Abstract

Purpose

We performed a retrospective analysis of all cases of lumbo-sacral or sacral metastases presenting with compression of the cauda equina who underwent urgent surgery at our institution. Our objective was to report our experience on the clinical presentation, management and finally the surgical outcome of this cohort of patients.

Methods

We reviewed medical notes and images of all patients with compression of the cauda equina as a result of lumbo-sacral or sacral metastases during the study period (2004–2011). The collected clinical data consisted of time of onset of symptoms, neurology (Frankel grade), ambulatory status and continence. Operative data analysed were details of surgical procedure and complications. Post-operatively, we reviewed neurological outcome, ambulation, continence, destination of discharge and survival.

Results

During the 8-year study period, 20 patients [11 males, 9 females; mean age 61.8 years (29–87)] had received urgent surgery for metastatic spinal cauda compression caused by lumbo-sacral or sacral metastases. The majority of patients presented with symptoms of pain and neurological deterioration (n = 14) with onset of pain considerably longer than neurology symptoms [197 days (3–1,825) vs. 46 days (1–540)]; all patients were Frankel C (n = 2, both non-ambulatory), D (n = 13) or E (n = 5) at presentation and three patients were incontinent of urine. Operative procedures performed were posterior decompression with (out) fusion (n = 12), posterior decompression with sacroplasty (n = 1), decompression with lumbo-pelvic stabilisation with (out) kyphoplasty/sacroplasty (n = 7) and posterior decompression/reconstruction with anterior corpectomy/stabilisation (n = 2). Post-operatively, 5/20 (20 %) patients improved one Frankel grade, 1/20 (5 %) improved two grades, 13/20 (65 %) remained stable (8 D, 5 E) and 1/20 (5 %) deteriorated. All patients were ambulatory and 19/20 were continent on discharge. The mean length of stay was 7 days (4–22). There were 6/20 (30 %) complications: three major (PE, deep wound infection, implant failure) and three minor (superficial wound infection, incidental durotomy, chest infection). All patients returned back to their own home (n = 14/20, 70 %) or a nursing home (n = 6/20, 35 %). Thirteen patients are deceased (mean survival 367 days (120–603) and seven are still alive [mean survival 719 days (160–1,719)].

Conclusion

Surgical intervention for MSCC involving the lumbo-sacral junction or sacral spine has a high but acceptable complication rate (6/20, 30 %), and can be important in restoring/preserving neurological function, assisting with ambulatory function and allowing patients to return to their previous residence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Spinal metastases develop in 5–10 % of all cancer patients during the course of their illness [1]. Sacral deposits represent the minority of spinal secondaries [2] which predominantly infiltrate the thoracic region, followed by the lumbar and the cervical spine. Breast, lung, renal, thyroid and prostate tumours form the predominant primary sources [3, 4]. Other less common primary lesions include lymphoma, myeloma/plasmacytoma, melanoma and tumours of unknown origin. The timing between primary and spinal metastases varies according to the site and nature of the primary. Spread is mainly by haematogenous dissemination, [1] although direct invasion through locally recurrent pelvic tumours is not uncommon.

Even though the majority of sacral neoplasms are benign [1], malignant sacral tumours mainly occur as a result of metastatic spread from nearby pelvic or distant sites [1, 3, 4]. Most spinal metastatic lesions are localised in the anterior portion of the vertebral body and less frequently in the pedicle or lamina. Pain is the predominant initial symptom followed by impaired neurology including loss of bowel control, urinary incontinence, sexual dysfunction and lower extremity weakness [5]. Local and radicular pain can be relieved by resecting the tumour and decompressing the neural elements. Radiosensitivity varies among primary tumour types. Prostate and lymphoid tumours are radiosensitive, breast cancer is 70 % sensitive and 30 % resistant and gastrointestinal and renal cell tumours, such as melanomas, are radio-resistant. Radiotherapy with (out) vascular angioembolization may still result in a high rate of disease recurrence [4].

Indications for surgical intervention include progressive neurologic dysfunction or persistent pain that is unresponsive to radiation therapy, the need for a diagnostic biopsy and pathologic instability [6]. It must be noted that ideally, radiotherapy should not be used before surgery because of problems with wound healing that can occur. In these cases, close cooperation between the spine surgeons and oncologists, as well as regular MDT meetings are essential. The assistance of a metastatic spine cancer coordinator (as per NICE guidelines) is also an invaluable asset [7]. Vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty is gaining favour in cases of metastatic disease without instability or neurologic compromise, and represents a minimally invasive alternative to open procedures [6]. Our previous review has summarised all the available literature for the management of these patients [8]. This showed the relative paucity of studies dealing with this pathology as well as its uncertain outcome. This current study describes our experience in the management of this cohort group who underwent emergency surgery. We discuss their initial clinical presentation, treatment and finally the surgical outcome.

Materials and methods

We reviewed all medical notes and images of patients with compression of the cauda equina as a result of lumbo-sacral and sacral metastases during the study period (2004–2011). The collected clinical data consisted of time of onset of symptoms, neurology, ambulatory status and continence. We used the Frankel grade to record neurology as this is a commonly understood grading system for impairment due to neurological damage to the spine (although perhaps superseded by the ASIA Impairment score now). The operative data analysed included details of surgical procedure and complications. Post-operatively, we reviewed patients’ neurological outcome, ambulatory status, continence, destination of discharge and survival.

Exclusion criteria included patients treated solely with radiotherapy, patients having a cement augmentation procedure without decompression and patients who had undergone previous surgery for spinal metastasis. Research approval was not required as this study was conducted for ‘service evaluation’ as per our hospitals’ guidelines. Detailed statistical analysis was not performed due to the small number of patients (as a result of the relative rarity of this condition).

Results

General demographic and tumour data

During the 8-year study period, 20 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria. There were 11 men and 9 women with a mean age of 61.8 years (29–87) (Table 1). The metastatic lesions were located in the lumbo-sacral region (L5–S1; n = 10, 50 %), the sacrum (S1–S5; n = 6, 30 %) and multiple sites from the lumbo-sacral spine to whole sacrum (n = 4, 20 %).

The primary tumours are shown in Table 1. Renal cell carcinoma (RCC: n = 6, 30 %) and those from the gastrointestinal tract (n = 5, 25 %) accounted for just over half of the metastases.

Clinical presentation

The majority of patients presented with a long history of back pain (197 days, range 3–1825), whilst neurological symptoms were of shorter duration [46 days (1–540)] including radicular symptoms in 11/20 (55 %) and combined neurology with radiculopathy and some bowel/bladder problems in 6/20 (30 %) (Table 1). Three out of 20 (15 %) patients had lost bowel/bladder control and two patients were non-ambulatory at presentation. Neurologically, 18/20 (90 %) patients were Frankel D/E (Frankel D, n = 13/20; Frankel E, n = 5/20). Two (10 %) patients were Frankel grade C. Five patients with metastatic RCC underwent pre-operative embolization to reduce the intra-operative blood loss [9–11] and their surgery was performed within 24 h. Two patients had received pre-operative radiotherapy (Case nos. 16 and 20), and three patients had undergone pre-operative chemotherapy (Case nos. 2, 15, 17) for metastases.

Operative procedure

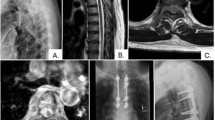

A posterior approach was utilised in the majority of our patients (n = 18/20, 90 %): 12/20 (60 %) patients had a posterior decompression with (out) stabilisation, 7/20 (35 %) patients underwent posterior decompression with lumbo-pelvic stabilisation (Table 1). This required fixation of the lumbar spine to the iliac wings to span the diseased sacrum. One patient (5 %) had a decompression and sacroplasty and two (10 %) patients had a posterior decompression/reconstruction with anterior corpectomy/stabilisation (Fig. 1). Bone graft (allograft) was used only in one case and BMP-2 (Inductos, Medtronic®) also in one patient. Post-operatively, radiotherapy was performed in ten patients (2 patients received radiotherapy in combination with chemotherapy); five patients received chemotherapy only and five patients did not receive any adjuvant treatment.

A 45 year old female patient presenting with symptoms of cauda equina compression (Frankel C). a Sagittal T1 and T2 weighted MRI showing metastasis at L5/S1, b post-operative AP and lateral X-rays showing stabilization from L3 to pelvis and anterior corpectomy reconstructed with an expandable cage. Histology confirmed this to be RCC (she also went on to have a laparoscopic nephrectomy). She remains well at 2.5 years follow-up (Frankel E)

Clinical outcome and complications

Post-operatively, 5/20 (20 %) patients improved one Frankel grade (4 D→E, 1 C→D), 1/20 (5 %) improved by two grades (C→E), 13/20 (65 %) remained stable (8 D, 5 E) and 1/20 (5 %) deteriorated (D→C). All patients were ambulatory and 19/20 were continent on discharge, with one patient being discharged home with a long-term urinary catheter. All patients returned back to their own home (n = 14/20, 70 %) or a nursing home (n = 6/20, 35 %).

There were 6/20 (30 %) complications: three major (PE, deep wound infection, implant failure) and three minor (superficial wound infection, incidental durotomy, chest infection). The patient with the deep infection developed skin necrosis and required a lattissimus dorsi flap coverage performed successfully by our plastic surgical colleagues, and the patient with PE was managed with anticoagulation. Thirteen patients are deceased [mean survival 367 days (120–603)] and seven patients are still alive [mean survival 719 days (160–1,719)].

Discussion

Metastatic lesions of the lumbo-sacral junction and sacrum pose a complex problem for the surgical management. Most of our patients were presented with a longer duration of lumbo-sacral pain than neurological deterioration. All our patients underwent urgent surgery to decompress the cauda equina with (out) stabilisation. Post-operatively, 5 (25 %) patients improved one Frankel grade, 1(5 %) improved two grades, 13 (65 %) remained stable and 1 (5 %) patient deteriorated. All complications (6/20, 30 %) were managed successfully. All patients were ambulatory post-operatively and 19/20 continent on discharge.

The clinical presentation of a metastatic spinal cord depends upon the anatomical location of the tumour and whether it invades or compresses neighbouring structures. Although the most common presenting symptom is pain, the most catastrophic outcome is neurological compromise [5, 12]. Further, the slower onset of cauda equina symptoms in this patient cohort (as compared to faster onset with a massive lumbar disc prolapse) might explain the better recovery of bladder function.

The literature identifies tumours in the sacral region as being mostly benign aggressive lesions or low grade malignancies that progress slowly expanding out of the sacral cortex limits [12, 13]. The majority of malignant sacral tumours involve metastatic spread from nearby or distant sites [14]. Tumours secondarily involving the sacrum by local extension are predominantly of neural precursor, connective tissue or supportive tissue origin [15]. Early diagnosis is often difficult because symptoms of bladder, bowel, epigastric and sacral plexus compression become evident late on in the presentation. The history of known primary and general symptoms, such as weight loss, raise the suspicion of a secondary sacral lesion [16]. We found those metastases from RCC and the GI tract to be more common in our series accounting for just over half of all patients, which is interesting, especially as these were more common than breast or prostate metastases. This could however, be due to chance in our small series.

Palliative radiotherapy had been the mainstay of first line intervention for spinal tumours since the late 1960s, and was based on numerous comparison studies which reported similar results in patient outcome following laminectomy or radiotherapy [17, 18]. More recent clinical trials have shown significant pain alleviation (82 %), as well as improvement in ambulatory ability (76 %) and sphincter function (44 %) in a series of patients with metastatic spinal cord compression treated with radiotherapy [18]. However, in cases with osseous instability or acute neurological deterioration, urgent surgical decompression and augmentation of the spine is the preferable treatment [19]. Surgical management of symptomatic spinal metastasis is reported to improve the quality of life, and many authors suggest that neurologic deficit improves after surgery in 50–80 % of patients [20, 21]. In our study, two patients had received radiotherapy prior to surgery, three had adjuvant chemotherapy pre-operatively and half the patients received post-operative adjuvant radiotherapy treatment.

In our study, the complication rate was found to be relatively high (30 %) but acceptable considering the underlying condition and surgery undertaken. This is comparable, if not slightly better than other reports [4, 12]. However, our paper is unique in that it reviews only patients with cauda equina compression as a result of a metastatic tumour in the lumbo-sacral junction or sacrum.

Considering the small number of cases analysed and the different origin of tumours evaluated, statistical analysis cannot be performed. However, our study shows that surgery can be important in restoring and preserving neurological function, maintaining mobility and assisting patients to return to their previous residence. Furthermore, given the good survival rate in our series (approximately 1 year in the deceased group and almost 2 years in those who are still alive), we believe surgery to be very beneficial.

References

Kollender Y, Meller I, Bickets J et al (2003) Role of adjuvant cryosurgery in intralesional treatment of sacral tumors. Cancer 97:2830–2838

Cummings BJ, Hobson DI, Bush RS (1983) Chordoma: the results of megavoltage radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 9:633–642

Raque GH Jr, Vitaz TW, Shields CB (2001) Treatment of neoplastic diseases of the sacrum. J Surg Oncol 76:301–307

Wuisman P, Lieshout O, Sugihara S, Van Dijk M (2000) Total sacrectomy and reconstruction: oncologic and functional outcome. Clin Orthop 381:192–203

Llauger J, Palmer J, Amores S, Bague S, Camins A (2000) Primary tumors of the Sacrum :diagnostic imaging. Am Roentgenol 174:417–424

Quraishi NA, Gokaslan ZL, Boriani S (2010) The surgical management of metastatic epidural compression of the spinal cord. J Bone Joint Surg Br 92(8):1054–1060

Quraishi NA, Esler C (2011) Metastatic spinal cord compression. British Med J 342:d2402

Quraishi NA, Giannoulis KE, Edwards KL, Boszczyk BM (2012) Management of metastatic sacral tumours. Eur Spine J 21(10):1984–1993

King GJ, Kostuik JP, McBroom RJ, Richardson W (1991) Surgical management of metastatic renal carcinoma of the spine. Spine 16:265–271

Sundaresan N, Choi IS, Hughes JEO, Sachdev VP, Berenstein A (1990) Treatment of spinal metastases from kidney cancer by presurgical embolization and resection. J Neurosurg 73(4):548–554

Berkefeld J, Scale D, Kirchner J, Heinrich T, Kollath J (1999) Hypervascular spinal tumors: influence of the embolization technique on perioperative hemorrhage. AJNR 20(5):757–763

Feiz-Erfan I, Fox BD, Nader R, Suki D, Chakrabarti I, Mendel E, Gokaslan ZL, Rao G, Rhines LD (2012) Surgical treatment of sacral metastases: indications and results. J Neurosurg Spine 17(4):285–291

Hingibotham NL, Philips RF, Farr HW et al (1967) Chordoma thirty-five year study at Memorial Hospital. Cancer 20:1841–1850

Kollender Y, Bickets J, Price WM et al (2000) Metastatic renal cell carcinoma of bone: indications and technique of surgical intervention. J Urol 164:1505–1508

Gibbs IC, Chang SD (2003) Radiosurgery and Radiotherapy for Sacral Tumours. Neurosurg Focus 15(2):E8

Salehi SA, McCafferty RR, Karahalios D et al (2002) Neural function preservation and early mobilization after resection of metastatic sacral tumours and Lumbosacropelvic junction reconstruction Report of three cases. J Neurosurgery 97(Spine 1):88–93

Marshall LF, Langift TW (1997) Combined treatment for metastatic extradural tumours of the spine. Cancer 40:2067–2070

Maranzano E, Latini P (1995) Effectiveness of radiation therapy with out surgery in metastatic spinal cord compression : final results from a prospective trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 32:959–967

Loblaw DA, Laparriere NJ (1998) Emergency treatment of malignant extradural spinal cord compression : an evidenced based guideline. J Clin Oncol 16(4):1613–1624

Sundaresan N, Scher H, DiGiacinto GV, Yagoda A, Whitmore W, Choi IS (1986) Surgical treatment of spinal cord compression in kidney cancer. J Clin Oncol 4:1851–1856

Weigl B, Maghsudi M, Neuman C, Kretschmer R, Muller FL, Nhrlich M (1999) Surgical management of symptomatic spinal metastasis. Spine 24:2240–2246

Conflict of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Quraishi, N.A., Giannoulis, K.E., Manoharan, S.R. et al. Surgical treatment of cauda equina compression as a result of metastatic tumours of the lumbo-sacral junction and sacrum. Eur Spine J 22 (Suppl 1), 33–37 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-012-2615-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-012-2615-2