Abstract

Background

The concept of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) involves the respondents’ perception of well-being and functioning in physical, emotional, mental, social, and everyday life areas. Research in the area of subjective health has resulted in the development of a multitude of HRQoL instruments that meet satisfying psychometric standards with regard to reliability, validity, and sensitivity of the scales. One frequently used generic measure for children and adolescents is the KINDL-R questionnaire developed by Ravens-Sieberer and Bullinger (Qual Life Res 7:399–407, 1998).

Methods

Within the representative sample of the BELLA study, analyses regarding psychometric properties (namely reliability as well as discriminant and construct validity) are performed.

Results

Psychometric testing of the KINDL-R questionnaire reveals good scale utilisation and scale fit as well as moderate internal consistency. Correlations with the KIDSCREEN-52 subscales are shown. Differences in KINDL-R scores exist between chronically ill and healthy children as well as between SDQ problem scores.

Conclusion

The KINDL-R is a suitable instrument for measuring HRQoL in children and adolescents through self-report. The testing of the instrument in a representative sample of German children and adolescents as well as their parents provides reference values extending the potential of the KINDL-R questionnaire.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is a multidimensional construct referring to the subjective perception of physical, mental, social, psychological, and functional aspects of well-being and health [5, 6, 22, 29]. Over the last 30 years, health-related quality of life research, both in adults as well as in children, has continuously increased. A literature search for “quality of life” in the PubMed database shows 95,480 publications, including 21,693 articles on children’s quality of life. Quality of life assessment is of special importance in epidemiological, clinical, and health economic settings. From an epidemiological point of view, information on quality of life is important to define health problems and to evaluate the well-being and functioning of populations. The patient’s subjective perception of well-being and health has become a relevant endpoint in addition to clinical data (such as the reduction of symptoms and mortality), especially when considering the increasing prevalence of chronic diseases. Health economic studies as well as cost and benefit analyses of treatments use HRQoL as a major criterion in the evaluation of prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation programs. Furthermore, the International Classification of Functioning (ICF) acknowledges the impact of chronic conditions on the patient, including social and psychological perspectives [7].

Various measures of quality of life in children and adolescents have been developed over the last several years [4, 23, 28]. Instruments can be subdivided into generic and disease-specific, or targeted, instruments. While generic instruments focus on describing the children’s health independent of the medical condition, disease-specific scales aim at analysing the health-related quality of life of chronically ill children. One major question is whether children are capable of reflecting on and reporting their feelings concerning health and well-being and, if so, at what age. For this reason, there are parent, or proxy, versions as well as self-report questionnaires available. In younger children, it is often necessary to ask parents to respond on behalf of their children; however, the degree of agreement between the child- and parent-report varies [12]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has formulated guidelines for instrument development for quality of life assessment in children. According to these, the measures should be self-centred, self-reported, age-dependent, and cross-culturally comparable [14]. Six generic quality of life instruments for children and adolescents that satisfy the criteria of suitability for ill and healthy respondents, availability in different languages, self-report and proxy-report versions, and tested psychometric quality will be briefly introduced here [8, 28].

One quality of life questionnaire is the Child Health Questionnaire [CHQ; 20], which is available in different versions (28–98 items) for children and parents and provides results on various subscales of quality of life. This measure was originally developed in the US and was then translated into several languages.

The Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory [PedsQL; 36] comprises four generic subscales and has additional disease-specific modules. Different versions for proxy- and self-reports are available.

Another instrument originally developed in the US is the Child Health and Illness Profile [CHIP; 34], which consists of 188 items in the long and 45 in the short form for children.

While the above-mentioned quality of life measures for children have all been developed in the English language and then translated [4], the generic KINDL-R questionnaire is a German-language measure to be used in healthy as well as clinical populations (originally developed by Bullinger et al. [3]; revised by Ravens-Sieberer and Bullinger [25]). The KINDL-R has also been translated into several languages (http://www.kindl.org).

The Netherlands Organisation for Applied Scientific Research-Academic Medical Centre child quality-of-life questionnaire [TACQOL, 37] is another instrument developed in Europe. It consists of 56 items covering seven domains and is available in self- and proxy-report versions.

An example of a cross-culturally applicable measure developed following various cross-cultural approaches is the KIDSCREEN [18] instrument. The KIDSCREEN project was funded by the 5th EU framework program and collaborated strongly with its sister project DISABKIDS [10, 21, 26]. Both projects were organised into three project phases: preparation, pilot study, and field study with implementation [29]. The goal of the KIDSCREEN project was to develop a family of generic quality of life measures for children and adolescents aged between 8 and 18 years. DISABKIDS aimed at constructing measures that assess the quality of life of chronically ill children. It was developed simultaneously in several European countries. KIDSCREEN can be used as a screening, monitoring, and evaluation tool in representative national and European health surveys (http://www.kidscreen.de).

This short review shows that several paediatric quality of life instruments that comply with the WHO criteria have been developed. They follow generic as well as disease-specific approaches [4]. Nonetheless, their use in epidemiological research and clinical trials is still extendable.

The goal of the current paper was to evaluate the KINDL-R questionnaire in a representative, population-based sub-sample of the KiGGS survey. Of special importance is how children rate their subjective health. Regarding the self-ratings of children, it is important to know how reliable these assessments are and how they correspond with the proxy-ratings of parents. The relationship between gender, age, and mental health problems will be further examined.

The German health interview and examination survey for children and adolescents (KiGGS) selected a representative sample of 17,641 children and adolescents. The obtained data included objective information on physical and mental health as well as parent- or self-reported information regarding subjective health status, health behaviour, health care utilisation, and sociodemographic data [19, 24]. The core survey is supplemented by three modules, namely environmental impact, mental health, and motor development. The BELLA study [31] represents the mental health module and provides further information on behavioural problems and subjective well-being. Within this focused approach, additional instruments assessing quality of life as well as protective factors were administered.

Methods

Between May 2003 and May 2006, 17,641 randomly recruited children and adolescents between 0 and 17 years participated in the German health interview and examination survey (KiGGS) [19]. Within the scope of the BELLA study, 4,199 families and children (7–17 years old) were randomly selected and asked to take part in an additional telephone interview lasting approximately 30 min. Of the 4,199 selected families, 2,942 (70%) gave consent to the supplementary interview; of which 2,863 (97%) finally participated.

Parents as well as children above the age of 11 years were questioned using a standardised computer-assisted telephone interview. Additionally, participants were asked to fill out a mailed paper and pencil questionnaire. To correct for deviation of the sample, data were weighted according to the age-, gender-, regional-, and citizenship-structure of the German population (reference data 31 December 2004).

Instruments

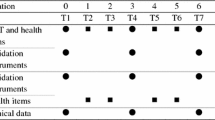

The BELLA study surveyed a representative German sample using different instruments for well-being as well as psychiatric and physical health. This allows for a comparison of different quality of life measures, considering their psychometric properties and scale structure.

KINDL-R

The KINDL-R questionnaire comprises 24 items [25] to which the respondents are asked to respond on a 5-point Likert scale (never, seldom, sometimes, often, all the time). The resulting subscales are physical well-being, emotional well-being, self-esteem, family, friends, and everyday functioning (school or nursery school/kindergarten). The subscales of these six dimensions can be combined to produce a total score. Sum scale scores can be calculated by summing up the answer scores (1–5) of each scale. It is also possible to transform all scales so that values range from 0 to 100, with higher values representing better quality of life. Psychometric properties have, thus far, been tested in a sample of school children and of chronically ill children in rehabilitation. Psychometric results revealed a high degree of reliability (Cronbach’s α ≥ 0.70 for most of the subscales and samples) and a satisfactory convergent validity of the procedure. Furthermore, the acceptance of the measure by children and adolescents is high [25]. The questionnaire was able to distinguish between children with different physical disorders and under different types of strain. Overall, the KINDL-R has proven to be a flexible, modular, and psychometrically acceptable method of measuring quality of life in children by means of a central module covering generic aspects in children’s quality of life. Age-specific versions take into account the changes in the quality of life dimensions over the course of the child’s development.

KIDSCREEN

The KIDSCREEN instruments assess children’s and adolescents’ subjective health and well-being. Three KIDSCREEN instruments are available in child and adolescent as well as parent/proxy versions: KIDSCREEN-52 (long version) [30], which covers ten HRQoL dimensions, KIDSCREEN-27 (short version), which covers five HRQoL dimensions, and the KIDSCREEN-10 index, which produces a global HRQoL score. Scores can be calculated for each dimension. In this study, the KIDSCREEN-52, which allows detailed profile information for ten HRQoL dimensions (physical well-being, psychological well-being, moods and emotion, self-perception, autonomy, parent relation and home life, financial resources, peers and social support, school environment, social acceptance (bullying)), was used. T values and percentages of scores for several countries stratified by age and gender are available.

SDQ

The strengths and difficulties questionnaire [15] comprises 25 items (rated as “not true”, “somewhat true”, or “certainly true”) and assesses behavioural and emotional problems, hyperactivity, peer problems, and social behaviour. A total problem score can be calculated by summing up the scores in the four problem areas. This score can be regarded as “normal”, “borderline”, or “abnormal” via cut-off values derived from the English norm data [16].

Additional variables

The analysis also included information on chronic illness, family climate, personal resources, social support, and parental support [13].

Chronic illness was assessed using the children with special health care needs (CSHCN) screener [1]. The CSHCN refers to prescription medicine, need of support, functional limitations, special therapies, as well as emotional, developmental, and behavioural problems. On the basis of the parents’ answers, children were classified into those with and those without a need for special health-related services.

A modified version of the family climate scale [33] (consisting of nine statements concerning activities within the family and caring for each other) was administered, offering answering options from “not true” to “exactly true”.

Parental support was assessed using a scale previously administered in the “Health behaviour in school-aged children” study [HBSC; 9]. On this scale, children rate the supportiveness of their parent(s) on eight items.

The German translation of the social support scale [11] was used to assess the social support the respondent receives. The modified version excluded items not applicable for children and adolescents. The resulting eight items are answered using a 5-point scale.

General personal resources were measured as an aggregated score by a scale developed in the pre-test of the survey [2]. Using five items, it inquires about individual attributes of the child such as self-efficacy, optimism, and sense of coherence. The four response categories range from “not true” to “exactly true”.

Statistics

The psychometric evaluation of the KINDL-R questionnaire included testing for its reliability and validity. Convergent and discriminant validation was analysed by correlating the subscales of the two questionnaires. The ability of the measures to discriminate between children with mental health problems and healthy respondents was performed via the known group approach (normal, borderline, or abnormal SDQ problem scores [15] and differences in quality of life ratings). This approach has been widely used in health outcomes research.

First, an item analysis was carried out using the multitrait analysis program from New England Medical Centre of Tufts University in Boston (MAP) [17]. Correlations of items with the scale, the scale fit to measure factorial validity, as well as internal consistency were determined. Convergent validity was tested by correlating KINDL-R subscales with the KIDSCREEN-52 using statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS).

The correlation between children’s and parents’ KINDL-R scores was analysed using Pearson’s correlation coefficients. The difference between groups of patients with regard to the SDQ score and the presence of a chronic illness was analysed using one-way ANOVA. Stepwise regression analysis was used to determine variables affecting variations of KINDL-R total score. The confidence interval was set at 95% and a significance level of P < 0.05 was used. Effect sizes of d > 0.5 and η² > 0.04 were regarded as medium, whereas effect sizes of d > 0.8 and η² > 0.16 were regarded as large.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

In this analysis, 1,867 children and adolescents (913 girls and 954 boys) were included. The mean age was 14.18 years (11–17 years old). Most of the children and adolescents attended secondary schools. Almost 50% were middle class children and one quarter were of low or high social class. Of the sample, 11.8% had a migration background, meaning that either they had migrated from a foreign country and had at least one parent not born in Germany, or both parents migrated from a foreign country or had no German citizenship. Furthermore, 15% of the children and adolescents were chronically ill and 10.3 (6.9%) were abnormal according to the SDQ problem score (see Table 1).

Internal consistency

The MAP analysis of the KINDL-R self-report data was carried out with 1,698 children and adolescents, as 9.1% of the KINDL-R data had missing values. The analysis revealed a good utilisation of the scale width with floor and ceiling effects of less than 10%, except for the family subscale (which showed ceiling effects of 17%).

Scale fit was 85% or above for all subscales. The internal consistency for subscales reached values from α = 0.54 to α = 0.73, with an α = 0.82 for the total score (see Table 2).

Intercorrelations of KINDL-R subscales and KINDL-R total score

The self-reported KINDL-R subscales all correlated above r = 0.6 with the KINDL-R total score. Furthermore, interscale correlations were below 0.4, except for psychological well-being and friends (r = 0.48).

Correlations between child- and parent-report

The correlations between child- and parent-reported subscales diverged. While the correlations for physical well-being and family are above r = 0.5, the self-perception ratings show a correlation of r = 0.23 (see Table 3).

Correlations between KINDL-R and KIDSCREEN-52 subscales

The self-reported KINDL-R subscales and total score were correlated with the self-reported KIDSCREEN-52 subscales. The KINDL-R scales physical well-being, emotional well-being, self-esteem, family, friends, and everyday functioning (school) correspond to similar domains in the KIDSCREEN-52 questionnaire such as physical well-being, psychological well-being, self-perception, parent relation and home life, social support and peers, and school environment. The analysis shows correlations between r = 0.41 and 0.53 for analogue subscales; however, the correlations for the self-perception subscales are somewhat lower (r = 0.23). The KINDL-R total score correlates with all KIDSCREEN-52 dimensions above r = 0.3 (see Table 4).

Discriminant validity of KINDL-R scores

In order to measure discriminant validity, the sample was divided into children and adolescents with and without a chronic disease. Differences among the groups are shown in Fig. 1. Differences are significant for all subscales and effect sizes range from d = −0.27 to d = 0.58. Furthermore, SDQ problem scores (rated by children) were used to differentiate between normal, borderline, and abnormal subgroups. Significant differences exist in all subscale ratings as well as in the total score (see Fig. 2). Post hoc Bonferroni tests reveal that differences exist among all groups, except cases where differences were significant between normal and abnormal, but not between borderline and abnormal subjects.

Determinants of KINDL-R scores

In addition to psychometric testing, a linear regression analysis was carried out. The variables entered into the regression model were age, gender, total problem score (SDQ), family coherence, personal resources, social support, and parental support. The findings demonstrate that 58.9% (r² = 0.589) of the variance could be explained by these variables. These results are shown in Table 5.

Discussion

Using the data from the BELLA study, a psychometric testing of the KINDL-R questionnaire was performed in a representative sample of children and adolescents in Germany. In the 1,867 children and adolescents between 11 and 17 years, the KINDL-R self-report questionnaire showed moderate to good scale properties in terms of floor and ceiling effects as well as scale fit. Ceiling effects above 10% were only apparent for the family subscale. In terms of reliability, the subscales showed moderate internal consistency. Interestingly, the psychometric properties of the KINDL-R in chronically ill populations appeared to be somewhat higher [25].

Correlations between the KINDL-R self-report questionnaire and the KIDSCREEN-52 questionnaire subscales have been shown. Equivalent subscales, except for the self-esteem subscale, correlate highly. Furthermore, the data reveal that the KIDSCREEN-52 questionnaire measures additional domains (namely autonomy, bullying, and financial burden) that are not highly reflected in the KINDL-R questionnaire and, therefore, do not correlate well with the KINDL-R. In addition, this analysis shows that self-esteem is a concept that differs in content in the two questionnaires or for which reliable measurement is more difficult than for other concepts.

The KINDL-R questionnaire was also able to differentiate between chronically ill and healthy children as well as between children with high and low problem scores on the SDQ.

A regression analysis showed that more than 50% of the variance of the KINDL-R total score can be explained by psychosocial variables such as family coherence and personal resources. This indicates the importance of personal, social, and family-based resources for quality of life in children and adolescents. This is in line with previous results [10, 18] on the role of psychosocial determinants in quality of life assessment and suggests that interventions to improve quality of life should also focus on these resources.

Correlations between child and parent ratings of quality of life were low to moderate, indicating that self-report differs from parent-reports. This is in accord with other studies that showed similar differences between parents’ and children’s reports [32, 35], emphasising the need to assess HRQoL using self- as well as proxy-reports.

Overall, the KINDL-R instrument is a suitable questionnaire for children and adolescents that measures HRQoL through self-report. Through the testing of the instrument in a representative sample for German children and adolescents as well as their parents, reference values are available [27].

The KINDL-R remains one of the first comprehensive HRQoL instruments for children both with and without chronic health conditions in Germany, is available in several languages, and is increasingly used to assess well-being and functioning in children and adolescents. Together with international instruments, such as the KIDSCREEN [18] and the DISABKIDS [10] questionnaires, these instruments provide a set of tools for assessing paediatric HRQoL.

References

Bethell C, Read D, Stein RE, Blumberg SJ, Wells N, Newacheck PW (2002) Identifying children with special health care needs: development and evaluation of a short screening instrument. Ambul Pediatr 2:38–48

Bettge S, Ravens-Sieberer U (2003) Schutzfaktoren für die psychische Gesundheit von Kindern und Jugendlichen–empirische Ergebnisse zur Validierung eines Konzepts. Gesundheitswesen 65:167–172

Bullinger M (1997) Entwicklung und Anwendung von Instrumenten zur Erfassung der Lebensqualität. In: Bullinger M (ed) Lebensqualitätsforschung: Bedeutung—Anforderung—Akzeptanz. Stuttgart, Schattauer, pp 1–6

Bullinger M (2000) Lebensqualität— Aktueller Stand und neuere Entwicklungen der internationalen Lebensqualitätsforschung. In: Ravens-Sieberer U, Cieza A (eds) Lebensqualität und Gesundheitsökonomie in der Medizin Konzepte—Methoden—Anwendungen. Landsberg, Ecomed, pp 13–24

Bullinger M, von Mackensen S, Kirchberger I (1994) KINDL—Ein Fragebogen zur Erfassung der gesundheits- bezogenen Lebensqualität von Kindern. Sonderdruck Zeitschrift für Gesundheitspsychologie 1:64–77

Bullinger M, Schmidt S, Petersen C, Ravens-Sieberer U (2006) Quality of life-evaluation criteria for children with chronic conditions in medical care. J Public Health 14:343–355

Cieza A, Stucki G (2005) Content comparison of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) instruments based on the international classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF). Qual Life Res 14:1225–1237

Clarke SA, Eiser C (2004) The measurement of health-related quality of life (QOL) in paediatric clinical trials: a systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2:66

Currie C, Samdal O, Boyce W, Smith R (eds) (2001) Health behaviour in school-aged children: a WHO Cross-National Study (HBSC). Research protocol for the 2001/2002 survey. Child and Adolescent Health Research Unit (CAHRU), University of Edinburgh

Donald CA, Ware JE (1984) The measurement of social support. Res Community Ment Health 4:325–370

Eiser C, Morse R (2001) Can parents rate their child’s health-related quality of life? Results of a systematic review. Qual Life Res 10:347–357

Erhart M, Hölling H, Bettge S, Ravens-Sieberer U, Schlack R (2007) Der Kinder- und Jugendgesundheitssurvey: Risiken und Ressourcen für die psychische Entwicklung von Kindern und Jugendlichen. Bundesgesundheitsbl — Gesundheitsforsch — Gesundheitsschutz 50:800–809

Gerharz EW, Ravens-Sieberer U, Eiser C (1997) Kann man Lebensqualität bei Kindern messen? Akt Urol 28:355–363

Goodmann R (1997) The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 38:581–586

Goodmann R, Meltzer H, Bailey V (1998) The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a pilot study on the validity of the self-report version. Eur J Child Adolesc Psychiatry 7:125–130

Hays R, Hayashi T (1990) Beyond internal consistency reliability: rationale and users guide for the multitrait analysis program on the microcomputer. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput 23:167–169

Kurth BM (2007) Der Kinder- und Jugendgesundheitssurvey: Ein Überblick Über Planung, DurchfÜhrung und Ergebnisse aus Sicht eines Qualitätsmanagements. Bundesgesundheitsbl-Gesundheitsforsch-Gesundheitsschutz 50:533–546

Landgraf JM, Abetz L, Ware JE (1996) Child health questionnaire: a user’s manual. The Health Institute, New England Medical Center, Boston

Petersen C, Schmidt S, Power M, Bullinger M (2005) Development and pilot-testing of a health-related quality of life chronic generic module for children and adolescents with chronic health conditions: a European perspective. Qual Life Res 14:1065–1077

Radoschewski M (2000) Gesundheitsbezogene Lebensqualität—Konzepte und Maße. Entwicklungen und Stand im Überblick. Bundesgesundheitsbl-Gesundheitsforsch-Gesundheitsschutz 43:165–189

Rajmil L, Herdman M, De Sanmamed M, Detmar S, Bruil J, Ravens-Sieberer U, Bullinger M, Simeoni M, Auquier P, and the KIDSCREEN Group (2004) Generic health-related quality of life instruments in children and adolescents: a qualitative analysis of content. J Adolesc Health 34:37–45

Ravens Sieberer U, Gosch A, Abel T, Auquier P, Bellach B, Bruil J, Dür W, Power M, Rajmil L, Bullinger M (2001) Quality of life in children and adolescents—a European public health perspective. Soz Praventivmed 46:294–302

Ravens-Sieberer U, Bullinger M (1998) Assessing health related quality of life in chronically ill children with the German KINDL: first psychometric and content analytical results. Qual Life Res 7:399–407

Ravens-Sieberer U, Bettge S, Erhart M (2003) Lebensqualität von Kindern und Jugendlichen—Ergebnisse aus der Pilotphase des Kinder- und Jugendgesundheits-surveys. Bundesgesundheitsbl-Gesundheitsforsch-Gesundheitsschutz 46:340–345

Ravens-Sieberer U, Gosch A, Rajmil L, Erhart M, Bruil J, Duer W, Auquier P, Power M, Abel T, Czemy L, Mazur J, Czimbalmos A, Tountas Y, Hagquist C, Kilroe J, and the European KIDSCREEN Group (2005) KIDSCREEN-52 quality-of-life measure for children and adolescents. Expert Rev Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res 5:353–364

Ravens-Sieberer U, Erhart M, Bullinger M (2006) The Kidscreen and Disabkids questionnaires—two measures for children and adolescent’s health related quality of life. Patient Reported Outcomes Newsl 37:9–11

Ravens-Sieberer U, Erhart M, Wille N, Wetzel R, Nickel J, Bullinger M (2006) Generic health-related quality-of-life assessment in children and adolescents: methodological considerations. Pharmacoeconomics 24:1199–1220

Ravens-Sieberer U, Erhart M, Wille N, Bullinger M, BELLA study group (2008) Health-related quality of life in children and adolescents in Germany: results of the BELLA study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 17(Suppl1):148–156

Ravens-Sieberer U, Kurth B-M, KiGGS study group, BELLA Study Group (2008) The mental health module (BELLA study) within the German Health Interview and Examination Survey of Children and Adolescents (KiGGS): study design and methods. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 17(Suppl1):10–21

Redegeld M (2003) Lebensqualität chronisch kranker Kinder und Jugendlicher- Eltern- vs. Kinderperspektive. Verlag Dr. Kovač, Hamburg

Schneewind K, Beckmann M, Hecht-Jackl A (1985) Familienklima-Skalen. Bericht 8.1 und 8.2. Institut für Psychologie—Persönlichkeitspsychologie und Psychodiagnostik. Ludwig Maximilians Universität, München

Starfield B, Riley AW, Green BF, Ensminger ME, Ryan SA, Kelleher K, Kim-Harris S, Johnston D, Vogel K (1995) The adolescent child health and illness profile. A population-based measure of health. Med Care 33:553–566

The DISABKIDS GROUP EUROPE (2006) The DISABKIDS-questionnaires for children with chronic conditions. Papst Science Publishers, Lengerich

The KIDSCREEN Group Europe (2006) The KIDSCREEN questionnaires— quality of life questionnaires for children and adolescents. Handbook. Pabst Science Publishers, Lengerich

Theunissen NC, Vogels TG, Koopman HM, Verrips GH, Zwinderman KA, Verloove-Vanhorick SP, Wit JM (1998) The proxy problem: child report versus parent report in health-related quality of life research. Qual Life Res 7:387–397

Varni JW, Seid M, Rode CA (1999) The PedsQL: measurement model for the pediatric quality of life inventory. Med Care 37:126–139

Vogels T, Verrips GHW, Verloove-Vanhorick SP, Fekkes M, Kamphuis RP, Koopman HM, Theunissen NCM, Wit JM (1998) Measuring health-related quality of life in children: the development of the TACQOL parent form. Qual Life Res 7:457–465

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Members of the BELLA study group: Ulrike Ravens-Sieberer (Principal Investigator), Claus Barkmann, Susanne Bettge, Monika Bullinger, Manfred Döpfner, Michael Erhart, Beate Herpertz-Dahlmann, Heike Hölling, Franz Resch, Aribert Rothenberger, Michael Schulte-Markwort, Nora Wille, Hans-Ulrich Wittchen.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bullinger, M., Brütt, A., Erhart, M. et al. Psychometric properties of the KINDL-R questionnaire: results of the BELLA study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 17 (Suppl 1), 125–132 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-008-1014-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-008-1014-z