Abstract

Background

Cervical spondylotic myelopathy is frequently encountered in neurosurgical practice. The posterior surgical approach includes laminectomy and laminoplasty.

Objective

To perform a systematic review evaluating the effectiveness of posterior laminectomy compared with posterior laminoplasty for patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy.

Methods

An extensive search of the literature in Pubmed, Embase, and Cochrane library was performed by an experienced librarian. Risk of bias was assessed by two authors independently. The quality of the studies was graded, and the following outcome measures were retrieved: pre- and postoperative (m)JOA, pre- and postoperative ROM, postoperative VAS neck pain, and Ishira cervical curvature index. If possible data were pooled, otherwise a weighted mean was calculated for each study and a range mentioned.

Results

All studies were of very low quality. Due to inadequate description of the data in most articles, pooling of the data was not possible. Qualitative interpretation of the data learned that there were no clinically important differences, except for the higher rate of procedure-related complications with laminoplasty.

Conclusion

Based on these results, a claim of superiority for laminoplasty or laminectomy was not justified. The higher number of procedure-related complications should be considered when laminoplasty is offered to a patient as a treatment option. A study of robust methodological design is warranted to provide objective data on the clinical effectiveness of both procedures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cervical spondylotic myelopathy refers to clinical changes that frequently are related to compression of the spinal cord due to degenerative spinal stenosis. With people growing older, an increase of patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy is expected. The natural course is often poor. With surgical decompression, a stabilization of neurological deficit or even recovery may take place in the majority of the patients. Surgical decompression can be performed either anteriorly, posteriorly or both approaches combined and is variably supplemented by additional fusion. Discussion about the best anatomical approach is beyond the scope of this article.

However, when considering the posterior approach, two methods are usually being applied. The oldest posterior approach is laminectomy, which can be performed with or without fusion [1]. Recently, a modification has been introduced which is called skip laminectomy [2]. In skip laminectomy, standard laminectomies are performed in combination with partial laminectomies of selected laminae to leave the muscular attachments undisturbed.

The other posterior approach is laminoplasty. In English literature, it was first described by Tsuji in 1982 [3], although different kinds of laminoplasty were described in 1973 [4], in 1978 [5], and in 1982 [6].

Laminoplasty might prevent postoperative spinal deformities which were seen after laminectomy [3]. Laminoplasty is technically more demanding, and if implants are used it is more expensive than laminectomy. Currently, as noticed in meetings and courses, more and more surgeons seem to perform laminoplasty.

This meta-analysis was performed to investigate whether a difference exists in clinical outcome, radiological outcome and complication rate between non-instrumented laminectomy and laminoplasty for cervical spondylotic myelopathy.

Methods

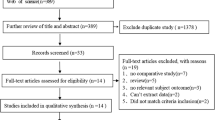

A highly sensitive search strategy was performed by an experienced librarian in Pubmed, Embase, and the Cochrane library including a search with Mesh or thesaurus terms complemented with a free text search in the title and abstracts (see Table 1). Since the first report that could be retrieved in Pubmed or Embase was published in 1982 [3], the search started in that year (Fig. 1).

Only articles published in Dutch, English, German or French were included. The goal was to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs). However, if we would identify less than three RCTs, observational studies were also included.

Inclusion criteria were adult patients suffering from cervical spondylotic myelopathy, treatment consisting of either non-instrumented laminectomy or laminoplasty, series of more than or equal to 20 cases in either group, and score according to the Japanese Orthopedic Association (JOA) or its modification (mJOA) as an outcome measurement.

Two review authors (MA and WM) independently assessed titles and abstracts for possible inclusion. If they did not agree, the opinion of a third (WP) reviewer was obtained. Subsequently, full text versions were retrieved and assessed by the same two review authors independently. The reference lists were checked for additional articles.

The following outcome measurement was considered as primary outcome: JOA or mJOA. The maximum score of both scales is 17 and the subdivision in the original and modified scale is similar. Secondary outcomes were VAS neck pain, complication rate, SF 36, EQ5d, SF 12, ROM, Ishihara’s cervical curvature index [7] and specification of complications.

The risk of bias was assessed using the criteria proposed by the Cochrane Back Review Group [8]. The level of evidence was assessed according to the guidelines of the GRADE working group [9–11].

SPSS 20 (IBM Corporation, North Castle Drive, Armonk, NY 10504-1785, USA) was used for statistical analyses. We calculated weighted means taking into account the sample size of the study and its mean with a range of the reported means.

If not provided by the article, the recovery rate according to Hirabayashi [12] was calculated: recovery rate (%) = (postoperative (m)JOA − preoperative (m)JOA)/(17 − preoperative (m)JOA) × 100.

Results

After removing duplicates, 813 references to studies were identified. Finally, the full text versions of 68 articles were retrieved. After careful review of these articles, 29 [2, 13–40] were finally selected and included in this systematic review. Only one was a RCT comparing laminoplasty with a modification of laminectomy [40]. Since the goal of the systematic review was to compare laminectomy versus laminoplasty, randomized controlled studies of two forms of laminoplasty were considered as two prospective cohorts describing the similar outcomes and also included in the review. Most articles reported a mean without any standard deviation and, therefore, a meta-analysis was not possible.

For all studies, the risk of bias was considered high. The RCTs [27, 40] did not report the process of randomization, allocation, blinding or dealing with missing data. The risk of bias of the studies is presented in Table 2. Since the observational studies were not methodologically rigorous, the quality of evidence using GRADE was not upgraded and remained very low [41].

Since some articles reported the results of two cohorts of patients, these 29 articles represented 35 cohorts of a total of 1492 patients. The weighted mean age was 60.8 years (51–83 years) and mean follow-up 42 months (12–158 months) postoperatively. Six articles did not report the male to female ratio [15, 19, 22, 24, 26, 31]. In the remaining 1215 patients, the male to female ratio was 810/405. Baseline characteristics of the two treatment groups are presented in Table 3.

There were no clinically important differences in pre- and postoperative (m)JOA, pre- and postoperative ROM, and Ishihara indices (Tables 4, 5, 6, 7).

All studies showed clinical improvement after surgical intervention. The overall mean Hirabayashi index was 56.9 % (35.6–73.9), for laminoplasty 57.2 % (35.6–73.9), for not skip laminectomy 54.6 % (45.8–66.7), and for skip laminectomy 55.6 % (50.7–60.5). The preoperative VAS was only reported in four cohorts and the postoperative VAS in six. All articles reported on laminoplasty. The mean pre-operative VAS for neck pain was 4.0 (1.4–6) and the mean postoperative VAS was 3.0 (1–4.6). None of the studies reported results on quality of life.

Discussion

Three posterior modalities exist for the treatment of cervical spondylotic myelopathy: laminoplasty, laminectomy, and skip laminectomy. These techniques can be supplemented by additional fusion.

From a biomechanical point of view, laminoplasty and laminectomy are similar. In both techniques, the muscles are widely dissected and ligamentous structures transected. The lamina are removed or opened. During this action damage to surrounding tissue (joints) might occur. Laminoplasty has an even higher risk of complications if the lamina is fixed with implants to the lateral mass (warranting wider dissection). The skip laminectomy is different compared with laminoplasty, since not all ligamentous attachments are sacrificed but preserved at selected spinous processes. Laminectomies are also restricted to the levels of compression and, therefore, not standard from C3 to C7 anymore.

The clinical results, the postoperative ROM, and the prevalence of a postoperative kyphotic deformity did not differ between the groups. Since a posterior approach is generally performed when the cervical curvature is lordotic, we feel confident to conclude that a difference of 6 % is clinically not important and that from this analysis it was not apparent that more kyphotic deformity occurred in the laminectomy group. None of the studies reported uniformly whether a kyphotic deformity occurred. Therefore, a more detailed analysis was not possible. This result corresponds with what you would expect from a biomechanical point of view.

Postoperative neck pain was only reported in a few studies. Some studies showed a benefit of preserving the lamina of C7 for reducing postoperative axial pain [20, 33, 35]. In a recent review, however, it was concluded that several factors may contribute to postoperative neck pain after posterior cervical surgery, but the evidence was not convincing. Definite conclusions were not possible due to the lack of uniform design of the studies and poor presentation of the results [42].

General complications seemed to be highly similar in both groups. Complications as hardware failure or malpositioning, and closing of the lamina will only occur with laminoplasty. This is a serious consideration when opting for laminoplasty.

This systematic review has some limitations. We only identified one RCT that compared laminoplasty and laminectomy, so we mainly had to rely upon data from observational studies. The quality of the studies was very low. The presentation of the results was also poor and, therefore, we were not able to perform a meta-analysis.

Considering the limitations of this systematic review and of the original studies, strong conclusions are not opportune. Due to the high risk of bias of the studies and the low quality of evidence, it is evident that at present none of the procedures has performed better than the other on clinical outcomes, postoperative axial neck pain or postoperative kyphotic deformity. However, the complication rate of laminoplasty seemed higher.

Laminoplasty is a relatively new surgical approach, which is propagated at the expense of laminectomy during courses and scientific meetings. This systematic review showed that laminoplasty has been introduced without any sound scientific support. In our opinion, laminoplasty should still be considered a new technique and cervical laminectomy as usual care. A well-designed RCT with a low risk of bias and an adequate sample size comparing laminectomy versus laminoplasty is necessary to evaluate which surgical method is performing better on clinical results (including patient reported outcomes) and complication rate. This systematic review presented some troublesome results. For a serious neurological threatening degenerative disorder with growing societal impact caused by an aging population and the global wish to stay mobile up to high age, the scientific evidence for any surgical approach is lacking. We strongly recommend performing an economic evaluation alongside this trial to evaluate which technique is most cost-effective. We are obliged to our patients to inform them properly about the safety and quality of our surgical actions.

References

Denaro V, Di Martino A (2011) Cervical spine surgery: an historical perspective. Clin Orthop Relat Res 469:639–648

Shiraishi T (2002) Skip laminectomy—a new treatment for cervical spondylotic myelopathy, preserving bilateral muscular attachments to the spinous processes: a preliminary report. Spine J 2:108–115

Tsuji H (1982) Laminoplasty for patients with compressive myelopathy due to so-called spinal canal stenosis in cervical and thoracic regions. Spine 7:28–34

Oyama M, Hattori S, Moriwaki N (1973) A new method of posterior decompression [in Japanese]. Centr Jpn J Orthop Traumatol Surg (Chubuseisaisi) 16:792–794

Hirabayashi K (1978) Expansive open-door laminoplasty for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Shujutsu 32:1159–1163

Kurokawa T, Tsuyama N, Tanaka H (1982) Enlargement of spinal canal by the sagittal splitting of the spinous process. Bessatusu Seikeigeka 2:234–240

Ishihara A (1968) Roentenographic studies on the normal pattern of the cervical curvature. Nippon Seikeigeka Gakkai Zasshi 42:1033–1044 (in Japanese)

Furlan AD, Pennick V, Bombardier C, van Tulder M, Editorial Board CBRG (2009) 2009 updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane Back Review Group. Spine 34:1929–1941

Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, Kunz R, Vist G, Brozek J, Norris S, Falck-Ytter Y, Glasziou P, DeBeer H, Jaeschke R, Rind D, Meerpohl J, Dahm P, Schunemann HJ (2011) GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol 64:383–394

Balshem H, Helfand M, Schunemann HJ, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Brozek J, Vist GE, Falck-Ytter Y, Meerpohl J, Norris S, Guyatt GH (2011) GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 64:401–406

Guyatt GHOA, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, GRADE Working Group (2008) GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 336:924–926

Hirabayashi K, Miyakawa J, Satomi K, Maruyama T, Wakano K (1981) Operative results and postoperative progression among patients with ossification among patients with ossification of cervical posterior longitudinal ligament. Spine 6:354–364

Chung SS, Lee CS, Chung KH (2002) Factors affecting the surgical results of expansive laminoplasty for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. IntOrthop 26:334–338

Guigui P, Benoist M, Deburge A (1998) Spinal deformity and instability after multilevel cervical laminectomy for spondylotic myelopathy. Spine 23:440–447

Hamanishi C, Tanaka S (1996) Bilateral multilevel laminectomy with or without posterolateral fusion for cervical spondylotic myelopathy: relationship to type of onset and time until operation. J Neurosurg 85:447–451

Han G-W, Liu S-Y, Liang C-X, Yu B-S, Chen B-L, Zhang X-H, Li H-M, Wei F-X (2009) Application of hydroxyapatite artificial bone in bilateral open-door posterior cervical expansive laminoplasty. J Clin Rehabil Tissue Eng Res 13:5661–5664

Handa Y, Kubota T, Ishii H, Sato K, Tsuchida A, Arai Y (2002) Evaluation of prognostic factors and clinical outcome in elderly patients in whom expansive laminoplasty is performed for cervical myelopathy due to multisegmental spondylotic canal stenosis. A retrospective comparison with younger patients. J Neurosurg 96:173–179

Hatta Y, Shiraishi T, Hase H, Yato Y, Ueda S, Mikami Y, Harada T, Ikeda T, Kubo T (2005) Is posterior spinal cord shifting by extensive posterior decompression clinically significant for multisegmental cervical spondylotic myelopathy? Spine 30:2414–2419

Highsmith JM, Dhall SS, Haid RW Jr, Rodts GE Jr, Mummaneni PV (2011) Treatment of cervical stenotic myelopathy: a cost and outcome comparison of laminoplasty versus laminectomy and lateral mass fusion. J Neurosurg Spine 14:619–625

Hosono N, Sakaura H, Mukai Y, Fujii R, Yoshikawa H (2006) C3–6 laminoplasty takes over C3–7 laminoplasty with significantly lower incidence of axial neck pain. Eur Spine J 15:1375–1379

Inoue H, Ohmori K, Ishida Y, Suzuki K, Takatsu T (1996) Long-term follow-up review of suspension laminotomy for cervical compression myelopathy. J Neurosurg 85:817–823

Kawaguchi Y, Kanamori M, Ishihara H, Ohmori K, Nakamura H, Kimura T (2003) Minimum 10-year followup after en bloc cervical laminoplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 411:129–139

Liu J, Ebraheim NA, Sanford CG Jr, Patil V, Haman SP, Ren L, Yang H (2007) Preservation of the spinous process-ligament-muscle complex to prevent kyphotic deformity following laminoplasty. Spine J 7:159–164

Motosuneya T, Maruyama T, Yamada H, Tsuzuki N, Sakai H (2011) Long-term results of tension-band laminoplasty for cervical stenotic myelopathy: a ten-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br 93:68–72

Naderi S, Ozgen S, Pamir MN, Ozek MM, Erzen C (1998) Cervical spondylotic myelopathy: surgical results and factors affecting prognosis. Neurosurgery 43:43–49

Naruse T, Yanase M, Takahashi H, Horie Y, Ito M, Imaizumi T, Oguri K, Matsuyama Y (2009) Prediction of clinical results of laminoplasty for cervical myelopathy focusing on spinal cord motion in intraoperative ultrasonography and postoperative magnetic resonance imaging. Spine 34:2634–2641

Okada M, Minamide A, Endo T, Yoshida M, Kawakami M, Ando M, Hashizume H, Nakagawa Y, Maio K (2009) A prospective randomized study of clinical outcomes in patients with cervical compressive myelopathy treated with open-door or French-door laminoplasty. Spine 34:1119–1126

Sakai Y, Matsuyama Y, Inoue K, Ishiguro N (2005) Postoperative instability after laminoplasty for cervical myelopathy with spondylolisthesis. J Spinal Disord Tech 18:1–5

Satomi K, Nishu Y, Kohno T, Hirabayashi K (1994) Long-term follow-up studies of open-door expansive laminoplasty for cervical stenotic myelopathy. Spine 19:507–510

Suda K, Abumi K, Ito M, Shono Y, Kaneda K, Fujiya M (2003) Local kyphosis reduces surgical outcomes of expansive open-door laminoplasty for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Spine 28:1258–1262

Suzuki A, Misawa H, Simogata M, Tsutsumimoto T, Takaoka K, Nakamura H (2009) Recovery process following cervical laminoplasty in patients with cervical compression myelopathy: prospective cohort study. Spine 34:2874–2879

Takayama H, Muratsu H, Doita M, Harada T, Kurosaka M, Yoshiya S (2005) Proprioceptive recovery of patients with cervical myelopathy after surgical decompression. Spine 30:1039–1044

Takeuchi T, Shono Y (2007) Importance of preserving the C7 spinous process and attached nuchal ligament in French-door laminoplasty to reduce postoperative axial symptoms. EurSpine J 16:1417–1422

Tanaka N, Nakanishi K, Fujimoto Y, Sasaki H, Kamei N, Hamasaki T, Yamada K, Yamamoto R, Nakamae T, Ochi M (2009) Clinical results of cervical myelopathy in patients older than 80 years of age: evaluation of spinal function with motor evoked potentials. J Neurosurg Spine 11:421–426

Tsuji T, Asazuma T, Masuoka K, Yasuoka H, Motosuneya T, Sakai T, Nemoto K (2007) Retrospective cohort study between selective and standard C3–7 laminoplasty. Minimum 2-year follow-up study. Eur Spine J 16:2072–2077

Wan J, Xu T–T, Shen Q-F, Li H-N, Xia Y-P (2011) Influence of hinge position on the effectiveness of open-door expansive laminoplasty for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Chin J Traumatol English Edition 14:36–41

Yagi M, Ninomiya K, Kihara M, Horiuchi Y (2010) Long-term surgical outcome and risk factors in patients with cervical myelopathy and a change in signal intensity of intramedullary spinal cord on magnetic resonance imaging: Clinical article. J Neurosurg Spine 12:59–65

Yamazaki T, Yanaka K, Sato H, Uemura K, Tsukada A, Nose T (2003) Cervical spondylotic myelopathy: surgical results and factors affecting outcome with special reference to age differences. Neurosurgery 52:122–126

Yue WM, Tan CT, Tan SB, Tan SK, Tay BK (2000) Results of cervical laminoplasty and a comparison between single and double trap-door techniques. J Spinal Disord 13:329–335

Yukawa Y, Kato F, Ito K, Horie Y, Hida T, Ito Z, Matsuyama Y (2007) Laminoplasty and skip laminectomy for cervical compressive myelopathy: range of motion, postoperative neck pain, and surgical outcomes in a randomized prospective study. Spine 32:1980–1985

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Sultan S, Glasziou P, Akl EA, Alonso-Coello P, Atkins D, Kunz R, Brozek J, Montori V, Jaeschke R, Rind D, Dahm P, Meerpohl J, Vist G, Berliner E, Norris S, Falck-Ytter Y, Murad MH, Schunemann HJ, Group GW (2011) GRADE guidelines: 9. Rating up the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 64:1311–1316

Wang SJ, Jiang SD, Jiang LS, Dai LY (2011) Axial pain after posterior cervical spine surgery: a systematic review. Eur Spine J 20:185–194

Conflict of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bartels, R.H.M.A., van Tulder, M.W., Moojen, W.A. et al. Laminoplasty and laminectomy for cervical sponydylotic myelopathy: a systematic review. Eur Spine J 24 (Suppl 2), 160–167 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-013-2771-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-013-2771-z