Abstract

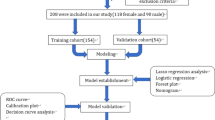

Tools designed to predict patient satisfaction following total knee arthroplasty (TKA) have the potential to guide patient selection. Our study aimed to validate a model that predicts patient satisfaction following TKA. Phone surveys were administered to 203 patients who underwent TKA between 2009 and 2016 at the University of Illinois. We utilized health records to document age, gender, body mass index (BMI), and comorbidities. First, we compared the descriptive variables between the satisfied and dissatisfied groups. We then performed multivariate linear regression and multiple logistic regression to assess the predictive value of the questions in the Van Onsem et al. model. The true satisfaction rate in our study was 65%. The Van Onsem et al. model predicted a satisfaction rate of 70%. The scatter plot of predicted satisfaction score versus observed satisfaction score showed poor agreement between actual satisfaction and predicted satisfaction. Comparing satisfied and dissatisfied groups, there was a significant difference with respect to pain prior to surgery and BMI. The validity of the Van Onsem et al. prediction tool was not supported. While the predicted satisfaction rate was near the measured satisfaction rate, the model misidentified which patients were likely to be satisfied. Preoperative variables including pain, anxiety/depression, and a patient’s ability to control pain symptoms showed potential for inclusion in future prediction models.

Level of evidence

Level III, developing a decision model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Background

The number of total knee replacements performed annually in the USA is expected to grow by 673% to 3.48 million procedures by 2030 [1]. It is also well documented that only 68–93% of patients report satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) [2,3,4,5]. Thus, there is an increasing need for an easy to use, robust prediction model to aid patient selection of TKA.

There are several patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) questionnaires available, such as the New Knee Society Score (KSS) [6], the Western Ontario and McMasters Universities Arthritis Index [7], the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) [8], and the Oxford Knee Score (OKS) [9] that are easy to use and well validated. However, they are not prediction tools. Given the current satisfaction rates reported in the literature (68–93%), a prediction tool is necessary to improve satisfaction scores.

Providing patients their probability of dissatisfaction following TKA prior to intervention is an important preoperative assessment. It has benefits for patients, clinicians, and the health-care system. For example, patients with modifiable risk factors may undergo treatment prior to TKA to reduce their risk of dissatisfaction. Patients who know that they are at a high risk of dissatisfaction may readjust their expectations, ultimately improving their satisfaction [10]. Finally, some patients may elect not to undergo surgery and pursue different treatment options. Knowing the risk of patient dissatisfaction prior to surgery will enhance clinician and patient shared decision making and will improve patient satisfaction rates. However, a prediction tool is necessary to achieve these results.

Few studies have identified predictors of patient satisfaction following TKA, and the current evidence fails to conclusively support any preoperative predictors of outcome [2, 11,12,13]. The study performed by Van Onsem et al. is the first to our knowledge to intensely investigate the correlation between preoperative patient-specific variables and postoperative satisfaction using PROM questionnaires and create a prediction model [14].

The prediction model developed by Van Onsem et al. [14] includes only 10 predictive variables making it a simple, easy to use model. However, generalizability to diverse clinical sites is an import factor in generating such prognostic models. Thus, the predictive tool created by Van Onsem et al. must be validated with a diverse, independent group of subjects before it can be recommended for widespread use [15].

Study question

Our goal was to validate the prediction model designed by Van Onsem et al. on an independent data set.

Methods

Study design and setting

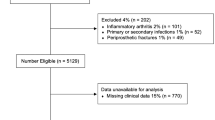

Prior to initiation of this study, institutional review board approval was obtained from the University of Illinois at Chicago College of Medicine. We retrospectively identified and contacted 203 patients that underwent primary TKA for arthritis at the University of Illinois Hospital between 2009 and 2016.

Van Onsem et al. administered 5 questionnaires totaling 107 questions preoperatively and postoperatively to 113 patients [14]. Ultimately, 10 questions were retained in the prediction tool (Table 1). Thus, we gathered data on these 10 questions and patient satisfaction.

Our survey included 8 of the 10 questions that Van Onsem et al. included in their prognostic model [14], 5 questions from the KSS [6] satisfaction subscale, and 3 questions regarding education and socioeconomic status (SES). The survey consisted of 16 questions in total.

To reduce the length of the phone survey, we did not ask subjects their age or gender, the two remaining questions in the Van Onsem et al. prediction model. Instead, we utilized electronic health records to gather data on age at time of surgery and gender, as well as body mass index (BMI), insurance provider, and comorbidities.

Van Onsem et al. measured satisfaction with the KSS. The KSS is divided into 4 subscales which are rated separately. The satisfaction subscale consists of 5 items. Each item is scored from 0 to 5 points for a maximum score of 40 points. Van Onsem et al. used this score as a continuous variable and as a dichotomized variable where a score of ≥ 20 qualified as satisfied and a score < 20 dissatisfied [14]. We adopted this same criterion. Finally, if a subject had multiple TKAs, we asked them to report on the most recent surgery.

Statistical analysis, study size

A statistician in the Department of Mathematics, Statistics, and Computer Science at the University of Illinois Chicago guided the statistical analysis; 203 patients agreed to participate and completed the entire survey. To ensure the respondents represented the population of patients undergoing TKA between 2009 and 2016, we compared participants and nonparticipants.

To validate the prognostic model, we utilized the coefficients reported by Van Onsem et al., which are displayed in Table 1. With these coefficients, a scatter plot of predicted satisfaction score versus observed satisfaction score was generated (Fig. 1). Comparisons between the satisfied and dissatisfied groups were made using a Student t test (Table 2). We then performed a multivariate linear regression and a multiple logistic regression analysis with the questionnaire results, age at time of surgery, gender, BMI, payment method, education, and comorbidities as the independent variable and the satisfaction subscore of the KSS as the dependent variable (Tables 3, 4). This allowed us to compare the predictive qualities of our data set for the 10 questions selected by Van Onsem et al. [14].

Results

A total of 203 patients completed the 16 question phone survey. The mean age at time of surgery was 59.7 (SD 8.7, range 40–90) and the average BMI was 35.7 (SD 7.2, range 14–59). 73% of respondents were female and 52% were right knee surgeries. 51% of respondents attended college or technical school for one or more years while 49% of respondents never attended college or technical school. Comparisons between the satisfied and dissatisfied groups are displayed in Table 2.

Using a KSS satisfaction subscore of ≥ 20 as satisfied and score < 20 as dissatisfied, the calculated satisfaction rate was 65%. When applying the coefficients reported by Van Onsem et al., the predicted satisfaction rate was found to be 70% and the scatter plot of predicted satisfaction score versus observed satisfaction score is displayed in Fig. 1.

Multiple linear regression analysis and a multiple logistic regression analysis were performed to understand the predictive value of the 10 items identified by Van Onsem et al. In addition to the 10 items included in the Van Onsem et al. questionnaire, we also evaluated the predictive value of BMI, comorbidities, payment method, income, and education. The predictors BMI (p < 0.01), pain prior to surgery (p < 0.01), and anxiety and depression prior to surgery (p < 0.01) were statistically significant in the multiple linear regression analysis. The model R2 value was 0.27 (adjusted R2 = 0.15). BMI (p < 0.01), pain prior to surgery (p < 0.01), anxiety and depression prior to surgery (p < 0.05), hypertension (p < 0.05), and pain mindfulness (p < 0.05) were statistically significant predictors of satisfaction in the multiple logistic regression analysis.

Discussion

Background and rationale

While many scoring systems such as the KSS [6], the Western Ontario and McMasters Universities Arthritis Index [7], the KOOS [8], and the OKS [9] are well validated and easy to use, they only assess knee replacement outcome. They are not prediction tools. Moreover, we believe the current satisfaction rates reported in the literature (68–93%) are low and can be improved. A prediction tool is necessary to improve satisfaction scores. The study performed by Van Onsem et al. is the first attempt to our knowledge to consolidate these PROMs into a simple, robust questionnaire that can be scored and substituted into a model to predict patient satisfaction following TKA before surgical intervention. Our study aimed to externally validate the Van Onsem et al. model on an independent data set.

The results of our study failed to support the external validity of the Van Onsem et al. model. While their model was accurate in predicting the satisfaction score in our TKA population (true satisfaction 65%, predicted satisfaction 70%), the scatter plot of predicted satisfaction score versus observed satisfaction score (Fig. 1) illustrates a poor correlation between individuals predicted to be satisfied and those who were truly satisfied. The predictive model misidentified which patients were likely to be satisfied. Thus, the model developed by Van Onsem et al. has poor predictive value in our TKA population and we fail to conclude that it is a good predictor of patient satisfaction.

To better understand why the Van Onsem et al. model had poor predictive value in our TKA population, we made comparisons between the satisfied and dissatisfied groups, which revealed that the only variables with a significant difference were BMI and pain. Those with a greater BMI and less pain prior to surgery were more likely to be dissatisfied. Of these two variables, Van Onsem et al. only consider pain in their prediction model. Like our study, previous research has found that patients with a greater BMI are more likely to be dissatisfied following TKA [16]. Although Van Onsem et al. found no significant difference between satisfied and dissatisfied groups with respect to BMI, future models should consider including BMI as a predictive variable.

We also performed multivariate linear regression analysis and multiple logistic regression analysis. In the multivariate linear regression analysis, BMI and anxiety/depression were statistically significant variables in predicting satisfaction. Patients with a greater BMI, more pain, and increased anxiety and depression were more likely to be dissatisfied. This provides further evidence that questions 3 and 8 in the model designed by Van Onsem et al. have predictive value. However, the model R2 value was only 0.27 (adjusted R2 = 0.15) leading us to reject it as helpful in improving satisfaction rates. The multiple logistic regression analysis found two additional variables to be significant predictors of satisfaction: ability to control pain symptoms (Q9, Table 1) and a past medical history of hypertension. Given these results, we concluded that questions 3, 8, and 9 from Van Onsem et al. contain significant predictive value and are worth retaining. Moreover, BMI is a variable worth considering for addition to the model or for replacing other questions.

Previous research has found that females have increased odds of reporting dissatisfaction following TKA [17] while other studies report no relationship between gender and dissatisfaction [5]. Our study failed to conclude that gender is predictive of satisfaction following TKA. Thus, it may be worth considering the replacement of gender with a stronger predictive variable like BMI in the model developed by Van Onsem et al. [14].

Our study has several strengths. First, it contained 203 individuals, almost twice as many as Van Onsem et al. Second, the demographic of our patient population allowed us to validate the prediction model developed by Van Onsem et al. on a much different population. For example, the average age in our population was 59.7 versus 65.2 as reported by Van Onsem et al. and the mean BMI was 35.7 versus 29.3. Further, 63% of our patients identified as African–American, 17% Hispanic, 14% Caucasian, 4% “other,” and 2% Asian. 67% of subjects reported an annual household income of less than USD 25,000. Nearly half of our subjects (49%) never attended college or technical school. Thus, we believe the diversity of our patient cohort was ideal for validating the generalizability of the model developed by Van Onsem et al.

Limitations

A major limitation of our study is that patients completed the survey retrospectively. However, there was no correlation between patient satisfaction rate and when the patient underwent surgery, which allows us to conclude that recall bias did not influence our results.

Another limitation of our study is that we did not measure patient satisfaction at a constant postoperative interval. The Van Onsem et al. prediction model was designed to predict satisfaction 3 months post-surgery. The mean time at which satisfaction was measured in our study was approximately 3 years. At 3 years post-surgery, most patients are well beyond the recovery phase where as at 3 months they are still following a rehabilitation program and are likely to make further improvements. Therefore, if we measured patient satisfaction at 3 months post-surgery, it is possible that our satisfaction rate may have been lower and our validation different.

Finally, a large proportion of those eligible elected not to participate in our study raising concern that respondents do not represent the universe of patients eligible to participate. It is also unclear if those who declined to participate did so randomly or because of lower satisfaction, higher pain scores, decreased function, or something else since we do not have outcome measures for nonparticipants. However, there were no statistically significant differences with respect to age, gender, or BMI when we compared participants and nonparticipants. This leads us to believe that the respondents are representative of the patient population eligible to participate.

Conclusions

The prediction model developed by Van Onsem et al. was not supported in our external validation study. The importance of pain (Q3, Table 1), anxiety and depression (Q8, Table 1), and mindfulness of pain (Q9, Table 1) was supported; however, we failed to conclude that the remaining questions regarding gender, age, symptoms, and quality of life contain predictive value. Significant modification to the Van Onsem et al. model or development of an entirely new model is warranted to improve patient satisfaction rates following TKA.

References

Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M (2007) Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am 89(4):780–785

Baker PN, Rushton S, Jameson SS, Reed M, Gregg P, Deehan DJ (2013) Patient satisfaction with total knee replacement cannot be predicted from pre-operative variables alone: a cohort study from the National Joint Registry for England and Wales. Bone Joint J 95-B(10):1359

Bullens PHJ, van Loon CJM, de Waal Malefijt MC, Laan RF, Veth RP (2001) Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: a comparison between subjective and objective outcome assessments. J Arthroplast 16(6):740

Noble PC, Conditt MA, Cook KF, Mathis KB (2006) The John Insall Award: patient expectations affect satisfaction with total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 452(452):35

Scott CE, Howie CR, MacDonald D, Biant LC (2010) Predicting dissatisfaction following total knee replacement: a prospective study of 1217 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br 92(9):1253–1258

Noble PC, Scuderi GR, Brekke AC et al (2012) Development of a new knee society scoring system. Clin Orthop Relat Res 470(1):20

Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW (1988) Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol 15(12):1833

Roos EM, Roos HP, Lohmander LS, Ekdahl C, Beynnon BD (1998) Knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS)—development of a self-administered outcome measure. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 28(2):88

Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Murrary D, Carr A (1998) Questionnaire on the perceptions of patients about total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 80:63

Bourne RB, Chesworth BM, Davis AM, Mahomed NN, Charron KDJ (2010) Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: who is satisfied and who is not? Clin Orthop Relat Res 468(1):57–63

Blackburn J, Qureshi A, Amirfeyz R, Bannister G (2012) Does preoperative anxiety and depression predict satisfaction after total knee replacement? Knee 19(5):522

Lunge E, Desmeules F, Dionne CE, Belzile EL, Vendittoli PA (2014) Prediction of poor outcomes six months following total knee arthroplasty in patients awaiting surgery. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 15:299

Williams DP, O’Brien S, Doran E et al (2013) Early postoperative predictors of satisfaction following total knee arthroplasty. Knee 20(6):442

Van Onsem S, Van der Straeten C, Arnout N, Deprez P, Van Damme G, Victor J (2016) A new prediction model for patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplast 31(12):2660

Altman DG, Vergouwe Y, Royston P, Moons KG (2009) Prognosis and prognostic research: validating a prognostic model. BMJ 338:b605

Kim TK, Chang CB, Kang YG, Kim SJ, Seong SC (2009) Causes and predictors of patient’s dissatisfaction after uncomplicated total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplast 24(2):263–271

Nam D, Nunley RM, Barrack RL (2014) Patient dissatisfaction following total knee replacement: a growing concern? Bone Joint J 96-B(11 Supple A):96–100

Acknowledgements

We thank Olufunmilayo Adeniji and Angie Figueroa for their help administering surveys. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zabawa, L., Li, K. & Chmell, S. Patient dissatisfaction following total knee arthroplasty: external validation of a new prediction model. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 29, 861–867 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00590-019-02375-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00590-019-02375-w