Abstract

Vaginal birth may result in damage to the levator ani muscle (LAM) with subsequent pelvic floor dysfunction and there may be accompanying psychological problems. This study examines associations between these somatic injuries and psychological symptoms. A qualitative study using semi-structured interviews to examine the experiences of primiparous women (n = 40) with known LAM trauma was undertaken. Participants were identified from a population of 504 women retrospectively assessed by a perinatal imaging study at two obstetric units in Sydney, Australia. LAM avulsion was diagnosed by 3D/4D translabial ultrasound 3–6 months postpartum. The template consisted of open-ended questions. Main outcome measures were quality of information provided antenatally; intrapartum events; postpartum symptoms; and coping mechanisms. Thematic analysis of maternal experiences was employed to evaluate prevalence of themes. Ten statement categories were identified: (1) limited antenatal education (29/40); (2) no information provided on potential morbidities (36/40); (3) conflicting advice (35/40); (4) traumatized partners (21/40); (5) long-term sexual dysfunction/relationship issues (27/40); (6) no postnatal assessment of injuries (36/40); (7) multiple symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction (35/40); (8) “putting up” with injuries (36/40); (9) symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (27/40); (10) dismissive staff responses (26/40). Women who sustain LAM damage after vaginal birth have reduced quality of life due to psychological and somatic morbidities. PTSD symptoms are common. Clinicians may be unaware of the severity of this damage. Women report they feel traumatized and abandoned because such morbidities were not discussed prior to birth or postpartum.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Maternal birth complications in the form of levator ani muscle (LAM) damage are more common than generally assumed (Dietz 2013).

Anecdotal evidence suggests these injuries may be a marker for psychological trauma (Skinner and Dietz 2015). This study of maternal birth experiences examines the association between traumatic vaginal delivery and psychological symptoms. Unexpected and unexplained birth events may be particularly distressing; childbirth is commonly viewed as a predictable and positive life experience (Ayers and Ford 2009). Surprisingly, maternal reports of pelvic organ prolapse, sexual dysfunction, and fecal and/or urinary incontinence are rarely investigated formally as compromising psychological health after birth; often they are regarded as negligible and likely to improve over time.

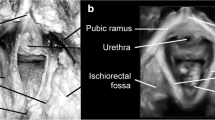

Contemporary literature usually defines somatic damage as “perineal trauma” in the sense of episiotomy and perineal tears. While there is ample literature on women’s experience of perineal birth trauma (Priddis et al. 2013; Williams et al. 2005), the interviews reported here specifically examine the consequences of LAM avulsion, although some participants also sustained severe perineal trauma. Since the advent of translabial 3D/4D ultrasound, clinicians now classify “pelvic floor trauma” differently. Major damage of this type encompasses of the levator ani muscle “avulsion” (Dietz 2004) or detachment of the puborectalis component of this LAM from the pelvic sidewall. Perineal injuries are significant but noted as separate traumas with different origins. Clinicians rarely identify LAM injury in labor wards or during the puerperium since it is commonly occult: overlying vaginal muscularis is more elastic, stretching without tearing even after the underlying muscle has exceeded its elastic limit (Dietz et al. 2007).

There is now substantial evidence from large epidemiological studies (Gyhagen et al. 2013; Glazener et al. 2013) demonstrating that vaginal childbirth, especially forceps delivery, may be associated with pelvic organ prolapse (POP), anal and urinary incontinence, and sexual dysfunction. A difficult delivery with resulting somatic LAM trauma may have psychological consequences. Postpartum trauma symptoms can hinder mother and baby bonding and maternal adjustment, negatively affect children’s behavior and development (Garthus-Niegel et al. 2017), adversely affect relationships, and diminish the quality of sexual and marital interactions (Iles et al. 2011; Fenech and Thomson 2014; Coates et al. 2014). Recognition of birth-related post-traumatic stress due to life-threatening complications with long-term mental health issues has occurred only recently (Furuta et al. 2014; McKenzie-McHarg et al. 2015); the literature does not include pelvic floor dysfunction as a risk factor. Hence, we attempted, in a qualitative study, to explore and describe women’s experiences of major LAM pelvic floor trauma.

Methods

Mothers with documented full unilateral or bilateral LAM avulsions were approached for interviews. Informed consent was obtained and semi-structured interviews undertaken with a focus on individual experiences. The template comprised open-ended questions on antenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum care (see Appendix 1). The interviewer was a midwife with extensive professional experience. Data used in this analysis was obtained retrospectively from participants of the Epi-No trial (Kamisan Atan et al. 2016) and corresponding birth records at two major hospitals in Sydney from May 2013 to October 2014. Primiparous women with major LAM avulsion were identified from a population of 504 women who had returned for a postnatal appointment in the context of this trial. Pelvic floor injuries were diagnosed by 3D/4D translabial ultrasound 3–6 months after the birth of a first child at term, following an uncomplicated singleton pregnancy. Multislice imaging was employed according to a previously published methodology (Dietz 2007; Dietz et al. 2011).

Main outcome measures

The main outcome measures comprised efficacy of hospital antenatal education regarding comprehension of birth process; existence of informed consent to explain potential intrapartum interventions; memory of intrapartum intervention, e.g., syntocinon induction, length of second stage, mode of delivery, forceps/vacuum, epidural, episiotomy, and perineal tears; and birth weight of baby. Other aspects were clinicians’ attitudes and advice during birth; incidence and/or efficacy of postnatal assessment of injuries and follow-up; referrals to address symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction; occurrence of sexual health education after delivery; reactions and coping behavior of mother and partner regarding pelvic floor dysfunction and bladder and bowel changes (if any); clinician response to maternal symptoms; maternal emotional state during and after delivery; short/long-term coping mechanisms; and long-term medical follow-up.

Interviews

Women were invited to participate in this study by telephone/email. Options to engage in an interview for 35–40 min were proposed as being via telephone, in a clinical environment face-to-face, or by Skype software application. All participants received a written invitation with information about questions and consent forms. No participants agreed to interviews being audiotaped so the interviewer took written notes which were then emailed to the participants for formal authorization as an unbiased record. Women were given the opportunity to add or change information on these scripts.

Ethical considerations

This study received ethical approval from the local Human Research Ethics Committees (NBMLHD 07-021 and SLHD RPAH zone X05-0241). Consideration was given to the personal nature of questions and responses; anonymity, confidentiality, valid consent, and the right to withdraw from the study were emphasized. All participants were offered clinical and psychological consultation if required.

Analysis

Thematic analysis of purposeful sampling (Braun and Clarke 2006; Gale et al. 2013) was undertaken by two researchers with an inductive approach. A framework method analysed data and consistent coding matched identified themes in the template.

Saturation of answers was noted at 14 when no new themes were introduced. In-depth analyses of key themes took place across the data set and were observed to be 10. These were renamed “statement categories” and reduced to four main overarching themes. Experiences of each participant remained connected to their account within the matrix so the context was not lost. Themes were observed to complement and clarify retrospective quantitative findings on the EpiNo database. Examples where thematic data converged with quantitative findings were women with sexual dysfunction and multiple somatic pelvic floor symptoms displayed psychological trauma and reported marital disharmony (themes 2 and 3) after sustaining forceps deliveries, long second stages, and/or macrosomic babies (see Tables 1 and 2).

Results

The following statement categories and clinical attributes were identified within the context of the interview and quantitative findings (see Table 2, Table 3, and Table 4).

After analysis, we identified four overarching themes:

Theme 1: Lack of accurate information about potential birth complications resulting in pelvic floor morbidities (statement categories: 1–3, 6)

A core finding was women reported they would have preferred accurate information on potential complications of vaginal birth, along with options about given clinical situations. Predominant issues that obscured understanding of somatic trauma and its effects were reported to be inadequate preparation in scheduled classes. Mothers had not understood what was happening to them and felt educators idealized birth. “…I felt brainwashed -classes are biased towards natural birth and seem to romanticize delivery.” Many noted they knew motherhood would be difficult but became overwhelmed when physical and emotional health or relationships were compromised to such an extent. Some participants felt the need to warn other pregnant women. “...I had to bite my hand to stop myself telling other women how bad birth and delivery will be.” Conflicting advice exacerbated the impact of traumatic intrapartum events. “…The doctor wanted to take me to theatre ...but the midwife wanted to wait.” Women stated they were traumatized by unexpected and unexplained procedures and distress extended into the postnatal period. “…No one checks you after birth in the hospital or later – it stays hidden. I feel isolated and abandoned.” Most complained that clinicians dismissed injuries that were obvious to women and did not offer assessment. “… No one informed me about damage down there. I had never heard of pelvic organ prolapse or rectocele until I had them? … Now I have to live with debilitating injuries and life afterwards.” Most mothers undertook pelvic floor muscle exercises but resigned themselves to damage when there was no positive effect. Lack of therapeutic efficacy seemed to exacerbate psychological issues. Interview findings noted altered body image. “…I hate my body it has never returned to normal.” Women wondered why they had not been informed of risks and warned. “…Overall, it has been a nightmare of no medical accountability, no support, lack of continuity…. My life has been severely affected by a terrible labour and delivery that left me with a blown out pelvic floor.”

Theme 2: Impact on partner and sexual relationships (statement categories: 4, 5)

Interviewees’ reported communication between partners regarding “sex” was strained and both parties felt “…let down” by both antenatal and postnatal clinicians who had told them sex would return to normal after birth. When this did not eventuate, women became anxious and blamed themselves; many stated these inaccurate facts had adversely affected their sexual lives and marital harmony. Most participants said they were unsure whether partners really understood their sexual dysfunction post birth. Resumption of sexual activity was delayed for up to a year postpartum, and it was experienced as emotional and invasive, sometimes initiating flashbacks of delivery. Some women stated they wanted vaginal plastic surgery or asked the interviewer to talk to their partners. Many believed men thought their complaints or silence was an excuse to avoid sex; most participants said they had no sensation and just wanted sex over; one woman said she felt like a “…sausage is between my legs and sex is impossible”; varying degrees of pain, dryness, and scarring were all noted up to a year or more later “…Every aspect of my life has been affected including my relationship with the baby’s father who has left me. How can I ever navigate sex with another partner?”

Theme 3: Somatic and psychological symptoms (statement categories: 6–9)

Open-ended questions regarding bladder, bowel, and sexual function yielded a number of explicit responses: many reported symptoms of prolapse such as a vaginal bulge or dragging sensation; vaginas were perceived as altered and “not belonging” to the woman, “…my whole vulva was hanging out – I could see it in the mirror from behind and it did not seem part of me – everything is unrecognizable down there.”

Urinary incontinence varied from a total lack of control in the first months postpartum to stress incontinence when exercising “…after I change my baby’s nappy I need to change mine.” Multiple symptoms of bowel dysfunction were reported, but anal incontinence was rarely mentioned in interviews, although evident in quantitative data of assessments by doctors. In about 2/3 of women, somatic symptoms were paired with psychological symptoms suggestive of PTSD, such as flashbacks, dissociation, avoidance reactions, and anxiety. Women reported that they were “…shell shocked,” “…in a bad / terrible place,” “…did not tell anyone,” “…detached,” denying symptoms; needing to flee from the hospital to the security of home; “…numb;” experiencing poor bonding with baby. Many were still numb at the time of their ultrasound appointment (performed as part of the parent study) 3–6 months after birth and did not retain information or understand injuries “…I was in shock...why am I unable to get any health professional to understand? I feel abandoned.” “… I am weak and do not measure up as a mother.” “…This is a hidden injury; I can not tell anyone.”

Theme 4: Dismissive reactions from postnatal clinicians (statement categories: 5–10)

Women reported health care providers dismissed their attempts to enquire about postpartum birth damage symptoms and they became anxious, numb, and isolated, especially when clinicians did not offer assessment or treatment options. At interview, they exhibited shame and stigma about vaginal injuries that had been clinically viewed as normal outcomes of birth and often said “…I just put up with the consequences- it is part of having a baby.” Another said: “I was in shock – devastated and unable to get any health professional to understand. I was overwhelmed by their incompetence and unconcerned manner.” Interviewees reported clinicians rarely allowed them to discuss personal/sexual problems and dismissed their concerns with comments like “…it will get better.” Women had hoped for more information and noted: “…GP’s are not of any use when you mention intimate stuff- they are too busy.”

Discussion

Main findings

This study increases our knowledge regarding postpartum psychological experiences of women known to have suffered major somatic pelvic floor damage. It offers insight into mothers’ coping behavior concerning lack of antenatal information on risk factors of vaginal births; postpartum impact on marital relationships; discovery of unexpected somatic vaginal symptoms; and feeling dismissed by clinicians. During interviews, women were given an opportunity to reflect on antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum issues that had previously been unidentified. Many exhibited adverse coping behaviors that included the following: anxiety, avoidance, detachment from babies/ partners, and numbing; distress that sexual relations were almost impossible and involved unwelcome flashbacks of the birth; feelings of stigma that their bodies had not met the required standards of a natural birth; a belief had failed as mothers and could not tell anyone. Women stated that contact with researchers in this study had been a welcome chance to debrief because no one else believed them. Most said they had never heard of rectoceles, cystoceles, or vaginal prolapses and wondered why clinicians had not informed them prior to delivery.

A significant finding is that participants displayed psychological trauma symptoms as maladaptive “coping behaviors” to unexpected and unexplained somatic injuries and were unable to move forward.

Ayers’ team in the UK (Ayers et al. 2015) have extensive research regarding the causes and effects of PTSD after birth and propose that substantial empirical studies now demonstrate a proportion of women develop postpartum PTSD due to events of birth. Related symptoms of anxiety, numbness, avoidance, dissociation, and flashbacks of traumatic deliveries, as specified in the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-V (U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs 2017), are observed to have potentially wide-ranging consequences. Minimal research exists on prevention, assessment, and intervention of this often-undisclosed perinatal mental illness, and many women do not typically receive the treatment they need to recover because they feel stigmatized and conceal distress. These UK studies purport contributing factors of stigma may be both external and internal, the former involving stigmatizing attitudes of the general public and the latter where mothers believe this negative appraisal applies to them (Moore et al. 2016).

Participants in our study exhibited comparable symptoms, along with negative perceptions of shame and failure from unforeseen somatic vaginal injuries. Women reported they did not really understand their physical damage and mental health consequences due to insufficient antenatal discussion of birth risk factors. This correlates with research that notes a plausible reason women do not seek help is their lack of information (Jorm et al. 2006). Studies linking PTSD-related symptoms as psychological sequelae of somatic pelvic floor damage are absent in the worldwide literature and not included in Ayers’ research; this cohort appears to be unidentified and unrecognized.

Refusal of audiotaped interviews by women in this study also seemed to reveal substantial symptoms of anxiety and stigma regarding disclosure of birth damage because they did not want to upset maternity clinicians. One author proposed that affected mothers’ inherent distress is a direct result of trauma sustained in the labor ward and yet women feel bound to be grateful to the very people who caused that damage (Hilpern 2003).

Usually, qualitative research relies on mothers’ own reflections of morbidities (Herron-Marx et al. 2007) and does not employ accurate assessment as observed in this study. There is evidence in the literature of analogous poor data regarding postnatal care that notes lack of insight into what comprises normal postnatal pelvic floor recovery and severe morbidities; women are typically uniformed about pelvic floor dysfunction and discuss options with friends who falsely tell them injuries will resolve (Buurman and Lagro-Janssen 2013). One review observes there is a profound silence in the research that surrounds this pivotal postpartum period (Borders 2006).

Most agree that an imperative exists to explore ways of enabling women to discuss physical, psychological, sexual, and social demands related to childbearing and decide whose responsibility this is, when leading strategic development of postnatal services. Our participants reported they were “in the dark” and encountered significant challenges finding physical assessment so they remained silent. Undisclosed perinatal mental health issues are known to result in adverse outcomes for women and their families. This research observed a direct association between somatic injury and psychological trauma after birth that was frequently undisclosed.

Strengths and limitations

This interview study built on quantitative data that had retrospectively been diagnosed in women with LAM avulsion (Dietz 2013) to clarify qualitative findings. An objective diagnosis of major somatic trauma was implemented, thus avoiding the detection bias inherent in intrapartum clinical diagnosis. Contrary to the original study plan, we were unable to audiotape interviews. Women were fearful their negative perceptions of maternity care might be quoted back to clinicians despite the caveat of privacy and confidentiality. Disclosure of these traumas was difficult and appeared to reflect stigmatized belief processes that women’s bodies had failed them.

One interview was conducted by email because a distressed woman requested this alternative mode during a 30-min discussion inviting her to be part of the study. She explained that even after 2 years, she was still experiencing trauma symptoms and wanted to be included; it seemed urogynecologists from this research had assisted her debriefing at her 3-month postnatal ultrasound appointment, but she noted: “…I have unfinished business about this labour.” It was decided this data should be allowed because the authors believed her input was credible and added to the data set by highlighting the intense psychological trauma she experienced after events of birth and discovering injuries. Her replies were articulate and demonstrated an authentic voice.

Comments: “…There is a big push towards natural delivery... they all say that you were made for it and this is how it’s going to be… even if the baby is sideways and won’t turn, we will try everything to get him out naturally…because that’s what everyone wants... I still think about my delivery all the time- it is always on my mind. I experience anxiety, panic attacks and flashback…I would like that delivery to be erased from my brain if possible.”

We were mindful that these interviews had the potential of distressing participants, so endeavored to assist women with amenable options to protect their mental health. Recent research has shown writing about traumatic events can decrease postpartum symptoms of anxiety or PTSD (Thompson et al. 2015). Although transcribing responses during interviews was not the intention, the process elicited optimal data because women could add/change information later on the template. Generally, the choices of phone, face to face, or Skype gave flexibility and facilitated rapport and respect that enabled women to speak freely. Mothers gave birth in public hospitals and represented the majority from a publicly funded Australian health care system that entitles all residents to subsidized treatment from accredited clinicians. A few had private obstetricians but all practitioners are regulated by a national agency. Recruitment of participants was problematic because women hesitated to trust the study or interviewer and skill was required to reassure them. All aspects of the interview required reassurance as regards privacy and confidentiality. Sensitive questions on sexual dysfunction entailed diplomacy; many women were not prepared to go into detail; participants addressed these issues later in writing or not at all. Findings of anxiety and “avoidance of disturbing memories” emerged during interviews. Taped interviews may have yielded poorer information on sensitive topics. Participants collaborated regarding consent forms and self-editing of the template, but at times took weeks to return their version as a record. Women were often emotional during interviews, necessitating empathy, as well as extensive knowledge of maternity and mental health issues. All participants were offered clinical and psychological follow-up and often remained in contact with the interviewer. Fifteen women were given details of available urogynecologists and/or psychologists. In NSW, midwives do not have the scope of practice to assess major pelvic floor trauma such as levator avulsion and 3rd/ 4th degree tears; urogynecologists’ expertise is essential for this degree of somatic trauma; all clinicians are mandated to adhere to Maternity-Towards Normal Birth (Anonymous 2010), and this policy does not include risk factors of pelvic floor complications; perineal injuries are frequently confused with the more recently classified LAM damage; maternity units do not formally assess antenatal fetal weight regarding macrosomia to forewarn women of risks to pelvic floor function. The interviewer corresponded with relevant clinicians regarding participant compliance. This was deemed judicious despite time restraints, given the risk of serious psychological morbidity after severe somatic damage. During each interview, vigilance concerning mental distress was essential and the option of abandoning the interview was canvassed repeatedly. None of the 40 women exited the study during data acquisition. The interviewer received debriefing sessions with a hospital counselor.

Interpretation

Major somatic trauma after vaginal birth in the form of levator avulsion is one of the main causes of pelvic floor dysfunction with potential for lifelong morbidity. Correspondingly, undisclosed perinatal mental health issues are a major public health concern. Women in this study sustained LAM avulsion with resultant morbidities and exhibited significant psychological morbidities in the form of anxiety, PTSD symptoms, and stigma. Participants were often relieved to be interviewed and expressed comments like: “…your study is a lifeline, no one else seems to believe me and I do not know where to turn for help.” Themes demonstrated they experienced multiple barriers to help-seeking behavior and felt abandoned by a medical system that did not recognize or identify either trauma. How can clinicians address some of the issues raised by our interviewees? The solution, like the problems described, is complex. Providing potentially alarming details about physical and psychological complications needs to be done in such a way as to enhance the contract of care and mutual respect rather than increasing anxiety; this may require additional training for midwives, obstetricians, GPs, and other involved clinicians. This is particularly urgent in view of a recent UK Supreme Court decision, which explicitly affirms the autonomy of the obstetric patient (Montgomery v Lanarkshire Health Board 2015).

Conclusions

Women in this study suffered considerable somatic and psychological morbidities, including pelvic organ prolapse, urinary and/or fecal incontinence, sexual dysfunction, and PTSD symptoms. It seems their reports were dismissed by clinicians as foreseen issues after birth. Participants’ undisclosed postpartum mental health issues could be seen as a serious by-product of a health care system that has not recognized or identified women’s assertions of somatic birth injury. Poor knowledge and stigma noted in this study also appear to have been barriers to help-seeking behavior that adversely affected lifestyle. Psychological symptoms uncovered in our interviews suggest a possible formal diagnosis of PTSD in some women: a disorder that occurs secondary to exposure to stressors that are outside the usual range of human experience.

It seems that women who have sustained these somatic vaginal injuries and resultant emotional distress could be greatly assisted by perinatal clinicians who acknowledge their concerns and provide relevant diagnostic and therapeutic services. This may include (1) routinely discussing potential complications of vaginal delivery during antenatal consultations; how information and responsibility for decision-making will be shared; transcribing this information into a Birth Document that both patient and provider sign; (2) comprehensively identifying and enquiring about physical and psychological problems during postpartum consultations; (3) validating maternal concerns as they arise; and (4) implementing evidence-based assessment services with both partners being included as appropriate.

References

American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM–5) (2013) Posttraumatic stress disorder, 5th edn. American Psychiatric Association, Arlington

Anonymous (2010) Maternity: Towards Normal Birth in NSW, in PD 2010-045, NSW Health, Sydney, 2010. Available at URL: http://www1.health.nsw.gov.au/pds/ActivePDSDocuments/PD2010_045.pdf [Accessed 4 June 2017]

Ayers S (2013) All change...what does DSM-5 mean gor perinatal PTSD ? International network for perinatal PTSD research. Centre for Maternal and Child Health. City, University of London. [Accessed 5 Mar 2017]. Available at URL: https://blogs.city.ac.uk/birthptsd/2013/06/05/dsm-and-perinatal-ptsd/

Ayers S, Ford E (2009) Birth trauma: widening our knowledge of postnatal mental health. Eur Psychol 11(16):1–4. Available at URL: http://www.ehps.net/ehp/index.php/contents/article/viewFile/ehp.v11.i2.p16/941 [Accessed 7 Mar 2017]

Ayers S, McKenzie-McHarg K, Slade P (2015) Post-traumatic stress disorder after birth. J Reprod Infant Psychol 33(3):215–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2015.1030250

Borders N (2006) After the afterbirth: a critical review of postpartum health relative to method of delivery. J Midwifery Women’s Health 51(4):242–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmwh.2005.10.014

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3(2):77–101. Available at URL: http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/11735 [Accessed 7 Mar 2017]

Buurman MB, Lagro-Janssen AL (2013) Women’s perception of postpartum pelvic floor dysfunction and their help-seeking behaviour: a qualitative interview study. Scand J Caring Sci 27(2):406–413. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.01044.x

City University London(2016) Centre for Maternal and Child Health Research. The City Birth Trauma Scale (CityBiTS). [Accessed 22 Feb 2017] Available on URL: https://blogs.city.ac.uk/mchresearch/city-measures/

Coates R, Ayers S, de Visser R (2014) Women’s experiences of postnatal distress: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 14(359):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-14-359

Dietz HP (2004) Ultrasound imaging of the pelvic floor. Part II: Three-dimensional or volume imaging. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 23(6):615–625. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.1072

Dietz HP (2007) Quantification of major morphological abnormalities of the levator ani. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 29(3):329–334. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.3951

Dietz HP (2013) Pelvic floor trauma in childbirth. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol 53(3):220–230. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajo.12059

Dietz HP, Gillespie A, Phadke P (2007) Avulsion of the pubovisceral muscle associated with large vaginal tear after normal vaginal delivery at term. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol 47(4):341–344. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1479-828X.2007.00748.x

Dietz HP, Bernardo MJ, Kirby A, Shek KL (2011) Minimal criteria for the diagnosis of avulsion of the puborectalis muscle by tomographic ultrasound. Int Urogynecol J 22(6):699–704. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-010-1329-4

Fenech G, Thomson G (2014) Tormented by ghosts of their past’: a meta synthesis to explore the psychosocial implications of a traumatic birth on maternal wellbeing. Midwifery 30(2):185–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2013.12.004

Furuta M, Sandall J, Cooper D, Bick D (2014) The relationship between severe maternal morbidity and psychological health symptoms at 6–8 weeks postpartum: a prospective cohort study in one English maternity unit. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 14(133):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-14-133.

Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S (2013) Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 13(117):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

Garthus-Niegel S, Ayers S, Martini J, Von Soest T, Eberhard-Gran M (2017) The impact of postpartum post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms on child development: a population-based, 2-year follow-up study. Psychol Med 47(1):161–170. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329171600235X

Glazener C, Elders A, MacArthur C, Lancashire RJ, Herbison P, Hagen S, Dean N, Bain C, Toozs-Hobson P, Richardson K, McDonald A, McPherson G, Wilson D, for the ProLong Study Group (2013) Childbirth and prolapse: long-term associations with the symptoms and objective measurements of pelvic organ prolapse. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 120(2):161–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.12075

Gyhagen M, Bullarbo M, Nielsen TF, Milsom I (2013) Prevalence and risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse 20 years after childbirth: a national cohort study in singleton primiparae after vaginal or caesarean delivery. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 120(2):152–160. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.12020

Herron-Marx S, Williams A, Hicks C (2007) A Q methodology study of women’s experience of enduring postnatal perineal and pelvic floor morbidity. Midwifery 23(3):322–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2006.04.005

Hilpern K. (2003) The unspeakable trauma of childbirth. SMH. Available from URL: http://www.smh.com.au/articles/2003/06/05/1054700311400.html [accessed 15 July 2016]

Iles J, Slade P, Spibey H (2011) Posttraumatic stress symptoms and postpartum depression in couples after childbirth: the role of partner support and attachment. J Affect Disord 25(4):520–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.12.006

Jorm AF, Christensen H, Griffiths KM (2006) The public’s ability to recognize mental disorders and their beliefs about treatment: changes in Australia over 8 years. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 40(1):36–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01738.x

Kamisan Atan I, Shek KL, Langer S, Guzman Rojas R, Caudwell-Hall J, Daly JO, Dietz HP (2016) Does the EPI-No prevent pelvic floor trauma? A multicentre randomised controlled trial. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 123(6):995–1003. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.13924

McKenzie-McHarg K, Ayers S, Ford E, Horsch A, Jomeen J, Sawyer A, Stramrood C, Thomson G, Slade P (2015) Post-traumatic stress disorder following childbirth: an update of current issues and recommendations for future research. J Reprod Infant Psychol 33(3):219–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2015.1031646

Montgomery v Lanarkshire Health Board (2015) Supreme Court of the United Kingdom. London. Available at URL: https://www.supremecourt.uk/decidecases/docs/UKSC_2013_0136_Judgment.pdf [Accessed 4 Mar 2017]

Moore D, Ayers S, Drey N (2016) A thematic analysis of stigma and disclosure for perinatal depression on an online forum. JMIR Ment Health 3(2):e18. https://doi.org/10.2196/mental.5611

Priddis H, Dahlen H, Schmied V (2013) Women’s experiences following severe perineal trauma: a meta ethnographic synthesis. J Adv Nurs 69(4):748–759. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12005

Skinner EM, Dietz HP (2015) Psychological and somatic sequelae of traumatic vaginal delivery: a literature review. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol 55(4):309–314. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajo.12286

Thompson S, Ayers S, Crawley R, Thornton A, Eagle A, Bradley R, Lee S, Moore D, Field A, Gyte G. Smith H. (2015). Using expressive writing as an intervention to improve postnatal wellbeing. Paper presented at the 2015 Society for Reproductive and Infant Psychology (SRIP) Conference, 14–09-2015 -15-09-2015, University of Nottingham, UK

U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs (2017) PTSD: National Centre for PTSD. Available at URL: http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/PTSD- overview/dsm5_criteria_ptsd.asp [Accessed 3 Mar 2017]

Williams A, Lavender T, Richmond DH, Tincello DG (2005) Women’s experiences after a third-degree obstetric anal sphincter tear: a qualitative study. Birth 32(2):129–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0730-7659.2005.00356.x

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Elizabeth Mary Skinner: project development, template construction, data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing

Professor Bryanne Barnett: manuscript writing

Professor Hans Peter Dietz: project development, approval of protocols, data analysis, manuscript writing

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Brief summary

Symptoms of postpartum post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) were commonly reported by women who delivered vaginally and sustained unexpected and unexplained major pelvic floor trauma.

Appendix 1: Template of open-ended questions for interviewees

Appendix 1: Template of open-ended questions for interviewees

Introduction

-

1.

Confirm that the participant has signed the consent form.

-

2.

Explain the interview can be discontinued if the participant wishes.

-

3.

Indicate that the participant can withdraw their responses later if required

-

4.

Clarify there are no right or wrong answers.

-

5.

Emphasize responses are strictly private and confidential.

-

6.

Explain that some of the questions may be sensitive and personal.

-

7.

Affirm that the researchers appreciate the assistance of participants.

Relevant participant information extracted from EpiNo database

Participant name:

BMI (Pre-& during pregnancy):

Height:

Date/ mode/ duration of interview:

Maternal age at delivery:

Email:

Mobile/Landline no:

Mode of Delivery (induction, epidural, Forceps, Ventouse, episiotomy, perineal and vaginal tears):

Ist Stage Labour duration:

2nd Stage Labour duration:

Baby weight/ head circumference/ position:

Estimated Date of Delivery:

Date of Delivery:

Gestation at delivery:

Postnatal Symptoms:

Domain 1: Pre/ Antenatal Care

-

What did you know about childbirth at this stage?

-

What did you understand about your body regarding childbirth at this stage?

-

What or who was the source of your information?

Domain 2: Antenatal Care

-

Where did you go for antenatal care and education - if anywhere?

-

What can you remember about this experience?

-

Can you tell me any information on childbirth and delivery you received during the antenatal period?

-

What impact did this education have on you and your partner at that time?

-

Now you have delivered would you change anything about your antenatal care and education?

-

What were your expectations regarding childbirth, your health and living with baby at home afterwards?

Domain 3: Labour and Delivery

-

How did you deliver your baby?

-

Can you describe the course of events?

-

Did you understand what was happening?

-

How did you feel when baby was born?

-

What was your partner’s reaction during labour and delivery?

Domain 4: Postnatal Period – in hospital

-

Tell me about your experience in the postnatal ward?

-

What physical changes to your body did you notice?

-

When you passed urine or opened your bowels was there any difference from before birth?

-

Tell me about any psychological changes at this stage after birth?

-

Did these changes affect you while you were in hospital (if relevant)?

-

Did you notice that your perineal area (around vagina and anus) felt any different?

-

What was your experience of breast-feeding and time with your baby?

-

Did you notice that your vagina felt different after the birth?

-

Who did you tell about any alterations to your perineal area (if any)?

-

What was your partner’s reaction to the postnatal stay?

Domain 5: Postnatal Period – adjustment at home

-

Can you tell me about your physical health at this stage? For example: passing urine, opening bowels, vaginal sensation?

-

How was your psychological health at this stage after the birth?

-

Did you tell anyone about any changes to your physical and/ or psychological health?

-

How was your relationship with your baby at this stage?

-

How did you feel about your body image at this stage?

-

Were your expectations prior to the birth similar to that which occurred?

-

How were you feeling about sex?

-

What was happening with your partner at this time?

-

Did you want to debrief about your delivery at this point?

Domain 6: Long term - after the birth of the baby /before restorative surgery

-

Can you tell me about your general physical health?

-

Can you tell me about your emotional or psychological health?

-

Is passing urine the same as before you were pregnant?

-

Is your vaginal area the same as before pregnancy?

-

Are you able to use tampons?

-

Have you noticed anything different about your bowel habits?

-

Can you tell me about your overall body image at this stage?

-

Do you think childbirth has affected your activities of daily living?

-

Are you able to discuss any changes to your urinary, bowel, vaginal or emotional health with anyone?

-

Have you resumed sex with your partner? If so, does it feel any different to before your pregnancy?

-

Do you know how your partner is feeling about sex with you at this stage?

-

Do you still want to debrief or talk about your delivery?

-

What are your memories of your labour ward and postnatal experiences now

Comments:

Confirmation of Accuracy of Interview Notes

This is an accurate account of my responses discussed with the researcher from Sydney Medical School, Nepean Campus, The University of Sydney. This research explores women’s experiences of physical vaginal birth trauma. I have signed and witnessed the relevant consent form and read the participant information sheet.

Name:

Date:

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Skinner, E.M., Barnett, B. & Dietz, H.P. Psychological consequences of pelvic floor trauma following vaginal birth: a qualitative study from two Australian tertiary maternity units. Arch Womens Ment Health 21, 341–351 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-017-0802-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-017-0802-1