial including children and adolescents who had gained more than 10 % of their pre-drug weight after treatment with olanzapine, risperidone or quetiapine, showed that while the placebo group continued to gain weight (mean = 4.01 ± 6.2 kg) over 16 weeks, the weight of the subjects treated with metformin showed little change over the treatment period (mean = −0.13 ± 2.8 kg) [96]. However, in another double-blind controlled trial [5], metformin treatment did not show a significant effect in controlling the BMI of children and adolescents with schizophrenia after 12 weeks.

Finally, lifestyle therapies and other non-pharmacological interventions have been shown to be effective in controlled clinical trials [26]. In some cases, alternative treatments such as repetitive trans-cranial magnetic stimulations may be required; their efficacy and their place in the therapeutic strategy of pharmaco-resistant schizophrenia in children and adolescents need to be assessed with regard to metabolic and blood side effects of clozapine [74].

Discussion

This is a comprehensive and descriptive review intended to highlight our knowledge about one of the most important issues for public health in conjunction with the use of antipsychotic medication. There is evidence that SGAs, in comparison with FGAs, are associated with a higher weight gain and increase of BMI. Within SGAs, olanzapine appears to cause the most significant weight gain, while ziprasidone seems to cause the least. The dose–response relationship between antipsychotic doses and degree of weight gain remains unclear. Antipsychotic-induced BMI increase tends to remain regardless of the specific psychotropic co-treatment. Children and adolescents would appear to be at a greater risk than adults for antipsychotic-induced weight gain; and the younger the child, the higher the risk. Genetic or environmental factors related to antipsychotic-induced weight gain among children and adolescents are mostly unknown. Certain genetic factors associated with antipsychotic-induced weight gain may be related to serotonin receptors or hormones such as leptin, adiponectin or melanocortin.

Several methodological limitations in studies of antipsychotic-induced weight gain or BMI increase must be underlined. An extended methodological limitation across many studies is not accounting for sex- and age-standardised BMI (zBMI, which is the best-suited measure to assess long-term drug-induced weight gain in comparison to developmental changes). Although the use of this methodology is crucial in medium-term and long-term studies of SGA-induced weight gain, few studies have used it so far [35]. Another frequent limitation in many studies is not taking into account the BMI before antipsychotic treatment. As it has been explained above (“BMI before antipsychotic treatment”), pre-treatment BMI may predict future antipsychotic-induced weight gain. Therefore, studies on antipsychotic-induced weight gain should include in their analyses the pre-treatment BMI, especially when they compare increase of BMI after treatment with different antipsychotic drugs.

Another possible bias when assessing antipsychotic-induced weight gain in observational studies is “confounding by indication,” meaning that physicians might be prone to prescribe a specific atypical antipsychotic drug according to the initial clinician’s impression about the patient’s weight. Clinicians may have different reasons for prescribing a specific antipsychotic drug, and one important reason may be the potential weight gain associated with each drug. This type of indication is opposed to randomisation and therefore might be confounding [110]. This was the case in a prospective study [51] investigating the factors influencing physicians’ choice of antipsychotic drug therapy in the treatment of adults with schizophrenia, where it was found that patients on amisulpride had a significantly higher previous BMI than patients on olanzapine. In a previous study [110], we conducted a 6-month follow-up of children and adolescents naïve to antipsychotic medication who were prescribed a SGA (aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine or risperidone), and we found that patients on olanzapine or quetiapine had an initial zBMI significantly lower than those on aripiprazole. The increase in zBMI at the end of the follow-up was significantly higher for patients on olanzapine than for the rest of the patients (4.0 vs. 1.1 kg/m2; p = 0.021). Nevertheless, the olanzapine effect became non-significant (p = 0.37) after adjusting by sex, age, baseline zBMI and the interaction between baseline zBMI and olanzapine treatment. Patients on olanzapine in our sample apparently showed a higher increase in their zBMI when compared to those on risperidone or aripiprazole, although confounding by indication may have exerted some influence and they might have gained weight more easily since their initial zBMI was lower [110]. Confounding by indication is the main bias of observational studies of treatment effects [77] and must be considered especially when evaluating antipsychotic effects. Most studies of weight gain among children and adolescents treated with atypical antipsychotics are observational and involve a short period of treatment [63].

Heterogeneity of diagnoses is very frequent among studies on antipsychotic-induced weight gain studies, including attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, autism, pervasive developmental disorder, disruptive behaviour, Tourette syndrome and psychotic, anxiety or affective disorders (Tables 1, 2, 3). Not only the antipsychotic treatment but also mental illness itself may be conducive to excessive weight gain among psychiatric patients, as these individuals are less likely to be active and more likely to have a poor dietary pattern than the general population, as has been shown in adults [17, 78]. Weight gain induced by antipsychotic treatment might present peculiarities within a specific diagnostic category; for instance, a literature review [40] showed that significant weight gain appears to be more prevalent in patients with autistic disorder who also were younger and probably less previously exposed to antipsychotics. Nevertheless, in a 3-month prospective longitudinal study of 90 children and adolescents treated with SGAs [119], weight gain and zBMI significantly increased in patients with bipolar disorder, other psychotic disorders or other non-psychotic disorders, but the differences between diagnostic groups did not reach statistical significance. Within patients with schizophrenia, psychopathology (e.g. food poisoning delusions), comorbidity with metabolic syndrome or psychoactive substance use disorder, and unhealthy lifestyle may influence BMI increase among children and adolescents taking antipsychotics. This point could be a line of future research.

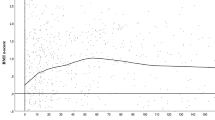

A short period of treatment is a feature of most studies on weight gain among children and adolescents treated with atypical antipsychotics. Several long-term studies show that the effect on weight gain becomes smaller over time, as shown by a case–control study among youths with Tourette syndrome comparing the effects on zBMI between patients treated with pimozide or risperidone and those without antipsychotic medication; in particular, the differences observed after 1 year disappeared in the second and third year of follow-up [42]. Nevertheless, an accumulative increase in weight or zBMI became patent over time [56, 152]. Although long-term studies may give a better perspective, a significant proportion of patients may discontinue their participation in the trial because of weight gain and, therefore, a selection bias may undermine the validity of longer follow-up analyses, as can be observed in a multi-centre trial analysing, among other variables, weight and BMI changed after both an acute 8-week phase and a 44-week extension [56]. Finally, most studies include a short number of subjects (Tables 1, 2, 3) which could lead to non-significant results, mostly due to a type-2 error.

Youth psychiatric patients on antipsychotic treatment constitute a group at high risk of developing weight gain and metabolic disturbances which may increase the morbidity and mortality of this population. Moreover, obesity is associated with worse outcomes in some psychiatric disorders such as bipolar disorder [89]. Clinicians should take adequate precautions and provide parents and guardians with nutritional information in a proactive manner [6], and monitoring height, weight and BMI should always be part of regular side effect and health monitoring in paediatric patients [35]. Clinicians should complete careful baseline assessments and perform dietary and lifestyle counselling when initiating antipsychotic treatment, and then proactively monitor for adverse effects to optimise physical as well as psychiatric outcomes [30]. A good collaboration between child/adolescent psychiatrists, general practitioners and paediatricians is essential to maximise overall outcomes and to reduce the likelihood of premature cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [40]. In addition, strategies to reduce this antipsychotic side effect include switching to medications that have a lower effect in weight gain, lowering the dosage of medications and initiating treatment with metformin or topiramate to address clinically relevant changes. In addition, some lifestyle therapies and other non-pharmacological interventions may be required.

Future studies should include long-term double-blind randomised trials and comparable data for more than two atypical antipsychotics to establish the real effects of each atypical antipsychotic in the increase of the zBMI. Designs of studies should include analysis of zBMI, and not just BMI, as well adjustment by baseline zBMI. In addition, future studies may be focused on several targets such as (1) to include and compare antipsychotic-induced weight gain across different psychiatric diagnoses to define the groups of patients at higher risk to develop weight gain or zBMI increase; (2) to compare, using large samples, SGAs that apparently cause less weight gain such as ziprasidone with those that apparently cause more weight gain such as olanzapine in long-term double-blind randomised trials; (3) to assess the dose–response effect between antipsychotic doses and the degree of zBMI increase; and (4) to determine genetic and environmental factors which may be confounding the association between a specific antipsychotic and increase of zBMI.

Antipsychotic-induced weight gain may be a complex matter in which numerous variables of a genetic, clinical, socio-demographic or environmental nature apparently intervene. Studies to determine and control for these possible confounding factors are needed to devise specific prevention programs.

References

Almandil NB, Wong IC (2011) Review on the current use of antipsychotic drugs in children and adolescents. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed 96:192–196

Aman MG, Arnold LE, McDougle CJ, Vitiello B, Scahill L, Davies M, McCracken JT, Tierney E, Nash PL, Posey DJ, Chuang S, Martin A, Shah B, Gonzalez NM, Swiezy NB, Ritz L, Koenig K, McGough J, Ghuman JK, Lindsay RL (2005) Acute and long-term safety and tolerability of risperidone in children with autism. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 15:869–884

Aman MG, Binder C, Turgay A (2004) Risperidone effects in the presence/absence of psychostimulant medicine in children with ADHD, other disruptive behavior disorders, and subaverage IQ. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 14:243–254

Arango C, Robles O, Parellada M, Fraguas D, Ruiz-Sancho A, Medina O, Zabala A, Bombin I, Moreno D (2009) Olanzapine compared to quetiapine in adolescents with a first psychotic episode. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 18:418–428

Arman S, Sadramely MR, Nadi M, Koleini N (2008) A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of metformin treatment for weight gain associated with initiation of risperidone in children and adolescents. Saudi Med J 29:1130–1134

Armenteros JL, Davies M (2006) Antipsychotics in early onset Schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 15:141–148

Armenteros JL, Lewis JE, Davalos M (2007) Risperidone augmentation for treatment-resistant aggression in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a placebo-controlled pilot study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 46:558–565

Armenteros JL, Whitaker AH, Welikson M, Stedge DJ, Gorman J (1997) Risperidone in adolescents with schizophrenia: an open pilot study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36:694–700

Arnold LE, Farmer C, Kraemer HC, Davies M, Witwer A, Chuang S, DiSilvestro R, McDougle CJ, McCracken J, Vitiello B, Aman MG, Scahill L, Posey DJ, Swiezy NB (2010) Moderators, mediators, and other predictors of risperidone response in children with autistic disorder and irritability. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 20:83–93

Bachmann CJ, Gebhardt S, Lehr D, Haberhausen M, Kaiser C, Otto B, Theisen FM (2012) Subjective and biological weight-related parameters in adolescents and young adults with schizophrenia spectrum disorder under clozapine or olanzapine treatment. Z Kinder Jugendpsychiatr Psychother 40:151–158 (quiz 158–159)

Bachmann CJ, Haberhausen M, Heinzel-Gutenbrunner M, Remschmidt H, Theisen FM (2008) Large intraindividual variability of olanzapine serum concentrations in adolescent patients. Ther Drug Monit 30:108–112

Bachmann CJ, Rieger-Gies A, Heinzel-Gutenbrunner M, Hiemke C, Remschmidt H, Theisen FM (2008) Large variability of aripiprazole and dehydroaripiprazole serum concentrations in adolescent patients with schizophrenia. Ther Drug Monit 30:462–466

Biederman J, Mick E, Spencer T, Dougherty M, Aleardi M, Wozniak J (2007) A prospective open-label treatment trial of ziprasidone monotherapy in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 9:888–894

Biederman J, Mick E, Spencer T, Doyle R, Joshi G, Hammerness P, Kotarski M, Aleardi M, Wozniak J (2007) An open-label trial of aripiprazole monotherapy in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. CNS Spectr 12:683–689

Björkhem-Bergman L, Asplund AB, Lindh JD (2011) Metformin for weight reduction in non-diabetic patients on antipsychotic drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychopharmacol 25:299–305

Bozina N, Medved V, Kuzman MR, Sain I, Sertic J (2007) Association study of olanzapine-induced weight gain and therapeutic response with SERT gene polymorphisms in female schizophrenic patients. J Psychopharmacol 21:728–734

Brown S, Birtwistle J, Roe L, Thompson C (1999) The unhealthy lifestyle of people with schizophrenia. Psychol Med 29:697–701

Buitelaar JK (2000) Open-label treatment with risperidone of 26 psychiatrically-hospitalized children and adolescents with mixed diagnoses and aggressive behavior. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 10:19–26

Buitelaar JK, van der Gaag RJ, Cohen-Kettenis P, Melman CT (2001) A randomized controlled trial of risperidone in the treatment of aggression in hospitalized adolescents with subaverage cognitive abilities. J Clin Psychiatry 62:239–248

Cabanac M, Duclaux R, Spector NH (1971) Sensory feedback in regulation of body weight: is there a ponderostat? Nature 229:125–127

Calarge CA, Acion L, Kuperman S, Tansey M, Schlechte JA (2009) Weight gain and metabolic abnormalities during extended risperidone treatment in children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 19:101–109

Calarge CA, Ellingrod VL, Zimmerman B, Acion L, Sivitz WI, Schlechte JA (2009) Leptin gene -2548G/A variants predict risperidone-associated weight gain in children and adolescents. Psychiatr Genet 19:320–327

Calarge CA, del Miller D (2011) Predictors of risperidone and 9-hydroxyrisperidone serum concentration in children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 21:163–169

Canitano R (2005) Clinical experience with Topiramate to counteract neuroleptic induced weight gain in 10 individuals with autistic spectrum disorders. Brain Dev 27:228–232

Castro-Fornieles J, Parellada M, Soutullo CA, Baeza I, Gonzalez-Pinto A, Graell M, Paya B, Moreno D, de la Serna E, Arango C (2008) Antipsychotic treatment in child and adolescent first-episode psychosis: a longitudinal naturalistic approach. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 18:327–336

Citrome L, Vreeland B (2008) Schizophrenia, obesity, and antipsychotic medications: what can we do? Postgrad Med 120:18–33

Cohen D, Bonnot O, Bodeau N, Consoli A, Laurent C (2012) Adverse effects of second-generation antipsychotics in children and adolescents: a Bayesian meta-analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol 32:309–316

Correia CT, Almeida JP, Santos PE, Sequeira AF, Marques CE, Miguel TS, Abreu RL, Oliveira GG, Vicente AM (2010) Pharmacogenetics of risperidone therapy in autism: association analysis of eight candidate genes with drug efficacy and adverse drug reactions. Pharmacogenomics J 10:418–430

Correia FAG, Bodanese R, Silva TL, Alvares JP, Aman M, Rohde LA (2005) Comparison of risperidone and methylphenidate for reducing ADHD symptoms in children and adolescents with moderate mental retardation. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 44:748–755

Correll CU (2011) Addressing adverse effects of antipsychotic treatment in young patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 72:e01

Correll CU (2005) Metabolic side effects of second-generation antipsychotics in children and adolescents: a different story? J Clin Psychiatry 66:1331–1332

Correll CU (2007) Weight gain and metabolic effects of mood stabilizers and antipsychotics in pediatric bipolar disorder: a systematic review and pooled analysis of short-term trials. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 46:687–700

Correll CU, Carlson HE (2006) Endocrine and metabolic adverse effects of psychotropic medications in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 45:771–791

Correll CU, Manu P, Olshanskiy V, Napolitano B, Kane JM, Malhotra AK (2009) Cardiometabolic risk of second-generation antipsychotic medications during first-time use in children and adolescents. JAMA 302:1765–1773

Correll CU, Penzner JB, Parikh UH, Mughal T, Javed T, Carbon M, Malhotra AK (2006) Recognizing and monitoring adverse events of second-generation antipsychotics in children and adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 15:177–206

Correll CU, Sheridan EM, DelBello MP (2010) Antipsychotic and mood stabilizer efficacy and tolerability in pediatric and adult patients with bipolar I mania: a comparative analysis of acute, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Bipolar Disord 12:116–141

Crocq MA, Guillon MS, Bailey PE, Provost D (2007) Orally disintegrating olanzapine induces less weight gain in adolescents than standard oral tablets. Eur Psychiatry 22:453–454

Cui YH, Zheng Y, Yang YP, Liu J, Li J (2010) Effectiveness and tolerability of aripiprazole in children and adolescents with Tourette’s disorder: a pilot study in China. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 20:291–298

Cheng-Shannon J, McGough JJ, Pataki C, McCracken JT (2004) Second-generation antipsychotic medications in children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 14:372–394

De Hert M, Dobbelaere M, Sheridan EM, Cohen D, Correll CU (2011) Metabolic and endocrine adverse effects of second-generation antipsychotics in children and adolescents: a systematic review of randomized, placebo controlled trials and guidelines for clinical practice. Eur Psychiatry 26:144–158

de Hoogd S, Overbeek WA, Heerdink ER, Correll CU, de Graeff ER, Staal WG (2012) Differences in body mass index z-scores and weight status in a Dutch pediatric psychiatric population with and without use of second-generation antipsychotics. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 22:166–173

Degrauw RS, Li JZ, Gilbert DL (2009) Body mass index changes and chronic neuroleptic drug treatment for Tourette syndrome. Pediatr Neurol 41:183–186

DelBello MP, Adler CM, Whitsel RM, Stanford KE, Strakowski SM (2007) A 12-week single-blind trial of quetiapine for the treatment of mood symptoms in adolescents at high risk for developing bipolar I disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 68:789–795

DelBello MP, Chang K, Welge JA, Adler CM, Rana M, Howe M, Bryan H, Vogel D, Sampang S, Delgado SV, Sorter M, Strakowski SM (2009) A double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of quetiapine for depressed adolescents with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 11:483–493

DelBello MP, Kowatch RA, Adler CM, Stanford KE, Welge JA, Barzman DH, Nelson E, Strakowski SM (2006) A double-blind randomized pilot study comparing quetiapine and divalproex for adolescent mania. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 45:305–313

DelBello MP, Versavel M, Ice K, Keller D, Miceli J (2008) Tolerability of oral ziprasidone in children and adolescents with bipolar mania, schizophrenia, or schizoaffective disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 18:491–499

Dittmann RW, Meyer E, Freisleder FJ, Remschmidt H, Mehler-Wex C, Junghanss J, Hagenah U, Schulte-Markwort M, Poustka F, Schmidt MH, Schulz E, Mastele A, Wehmeier PM (2008) Effectiveness and tolerability of olanzapine in the treatment of adolescents with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders: results from a large, prospective, open-label study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 18:54–69

Doey T (2012) Aripiprazole in pediatric psychosis and bipolar disorder: a clinical review. J Affect Disord 138(Suppl):S15–S21

Dori N, Green T (2011) The metabolic syndrome and antipsychotics in children and adolescents. Harefuah 150:791–796, 814, 813

Eapen V, John G (2011) Weight gain and metabolic syndrome among young patients on antipsychotic medication: what do we know and where do we go? Australas Psychiatry 19:232–235

Edlinger M, Hofer A, Rettenbacher MA, Baumgartner S, Widschwendter CG, Kemmler G, Neco NA, Fleischhacker WW (2009) Factors influencing the choice of new generation antipsychotic medication in the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 113:246–251

Fedorowicz VJ, Fombonne E (2005) Metabolic side effects of atypical antipsychotics in children: a literature review. J Psychopharmacol 19:533–550

Findling RL (2008) Atypical antipsychotic treatment of disruptive behavior disorders in children and adolescents. J Clin Psychiatry 69(Suppl 4):9–14

Findling RL, Aman MG, Eerdekens M, Derivan A, Lyons B (2004) Long-term, open-label study of risperidone in children with severe disruptive behaviors and below-average IQ. Am J Psychiatry 161:677–684

Findling RL, Cavus I, Pappadolulos E, Backinsky M, Schwartz JH, Vanderburg DG (2010) A placebo-controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of flexibly dosed oral ziprasidone in adolescent subjects with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 117:437

Findling RL, Johnson JL, McClellan J, Frazier JA, Vitiello B, Hamer RM, Lieberman JA, Ritz L, McNamara NK, Lingler J, Hlastala S, Pierson L, Puglia M, Maloney AE, Kaufman EM, Noyes N, Sikich L (2010) Double-blind maintenance safety and effectiveness findings from the Treatment of Early-Onset Schizophrenia Spectrum (TEOSS) study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 49:583–594 (quiz 632)

Findling RL, McNamara NK, Branicky LA, Schluchter MD, Lemon E, Blumer JL (2000) A double-blind pilot study of risperidone in the treatment of conduct disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 39:509–516

Findling RL, McNamara NK, Youngstrom EA, Stansbrey RJ, Frazier TW, Lingler J, Otto BD, Demeter CA, Rowles BM, Calabrese JR (2011) An open-label study of aripiprazole in children with a bipolar disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 21:345–351

Findling RL, Nyilas M, Forbes RA, McQuade RD, Jin N, Iwamoto T, Ivanova S, Carson WH, Chang K (2009) Acute treatment of pediatric bipolar I disorder, manic or mixed episode, with aripiprazole: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry 70:1441–1451

Findling RL, Robb A, Nyilas M, Forbes RA, Jin N, Ivanova S, Marcus R, McQuade RD, Iwamoto T, Carson WH (2008) A multiple-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of oral aripiprazole for treatment of adolescents with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 165:1432–1441

Fleischhaker C, Heiser P, Hennighausen K, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Holtkamp K, Mehler-Wex C, Rauh R, Remschmidt H, Schulz E, Warnke A (2006) Clinical drug monitoring in child and adolescent psychiatry: side effects of atypical neuroleptics. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 16:308–316

Fleischhaker C, Heiser P, Hennighausen K, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Holtkamp K, Mehler-Wex C, Rauh R, Remschmidt H, Schulz E, Warnke A (2007) Weight gain associated with clozapine, olanzapine and risperidone in children and adolescents. J Neural Transm 114:273–280

Fleischhaker C, Heiser P, Hennighausen K, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Holtkamp K, Mehler-Wex C, Rauh R, Remschmidt H, Schulz E, Warnke A (2008) Weight gain in children and adolescents during 45 weeks treatment with clozapine, olanzapine and risperidone. J Neural Transm 115:1599–1608

Fraguas D, Correll CU, Merchan-Naranjo J, Rapado-Castro M, Parellada M, Moreno C, Arango C (2011) Efficacy and safety of second-generation antipsychotics in children and adolescents with psychotic and bipolar spectrum disorders: comprehensive review of prospective head-to-head and placebo-controlled comparisons. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 21:621–645

Fraguas D, Merchan-Naranjo J, Laita P, Parellada M, Moreno D, Ruiz-Sancho A, Cifuentes A, Giraldez M, Arango C (2008) Metabolic and hormonal side effects in children and adolescents treated with second-generation antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry 69:1166–1175

Frazier JA, Biederman J, Tohen M, Feldman PD, Jacobs TG, Toma V, Rater MA, Tarazi RA, Kim GS, Garfield SB, Sohma M, Gonzalez-Heydrich J, Risser RC, Nowlin ZM (2001) A prospective open-label treatment trial of olanzapine monotherapy in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 11:239–250

Frazier JA, Meyer MC, Biederman J, Wozniak J, Wilens TE, Spencer TJ, Kim GS, Shapiro S (1999) Risperidone treatment for juvenile bipolar disorder: a retrospective chart review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 38:960–965

Frémaux T, Reymann JM, Chevreuil C, Bentue-Ferrer D (2007) Prescription of olanzapine in children and adolescent psychiatric patients. Encephale 33:188–196

Gagliano A, Germano E, Pustorino G, Impallomeni C, D’Arrigo C, Calamoneri F, Spina E (2004) Risperidone treatment of children with autistic disorder: effectiveness, tolerability, and pharmacokinetic implications. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 14:39–47

Gebhardt S, Haberhausen M, Heinzel-Gutenbrunner M, Gebhardt N, Remschmidt H, Krieg JC, Hebebrand J, Theisen FM (2009) Antipsychotic-induced body weight gain: predictors and a systematic categorization of the long-term weight course. J Psychiatr Res 43:620–626

Gebhardt S, Theisen FM, Haberhausen M, Heinzel-Gutenbrunner M, Wehmeier PM, Krieg JC, Kuhnau W, Schmidtke J, Remschmidt H, Hebebrand J (2010) Body weight gain induced by atypical antipsychotics: an extension of the monozygotic twin and sib pair study. J Clin Pharm Ther 35:207–211

Geller B, Luby JL, Joshi P, Wagner KD, Emslie G, Walkup JT, Axelson DA, Bolhofner K, Robb A, Wolf DV, Riddle MA, Birmaher B, Nusrat N, Ryan ND, Vitiello B, Tillman R, Lavori P (2012) A randomized controlled trial of risperidone, lithium, or divalproex sodium for initial treatment of bipolar I disorder, manic or mixed phase, in children and adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry 69:515–528

Gencer O, Emiroglu FN, Miral S, Baykara B, Baykara A, Dirik E (2008) Comparison of long-term efficacy and safety of risperidone and haloperidol in children and adolescents with autistic disorder. An open label maintenance study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 17:217–225

Goeb JL, Marco S, Duhamel A, Kechid G, Bordet R, Thomas P, Delion P, Jardri R (2010) Metabolic side effects of risperidone in early onset schizophrenia. Encephale 36:242–252

Goldstein BI, Birmaher B, Axelson DA, Goldstein TR, Esposito-Smythers C, Strober MA, Hunt J, Leonard H, Gill MK, Iyengar S, Grimm C, Yang M, Ryan ND, Keller MB (2008) Preliminary findings regarding overweight and obesity in pediatric bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 69:1953–1959

Gothelf D, Falk B, Singer P, Kairi M, Phillip M, Zigel L, Poraz I, Frishman S, Constantini N, Zalsman G, Weizman A, Apter A (2002) Weight gain associated with increased food intake and low habitual activity levels in male adolescent schizophrenic inpatients treated with olanzapine. Am J Psychiatry 159:1055–1057

Green SB, Byar DP (1984) Using observational data from registries to compare treatments: the fallacy of omnimetrics. Stat Med 3:361–373

Gurpegui M, Martinez-Ortega JM, Gutierrez-Rojas L, Rivero J, Rojas C, Jurado D (2012) Overweight and obesity in patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia compared with a non-psychiatric sample. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 37:169–175

Haas M, Delbello MP, Pandina G, Kushner S, Van Hove I, Augustyns I, Quiroz J, Kusumakar V (2009) Risperidone for the treatment of acute mania in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Bipolar Disord 11:687–700

Haas M, Eerdekens M, Kushner S, Singer J, Augustyns I, Quiroz J, Pandina G, Kusumakar V (2009) Efficacy, safety and tolerability of two dosing regimens in adolescent schizophrenia: double-blind study. Br J Psychiatry 194:158–164

Haas M, Karcher K, Pandina GJ (2008) Treating disruptive behavior disorders with risperidone: a 1-year, open-label safety study in children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 18:337–345

Handen BL, Hardan AY (2006) Open-label, prospective trial of olanzapine in adolescents with subaverage intelligence and disruptive behavioral disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 45:928–935

Hoekstra PJ, Troost PW, Lahuis BE, Mulder H, Mulder EJ, Franke B, Buitelaar JK, Anderson GM, Scahill L, Minderaa RB (2010) Risperidone-induced weight gain in referred children with autism spectrum disorders is associated with a common polymorphism in the 5-hydroxytryptamine 2C receptor gene. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 20:473–477

Hollander E, Wasserman S, Swanson EN, Chaplin W, Schapiro ML, Zagursky K, Novotny S (2006) A double-blind placebo-controlled pilot study of olanzapine in childhood/adolescent pervasive developmental disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 16:541–548

Hrdlicka M, Zedkova I, Blatny M, Urbanek T (2009) Weight gain associated with atypical and typical antipsychotics during treatment of adolescent schizophrenic psychoses: a retrospective study. Neuro Endocrinol Lett 30:256–261

Jassim G, Ferno J, Theisen FM, Haberhausen M, Christoforou A, Havik B, Gebhardt S, Remschmidt H, Mehler-Wex C, Hebebrand J, Lehellard S, Steen VM (2011) Association study of energy homeostasis genes and antipsychotic-induced weight gain in patients with schizophrenia. Pharmacopsychiatry 44:15–20

Jensen JB, Kumra S, Leitten W, Oberstar J, Anjum A, White T, Wozniak J, Lee SS, Schulz SC (2008) A comparative pilot study of second-generation antipsychotics in children and adolescents with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 18:317–326

Jerrell JM, McIntyre RS (2008) Adverse events in children and adolescents treated with antipsychotic medications. Hum Psychopharmacol 23:283–290

Jolin EM, Weller EB, Weller RA (2007) The public health aspects of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. Curr Psychiatry Rep 9:106–113

Joshi G, Petty C, Wozniak J, Faraone SV, Doyle R, Georgiopoulos A, Hammerness P, Walls S, Glaeser B, Brethel K, Yorks D, Biederman J (2012) A prospective open-label trial of quetiapine monotherapy in preschool and school age children with bipolar spectrum disorder. J Affect Disord 136:1143–1153

Kapetanovic S, Aaron L, Montepiedra G, Sirois PA, Oleske JM, Malee K, Pearson DA, Nichols SL, Garvie PA, Farley J, Nozyce ML, Mintz M, Williams PL (2009) The use of second-generation antipsychotics and the changes in physical growth in children and adolescents with perinatally acquired HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS 23:939–947

Karagianis J, Grossman L, Landry J, Reed VA, de Haan L, Maguire GA, Hoffmann VP, Milev R (2009) A randomized controlled trial of the effect of sublingual orally disintegrating olanzapine versus oral olanzapine on body mass index: the PLATYPUS Study. Schizophr Res 113:41–48

Kelly DL, Conley RR, Love RC, Horn DS, Ushchak CM (1998) Weight gain in adolescents treated with risperidone and conventional antipsychotics over six months. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 8:151–159

Kemner C, Willemsen-Swinkels SH, de Jonge M, Tuynman-Qua H, van Engeland H (2002) Open-label study of olanzapine in children with pervasive developmental disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 22:455–460

Khan RA, Mican LM, Suehs BT (2009) Effects of olanzapine and risperidone on metabolic factors in children and adolescents: a retrospective evaluation. J Psychiatr Pract 15:320–328

Klein DJ, Cottingham EM, Sorter M, Barton BA, Morrison JA (2006) A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of metformin treatment of weight gain associated with initiation of atypical antipsychotic therapy in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry 163:2072–2079

Kryzhanovskaya L, Schulz SC, McDougle C, Frazier J, Dittmann R, Robertson-Plouch C, Bauer T, Xu W, Wang W, Carlson J, Tohen M (2009) Olanzapine versus placebo in adolescents with schizophrenia: a 6-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 48:60–70

Kryzhanovskaya LA, Robertson-Plouch CK, Xu W, Carlson JL, Merida KM, Dittmann RW (2009) The safety of olanzapine in adolescents with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder: a pooled analysis of 4 clinical trials. J Clin Psychiatry 70:247–258

Kryzhanovskaya LA, Xu W, Millen BA, Acharya N, Jen KY, Osuntokun O (2012) Comparison of long-term (at least 24 weeks) weight gain and metabolic changes between adolescents and adults treated with olanzapine. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 22:157–165

Kumra S, Kranzler H, Gerbino-Rosen G, Kester HM, De Thomas C, Kafantaris V, Correll CU, Kane JM (2008) Clozapine and “high-dose” olanzapine in refractory early-onset schizophrenia: a 12-week randomized and double-blind comparison. Biol Psychiatry 63:524–529

Lindsay RL, Leone S, Aman MG (2004) Discontinuation of risperidone and reversibility of weight gain in children with disruptive behavior disorders. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 43:437–444

Luby J, Mrakotsky C, Stalets MM, Belden A, Heffelfinger A, Williams M, Spitznagel E (2006) Risperidone in preschool children with autistic spectrum disorders: an investigation of safety and efficacy. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 16:575–587

Maayan L, Correll CU (2011) Weight gain and metabolic risks associated with antipsychotic medications in children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 21:517–535

Malhotra AK, Correll CU, Chowdhury NI, Muller DJ, Gregersen PK, Lee AT, Tiwari AK, Kane JM, Fleischhacker WW, Kahn RS, Ophoff RA, Meltzer HY, Lencz T, Kennedy JL (2012) Association between common variants near the melanocortin 4 receptor gene and severe antipsychotic drug-induced weight gain. Arch Gen Psychiatry 69:904–912

Marcus RN, Owen R, Manos G, Mankoski R, Kamen L, McQuade RD, Carson WH, Findling RL (2011) Safety and tolerability of aripiprazole for irritability in pediatric patients with autistic disorder: a 52-week, open-label, multicenter study. J Clin Psychiatry 72:1270–1276

Martin A, Koenig K, Scahill L, Bregman J (1999) Open-label quetiapine in the treatment of children and adolescents with autistic disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 9:99–107

Martin A, L’Ecuyer S (2002) Triglyceride, cholesterol and weight changes among risperidone-treated youths. A retrospective study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 11:129–133

Martin A, Landau J, Leebens P, Ulizio K, Cicchetti D, Scahill L, Leckman JF (2000) Risperidone-associated weight gain in children and adolescents: a retrospective chart review. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 10:259–268

Martin A, Scahill L, Anderson GM, Aman M, Arnold LE, McCracken J, McDougle CJ, Tierney E, Chuang S, Vitiello B (2004) Weight and leptin changes among risperidone-treated youths with autism: 6-month prospective data. Am J Psychiatry 161:1125–1127

Martinez-Ortega JM, Diaz-Atienza F, Gutierrez-Rojas L, Jurado D, Gurpegui M (2011) Confounding by indication of a specific antipsychotic and the increase of body mass index among children and adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 20:597–598

Masi G, Cosenza A, Mucci M, Brovedani P (2001) Open trial of risperidone in 24 young children with pervasive developmental disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 40:1206–1214

Masi G, Milone A, Canepa G, Millepiedi S, Mucci M, Muratori F (2006) Olanzapine treatment in adolescents with severe conduct disorder. Eur Psychiatry 21:51–57

Masi G, Mucci M, Millepiedi S (2002) Clozapine in adolescent inpatients with acute mania. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 12:93–99

McConville B, Carrero L, Sweitzer D, Potter L, Chaney R, Foster K, Sorter M, Friedman L, Browne K (2003) Long-term safety, tolerability, and clinical efficacy of quetiapine in adolescents: an open-label extension trial. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 13:75–82

McCracken JT, McGough J, Shah B, Cronin P, Hong D, Aman MG, Arnold LE, Lindsay R, Nash P, Hollway J, McDougle CJ, Posey D, Swiezy N, Kohn A, Scahill L, Martin A, Koenig K, Volkmar F, Carroll D, Lancor A, Tierney E, Ghuman J, Gonzalez NM, Grados M, Vitiello B, Ritz L, Davies M, Robinson J, McMahon D (2002) Risperidone in children with autism and serious behavioral problems. N Engl J Med 347:314–321

McCracken JT, Suddath R, Chang S, Thakur S, Piacentini J (2008) Effectiveness and tolerability of open label olanzapine in children and adolescents with Tourette syndrome. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 18:501–508

McDougle CJ, Holmes JP, Bronson MR, Anderson GM, Volkmar FR, Price LH, Cohen DJ (1997) Risperidone treatment of children and adolescents with pervasive developmental disorders: a prospective open-label study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36:685–693

McIntyre RS, Jerrell JM (2008) Metabolic and cardiovascular adverse events associated with antipsychotic treatment in children and adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 162:929–935

Moreno C, Merchan-Naranjo J, Alvarez M, Baeza I, Alda JA, Martinez-Cantarero C, Parellada M, Sanchez B, de la Serna E, Giraldez M, Arango C (2010) Metabolic effects of second-generation antipsychotics in bipolar youth: comparison with other psychotic and nonpsychotic diagnoses. Bipolar Disord 12:172–184

Mozes T, Ebert T, Michal SE, Spivak B, Weizman A (2006) An open-label randomized comparison of olanzapine versus risperidone in the treatment of childhood-onset schizophrenia. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 16:393–403

Mozes T, Greenberg Y, Spivak B, Tyano S, Weizman A, Mester R (2003) Olanzapine treatment in chronic drug-resistant childhood-onset schizophrenia: an open-label study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 13:311–317

Mukaddes NM, Abali O, Gurkan K (2004) Short-term efficacy and safety of risperidone in young children with autistic disorder (AD). World J Biol Psychiatry 5:211–214

Nagaraj R, Singhi P, Malhi P (2006) Risperidone in children with autism: randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. J Child Neurol 21:450–455

Nicolson R, Awad G, Sloman L (1998) An open trial of risperidone in young autistic children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 37:372–376

Owen R, Sikich L, Marcus RN, Corey-Lisle P, Manos G, McQuade RD, Carson WH, Findling RL (2009) Aripiprazole in the treatment of irritability in children and adolescents with autistic disorder. Pediatrics 124:1533–1540

Panagiotopoulos C, Ronsley R, Davidson J (2009) Increased prevalence of obesity and glucose intolerance in youth treated with second-generation antipsychotic medications. Can J Psychiatry 54:743–749

Patel NC, Hariparsad M, Matias-Akthar M, Sorter MT, Barzman DH, Morrison JA, Stanford KE, Strakowski SM, DelBello MP (2007) Body mass indexes and lipid profiles in hospitalized children and adolescents exposed to atypical antipsychotics. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 17:303–311

Patel NC, Kistler JS, James EB, Crismon ML (2004) A retrospective analysis of the short-term effects of olanzapine and quetiapine on weight and body mass index in children and adolescents. Pharmacotherapy 24:824–830

Pringsheim T, Lam D, Ching H, Patten S (2011) Metabolic and neurological complications of second-generation antipsychotic use in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Drug Saf 34:651–668

Pulkki-Raback L, Elovainio M, Kivimaki M, Mattsson N, Raitakari OT, Puttonen S, Marniemi J, Viikari JS, Keltikangas-Jarvinen L (2009) Depressive symptoms and the metabolic syndrome in childhood and adulthood: a prospective cohort study. Health Psychol 28:108–116

Quintana H, Wilson MS 2nd, Purnell W, Layman AK, Mercante D (2007) An open-label study of olanzapine in children and adolescents with schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Pract 13:86–96

Ratzoni G, Gothelf D, Brand-Gothelf A, Reidman J, Kikinzon L, Gal G, Phillip M, Apter A, Weizman R (2002) Weight gain associated with olanzapine and risperidone in adolescent patients: a comparative prospective study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 41:337–343

Reyes M, Olah R, Csaba K, Augustyns I, Eerdekens M (2006) Long-term safety and efficacy of risperidone in children with disruptive behaviour disorders. Results of a 2-year extension study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 15:97–104

Reynolds GP, Zhang ZJ, Zhang XB (2002) Association of antipsychotic drug-induced weight gain with a 5-HT2C receptor gene polymorphism. Lancet 359:2086–2087

Robb AS, Andersson C, Bellocchio EE, Manos G, Rojas-Fernandez C, Mathew S, Marcus R, Owen R, Mankoski R (2011) Safety and tolerability of aripiprazole in the treatment of irritability associated with autistic disorder in pediatric subjects (6-17 years old): results from a pooled analysis of 2 studies. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 13

Ross RG, Novins D, Farley GK, Adler LE (2003) A 1-year open-label trial of olanzapine in school-age children with schizophrenia. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 13:301–309

Safer DJ (2004) A comparison of risperidone-induced weight gain across the age span. J Clin Psychopharmacol 24:429–436

Saklad SR, Ketchi CM, Amrung SA (2002) Gender differences in weight gain among adolescents started on atypical antipsychotics. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 12:288–289

Sallee FR, Kurlan R, Goetz CG, Singer H, Scahill L, Law G, Dittman VM, Chappell PB (2000) Ziprasidone treatment of children and adolescents with Tourette’s syndrome: a pilot study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 39:292–299

Schimmelmann BG, Mehler-Wex C, Lambert M, Schulze-zur-Wiesch C, Koch E, Flechtner HH, Gierow B, Maier J, Meyer E, Schulte-Markwort M (2007) A prospective 12-week study of quetiapine in adolescents with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 17:768–778

Shaw JA, Lewis JE, Pascal S, Sharma RK, Rodriguez RA, Guillen R, Pupo-Guillen M (2001) A study of quetiapine: efficacy and tolerability in psychotic adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 11:415–424

Shaw P, Sporn A, Gogtay N, Overman GP, Greenstein D, Gochman P, Tossell JW, Lenane M, Rapoport JL (2006) Childhood-onset schizophrenia: a double-blind, randomized clozapine-olanzapine comparison. Arch Gen Psychiatry 63:721–730

Shea S, Turgay A, Carroll A, Schulz M, Orlik H, Smith I, Dunbar F (2004) Risperidone in the treatment of disruptive behavioral symptoms in children with autistic and other pervasive developmental disorders. Pediatrics 114:e634–e641

Sholevar EH, Baron DA, Hardie TL (2000) Treatment of childhood-onset schizophrenia with olanzapine. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 10:69–78

Sikich L, Frazier JA, McClellan J, Findling RL, Vitiello B, Ritz L, Ambler D, Puglia M, Maloney AE, Michael E, De Jong S, Slifka K, Noyes N, Hlastala S, Pierson L, McNamara NK, Delporto-Bedoya D, Anderson R, Hamer RM, Lieberman JA (2008) Double-blind comparison of first- and second-generation antipsychotics in early-onset schizophrenia and schizo-affective disorder: findings from the treatment of early-onset schizophrenia spectrum disorders (TEOSS) study. Am J Psychiatry 165:1420–1431

Sikich L, Hamer RM, Bashford RA, Sheitman BB, Lieberman JA (2004) A pilot study of risperidone, olanzapine, and haloperidol in psychotic youth: a double-blind, randomized, 8-week trial. Neuropsychopharmacology 29:133–145

Snyder R, Turgay A, Aman M, Binder C, Fisman S, Carroll A (2002) Effects of risperidone on conduct and disruptive behavior disorders in children with subaverage IQs. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 41:1026–1036

Swadi HS, Craig BJ, Pirwani NZ, Black VC, Buchan JC, Bobier CM (2010) A trial of quetiapine compared with risperidone in the treatment of first onset psychosis among 15- to 18-year-old adolescents. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 25:1–6

Szigethy E, Wiznitzer M, Branicky LA, Maxwell K, Findling RL (1999) Risperidone-induced hepatotoxicity in children and adolescents? A chart review study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 9:93–98

Theisen FM, Gebhardt S, Haberhausen M, Heinzel-Gutenbrunner M, Wehmeier PM, Krieg JC, Kuhnau W, Schmidtke J, Remschmidt H, Hebebrand J (2005) Clozapine-induced weight gain: a study in monozygotic twins and same-sex sib pairs. Psychiatr Genet 15:285–289

Tramontina S, Zeni CP, Ketzer CR, Pheula GF, Narvaez J, Rohde LA (2009) Aripiprazole in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder comorbid with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a pilot randomized clinical trial. J Clin Psychiatry 70:756–764

Turgay A, Binder C, Snyder R, Fisman S (2002) Long-term safety and efficacy of risperidone for the treatment of disruptive behavior disorders in children with subaverage IQs. Pediatrics 110:e34

Van Bellinghen M, De Troch C (2001) Risperidone in the treatment of behavioral disturbances in children and adolescents with borderline intellectual functioning: a double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 11:5–13

Wozniak J, Mick E, Waxmonsky J, Kotarski M, Hantsoo L, Biederman J (2009) Comparison of open-label, 8-week trials of olanzapine monotherapy and topiramate augmentation of olanzapine for the treatment of pediatric bipolar disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 19:539–545

Zuddas A, Di Martino A, Muglia P, Cianchetti C (2000) Long-term risperidone for pervasive developmental disorder: efficacy, tolerability, and discontinuation. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 10:79–90

Conflict of interest

The authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Martínez-Ortega, J.M., Funes-Godoy, S., Díaz-Atienza, F. et al. Weight gain and increase of body mass index among children and adolescents treated with antipsychotics: a critical review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 22, 457–479 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-013-0399-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-013-0399-5