Abstract

Postpartum depression is a prevalent mental disorder; however, scarce research has examined its association with prenatal health behaviors. This study investigated the associations of cigarette smoking, caffeine intake, and vitamin intake during pregnancy with postpartum depressive symptoms at 8 weeks after childbirth. Using a prospective cohort study design, participants were recruited from the postpartum floor at a hospital for women and newborns located in a northeastern city, from 2005 through 2008. Eligible women who were at least 18 years old and spoke English were interviewed in person while hospitalized for childbirth (N = 662). A follow-up home interview was conducted at 8 weeks postpartum with a 79% response rate (N = 526). Hierarchical regression analyses showed that smoking cigarettes anytime during pregnancy and not taking prenatal vitamins in the first trimester were significantly associated with worse depressive symptoms (Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale). Moreover, having a colicky infant, an infant that refuses feedings, being stressed out by parental responsibility, and having difficulty balancing responsibilities were stressors associated with worse depressive symptoms. Primary health care providers should consider evaluating women for risk of postpartum depression during their first prenatal visit, identifying prenatal health behaviors such as smoking and taking prenatal vitamins.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Postpartum depression is a nonpsychotic depressive episode that occurs in the period after childbirth and negatively affects the mother’s quality of life (Beck 2002), her intimate relationships (Zelkowitz and Milet 1996), and infant emotional and cognitive development (Beck 1998; Grace et al. 2003). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV limits the onset of postpartum depression to the first 4 weeks after childbirth (American Psychiatric Association 2000); however, several epidemiological studies found that the first 3 months after childbirth bears the highest risk of postpartum depression (Andrews-Fike 1999; Horowitz and Goodman 2004; Stowe et al. 2005). A meta-analysis of 59 studies found the prevalence rate of postpartum depression to be approximately 13% (O'Hara and Swain 1996). Thus, this is a significant public health problem that warrants attention from primary care providers and clinicians. Postpartum depression received top priority at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ (ACOG) 58th Annual Clinical Meeting in 2010, where the president of ACOG called for more focus on the psychological health of prenatal and postnatal patients.

The research literature has shown factors such as depression history (Da Costa et al. 2000; Horowitz et al. 2005), social support (Beck 2001), stressful life events (Da Costa et al. 2000; Terry et al. 1996), breastfeeding (Astbury et al. 1994; Hannah et al. 1992), and infant temperament (Klein et al. 1998; Terry et al. 1996) to influence the risk of postpartum depression. However, scarce research has investigated the associations between prenatal health behaviors and postpartum depression. The proportion of women in the USA who engage in risky health behaviors during pregnancy is substantial. In 2003, approximately 11% of pregnant women reported smoking during pregnancy (Martin et al. 2005), and 10% reported drinking alcohol (Centers for Disease Control 2002).

A few studies examined the relationships between smoking and perinatal depression. A study of 552 Norwegian women found that current smokers and former smokers had a higher likelihood of being depressed (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale—CES-D) during pregnancy than never smokers (Zhu and Valbo 2002). Another study of 3,472 pregnant women in southeastern Michigan revealed that women who smoked a greater number of cigarettes per day had a higher likelihood of having an elevated CES-D (Marcus et al. 2003). One study that used Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System data on 2,566 women who smoked during the 3 months before pregnancy and quit during pregnancy found that women with postpartum depressive symptoms were 1.77 times likely to relapse than women with no symptoms (Allen et al. 2009). Another study interviewed 217 women who gave birth at three sites in Oklahoma State University (Breese McCoy et al. 2006). Results showed that smokers had a higher likelihood of being depressed at 4 months postpartum (threshold score of 13 on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale—EPDS) than nonsmokers (RR = 1.58). Similarly, a pilot study interviewed 96 women who brought their babies to the 8-week well-baby visit at the University of Arizona and found that mothers who reported smoking had higher EPDS scores (Freeman et al. 2005). Most of these studies focused on depression during pregnancy, and those that focused on postpartum depression (Breese McCoy et al. 2006; Freeman et al. 2005) employed small sample sizes.

The literature on prenatal vitamins use and postpartum depression is scarce. Vitamin B6 has been theoretically linked to depression as a cofactor in the tryptophan–serotonin pathway (Hvas et al. 2004). One study examined 24 women with postpartum depression and compared their vitamin B6 levels to those of 40 nonpregnant women of reproductive age, 30 pregnant women, and 20 postpartum not depressed women (Livingston et al. 1978). Results showed no significant differences between women with postpartum depression and the control groups. A Japanese study obtained dietary data during pregnancy by administering a diet history questionnaire to 865 women from Osaka (Miyake et al. 2006). No significant associations were found between intake of vitamin B9, vitamin B12, or vitamin B6 and postpartum depression between 2 and 9 months postpartum. Vitamin B2 intake in the third quartile of pregnancy was associated with decreased risk of postpartum depression as compared with intake in the first quartile (Miyake et al. 2006).

To date, no studies have examined the association between caffeine intake and postpartum depression but the general literature supports a positive association between caffeine and depression (Rogers et al. 2006; Veleber and Templer 1984). A review article posited two possible explanations for this association, one posits that depressed individuals drink more caffeine to deal with their depression and the second argues that caffeine causes mood changes (Broderick and Benjamin 2004). Biologically, it takes 3 to 6 h for half of the caffeine consumed to be excreted from the body for regular adults but it takes significantly longer time for pregnant women (Ortweiler et al. 1985; Rogers 2007). However, a recent article by Lucas et al. (2011) showed a dose–response relationship between caffeinated coffee and depression, whereby an increase in coffee consumption was associated with decreased risk of depression in a large cohort of US female registered nurses followed from 1996 to 2006. This study investigated the associations of cigarette smoking, caffeine intake, and vitamin intake during pregnancy with postpartum depression at 8 weeks after childbirth.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

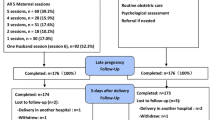

This prospective cohort study was conducted from 2005 through 2008. Participants were recruited from the postpartum floor at a university hospital for women and newborns located in a mid-size northeastern city, one of two “birthing” hospitals in the state. The study population consisted of all women delivering at this hospital. To be eligible, mothers had to be at least 18 years of age, speak English, and agree to sign the consent form. Since the original study aim was to examine prenatal smoking and infantile gastrointestinal dysregulation, participants were recruited according to smoking status (in a 1:2 smoker to nonsmoker ratio) to maximize statistical power. Eligible women were interviewed in person at the hospital within 24 h of giving birth. Out of the 932 women approached, 662 (71%) agreed to participate in hospital interviews. A follow-up home interview was conducted 8 weeks postpartum with a 79% response rate (N = 526). A well-trained research assistant recruited and interviewed all respondents.

Data and measures

Data were collected using hospital interviews around birth and home interviews at approximately 8 weeks after childbirth (mean = 8; SD = 1.4). After approval from institutional review boards, data were abstracted from the labor and delivery record sheet and interviews were conducted utilizing structured questionnaires that used measures with established reliability and validity.

The dependent variable was measured as a continuous score using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) administered at approximately 8 weeks postpartum (Cox et al. 1987). This scale consists of ten short statements about how the mother felt during the past 7 days, with four response categories ranging from 0 to 3. The EPDS was initially presented as a unidimensional scale for detection of postpartum depression (Cox et al. 1987). However, more recent work with the scale (Brouwers et al. 2001; Ross et al. 2003) indicated that the item inquiring about suicide can be considered an independent factor and should be excluded from the scale. Therefore, we assessed all EPDS items with the exception of item 10 that asks about suicidal thoughts.

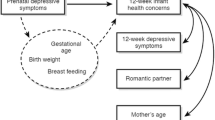

Based on a priori causal assumptions, several covariates pertaining to personal and perinatal factors that could confound the relationship between prenatal health behaviors and postpartum depression were included as control variables. Moreover, it was important to include stress-related factors in the model as the literature has shown these factors to be consistent risk factors in the etiology of postpartum depression. The control and independent variables included measures of personal characteristics, perinatal factors, stress-related factors, and prenatal health behaviors. A summary of these measures and their coding is presented in Table 1.

Results

Participants were on average 28 years old, 46% were married, 31% had a college degree, and 76% were white (Table 2). Thirty-eight percent of the women smoke cigarettes, 62% drank coffee, 68% drank soda, 28% drank tea, and 81% took prenatal vitamins during their pregnancy. Approximately 6.5% (n = 30) of the women met the threshold for depression at 8 weeks postpartum.

Table 3 summarizes the hierarchical regression analysis results.Footnote 1 Model 1 reveals that control variables explained 8% of the variance in postpartum depression scores. In model 2, exposure to second hand smoking during pregnancy had no association with postpartum depression scores whereas smoking cigarettes anytime during pregnancy was positively associated with these scores.Footnote 2 Smoking variables in model 2 explained an additional 5% of the variance in depression scores. In model 3, only vitamin use in the first trimester of pregnancy had a significant negative relationship with postpartum depression scores. In model 4, caffeine use during pregnancy was not associated with postpartum depression scores.Footnote 3 Model 5 showed positive associations between stress variables related to parental responsibility and postpartum depression scores, where increased stress was associated with higher depression scores. These stress variables explained an additional 13% of the variance. In model 6, having a colicky infant and an infant that refuses feedings were both positively associated with postpartum depression scores and explained an additional 3% of the variance. As can be seen in models 2 through 6, there was a consistent statistically significant association between prenatal smoking and postpartum depressive symptoms (p < 0.001).

Discussion

In this study, we found an association between prenatal smoking and worse depressive symptoms 8 weeks after delivery. These results are consistent with the literature on smoking and perinatal depression (Breese McCoy et al. 2006; Freeman et al. 2005; Zhu and Valbo 2002). Women who had smoked anytime during pregnancy scored 2.34 points higher on the postpartum depression scale than women who had not smoked (coefficients ranged between 2.34 and 1.74 in models 2 through 6). Matthey (2004) calculated the reliable change index for the EPDS and found that a score change of at least 4 points is clinically significant. Thus, the difference in scores between prenatal smokers and nonsmokers may not be clinically significant. Due to the cross-sectional study design, it is possible that depressed women use smoking as a self-medication mechanism or alternatively that smoking results in mood changes. Nevertheless, primary care providers may consider smoking during pregnancy as a marker for potential vulnerability for postpartum depression. In 2010, the ACOG issued recommendations encouraging providers to support perinatal smoking cessation starting with the first prenatal visit, an additional incentive for providers to inquire about prenatal smoking behaviors (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2010).

Taking prenatal vitamins, specifically during the first trimester, was associated with lower postpartum depressive symptoms. It may be that prenatal vitamin intake in the first trimester acts as a proxy for whether the pregnancy was planned or wanted (Hellerstedt et al. 1998). Future studies should investigate whether having a planned pregnancy mediates the association between prenatal vitamin intake during the first trimester and maternal postpartum depression or if there are biological reasons for this association.

Feeling stressed by parental responsibility and perceiving difficulty in balancing different parenting responsibilities, both were factors associated with worse postpartum depression scores. A consistent finding in the literature has been that stressful life events happening closely before or after delivery are positively associated with postpartum depression (Da Costa et al. 2000; Terry et al. 1996). The birth of a baby brings new challenges to a woman’s life including integrating a new family member’s demands into already existing demands. Giving birth to a new child has been found to be associated with marital problems and lower quality of intimate relationships (Von Sydow 1999). Moreover, changes in a woman’s appraisal of herself, her body image (Fox and Yamaguchi 1997), and changes in her social role as a new mother are all stressors that may increase her risk of postpartum depression.

Having an infant with crying or fussiness problems and an infant who refuses feedings even when hungry, both were associated with worse depressive symptoms. These findings are consistent with the postpartum depression literature on infant temperament (Beck 2001; McGrath et al. 2008). However, this study adds to the literature by introducing a new aspect of infant temperament, refusal of feedings. One study found a significant association between maternal depressive symptoms and each of forceful, indulgent, and uninvolved feeding styles (Hurley et al. 2008). This may be one explanation for our findings; however, it may be that having an infant who refuses feedings is a stressor that influences women’s risk of postpartum depression.

Our study had limitations pertaining to participants, measures, and methods. First, findings can mainly be generalized to women with similar demographic characteristics as this sample since these women were recruited from a single hospital site. Second, postpartum depression was measured by self-report and not validated by medical diagnoses; thus, findings pertain to postpartum depressive symptoms. Third, we did not have data on the support of the family members or the husband. Finally, the cross-sectional measurement of study variables precluded causal inferences.

Strengths of this study include its large sample size, the use of survey questions from established validated instruments, and the employment of a sophisticated multivariate statistical technique in data analyses. Moreover, this study investigated the relationships between prenatal health behaviors and postpartum depressive symptoms, an important contribution to the postpartum depression literature.

Conclusion

This study found that smoking anytime during pregnancy and not taking prenatal vitamins during the first trimester were associated with higher postpartum depressive symptoms, whereas prenatal caffeine intake was not associated with depressive symptoms. Primary healthcare providers and clinicians should consider evaluating women for risk of postpartum depression during their first prenatal visit, identifying prenatal health behaviors such as smoking and taking prenatal vitamins. They may also want to consider monitoring these behaviors over the women’s prenatal period during regular checkups. Future research should investigate the mechanisms that mediate the associations of smoking cigarettes and prenatal vitamin intake with postpartum depression and explore the influence of other prenatal health behaviors such as alcohol intake, drug use, and exercise.

Notes

Hierarchical regression builds successive linear regression models, where each model adds more predictors and the change in R 2 is calculated. This type of regression was used because the literature is scarce on the relationships examined.

Due to the potential problem of multicollinearity, we could not run a regression analysis that included whether or not the woman smoked during pregnancy in addition to the number of cigarettes smoked. However, we ran an alternative regression that included the maximum number of cigarettes smoked at each trimester of pregnancy but none of the variables had a significant association with postpartum depressive symptoms (results available upon request).

We conducted an alternative regression analysis utilizing dose of caffeine instead of whether the women drank caffeine during pregnancy, and this variable did not show a significant association with postpartum depressive symptoms either. We constructed this variable by categorizing women into those who did not drink caffeine at all, drank one source of caffeine, drank two sources of caffeine, or drank three sources of caffeine. Sources of caffeine included soda, coffee, and tea (results available upon request).

References

Allen AM, Prince CB, Dietz PM (2009) Postpartum depressive symptoms and smoking relapse. Am J Prev Med 36:9–12

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2010) Committee opinion no. 471: smoking cessation during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 116(5):1241–1244

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ (2010) 58th Annual Clinical Meeting (ACM), May 15–19, 2010. http://www.acog.org/acm/acmflyer/acm2010booklet.pdf. Accessed 05 July 2011

American Psychiatric Association (2000) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. American Psychiatric Association, Washington

Andrews-Fike C (1999) A review of postpartum depression. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 1(1):9–14

Astbury J, Brown S, Lumley J et al (1994) Birth events, birth experiences and social differences in postnatal depression. Aust J Public Health 18:176–184

Beck CT (1998) The effects of postpartum depression on child development: a meta-analysis. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 12:12–20

Beck CT (2001) Predictors of postpartum depression: an update. Nurs Res 50(5):275–285

Beck CT (2002) Postpartum depression: a metasynthesis. Qual Health Res 12(4):453–472

Breese McCoy SJ, Beal JM, Miller Shipman SB et al (2006) Risk factors for postpartum depression: a retrospective investigation at 4 weeks postnatal and a review of the literature. J Am Osteopath Assoc 106:193–198

Broderick P, Benjamin AB (2004) Caffeine and psychiatric symptoms: a review. J Okla State Med Assoc 97:538–542

Brouwers EP, Van Baar AL, Pop VJ (2001) Does the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale measure anxiety? J Psychosom Res 51:659–663

Brown R, Burgess E, Sales S et al (1998) Reliability and validity of a smoking timeline follow-back interview. Psychol Addict Behav 12:101–112

Centers for Disease Control (2002) Alcohol consumption among women who are pregnant or who might become pregnant—United States, 2002. MMWR 53:1178–1181

Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R (1987) Detection of postnatal depression: development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry 150:782–786

Da Costa D, Larouche J, Dritsa M et al (2000) Psychosocial correlates of prepartum and postpartum depressed mood. J Affect Disord 59:31–40

Fox P, Yamaguchi C (1997) Body image change in pregnancy: a comparison of normal weight and overweight primigravidas. Birth 24:35–40

Freeman MP, Wright R, Watchman M et al (2005) Postpartum depression assessments at well-baby visits: screening feasibility, prevalence, and risk factors. J Womens Health 14:929–935

Grace SL, Evindar A, Stewart DE (2003) The effect of postpartum depression on child cognitive development and behavior: a review and critical analysis of the literature. Arch Womens Ment Health 6(4):263–274

Hannah P, Adams D, Lee A et al (1992) Links between early postpartum mood and postnatal depression. Br J Psychiatry 160:777–780

Hellerstedt WL, Pirie PL, Lando HA et al (1998) Differences in preconceptual and prenatal behaviors in women with intended and unintended pregnancies. Am J Public Health 88(4):663–666

Horowitz JA, Goodman J (2004) A longitudinal study of maternal postpartum depression symptoms. Res Theory Nurs Pract 18:149–163

Horowitz J, Damato L, Duffy M et al (2005) The relationship of maternal attributes, resources and perceptions of postpartum experiences to depression. Res Nurs Health 28:159–171

Hurley KM, Black MM, Papas MA et al (2008) Maternal symptoms of stress, depression, and anxiety are related to non-responsive feeding styles in a statewide sample of WIC participants. J Nutr 138:799–805

Hvas AM, Juul S, Bech P et al (2004) Vitamin B6 level is associated with symptoms of depression. Psychother Psychosom 73(6):340–343

Klein MH, Hyde JS, Essex MJ et al (1998) Maternity leave, role quality, work involvement, and maternal health one year after delivery. Psychol Women Q 22:239–266

Lester BM, Boukydis CFZ, Garcia-Coll CT et al (1992) Infantile colic: acoustic cry characteristics, maternal perception of cry, and temperament. Infant Behav Dev 15:15–26

Livingston JE, MacLeod PM, Applegarth DA (1978) Vitamin B6 status in women with postpartum depression. Am J Clin Nutr 31:886–891

Lucas M, Mirzaei F, Pan A et al (2011) Coffee, caffeine, and risk of depression among women. Arch Intern Med 171:1571–1578

Marcus SM, Flynn HA, Blow FC et al (2003) Depressive symptoms among pregnant women screened in obstetrics settings. J Womens Health 12(4):373–380

Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD et al (2005) Births: final data for 2003. Natl Vital Stat Rep 54(2):1–116, National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville

Matt GE, Hovell MF, Zakarian JM et al (2000) Measuring secondhand smoke exposure in babies: the reliability and validity of mother reports in a sample of low-income families. Health Psychol 19(3):232–241

Matthey S (2004) Calculating clinically significant change in postnatal depression studies using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. J Affect Disord 78:269–272

McGrath JM, Records K, Rice M (2008) Maternal depression and infant temperament characteristics. Infant Behav Dev 31(1):71–80

Miyake Y, Sasaki S, Tanaka K et al (2006) Dietary folate and vitamins B(12), B(6), and B(2) intake and the risk of postpartum depression in Japan: the Osaka Maternal and Child Health Study. J Affect Disord 96(1–2):133–138

National Center for Health Statistics Educational Differences in Health Status and Health Care (1991) Data from the National Health Interview Survey, US, 1989. Vital and Health Statistics. Series 10, No 179. DHHS Pub. NO (PHS) 91-1507. Public Health Service, Washington, US GPO

O'Hara MW, Swain AM (1996) Rates and risk of postpartum depression: a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry 8:37–54

Ortweiler W, Simon HU, Splinter FK et al (1985) Determination of caffeine and metamizole elimination in pregnancy and after delivery as an in vivo method for characterization of various cytochrome p-450 dependent biotransformation reactions. Biomed Biochim Acta 44(7–8):1189–1199, Article in German

Reitman D, Currier RO, Stickle TR (2002) A critical evaluation of the Parenting Stress Index-Short Form (PSI-SF) in a Head Start population. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 31(3):384–392

Rogers PJ (2007) Caffeine, mood and mental performance in everyday life. Nutr Bull 32(suppl 1):84–89

Rogers PJ, Heatherley SV, Mullings EL et al (2006) Licit drug use and depression, anxiety and stress. J Psychopharmacol 20:A27

Ross LE, Gilbert Evans S, Sellers EM et al (2003) Measurement issues in postpartum depression part 1: anxiety as a feature of postpartum depression. Arch Womens Ment Health 6:51–57

Stowe ZN, Hostetter AL, Newport DJ (2005) The onset of postpartum depression: implications for clinical screening in obstetrical and primary care. Am J Obstet Gynecol 192(2):522–526

Terry DJ, Mayocchi L, Hynes GJ (1996) Depressive symptomatology in new mothers: a stress and coping perspective. J Abnorm Psychol 105(2):220–231

US Census Bureau (2001) Overview of Race and Hispanic Origin Census 2000 (C2KBR/01-1). US Department of Commerce, US Census Bureau, Washington

Veleber DM, Templer DI (1984) Effects of caffeine on anxiety and depression. J Abnorm Psychol 93:120–122

Von Sydow K (1999) Sexuality during pregnancy and after childbirth: a metacontent analysis of 59 studies. J Psychosom Res 47:27–49

Ware J, Kosinski M, Turner-Bowker D et al (2002) Version 2 of the SF-12 Health Survey. QualityMetric Inc., Lincoln

Zelkowitz P, Milet TH (1996) Postpartum psychiatric disorders: their relationship to psychological adjustment and marital satisfaction in the spouses. J Abnorm Psychol 105(2):281–285

Zhu S-H, Valbo A (2002) Depression and smoking during pregnancy. Addict Behav 27(4):649–658

Funding

This publication was supported by Grant #R40MC03600-01-00 from the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Department of Health and Human Services. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Maternal and Child Health Bureau.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors report no conflict of interest with regards to this manuscript

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Prior presentation of this paper is in a study entitled “Prenatal health behaviors and postpartum depression: Is there an association?” by R. Dagher with E. Shenassa (poster presentation), Academy Health Annual Research Meeting, Boston, MA, June 27–29, 2010 (also presented at the Gender and Health Interest Group session, June 26, 2010).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dagher, R.K., Shenassa, E.D. Prenatal health behaviors and postpartum depression: is there an association?. Arch Womens Ment Health 15, 31–37 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-011-0252-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-011-0252-0