Abstract

We investigated the incidence of disability and its risk factors in older Japanese adults to establish an evidence-based disability prevention strategy for this population. For this purpose, we used data from the Longitudinal Cohorts of Motor System Organ (LOCOMO) study, initiated in 2008 to integrate information from cohorts in nine communities across Japan: Tokyo (two regions), Wakayama (two regions), Hiroshima, Niigata, Mie, Akita, and Gunma prefectures. We examined the annual occurrence of disability from 8,454 individuals (2,705 men and 5,749 women) aged ≥65 years. The estimated incidence of disability was 3.58/100 person-years (p-y) (men: 3.17/100 p-y; women: 3.78/100 p-y). To determine factors associated with disability, Cox’s proportional hazard model was used, with the occurrence of disability as an objective variable and age (+1 year), gender (vs. women), body build (0: normal/overweight range, BMI 18.5–27.5 kg/m2; 1: emaciation, BMI <18.5 kg/m2; 2: obesity, BMI >27.5 kg/m2), and regional differences (0: rural areas including Wakayama, Niigata, Mie, Akita, and Gunma vs. 1: urban areas including Tokyo and Hiroshima) as explanatory variables. Age, body build, and regional difference significantly influenced the occurrence of disability (age, +1 year: hazard ratio 1.13, 95 % confidence interval 1.12–1.15, p < 0.001; body build, vs. emaciation: 1.24, 1.01–1.53, p = 0.041; body build, vs. obesity: 1.36, 1.08–1.71, p = 0.009; residence, vs. living in rural areas: 1.59, 1.37–1.85, p < 0.001). We concluded that higher age, both emaciation and obesity, and living in rural areas would be risk factors for the occurrence of disability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In Japan, the proportion of the population aged 65 years or older has increased rapidly over the years. In 1950, 1985, 2005, and 2010, this proportion was 4.9, 10.3, 19.9, and 23.0 %, respectively [1]. Further, this proportion is estimated to reach 30.1 % in 2024 and 39.0 % in 2051 [2]. The rapid aging of Japanese society, unprecedented in world history, has led to an increase in the number of disabled elderly individuals requiring support or long-term care. The Japanese government initiated the national long-term care insurance system in April 2000 in adherence with the Long-Term Care Insurance Act [3]. The aim of the national long-term care insurance system was to certify the level of care needed by elderly adults and to provide suitable care services to them according to the levels of their long-term care needs. According to the recent National Livelihood Survey by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare in Japan, the number of elderly individuals certified as needing care services increases annually, having reached 5 million in 2011 [4].

However, few prospective, longitudinal, and cross-national studies have been carried out to inform the development of a prevention strategy against disability. To establish evidence-based prevention strategies, it is critically important to accumulate epidemiologic evidence, including the incidence of disability, and identify its risk factors. However, few studies have attempted to estimate the incidence of the disability and its risk factors by using population-based cohorts. In addition, to identify the incidence of disability, a study should have a large number of subjects. Further, to determine regional differences in epidemiological indices, a survey of cohorts across Japan is required.

The Longitudinal Cohorts of Motor System Organ (LOCOMO) study was initiated in 2008, through a grant from Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, for the prevention of knee pain, back pain, bone fractures, and subsequent disability. It aimed to integrate data gathered from cohorts from 2000 onwards and follow-up surveys from 2006 onwards, using a unified questionnaire, with an ultimate goal being the prevention of musculoskeletal diseases. The present study specifically aims at using LOCOMO data, which is based on the long-term care insurance system, to investigate the occurrence of disability in order to clarify its incidence and risk factors, especially in terms of body build and regional differences.

Materials and methods

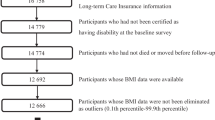

Participants were residents of nine communities located in Tokyo (two regions: Tokyo-1, principal investigators (PIs): Shigeyuki Muraki, Toru Akune, Noriko Yoshimura, Kozo Nakamura; Tokyo-2, PIs: Yoko Shimizu, Hideyo Yoshida, Takao Suzuki), Wakayama [two regions: Wakayama-1 (mountainous region) and Wakayama-2 (coastal region), PIs: Noriko Yoshimura, Munehito Yoshida], Hiroshima (PI: Saeko Fujiwara), Niigata (PI: Go Omori), Mie (PI: Akihiro Sudo), Akita (PI: Hideyo Yoshida), and Gunma (PI: Yuji Nishiwaki) prefectures [5]. Figure 1 shows the location of each cohort in Japan.

Disability in the present study was defined as ‘cases requiring long-term care’, as determined by the long-term care insurance system. The procedure for identifying these cases is as follows: (1) each municipality establishes a long-term care approval board consisting of clinical experts, physicians, and specialists at the Division of Health and Welfare in each municipal office; (2) The long-term care approval board investigates the insured person by using an interviewer-administered questionnaire consisting of 82 items regarding mental and physical conditions, and makes a screening judgement based on the opinion of a regular doctor; (3) ‘Cases requiring long-term care’ are determined according to standards for long-term care certification that are uniformly and objectively applied nationwide [6].

In order to identify the incidence of disability, data were collected from participants aged 65 years and older within the above-mentioned cohorts. In Japan, most individuals certified as ‘cases requiring long-term care’ are 65 years and older. Table 1 shows the number of subjects per region, as well as the data obtained within the first year of the observation. The smallest cohort consisted of 239 subjects, residing in Mie, while the largest consisted of 1,758, who resided in Gunma.

The earliest baseline data were collected in 2000 in Hiroshima, while the latest were obtained in 2008 in Tokyo-2. The cohorts were subsequently followed until 2012. Data regarding participants’ deaths, changes of residence, and occurrence or non-occurrence of certified disability were gathered annually from public health centres of the participating municipalities. As an index of body build, baseline data on participants’ height and weight were collected, and used to calculate body mass index (BMI, kg/m2). Participants were classified as follows: normal or overweight (BMI = 18.5–27.5), obese (BMI >27.5), or emaciated (BMI <18.5). These cut-off points were determined according to a WHO report [7]. From 2008 onwards, follow-up data was obtained using the unified questionnaire.

All participants provided written informed consent, and the study was conducted with the approval of the ethics committees of the University of Tokyo (nos. 1264 and 1326), the Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology (no. 5), Wakayama (no. 373), the Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RP 03-89), Niigata University (no. 446), Mie University (nos. 837 and 139), Keio University (no. 16–20), and the National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology (no. 249). Careful consideration was given to ensure the safety of the participants during all of the study procedures.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using STATA (STATA Corp., College Station, Texas, USA). Differences in proportions were compared using the chi-squared test. Differences in continuous variables were tested using an analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Scheffe’s least significant difference test for post-hoc pairwise comparisons. To test the association between the occurrence of disability and other variables, Cox’s proportional hazard regression analysis was used. Hazard ratios (HRs) were estimated using the occurrence of disability as an objective variable (0: non-occurrence, 1: occurrence) and the following explanatory variables: age (±1 year), gender (vs. female), body build (0: normal and overweight vs. 1: emaciation vs. 2: obesity), and regional differences (0: rural areas, including Wakayama-1, Wakayama-2, Niigata, Mie, Akita, and Gunma vs. 1: urban areas, including Tokyo-1, Tokyo-2, and Hiroshima). All p values and 95 % confidence intervals (CI) of two-sided analyses are presented.

Results

Table 2 shows the number of participants classified by age and gender. The majority of participants were 75–79 years old; two-thirds of the participants were women.

Selected characteristics of the study population, including age, height, weight, and BMI, are shown in Table 3. The mean values of age, height, and weight were significantly greater in women than in men (p < 0.001), but BMI did not significantly differ between men and women (p = 0.479).

The estimated incidence of disability is shown in Fig. 2. In total, the incidence of disability among individuals aged 65 years and older was 3.58/100 person-years (p-y) (p-y; men: 3.17/100 p-y; women: 3.78/100 p-y). The incidence of disability was 0.83/100 p-y, 1.70/100 p-y, 3.00/100 p-y, 6.36/100 p-y, and 13.54/100 p-y in 65–69-, 70–74-, 75–79-, 80–84-, and ≥85-year-old men, respectively. In women, the incidence of disability was 0.71/100 p-y, 1.40/100 p-y, 3.25/100 p-y, 6.85/100 p-y, and 12.01/100 p-y in the age ranges of 65–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84, and 85 or more years, respectively (Table 4).

Cox’s proportional hazard regression analysis showed that occurrence of disability was significantly influenced by age, body build, and regional differences, but not gender (age, +1 years: hazard ratio 1.13, 95 % confidence interval 1.12–1.15, p < 0.001; sex, vs. female: 1.13, 0.97–1.31, p = 0.125; body build: emaciation: 1.24, 1.01–1.53, p = 0.041; body build; obesity: 1.36, 1.08–1.71, p = 0.009; residence, vs. living in rural areas: 1.59, 1.37–1.85, p < 0.001).

Discussion

Using the data of the LOCOMO study, we determined the incidence of disability and identified age, emaciation, obesity, and residence in rural areas as risk factors for the occurrence of disability. More specifically, we integrated data collected from subjects aged 65 and older in individual cohorts established in nine regions across Japan to determine the incidence of disability in the specified regions. We found an association between various risk factors and disability; these include age, emaciation, and obesity, as well as residence in rural areas.

The LOCOMO study was the first nation-wide prospective study to track a large number of the subjects from several population-based cohorts. The LOCOMO study aimed to integrate information from these cohorts, to prevent musculoskeletal diseases and subsequent disability. The data shed light on the prevalence and characteristics of targeted clinical symptoms such as knee pain or lumbar pain, or defined diseases such as knee osteoarthritis (KOA), lumbar spondylosis (LS), and osteoporosis (OP), as well as their prognosis in reference to either mortality or chances of developing a disability. In the present study, we also compared the above-mentioned symptoms, diseases, and prognoses between regions.

The overall incidence of disability among individuals aged 65 years and older was 3.58/100 person-years. When results from the present study are applied to the total age-sex distribution derived from the Japanese census in 2010 [1], it could be assumed that 1,110,000 people (410,000 men and 700,000 women) aged 65 years and older are newly affected by disability and require support. It has been reported that the total number of subjects who were certified as needing care increases annually [4]; however, few of these reports estimate the number of newly certified cases through a population-based cohort. Clarifying the incidence of disability and its risk factors was viewed as the first step toward preventing its occurrence.

Emaciation and obesity were both identified as risk factors for disability; thus, there appears to be a U-shaped association between BMI and disability as well as between BMI and mortality [8, 9]. According to the recent National Livelihood Survey, the leading cause of disabilities that require support and long-term care is cardiovascular disease (CVD), followed by dementia, senility, osteoarthrosis, and fractures [4]. Obesity is an established risk factor for chronic diseases, including hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus, which increase the risk for CVD [10]; in turn, CVD causes ADL-related disabilities in older adults. In addition, numerous reports have shown an association between overweight or obesity and KOA [11–17]. In previous reports, we found a significant association between BMI and not only the presence of KOA, but also the occurrence and progression of KOA [18, 19]. In addition, emaciation is an established risk factor for OP and OP-related fractures [20]. OP might be related to low nutrition due to chronic wasting diseases.

The current study also found an association between living in a rural area and the occurrence of disability. There have been reports of regional differences in the certification rate of disability in Japan. For instance, Kobayashi reported a prefectural difference in the certification rate of disability, which was particularly prominent among individuals aged 75 years and older at lower nursing care levels in the long-term care insurance system [21]. In addition, Shimizutani et al. [22] pointed out that the financial condition of the insurer influenced the certification rate of disability. Further, Nakamura found that the certification of lower care levels was influenced by social and/or individual factors, such as the type of service provider, the application rate, and number of medical treatment recipients. However, certification of advanced nursing care levels was influenced by CVD and lifestyle-related diseases [23].

Other than differences in the social backgrounds of individuals in each prefecture, we posited that regional differences (rural or urban) in the occurrence of disability might be due to differences in the frequency of diseases and ailments that cause disability in each area. The prevalence of musculoskeletal diseases, such as KOA and LS, differs among mountainous, coastal, and urban areas [24]. Evidence also exists for regional differences in the incidence of hip fractures [25–27]. It was also found that mortality and incidence of ischemic stroke, which is related to CVD, was higher in the northeastern than in the southwestern part of Japan [28]. However, there is currently no information on regional differences in dementia prevalence and incidence in Japan. In general, differences in the frequency of diseases causing disability might influence regional differences in disability rates. In relation to this, in a future study on follow-up data from the LOCOMO study, it might be necessary to collect information on the prevalence and frequency of diseases that cause disability, such as musculoskeletal diseases, CVD, and dementia. This future study should also attempt to clarify mutual associations among risk factors for disability, so as to inform the development of measures for its primary prevention.

Despite its contribution to existing knowledge, the present study has several limitations. First, its sample does not truly represent the entire Japanese population, because our cohorts were not drawn from the northernmost and southernmost parts of Japan (e.g., Okinawa prefecture or Hokkaido prefecture). This limitation must be taken into consideration, especially when determining the generalisability of the results. However, the LOCOMO study is the first large-scale, population-based prospective study with approximately 9,000 participants aged 65 years and older. Second, data collected from the cohorts were not uniform, as certain information was obtained from some participants, but not others. For example, the X-ray examinations of subjects’ knees were performed in Tokyo-1, Wakayama-1, Wakayama-2, Niigata, and Mie; lumbar spine X-ray examinations were performed in Tokyo-1, Wakayama-1, Wakayama-2, Hiroshima, and Mie. Therefore, we could not evaluate the presence or absence of KOA, LS, or OP as a possible cause of disability by using the data of the entire LOCOMO study. Further investigation following the integration of information on musculoskeletal disorders would enable us to evaluate all the factors that are associated with disability.

Nevertheless, our study has several strengths. As mentioned above, the large sample size is the study’s biggest strength. The second strength is that we collected data from nine cohorts across Japan, which enabled us to compare regional differences in the incidence of disability. In addition, the variety of measures and assessments used in this study enabled us to collect a substantial amount of detailed information. However, given the fact that not all of the measures were administered in all cohorts, regional selection bias in the analysis should be considered when interpreting the results.

References

Statistical Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication. Population Count based on the 2010 Census Released. http://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/kokusei/pdf/20111026.pdf. Accessed 26 Feb 2014

National Institute of Population and Society Research (2012) Population projections for Japan (January 2012): 2011–2060. http://www.ipss.go.jp/site-ad/index_english/esuikei/ppfj2012.pdf. Accessed 26 Feb 2014

Long-Term Care Insurance Act. http://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/law/detail_main?id=94&vm=4&re=. Accessed 26 Feb 2014

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2010) Outline of the results of National Livelihood Survey. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/k-tyosa/k-tyosa10/4-2.html. Accessed 26 Feb 2014 (in Japanese)

Yoshimura N, Nakamura K, Akune T, Fujiwara S, Shimizu Y, Yoshida H, Omori G, Sudo N, Nishiwaki Y, Yoshida M, Shimokata H (2013) The longitudinal cohorts of motor system organ (LOCOMO) study. Nippon Rinsho 71:642–645 (in Japanese)

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Long-term care insurance in Japan. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/topics/elderly/care/index.html. Accessed 26 Feb 2014

WHO Expert Consultation (2004) Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet 363:157–163

Zheng W, McLerran DF, Rolland B, Zhang X, Inoue M et al (2011) Association between body-mass index and risk of death in more than 1 million Asians. N Engl J Med 364:719–729

Whitlock G, Lewington S, Sherliker P, Clarke R, Emberson J, Halsey J, Qizilbash N, Collins R, Peto R, Prospective Studies Collaboration (2009) Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900,000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. Lancet 373:1083–1096

Haslam DW, James WP (2005) Obesity. Lancet 366:1197–1209

Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Naimark A, Walker WM, Meenan RF (1988) Obesity and knee osteoarthritis: the Framingham study. Ann Intern Med 109:18–24

Hart DJ, Spector TD (1993) The relationship of obesity, fat distribution and osteoarthritis in the general population: the Chingford study. J Rheumatol 20:331–335

Van Saase JL, Vandenbroucke JP, Van Romunde LK, Valkenburg HA (1998) Osteoarthritis and obesity in the general population. A relationship calling for an explanation. J Rheumatol 15:1152–1158

Magliano M (2008) Obesity and arthritis. Menopause Int 14:149–154

Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G, Abramson S, Altman RD, Arden N et al (2008) OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines. Osteoarthr Cartil 16:137–162

Muraki S, Akune T, Oka H, Mabuchi A, En-yo Y, Yoshida M et al (2009) Association of occupational activity with radiographic knee osteoarthritis and lumbar spondylosis in elderly patients of population-based cohorts: a large-scale population-based study. Arthr Rheum 61:779–786

Lohmander LS, Gerhardsson de Verdier M, Rollof J, Nilsson PM, Engstrom G (2009) Incidence of severe knee and hip osteoarthritis in relation to different measures of body mass: a population-based prospective cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis 68:490–496

Yoshimura N, Muraki S, Oka H, Kawaguchi H, Nakamura K, Akune T (2011) Association of knee osteoarthritis with the accumulation of metabolic risk factors such as overweight, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, and impaired glucose tolerance in Japanese men and women: the ROAD study. J Rheumtol 38:921–930

Yoshimura N, Muraki S, Oka H, Tanaka S, Kawaguchi H, Nakamura K, Akune T (2012) Accumulation of metabolic risk factors such as overweight, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, and impaired glucose tolerance raises the risk of occurrence and progression of knee osteoarthritis: a 3-year follow-up of the ROAD study. Osteoarthr Cartil 20:1217–1226

De Laet C, Kanis JA, Odén A, Johanson H, Johnell O, Delmas P, Eisman JA, Kroger H, Fujiwara S, Garnero P, McCloskey EV, Mellstrom D, Melton LJ 3rd, Meunier PJ, Pols HA, Reeve J, Silman A, Tenenhouse A (2005) Body mass index as a predictor of fracture risk: a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 16:1330–1338

Kobayashi T (2011) The relationship between variation in the requirement certification rate in prefectures and nursing care level in long-term care insurance. Otsuma Women’s Univ Bull Fac Hum Relat 13:117–128 (in Japanese)

Shimitutani S, Inakura N (2007) Japan’s public long-term care insurance and the financial condition of insurers: evidence from municipality-level data. Gov Audit Rev 14:27–40

Nakamura H (2006) Effect of received condition of long-term care insurance on the regional difference of the certification rate of the disability. J Health Welf Stat 53:1–7 (in Japanese)

Yoshimura N, Muraki S, Oka H, Mabuchi A, En-Yo Y, Yoshida M, Saika A, Yoshida H, Suzuki T, Yamamoto S, Ishibashi H, Kawaguchi H, Nakamura K, Akune T (2009) Prevalence of knee osteoarthritis, lumbar spondylosis and osteoporosis in Japanese men and women: the research on osteoarthritis/osteoporosis against disability study. J Bone Miner Metab 27:620–628

Orimo H, Hashimoto T, Sakata K, Yoshimura N, Suzuki T, Hosoi T (2000) Trends in the incidence of hip fracture in Japan, 1987–1997: the third nationwide survey. J Bone Miner Metab 18:126–131

Yoshimura N, Suzuki T, Hosoi T, Orimo H (2005) Epidemiology of hip fracture in Japan: incidence and risk factors. J Bone Miner Metab 23:78–80

Orimo H, Yaegashi Y, Onoda T, Fukushima Y, Hosoi T, Sakata K (2009) Hip fracture incidence in Japan: estimates of new patients in 2007 and 20-year trends. Arch Osteoporos 4:71–77

Ueshima H, Ohsaka T, Asakura S (1986) Regional differences in stroke mortality and alcohol consumption in Japan. Stroke 17:19–24

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Grant-in-Aid for H17-Men-eki-009 (Director, Kozo Nakamura), H20-Choujyu-009 (Director, Noriko Yoshimura), H23-Choujyu-002 (Director, Toru Akune), and H-25-Chojyu-007 (Director, Noriko Yoshimura) of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Further grants were provided by Scientific Research B24659317, B23390172, B20390182, and Challenging Exploratory Research 24659317 to Noriko Yoshimura; B23390357 and C20591737 to Toru Akune; B23390356, C20591774, and Challenging Exploratory Research 23659580 to Shigeyuki Muraki; Challenging Exploratory Research 24659666, 21659349, and Young Scientists A18689031 to Hiroyuki Oka, and collaborative research with NSF 08033011-00262 (Director, Noriko Yoshimura) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in Japan. The sponsors did not contribute to the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or the writing of the manuscript.

The authors wish to thank Ms. Kyoko Yoshimura, Mrs. Toki Sakurai, and Mrs. Saeko Sahara for their assistance with data consolidation and administration.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Yoshimura, N., Akune, T., Fujiwara, S. et al. Incidence of disability and its associated factors in Japanese men and women: the Longitudinal Cohorts of Motor System Organ (LOCOMO) study. J Bone Miner Metab 33, 186–191 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00774-014-0573-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00774-014-0573-y