Abstract

This study aimed at estimating the prevalence of postpartum depression (PPD) according to postpartum periods and sub-groups in public primary health care settings in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. A cross-sectional survey was carried out in five primary health care units and included 811 participants randomly selected among mothers of children up to five postpartum months. Women were classified as depressed and given scores on Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) above 11. The overall estimate of PPD was 24.3% (95% CI, 21.4–27.4). However, estimates were not homogeneous during the first 5 months postpartum (p value = 0.002). There was a peak of depressive symptoms around 3 months postpartum, when 128 women (37.5%, 95% CI, 29.1–46.5) disclosed scores above 11 on EPDS. Regarding the magnitude of PPD according to some maternal and partners' characteristics, it was consistently higher among women with low schooling, without a steady partner, and whose partners misused alcohol or used illicit drugs. The prevalence of PPD among women attending primary health care units in Rio de Janeiro seems to be higher than general estimates of 10–15%, especially among mothers with low schooling and that receive little (if any) support from partners. Also, the “burden” of PPD may be even higher around 3 months postpartum. These results are particularly relevant for public health policies. Evaluation of maternal mental health should be extended at least until 3 to 4 months postpartum, and mothers presenting a high-risk profile deserve special attention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Postpartum depression (PPD) is a common and rather serious postpartum disorder (Gjerdingen and Yawn 2007; WHO and UNFPA 2009). Besides the dire consequences to her own health (WHO and UNFPA 2009), depression in a mothering woman directly affects her entire family. Partners of women who present PPD are more prone to clinical depression, which further contributes to the strain in marital relationships (Halbreich and Karkun 2006). Moreover, PPD is associated with different harmful infant outcomes, such as cognitive and social developmental delays (Grace et al. 2003), sleeping disorders (Hiscock and Wake 2001), and physical and psychological illnesses (Hammen and Brennan 2003; Rahman et al. 2007). Therefore, PPD is a key issue concerning maternal and child health (Gjerdingen and Yawn 2007; WHO and UNFPA 2009).

Albeit viewed as a public health problem, the magnitude of PPD is largely conflicting and elusive. Different researchers have suggested an overall prevalence ranging from 10% to 15% (O'Hara and Swain 1996). However, these figures need to be viewed cautiously, since cultural, ethnic, socio-economic, and biological factors may play a part in the magnitude of PPD in a given population (Halbreich and Karkun 2006). Discrepant estimates may also be attributable to different study designs and measurement tools, as well as convenience samples. In addition, population-based or hospital-based studies may render different pictures, and the severity of depressive symptoms may vary according to study populations. All these issues may also be accountable for some of the heterogeneous PPD prevalence estimates found in Brazilian studies, which range from 12% to 37% (Santos et al. 1999; Faisal-Cury et al. 2004; Moraes et al. 2006; Ruschi et al. 2007; Hasselmann et al. 2008).

In view of these discordant figures across studies, Halbreich and Karkun (2006) point toward the need for more customized approaches in the evaluation of maternal mental health. The recognition of specific magnitudes, risk groups, and setting diversities are essential to the implementation of more effective strategies for the prevention, early detection, and adequate management of depressed mothers. Thus, this study explicitly aims at estimating the prevalence of women presenting postpartum depression in public primary health care settings of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Besides assessing once again a general estimate, the study takes a step further and also looks into the differentials across the first 5 months postpartum, according to some maternal socio-demographic and reproductive characteristics and partners' substance use.

Material and methods

This is a descriptive, cross-sectional study carried out in five public primary health care units of the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, from January to June 2007. These units were located throughout the city and attended, primarily, a clientele dwelling in adjacent areas. Regarding the characteristics of this population, there is a predominance of young adult mothers with low education and a high proportion of first-time mothers (Castro et al. 2009). In addition, these health facilities provide assistance through spontaneous demand or scheduled consultations in pediatrics, internal medicine, gynecology, and obstetrics. Minor surgical procedures, vaccinations, and general actions for health promotion are also offered. Each unit performed, on average, 1,300 pediatric consultations per month at the time of data collection.

Participants were randomly selected among mothers of children up to 5 months postpartum who were waiting for pediatric or routine child care visits. Every day shift, a list of children up to 5 months of age was prepared before the start of the consultations. In sequence, a draw was carried out in order to determine which mother would be interviewed first. Following each interview, the list was redone, and another draw was taken. In view of other shared research purposes, women were considered ineligible when experiencing less than 1 month of intimate relationship with a partner during pregnancy or postpartum period, gave birth to twins, or when there was an absolute contraindication for breastfeeding. Face-to-face interviews took place in a private place following a free and informed consent. Eight hundred and fifty-three women were invited to participate in the study. Eighteen (2.1%) were not eligible, and 24 (2.8%) refused to participate, totaling 811 participants.

Postpartum depressive symptoms were assessed through the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) (Cox et al. 1987), the most widely used instrument as an approximation to PPD (Halbreich and Karkun 2006). It covers a woman's experience in the last 7 days, not just how the woman felt at the day of the interview. Different thresholds have been suggested for indication of probable PPD across the several studies carried out to validate the EPDS in different countries worldwide (Gibson et al. 2009). According to the first study on the cross-cultural adaptation of the Portuguese version of the EPDS, the 11⁄12 cutoff showed the best accuracy among Brazilian women (Santos et al. 1999) and was thus used in the present study. Maternal schooling was evaluated by years of education, and the Brazilian Economic Classification Criterion (ABEP 2003) was chosen to evaluate socio-economic status. Classes “A” and “B” were defined as high socio-economic statuses; class “C,” as medium socio-economic status; and classes “D” and “E”, low socio-economic statuses. Mothers were classified as adolescents if they were under 20 years old at the time of the interview, and steady partner was defined for mothers reporting the same spouse during the pregnancy and postpartum period. Breastfeeding was classified through 24-h recall, and premature birth was defined by birth below 37 gestational weeks. Brazilian-validated versions of worldwide-accepted instruments were employed to evaluate substance use by partners, both related to their respective partners by proxy. Alcohol use was evaluated by CAGE (cut-down, annoyed, guilty, eye-opener) (Mayfield et al. 1974; Masur and Monteiro 1983; Ewing 1984), and a cutoff point of two or more positive answers defined alcohol misuse. A Portuguese (Brazilian) version of the Non-Student Drugs Use Questionnaire was used to identify partner use of illicit drugs (Smart et al. 1981).

The software Stata 10 (StataCorp 2007) was used for data processing and analysis. Confidence intervals for proportions assumed binomial distributions. Fisher's exact test was employed to test homogeneity of estimates of PPD across sub-groups and time frames. Postpartum time was grouped into 30-day strata, except for the extreme strata, which was composed of 15 days. Thus, midpoints of the intermediate periods correspond to the end of the first (16–45 days), second (46–75), third (76–105), and fourth months (106–135 days) following delivery. A locally weighted ordinary least squares regression (Hastie and Tibshirani 1990) was employed to obtain a smooth curve fitting of the prevalence trend along the covered period.

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Rio de Janeiro Municipal Health Department in conformity with the principles embodied in the declaration of Helsinki, and a written informed consent was provided to all participants.

Results

The study population was predominantly composed of adult women (77.3%; 95% CI, 73.8–79.7), and mean maternal age was 25.3 (CI 95%, 24.9–25.8). Most of them had steady partners (86.6%; 95% CI, 83.9–88.7), and half (49.6%; 95% CI, 46.1–53.0) were first-time mothers. Most of them had up to 12 years of schooling (71.9%; 95% CI, 68.8–75.0) and belonged to low (42.5%; 95% CI, 39.1–46.0) or medium (45.6%; 95% CI, 42.1–49.1) socio-economic classes. Additionally, 16.3% (95% CI, 14.4–19.7) of the women reported less than six antenatal visits; 8.5% (95% CI, 6.7–10.6) had premature birth, and 47.8% (95% CI, 44.1–55.2) did not persist on exclusive breastfeeding after 5 months postpartum. In regard to the life habits of their partners, 23.1% (95% CI, 20.1–26.1) misused alcohol, and 12.9% (95% CI, 10.7–15.4) used illicit drugs.

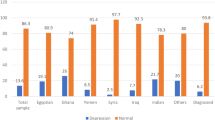

The overall prevalence estimate of PPD throughout the first 5 months postpartum was 24.3% (95% CI, 21.4–27.4). However, as shown in Fig. 1, this estimate was not homogeneous along the target postpartum period (p value = 0.002). A peak of depressive symptoms occurred around 3 months postpartum (76–105 day interval; average, 90 days), when 37.5% (95% CI, 29.1–46.5) of women disclosed scores above 11 on the EPDS.

Table 1 displays the estimates of PPD in the study population as a whole, separately for the period around the third postpartum month, as well as according to some sub-groups. In the total sample, the prevalence of women presenting scores above 11 was significantly higher among women with low schooling, pertaining to low socio-economic status, adolescents, without a steady partner, with insufficient attendance to antenatal care, not experiencing exclusive breastfeeding at the interview, and whose partners made misuse of alcohol or used illicit drugs. Around 3 months postpartum, the magnitude of PPD exceeded 50% in some sub-groups, and despite of the small sample size for the period, estimates of the prevalence of PPD were significantly higher among women with low schooling, without a steady partner, and whose partners misused alcohol or used illicit drugs.

Discussion

As indicated, the prevalence rates of PPD in the general population have been shown to range from 10% to 15% (O'Hara and Swain 1996). Nonetheless, these figures are unlikely to hold universally (Halbreich and Karkun 2006), since PPD and other postpartum disorders are heavily influenced by individual and group characteristics (Halbreich and Karkun 2006). In this perspective, this study adds to the knowledge on the magnitude of PPD in public primary health care in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Here, the general prevalence of PPD seems to exceed 20%, and the “burden” of maternal symptoms of depression tended to be even higher around 3 months postpartum. Also, the prevalence of women presenting scores on EPDS above 11 was consistently higher among some underprivileged groups, especially women with low schooling, without a steady marital relationship, or whose partners misused alcohol or used illicit drugs.

Although the overall prevalence of women with high levels of postpartum depressive symptoms in this study population was higher than the above-mentioned general prevalence (O'Hara and Swain 1996), the results did not significantly differ from those of other Brazilian studies. Hasselmann et al. (2008), studying mothers up to twenty postpartum days attending four public primary health care units of Rio de Janeiro, classified 22.5% of them as depressed. Moraes et al. (2006) uncovered comparable rates around 45 postpartum days (19.1%) in a population-based study carried out in the south of Brazil (Pelotas). These higher rates detected in some Brazilian settings may be explained by the population profile, which is largely composed of mothers with low education, adolescents, belonging to lower socio-economic classes, and that receive poor social support.

However, the rates of women presenting high levels of depressive symptoms were far from constant along the study period. Although some previous reports (Halbreich and Karkun 2006; Jadresic et al. 2007) have already suggested that the magnitude of PPD may vary during the first months after childbirth, the current findings provide empirical evidence that PPD is considerably more prevalent around 3 months postpartum. A peak of depressive symptoms close to 3 months after birth may, in fact, reveal a response to the cessation (or reduction) of general postnatal support and to the difficulties of dealing with the realities of motherhood (Halbreich and Karkun 2006). Regardless, the results point to the need for comprehensive maternal mental health evaluations around 3 to 4 months after birth. They also call for a reevaluation of the definitions currently employed to characterize postpartum mental disorders (Wisner et al. 2010). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 4th Version, sets 4 weeks postbirth as the delimiter to “postpartum onset,” whereas the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision, classifies mental disorders as “associated with the puerperium” if they begin within 6 weeks after childbirth. Thus, either of these two definitions fails to consider as “postpartum depression” cases that initiate around and beyond the second month, which does not seem to be adequate from a clinical and epidemiological perspective (Kendell et al. 1987). Perhaps, the time frame for identifying PPD should be extended to at least 3 months after delivery (Elliott 2000).

Finding far higher prevalence rates of PPD in some sub-groups is worth highlighting, since these figures were around 40% in the total sample among women without a steady partner, those with a poor history of antenatal care, and whose partners were substance abusers of one form or another. In women living without a steady partner or those whose partners made use of illicit drugs, the prevalence of probable depression exceeded 70%. These findings may be quite useful to guide actions addressing PPD in such units, especially in less-privileged settings. Despite the controversies on the adequacy of a widespread assessment of maternal mental health (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2010), in underprivileged locations, the available resources would be better directed to mothers under high risk of PPD. Women with low social support, especially those lacking effective support from their partners, seem to be especially vulnerable and should thus receive special attention from professionals involved in maternal–child care.

The results of this study must be seen in the light of their strengths and weaknesses. On the positive side stand the quality of the information on PPD and other variables of interest, which were evaluated by means of worldwide-accepted and validated instruments. Additionally, the relatively large sample size allowed investigating the prevalence of depressive symptoms across different time frames and sub-groups, which seemed to be essential to manage postpartum mood disorders (Halbreich and Karkun 2006). A potential drawback was the non-random selection of the five health facilities. However, the rationale for this option was to have units that offered solid conditions for the fieldwork, especially with regard to the amount of children available for sampling per day, as well as the physical structure of the settings so as to allow interviews to be carried out in a private and friendly atmosphere. Regardless, these health units covered quite large and geographically diverse areas of the city, and the socio-demographic profile of the study population was fairly similar to that found in a recent study encompassing a representative sample of primary health care units of the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro (Castro et al. 2009). Thus, the study population seems to provide a proper representation of what arises in general primary health care settings in the city and, perhaps, in similar services of other medium- to large-sized cities of Brazil. Yet, these results should not be uncritically extrapolated to the general population. As discussed earlier, population-based or hospital-based studies on PPD may involve fairly different magnitudes and severity profiles.

In view of the study's design and methodology, the results should not be strictly interpreted as the true prevalence of postpartum depression. Actually, true prevalence of PPD would be better evaluated through clinical interviews, recognizably the reference standard to diagnose depressive disorders. Recently, Matthey (2010) criticized most of the studies concerning the magnitude of PPD. According to the author's view, these studies consistently overestimate the scale of postpartum mood disorders, given that the estimates of PPD are usually based on the percentages of women scoring high on self-reporting measures such as the EPDS. In fact, the EPDS was originally envisaged as a device for a first approach to assess the maternal mental health problems and PPD in particular (Cox et al. 1987; Cox and Holden 2003). These authors suggested that mothers with high EPDS scores should be reevaluated in 2–3 weeks through a new application of the scale. Should a high score recur, the woman would then be assessed using a structured clinical interview for a definitive diagnosis of PPD (Cox and Holden 2003).

Matthey (2010) also criticizes the EPDS for its low positive predictive value—close to 50%, pointing out that this may hinder its use as a proxy for a clinical diagnosis of PPD. However, it must be pointed out that this judgment was based upon an average of just four validation studies, and above all, it was heavily influenced by one larger study involving a low-risk population for PPD (Murray and Carothers 1990). Since the positive predictive value tends to increase with the magnitude of an event, the situation may more auspicious in the current high-risk, high-prevalence setting. The prevalence of PPD estimated through the EPDS in the present study may thus be quite robust and consistent with similar studies conducted in Brazil where the rates of PPD were also high.

Success in the prevention of postpartum mental health disorders would benefit from a comprehensive approach. Although there is insufficient evidence to support a firm recommendation for universal screening of PPD (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2010), several vulnerable population groups have been identified and should be consistently focused on (O'Hara and Swain 1996; Robertson et al. 2004). The overall “burden” of PPD among women attending primary public health care units in Rio de Janeiro seems to be higher than 20%, which justifies priority actions in the context of maternal and child public health policies. In addition, it is crucial that underprivileged women receive even more attention, especially those with low education and/or who receive little, if any, social support from partners, since PPD seems to be common among them. Yet, in view of the higher rates of PPD around 3 months postpartum, it would be unwise to restrict maternal mental health assessments to the regular follow-up appointments, which are usually scheduled at the first 4–6 weeks after birth. Although many cases occurring at the peak period may well insidiously initiate within a few days or weeks of delivery, several others come about much later. Consequently, these cases would hardly be detected with the current arrangements where obstetric and pediatric services are poorly integrated. According to this perspective, screening of maternal depression in general pediatric outpatient clinics has been recently advocated on the recognition that regular pediatric visits scheduled for the first year after birth comprise unique opportunities to address both mothers and infants at once (Chaudron et al. 2004).

References

ABEP (2003) Brazilian criterion of economic classification. http://www.abep.org. Accessed 04 October 2006

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2010) Committee opinion no. 453: screening for depression during and after pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 115:394–395

Castro IR, Engstrom EM, Cardoso LO, Damião Jde J, Rito RV, Gomes MA (2009). Time trend in breast-feeding in the city of Rio de Janeiro, Southeastern Brazil: 1996–2006. Rev Saude Publica 43:1021–1029

Chaudron LH, Szilagyi PG, Kitzman HJ, Wadkins HIM, Conwell Y (2004) Detection of postpartum depressive symptoms by screening at well-child visits. Pediatrics 113:551–558

Cox J, Holden J (2003) Perinatal mental health: a guide to the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). Royal College of Psychiatrists, Gaskell

Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R (1987) Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry 150:782–786

Elliott S (2000) Report on the satra bruk workshop on classification of postnatal mental disorders on November 7–10, 1999, convened by Birgitta Wickberg, Philip Hwang and John Cox with the support of Allmanna Barhuset represented by Marina Gronros. Arch Womens Ment Health 3:27–33

Ewing JA (1984) Detecting alcoholism: the CAGE questionnaire. JAMA 252:1905–1907

Faisal-Cury A, Tedesco JJA, Kahhale S, Menezes PR, Zugaib M (2004) Postpartum depression: in relation to life events and patterns of coping. Arch Womens Ment Health 7:123–131

Gibson J, McKenzie-McHarg K, Shakespeare J, Price J, Gray R (2009) A systematic review of studies validating the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in antepartum and postpartum women. Acta Psychiatr Scand 119:350–364

Gjerdingen DK, Yawn BP (2007) Postpartum depression screening: importance, methods, barriers, and recommendations for practice. J Am Board Fam Med 20:280–288

Grace SL, Evindar A, Stewart DE (2003) The effect of postpartum depression on child cognitive development and behavior: a review and critical analysis of the literature. Arch Womens Ment Health 6:263–274

Halbreich U, Karkun S (2006) Cross-cultural and social diversity of prevalence of postpartum depression and depressive symptoms. J Affect Disord 91:97–111

Hammen C, Brennan PA (2003) Severity, chronicity, and timing of maternal depression and risk for adolescent offspring diagnoses in a community sample. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60:253–258

Hasselmann MH, Werneck GL, Silva CVC (2008) Symptoms of postpartum depression and early interruption of exclusive breastfeeding in the first 2 months of life. Cad Saúde Pública 24:S341–S352

Hastie T, Tibshirani R (1990) Generalized additive models. Chapman and Hall, London

Hiscock H, Wake M (2001) Infant sleep problems and postnatal depression: a community-based study. Pediatrics 107:1317–1322

Jadresic E, Nguyen DN, Halbreich U (2007) What does Chilean research tell us about postpartum depression (PPD)? J Affect Disord 102:237–243

Kendell RE, Chalmers JC, Platz C (1987) Epidemiology of puerperal psychoses. Br J Psychiatry 150:662–673 [erratum appears in Br J Psychiatry, 1987 Jul; 1151:1135]

Masur J, Monteiro MG (1983) Validation of the “CAGE” alcoholism screening test in a Brazilian psychiatric inpatient hospital setting. Braz J Med Biol Res 16:215–218

Matthey S (2010) Are we overpathologising motherhood? J Affect Disord 120:263–266

Mayfield D, McLeod G, Hall P (1974) The CAGE questionnaire: validation of a new alcoholism screening instrument. Am J Psychiatry 131:1121–1123

Moraes IGS, Pinheiro RT, Silva RAS, Horta BL, Sousa PLR, Faria AD (2006) Prevalence of postpartum depression and associated factors. Rev Saúde Pública 40:65–70

Murray L, Carothers AD (1990) The validation of the Edinburgh Post-natal Depression Scale on a community sample. Br J Psychiatry 157:288–290

O'Hara MW, Swain AM (1996) Rates and risk of postpartum depression—a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry 8:37–54

Rahman A, Bunn J, Lovel H, Creed F (2007) Maternal depression increases infant risk of diarrhoeal illness: a cohort study. Arch Dis Child 92:24–28

Robertson E, Grace S, Wallington T, Stewart DE (2004) Antenatal risk factors for postpartum depression: a synthesis of recent literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 26:289–295

Ruschi GEC, Sun SY, Mattar R, Chambô Filho A, Zandonade E, Lima VJ (2007) Postpartum depression epidemiology in a Brazilian sample. Rev Psiquiatr Rio Gd Sul 29:274–280

Santos MFS, Martins FC, Pasquali L (1999) Post-natal depression self-rating scales: Brazilian study. Rev Psiq Clin 26:32–40

Smart RG, Arif A, Hughes P, Medina Mora ME, Navaratnam V, Varma VK, Wadud KA (1981) Drugs use among non-student youth. WHO offset publication, no. 60. Geneva, World Health Organization

StataCorp (2007) Stata statistical software, release 10. Stata Corporation, College Station

WHO, UNFPA (2009) Mental health aspects of women's reproductive health. A global review of the literature. WHO Press, Geneva

Wisner KL, Moses-Kolko EL, Sit DK (2010) Postpartum depression: a disorder in search of a definition. Arch Womens Ment Health 13:37–40

Acknowledgments

The study was sponsored by the Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ), process no. E-26/110.365/2007-APQ1. MER was partially supported by the Brazilian National Research Council (CNPQ), process no. 306909/2006-5. CLM was partially supported by the Brazilian National Research Council (CNPQ), process no. 302851/2008-9. The authors are very thankful to the health professionals of the health units where the research took place and also to the fieldwork team.

Disclosure of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lobato, G., Moraes, C.L., Dias, A.S. et al. Postpartum depression according to time frames and sub-groups: a survey in primary health care settings in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Arch Womens Ment Health 14, 187–193 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-011-0206-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-011-0206-6