Abstract

Perinatal depression (PND) is a common complication of pregnancy and postpartum associated with significant morbidity. We had three goals: (1) to explore the performance of a new lifetime version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS-Lifetime) to assess lifetime prevalence of PND; (2) to assess prevalence of lifetime PND in women with prior histories of major depressive episode (MDE); and (3) to evaluate risk factors for PND. Subjects were from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA). The EPDS was modified by adding lifetime PND screening questions, assessing worst episode, and symptom timing of onset. Of 682 women with lifetime MDD and a live birth, 276 (40.4 %) had a positive EPDS score of ≥12 consistent with PND. Women with PND more often sought professional help (p < 0.001) and received treatment (p = 0.001). Independent risk indicators for PND included younger age, higher education, high neuroticism, childhood trauma, and sexual abuse. We found that two in five parous women with a history of MDD had lifetime PND and that the PND episodes were more severe than MDD occurring outside of the perinatal period. The EPDS-Lifetime shows promise as a tool for assessing lifetime histories of PND in clinical and research settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Perinatal depression (PND) is a common complication of pregnancy and the postpartum period and is often defined as a major depressive episode (MDE) occurring either during pregnancy or postpartum (O'Hara and Swain 1996; Yonkers et al. 2001; Gavin et al. 2005; Gaynes et al. 2005). The time of onset in the postpartum period is a matter of some debate in the field (Elliott 2000; Wisner et al. 2010). The DSM defines postpartum depression (PPD) as the onset of symptoms occurring within the first 4 weeks postpartum (DSM-IV 1994). However, in clinical practice, a broader definition is frequently described, such as the onset of symptoms in the first 3–6 months postpartum, and thus could be considered a reasonable definition both clinically and epidemiologically (Wisner et al. 2010). The prevalence of PND ranges from 10 to 15 % and has been associated with poor childbirth outcomes such as preterm birth (Rahman et al. 2004; Smith et al. 2010). Other significant consequences include maternal suicide and infanticide (Murray and Stein 1989; Flynn et al. 2004; Marmorstein et al. 2004; Lindahl et al. 2005; Feldman et al. 2009; Field 2010), decreased maternal sensitivity and engagement (Network 1999; Campbell et al. 2004), and decreased attachment with the infant (Network 1999; Campbell et al. 2004; Paulson et al. 2006) (Fleming and Corter 1988; Murray and Cooper 1997; O'Connor and Zeanah 2003; Bergman et al. 2010).

Given the prevalence and adverse consequences of PND, lifetime PND assessment should be an essential component of the medical history of all reproductive aged women. A lifetime history of PND significantly increases the risk for a subsequent episode (O'Hara and Swain 1996; Robertson et al. 2004; Milgrom et al. 2008; Micali et al. 2011; Viguera et al. 2011). The risk of recurrence of PPD after a previous episode is 25 % (Wisner et al. 2002) and women with a history of PND must be carefully followed up as they have increased risk for both unipolar and bipolar depression (Kumar and Robson 1984; Munk-Olsen et al. 2011). Unfortunately, assessment of lifetime PND is generally not obtained in primary care, obstetrical, or mental health settings, although assessment of current PND is increasingly common. Other than asking a few general screening questions that do not allow for accurate classification, PND is not specifically assessed by most structured psychiatric diagnostic instruments including the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (First et al. 1995), the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (Wittchen 1994; Wittchen et al. 1989, 1991), and the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies (Nurnberger et al. 1994).

Our goal was to develop a lifetime assessment instrument for PND that could be used in both clinical and research settings. Cox et al. previously reported that women demonstrate accurate recall of prior episodes of PPD including both severity and duration of symptoms (Cox et al. 1984). Therefore, we focused on modifying the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) to assess lifetime episodes of PND (Cox et al. 1987). The EPDS is a common and widely studied PND screening instrument (Cox et al. 1987, 1993; Boyd et al. 2005; Hewitt and Gilbody 2009). The 10-item, self-reported EPDS focuses on current symptoms, has been successfully used during both pregnancy and postpartum (Cox et al. 1987; Gaynes et al. 2005; Flynn et al. 2011), and minimizes confounding of somatic symptoms of major depressive disorder (MDD) with the demands inherent to parenting an infant (e.g., insomnia) (Cox et al. 1987).

In addition to assessing lifetime history of PND, we wanted to assess its risk factors. The literature documents a wide range of risk factors for PND (Warner et al. 1996; O'Hara 2009; O'Hara and Swain 1996; Robertson et al. 2004; Milgrom et al. 2008), including those with overlap with non-perinatal MDD (i.e., MDD outside of the perinatal period), such as maternal age (Rubertsson et al. 2003), education (Tammentie et al. 2002), family history, prior history of MDD (Beck 2001; Milgrom et al. 2008; Kupfer et al. 2011; O'Hara and Swain 1996), social support (Brugha et al. 1998; Milgrom et al. 2008), anxiety disorders (Beesdo et al. 2007; Moffitt et al. 2007; Penninx et al. 2011a; b), and histories of abuse/trauma (Meltzer-Brody et al. 2011; Kendall-Tackett 2007; Records and Rice 2009; Silverman and Loudon 2010). However, one of the major gaps in prior studies is the lack of a comparison group of women with a diagnosis of lifetime non-perinatal MDD. Previous studies usually recruited perinatal women from the general population and then inquired about a prior history of MDD (O'Hara and Swain 1996; Milgrom et al. 2008). Some prior studies of perinatal risk factors lack any assessment of past psychiatric history (Warner et al. 1996; Tammentie et al. 2002; Rubertsson et al. 2003). In order to address these gaps, we wanted to measure the prevalence and risk factors of PND in a cohort of women with documented histories of lifetime MDD.

The three goals of our study were (1) to explore the performance of a new lifetime version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS-Lifetime) to assess lifetime prevalence of PND; (2) to assess prevalence of lifetime PND in women with histories of MDD; and (3) to evaluate risk factors for PND, including age, education, family history, personality, and histories of abuse/trauma and anxiety disorders, and compare to non-perinatal MDD and healthy controls.

Materials and methods

Study sample

NESDA is an ongoing, multi-site naturalistic cohort study examining the long-term course and consequences of MDD and anxiety disorders in adults. A detailed description of the NESDA study design and sampling procedures can be found elsewhere (Penninx et al. 2011a, b; Penninx et al. 2008). Briefly, 2,981 subjects were included for the baseline assessment in 2004–2007, consisting of healthy controls (22 %) and subjects with depressive/anxiety disorders (78 %) (Penninx et al. 2008). To represent various settings and stages of psychopathology, subjects were recruited from the community (19 %), primary care (54 %), and outpatient mental health care services (27 %). Community-based participants had previously been identified in a population-based study; primary care participants were identified through a three-stage screening procedure (involving the Kessler-10 (Kessler et al. 2002) and the short-form Composite International Diagnostic Interview psychiatric interview by phone) (Gigantesco and Morosini 2008) conducted among a random sample primary care; and mental healthcare participants were recruited consecutively when newly enrolled at 1 of the 17 participating mental health organization locations (Bijl et al. 1998; Landman-Peeters et al. 2005; Donker et al. 2010). Controls were recruited from two groups: (1) from primary care settings where subjects had agreed to undergo a mental health screen and were completely negative for a psychiatric disorder and (2) a prior cohort study conducted in The Netherlands that recruited adolescents at risk for anxiety and depression based on family history (Landman-Peeters et al. 2005). All subjects were administered with the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (version 2.1) (Wittchen et al. 1991) to establish DSM-IV diagnoses of psychiatric disorders (DSM-IV 1994), including MDD. The Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) is highly reliable and valid in assessing psychiatric disorders (Wittchen et al. 1991) and was administered by specially trained research staff. Subjects with insufficient command of the Dutch language or a primary clinical diagnosis of bipolar disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, severe substance use disorder, psychotic disorder, or organic psychiatric disorder were excluded.

For the present study, we used data from the baseline, 2-year and 4-year follow-up assessments with the EPDS-Lifetime included in the 4-year assessment. The research protocol was approved by the ethics committees of participating universities, and all participants provided written informed consent.

PND assessment

We are unaware of a gold standard assessment tool for lifetime assessment of PND (Gaynes et al. 2005). We therefore developed a new lifetime PND questionnaire derived from the EPDS (Table 1) (Cox et al. 1987). The EPDS was designed to identify current PND symptoms and has good sensitivity and specificity (Gavin et al. 2005). We modified the EPDS to assess lifetime PND retrospectively (EPDS-Lifetime). A positive score on the original 10-item EPDS was defined as a total score ≥12 and based on standard literature cutoff scores (Cox et al. 1987; Wisner et al. 2002). We expanded the EPDS-Lifetime by adding two screening questions prior to the 10-item EPDS: (1) “During how many of your pregnancies did you feel sad, miserable, or very anxious? By this we mean a period of at least 2 weeks when you were not yourself and which was worse than the normal ups and downs of life?” (2) “After how many of your deliveries, within the first six months postpartum, did you feel sad, miserable, or very anxious? By this we mean a period of at least 2 weeks, when you were not yourself and which was worse than the normal ups and downs of life?” For women answering yes to either question, we then asked them to focus on the worst PND episode and to complete the 10-item EPDS based on the worst episode. We believed that asking about the worst episode would increase the accuracy of reporting. We also included questions about the timing of initial onset of symptoms (trimester of pregnancy or months postpartum) and history of seeking mental health treatment for perinatal mood symptoms.

Risk factors and correlates

We examined the relation between PND and sociodemographic and other risk factors including age marital status and history of a live birth at the 4-year follow-up assessment, worst episode of lifetime PND, level of education, family history of MDD, personality (degree of neuroticism), history of childhood and adult abuse/trauma, and presence of lifetime anxiety disorder. We picked these risk factors based on the literature. Family history of MDD among first-degree relatives was obtained using the family tree method at the baseline assessment (Fyer and Weissman 1999). Personality was evaluated using the NEO personality questionnaire at the baseline assessment (Costa and McCrae 1995). The childhood trauma inventory, as assessed at baseline, quantified a cumulative childhood trauma index consisting of emotional neglect, psychological abuse, physical abuse, and sexual abuse during the first 16 years of life (Wiersma et al. 2009). Abuse that occurred after age 16 was assessed using an adverse life events scale (Brugha et al. 1985). Lifetime anxiety disorder was based on CIDI interviews at baseline, 2-year, and 4-year follow-up (Penninx et al. 2008; Boschloo et al. 2011).

Statistical analyses

Analyses were conducted using SPSS (v.15. Chicago, IL). In our sample of women with lifetime MDD who had a history of one or more live births, we explored the performance of the lifetime EPDS using descriptive statistics and tested the internal consistency using Cronbach's alpha. As an indication for the validity of the EPDS, we tested whether the clinical characteristics of non-PND (i.e., EPDS <12) and PND (i.e., EPDS ≥12) differed in a sample of women with lifetime MDD who answered yes on our two-item screener. Characteristics were summarized for women with PND and non-PND MDD and these were compared to controls using χ 2 statistics for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables. To determine whether characteristics were specific risk indicators for PND or non-PND MDD, we tested differences in characteristics between women with PND and non-PND MDD. Finally, we performed multivariate logistic regression analyses to identify potential independent risk factors for PND.

Results

Performance of the EPDS-Lifetime

We explored the performance of the EPDS-Lifetime in women with lifetime MDD who had a live birth. Of all women with valid data on the screener (N = 682), 363 women (53.3 %) screened positive on at least one of the two screening questions about lifetime mood and anxiety symptoms during pregnancy (N = 214) and/or after giving birth (N = 266) (see also Fig. 1). We assessed EPDS scores among all women who screened positive on at least one of the two screening questions and had valid data on the EPDS (n = 361). EPDS scores showed a normal distribution with a mean of 16.4 and standard deviation of 6.2. Cronbach's alpha for this scale was 0.82, indicating good internal consistency (Bland and Altman 1997).

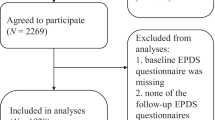

Flowchart illustrating NESDA. Of the 2,981 subjects enrolled into NESDA at baseline, 2,402 subjects had complete data at the 4-year follow-up assessment. Subject inclusion criteria were as follows: presence of a lifetime MDD (excluded: N = 743), women (excluded: N = 511), and a history of one or more live births (excluded: N = 466), leaving a sample of 682 female subjects for analyses. We included only those women who had delivered a living child to avoid confounding related to pregnancy loss and grief reactions. We also included a control group of women (N = 141) who gave birth to a living child but did not have lifetime MDD or anxiety (based on the CIDI) and did not have a diagnosis of PND (based on the modified EPDS)

Prevalence and severity of PND and MDD in the NESDA cohort

Of 361 women with MDD who endorsed one of the EPDS-Lifetime screening questions, 276 women (76.5 %) had an EPDS score ≥12 indicating PND based on our study definition. Table 2 shows that women with PND consistently demonstrated a more severe and chronic clinical course of illness than women with MDD outside of the perinatal period, including more functional impairment (p < 0.001), having sought professional help (p < 0.001), and receiving treatment (p = 0.001).

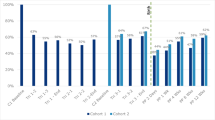

When we examined women in NESDA with histories of MDD who gave birth to a living child (N = 682), 276 (40.6 %) met criteria for PND in our study. Of those women with PND, 54.0 % had experienced an episode of MDD before the onset of PND. Figure 2 depicts the timing of the onset of symptoms in women with PND: 57.3 % reported postpartum onset and 42.7 % had onset during pregnancy. In the postpartum period, the largest percentage of women reported onset of depression occurring within the first 4 weeks postpartum—approximately 34 %. An additional 13 % reported on onset of symptoms between 4 and 12 weeks postpartum and 10 % reported onset after greater than 12 weeks (between 3 and 6 months postpartum).

Risk factors for PND and MDD

We compared risk characteristics for three groups: (1) women with a history of a live birth and histories of MDD outside of the perinatal period (non-PND MDD); (2) women with a history of a live birth and both MDD and PND (PND+MDD); and (3) a control group of women with a history of a live birth who did not report a lifetime history of PND or MDD (Table 3). The mean age at time of the NESDA 4-year follow-up interview of those with PND+MDD was 47.9 years, significantly younger than the control and non-PND MDD groups (p = 0.002). In all groups, most were married or partnered and had a high school education. A family history of MDD was significantly higher in the PND group compared to those with non-PND MDD (p = 0.03) and controls (p < 0.001). History of a lifetime anxiety disorder was significantly higher in the PND group (p = .003) and the PND group had higher neuroticism compared to the non-PND MDD group (p < 0.001) and controls (p < .001).

Rates of abuse/trauma were high but particularly in women with PND. We observed statistically significant increased rates of childhood trauma in the PND group compared to both the control (p < 0.001) and the non-PND MDD groups (p = 0.002). More than half (54.7 %) of women in the PND group reported childhood emotional neglect and this was higher compared to the MDD only group (p = .003) and controls (p < 0.001). Childhood psychological abuse was increased in those with PND versus non-PND MDD only (p = 0.02) and controls (p < 0.001). Moreover, 30.4 % of those in the PND group reported a history of childhood sexual abuse and 30.8 % reported a history of sexual abuse after age of 16. This finding was statistically significant compared to the non-PND MDD group only for those with histories of sexual abuse after age 16 (p = 0.001) but was highly significant compared to controls at both time points (p < 0.001).

Finally, multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to identify independent risk identifiers for PND compared to the non-PND MDD group. After adjustment for all sociodemographic and vulnerability factors, younger age (p = 0.009), greater education (p = 0.001), higher neuroticism (p = 0.04), childhood trauma (total score) (p = 0.03), and sexual abuse after age 16 (p = 0.04) emerged as significant independent risk factors for PND.

Discussion

The NESDA cohort is the first study to use a newly modified version of the EPDS to assess lifetime PND in a large, naturalistic cohort study. NESDA subjects were recruited from three settings representing a broad range of individuals including those with histories of MDD. Of women with histories of MDD who gave birth to a living child, 276 (40.6 %) met criteria for PND based on a positive lifetime EPDS score (EPDS ≥12).

The EPDS-Lifetime performed well in our study. The internal consistency of the EPDS was good (Cronbach's α = 0.82, with α > 0.7 defining acceptable internal consistency) (Bland and Altman 1997). These results are encouraging and suggest that the EPDS-Lifetime could be used in a variety of settings to screen women of reproductive age retrospectively for lifetime PND. It would provide valuable information regarding women at risk of developing a new episode of PND in a subsequent pregnancy and those who may be vulnerable to reproductive mood disorders across the life cycle (Schmidt et al. 1998; Bloch et al. 2000; Rubinow 2005; Rubinow and Schmidt 2006).

A strength of the present study is that it is one of the first to examine the prevalence of PND in a large cohort of women with past histories of MDD diagnosed by structured clinical interviews and to examine risk factors for PND. We found that 40 % of parous women with MDD had a history of PND. Women with PND reported the perinatal depressive episodes as more severe than MDD episodes occurring outside of the perinatal period as evidenced by being associated with greater impairments in daily functioning, more often seeking professional help and initiating treatment. In terms of risk factors for PND, we found that a family history of MDD, higher neuroticism, anxiety disorders, and trauma significantly increased risk. After controlling for all sociodemographic and vulnerability factors, multivariate logistic regression identified significant independent risk factors for PND including younger age, greater education, higher neuroticism, and history of childhood trauma and sexual abuse after age 16. Taken together and consistent with the literature (Silverman and Loudon 2010), this information supports the importance of screening and monitoring women with histories of MDD throughout the perinatal period.

In our sample, 54 % of women had already experienced an episode of MDD before the onset of PND. This finding has significance for a number of important reasons. First, the timing of onset of perinatal depression is an area of intense research and controversy within the field of perinatal psychiatry (Elliott 2000; Gaynes et al. 2005; Munk-Olsen et al. 2006; Wisner et al. 2010). The inherent heterogeneity of PND (phenotype by timing of onset of symptoms occurring before pregnancy, during pregnancy, or postpartum) has complicated efforts to determine underlying pathophysiology and to develop targeted treatments. We examined the timing of onset of PND symptoms and found that 57.3 % of subjects reported an onset after delivery, whereas 42.7 % had an onset during pregnancy. Of women reporting onset of PND in the first trimester (∼25 %), we believe it possible that most had an ongoing episode of MDD predating pregnancy.

Second, our findings support the clinical recommendation that women with histories of MDD need to be monitored during the perinatal period as they are at risk for developing PND. Most women have extensive contact with the healthcare system during pregnancy and are open to screening and interventions that improve their health and that of their child (Suellentrop et al. 2006; Dott et al. 2010). Therefore, the perinatal period presents a window of opportunity to actively screen for lifetime MDD, abuse, and other important risk factors in order to prevent adverse outcomes associated with PND.

The high prevalence of abuse in women with a history of PND is striking but consistent with previous studies (Meltzer-Brody et al. 2011; Kendall-Tackett 2007; Onoye et al. 2009; Silverman and Loudon 2010). However, the sample size of the present study is much larger than most prior work. More than half of the PND group reported histories of neglect and almost one third reported a history of sexual abuse. Furthermore, the long-term psychological consequences of sexual abuse are well documented and associated with adverse consequences on emotional and physical health (Leserman et al. 1996; McCauley et al. 1997; Kendler et al. 2000; Romans et al. 2002; Leserman 2005) and increased risk for adverse outcomes during the perinatal period (Buist 1998; Grimstad et al. 1998; Leeners et al. 2006, 2010; Lukasse et al. 2011).

The methodological strengths of this study include the analysis of a notably large sample of women with a history of MDD diagnosed by administration of a structured psychiatric interview and compared to a new lifetime assessment of PND. The primary limitations of our study are the retrospective nature of the assessment of lifetime PND and lack of data on some other aspects of pre-partum functioning. In addition, in the PND+MDD group, compared to the PND alone group, the increased psychiatric comorbidity and severity of illness could be due in part to the greater number of lifetime episodes of unipolar major depression. As women with bipolar disorder were excluded from the NESDA study, we were not able to examine the prevalence or severity of PND in those with bipolar disorder and compare to those with unipolar MDD.

Conclusions

PND is a severe and persistent form of MDD that is one of the most frequent complications of pregnancy and childbirth. NESDA is one of the first studies to carefully assess for lifetime history of PND in a large sample of women with MDD. In this sample, a new modified lifetime version of the EPDS (the EPDS-Lifetime) demonstrated great promise as a useful tool for the assessment of lifetime histories of PND. Two in five women with a live birth and a history of MDD also had lifetime PND, and the PND episodes were more severe than MDD occurring outside of the perinatal period.

Histories of abuse and trauma were significantly increased in women with PND, compared to women with non-perinatal MDD as well as healthy controls. Identification of the independent risk factors and phenotypic characteristics that distinguish PND from MDD has important and far-reaching clinical and research implications that could provide insight into psychological, biological, and genetic vulnerabilities to PND. Specifically, the perinatal period presents a window of opportunity to actively screen for lifetime histories of depression, abuse, and other important risk factors of psychiatric illness.

References

Beck CT (2001) Predictors of postpartum depression: an update. Nurs Res 50(5):275–285

Beesdo K, Bittner A et al (2007) Incidence of social anxiety disorder and the consistent risk for secondary depression in the first three decades of life. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64(8):903–912

Bergman K, Sarkar P et al (2010) Maternal prenatal cortisol and infant cognitive development: moderation by infant-mother attachment. Biol Psychiatry 67(11):1026–1032

Bijl RV, van Zessen G et al (1998) The Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS): objectives and design. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 33(12):581–586

Bland JM, Altman DG (1997) Cronbach's alpha. BMJ 314(7080):572

Bloch M, Schmidt PJ et al (2000) Effects of gonadal steroids in women with a history of postpartum depression. Am J Psychiatry 157(6):924–930

Boschloo L, Vogelzangs N et al (2011) Comorbidity and risk indicators for alcohol use disorders among persons with anxiety and/or depressive disorders: findings from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA). J Affect Disord 131(1–3):233–242

Boyd RC, Le HN et al (2005) Review of screening instruments for postpartum depression. Arch Womens Ment Health 8(3):141–153

Brugha T, Bebington P, Tennant C, Hurry J (1985) The list of threatening experiences: a subset of 12 life event categories with considerable long-term contextual treat. Psychol Med 15:189–194

Brugha T, Sharp H et al (1998) The Leicester 500 Project. Social support and the development of postnatal depressive symptoms, a prospective cohort survey. Psychol Med 28(01):63–79

Buist A (1998) Childhood abuse, parenting and postpartum depression. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 32(4):479–487

Campbell SB, Brownell CA et al (2004) The course of maternal depressive symptoms and maternal sensitivity as predictors of attachment security at 36 months. Dev Psychopathol 16(2):231–252

Costa PT Jr, McCrae RR (1995) Domains and facets: hierarchical personality assessment using the revised NEO personality inventory. J Pers Assess 64(1):21

Cox JL, Rooney A, Thomas PF, Wrate RW (1984) How accurately do mothers recall postnatal depression? Further data from a 3 year follow-up study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol 3(3–4):185–189

Cox JL, Holden JM et al (1987) Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry J Ment Sci 150:782–786

Cox JL, Murray D et al (1993) A controlled study of the onset, duration and prevalence of postnatal depression. Br J psychiatry J Ment sci 163:27–31

Donker T, Comijs H et al (2010) The validity of the Dutch K10 and extended K10 screening scales for depressive and anxiety disorders. Psychiatry Res 176(1):45–50

Dott M, Rasmussen S et al (2010) Association between pregnancy intention and reproductive-health related behaviors before and after pregnancy recognition, National Birth Defects Prevention Study, 1997–2002. Matern Child Health J 14(3):373–381

DSM-IV, Ed (1994) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV), 4th edn. American Psychiatric Association, Washington

Elliott S (2000) Report on the satra bruk workshop on classification of postnatal mental disorders on November 7–10, 1999. Convened by Birgitta Wickberg, Philip Hwang and John Cox. Arch Womens Ment Health 3:27–33

Feldman R, Granat A et al (2009) Maternal depression and anxiety across the postpartum year and infant social engagement, fear regulation, and stress reactivity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 48(9):919–927

Field T (2010) Postpartum depression effects on early interactions, parenting, and safety practices: a review. Infant Behav Dev 33(1):1–6

First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW (1995) Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV (SCID). American Psychiatric Association, Washington

Fleming AS, Corter C (1988) Factors influencing maternal responsiveness in humans: usefulness of an animal model. Psychoneuroendocrinology 13(1–2):189–212

Flynn HA, Davis M et al (2004) Rates of maternal depression in pediatric emergency department and relationship to child service utilization. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 26(4):316–322

Flynn HA, Sexton M et al (2011) Comparative performance of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 in pregnant and postpartum women seeking psychiatric services. Psychiatry Res 187(1–2):130–134

Fyer AJ, Weissman MM (1999) Genetic linkage study of panic: clinical methodology and description of pedigrees. Am J Med Genet 88(2):173–181

Gavin NI, Gaynes BN et al (2005) Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol 106(5 Pt 1):1071–1083

Gaynes BN, Gavin N et al (2005) Perinatal depression: prevalence, screening accuracy, and screening outcomes. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ) 119:1–8

Gigantesco A, Morosini P (2008) Development, reliability and factor analysis of a self-administered questionnaire which originates from the World Health Organization's Composite International Diagnostic Interview-Short Form (CIDI-SF) for assessing mental disorders. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health CP & EMH 4:8

Grimstad H, Backe B et al (1998) Abuse history and health risk behaviors in pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 77(9):893–897

Wittchen HU (1994) Reliability and validity studies of the WHO—Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): a critical review. J Psychiatr Res 28(1):57–84

Hewitt CE, Gilbody SM (2009) Is it clinically and cost effective to screen for postnatal depression: a systematic review of controlled clinical trials and economic evidence. BJOG 116(8):1019–1027

Kendall-Tackett KA (2007) Violence against women and the perinatal period: the impact of lifetime violence and abuse on pregnancy, postpartum, and breastfeeding. Trauma Violence Abuse 8(3):344–353

Kendler KS, Bulik CM et al (2000) Childhood sexual abuse and adult psychiatric and substance use disorders in women: an epidemiological and cotwin control analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 57(10):953–959

Kessler RC, Andrews G et al (2002) Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med 32(6):959–976

Kumar R, Robson KM (1984) A prospective study of emotional disorders in childbearing women. Br J psychiatry J Ment sci 144:35–47

Kupfer DJ, Frank E et al (2011) Major depressive disorder: new clinical, neurobiological, and treatment perspectives. Lancet 379(9820):1045–1055

Landman-Peeters KM, Hartman CA et al (2005) Gender differences in the relation between social support, problems in parent-offspring communication, and depression and anxiety. Soc Sci Med 60(11):2549–2559

Leeners B, Richter-Appelt H et al (2006) Influence of childhood sexual abuse on pregnancy, delivery, and the early postpartum period in adult women. J Psychosom Res 61(2):139–151

Leeners B, Stiller R et al (2010) Pregnancy complications in women with childhood sexual abuse experiences. J Psychosom Res 69(5):503–510

Leserman J (2005) Sexual abuse history: prevalence, health effects, mediators, and psychological treatment. Psychosom Med 67(6):906–915

Leserman J, Drossman DA et al (1996) Sexual and physical abuse history in gastroenterology practice: how types of abuse impact health status. Psychosom Med 58(1):4–15

Lindahl V, Pearson JL et al (2005) Prevalence of suicidality during pregnancy and the postpartum. Arch Womens Ment Health 8(2):77–87

Lukasse M, Vangen S et al (2011) Fear of childbirth, women's preference for cesarean section and childhood abuse: a longitudinal study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 90(1):33–40

Marmorstein NR, Malone SM et al (2004) Psychiatric disorders among offspring of depressed mothers: associations with paternal psychopathology. Am J Psychiatry 161(9):1588–1594

McCauley J, Kern DE et al (1997) Clinical characteristics of women with a history of childhood abuse: unhealed wounds. JAMA 277(17):1362–1368

Meltzer-Brody S, Zerwas S et al (2011) Eating disorders and trauma history in women with perinatal depression. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 20(6):863–870

Micali N, Simonoff E et al (2011) Pregnancy and post-partum depression and anxiety in a longitudinal general population cohort: the effect of eating disorders and past depression. J Affect Disord 131(1–3):150–157

Milgrom J, Gemmill AW et al (2008) Antenatal risk factors for postnatal depression: a large prospective study. J Affect Disord 108(1–2):147–157

Moffitt TE, Harrington H et al (2007) Depression and generalized anxiety disorder: cumulative and sequential comorbidity in a birth cohort followed prospectively to age 32 years. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64(6):651–660

Munk-Olsen T, Laursen TM et al (2006) New parents and mental disorders: a population-based register study. JAMA 296(21):2582–2589

Munk-Olsen T, Laursen TM et al (2011) Psychiatric disorders with postpartum onset: possible early manifestations of bipolar affective disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 69(4):428–434

Murray L, Cooper P (1997) Effects of postnatal depression on infant development. Arch Dis Child 77(2):99–101

Murray L, Stein A (1989) The effects of postnatal depression on the infant. Baillieres Clin Obstet Gynaecol 3(4):921–933

Network NECCR (1999) Chronicity of maternal depressive symptoms, maternal sensitivity, and child functioning at 36 months. Dev Psychol 35(5):1297–1310

Nurnberger JI Jr, Blehar MC et al (1994) Diagnostic interview for genetic studies: rationale, unique features, and training. Arch Gen Psychiatry 51(11):849–859

O'Connor TG, Zeanah CH (2003) Current perspectives on attachment disorders: rejoinder and synthesis. Attach Hum Dev 5(3):321–326

O'Hara MW (2009) Postpartum depression: what we know. J Clin Psychol 65(12):1258–1269

O'Hara MW, Swain AM (1996) Rates and risk of postpartum depression—a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry 8(1):37–54

Onoye JM, Goebert D et al (2009) PTSD and postpartum mental health in a sample of Caucasian, Asian, and Pacific Islander women. Arch Womens Ment Health 12(6):393–400

Paulson JF, Dauber S et al (2006) Individual and combined effects of postpartum depression in mothers and fathers on parenting behavior. Pediatrics 118(2):659–668

Penninx BW, Beekman AT et al (2008) The Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA): rationale, objectives and methods. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 17(3):121–140

Penninx BW, Nolen WA et al (2011) Two-year course of depressive and anxiety disorders: results from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA). J Affect Disord 133(1–2):76–85

Rahman A, Iqbal Z et al (2004) Impact of maternal depression on infant nutritional status and illness: a cohort study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 61(9):946–952

Records K, Rice MJ (2009) Lifetime physical and sexual abuse and the risk for depression symptoms in the first 8 months after birth. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 30(3):181–190

Robertson E, Grace S et al (2004) Antenatal risk factors for postpartum depression: a synthesis of recent literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 26(4):289–295

Romans S, Belaise C et al (2002) Childhood abuse and later medical disorders in women. An epidemiological study. Psychother Psychosom 71(3):141–150

Rubertsson C, Waldenström U et al (2003) Depressive mood in early pregnancy: prevalence and women at risk in a national Swedish sample. J Reprod Infant Psychol 21(2):113–123

Rubinow DR (2005) Reproductive steroids in context. Arch Womens Ment Health 8:1–5

Rubinow DR, Schmidt PJ (2006) Gonadal steroid regulation of mood: the lessons of premenstrual syndrome. Front Neuroendocrinol 27(2):210–216

Schmidt PJ, Nieman LK et al (1998) Differential behavioral effects of gonadal steroids in women with and in those without premenstrual syndrome. N Engl J Med 338(4):209–216

Silverman ME, Loudon H (2010) Antenatal reports of pre-pregnancy abuse is associated with symptoms of depression in the postpartum period. Arch Womens Ment Health 13(5):411–415

Smith MV, Shao L et al (2010) Perinatal depression and birth outcomes in a Healthy Start project. Matern Child Health J 15(3):401–409

Suellentrop K, Morrow B, Williams L, D'Angelo D (2006) Monitoring progress toward achieving Maternal and Infant Healthy People 2010 objectives—19 states, Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), 2000–2003. MMWR Surveill Summ 55(9):1–11

Tammentie T, Tarkka M-T et al (2002) Sociodemographic factors of families related to postnatal depressive symptoms of mothers. Int J Nurs Pract 8(5):240–246

Viguera AC, Tondo L et al (2011) Episodes of mood disorders in 2,252 pregnancies and postpartum periods. Am J Psychiatry 168(11):1179–1185

Warner R, Appleby L et al (1996) Demographic and obstetric risk factors for postnatal psychiatric morbidity. Br J Psychiatry 168(5):607–611

Wiersma J, Hovens JG, Oppen P, Giltay EJ, Schaik DV, Beekman AT, Penninx BW (2009) The importance of childhood trauma and childhood life events for chronicity of depression in adults. J Clin Psychiatry 70:983–989

Wisner KL, Parry BL et al (2002) Clinical practice. Postpartum depression. N Engl J Med 347(3):194–199

Wisner KL, Moses-Kolko EL et al (2010) Postpartum depression: a disorder in search of a definition. Arch Womens Ment Health 13(1):37–40

Wittchen H-U, Burke JD et al (1989) Recall and dating of psychiatric symptoms: test-retest reliability of time-related symptom questions in a standardized psychiatric interview. Arch Gen Psychiatry 46(5):437–443

Wittchen H, Robins L et al (1991) Cross-cultural feasibility, reliability and sources of variance of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). The Multicentre WHO/ADAMHA Field Trials. Br J Psychiatry 159(5):645–653 [published erratum appears in Br J Psychiatry 1992 Jan;160:136]

Yonkers KA, Ramin SM et al (2001) Onset and persistence of postpartum depression in an inner-city maternal health clinic system. Am J Psychiatry 158(11):1856–1863

Acknowledgments

The infrastructure of the NESDA study fully supported this project and provided the critical assistance to interview the subjects who generously gave their time to participate in this study. We thank Dr. John Cox, the creator of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, for his thoughtful review of the manuscript and willingness to allow us to modify the original version of the EPDS to assess lifetime episodes of perinatal depression.

The infrastructure for the NESDA study (www.nesda.nl) is funded through the Geestkracht program of the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (Zon-MW, grant number 10-000-1002) and is supported by participating universities and mental health care organizations (VU University Medical Center, GGZinGeest, Arkin, Leiden University Medical Center, GGZ Rivierduinen, University Medical Center Groningen, Lentis, GGZ Friesland, GGZ Drenthe, IQ Healthcare, Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research (NIVEL), and Netherlands Institute of Mental Health and Addiction (Trimbos)). Dr. Meltzer-Brody is funded by the National Institutes of Health grant # K23MH85165.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Meltzer-Brody, S., Boschloo, L., Jones, I. et al. The EPDS-Lifetime: assessment of lifetime prevalence and risk factors for perinatal depression in a large cohort of depressed women. Arch Womens Ment Health 16, 465–473 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-013-0372-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-013-0372-9