Abstract

Perineural spread has been described in multiple neoplasms of neural and non-neural origin. The peripheral nervous system may represent a highway by which tumors can spread throughout the body. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) is a neoplasm arising from peripheral nerves with high rates of local recurrence and distant metastases, leading to a poor 5-year overall survival. In many cases, the optimal treatment involves wide en bloc excision with negative margins as well as chemotherapy and radiation. Even in cases of negative surgical margins, recurrence rates are high, suggesting possible skip lesions or very distant infiltration along the involved nerve. We report a case of high-grade MPNST of the sciatic nerve with post-mortem dissection and histopathologic characterization of perineural spread of microscopic disease to sites significantly proximal and distal to areas with evidence of gross disease, which may help to explain the high rates of local and distal recurrence in MPNST.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

MPNST is an aggressive neoplasm of the peripheral nervous system, seen sporadically as well as in patients with NF-1 [2, 6]. Exposure to radiation may also be a causative mechanism, with up to 10% of MPNST patients reporting a prior history of exposure to radiation [6]. Treatment often involves complete surgical resection with negative margins, with adjuvant (or neoadjuvant) radiation and chemotherapy [10]. Despite aggressive treatment options, local recurrence (40–65%) and distant metastases (30–60%) are common [1, 8, 16]. Metastases often present in the lungs (nearly 65%); however, multi-system involvement is common, and even brain metastases have been reported [15]. Five year overall survival remains poor (20–50%) in cases of high-grade MPNST [7, 12]. As expected, positive margins on surgical pathology carry a 1.8-fold increased risk of mortality, highlighting the importance of attempting an en bloc resection with negative margins. We report a case of high-grade MPNST of the sciatic nerve with post-mortem dissection and histopathologic characterization of perineural spread of microscopic disease to sites significantly proximal and distal to areas with evidence of gross disease, which may help to explain the high rates of local and distal recurrence in MPNST.

Case presentation and course

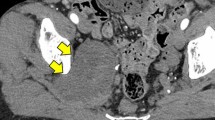

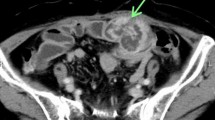

A 60-year-old woman with neurofibromatosis type I presented with pelvic pain, right leg numbness, and a right foot drop. Initial workup demonstrated a pelvic mass concerning for ovarian cancer (Fig. 1a). A laparascopic left oophorectomy was performed at an outside institution, during which, a large pelvic mass was identified. Intraoperative biopsies demonstrated only necrotic tissue and were otherwise non-diagnostic. Further imaging demonstrated a 15 × 8-cm mass extending through the right sciatic notch into the posterior thigh with hypermetabolic regions on PET (Fig. 1b). CT-guided biopsy demonstrated high-grade malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor. There was no evidence of systemic disease at diagnosis, but her disease burden was not amenable to surgical resection. She died approximately 8 months after initial diagnosis, presumably from disease progression, and donated her body for research into the progression of MPNST. Post-mortem imaging demonstrated a massive intrapelvic mass with sacral erosion and intradural extension (Fig. 1c). A post-mortem dissection was performed to evaluate extent of disease progression both grossly and microscopically via histopathologic evaluation along the sciatic nerve. The cause of death was not determined during the post-mortem dissection.

Post-mortem dissection

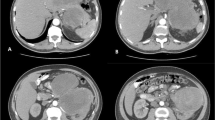

The sciatic nerve was resected from the conus medullaris through the distal common peroneal nerve at the fibular neck and distal tibial nerve at the mid-calf (Fig. 2). Histopathological specimens were stained to identify areas of tumor involvement along the sciatic nerve. The pathological pattern suggested a sciatic point of origin, but tumor was found to be extending intradurally along the cauda equina to the gray matter of the conus medullaris proximally, and along the common peroneal nerve distally, with no evidence of disease in the distal tibial nerve in the mid-calf. Within the sciatic nerve of the thigh (both proximal and distal), the peroneal division appears involved and expanded, with relative sparing of the tibial division. This pattern may suggest perineural extension along involved fascicles which provide a pathway for tumor extension. Proximal invasion allows for rapid expansion to other nerves via the lumbosacral plexus, as well as central nervous system involvement as the tumor crosses the dura and reaches the conus via nerve roots of the cauda equina. Evidence of microscopic disease was identified well beyond identifiable tumor on gross pathology, and skip lesions were present, with tumor discovered distal to regions without evidence of disease.

Cadaveric dissection and histopathologic analysis of the sciatic nerve from intradural conus medullaris to distal tibial nerve in the mid-calf (ankle region not shown). Microscopic evidence of tumor was found distant to gross disease (+), extending proximally along the cauda equina after crossing and involving the dura, to invade the gray matter of the conus medullaris as well as distally where involvement was noted in the common peroneal nerve at the fibular neck, but not in the distal tibial nerve at the ankle (−). The peroneal division of the sciatic nerve in the thigh (proximal and distal sciatic nerve) was involved with relative sparing of the tibial division, suggesting preferential invasion along individual nerve fascicles rather than between nerve fascicles of the involved nerve

Discussion

We report a case of sciatic MPNST with progression along a perineural highway both proximally to the central nervous system as well as distally along the involved nerve. The patient’s donation after her death allowed the complete histopathological documentation of this mechanism of infiltration in MPNST. This rapid invasion of microscopic disease along nervous tissue mimics patterns seen in glial neoplasms of the brain and may help to explain the high rates of local and distant recurrence despite aggressive resection strategies utilizing en bloc resection with negative margins in cases of MPNST. This case illustrates the extensive potential and nature of perineural spread along a neural highway, increasingly understood as a mechanism by which some tumors of both neural and non-neural origin spread throughout the body [3,4,5, 9, 13, 14].

Identifying cases of MPNST with extensive perineural spread pre-operatively may be difficult with current imaging technologies, as involved tissue can appear normal upon gross examination. Correlation studies utilizing high-resolution MR neurography or potentially ultrasound may elicit subtle changes suggestive of perineural spread, but these findings would have to be corroborated with histopathological evidence either from surgical resection or post-mortem dissection. It has been suggested that MR neurography has a high sensitivity (> 95%) for detecting neuronal pathology, including perineural spread [11]. Specific MR techniques, including T1 non-contrast sequences to look for nerve inhomogeneity, T2-weighted sequences looking for denervation of musculature, and gadolinium-enhanced sequences may help to identify regions of involved nerve proximal and distal to the index lesion. The radiologist should be made aware of the potential for perineural spread, thus allowing them to target sequences to identify the presence or absence of radiographic characteristics consistent with perineural spread [11]. Intraoperatively, the surgical team will need to rely on a trained neuropathologist to identify evidence of perineural spread within the margins that may appear grossly normal. If perineural spread is identified in margin tissue during surgery, it should be considered that microscopic disease may have already crossed into the CNS and far distally from the operative site. Even with negative margins, microscopic skip lesions may be present beyond the extent of resection.

Conclusion

This case of sciatic MPNST highlights the diffuse, infiltrative nature of disease progression along perineural pathways, which may help to explain high rates of local and distant recurrence of disease after aggressive, en bloc resection with negative margins.

References

Anghileri M, Miceli R, Fiore M, Mariani L, Ferrari A, Mussi C, Lozza L, Collini P, Olmi P, Casali PG, Pilotti S, Gronchi A (2006) Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors: prognostic factors and survival in a series of patients treated at a single institution. Cancer 107:1065–1074. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.22098

Bradtmoller M, Hartmann C, Zietsch J, Jaschke S, Mautner VF, Kurtz A, Park SJ, Baier M, Harder A, Reuss D, von Deimling A, Heppner FL, Holtkamp N (2012) Impaired Pten expression in human malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours. PLoS One 7:e47595. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0047595

Capek S, Amrami KK, Howe BM, Spinner RJ (2015) Perineural tumor spread to the muscle: an alternative for muscle metastasis? Clin Anat 28:560–562. https://doi.org/10.1002/ca.22485

Capek S, Howe BM, Amrami KK, Spinner RJ (2015) Perineural spread of pelvic malignancies to the lumbosacral plexus and beyond: clinical and imaging patterns. Neurosurg Focus 39:E14. https://doi.org/10.3171/2015.7.FOCUS15209

Capek S, Krauss WE, Amrami KK, Parisi JE, Spinner RJ (2016) Perineural spread of renal cell carcinoma: a case illustration with a proposed anatomic mechanism and a review of the literature. World Neurosurg 89(728):e711–e727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2016.01.060

Ducatman BS, Scheithauer BW, Piepgras DG, Reiman HM, Ilstrup DM (1986) Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. A clinicopathologic study of 120 cases. Cancer 57:2006–2021

Eilber FC, Brennan MF, Eilber FR, Dry SM, Singer S, Kattan MW (2004) Validation of the postoperative nomogram for 12-year sarcoma-specific mortality. Cancer 101:2270–2275. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.20570

Goertz O, Langer S, Uthoff D, Ring A, Stricker I, Tannapfel A, Steinau HU (2014) Diagnosis, treatment and survival of 65 patients with malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Anticancer Res 34:777–783

Jacobs JJ, Capek S, Spinner RJ, Swanson KR (2018) Mathematical model of perineural tumor spread: a pilot study. Acta Neurochir 160:655–661. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-017-3423-6

James AW, Shurell E, Singh A, Dry SM, Eilber FC (2016) Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor. Surg Oncol Clin N Am 25:789–802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soc.2016.05.009

Kirsch CFE, Schmalfuss IM (2018) Practical tips for MR imaging of perineural tumor spread. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 26:85–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mric.2017.08.006

Lin CT, Huang TW, Nieh S, Lee SC (2009) Treatment of a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor. Onkologie 32:503–505. https://doi.org/10.1159/000226591

Marek T, Howe BM, Amrami KK, Spinner RJ (2018) Perineural spread of nonmelanoma skin Cancer to the brachial plexus: identifying anatomic pathway(s). World Neurosurg doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2018.03.092

Marek T, Laughlin RS, Howe BM, Spinner RJ (2018) Perineural spread of melanoma to the brachial plexus: identifying the anatomic pathway(s). World Neurosurg 111:e921–e926. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2018.01.031

Puffer RC, Graffeo CS, Mallory GW, Jentoft ME, Spinner RJ (2016) Brain metastasis from malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. World Neurosurg 92:580 e581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2016.06.069

Wong WW, Hirose T, Scheithauer BW, Schild SE, Gunderson LL (1998) Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor: analysis of treatment outcome. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 42:351–360

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Patient consent

The patient is deceased, but prior to her death consented to the donation of her body for research purposes and also for publication of any results associated with her post-mortem evaluation. Therefore, she has consented to the submission of this case report to this journal.

Additional information

Comments

A very interesting paper that provides an explanation for why malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors can be so challenging to treat as a result of extensive perineurial speed both proximally and distally. It will be interesting to chart the progress of high-resolution MRN and even ultrasound techniques to visualize nerve imaging abnormalities that might suggest or indicate such spread pre-operatively or pre-post-mortem.

Michel Kliot

CA, USA

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Brain Tumors

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Puffer, R.C., Marek, T., Stone, J.J. et al. Extensive perineural spread of an intrapelvic sciatic malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor: a case report. Acta Neurochir 160, 1833–1836 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-018-3619-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-018-3619-4