Abstract

Introduction

Glomus jugulare tumours represent a great therapeutic challenge. Previous papers have documented good results from Gamma Knife surgery (GKS) with these tumours. However, the relationship between clinical improvement and tumour shrinkage has never been assessed.

Materials and methods

There were 14 patients, 9 women and 5 men. The mean follow-up period was 28 months (range 6 to 60 months). All the tumours except one were Fisch type D and the mean volume was 14.2 cm3 (range 3.7–28.4 cm3). The mean prescription dose was 13.6 Gy (range 12–16 Gy).

Results

None of the tumours have continued to grow. Eight are smaller and 6 unchanged in volume. Two patients with bruit have had no improvement in their symptoms. Among the other 12 patients, 5 have had symptomatic improvement of dysphagia, 4 in dysphonia, 3 in facial numbness, 3 in ataxia and 2 in tinnitus. Individual patients have experienced improvement in vomiting, vertigo, tongue fasciculation, hearing, headache, facial palsy and accessory paresis. One patient developed a transient facial palsy. Symptomatic improvement commonly began before any reduction in tumour volume could be detected. The mean time to clinical improvement was 6.5 months whereas the mean time to shrinkage was 13.5 months.

Conclusions

Gamma Knife treatment of glomus jugulare tumours is associated with a high incidence of clinical improvement with few complications, using the dosimetry recorded here. Clinical improvement would seem to be a more sensitive early indicator of therapeutic success than radiological volume reduction. Further follow-up will be needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Glomus tumours are rare [5, 6, 10, 15], slow-growing tumours. Surgical resection can be difficult and associated with significant morbidity as a result of their location and nature. Thus, non-operative treatment methods are an attractive alternative. Radiosurgical treatment has been reported on numerous occasions [1–5, 9–12, 14, 16, 17, 19] and the effectiveness of Gamma Knife surgery in the first few years after treatment has been well documented [1–5, 9, 11, 14, 17, 19]. Clinical improvement in the presence of unchanged tumour volume has been recorded before [2, 3, 4, 9]. To date, this phenomenon has been recorded but never assessed. The purpose of this report is to record a series of patients and comment on the relationship between the clinical and radiological responses after treatment and the relationship between these two responses.

Materials and methods

There were 14 patients, 9 women and 5 men; selected from a total of 27 referred patients. Grounds for refusing a patient were as follows: in 8 patients the tumour was too large; in 2 patients the tumour was largely extracranial and inaccessible to the Gamma Knife; in 2 patients investigations were requested, but the patients never returned; and in 1 case metal clips placed at the time of surgery produced artefacts that made geometrically accurate imaging impossible. The mean follow-up period was 28 months (range 6–60 months). All the tumours except one were Fisch Type D and the mean volume was 14.2 cm3 (range 3.7–28.4 cm3). The mean prescription dose was 13.6 Gy (range 12–16 Gy).

In 3 patients previous surgery had confirmed the diagnosis. In the remainder the diagnosis was based on MR findings and a typical angiogram supplied mainly by the ascending pharyngeal artery.

Results

None of the tumours has continued to grow. Eight are smaller and 6 unchanged in volume. Two patients with bruit have had no improvement in their symptoms. Among the other 12 patients, 5 have had improvement in their symptoms of dysphagia, 4 of dysphonia, 3 of facial numbness, 3 of ataxia and 2 of tinnitus. Individual patients have experienced improvement in vomiting, vertigo, tongue fasciculation, hearing, headache, facial palsy and accessory paresis. One patient developed a transient facial palsy. Symptomatic improvement commonly began before any reduction in tumour volume could be detected. The mean time to clinical improvement was 6.5 months, whereas the mean time to shrinkage was 13.5 months.

Illustrative case

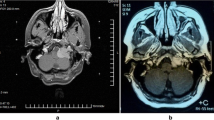

This is an unusual case in view of the age of the patient who was only 16. He presented in April 2003 with epistaxis. He was packed and cauterisation was performed. After this he developed continuous nodding of the head. He also had more or less continuous blinking. In May 2003 he had some sort of attack with unconsciousness but without incontinence. He also complained of right-sided retromastoid pain. On examination there was slight rotation and tilting of the chin to the left. There was a minimal right hypoglossal weakness with wasting and deviation but no fasciculation. There was a clearly visible cherry red tumour behind the eardrum on the right side. He was deaf in that ear. There was no vagus deficit. He was treated with 12 Gy to the 35% isodose with 91% cover and a conformity index of 1.22. MRI showed the tumour and an angiogram showed that it was vascular and mainly supplied by the ascending pharyngeal artery with a contribution from the middle meningeal artery.

The patient was treated on 9 July 2003 and the tumour appearance is shown in Fig. 1. The extension into the neck is the reason for a low prescription isodose because otherwise the tumour would be outside the reach of the Gamma Knife.

At the 6-month follow-up no change was visible on the MR images. Moreover, the extent of the tumour in the middle ear seemed unchanged. However, there was a clear clinical improvement. He reported that the blinking had ceased. His tongue was now normal and as Fig. 2 shows, the tilting and rotation of the head had resolved.

Discussion

This series can be criticised on two grounds. In the majority of patients there was no histological diagnosis and the patients were selected. The absence of biopsy is unavoidable in many cases since these vascular tumours do not lend themselves to stereotactic procedures and open surgery, even for biopsy, could be a major undertaking and it was considered inappropriate to expose patients to such a procedure that was not aimed at therapy. The case selection is also unavoidable since at presentation not all glomus tumours are suitable for radiosurgery, mostly because of their size. Thus, it is emphasised that radiosurgery cannot be the only primary treatment for these tumours, but that in cases in which the tumour is of a suitable volume it represents an attractive alternative to surgery.

Glomus tumours are rare [5, 6, 10, 15, 20] and mostly benign [5, 6, 12, 17]. They produce lower cranial nerve symptoms, which have a marked effect on quality of life [5, 10, 12, 14, 17, 20]. The tumour entity was first described by Valentin in 1840 [18]. However, Guild [8] proposed the term glomus tumour at a meeting of anatomists in Chicago in 1941. The tumours are thought to arise from either the glossopharyngeal or the vagus nerve and the cells contain chromaffin. The classical treatment has been surgery with or without radiotherapy [5–7, 10, 12–14, 17, 19]. Because of the location, local anatomy and vascularity of these tumours, post-operative complications in the form of new cranial neuropathy are not uncommon [6, 7, 15, 20]. In addition, total removal is not always possible [6, 7, 15, 20]. Moreover, these complications are compounded by the more usual complications of surgery such as haematomas CSF leaks and infections [6, 7, 15, 20]. Radiotherapy has been difficult to assess because of the slowness of the response of the tumours. However, there is evidence that low-dose treatment is associated with recurrence [7, 13] and that high-dose treatment may be associated with radiation-induced complications [5, 7, 10, 19].

In view of the various difficulties associated with conventional treatments, it was natural to consider radiosurgery as a treatment modality and there are now a number of series recording good short-term results [1–5, 9–14, 16, 17, 19]. The first paper recording the results of treating glomus tumours with radiosurgery was published in 1997 [3]. Because of the recent introduction of this technique for glomus tumour management, it is unavoidable that late follow-up results will only begin to appear in the future. Nonetheless, the early results make this treatment modality attractive, providing it is borne in mind that in common with the experience recorded in this paper, radiosurgery will always be limited to a selected group of patients and will never be appropriate for all patients.

Only the passage of time will permit the registration of late follow-up. However, the tumour shrinkage recorded in most series of Gamma Knife treatment [1, 2, 4, 5, 11, 14, 16, 17, 19] is in contrast to the lack of such shrinkage following radiotherapy [12]. This suggests that radiosurgery could be a more useful treatment for these tumours.

The current series is consistent with earlier reports in that 8 tumours shrank while 6 remained unchanged [2, 4, 5, 9]. On the other hand, 10 patients experienced clinical improvement of a wide variety of symptoms. In addition, the clinical improvement antedated radiological shrinkage in all the patients whose tumours showed shrinkage during the observation period of this study. This mismatch between clinical improvement and volume reduction has been reported previously in a number of papers [2, 3, 4, 9], but has never been analysed or made the subject of comment. If clinical improvement occurs before recordable changes in volume, this could come to be considered a reliable measure of early therapeutic success. None of the patients in this series with clinical improvement has suffered a subsequent deterioration. If this is confirmed in other studies, it will be a useful assessment parameter in the management of these tumours.

The mechanism of clinical improvement in the absence of radiological improvement is not known and may be difficult to determine. Among the more likely explanations are inaccurate volume determination, changes in blood supply or changes in chemicals produced by the tumour.

This series confirms that Gamma Knife surgery seems to be a useful treatment technique for selected glomus jugulare tumours. It also suggests that early clinical improvement may be a useful measure of long-term therapeutic success, but longer follow-up will be needed to confirm this notion. It could be advantageous for further studies to include follow-up angiograms, to check if changes in vascularity can be seen in patients with clinical improvement but no change in volume.

Conclusion

Clinical improvement following Gamma Knife surgery for glomus jugulare tumours may, on further observation, prove to be a reliable index of early therapeutic success, preceding shrinkage.

References

Bari ME, Kemeny AA, Forster DM, Radatz MW (2003) Radiosurgery for the control of glomus jugulare tumours. J Pak Med Assoc 53(4):147–151

Eustacchio S, Trummer M, Unger F, Schrottner O, Sutter B, Pendl G (2002) The role of Gamma Knife radiosurgery in the management of glomus jugular tumours. Acta Neurochir Suppl 84:91–97

Foote RL, Coffey RJ, Gorman DA, Earle JD, Schomberg PJ, Kline RW et al (1997) Stereotactic radiosurgery for glomus jugulare tumours: a preliminary report. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 38(3):491–495

Foote RL, Pollock BE, Gorman DA, Schomberg PJ, Stafford SL, Link MJ et al (2002) Glomus jugulare tumour: tumour control and complications after stereotactic radiosurgery. Head Neck 24(4):332–338

Gerosa M, Visca A, Rizzo P, Foroni R, Nicolato A, Bricolo A (2006) Glomus jugulare tumours: the option of gamma knife radiosurgery. Neurosurgery 59(3):561–569

Gjuric M, Seidinger L, Wigand ME (1996) Long-term results of surgery for temporal bone paraganglioma. Skull Base Surg 6(3):147–152

Gottfried OB, Couldwell WT (2004) Comparison of radiosurgery and conventional surgery for the treatment of glomus jugulare tumours. Neurosurg Focus 17(2):22–30

Guild SR (1993) The glomus jugulare, a nonchromaffin paraganglionoma in man. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 62:1045–1071

Leber KA, Eustacchio S, Pendl G (1999) Radiosurgery of glomus tumours: midterm results. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg 72[Suppl 1]:53–59

Lim M, Gibbs IC, Adler JR, Chang SD (2004) Efficacy and safety of stereotactic radiosurgery for glomus jugulare tumours. Neurosurg Focus 17(2):68–72

Liscak R, Vladyka V, Wowra B, Kemeny A, Forster D, Burzaco JA et al (1999) Gamma Knife radiosurgery of the glomus jugulare tumour—early multicentre experience. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 141(11):1141–1146

Maarouf M, Voges J, Landwehr P, Bramer R, Treuer H, Kocher M et al (2003) Stereotactic linear accelerator-based radiosurgery for the treatment of patients with glomus jugulare tumours. Cancer 97(4):1093–1098

Michael LM, Robertson JH (2004) Glomus jugulare tumours: historical overview of the management of this disease. Neurosurg Focus 17(2):1–5

Pollock BE (2004) Stereotactic radiosurgery in patients with glomus jugulare tumours. Neurosurg Focus 17(2):63–67

Ramina R, Maniglia JJ, Fernandes YB, Paschoal JR, Pfeilsticker LN, Neto MC (2004) Jugular foramen tumours: diagnosis and treatment. Neurosurg Focus 17(2):31–40

Saringer W, Khayal H, Ertl A, Schoeggl A, Kitz K (2001) Efficiency of gamma knife radiosurgery in the treatment of glomus jugulare tumours. Minim Invasive Neurosurg 44(3):141–146

Sheehan J, Kondziolka D, Flickinger J, Lunsford LD (2005) Gamma knife surgery for glomus jugulare tumours: an intermediate report on efficacy and safety. J Neurosurg 102 [Suppl]:241–246

Valentin G (1840) Über eine gangliose Anschwellung in der Jacobsonchen Anastomose des Menschen. Arch Anat Physiolog Lpz 16:287–290

Varma A, Nathoo N, Neyman G, Suh JH, Ros SJ, Par KJ (2006) Gamma knife radiosurgery for glomus jugulare tumours: volumetric analysis in 17 patients. Neurosurgery 59(5):1030–1036

Watkins LD, Mendoza N, Cheesman AD, Symon L (1994) Glomus jugulare tumours: a review of 61 cases. Acta Neurochir 130:66–70

Acknowledgement

The author thanks Dr. Paal Henning Pedersen for reviewing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ganz, J., Abdelkarim, K. Glomus jugulare tumours: certain clinical and radiological aspects observed following Gamma Knife radiosurgery. Acta Neurochir 151, 423–426 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-009-0268-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-009-0268-7