Abstract

Main Problem: The purpose of this study was to validate the psychometric properties of the functional rating index (FRI), establish the instrument’s minimum clinically important difference (MCID), and compare its psychometric properties with the Oswestry questionnaire. Methods: This was a cohort study of patients with low back pain (LBP) undergoing physical therapy. One thirty one patients with a primary complaint of LBP participating in a clinical trial were assessed at baseline and at a 1- and 4-week follow-up. Test-re-test reliability was examined using the intraclass correlation coefficient, and validity was examined by determining the association between the FRI and Oswestry, a concurrent measure of disability. Responsiveness was examined by calculating the standard error of the measure, minimum detectable change, area under a receiver operating characteristic curve, and minimum clinically important difference. Changes in clinical status at each follow-up period were compared to the average of the patient and therapist’s perceived improvement using the 15-point global rating of change scale. Results: Test-retest reliability of the FRI was moderate, with an intraclass correlation coefficient equal to 0.63 (0.35, 0.80). Validity of the FRI was supported by a moderate correlation between the FRI and Oswestry (r=0.67, P<0.001). Area under the curve for the FRI was 0.93 (0.89, 0.98), and the minimum clinically important difference was approximately nine points. Conclusions: The FRI is less reliable than the Oswestry but appears to have comparable validity and responsiveness. Before the FRI can be recommended for widespread use in patients with neck and low back pain, it should be further tested in patients with neck pain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Next to the common cold, low back pain is the most common reason individuals visit a physician’s office [1] and 54% of individuals have experienced neck pain within the last six months [2]. Given the high prevalence of low back and neck pain, it is important that practitioners and researchers be able to utilize self-report measures with adequate psychometric properties to assess outcome from rehabilitation and to determine the effectiveness of interventions in clinical trials. The Oswestry [3] questionnaire for patients with low back pain (LBP) and neck disability index for patients with neck pain [4] are region-specific health-related quality of life measures commonly used in research and clinical practice for patients with spinal disorders. However, many patients complain of both neck and low back pain, requiring patients to complete multiple instruments for a single episode of care. The functional rating index (FRI) is a self-report measure developed to overcome this limitation by merging similar constructs from the Oswestry and neck disability index into a single instrument, thus for use in patients with neck and/or LBP [5]. Of the ten items included on the FRI, nine represent domains covered in the Oswestry and/or neck disability index. Seven items are represented in the neck disability index, and eight are represented in the Oswestry. An additional item related to the frequency of pain was added based on its ability to predict recovery musculoskeletal conditions [5].

Preliminary findings suggest that psychometric properties of the FRI are sufficient for use in patients with spinal disorders [5]. However, few studies have been done to validate these findings [6]. Furthermore, the instrument’s minimum clinically important difference (MCID) has not been determined. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to validate the psychometric properties of the in patients with LBP, establish the instrument’s minimum clinically important difference, and compare its psychometric properties with the Oswestry questionnaire.

Materials and methods

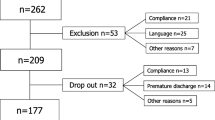

Patients were participants in a multicenter randomized clinical trial of physical therapy interventions. Patients with a primary complaint of LBP with or without lower extremity symptoms, age between 18 and 60 years, and a minimum score of 30% on the Oswestry disability questionnaire were invited to participate. Patients were required to have at least a baseline Oswestry score of 30% to minimize the potential for a floor effect to occur, which was a requirement for the design of the clinical trial [7]. Patients with a history of cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, spinal fracture, osteoporosis, and positive neurologic signs (i.e, positive straight leg raise or altered reflexes, sensation, or strength) were excluded. The study was approved by each site’s Institutional Review Board, and all the patients provided consent prior to participation. The 131 patients reported here represent the total enrollment in the clinical trial. A total of 13 physical therapists at eight clinics located in a variety of healthcare settings and geographical regions throughout the United States participated. The number of subjects treated by each therapist ranged from 1 to 32, with a mean of 10.1 (SD 9.7). The mean number of patients seen at each site ranged from 3 to 34, with a mean of 16.4 (SD 11). The mean response rate on the FRI ranged from 80%–100%, with a mean of 95% (SD 7%). No differences in a response rate were observed between sites (P=0.375).

A baseline examination was performed for all patients, during which disability was assessed using the FRI [5] and the modified Oswestry, a concurrent measure of disability [8]. Lower scores for both instruments represent less disability. Previous research has demonstrated the modified Oswestry as having high levels of reliability, validity and responsiveness and is a widely-used region-specific self-report measure for patients with LBP [8], thus suitable for comparison purposes. Patients enrolled in the study were randomly assigned to receive either a combination of manipulation and a lumbar stabilization exercise program or a lumbar stabilization exercise program alone. Outcome measures were repeated both at one and four weeks after the beginning of treatment. No significant differences in response rates existed between the sites.

At each of the follow-up examinations, patients and the treating therapist were asked to rate the overall change in the patient’s status since the beginning of the physical therapy treatment using a 15-point rating scale described by Jaeschke et al. [9]. The global rating of change ranges from −7 (“a very great deal worse”) to 0 (“about the same”) to +7 (“a very great deal better”). Intermittent descriptors of worsening or improving are assigned values from −1 to −7 and from +1 to +7, respectively. Therapists and patients were blinded to each others’ ratings. Ratings of the therapist and patient were averaged to balance the input of the therapist and patient [8], with the correlation between the therapist and patient ratings equal to 0.85. Patients with an average rating of +3 (“somewhat better”) or greater were considered to have improved. Patients with an average rating of +2 (“a little bit better”) to −2 (“a little bit worse”) were considered to have remained stable. Patients with an average rating of −3 (“somewhat worse”) or smaller were considered to have worsened. The global rating of change has been well validated and extensively used in research as an outcome measure and as an external reference standard to compare outcome measures [10, 11].

Data Analysis

Test-re-test reliability of the FRI was examined using the intraclass correlation coefficient, formula 2, 1 [12] among the subgroup of patients (n=41) whose condition remained stable at the one-week follow-up based on the average patient and therapist global rating. Validity of the FRI was examined by calculating the association between the FRI and the Oswestry scores at baseline using the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient. Responsiveness of the FRI was first characterized by calculating the statistically meaningful change [13] based on the FRI’s standard error of measure and test-retest reliability [14, 15]. Although no consensus exists as to how much change must occur to confidently exceed the bounds of measurement error, previous researchers have reported one standard error of measure as the best measure of meaningful change on health-related quality of life measures [16]. We used 1.96* standard error of measure to calculate the statistically meaningful change, which represents the statistical amount of change necessary to confidently exceed measurement error. Responsiveness was further characterized by calculating the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, which can be used as a quantitative method for assessing a scale’s ability to distinguish patients who have improved from those who have not based on the global rating of change [17–19]. (Fig.1). The MCID was determined based on the 4 week follow-up to be the magnitude of change associated with the uppermost left-hand corner of the curve, where both sensitivity and 1-specificity are maximized [8]. These procedures were repeated using the Oswestry scores for comparison purposes. We have also characterized the responsiveness for the FRI and Oswestry by calculating the standardized effect size at 1- and 4-week follow-up among the patients judged to have improved using the previously defined cutoffs on the average global rating of change. It was calculated as the mean change score divided by the standard deviation of the baseline score for the improve patients. This ratio captures the amount of change in the instrument relative to the random fluctuation in baseline scores[20].

Results

Descriptive characteristics for the entire sample of patients (n=131) are reported in Table 1. Test-re-test reliability of the FRI was moderate, with an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) equal to 0.63 (0.35, 0.80). The ICC for the Oswestry was 0.78 (0.62, 0.88). The validity was supported by a moderate correlation coefficient between the FRI and Oswestry (r=0.67, P<0.001). The area under the curve for the FRI was 0.93 (0.89, 0.98), which was similar to that demonstrated by the Oswestry, with an area under the curve of 0.93 (0.88, 0.98). An MCID of 8.4 points was established for the FRI compared with an MCID of nine points for the Oswestry. Table 2 demonstrates that mean improvements on the FRI and Oswestry exceeded the MCID for each instrument at both the 1- and 4-week follow-up, suggesting that patients generally experienced clinically meaningful change in response to rehabilitation. With an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.63 and a common standard deviation of 12.3 points, the standard error of measure for the FRI was 7.5 points. Thus the statistically meaningful change for the FRI was 15 points (1.96 * 7.5). With an intraclass correlation coefficient 0.78 and a common standard deviation of 13.9 points, the standard error of measure for the Oswestry was 6.5 points. The statistically meaningful change for the Oswestry was therefore 12.8 points (1.96*6.5). The values of the standardized effect sizes for the two instruments are reported in Table 2.

Discussion

The FRI offers several advantages for clinicians. First, although we did not record the time necessary to complete the FRI in this study, previous work that reported the average time necessary to complete and score the instrument was only 78 s, attesting to its clinical utility [5]. Reducing the administrative burden of having patients complete separate region-specific self-report measures is especially beneficial for patients with complaints of both neck and low back pain. Unlike outcome measures specific to the neck or low back, the FRI can also be used to compare relative magnitudes of disability between these regions.

Despite these advantages, it has been suggested that because most spine research focuses on one region of the spine, the value of the FRI for researchers is less clear [21]. Researchers are more concerned about a measure’s psychometric properties than its clinical utility and will be reluctant to abandon widely-used self-report measures such as the Oswestry and neck disability index unless comparable psychometric properties can be demonstrated. The results of this study demonstrate that although slightly less reliable, the FRI appears to be sufficiently valid, demonstrated by the strong correlation of the FRI with the Oswestry. Similar areas under the curve for the FRI and Oswestry suggest that the FRI is equally effective in distinguishing between patients who have improved and those who have not.

Although region-specific measures are used in research to make comparisons between groups, it is also helpful to have information that can improve decision-making for individual patients. Therefore, clinicians must have a sense for how much change is necessary before the change is considered meaningful. Meaningful change can be considered from both a statistical and clinical perspective [22]. From a statistical perspective, calculation based on the measurement error is used to determine the amount of change needed to be certain, within an established level of confidence, that “true change” has occurred [23]. The statistically meaningful change for the FRI was based on the standard error of measure. The disadvantage of this perspective is that it fails to consider the clinical importance of the change.

The MCID overcomes this limitation in that it is patient-centered, representing the amount of change in a measure that needs to be observed before the change can be considered clinically meaningful [22]. A patient’s level of improvement on a self-report measure can then be examined in the context of the MCID for a particular instrument to determine whether a clinically meaningful change has occurred. This was the first study to characterize the MCID for the FRI. The MCID of approximately nine points for both the FRI and Oswestry again suggest similar levels of responsiveness. However, previous studies demonstrated the MCID on the Oswestry to be lower than in our study. One study reported an MCID of size points [8], whereas another reported a MCID between four and size points [24], suggesting the Oswestry may be slightly more responsive. Our study supports similar responsiveness of the FRI and Oswestry. Values of nine points in the MCID for both instruments and statistically meaningful change of 15 points for the FRI and 13 points for the Oswestry were very similar.

Some may question how to interpret our finding that the MCID is smaller than the statistically meaningful change. However, some researchers have speculated that the MCID may be less than the minimum level of statistical change [16, 25, 26]. One reason why the MCID was lower than the statistically meaningful change in this study may be attributable to the relatively lower ICC of the patients whose clinical status remained stable, resulting in a larger SEM. Two reports have indicated that a 1-SEM criterion best approximated the MCID using the Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [13, 16], The authors suggested that the 1-SEM criterion may be an accurate estimate of the MCID. This was the case in our study since the MCID value was closer to 1-SEM than 1.96*SEM.

One of the limitations of this study is that the Oswestry may not be the ideal reference standard because the FRI was in part derived from this instrument. Future studies could further examine the validity of the FRI using a more general measure of function and disability such as the Physical Function Subscale of SF-36. Because patients were required to have a minimum level of disability on the Oswestry of 30%, our findings may not be generalizable to patients with lower levels of disability. Finally, future research needs to validate the psychometric properties of the FRI in patients with neck pain using a variety of statistical and clinically meaningful methods. In the light of these considerations, combined with the FRI’s lower reliability, future research is necessary before the FRI can be recommended for widespread use.

Conclusion

The FRI is less reliable than the Oswestry but appears to have comparable validity and responsiveness. Before the FRI can be recommended for widespread use in patients with neck and low back pain, it should be further tested in patients with neck pain.

Disclaimer

The opinions or assertions contained herein are the private views of the author (JDC) and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the U.S. Air Force or Department of Defense.

References

Deyo RA, Phillips WR (1996) Low back pain. A primary care challenge. Spine 21:2826–2832

Cote P, Cassidy JD, Carroll L (2000) The factors associated with neck pain and its related disability in the Saskatchewan population. Spine 25:1109–1117

Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB (2000) The Oswestry Disability Index. Spine 25:2940–2953

Vernon H, Mior S (1991) The neck disability index: a study of reliability and validity. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 14:409–415

Feise RJ, Michael MJ (2001) Functional rating index: a new valid and reliable instrument to measure the magnitude of clinical change in spinal conditions. Spine 26:78–86

Bayar B, Bayar K, Yakut E, Yakut Y (2004) Reliability and validity of the Functional Rating Index in older people with low back pain: preliminary report. Aging Clin Exp Res 16:49–52

Childs JD, Fritz JM, Flynn TW, Irrgang JJ, Delitto A, Johnson KK, Majkowski GR (2004) Validation of a clinical prediction rule to identify patients likely to benefit from spinal manipulation: a randomized clinical trial. Ann Intern Med (in Press)

Fritz JM, Irrgang JJ (2001) A comparison of a modified oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire and the quebec back pain disability scale. Phys Ther 81:776–788

Jaeschke R, Singer J, Guyatt GH (1989) Measurement of health status. Ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Control Clin Trials 10:407–415

Goldsmith CH, Boers M, Bombardier C, Tugwell P (1993) Criteria for clinically important changes in outcomes: development scoring and evaluation of rheumatoid arthritis patient and trial profiles. OMERACT Committee. J Rheumatol 20:561–565

Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Willan A, Griffith LE (1994) Determining a minimal important change in a disease-specific quality of life questionnaire. J Clin Epidemiol 47:81–87

Shrout PE, Fleiss JL (1979) Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull 86:420–428

Wyrwich KW, TierneyWM, Wolinsky FD (1999) Further evidence supporting an SEM-based criterion for identifying meaningful intra-individual changes in health-related quality of life. J Clin Epidemiol 52:861–873

Eliasziw M, Young SL, Woodbury MG, Fryday-Field K (1994) Statistical methodology for the concurrent assessment of interrater and intrarater reliability: using goniometric measurements as an example. Phys Ther 74:777–788

Roebroeck ME, Harlaar J, Lankhorst GJ (1993) The application of generalizability theory to reliability assessment: an illustration using isometric force measurements. Phys Ther 73:386–395

Wyrwich KW, Nienaber NA, Tierney WM, Wolinsky FD (1999) Linking clinical relevance and statistical significance in evaluating intra-individual changes in health-related quality of life. Med Care 37:469–478

Altman DG, Machin D, Bryant TN, Gardner MJ (2000) Statistics with confidence 2nd edn. British Medical Journal Bristol

Deyo RA, Centor RM (1986) Assessing the responsiveness of functional scales to clinical change: an analogy to diagnostic test performance. J Chronic Dis 39:897–906

Kopec JA, Esdaile JM (1995) Functional disability scales for back pain. Spine 20:1943–1949

Stratford PW, Binkley FM, Riddle DL (1996) Health status measures: strategies and analytic methods for assessing change scores. Phys Ther 76:1109–1123

Cherkin D (2001) Point of view: functional rating index: a new valid and reliable instrument to measure the magnitude of clinical change in spinal conditions. Spine 26:87

Wells G, Beaton D, Shea B, Boers M, Simon L, Strand V, Brooks P, Tugwell P (2001) Minimal clinically important differences: review of methods. J Rheumatol 28:406–412

Stratford PW, Binkley JM, Riddle DL, Guyatt GH (1998) Sensitivity to change of the Roland-Morris Back Pain Questionnaire: part 1. Phys Ther 78:1186–1196

Beurskens AJ, de Vet HC, Koke AJ (1996) Responsiveness of functional status in low back pain: a comparison of different instruments. Pain 65:71–76

Stratford PW, Finch E, Solomon P (1996) Using the Roland-Morris Questionnaire to make decisions about individual patients. Physiother Can 48:107–110

Stratford PW, Binkley J, Solomon P, Finch E, Gill C, Moreland J (1996) Defining the minimum level of detectable change for the Roland-Morris questionnaire. Phys Ther 76:359–365

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the physical therapy staff at the following sites for their assistance with data collection: (1) Wilford Hall Medical Center, Lackland Air Force Base (AFB); (2) Malcolm Grow Medical Center, Andrews AFB; (3) Wright-Patterson Medical Center, Wright-Patterson AFB; (4) Eglin Hospital, Eglin AFB; (5) Luke Medical Clinic, Luke AFB; (6) Hill Medical Clinic, Hill AFB; (7) F.E. Warren Medical Clinic, F.E. Warren AFB; and (8) University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Health System’s Centers for Rehab Services. This study was supported by a grant from the Foundation for Physical Therapy, Inc. and the Wilford Hall Medical Center Commander’s Intramural Research Funding Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

An erratum to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00586-005-1038-8

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Childs, M.J.D., Piva, S.R. Psychometric properties of the functional rating index in patients with low back pain. Eur Spine J 14, 1008–1012 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-005-0900-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-005-0900-z