Abstract

Background

Surgical approaches for multi-level cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM) include posterior cervical surgery via laminectomy and fusion (LF) or expansive laminoplasty (EL). The relative benefits and risks of either approach in terms of clinical outcomes and complications are not well established. A systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted to address this topic.

Methods

Electronic searches were performed using six databases from their inception to January 2016, identifying all relevant randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and non-RCTs comparing LF vs EL for multi-level cervical myelopathy. Data was extracted and analyzed according to predefined endpoints.

Results

From 10 included studies, there were 335 patients who underwent LF compared to 320 patients who underwent EL. There was no significant difference found postoperatively between LF and EL groups in terms of postoperative JOA (P = 0.39), VAS neck pain (P = 0.93), postoperative CCI (P = 0.32) and Nurich grade (P = 0.42). The total complication rate was higher for LF compared to EL (26.4 vs 15.4 %, RR 1.77, 95 % CI 1.10, 2.85, I 2 = 34 %, P = 0.02). Reoperation rate was found to be similar between LF and EL groups (P = 0.52). A significantly higher pooled rate of nerve palsies was found in the LF group compared to EL (9.9 vs 3.7 %, RR 2.76, P = 0.03). No significant difference was found in terms of operative time and intraoperative blood loss.

Conclusions

From the available low-quality evidence, LF and EL approaches for CSM demonstrates similar clinical improvement and loss of lordosis. However, a higher complication rate was found in LF group, including significantly higher nerve palsy complications. This requires further validation and investigation in larger sample-size prospective and randomized studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM) is an age-related disorder associated with degeneration of intervertebral discs and adjacent vertebral structures. It is the most common spinal cord disorder in elderly patients, resulting in progressive spinal canal narrowing and subsequent nerve root compression [1, 2]. Early surgical treatment can alter the natural history of CSM as well as improve prognosis in selected patients [3].

For single-level CSM, an anterior surgical approach is typically employed as it confers greater ability to address compressing lesions while minimizing trauma and muscle loss [3, 4]. The anterior approach has also been associated with superior ability to provide decompression over kyphotic segments. However, anterior cervical fusion for multi-level CSM represents a more complex procedure and may be associated with longer operative times as well as complications such as graft dislodgement, hoarseness, dysphagia and trigeminal nerve palsy [2].

With regard to posterior surgical approaches, laminectomy alone has been the historical treatment standard for CSM decompression [5]. More recently, laminectomy has been performed in conjunction with lateral mass fixation or fusion to reduce the incidence of post-operative segmental instability and kyphosis [6–8]. Laminoplasty represents an alternative posterior approach for CSM that may enable better preservation of cervical motion, adjacent structural integrity and natural lordosis [9]. However, some studies have reported less effective and less extensive cord decompression for laminoplasty compared to laminectomy and fusion.

To address limitations in the current literature, the present meta-analysis was conducted to systematically compare the safety and efficacy of the two posterior approaches for multi-level CSM (LF vs EL) with regards to post-operative patient-rated scores and complication rates.

Methods

Literature search strategy

The present review was conducted according to the PRISMA guidelines [10, 11]. Electronic searches were performed using Ovid Medline, PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CCTR), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), ACP Journal Club and Database of Abstracts of Review of Effectiveness (DARE) from their dates of inception to January 2016. To achieve maximum sensitivity of the search strategy and to identify all studies, we combined the terms: “cervical”, “laminectomy”, and “laminoplasty” as either keywords or MeSH terms. The reference lists of all retrieved articles were reviewed for further identification of potentially relevant studies. All identified articles were systematically assessed using the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Selection criteria

Eligible comparative studies for the present systematic review and meta-analysis included: (1) patients undergoing extended laminoplasty (EL) or laminectomy and fusion (LF) and (2) patients with CSM caused by multi-segment spinal stenosis. When institutions published duplicate studies with accumulating numbers of patients or increased lengths of follow-up, only the most complete reports were included for quantitative assessment at each time interval. All publications were limited to those involving human subjects and in the English language. Abstracts, case reports, conference presentations, editorials and expert opinions were excluded. Review articles were omitted because of potential publication bias and duplication of results.

Data extraction and critical appraisal

All data were extracted from article texts, tables and figures. Two investigators independently reviewed each retrieved article (K.P. and V.L.). From the studies, extracted data included: (1) study design and description including country, study period, length of follow-up, patient distribution, (2) patient baseline demographics and comorbidities, (3) mean Japanese Orthopaedic Association (JOA) grade before and after posterior surgeries, (4) mean visual analogue scale (VAS) before and after surgery, (5) mean cervical curvature index (CCI) before and after surgery, and (6) complications including reoperations and nerve palsies. Discrepancies between the two reviewers were resolved by discussion and consensus with a third reviewer (R.J.M). Assessment of risk of bias for each selected study was performed according to the most updated Cochrane statement. Discrepancies between the two reviewers were resolved by discussion and consensus. The final results were reviewed by the senior investigator (R.J.M).

Statistical analysis

The weighted mean difference (WMD) and relative risk (RR) was used as a summary statistic. In the present study, both fixed- and random-effect models were tested. In the fixed-effects model, it was assumed that treatment effect in each study was the same, whereas in a random-effects model, it was assumed that there were variations between studies. χ2 tests were used to study heterogeneity between trials. I 2 statistic was used to estimate the percentage of total variation across studies, owing to heterogeneity rather than chance, with values greater than 50 % considered as substantial heterogeneity. I 2 can be calculated as: I 2 = 100 % × (Q − df)/Q, with Q defined as Cochrane’s heterogeneity statistics and df defined as degree of freedom. If there was substantial heterogeneity, the possible clinical and methodological reasons for this were explored qualitatively using remove-one-study sensitivity analysis, as well as sub-group analysis comparing RCT vs non-RCT studies. In the present meta-analysis, the results using the random-effects model were presented to take into account the possible clinical diversity and methodological variation between studies. Specific analyses considering confounding factors were not possible because raw data were not available. All P values were 2-sided. All statistical analysis was conducted with Review Manager Version 5.3 (Cochrane Collaboration, Software Update, Oxford, UK).

Quality of evidence and publication bias

Interstudy risk of publication bias was assessed using funnel plot methodology. The funnel plot represented the estimate (proportion of an event) in the x-axis vs its precision (inverse of the standard error of the estimate) in the y-axis. Significant asymmetry indicates potential publication bias, which may have affected the validity of presented results.

The checklist by Furlan et al. [12] was used to evaluate methodological quality of randomized controlled studies. Risk of bias assessment was performed using the checklist proposed by Cowley et al. [13] for non-randomized studies. The items were scored with “yes”, “no”, or “unclear”. A Furlan score of 6 or more out of a possible 12, or a Cowley score of 9 or more out of a possible 17, was considered to reflect “high methodological quality”. These studies were independently assessed by two reviewers, and any discrepancies were resolved by discussion and consensus.

Results

Quality of studies

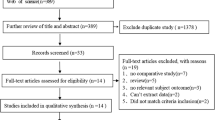

A total of 1035 references were identified through six electronic database searches. After exclusion of duplicate or irrelevant references, 1021 potentially relevant articles were retrieved. After detailed evaluation of these articles, 47 studies remained for detailed assessment. After applying selection criteria, 10 studies [5, 14–22] were selected for analysis (Fig. 1). The study characteristics of these trials are summarized in Table 1. From these 10 included studies, there were 335 patients who underwent laminectomy and fusion compared to 320 patients who underwent extended laminoplasty. Of these, two studies were prospective randomized trials [17, 22] whilst the remainder [5, 14–16, 18–21] were retrospective observational studies.

The mean age in the LF group ranged from 52.6 to 69.2 years, compared to the EL group, which ranged from 46.3 to 66.1 years. Overall, there was no significant difference in age between the groups (P = 0.08). The proportion of males was found to be similar between LF and EL groups (P = 0.25). Baseline JOA was found to be similar between the two groups (WMD −0.28, 95 % CI −0.96, 0.39, I 2 = 89 %, P = 0.41). Likewise, baseline VAS scores were similar between LF and EL groups (WMD 0.65, 95 % CI −1.15, 2.45, I 2 = 83 %, P = 0.48), as well as CCI. The average follow-up ranged from 12 to 110 months.

Assessment of JOA and VAS scores

Postoperative JOA score was reported in nine included studies. There was no significant difference found postoperatively between LF and EL groups (WMD −0.36, 95 % CI −1.19, 0.47, I 2 = 96 %, P = 0.39) (Fig. 2).

Postoperative VAS scores were reported in five studies. No significant difference in postoperative VAS score was found between LF and EL cohorts (WMD 0.05, 95 % CI −1.00, 1.10, I 2 = 89 %, P = 0.93).

Assessment of CCI

Postoperative CCI was reported in four studies. No significant difference was found between LF and EL groups (WMD 0.31, 95 % CI −0.30, 0.93, I 2 = 50 %, P = 0.32).

Assessment of Nurich grade

The postoperative Nurich grade was reported in two studies. There was no significant difference found between LF and EL cohorts (WMD −0.29, 95 % CI −1.00, 0.42, I 2 = 83 %, P = 0.42). Remove-one-study sensitivity analysis as well as RCT vs non-RCT subgroup analysis for assessment of JOA, VAS, CCI and Nurich outcomes did not demonstrate any significant change to the trends of the results presented.

Assessment of complications

From seven studies, the total complication rate was pooled (Fig. 3). A significantly higher complication rate was found for LF compared to EL (26.4 vs 15.4 %, RR 1.77, 95 % CI 1.10, 2.85, I 2 = 34 %, P = 0.02). Reoperation rate was reported in three studies. This rate was found to be similar between LF and EL groups (5.7 vs 4.9 %, RR 1.34, 95 % CI 0.55, 3.30, I 2 = 0 %, P = 0.52). For nerve palsies, a significantly higher pooled rate was found in the LF group compared to EL (9.9 vs 3.7 %, RR 2.76, 95 % CI 1.10, 6.92, I 2 = 26 %, P = 0.03).

Assessment of operative time and intraoperative blood loss

From 3 studies, no significant difference in operative time was determined (WMD 1.95 min, 95 % CI −39.95, 40.85, I 2 = 95 %, P = 0.92). Intraoperative blood loss was also similar between LF and EL cohorts (WMD −29.58 mL, 95 % CI −120.57, 61.42, I 2 = 98 %, P = 0.52).

Assessment of evidence quality

Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots (Fig. 4). Significant asymmetry was noted and detected, suggesting that publication bias was an influencing factor for the results of the present study.

In terms of risk of bias, the Furlan scores for the two included RCTs ranged from 6 to 8 points out of 12 (Table 2). All RCTs received Furlan scores of 6 or higher, indicating overall lower risk of bias in the randomized trials. The most notable shortcomings was unclear descriptions of patient blinding to intervention, care provide blinding to intervention, outcome assessor blinding to intervention, and compliance. The Cowley scores for the non-randomized studies ranged from 10 to 14 out of 17 (Table 3). All studies scored Cowley scores >9, demonstrating high methodological quality.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that LF and EF had similar postoperative patient-rated disability outcomes. There was no significant difference in JOA and VAS scores, with the assessment of CCI revealing comparable outcomes between the two surgical approaches. These results were consistent with a prior review and meta-analysis [23], which concluded that LF and EL lead to equivalent clinical improvement and loss of lordosis. The authors included that there is no evidence to support EL over LF in the treatment of multi-level CSM; however, the relative complication rates between the two approaches was not clearly established. In the present study, we demonstrated that the total complication rate in LF was around twofold higher than that of EF. In particular, LF was associated with significantly higher nerve palsy complications and trended towards higher reoperation rates.

Laminectomy is a widely used surgical procedure for CSM as it allows extensive decompression of the spinal cord. Overall, it is considered to be a safe and effective treatment method, with high overall rates of success ranging from 62 to 70 % [24]. However, laminectomy alone has been shown to compromise spinal column flexibility and stability especially at the lower level of laminectomy [25]. Subsequently, repetitive spinal cord microtrauma can result from this segmental instability, detrimentally affecting neurological results and long-term stability [26]. These clinical findings are supported by biomechanical studies on animals, which found that laminectomy resulted in a significant increase in forward sagittal angulation along with a decrease in spine stability along the sagittal plane [27]. Laminectomy is also not optimal in patients with congenitally short pedicles, due to the formation of post-laminectomy membranes [28, 29]. For these patients, while the procedure may initially decompress the spinal cord, the scar that forms over the dura mater can recompress the spinal cord as it adheres to the lateral masses and contracts [25].

More recently, laminectomy has been performed in conjunction with lateral mass fixation or fusion to address the post-operative instability that results from posterior lamina removal. The outcomes of laminectomy with posterior fusion or fixation have been promising, with lower detected levels of kyphosis, segmental instability and neurological deterioration [8]. However, cervical spine fusion compromises the natural biomechanics of spinal movement, causing axial and rotational forces to become unevenly distributed over adjacent spinal structures [20]. As a result of this, fusion procedures have been implicated with elevated levels of degeneration in adjacent spinal segments [30]. Screw loosening, screw avulsion and broken plates have also been reported in a few cases of laminectomy with cervical lateral mass screws/plates for fixation/fusion [9, 31].

To address the issues of segmental instability, late kyphosis, and neurological deficits from a combined laminectomy and fusion approach, laminoplasty was developed as to surgically treat multilevel CSM with lower levels of late deformity and neurological defects. In laminoplasty, the main advantage stems from the fact that the laminae are still available for load bearing and attachment of paraspinous muscles [32]. In fact, animal models showed that a spine treated with laminoplasty was very similar to that of an intact spine [27]. Thus, the natural biomechanics of spinal movements are preserved following laminoplasty, reducing the risk of spinal segment deterioration, daily microtrauma and instability [25]. Along with that, laminae retention in laminoplasty also prevents the formation of a post-laminectomy membrane, which can recompress the spinal cord [29]. Complications of laminoplasty have been reported to include neck spasms and shoulder pain. Another potential complication occurring in 5–11 % of laminoplasty patients is motor dominant C5 root palsy [33]. It is hypothesized that laminoplasty can cause posterior drift at the level of C5, placing the C5 nerve root under stretch and causing the palsy [34]. Mechanical tethering of the nerve root in the foramina with concurrent posterior cord migration may stretch the C5 nerve and further exacerbate the palsy. This theory; however, does not provide an explanation as to why C5 palsies still occur following anterior decompression. In contrast for posterior reconstruction surgery, Kurakawa et al. [35] demonstrated correction angle and preoperative diameter of the C4/5 intervertebral foramen as predictors of C5 palsy, following multivariate adjustment for confounders. Ultimately, while surgical management of CSM has advanced greatly over the years, all our current treatment options still present various potential complications.

The analysis of our current study is limited by a few factors. The studies included, consisted of both randomized and non-randomized observational studies. This presents the issue of selection bias, which limits the internal validity of our findings. There were also underlying baseline differences in the various studies, with some patients already with preoperative kyphosis and segmental stability. This can contribute to the underestimation or overestimation of the actual effect of a surgical procedure delivered. Across centers, there were also variations in the technical nuances of the surgical procedure, with laminoplasty being performed with different techniques such as French door and open door. Along with that unstandardized reporting for quality and satisfaction of outcomes was also a limiting factor. Recent studies have also suggested that sagittal alignment may affect surgical outcome in degenerative cervical myelopathy for different approaches [36, 37]. Based on a comparative analysis of three techniques, Koda et al. [36] suggested that posterior or anterior decompression and fusion but not laminoplasty may be used for K-line cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. The impact of preoperative sagittal alignment on postoperative outcomes in the present meta-analysis could not be assessed due to the nature of data reported by the included studies. A lack of heterogeneity in regards to follow-up period also makes it difficult to make definitive conclusions about the long-term efficacy of the two surgical approaches. For example, late neurological deterioration is a known complication of laminoplasty for cervical spondylotic myelopathy [38]. These factors all add uncontrollable bias to our findings. Ideally, to minimize bias the operative technique, defined outcomes and follow-up period should be standardized across all cases.

Conclusions

From the available low-quality evidence, LF and EL approaches for CSM demonstrates similar clinical improvement and loss of lordosis. However, a twofold higher complication was found in LF group, including significantly higher nerve palsy complications. This requires further validation and investigation in larger sample-size prospective and randomized studies.

References

Broughton E (2015) Cervical spondylotic myelopathy. In: Challenging concepts in neurosurgery: cases with expert commentary. Oxford University Press

Liu Y, Hou Y, Yang L et al (2012) Comparison of 3 reconstructive techniques in the surgical management of multilevel cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Spine 37:E1450–E1458

Rao RD, Gourab K, David KS (2006) Operative treatment of cervical spondylotic myelopathy. J Bone Joint Surg Am 88:1619–1640

Kawakami M, Tamaki T, Iwasaki H et al (2000) A comparative study of surgical approaches for cervical compressive myelopathy. Clin Orthop Relat Res 381:129–136

Highsmith JM, Dhall SS, Haid RW Jr et al (2011) Treatment of cervical stenotic myelopathy: a cost and outcome comparison of laminoplasty vs laminectomy and lateral mass fusion: clinical article. J Neurosurg Spine 14:619–625

Guigui P, Benoist M, Deburge A (1998) Spinal deformity and instability after multilevel cervical laminectomy for spondylotic myelopathy. Spine 23:440–447

Guigui P, Lefevre C, Lassale B (1998) et al Static and dynamic changes of the cervical spine after laminectomy for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot 84:17–25

Kumar VGR, Rea GL, Mervis LJ et al (1999) Cervical spondylotic myelopathy: functional and radiographic long-term outcome after laminectomy and posterior fusion. Neurosurgery 44:771–777

Heller JG, Edwards CC, Murakami H et al (2001) Laminoplasty vs laminectomy and fusion for multilevel cervical myelopathy: an independent matched cohort analysis. Spine 26:1330–1336

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6:e1000097

Phan K, Mobbs RJ (2015) Systematic reviews and meta-analyses in spine surgery, neurosurgery and orthopedics: guidelines for the surgeon scientist. J Spine Surg 1:19–27

Furlan AD, Pennick V, Bombardier C et al (2009) Updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane Back Review Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 34:1929–1941

Cowley DE (1995) Prostheses for primary total hip replacement. A critical appraisal of the literature. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 11:770–778

Chen Y, Liu X, Chen D et al (2012) Surgical strategy for ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament in the cervical spine. Orthopedics (Online) 35:e1231

Du W, Wang L, Shen Y et al (2013) Long-term impacts of different posterior operations on curvature, neurological recovery and axial symptoms for multilevel cervical degenerative myelopathy. Eur Spine J 22:1594–1602

Lee CH, Jahng TA, Hyun SJ et al (2014) Expansive laminoplasty vs laminectomy alone vs laminectomy and fusion for cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: is there a difference in the clinical outcome and sagittal alignment? J Spinal Disord Tech 29:E9–E15

Manzano GR, Casella G, Wang MY et al (2012) A prospective, randomized trial comparing expansile cervical laminoplasty and cervical laminectomy and fusion for multilevel cervical myelopathy. Neurosurgery 70:264–277

Ren DJ, Li F, Zhang ZC et al (2015) Comparison of functional and radiological outcomes between two posterior approaches in the treatment of multilevel cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Chin Med J 128:2054–2058

Sivaraman A, Bhadra AK, Altaf F et al (2010) Skip laminectomy and laminoplasty for cervical spondylotic myelopathy: a prospective study of clinical and radiologic outcomes. J Spinal Disord Tech 23:96–100

Woods BI, Hohl J, Lee J et al (2011) Laminoplasty vs laminectomy and fusion for multilevel cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Clin Orthop Relat Res 469:688–695

Yang L, Gu Y, Shi J et al (2013) Modified plate-only open-door laminoplasty vs laminectomy and fusion for the treatment of cervical stenotic myelopathy. Orthopedics 36:e79–e87

Yukawa Y, Kato F, Ito K et al (2007) Laminoplasty and skip laminectomy for cervical compressive myelopathy: range of motion, postoperative neck pain, and surgical outcomes in a randomized prospective study. Spine 32:1980–1985

Lee CH, Lee J, Kang JD et al (2015) Laminoplasty vs laminectomy and fusion for multilevel cervical myelopathy: a meta-analysis of clinical and radiological outcomes. J Neurosurg Spine 22:589–595

Phan K, Mobbs RJ (2016) Minimally invasive vs open laminectomy for lumbar stenosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 41:E91–E100

Geck MJ, Eismont FJ (2002) Surgical options for the treatment of cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Orthop Clin North Am 33:329–348

Cusick JF, Pintar FA, Yoganandan N (1995) Biomechanical alterations induced by multilevel cervical laminectomy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 20:2392–2398 (discussion 8–9)

Baisden J, Voo LM, Cusick JF et al (1999) Evaluation of cervical laminectomy and laminoplasty: A longitudinal study in the goat model. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 24:1283–1288 (discussion 8–9)

Mayfield FH (1976) Complications of laminectomy. Clin Neurosurg 23:435–439

Yonenobu K, Hosono N, Iwasaki M et al (1991) Neurologic complications of surgery for cervical compression myelopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 16:1277–1282

Kato Y, Iwasaki M, Fuji T et al (1998) Long-term follow-up results of laminectomy for cervical myelopathy caused by ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. J Neurosurg 89:217–223

Heller JG, Silcox DH 3rd, Sutterlin CE 3rd (1995) Complications of posterior cervical plating. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 20:2442–2448

Pal GP, Routal RV (1996) The role of the vertebral laminae in the stability of the cervical spine. J Anat 188(Pt 2):485–489

Braly BA, Lunardini D, Cornett C et al (2012) Operative treatment of cervical myelopathy: cervical laminoplasty. Adv Orthop 2012:508534

Sodeyama T, Goto S, Mochizuki M et al (1999) Effect of decompression enlargement laminoplasty for posterior shifting of the spinal cord. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 24:1527–1531 (discussion 31–2)

Kurakawa T, Miyamoto H, Kaneyama S, et al (2016) C5 nerve palsy after posterior reconstruction surgery: predictive risk factors of the incidence and critical range of correction for kyphosis. Eur spine J ( Epub ahead of print)

Koda M, Mochizuki M, Konishi H, et al (2016) Comparison of clinical outcomes between laminoplasty, posterior decompression with instrumented fusion, and anterior decompression with fusion for K-line (–) cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Eur spine J ( Epub ahead of print)

Kato S, Fehlings M (2016) Degenerative cervical myelopathy. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med ( Epub ahead of print)

Sakaura H, Miwa T, Kuroda Y et al (2016) Incidence and risk factors for late neurologic deterioration after C3–C6 laminoplasty for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Glob Spine J 6:53–59

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None of the authors has any potential conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Phan, K., Scherman, D.B., Xu, J. et al. Laminectomy and fusion vs laminoplasty for multi-level cervical myelopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Spine J 26, 94–103 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-016-4671-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-016-4671-5