Abstract

Evidence has shown that the trend of increasing obesity rates has continued in the last decade. Mobile phone applications, benefiting from their ubiquity, have been increasingly used to address this issue. In order to increase the applications’ acceptance and success, a design and development process that focuses on users, such as user-centred design, is necessary. This paper reviews reported studies that concern the design and development of mobile phone applications to prevent obesity, and analyses them from a user-centred design perspective. Based on the review results, strengths and weaknesses of the existing studies were identified. Identified strengths included: evidence of the inclusion of multidisciplinary skills and perspectives; user involvement in studies; and the adoption of iterative design practices. Weaknesses included the lack of specificity in the selection of end-users and inconsistent evaluation protocols. The review was concluded by outlining issues and research areas that need to be addressed in the future, including: greater understanding of the effectiveness of sharing data between peers, privacy, and guidelines for designing for behavioural change through mobile phone applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Recent evidence shows that the worldwide obesity rate is increasing and has more than doubled since 1980 [1]. The latest data from the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) showed that more than one-third of US adults were obese, with adults aged 60 and over more likely to be obese than younger adults [2]. Similar trends have been reported in Europe, where between 30 and 80 % of adults are obese with higher prevalence of obesity among men than women [3]. Obesity and being overweight have considerable effects on morbidity and mortality through various diseases such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and metabolic syndrome [3]. Obesity yields negative economic consequences as a result from direct costs (increased medical costs to treat the associated diseases), indirect costs (lost productivity due to absenteeism or premature death) and intangible costs (psychological problems and poorer quality of life). Fry and Finley [4] revealed that the total direct and indirect costs for the 15 countries that were European Union members before May 2003 were estimated to be €32.8 billion per year, while for United States the estimated cost was US$147 billion [5]. Nagai et al. [6] reported that in spite of shorter life expectancy, individuals that are obese still require higher lifetime medical expenditures than those of normal weight. These costs are likely to increase as the prevalence of obesity increases [7].

The above factors have prompted initiatives to prevent obesity which range from the implementation of public health policies such as nutrition labelling [8], unhealthy food and drinks tax [9], to interventions by means of mobile phone applications to promote healthy eating and increased physical activity [10]. Some literature reviews, which have studied the effectiveness of obesity prevention through mobile phone applications, reported a mixed outcome of the intervention effectiveness [11, 12]. Although these reviews suggest possible factors that contributed to this phenomenon, none of them looked into the design process of these applications and how it might affect their successful adoption by the target users. It has been widely acknowledged through a variety of studies that failure in understanding users during design and development of any product or system can results in a low acceptance and effectiveness [13]. One approach to ensuring successful product or system design is the application of user-centred design (UCD), first introduced by Norman and Draper [14]. UCD refers to how end-users influence a design through their involvement in the design processes and has been shown to contribute to the acceptance and success of products [15]. This paper presents a review of the extent to which the design processes of existing mobile phone applications to prevent obesity have incorporated the principles of UCD. Our objectives were: (i) to identify key principles of UCD that were applied to develop existing mobile applications to obesity prevention; (ii) to analyse the strength and weakness of their design approaches and processes; and (iii) to identify any gaps in the research and propose future directions.

This paper begins by describing UCD in detail and is followed by explanation on how studies that were included in the review were identified and analysed. Next, the results of the review are explained in detail. The last two sections of the paper discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the reviewed studies and emerging issues and future research questions that need to be addressed to advance our understanding. This paper’s main contribution lies in the identification of gaps within this research area from a UCD viewpoint and how to address these gaps through recommendations for future research.

2 User-centred design

UCD is a common term, encompassing a philosophy and variety of methods, which refers to how end-users influence a design through their involvement in the design process. The level of user involvement in UCD varies and can range from a simple observation of end-users in their working environment to including user representatives on the design team. Key principles associated with UCD (ISO 9241-210:2010) are described as follows:

-

Clear understanding of users, tasks and environments. Explicit understanding of the characteristics of users, tasks and environments enables identification of the context in which a system will be used by users. This context of use subsequently assists in establishing users’ and/or organisations’ requirements and relevant usability goals. Approaches such as stakeholder identification and analysis, field study, user observation and task analysis can be adopted to gain an understanding of users, tasks and environments [16].

-

User involvement throughout design and development. Active user involvement should be upheld throughout the design and development process of a system. This could be achieved through various ways, such as including end-users or their representatives in a design team, consulting potential end-users and relevant stakeholders to assist requirements gathering and involving end-users in usability testing [17].

-

Driving and refining design through user-centred evaluation. This key principle emphasises the importance of user-centred evaluation to inform a design and to improve it at all stages. Typical activities include presenting low or high prototyping and storyboarding to potential end-users, post-experience interviews and satisfaction questionnaires of preliminaries design, etc. [18].

-

Iterative design process. Making the design process iterative is a way of ensuring that users can get involved in the design and that different kinds of knowledge and expertise can be brought into play as needed [15]. Iterative design processes can be identified through integration of the formative evaluation outcome into later or final designs.

-

Addressing the whole user experience. This key principle emphasises how a design should also consider the quality of a user’s experiences while interacting with a specific design and not focus solely on usability, i.e. whether or not a design is effective and efficient. In other words, a design should promote positive emotions and feelings to users while interacting with it [19]. Attempts to address user experience can be identified through the use of interviews and/or distribution of questionnaires which probe end-users’ experiences after using a system.

-

Inclusion of multidisciplinary skills and perspectives. A range of views, including those of non-technical specialist experts, end-users, relevant stakeholders, etc. is required during the design and development of a system [15]. This could take the form of a consultation with and/or inclusion of these people in a design team.

3 Methods

The articles included in this review were primarily identified from a meta-search on engineering databases which included ANTE, ACM DL, Ei Compendex, IEEE Wiley eBooks Library, IEEE/IET Electronic Library, INSPEC (Ovid), INSPEC Archive (Ovid) and Zetoc. The search was limited to English language communications in peer-reviewed journals, conferences and books that were published between 2000 and 2012. Only articles that reported the utilisation of mobile phones to promote healthy eating and physical activity were included in the review. The following terms “obesity phone”, “physical activity” and “phone” and “obesity”, “weight loss” and “phone” were used to perform the search. As this review focuses on obesity, articles that reported the use of mobile phone applications for other purposes, e.g. diabetes patient monitoring, rehabilitation, wellness monitoring for elderly, etc., were not included in the review. Furthermore, articles, which focused on sensing devices and their mechanisms, or were limited to blueprints/concepts of mobile phone applications to prevent obesity, were also excluded from the review.

For each study, we asked the following questions: (1) “How is the created mobile phone application used to prevent obesity?” (2) “What key principles of UCD were adopted during its design and development process and how were they applied?” (3) “Was the mobile phone application effective and what measures were used to determine its success?” For the second question, design and research activities that were relevant for each key criterion were identified. It is acknowledged that the outcome of the assessment was largely affected by how much details of the design and research activities were reported or published. To minimise the effects of this issue, all publications related to a website or mobile phone application were tracked and included in the review. For the third question, only studies that reported deployment of their applications to users in real-life situation were reviewed.

The review method adopted in this paper is largely based on research literature from scientific publications and does not survey the many commercial mobile phone applications that have been developed in recent years. One reason for this decision is that, unlike for research literature, there is no systematic way to get a comprehensive overview of commercial products. The other reason is that our goal was to provide an overview of the design and development process of mobile phone applications and this information is not likely to be easily accessible in the commercially sensitive private sector.

4 Results

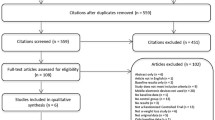

Figure 1 provides a flow chart documenting the results of the study selection process which resulted in the inclusion of 52 mobile phone applications in this review. As the review was based only on scientific publications and excluded those that are available commercially, it has to be noted that the list of the mobile applications for obesity prevention is not necessarily exhaustive.

An overview of the mobile applications included in the review is shown in “Appendix 1”. A quick glance on this suggested that more than half of the applications design (33 articles—63.5 %) did not incorporate theories or principles that could encourage behavioural changes, despite aiming to do so. Although incorporation of relevant theories into applications does not necessarily guarantee the success of applications in inducing changes of behaviour, there is a strong likelihood that such a system would likely be more capable in achieving this through design. For instance, in mobile snack, Khan et al. [63] incorporated the transportation theories [13, 112, 113] and precaution adoption process model [114] by providing an immersive animation-based narrative that depicted the game characters’ progressive life stages based on their eating behaviour. They also applied social cognitive theory [115] by allowing users to view their eating behaviour history and compare themselves with other users. The overview results also suggested that only a minority of the reviewed studies defined the specific end-users for whom their applications were targeted and instead opted for a broad definition of end-users, e.g. individuals with obesity or overweight issues, individuals with sedentary lifestyle. Having such a broad definition of users will potentially result in overlooking some users and limit the applications’ effectiveness. For instance, users of UbiFit, a tracking application that provided feedback on users’ physical activity level through a garden metaphor on its glanceable display, preferred to have metaphors for displays that suited their interests [97, 98]. A similar thing was also experienced by users of Neat-O, a game application that motivates its users to compete against each other based on their physical activity level and rewards them with choice of mini games. In this instance, users suggested adjustments on the type of mini games provided based on age groups as well as pop-up motivational statements appropriate for different gender [73].

This paper revealed that mobile phone applications to prevent obesity can be grouped into four categories. These were as follows: a tracking assistant (assisting a user in tracking and reviewing his/her behaviour), an entertainment tool (persuading a user to adopt an intended behaviour through game), an advisory assistant (advising a user to adopt an intended behaviour) and a tool to leverage social influence (providing a platform for a user to interact with his/her peers to encourage adoption of an intended behaviour). Figure 2 shows the proportion of mobile phone applications in each category. The lower proportion of mobile phone application’s role as advisory and enforcement of social influence is likely due to the recent availability of mobile social network platforms and GPS technologies. As such, smart phone applications in these categories are expected to grow in numbers in the future. It is also expected that social network platforms and GPS technologies will be important part of future applications of the first two categories.

A further examination revealed that the majority of the reviewed studies produced fully functioning prototypes (see “Appendix 2” for a review of the mobile phone applications from a UCD perspective). Unfortunately, it also appears that these prototypes were not necessarily developed based on a thorough understanding of users or how and when they would use these applications. Only 30.8 % of the reviewed studies indicated any design activities that involved either targeted users or relevant stakeholders prior to the design of applications. Incidentally, although the majority of the reviewed studies (88.5 %) either performed or at least planned an evaluation study that involved end-users, only less than half of the reviewed studies (42 %) demonstrated that the application designs were refined through user-centred evaluation prior to the development of fully functioning prototypes. Furthermore, only 46 % of the reviewed studies indicated the existence of an iterative design process. All of the above findings indicate that user-centred design principles were not fully adopted by researchers while designing existing mobile phone applications. These findings also suggest that the design for the functions and features of the applications was driven in the majority by perceptions of the application designers on users’ needs and requirements. Coupled with the fact that these studies adopted a broad definition of end-users, there is a strong likelihood that the end product is a mismatch for the targeted end-users. Unfortunately, it was not possible to identify from the reviewed paper what might cause this phenomenon. Vredenburg et al. [18] emphasised the importance of user involvement to support understanding of user and iterative development throughout the design and development of a system. During the early stage, user involvement is valuable to provide support for design decisions as well as problem detections of a system; while at a later stage, it can help to verify the quality of a system. Failure to provide adequate user involvement means that changes at later stages are likely to occur and be more costly or difficult to be accommodated. For instance, Buttusi and Chitaro [64], who designed Monster and Gold game application, discovered only after user evaluation that their application could be repetitive if used several times due to lack of game setting varieties. Another example is Fukuoka et al. [70], who designed mPED that sent daily messages to suggest context-aware physical activity, overlooked the users’ need for personalisation and variation of encouraging messages and only discovered at a late stage some of their end-users considered found this to be source of disappointment.

Most of the reviewed studies (63.5 %) addressed the whole user-experiences while evaluating their functioning prototypes. This finding suggests that designers acknowledged the importance of assessing user experience, especially when long-term engagement is required. All of the reviewed studies conducted interviews to investigate user experience. Although interviews enable an in-depth understanding, they present a challenge for comparison studies. Using a set of established questionnaires, such as AttrakDiff [116] is expected to resolve this issue. Last but not least, it was found that most of the reviewed studies (73 %) indicated the inclusion of multidisciplinary skills and perspectives during their application design and development. This proportion is high as various aspects such as the presence of underlying behavioural change theories, consultation with experts/users and inclusion of experts/users in the design team, were used as indicators.

Table 1 shows the evaluation results of the reviewed studies, which produced fully functioning prototypes and which were deployed to users for more than one day. Out of the 52 studies, only 14 (27 %) conducted field studies with their targeted end-users, with deployment of the applications ranging from one day to three months. This finding suggests that, at the moment, most of the research effort was concentrated on the development of the applications and lack of attention was paid to investigate their effectiveness. It is possible that this phenomenon occurred due to the continuous and fast-paced technological development related to mobile phones, which consequently encourages more research to investigate the latest technology utilisation and leaves little time to study its effectiveness. For instance, based on the reviewed paper, the incorporation of a mobile phone’s camera to assist automatic recording of food intake was only initiated in 2008, and as the time progressed, the complexity of technology used also increased, i.e. from simply using a camera [45, 46, 91–93] to video camera [39] and a combination of a video camera and laser-generated grid [37, 38].

The review showed that nearly all of the studies collected qualitative data (related to usability and/or user-experiences) and quantitative data simultaneously. The type of quantitative measurements that were collected by most of the studies differed from one study to another although all of them aimed to capture how their applications prompted behavioural changes. As a result, performing comparison of effectiveness between applications will likely be difficult if not impossible. Furthermore, taking into account that most of the applications were aimed at preventing obesity, it was quite surprising that only a few of the reviewed studies used weight change as one of their quantitative evaluation measurements. It is acknowledged that, as some of the studies only focused on one particular thing (either physical activity or eating behaviour), changes in weight do not provide an independent measure as it is affected by both physical activity and eating behaviour. With regards to the results of the evaluation, it is clear that more research is needed to provide firm evidence on the effectiveness of mobile phone applications to prevent obesity. All of the 14 reviewed studies suggested that mobile phone applications have the potential to encourage change of behaviour to prevent obesity. However, it is difficult to ascertain if the observed potential will be sustained on a long-term basis since only two studies out of 14 studies deployed their applications for 3 months. A similar problem has been experienced in establishing the effectiveness of internet based and video game to combat obesity [117–119]. Mattila et al. [108] even suggested that mobile phone applications will not be effective unless they are part of an intervention which “provides the initial motivation and engagement that enable users to reach the ‘long-term’ stage”.

5 Strengths and weaknesses of existing studies from UCD perspective

Based on the results of the review in Sect. 3, the strengths and weaknesses of existing studies from a UCD perspective were identified (see Table 2). Current studies have, to some extent, included multidisciplinary skills and perspectives through consulting and/or involving users early in the design and/or evaluation stage. However, there are limitations to the involvement of users as users’ knowledge of behavioural change domain and awareness of their own needs may be limited [120, 121]. Therefore, more effort should be made to incorporate relevant behavioural change theories into the design and development of mobile phone applications. A similar analogy to this is a creation of a virtual training system in which the training system’s content and delivery should still be based on training principles while its interface design and context of use are consulted with end-users or relevant stakeholders. As mentioned earlier, there is some evidence that users were involved during the development of mobile phone applications. However, most of the involvement occurred only in the formative evaluation with few, if any, taking place prior to this. Frequent end-user involvement could be impractical and costly as could perform major changes post-formative evaluation. Therefore, a design team should weigh the benefit and cost of each circumstance at the beginning of the project and use this judgement to make their decisions. The review also showed that iterative design practices were widely adopted across studies. However, the level of iterative design process varied between studies, with some studies only using the results of formative evaluation to improve their application design. Again, the same judgement made for user involvement explained above also applies. It should be noted that iterative design practices do not necessarily equate to higher level of user involvement in the design as the iteration could simply be triggered through less formal evaluation such as heuristic evaluation [122] or cognitive walk-through [123].

Some weaknesses of existing studies were also identified through the review. The most commonly noted is the lack of focus on specifying target end-users. Obtaining a full understanding of users will likely be a challenge if end-users are not fully specified from the beginning. This could result in the inability to thoroughly identify what they want from a design, how and when they will use it, what makes them want to use it, etc. There is strong evidence that behavioural change needs to be tailored to match an individual’s needs and characteristics in order to be effective and sustainable [124, 125]. Furthermore, by providing specific target end-users from the beginning, relevant stakeholders could be identified and potentially involved. A perfect example of this is a study by Toscos et al. [31], who having specified their targeted end-users as teenage girls, identified and consulted relevant stakeholders (dieticians) who then provided valuable suggestions to their initial design concept. Another common weakness that was observed from the reviewed studies is the way mobile phones applications were evaluated for their effectiveness in inducing change of behaviour. The first issue is the length of period, which is considerably short to observe permanent behaviour change. The reviewed studies showed that the longest observation period was 3 months minus the first week to establish a baseline. This is considerably shorter than Prochaska and Velicer [126] recommended minimum of 6 months. It was also found that different studies utilised different approaches to evaluate their application effectiveness, which in turn created difficulties in comparing the studies’ results. A possible option to resolve this was to adopt a randomized controlled trial (RCT), which is commonly used in the health sciences. Fukuoka et al. [71] have published their detailed plan to evaluate the effectiveness of their mobile phone application to increase physical activity in sedentary woman. However, it should be noted that RCT may not provide an indication of why or how the mobile phone application could induce behavioural change. Therefore, if the aim of the evaluation is to find out the reasoning behind an induced behavioural change, additional qualitative data should be collected. There was also a question raised regarding the type of variables that were used to gauge the effectiveness of applications. For example, of two mobile phone applications that aimed to educate about healthy eating through game, one measured their application’s effectiveness based on the frequency of use [73]; the other based it on the frequency of users’ negative behaviour [95].

6 Emerging issues and future research directions

Following the increased acceptance of social network platforms and enthusiasm to share information publicly, it is expected that more and more mobile phone applications will enable sharing between peers. Sharing has been shown to have a positive relationship with inducing change of behaviour as a result of social pressure, support and accountability among members of a group [127, 128]. However, some of the studies that have incorporated this feature into their applications have reported issues that resulted from sharing such as unhealthy competitiveness [129], negative impacts if a desired response from peer was not received [30] and breach of privacy. More research will be required to avoid these issues while maximising the benefit of sharing between peers. Breach of privacy could also be an issue for mobile phone applications that integrate automatic sensing in various forms such as GPS, microphone and accelerometer. Klasnja et al. [130] reported that users’ perception towards breach of privacy is influenced by the type of data that is recorded, the context in which participants worked and lived and the value they perceived would be gained in return. They suggested preventive measures such as adopting conservative recording and data retention policies, graded functionality for the sensors, and giving users visibility and control over sensors usage. An issue that is unique to mobile phone applications with an advisory function is ensuring the appropriateness of suggestion with users’ lifestyles and activities as well as the ability to ignore it. Fukuoka et al. [70], who sent daily random message to their application’s users and required a subsequent response, found that only 39 and 34 % of users would like to receive it once and twice a day, respectively. However, a study by Mutsuddi and Connelly [131] showed that tailoring suggestions is less crucial when an application is deployed to users who are in the contemplation and preparation stages of change as they would likely more receptive to suggestion.

Throughout the review process of this paper, it was observed that there are limited guidelines on how to design effective mobile phone application interventions to sustain behavioural change. Although some research has begun to contribute to this topic, more research will be required in the future. Fogg [132], through his persuasive design concept, has proposed higher level abstraction that can be applied to persuade users while Consolvo et al. [100, 129] proposed several guidelines, which were drawn from the implementation of their applications and incorporation of behavioural change theories. Their proposal included appropriate reward for positive reinforcement, supporting social influence, taking into account the practical constraints of users’ lifestyles, reflection through abstraction, unobtrusive data collection and presentation, aesthetics, permitting the user to control their own data and enabling history/trend viewing. Another research direction for the future is a more comprehensive approach towards all dimensions of an individual’s life. Lenert et al. [133] suggested that the lack of comprehensive approach might be an avenue to engage users in the long term after an initial period of interests. A comprehensive approach is only feasible when information regarding users is obtained and understood thoroughly. This is crucial for mobile phone applications that aim to be context-aware. More research that is also needed in the future is establishing the effectiveness of mobile phone applications, which has already been discussed in detailed in the previous section.

7 Summary

As discussed above, from user-centred design perspective, the design and development process of mobile phone applications can certainly be improved by addressing its current weaknesses. Two main areas offered opportunities for improvement. The first is design of an application should be based on a combination of thorough understanding of users and their contexts of use, combined with principles from behavioural change theories. The second is a more robust approach in evaluating the effectiveness of mobile phone applications in terms of chosen quantitative measures, length of observation periods and how and why certain features are successful in supporting behaviour change. More work is required to establish guidelines that can be used to design and develop mobile phone applications to prevent obesity.

References

Finucane MM, Stevens GA, Cowan MJ, Danaei G, Lin JK, Paciorek CJ, Singh GM, Gutierrez HR, Lu Y, Bahalim AN, Farzadfar F, Riley LM, Ezzati M (2011) National, regional and global trends in body-mass index since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 country-years and 9.1 million participants. Lancet 377(8765):557–567. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62037-5

Ogden CL, Caroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM (2012) Prevalence of obesity in the United States 2009–2010. National Centre for Health Statistic Data Brief, 82

Branca F, Haik N, Lobstein T (2007) The challenge of obesity in the WHO European Region and the strategies for response: summary. WHO, Copenhagen

Fry J, Finley W (2005) The prevalence and costs of obesity in the EU. Proc Nutr Soc 64(3):359–362. doi:10.1079/PNS2005443

Finkelstein EA, Fiebelkorn IC, Wang G (2003) National medical spending attributable to overweight and obesity: how much and who’s paying? Health Aff 3:219–226. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.w3.219

Nagai M, Kuriyama S, Kakizaki M, Ohmori-Matsuda K, Sone T, Hozawa A, Kawado M, Hashimoto S, Tsuii I (2012) Impact of obesity, overweight and underweight on life expectancy and lifetime medical expenditures: the Ohsaki Cohort Study. BMJ Open 2(3). doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000940

Wang YC, McPherson K, Marsh T, Gortmaker SL, Brown M (2011) Health and economic burden of the projected obesity trends in the USA and UK. Lancet 378(9739):815–825. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60814-3

Ollberding NJ, Wolf RL, Contento I (2010) Food label use and its relation to dietary intake among US adults. J Am Diet Assoc 100(8):1233–1237. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2010.05.007

Mytton OT (2012) Taxing unhealthy food and drinks to improve health. Br Med J 344:e2931. doi:10.1136/bmj.e2931

Klasnja P, Pratt W (2012) Healthcare in the pocket: mapping the space of mobile-phone health interventions. J Biomed Inform 45:184–198. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2011.08.017

Lau PWC, Lau EY, Wong DP, Ransdell L (2011) A systematic review of information and communication technology-based interventions for promoting physical activity behavior change in children and adolescents. J Med Intern Res 13(3). doi:10.2196/jmir.1533

Kennedy CM., Powell J, Payne TH, Ainsworth J, Boyd A, Buchan I (2012) Active assistance technology for health-related behavior change: an interdisciplinary review. J Med Intern Res 14(3). doi:10.2196/jmir.1893

Damodaran L (1996) User involvement in the system design process—a practical guide for users. Behav Inf Technol 15(6):364–377

Norman DA, Draper SW (1986) User-centred system design: new perspective on human–computer interaction. Lawrence Earlbaum Associate, Hillsdale

Preece J, Rogers Y, Sharp H, Benyon D, Holland S, Carey T (1994) Human computer interaction. Pearson Education Limited, England

Maguire M, Bevan N (2002) User requirements analysis: a review of supporting methods. In: Proceedings of IFIP 17th World Computer Congress

Maguire M (2001) Methods to support human-centred design. Int J Hum Comput Stud 55:587–634

Vredenburg K, Isensee S, Righi C (2002) User-centred design: an integrated approach. Prentice-Hall, New Jersey

Hartson R, Pyla P (2012) The UX book: process and guidelines for ensuring a quality user experience. Elsevier, Waltham

Iglesias J, Cano J, Bernardos AM, Casar JR (2011a) A ubiquitous cavity-monitor to prevent sedentaries. In Proceedings of IEEE international conference on pervasive computing and communications

Iglesias J, Bernardos AM, Tarrio P, Casar JR, Martin H (2011b) Design and validation of a light inference system to support embedded context reasoning. Pers Ubiquit Comput

Fialho ATS, van den Heuvel H, Shahab Q, Liu Q, Li L, Saini P, Lacroix J, Markopoulos P (2009a) ActiveShare: sharing challenges to increase physical activities. In: Proceedings of the 27th international conference on human factors in computing systems. doi:10.1145/1520340.1520633

Fialho A, van den Heuvel H, Shahab Q, Liu Q, Li L, Saini P, Lacroix J, Markopoulos P (2009b) Virtual challenges: a social interaction approach to increasing physical activity. In: Wouters IHC, Tieben R, Kimman FFP, Offermans SAM, Nagtzaam HAH (eds) Flirting with the future: proceedings of the 5th student interaction design conference

Arteaga SM, Kudeki M, Woodworth A (2009) Combating obesity trends in teenagers through persuasive mobile technology. SIGACCESS Access Comput 94:17–25. doi:10.1145/1595061.1595064

Arteaga SM, Kudeki M, Woodworth A, Kurniawan S (2010) Mobile system to motivate teenagers’ physical activity. In: Proceedings of the 9th international conference on interaction design and children. doi:10.1145/1810543.1810545

Arteaga SM (2010) Persuasive mobile exercise companion for teenagers with weight management issues. SIGACCESS Access Comput 96:4–10. doi:10.1145/1731849.1731850

Denning T, Andrew A, Chaudhri R, Hartung C, Lester J, Borriello G, Duncan G (2009) BALANCE: towards a usable pervasive wellness application with accurate activity inference. In: Proceedings of the 10th workshop on mobile computing systems and applications. doi:10.1145/1514411.1514416

Andrew A, Denning T, Borriello G (2009) BALANCE: An engaging interface for long term wellness. In: Proceedings of the computer and human interactions 2009 conference

Hughes DC, Andrew A, Denning T, Hurvitz P, Lester J, Beresford S, Borriello G, Bruemmer B, Moudon AV, Duncan GE (2010) BALANCE (Bioengineering Approaches for Lifestyle Activity and Nutrition Continuous Engagement): developing new technology for monitoring energy balance in real time. J Diabetes Sci Technol 4(2):429–434

Toscos T, Faber A, An S, Gandhi MF (2006) Chick clique: persuasive technology to motivate teenage girls to exercise. In: Proceedings of the computer and human interaction 2006 conference. doi:10.1145/1125451.1125805

Toscos T, Faber A, Connelly K, Upoma AM (2008) Encouraging physical activity in teens: can technology help reduce barriers to physical activity in adolescent girls? In: Proceedings of pervasive computing technologies for healthcare. doi:http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.206.1225

Clark D, Edmonds C, Moore A, Harlow J, Allen K (2012) Android application development to promote physical activity in adolescents. In: Proceedings of 2012 international conference on the collaboration technologies and systems (CTS). doi:10.1109/CTS.2012.6261106

Allen K, Harlow J, Cook E, McCrickard DS, Winchester WW III, Zoellner J, Estabrooks P (2012) Understanding perceptions and experiences of cellular phone usage in low socioeconomic youth. In: Proceedings of the 33rd annual meeting and scientific sessions of the society for behavioral medicine

Schiel R, Kaps A, Bieber G (2012) Electronic health technology for the assessment of physical activity and eating habits in children and adolescents with overweight and obesity IDA. Appetite 58(2):432–437. doi:10.1111/j.1744-9987.2010.00903

Bieber G, Voskamp J, Urban B (2009) Activity recognition for everyday life on mobile phones. In: Proceedings of the 5th international on conference universal access in human–computer interaction. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-02710-9_32

Shang J, Sundara-Rajan K, Lindsey L, Mamishev A, Johnson E, Teredesei A, Kristal A (2011a) A pervasive dietary data recording system. In: Proceedings of IEEE international conference on pervasive computing and communications. doi:10.1109/PERCOMW.2011.5766890

Shang J, Sundara-Rajan K, Lindsey L, Mamishev A, Johnson E, Teredesei A, Kristal A (2011b) A mobile structured light system for food volume evaluation. In: Proceedings of IEEE international conference on computer vision workshops. doi:10.1109/ICCVW.2011.6130229

Shang J, Pepin E, Johnson E, Hazel D, Teredesai A, Kristal A, Mamishev A (2012). Dietary intake assessment using integrated sensors and software. In: Proceedings of SPIE 8304 multimedia on mobile devices. doi:10.1117/12.907769

Kong F, Tan J (2012) DietCam: automatic dietary assessment with mobile camera phones. Pervasive Mob Comput 8:147–163. doi:10.1016/j.pmcj.2011.07.003

Clawson J, Patel N, Starner T (2010) Dancing in the Streets: The design and evaluation of a wearable health game. In: Proceedings of the 2010 international symposium on wearable computers. doi:10.1109/ISWC.2010.5665864

Ho TC, Chen X (2009) ExerTrek: a portable handheld exercise monitoring, tracking and recommendation system. In: Proceedings of the 11th international conference on e-health networking, applications and services. doi:10.1109/HEALTH.2009.5406194

Laikari A (2009) Exergaming—gaming for health: a bridge between real world and virtual communities. In: Proceedings of the 13th IEEE international symposium on consumer electronics. doi:10.1109/ISCE.2009.5157004

Vaatanen A, Leikas J (2009) Human-centred design and exercise games: users’ experiences of a fitness adventure prototype. In: Kankaanranta M, Neittaanmaki P (eds) Design and use of serious games. Springer, Dordrecht

Chuah M, Sample S (2011) Fitness Tour: a mobile application for combating obesity. In: Proceedings of the first ACM MobiHoc workshop on pervasive wireless healthcare. doi:10.1145/2007036.2007048

Kitamura K, Yamasaki T, Aizawa K (2009) Food image analysis by local image feature. IEICE Tech Report 108(425):167–172

Aizawa K, de Silva GC, Ogawa M, Sato Y (2010) Food log by snapping and processing images. In: Proceedings of international conference on virtual systems and multimedia (VSMM). doi:10.1109/VSMM.2010.5665963

Chang T (2012) Food fight: A social diet network mobile application. Master Thesis, University of California

Wylie CG, Coulton P (2008) Mobile exergaming. In: Proceedings of 2008 international conference on advances in computer entertainment technology. doi:10.1145/1501750.1501830

Wylie CG, Coulton P (2009) Mobile persuasive exergaming. In: Proceedings of international IEEE consumer electronics society’s games innovations conference. doi:10.1109/ICEGIC.2009.5293582

Gao C, Fanyu K, Tan J (2009) Health aware: tackling obesity with health aware smart phone systems. In: Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE international conference on robotics and biomimetics. doi:10.1007/s11036-007-0014-4

Consolvo S, Everitt K, Smith I, Landay JA (2006) Design requirements for technologies that encourage physical activity. In: Proceedings of CHI 2006. doi:10.1145/1124772.1124840

Consolvo S, Harrison B, Smith I, Chen M, Everitt K, Froelich J, Landay JA (2007) Conducting in situ evaluations for and with ubiquitous computing technologies. Int J Hum Comput Interact 22(1):107–122. doi:10.1080/10447310709336957

Järvinen P, Järvinen T.H, Lähteenmäki L, Södergård C (2008) HyperFit: hybrid media in personal nutrition and exercise management. In: Proceedings of second international conference on pervasive computing technologies for healthcare. doi:10.4108/ICST.PERVASIVEHEALTH2008.2555

Macvean A, Robertson J (2012) iFitQuest: a school based study of a mobile location-aware exergame for adolescents. In: Proceedings of the 14th international conference on human–computer interaction with mobile devices and services. doi:10.1145/2371574.2371630

Macvean A (2012) Developing adaptive exergames for adolescent children. In: Proceedings of the 11th international conference on interaction design and children. doi:10.1145/2307096.2307162

Li I, Key AK, Forlizzi J (2012) Using context to reveal factors that affect physical activity. J ACM Trans Comput Hum Interact 19(1). doi:10.1145/2147783.2147790

Ahtinen A, Huuskonen P, Hakkila J (2010) Let’s all get up and walk to the north pole: design and evaluation of a mobile wellness application. In: Proceedings of the 6th nordic conference on human–computer interaction. doi:10.1145/1868914.1868920

Emken BA, Li M, Thatte G, Annavaram M, Mitra U, Narayanan S, Sprujit-Metz D (2012) Recognition of physical activities in overweight Hispanic youth using KNOWME networks. J Phys Act Health 9(3):432–441

Chittaro L, Sioni R (2012) Turning the classic snake mobile game into a location-based exergame that encourages walking. In: Proceedings of the 7th international conference on persuasive technology: design for health and safety. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-31037-9_4

Gorgu L, O’Hare GMP, O’Grady MJ (2009) Towards mobile collaborative exergaming. In: Proceedings of the second international conference on advances in human-oriented and personalized mechanisms, technologies, and services. doi:10.1109/CENTRIC.2009.16.61

Bentley F, Tollmar K, Viedma C (2012) Personal health mahsups: mining significant observations from wellbeing data and context. In Proceedings of CHI 2012

Tollmar K, Bentley F, Viedma C (2012) Mobile health mashups: making sense of multiple streams of wellbeing and contextual data for presentation on a mobile device. In: Proceedings of 6th international conference on pervasive computing technologies for healthcare and workshops. doi:10.4108/icst.pervasivehealth.2012.248698

Khan DU, Ananthanarayan S, Le A, Schaefbauer CL, Siek KA (2012) Designing mobile snack application for low socioeconomic status families. In: Proceedings of the 6th international conference on pervasive computing technologies for health care. doi:10.4108/icst.pervasivehealth.2012.248692

Buttusi F, Chittaro L (2010) Smarter phones for healthier lifestyle: an adaptive fitness game. Pervasive Comput 9(4):51–57. doi:10.1109/MPRV.2010.52

Buttusi F, Chittaro L, Nadalutti, D (2006) Bringing mobile guides and fitness activities together: a solution based on an embodied virtual trainer. In: Proceedings of the 8th conference on human–computer interaction with mobile devices and services. doi:10.1145/1152215.1152222

Buttusi F, Chittaro L (2008) MOPET: a context-aware and user-adaptive wearable system for fitness training. Artif Intell Med 42(2):153–163. doi:10.1016/j.artmed.2007.11.004

Lin Y, Jessurun J, de Vries B, Timmermans H (2011a) Motivate: context aware mobile application for activity recommendation. In: Proceedings of the 2nd international conference on ambient intelligence. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-25167-2_27

Lin Y, Jessurun J, de Vries B, Timmermans H (2011b) Motivate: towards context aware recommendation mobile system for healthy living. In: Proceedings of the 5th international conference on pervasive computing technologies for healthcare and workshops. doi:10.4108/icst.pervasivehealth.2011.246030

Bielik P, Tomlein M, Kratky S, Barla M, Bielikova M (2012) Move2Play: an innovative approach to encouraging people to be more physically active. In: Proceedings of the 2nd ACM SIGHIT international health informatics symposium. doi:10.1145/2110363.2110374

Fukuoka Y, Lindgren T, Jong S (2012) Qualitative exploration of the acceptability of a mobile phone and pedometer-based physical activity program in a diverse sample of sedentary women. Public Health Nurs 29(3):232–240. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1446.2011.00997

Fukuoka Y, Komatsu J, Suarez L, Vittinghoff E, Haskell W, Noorishad T, Pham K (2011) The mPED randomised controlled clinical trial: applying mobile persuasive technologies to increase physical activity in sedentary women protocol. BMC Public Health 11:933. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-933

Fujiki Y, Starren J, Kazakos K, Pavlidis I, Puri C, Levine J (2007) NEAT-o-games: ubiquitous activity-based gaming. In: Proceedings of CHI 2007. doi:10.1145/1240866.1241009

Fujiki Y, Kazakos K, Puri C, Buddharaju P, Pavlidia I, Levine J (2008) NEAT-o-games: blending physical activity and fun in the daily routine. ACM Comput Entertain. 6(1). doi:10.1145/1371216.1371224

Kazakos K, Fujiki Y, Pavlidis I, Bourlai T, Levine J (2008) NEAT-o-games: novel mobile gaming versus modern sedentary lifestyle. In: Proceedings of MobileHCI 2008. doi:10.1145/1409240.1409333

Grimes A, Kantroo V, Grinter RE (2010) Let’s play!: mobile health games for adults. In: Proceedings of the 12th ACM international conference on ubiquitous computing. doi:10.1145/1864349.1864370

Grimes A, Grinter R (2007) Designing persuasion: health technology for low-income african american communities. In: Proceedings of the 2nd international conference on persuasive technology

van Gils M, Parkka J, Lappalainen R, Ahonen A, Maukonen A, Tuomisto T (2001) Feasibility and user acceptance of a personal weight management system based on ubiquitous computing. In: Proceedings of the 23rd annual IEEE international conference on engineering in medicine and biology society. doi:10.1109/IEMBS.2001.1019626

Parkka J, van Gils M, Tuomisto T (2000) A wireless wellness monitor for personal weight management. In Proceedings of 2000 IEEE engineering in medicine and biology society

Lee G, Raab F, Tsai C, Patrick K, Griswold WG (2007) PmEB: a mobile phone application for monitoring caloric balance. In: Proceedings of CHI 2006. doi:10.1007/s11036-007-0014-4

Tsai CC, Lee G, Raab F, Norman GJ, Sohn T, Griswold WG, Patrick K (2007) Usability and feasibility of PmEB: a mobile phone application for monitoring real time caloric balance. Mob Netw Appl 12:173–184. doi:10.1007/s11036-007-0014-4

Berkovsky S, Freyne J, Coombe M (2012) Physical activity motivating games: be active and get your own reward. J ACM Trans Comput Hum Interact 19(4). doi:10.1145/2395131.2395139

Rodrigues JJ, Lopes IM, Silva BM, Torre ID (2012) A new mobile ubiquitous computing application to control obesity: SapoFit. Inf Health Soc Care. doi:10.3109/17538157.2012.674586

Silva BM, Lopes IM, Rodrigues JJ, Ray P (2011) SapoFitness: a mobile health application for dietary evaluation. In: Proceedings of 18th international conference on e-health networking, applications and services

Maitland J, Sherwood S, Barkhuus L, Anderson I, Hall M, Brown B, Chalmers M, Muller M (2006) Increasing the awareness of daily levels with pervasive computing. In: Proceedings of pervasive health conference and workshop. doi:10.1109/PCTHEALTH.2006.361667

Anderson I, Maitland J, Sherwood S, Barkhuus L, Chalmers M, Hall M, Brown B, Muller H (2007) Shakra: tracking and sharing daily activity levels with unaugmented mobile phones. Mob Netw Appl 12:185–199

Kuehn E, Sieck, J (2010) Location and situation based services for pervasive adventure games. In: Proceedings of 12th international conference on computer modelling and simulation. doi:10.1109/UKSIM

Kuehn E, Sieck J (2009) Design and implementation of location and situation based services for a pervasive mobile adventure game. In: Proceedings of IEEE international workshop on intelligent data acquisition and advanced computing systems: technology and applications. doi:10.1109/2010.95UKSIM

Reed AA, Samuel B, Sullivan A, Grant R, Grow A, Lazaro J, Mahal J, Kurniawan S, Walker M, Wardrip-Fruin N (2011a) SpyFeet: an exercise RPG. In: Proceedings of the 6th international conference on the foundation of digital games

Reed A A, Samuel B, Sullivan A, Grant R, Grow A, Lazaro J, Mahal J, Kurniawan S, Walker M, Wardrip-Fruin N (2011b) A step towards the future of role-playing games: The SpyFeet mobile {RPG} project. In: Proceedings of the 7th annual international artificial intelligence and interactive digital entertainment conference

Khalil A, Glal S (2009) StepUp: a step counter mobile application to promote healthy lifestyle. In: Proceedings of the 2009 international conference on the current trends in information technology. doi:10.1109/CTIT.2009.5423113

Zhu F, Bosch M, Boushey C J, Delp E J (2010) An image analysis system for dietary assessment and evaluation. In: Proceedings of 2010 IEEE 17th international conference on image processing. doi:10.1109/ICIP.2010.5650848

Khanna N, Boushey CJ, Kerr D, Okos M, Ebert DS, Delp EJ (2010) An overview of the technology assisted dietary assessment project at Purdue University. In: Proceedings of 2010 IEEE international symposium on multimedia. doi:10.1109/ISM.2010.50

Six BL, Tusarebeca ES, Fengqing Z, Mariappan A, Bosch M, Delp EJ, Ebert DS, Kerr DA, Houshey CJ (2010) Evidence-based development of a mobile telephone food record. J Am Diet Assoc 110:74–79. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2009.10.010

Pollak JP, Gay G, Bryne S, Wagner W, Retelny D, Humphreys L (2010) It’s time to eat! Using mobile games to promote healthy eating. Pervasive Comput 9(3):21–27. doi:10.1109/MPRV.2010.41

Bryne S, Gay G, Pollack JP, Gonzales A, Retelny D, Lee T, Wansink B (2012) Caring for mobile phone-based virtual pets can influence youth eating behaviours. J Child Media 6(1):83–99. doi:10.1080/17482798.2011.633410

Oliveira R, Oliver N (2008) TripleBeat: enhancing exercise performance with persuasion. In: Proceedings of MobileHCI 2008. doi:10.1145/1409240.1409268

Consolvo S, McDonald DW, Toscos T, Chen MY, Froehlich J, Harrison B, Klasnja P, LaMarc A, LeGrand L, Libby R, Smith I, Landay JA (2008a) Activity sensing in the wild: a field trial of UbiFit garden. In: Proceedings of CHI 2008. doi:10.1145/1357054.1357335

Consolvo S, Klasnja P, McDonald DW, Avrahami D, Froehlich J, LeGrand L, Mosher K, Landay JA (2008b) Flowers or a robot army? Encouraging awareness and activity with personal, mobile displays. In: Proceedings of the 10th international conference on ubiquitous computing. doi:10.1145/1409635.1409644

Consolvo S, Klasnja P, McDonald DW, Landay JA (2009a) Goal-setting considerations for persuasive technologies that encourage physical activity. In: Proceedings of the international conference on persuasive technology. doi:10.1145/1541948.1541960

Consolvo S, McDonald DW, Landay JA (2009b) Theory-driven design strategies for technologies that support behaviour change in everyday life. In: Proceedings of the 27th international conference on human factors in computing systems. doi:10.1145/1518701.1518766

Klasnja P, Consolvo S, McDonald, DW, Landay JA, Pratt W (2009a) Using mobile and personal sensing technologies to support health behaviour change in everyday life: lessons learned. In: Proceedings of the annual conference of the American medical informatics association. doi:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20351876

Hamilton I, Imperatore G, Dunlop M, Rowe D, Hewitt A(2012) Walk2Build : a GPS game for mobile exergaming with city visualization. In: Proceedings of MobileHCI 2012

Freyne J, Bhandari D, Shlomo B, Borlyse L, Campbell C, Chau S (2010) Mobile mentor: weight management platform. In: Proceedings of the 15th international conference on intelligent user interface. doi:10.1145/1719970.1720046

Freyne J, Brindal E, Hendrie G, Berkovsky S, Coombe M (2012) Mobile applications to support dietary change: highlighting the importance of evaluation context. In: Proceedings of human factors in computing systems CHI EA. doi:10.1145/2212776.2223709

Mattila E, Parkka J, Hermersdorf M, Kaasinen J, Vainio J, Samposalo K, Merilahti J, Kolari J, Kulju M, Lappalainen R, Korhonen I (2008) Mobile diary for wellness management-results on usage and usability in two user studies. IEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed 12(4):501–511. doi:10.1109/TITB.2007.908237

Mattila E (2010) Design and evaluation of a mobile phone diary for personal health management. Doctoral Thesis, VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland

Mattila E, Lappalainen R, Parkka J, Salminen J, Korhonen I (2010) Use of a a mobile phone diary for observing weight management and related behaviours. J Telemed Telecare 16(5):260–264. doi:10.1258/jtt.2009.091103

Mattila E, Korhonen I, Salminen J, Ahtinen A, Koskinen E, Sarela A, Parlka J, Lappalainen R (2010) Empowering citizens for well-being and chronic disease management with wellness diary. IEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed 14(2):456–463. doi:10.1109/TITB.2009.2037751

Chuah M, Jakes G, Qin Z (2012) WifiTreasureHunt: a mobile social application for staying active physically. In: Proceedings of the 2012 ACM conference on ubiquitous computing. doi:10.1145/2370216.2370339

Intille SS, Albinali F, Mota S, Kuris B, Botana P, Haskell WL (2011) Design of a wearable physical activity monitoring system using mobile phones and accelerometers. In: Proceedings of the 33rd annual international conference of the IEEE engineering in medicine and biology society. doi:10.1109/IEMBS.2011.6090611

Doran K, Pickford S, Austin C, Walker T, Barnes T (2010) World of workout: towards pervasive intrinsically motivated, mobile exergaming. In: Proceedings of meaningful play

Gerrig RJ (1993) Experiencing narrative worlds: on the psychological activities of reading. Yale University Press, New Haven

Green MC, Brock TC (2000) The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. J Pers Soc Psychol 79(5):701–721. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.701

Weinstein ND, Sandman PM (1992) A model of the precaution adoption process: evidence from home radon testing. Health Psychol 1193:170–180. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.11.3.170

Bandura A (1986) Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs

Hassenzahl M, Burmester M, Koller F (2003) AttrakDiff: questionnaire to measure perceived hedonic and pragmatic quality. In: Ziegler J, Szwillus G (ed) Mensch and Computer 2003: Interaktion in Bewegung, pp 187–196

van den Berg MH, Schoones JW, Vlieland TPMV (2007) Internet-based physical activity interventions: a systematic review of the literature. J Med Internet Res 9(3). doi:10.2196/jmir.9.3.e26

Whiteley JA, Bailey BW, McInnis KJ (2008) State of the art reviews: Using the internet to promote physical activity and healthy eating in youth. Am J Lifestyle Med 2. doi:10.1177/1559827607311787

Arem H, Irwin M (2010) A review of web-based weight loss interventions in adults. Obes Manag 787:236–243

Mitchell WL, Economou D, Randall D (2000) God is an alien: understanding informant responses through user participation and observation. In: Proceedings of PDC2000 6th biennial participatory design conference

Scaife M, Rogers Y, Aldrich F, Davies M (1997) Designing for or designing with? Informant design for interactive learning environments. In: Proceedings of CHI ‘97: human factors in computing systems

Nielsen J (1994) Heuristic evaluation. In: Nielsen J, Mack RL (eds) Usability inspection methods. Wiley, New York

Lewis C, Wharton C (1997) Cognitive walkthroughs. In: Helander M (ed) A guide to human factors and ergonomics. CRC Press, USA

Noar SM, Harrington NG, Van Stee SKV, Aldrich RS (2011) Tailored health communication to change lifestyle behaviours. Am J Lifestyle Med 5:112–122. doi:10.1177/1559827610387255

Krebs P, Prochaska JO, Rossi JS (2010) A meta-analysis of computer-tailored interventions for health behaviour change. Prev Med 51:214–221. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.06.004

Prochaska J, Velicer W (1997) The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot 12(1):38–48

Duncan S (2005) Sources and types of social support in youth physical activity. Health Psychol 24:3–10. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.24.1.3

Voorhees CC, Murray D, Welk G, Birnbaum A, Ribisl KM, Johnson CC, Pfeiffer KA, Saksvig B, Jobe JB (2005) Role of peer social network factors and physical activity in adolescent girls. Am J Health Behav 29:183–190. doi:10.5993/AJHB.29.2.9

Consolvo, S., Everitt, K., Smith, I., Landay, J. A., 2006. Design requirements for technologies that encourage physical activity. In: Proceedings of CHI 2006

Klasnja P, Consolvo S, Choudhury T, Beckwith R, Hightower J (2009b) Exploring privacy concerns about personal sensing. In: Proceedings of the 7th international conference on pervasive putting. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-01516-8_13

Mutsuddi AU, Connelly K (2012) Text messages for encouraging physical activity: are they effective after the novelty effect wears off?. In: Proceedings of the 6th international conference on pervasive computing technologies for healthcare (Pervasive Health) and workshops. doi:10.4108/icst.pervasivehealth.2012.248715

Fogg BJ (2003) Persuasive technology: using computers to change what we think and do (interactive technologies). Morgan Kaufmann, Masssachusetts

Lenert L, Norman GJ, Mailhot M, Patrick K (2005) A framework for modeling health behavior protocols and their linkage to behavioural theory. J Biomed Inform 38:270–280. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2004.12.001

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: A brief overview of mobile phones applications that were included in the review

Underlying design concept | Targeted users | Role | Aim | Description of application | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1. | Self-awareness | Not explicitly specified | Tracking | Increasing physical activity | A context-aware mobile application that is based on recognition of movement and location capable to enable estimation and evaluation of the user’s activity all day long | |

2. | Self-awareness and social goal setting | Individual with sedentary life style | Enforcing social influence | Increasing physical activities | Users share goals by proposing physical activity challenges to others. Accepted physical activity challenge becomes new goal, and recorded physical activities are shared among users | |

3. | Theory of planned behaviour, theory of meaning behaviour and personality theory | Teenagers | Entertainment | Increasing physical activity | Users’ personalities are identified and used to determine set of games relevant to their personalities. Motivational agent provides encouragement and positive reinforcement. User recorded manually the duration spent to play game | |

4. | Not indicated | Not explicitly specified | Tracking | Monitoring lifestyle | Users are provided with real-time feedback of their caloric intake/expenditure balance throughout the day by capturing their caloric intake through manual entries of food diaries and caloric expenditure through automatic detection of physical activity | |

5. | Goal setting, self-monitoring, positive reinforcement and social support | Teenage girls | Enforcing social influence | Increasing physical activity | Providing a group support system to promote walking towards a self-established daily step goals. Users entered step counts and shared them within the group with text message notification of step updates. Users can send motivating text messages to all or individual members of the group | |

6. | Not indicated | Adolescents | Entertainment | Increasing physical activity | A suite of three different game applications to promote physical activities utilising accelerometer | |

7. | Not indicated | Children and adolescent obesity and overweight | Tracking | Automatic recording of food and physical activity | Users’ physical activities are recorded automatically through motion sensors. Users recorded their food intake by taking photos of each meat at the beginning which are later analysed manually by nutritionist | |

8. | Not indicated | Not explicitly specified | Tracking | Automatic recording of food intake | Users are able to automatically calculate and log the caloric content of over nine thousand types of food, through the use a laser grid and a camera equipped mobile phone. Users are allowed to view an up-to-date summary of their daily eating habits | |

9. | DietCam [39] | Not indicated | Not explicitly specified | Tracking | Automatic recording of food intake | Users take three images or a short video of the meal (prior and after the meal). Images/videos are then used to recognise, classify and estimate the volume and calorie content of the meal |

10. | DiTS [40] | Not indicated | Children with obesity | Entertainment | Increasing physical activity | A mobile phone version of the popular arcade game on dancing. Users worn 3-axis accelerometers that are worn around the players’ ankles which record their legs movement with mobile phones to control the game and to display graphics |

11. | ExerTrek [41] | Not indicated | Not explicitly specified | Tracking | Optimising physical activity’s benefit | An exercise monitor on the mobile phone that will help an individual achieve a certain goal that users want from doing exercise. Once the goals and personal information are set for the individuals, it advises users to achieve the maximal benefits of their exercise without going beyond their own limits |

12. | Not indicated | Not explicitly specified | Entertainment | Increasing outdoor physical activity | An application platform to support physical outdoor exercise. It utilises location information and a mobile phone acts as a terminal device for the game | |

13. | Fitness tour [44] | Not indicated | School children and college students | Entertainment | To increase physical activity | Users are assigned an exercise tour, containing several locations, and shared their achievement through social media. Users’ verification are required at each location. Users’ heart beat were recorded at the start and end of the tour through a mobile phone’s camera |

14. | Not indicated | Not explicitly specified | Tracking | Automatic recording of food intake | Users take photos of their food intake which are then analysed to estimate the nutritional composition of the meals. The food images and their calorie content are stored in a database and accessible to users who can also revise the calorie information | |

15. | Food fight [47] | Not indicated | Adult | Entertainment | Education in nutrition and healthy eating | Introducing competition between users through comparisons of their diets and the rating of their diet |

16. | Persuasive design | Not explicitly specified | Entertainment | Increasing physical activity | Users are required to make certain physical movement while wearing accelerometer as the primary game mechanic | |

17. | HealthAware [50] | Not indicated | Not explicitly specified | Tracking | Monitoring lifestyle | Users monitor daily physical activity through embedded accelerometer and analyse food item by capturing food image with camera. Users are presented with activity counts at real time |

18. | Persuasive design | Individuals with obesity | Enforcing social influence | Increasing physical activity | Users are encouraged to perform physical activity by sharing step count with friends | |

19. | HyperFit [53] | Not indicated | Individuals with overweight issue | Tracking | Mimic personal nutrition counselling | Users are provided with self-evaluation tools for testing and goal definition, food and exercise diaries, analysis tools, and feedback and encouragement given by a virtual trainer |

20. | Not indicated | Adolescents | Entertainment | To increase physical activity | Users’ real world physical movement is used to control their virtual character, interact with Non-Player Character, visit landmarks and collect game items | |

21. | Impact [56] | Self-awareness | People with sedentary life style | Tracking | Monitoring physical activities | Users can capture number of steps, manually input the context of activities and review them on a web |

22. | Into [57] | Not indicated | Not explicitly specified | Tracking | To increase physical activity | The number of steps of a user, automatically recorded by in-built pedometer in a phone, is used to “proceed” (travel virtually) on a map. A use can play as an individual or a member of team |

23. | KnowME [58] | Not indicated | Overweight youth | Tracking | Monitoring physical activities | Users’ biometric signals of users are monitored and visualising users’ level of physical activity and sedentary behaviour |

24. | LocoSnake [59] | Not indicated | Not explicitly specified | Entertainment | To increase physical activity | A player embodies the snake and walks in the physical world to control it and get points |

25. | Luften [60] | Not indicated | Children with obesity or overweight issues | Entertainment | Increasing physical activity | Players are encouraged to move between the different zones through defined routes as their objectives of the game |

26. | Not indicated | Not explicitly specified | Tracking | Monitoring lifestyle | Users are provided with a mobile service that collects data from a variety of health and well-being sensors and presented significant correlations across sensors in a mobile widget as well as on a mobile web application | |

27. | Mobile snack [63] | Social cognitive theory, health belief model, elaboration likelihood model, transportation theory and the precaution adoption process model | Low socioeconomic status families | Tracking | Monitoring food intake | Users are provided with features to input and monitor snacking behaviour and receive feedback on snack healthiness |

28. | Monster and Gold [64] | Not indicated | People with sedentary life style | Entertainment | Trains and motivate users to jog outdoors | Users are provided with a context-aware and user-adaptive game which takes into account their heart rate, age, fitness level, and exercise phase |

29. | Not indicated | Not explicitly specified | Advisory | Trains and motivate users to jog and perform exercise outdoors | User’s positions during physical activity in an outdoor fitness trail are monitored to provide navigation assistance by using a fitness trail map and giving speech directions. An embodied virtual trainer shows how to correctly perform the exercises along the trail with 3D animations | |

30. | Persuasive design | Not explicitly specified | Advisory | Physical activity recommendation | Provides users with and contextualized advice on possible physical activities to do | |

31. | Move2PlayKids [69] | Goal setting, Self-awareness | Children aged 10–18 | Tracking | To increase physical activity | Users’ number of steps is obtained and their activities are inferred through GPS |

32. | Not indicated | Sedentary women | Tracking | Increasing physical activity | The mobile phone serves as a means of delivering the physical activity intervention, setting individualized weekly physical activity goals, and providing self-monitoring (activity diary), immediate feedback and social support. The mobile phone also functions as a tool for communication and real-time data capture | |

33. | Not indicated | Not explicitly specified | Entertainment | Increasing physical activity | Users physical activity are monitored and their level of activities control the animation of their avatars in a virtual race game with other players over the cellular network. Winners are declared every day and players with an excess of activity points are given rewards | |

34. | Transtheoretical model | African American adults in the South-eastern US | Entertainment | Educate nutrition and healthy eating | Users learn how to make healthier meal choices by ordering healthy menu in the game | |

35. | Not indicated | Not explicitly specified | Tracking | Self-monitoring system | Providing a self-monitoring and expert guidance system on physical activities and calorie intakes | |

36. | Self-awareness | Overweight and obese adults | Tracking | Weight management | Users track their caloric balance by recording food intake and physical activity on their mobile phones. Daily reminder messages are also sent via SMS messages to encourage compliance | |

37. | Run, tradie, run [81] | Persuasive design | Not explicitly specified | Entertainment | To increase physical activity | A player can purchase the in-game commodities using points that are earned by performing real physical activity |

38. | Not indicated | Not explicitly specified | Enforcing social influence | Dietetic monitoring and assessment | Users keep daily Personal Health Record (PHR) of their food intake and daily exercise, and to share them with a social network. | |

39. | Transtheoretical model and Social Cognitive Theory | Adult | Enforcing social influence | Increasing physical activity | Users physical activities are tracked through the fluctuation signal strength of their mobile phone and the results are shared with their peer | |

40. | Not indicated | Adolescent girls | Entertainment | To increase physical activity | Promoting physical fitness through addiction to an ongoing and compelling episodic interactive story whose progression is tied to exercise activities | |

41. | Not indicated | Not explicitly specified | Entertainment | Increasing physical activity | Users are encouraged to perform physical activity by solving quests and performing sports | |

42. | StepUp [90] | Not indicated | UAE population | Tracking | Increasing physical activity | It provides sensor-enabled mobile phones to automatically infer the number of steps the user walked and give the user a quantitative measure of his or her daily activities |

43. | Not indicated | Not explicitly specified | Tracking | Automatic recording of food intake | Users take mages of the meal which are then used to recognise, classify and estimate the volume and calorie content of the meal | |

44. | Persuasive design | Children | Entertainment | To motivate healthy eating practice | Users learn about healthy eating by sending photos of the food they consumed to their virtual pet | |

45. | Triple beat [96] | Persuasive design | Runners | Entertainment | To optimise physical activity | assists runners in achieving predefined exercise goals via musical feedback and two persuasive techniques: a glanceable interface for increased personal awareness and a virtual competition |

46. | Goal-setting, Transtheoretical Model of Behaviour Change | Not explicitly specified | Tracking | To increase physical activity | Users can journal and review their physical activities and are shown abstract glanceable display of their physical activities each week on their phone’s background screen | |

47. | Not indicated | Individuals engaged in a weight lost program (meal replacement) | Tracking | Monitoring food intake and weight data | A user is proactively prompted and reminded to interact with the application & initiate health and self-monitoring related tasks | |

48. | Walk2Build [104] | Social participation | Not explicitly specified | Entertainment | To increase physical activity | Recorded GPS data and distance travelled are converted into steps and submitted to a server to create a city which can then be shared with other users |

49. | CBT-based self-management | Not explicitly specified | Tracking | Monitoring lifestyle | Users can journal and review their lifestyle (weight, level of exercise, food intake, etc.) | |

50. | WiFi treasure hunt [109] | Not indicated | School children and college students | Entertainment | To increase physical activity | A user is assigned with a random running tour consisting 10 locations with tree of the selected locations will have “hidden treasures” |

51. | Wockets [110] | Not indicated | Not explicitly specified | Tracking | Monitoring physical activities | Capturing raw motion data to discriminate between activity types or to more accurately estimate energy expenditure |

52. | World of workout [111] | Not indicated | College students and gamers | Entertainment | To increase physical activity | A user levels up by working towards their goals and completing quests by achieving required number of steps |

Appendix 2: A detailed review of mobile phone applications from UCD perspective

Final outcome of studies | UCD key principles | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Understanding of users, tasks and environment | User involvement throughout design and development | Design was driven and refined by user-centred evaluation | Iterative design process | Addressing the whole user experience | Inclusion of multidisciplinary skills and perspective | |||

1. | Fully functioning prototype | Not indicated | Not indicated | Not indicated | Not indicated | Not indicated | Yes | |

2. | Limited functioning prototype | User interviews with limited number of users (despite broad definition of users) for concept development | Users were involved in design concept refinement and evaluation of prototype. Methods adopted were low-fidelity prototyping, video prototyping, interviews and focus group | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

3. | Fully functioning prototype | Survey and focus group were performed for targeted end-users | Users were involved in concept development and evaluation of prototype | Not indicated | Not indicated | Yes | Yes | |

4. | Fully functioning prototype | Not indicated | Users were involved to validate automatic recognition of physical activities as well as design refinement for food diary (focus groups) | Yes | Yes | Not applicable | Yes | |

5. | Fully functioning prototype | Informal interviews with dietitian; followed by exploratory field interviews and ethnography with targeted end-user | Users were involved in design concept refinement and evaluation of prototype. Methods adopted were low- and high-fidelity prototyping, interviews and questionnaires | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

6. | Fully functioning prototype | Scenarios were used to explore context of use but no users were involved | Plan to involve user to evaluate high-fidelity prototype | Not indicated | Not indicated | Not applicable | Not indicated | |

7. | Fully functioning prototype | Not indicated | Users were only involved to validate automatic recognition of physical activities | Not indicated | Not indicated | Not indicated | Not indicated | |

8. | Fully functioning prototype | Not indicated | Not indicated | Not indicated | Not indicated | Not indicated | Not indicated | |

9. | DietCam [39] | Fully functioning prototype | Not indicated | Not indicated | Not indicated | Not indicated | Not indicated | Not indicated |

10. | DiTS [40] | Fully functioning prototype | Not indicated | Users were involved in the evaluation of high-fidelity prototype | Not indicated | Not indicated | Yes | Yes |

11. | ExerTrek [41] | Fully functioning prototype | Not indicated | Users were only involved in the evaluation of prototype | Not indicated | Not indicated | Not indicated | Yes |

12. | Fully functioning prototype | Extensive user studies were performed for concept development | Users were involved in design concept refinement and evaluation of prototype. Methods adopted were low- and high-fidelity prototyping, focus groups interviews and questionnaires | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

13. | Fitness tour [44] | Fully functioning prototype | Not indicated | Users are planned to be involved in the evaluation of the application | Not indicated | Not indicated | Not indicated | Not indicated |

14. | Fully functioning prototype | Not indicated | Not indicated | Not indicated | Not indicated | Not indicated | Not indicated | |

15. | Food fight [47] | Fully functioning prototype | Interviews were conducted with targeted end-users and stakeholders | Users were involved in design concept refinement and evaluation of prototype. Methods adopted were low- and high-fidelity prototyping and interviews | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

16. | Fully functioning prototype | Not indicated | Users were involved in the evaluation of early prototype | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

17. | HealthAware [50] | Fully functioning prototype | Not indicated | Users were involved to validate automatic recognition of physical activities and a really limited user interface evaluation. | Not indicated | Not indicated | Not indicated | Not indicated |

18. | Fully functioning prototype | Not indicated | Users were involved to validate functions of the prototype | Not indicated | Not indicated | Yes | Yes | |

19. | HyperFit [53] | Fully functioning prototype | Consumer survey and interviews with stakeholders | Users and stakeholders were involved in design concept refinement and evaluation of prototype | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

20. | Fully functioning prototype | End-users and expert interview were performed | Users were involved in concept development and evaluation of prototype | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

21. | Impact [56] | Fully functioning prototype | End-users studies were performed to establish system features | Users were involved in concept development and evaluation of prototype | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

22. | Into [57] | Fully functioning prototype | End-users studies were performed to refine the concept and design aspects | Users were involved in concept development and evaluation of prototype | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

23. | KnowME [58] | Fully functioning prototype | Not indicated | Users were only involved to validate energy expenditure capturing | Not indicated | Not indicated | Not indicated | Not indicated |