Abstract

The aim of this study involving 170 patients suffering from non-specific low back pain was to test the validity of the spinal function sort (SFS) in a European rehabilitation setting. The SFS, a picture-based questionnaire, assesses perceived functional ability of work tasks involving the spine. All measurements were taken by a blinded research assistant; work status was assessed with questionnaires. Our study demonstrated a high internal consistency shown by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.98, reasonable evidence for unidimensionality, spearman correlations of >0.6 with work activities, and discriminating power for work status at 3 and 12 months by ROC curve analysis (area under curve = 0.760 (95% CI 0.689–0.822), respectively, 0.801 (95% CI 0.731–0.859). The standardised response mean within the two treatment groups was 0.18 and −0.31. As a result, we conclude that the perceived functional ability for work tasks can be validly assessed with the SFS in a European rehabilitation setting in patients with non-specific low back pain, and is predictive for future work status.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Low back pain (LBP) continues to be a major health problem in developed countries causing sickness absence and the need for disability pensions [1]. Only a few patients with back pain have pathoanatomically well-defined diseases. Known causes for specific back pain are vertebral fracture, tumour, infection, inflammatory diseases, nerve root compression, spondylolisthesis, spinal stenosis and definite instability [2]. Evidence suggests that fewer than 15% of individuals with back pain can be assigned to one of these specific back pain categories [3]. Chronic LBP disability is mostly attributed to non-specific low back pain (NSLBP) [2, 4] and depends often on psychosocial factors [4]. The assessment of patients with LBP should include diagnostic triage to exclude specific spinal pathology as well as the assessment of work-related factors, psychosocial distress, patient expectations, and extreme symptom reporting [5]. Modern treatment guidelines for NSLBP define return to work as the primary rehabilitation goal [5, 6].

Perceived self-efficacy is a relevant psychosocial factor contributing to the outcome in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain [7]. According to Bandura [8], perceived self-efficacy affects how people behave in difficult situations, and people who doubt their capabilities shy away from tasks which they view as personal threats. Patients with back pain tend to have experienced difficulties with manual material handling [9], which may affect their perceived functional ability. The assessment of perceived functional ability for work-related activities in patients with NSLBP plays an important role in their management, and is proposed to be a predictor for return to work [10].

The use of self-reported measures to assess perceived functional ability is limited by literacy level [11] and depends on linguistic abilities. Text-based questionnaires are often impossible to administer in European rehabilitation settings for the treatment of patients with different mother tongues. A possible approach to overcome this problem is the use of picture-based questionnaires such as the spinal function sort (SFS) [10]. The SFS has shown a high practicability in rehabilitation settings where patients from pan-European origin are treated, and is recommended for work-related rehabilitation [12].

The clinical utility of the SFS has so far only been reported in patient samples from the USA [13, 14]. The reliability and validity of the SFS were investigated in English-speaking patients with back pain from the United States [10] and Australia [15] reporting good psychometric properties of the SFS. No studies have been performed investigating the validity of the SFS in European patients.

Purpose of this study

The aim of this study was to test the validity of the SFS by assessing internal consistency, unidimensionality, concurrent and predictive validity, and responsiveness in a European rehabilitation setting for patients with NSLBP.

Method

Study design, data collection, and subjects

This validation study is embedded within a randomised controlled trial investigating the effectiveness of a function-centred treatment when compared with a pain-centred treatment with 3 and 12 months of follow-up for working status. Eligible were patients with non-acute NSLBP, between 20 and 55 years of age, presenting with at least 6 weeks of sick leave during the previous 6 months, who were referred to the Rehabilitationsklinik Valens (Switzerland) for inpatient rehabilitation [16, 17]. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Canton of St. Gallen, Switzerland (EKSG 03/035).

Measurements

All measurements were taken by a blinded research assistant at entry and discharge of the patients for rehabilitation. Work status at 3 and 12 months of follow-up was assessed with a questionnaire sent to employers and the patients’ primary physicians, who were blinded to the patients’ group assignments. Patients were classified as returned to work if they worked at least 1 day in the follow-up period.

Spinal function sort

The SFS assesses perceived ability to perform work tasks that involve the spine in various ways. It was developed in the United States by Matheson et al. [18] and consists of 50 graphically depicted tasks with simple descriptions. The patient is instructed to look at each drawing and rate each task on a separate evaluation sheet on a 5-point scale from “able” to “restricted” to “unable”. The SFS is scored by the assessor and yields a single rating of perceived functional ability ranging from 0 to 200. The scores were categorised according to the work demands as defined by the dictionary of occupational titles (DOT), thereby allowing a comparison with perceived functional ability and work [10]. Patients with an SFS score of <100 are categorised as having minimal working capacity (see Table 1).

Body functions

Back strength was assessed with the Biering-Sorensen test, measuring the amount of time a patient can maintain a prone position, the unsupported upper body horizontally with the lower body strapped to the treatment table [19]. Back-related range of motion was measured with a finger to floor distance in centimetres, and straight leg raise tests in degrees against a horizontal line with a bubble inclinometer.

Work-related activity

A functional capacity evaluation (FCE) as described by Isernhagen [20] was performed. FCE is a standardised battery of clinical tests that intend to measure a patient’s safe physical ability for work-related activity. For the purpose of this study, five lifting tests were performed assessing the maximum safe ability to handle weight from “Floor to Waist”, “Waist to Overhead”, “Horizontal”, and “Single Handed Carry” (right and left).

Personal beliefs

Pain intensity was measured with numeric rating scale. The Fear Avoidance Belief Questionnaire (FABQ) was used to assess how patients were affected by fear and avoidance beliefs. The questionnaire provides a score for fear of physical activity ranging from 0 (no fear) to 24 (maximum fear) and one for work activities ranging from 0 to 42 [21]. Translated versions of the FABQ were available in German, Italian, Serbo-Croatian, Albanian, Turkish, French, Spanish, and Portuguese.

Data analyses

Internal consistency at entry and discharge

Internal consistency was assessed by item-total correlations and Cronbach’s alpha. For a scale to be sufficiently reliable for the use in groups of patients, an alpha value of 0.80 is considered acceptable [22].

Unidimensionality

Principal component analysis of all 50 items of the discharge SFS score was used to assess the unidimensionality of the instrument. An eigenvalue criterion of 1.0 was used for the factor analysis. Ratios of first to second eigenvalues of 3:1 are generally considered evidence for unidimensionality [23].

Concurrent validity at entry to discharge

Concurrent validity was assessed by comparing the entry and discharge SFS scores with body function, work-related activity, and personal beliefs with Spearman’s correlation coefficient. We hypothesised that the SFS scores would correlate highly to personal beliefs and work-related activity (i.e. r > 0.60) and moderately to body function (0.30–0.60).

Predictive validity for work status

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was used [24] to evaluate the diagnostic performance of the SFS scores at discharge for work status at 3 and 12 months of follow-up. The diagnostic properties of the proposed SFS score ranges related to the DOT categories [10] were assessed by calculating sensitivity and specificity as well as positive and negative predictive value. Within the context of work-related rehabilitation of patients with back pain, the aim is to identify those patients with a probability of not returning to work. Therefore, sensitivity refers to the proportion of patients who had not returned to work and were correctly identified by the DOT category. Another interesting aspect for clinicians is the positive predictive value of the perceived work capability for not returning to work. This was calculated as the percentage of the patients within a DOT category who had not returned to work. According to the definition of the DOT category, we hypothesised that a perception of a minimal working capacity (SFS score <100) would have a high positive predictive value identifying those patients who would not return to work at 3 and 12 months of follow-up.

Responsiveness from entry to discharge

Because the function-centred treatment was specially targeted towards improving perceived ability, it was hypothesised that these patients would have a greater improvement in SFS than the patients in the pain-centred treatment group. Responsiveness was, therefore, assessed in the two treatment groups separately, with the standardised response mean which was calculated by dividing the mean change scores by the standard deviation of the change scores.

Data were analysed using SPSS for windows version 11.5. The ROC curve analysis was performed with MedCalc version 9.7.3.0. Bonferroni’s procedures were applied to reduce type I error in the assessment of concurrent validity. Adjustment for 12 comparisons at alpha = 0.05 resulted in the use of p < 0.005 as level of significance.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Subjects

170 of the 174 subjects who participated in the randomised controlled trial fully completed the SFS at discharge, and were included in this study. The subjects’ characteristics are described in Table 2.

Internal consistency at entry and discharge

A high internal consistency at entry and discharge shown by a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.98 was found. Corrected total item correlation was at entry in two items below 0.30 and at discharge in three items below 0.30 and one item 0.32. All of these items asked for a very high physical capacity handling weights of 50 kg. Mean scores were in these four items above 4.9 with low standard deviations of 0.3 showing high agreement amongst subjects that they were unable to perform such heavy tasks. Alpha would not have been substantially changed if these items had been removed. The remaining 46 items all showed a total item correlation of >0.6.

Unidimensionality

Inspection of the correlation matrix revealed the presence of the majority of coefficients of >0.3. Principal component analysis revealed the presence of seven components with eigenvalues exceeding 1, explaining 55.6, 8.0, 4.3, 2.8, 2.5, 2.2, and 2.1% of the variance, respectively. An inspection of the screeplot revealed a break at two components. To aid the interpretation of these components, a Varimax rotation was performed. The rotation solution revealed the presence of a mixed structure with two components showing a number of strong loadings. Variables 45–48 loaded on different components. The two-factor solution explained a total of 63.6% of the variance, with component 1 contributing 46.0% of the variance and component 2 contributing 17.6%. Ratio from first to second eigenvalue was 6.95, suggesting reasonable evidence for unidimensionality.

Concurrent validity at entry and discharge

Complete measurements and SFS total scores at entry and discharge were available from 156 patients. Correlations were higher at discharge as compared to entry. Correlations between SFS and work activities were high (>0.6) except for manual handling from waist to crown. Back strength and pain intensity also showed high correlation with the SFS total score at discharge. Fear and avoidance beliefs for work activities showed markedly higher correlation with the SFS score than fear and avoidance beliefs for physical activities (see Table 3).

Predictive validity of SFS at discharge for work status at 3 and 12 months of follow-up

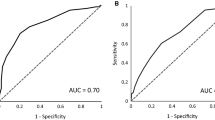

Work status at the 3-month follow-up was known in all patients. 66 returned to work and 104 did not. At the 12-month follow-up, work status was known in 163 patients of which 75 returned to work and 88 did not. Area under the ROC curve was 0.760 (95% CI 0.689–0.822) for work status at 3-month follow-up (see Fig. 1) and 0.801 (95% CI 0.731–0.859) at 12-month follow-up (see Fig. 2). The difference in the area under the ROC curve at 3 and 12 months of follow-up was not statistically significant.

Seventy-six patients judged their working capacity as minimal, achieving an SFS score of <100. 62 of these patients were not at work at 3 months and 59 were not at work at 12 months of follow-up (see Table 4). The positive predictive value of a score of <100 was 81.6 for work status at 3-month follow-up and 79.9 at 12-month follow-up, respectively. The 15 patients who were falsely positively diagnosed as not returning to work had an SFS score between 28 and 96. None of the patients with an SFS score of ≤28 (n = 7) returned ever to work, resulting in a positive predictive value of 100 for both times of follow-up.

Responsiveness

Patients in the function-centred treatment group (n = 84) showed at discharge an increase in perceived self-efficacy with a mean change score of 5.9 (SD 32.5) resulting in a standardised response mean of 0.18, while the patients in the pain-centred treatment group (n = 85) showed a decrease in perceived self-efficacy with a mean change score of −7.4 (SD 24.4) resulting in a standardised response mean of −0.31 [16].

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study assessing the validity of the SFS in a European rehabilitation setting. The high follow-up rate of work status at 3 and 12 months allowed a thorough evaluation of the diagnostic accuracy of the SFS for work status. We found discriminating power of the proposed SFS-transformed DOT categories for work status. High DOT categories have a high sensitivity in diagnosing patients not returning to work, but an unacceptably high rate of false-positive findings. The proposed SFS cut-off score of 100 indicating minimal working capacity results in a high probability for not returning to work at 3 and 12 months of follow-up. Considering the specificity of 78.7, respectively, 80.0 and the high prevalence of patients with NSLBP not returning to work, both factors being determinants of the positive predictive value, we can recommend using an SFS score of ≤100 for screening purposes in clinical practice identifying patients with high probability of not returning to work.

The validation study of this picture-based questionnaire included patients from 10 different nations. We found higher correlations of perceived functional ability with all measurements at discharge and interpreted this as the effect of repeated testing, giving the patients a more accurate perception of their functional ability. Four out of the five comparisons of SFS scores with FCE tests showed high correlations. Interestingly, these were higher than those of other self-reported measures of low back disability as found by Reneman et al. [25]. Relations of the SFS score with the FABQ activity score were lower than with FABQ work score. These findings add further validity to this questionnaire assessing specifically perceived ability to perform work tasks. Owing to the lower correlations of the FABQ physical activity score than of the FABQ work score, we thought the patients had understood the questions and we, consequently, interpreted the findings as valid, despite the use of non cross cultural adapted translations of the FABQ.

The SFS was able to capture the expected changes in self-perceived ability in the two treatment groups. In contrast to the expectations, the standardised response mean was smaller for the function-centred treatment than the pain-centred treatment. A possible explanation is that the information provided in the pain-centred treatment group, namely to stop activities if pain was provoked, was more powerful than the positive reinforcement provided within the function-centred treatment [16].

Factor analysis has shown reasonable evidence for unidimensionality of the SFS. However, four items asking for manual handling capacity of 50 kg had higher loading for another dimension. These four questions also showed low corrected total item correlation in the assessment of internal consistency. Therefore, we recommend further research using RASCH analysis to investigate unidimensionality and consequently reduce questionnaire items. Owing to the multidimensionality of factors predicting work status in patients with NSLBP, we also recommend further research to assess the contribution of physical functioning, the patient’s perceived functional ability, and other psychosocial work-related factors for work status.

Conclusion

Perceived functional ability for work-related tasks can validly be assessed with the SFS in a European rehabilitation setting treating patients with NSLBP, and is predictive for future work status.

References

Woolf AD, Pfleger B (2003) Burden of major musculoskeletal conditions. Bull World Health Organ 81:646–656

Fordyce W (1995) Back pain in the workplace: management of disability in nonspecific conditions: task force on pain in the workplace. IASP Press, Seattle

Frymoyer JW, Cats-Baril WL (1991) An overview of the incidences and costs of low back pain. Orthop Clin North Am 22:263–271

Waddell G (1998) The back pain revolution. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh

COST B (2006) European guidelines for the management of acute nonspecific low back pain in primary care. Eur Spine J 15(Suppl 2):S125–S300

Abenhaim L, Rossignol M, Valat JP, Nordin M, Avouac B, Blotman F, Charlot J, Dreiser RL, Legrand E, Rozenberg S, Vautravers P (2000) The role of activity in the therapeutic management of back pain. Report of the International Paris Task Force on Back Pain. Spine 25:1S–33S

Rahman A, Reed E, Underwood M, Shipley M, Omar R (2008) Factors affecting self-efficacy and pain intensity in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain seen in a specialist rheumatology pain clinic. Rheumatology 47:1803–1808

Bandura A (1994) Self-efficacy. In: Ramachaudran V (ed) Encyclopedia of human behavior. Academic Press, New York, pp 71–88

Hoogendoorn WE, van Poppel MN, Bongers PM, Koes BW, Bouter LM (1999) Physical load during work and leisure time as risk factors for back pain. Scand J Work Environ Health 25:387–403

Matheson L, Matheson M, Grant N (1993) Development of a measure of perceived functional ability. J Occup Rehabil 3:15–30

Adams J (2009) Literacy levels required to complete the patients reported functional outcomes measures in rheumatology. Ann Rheum Dis 68:771

Oliveri M (2004) Arbeitsbezogene funktionelle Leistungsfähigkeit (Evaluation der funktionellen Leistungsfähigkeit EFL). In: Hildebrandt J, Müller G, Pfingsten M (eds) Lendenwirbelsäule Ursachen, Diagnostik und Therapie von Rückenschmerzen. Urban & Fischer, München, pp 220–235

Sufka A, Hauger B, Trenary M, Bishop B, Hagen A, Lozon R, Martens B (1998) Centralization of low back pain and perceived functional outcome. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 27:205–212

Robinson RC, Kishino N, Matheson L, Woods S, Hoffman K, Unterberg J, Pearson C, Adams L, Gatchel RJ (2003) Improvement in postoperative and nonoperative spinal patients on a self-report measure of disability: the spinal function sort (SFS). J Occup Rehabil 13:107–113

Gibson L, Strong J (2002) Expert review of an approach to functional capacity evaluation. Work 19:231–242

Kool JP, Oesch PR, Bachmann S, Knuesel O, Dierkes JG, Russo M, de Bie RA, van den Brandt PA (2005) Increasing days at work using function-centered rehabilitation in nonacute nonspecific low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 86:857–864

Kool J, Bachmann S, Oesch P, Knuesel O, Ambergen T, de Bie R, van den Brandt P (2007) Function-centered rehabilitation increases work days in patients with nonacute nonspecific low back pain: 1-year results from a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 88:1089–1094

Matheson LN, Matheson M (1989) Spinal function sort, rating of perceived capacity. Performance Assessment and Capacity Testing PACT. Performance Assessment and Capacity Testing PACT, Trabuco Canyon, California

Biering-Sorensen F (1984) Physical measurements as risk indicators for low-back trouble over a one-year period. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 9:106–119

Isernhagen S (1995) Contemporary issues in functional capacity evaluation. In: Isernhagen S (ed) The comprehensive guide to work injury management. Aspen Publishers, Gaithersburg, pp 410–429

Waddell G, Newton M, Henderson I, Somerville D, Main CJ (1993) A fear-avoidance beliefs questionnaire (FABQ) and the role of fear-avoidance beliefs in chronic low back pain and disability. Pain 52:157–168

Bryman A (2004) Social research methods. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Polit D, Beck C (2008) Developing and testing self-report scales. In: Polit D, Beck C (eds) Nursing research, generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice. Lippincott, Philadelphia, pp 474–505

Zweig M, Campbell G (1993) Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) plots: a fundamental evaluation tool in clinical medicine. Clin Chem 39:561–577

Reneman MF, Jorritsma W, Schellekens JM, Goeken LN (2002) Concurrent validity of questionnaire and performance-based disability measurements in patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain. J Occup Rehabil 12:119–129

Acknowledgments

The randomised controlled trial was supported by the Swiss Federal Office of Health (Grant no. 00.00437). We thank Patricia Bigger, who performed the postal follow-up measurements persistently and with admirable patience, and Ariane Knüsel for her assistance in preparing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Oesch, P.R., Hilfiker, R., Kool, J.P. et al. Perceived functional ability assessed with the spinal function sort: is it valid for European rehabilitation settings in patients with non-specific non-acute low back pain?. Eur Spine J 19, 1527–1533 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-010-1429-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-010-1429-3