Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to examine the association between body mass index and chronic pain.

Methods

The outcome was chronic pain prevalence by body mass index (BMI). BMIs of less than 18.5, 18.5–25.0, 25.0–30.0, and 30.0 or over kg/m2 were defined as underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese.

Subjects

We used data from 4993 participants (2464 men and 2529 women aged 20–79 years) of the Pain Associated Cross-sectional Epidemiological survey in Japan. Sex-stratified multivariable-adjusted odds ratios were calculated with 95% confidence intervals using a logistic regression model including age, smoking, exercise, sleep time, monthly household expenditure, and presence of severe depression. We analyzed all ages and age subgroups, 20–49 and 50–79 years.

Results

The prevalence of chronic pain was higher among underweight, overweight, and obese male respondents than those reporting normal weight, with multivariable odds ratios of 1.52 (1.03–2.25), 1.55 (1.26–1.91), and 1.71 (1.12–2.60). According to underweight, only older men showed higher prevalence of chronic pain than normal weight men with odd ratios, 2.19 (1.14–4.20). Being overweight and obese were also associated with chronic pain in women; multivariable odds ratios were 1.48 (1.14–1.93) and 2.09 (1.20–3.64). Being underweight was not associated with chronic pain.

Conclusion

There was a U-shaped association between BMI and chronic pain prevalence among men ≥ 50 years, and a dose–response association among women. Our finding suggests that underweight should be considered in older men suffering chronic pain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The association between obesity and chronic pain has been well-documented by researchers [1]. We have the clinical impression, however, that underweight people are also more likely to report chronic pain. People with severe chronic pain may lose their appetite for food and, therefore, lose weight. Few studies, however, have examined whether being underweight is correlated with chronic pain. This study, therefore, sought to investigate this issue.

Body mass index (BMI), calculated using the square of the height in meters (kg/m2), is a simple index designed to consider health risks by body proportions [2]. The current WHO classification defines underweight as having a BMI of less than 18.50 kg/m2 [2]. The proportion of underweight people in Japan (4.4% of men and 11.0% of women aged 20 and over in 2009) is higher than other developed countries [3]. For example, the proportion of underweight adults was 1.0% of men and 2.6% of women aged 20 and over in the United States in 2009–2010 [4], and 2.2% of men and 2.5% of women aged 16 and over in the United Kingdom in 2009 [5]. Being underweight can sometimes signal a life-threatening condition medically. Some underlying diseases such as cancer, cardiac failure, and infectious diseases, might have cause underweight. Although far, fewer people are underweight than overweight or obese in developed countries, this does not mean being underweight should be ignored. For example, an association between being underweight and increasing all-cause mortality has previously been reported [6]. It is, therefore, important to examine the association between being underweight and chronic pain as well as to reinvestigate the association between being overweight or obese and chronic pain among Japanese people.

Methods

Study population

The Pain Associated Cross-sectional Epidemiological (PACE) study was a web-based survey designed to investigate pain in a large Japanese population using a self-reported questionnaire. It was conducted from 10 to 18 January 2009. The profiles of the PACE study participants have been reported previously [7, 8]. The aim of this study was completely different from the previous PACE-related studies, which examined the association between work-related psychosocial factors, childhood adversity, and chronic pain [8, 9]. A total of 20,044 respondents (9746 men and 10,298 women) aged 20–79 years, and matching the Japanese demographic composition in 2007, were recruited by e-mail from 1477,585 candidates who registered with the web-based survey company (Rakuten Research Inc., Tokyo, Japan) (see Fig. 1) [10]. Candidates were sent invitational e-mails with a link to the first questionnaire, and invitations were sent until the targeted sample number was achieved. Incomplete questionnaires were rejected automatically, so the response rate could not be calculated. The first questionnaire included items on age, sex, and pain, and was completed by 20,044 respondents. The second round of questionnaires, about lifestyle and psychosocial factors, was sent to 5000 of these respondents, chosen to be consistent with the Japanese demographic composition for sex and age in 2007 [10]. Half of these 5000 respondents were chosen from those who had reported being without pain in the first questionnaire, and the other half had reported pain. We excluded seven respondents (two men and five women) who reported with pain from cancer, because we wished to focus on non-cancer-related chronic pain. Data on 4993 individuals (2464 men and 2529 women) aged 20–79 were, therefore, included in the analyses.

Definitions and measures

Pain

The first questionnaire included a question about whether the respondents were in pain or not. If they were, they answered about the location of their pain and its intensity at each site, the site and duration of the dominant pain, and the main episodes that evoked pain. The nine options of episodes that evoked pain were described in the questionnaire; spontaneous, accident at work, working motion or posture, during commuting, daily motion or posture, traffic accident, in sports, disease, and others. Pain intensities were scored on an 11-point Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) (0 = no pain, 10 = worst pain imaginable).

Chronic pain

We defined ‘chronic pain’ as pain over a period of 3 months, in line with the definition of the International Association for the Study of Pain [11].

Severe depressive symptoms

The Mental Health Inventory (MHI-5), which is identical to the ‘Mental Health’ domain of the 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36), was used to evaluate mental health status. The MHI-5 includes five items, each rated on a six-point scale ranging from 1 to 6. The five items were summed to give a total score ranging from 5 to 30 points, which was then converted to a 100-point scale. The cut point of < 52 on the MHI-5 (corresponding to ≥ 56 on the 20-item Zung Self-rating Depression Scale, ZSDS) was useful for screening severe depressive symptoms with sensitivity of 91.8% and specificity of 84.6% in a previous Japanese study, so we used a cut-off point of < 52 to define severe depression [12].

Statistical analysis

We used Dunnett’s method to test for differences in mean values and proportions of risk factors for chronic pain by BMI category. We examined the association between BMI category (less than 18.5 kg/m2, from 18.5 up to 25.0, from 25.0 up to 30.0, and 30.0 or over) and the prevalence of chronic pain. We calculated sex-stratified multivariable-adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) using a logistic regression model, because the sex difference in chronic pain pathogenesis was reported in the previous study [13]. To examine the influence of age, we stratified respondents into two age groups: younger, aged 20–49 years and older, aged 50–79 years.

Adjusted variables were age, smoking status (never, ex-smoker, or current smoker), exercise (exercise longer than 30 min more than twice a week: yes or no), sleep duration (an average over the last month; hours/day), household expenditure (JPY/month), and presence of severe depressive symptoms (MHI-5 < 52). Those adjusted variables were considered as confounding factors or risks of chronic pain from the previous studies [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23].

p values of < 0.05 for two-tailed tests were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Ethical provisions

A credit point for Internet shopping was given to the respondents as an incentive. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. The institutional review boards of The University of Tokyo (No. 1264) and Japan Labour Health and Welfare Organization (No. 452) approved the study. All participants gave their informed consent before responding to the questionnaire.

Results

Of the 4993 respondents (2464 men and 2529 women) aged 20–79 in this study, 1723 (815 men and 908 women) (34.5%) reported chronic pain. Table 1 shows chronic pain characteristics. Table 2 shows the mean values or proportions of characteristics by BMI category. Underweight and obese men were younger (42.7 and 42.9 vs. 47.7 years), and overweight men were older (49.8 vs. 47.7 years) than normal weight men. Overweight men were more likely to sleep for fewer than 6 h each night than normal weight men (20.2 vs. 15.2%). A greater proportion of underweight men showed severe depressive symptoms compared with normal weight men (30.0 vs. 20.8%). Fewer underweight and obese men (25.8 and 19.6%) had an exercise routine than their normal weight peers (37.2%).

Underweight women were younger (43.8 vs. 49.0 years), taller (157.5 vs. 156.5 cm), and more likely to be current smokers (19.9 vs. 14.3%) than normal weight women. They were also more likely to have severe depressive symptoms (33.1 vs. 21.0%).

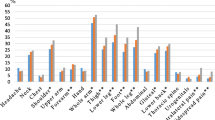

The multivariable-adjusted ORs for chronic pain prevalence (Table 3; Fig. 2) were 1.52 (95% CI 1.03–2.25, p < 0.05) for underweight men, 1.55 (1.26–1.91, p < 0.001) for overweight men, 1.71 (1.12–2.60, p < 0.05) for obese men, 1.48 (1.14–1.93, p < 0.01) for overweight women, and 2.09 (1.20–3.64, p < 0.01) for obese women. No associations were observed between being underweight and chronic pain among women. Table 4 and Fig. 2 show the multivariable-adjusted ORs for chronic pain prevalence by BMI category, stratified into two age groups: younger and older. The association between underweight and chronic pain was only observed among older men, where the multivariable-adjusted OR was 2.19 (1.14–4.20, p < 0.05). Younger underweight men also had slightly more chronic pain, but this was not statistically significant (OR 1.23, 95% CI 0.74–2.03, p > 0.05). There was no association between being underweight and chronic pain prevalence among younger or older women.

Overweight and obese younger men were more likely to have chronic pain, with ORs of 1.51 (1.11–2.06, p < 0.01) and 1.70 (1.02–2.83, p < 0.05). Older overweight men were also more likely to have chronic pain, with multivariable-adjusted OR of 1.55 (1.17–2.07, p < 0.01). Obese and overweight younger women had an increased risk of chronic pain, although those associations were not statistically significant. Overweight and obese older women were more likely to have chronic pain, with multivariable ORs of 1.52 (1.06–2.17, p < 0.05) and 2.98 (1.07–8.31, p < 0.05).

Discussion

Our main finding was that there was a U-shaped association between BMI and chronic pain prevalence among older men and a dose–response association among women, regardless of age (Fig. 2). The association between being overweight or obese and the prevalence of chronic pain is consistent with the previous studies [1].

Previous studies suggested that the association between being overweight or, obese and chronic pain could be a result of mechanical stress or a chemical mediator [1]. Heavy loads on joints and the spine may lead to chronic musculoskeletal pain among obese people [24, 25]. Suffering from the eating disorder bulimia as a result of obesity may be linked to a central nervous disorder and severe chronic pain. Both eating disorders and chronic pain are associated with disorders of the reward system in the brain [26, 27], as well as with systemic inflammation [28].

There are several reasons why being underweight might be associated with chronic pain among older men. Being underweight as a result of muscle weakness from inactivity or aging burdens the intervertebral disks and joints, and causes chronic musculoskeletal pain, which is also mediated by systemic inflammation [29]. Those with chronic pain may also lose their appetite and, therefore, lose weight. In that case, removing the persistent pain would also prevent them from being underweight [30].

It has also recently been pointed out that the mechanism behind being underweight (e.g., systemic inflammation or eating disorder due to central nervous abnormality) partially overlaps with that for being overweight and obese, both pathologically and psychologically [26,27,28, 31]. Systemic inflammation may be common mechanism between underweight, overweight, and obese in this study. Although neuroimaging showed that patients with anorexia nervosa had hyper sensitivity in the orbitofrontal cortex and the insula which are key regions of the brain reward system which is known as a reason chronic pain [27], prevalence of anorexia nervosa are higher among young women than older men, so anorexia nervosa may not explain the association between underweight and chronic pain prevalence in the current study [32].

In contrast to men, being underweight was not associated with chronic pain in women. The reason for this discrepancy is unclear, but one potential reason may be misclassification. In this study, women may have underreported their weight, since Japanese women generally wish to be thin [33]. The proportion of underweight women in this study was higher and that of overweight/obese women in this study was lower than in a national statistical report of actually measured weight in women aged 20 years or older in 2009 (underweight, 14.1 vs. 11.0%, overweight, 11.0 vs. 17.3%, and obese, 2.2 vs. 3.5%) [7]. The proportion of underweight, overweight, and obese men, in contrast, was almost identical to that in the national statistical report (underweight, 4.9 vs. 4.4%, overweight, 20.9 vs. 26.1%, and obese, 4.1 vs. 4.3%) [3]. Many normal weight women were, therefore, likely to be included in the underweight group in our study, so the effect of being underweight on the prevalence of chronic pain could have been underestimated.

This study had several limitations. First, the respondents may not be truly representative of the general population in Japan. The internet survey has a number of sampling issue, as described previously [34]. People without internet access could not participate in this research. Second, a self-administered questionnaire was used to measure body weight and height. According to a previous prospective population-based study among Japanese people aged 40–59 years at baseline, self-reported BMIs were slightly lower but almost equivalent to the actual measured values, and the Spearman correlation coefficient was approximately 0.9 in both sexes [35]. However, these results were derived from middle-aged people, so misclassification of BMI in the underweight category may have occurred among younger and older people. Third, the study was cross-sectional and cannot show the direction of causality. Finally, respondents with chronic pain as a result of severe diseases other than cancer may lose weight.

In conclusion, being underweight was associated with chronic pain among men ≥ 50 years. This result suggests that being underweight should be considered when treating those with chronic pain.

References

Okifuji A, Hare B. The association between chronic pain and obesity. J. Pain Res. 2015;8:399. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4508090&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. Accessed 29 Nov 2017.

Whorld Health Organization. BMI classification: global database on body mass index. 2004.http://apps.who.int/bmi/index.jsp?introPage=intro_3.html.Accessed 6 Sep 2012.

The Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare. National Health and Nutrition Survey 2009 (in Japanese). 2009. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/kenkou/eiyou/dl/h21-houkoku-08.pdf. Accessed 16 Sep 2012.

National Center for Health Statistics. Prevalence of underweight among adults aged 20 and over: United States, 1960–1962 through 2013–2014. Centers Dis. Control Prev. 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/underweight_adult_13_14/underweight_adult_13_14.htm. Accessed 16 Sep 2012.

National Obesity Observatory. Adult weight: NOO data briefing. 2011. http://www.noo.org.uk/uploads/doc/vid_11515_Adult_Weight_Data_Briefing.pdf. Accessed 16 Sep 2012.

Berrington de Gonzalez A, Hartge P, Cerhan JR, Flint AJ, Hannan L, MacInnis RJ, Moore SC, Tobias GS, Anton-Culver H, Freeman LB, Beeson WL, Clipp SL, English DR, Folsom AR, Freedman DM, Giles G, Hakansson N, Henderson KD, Hoffman-Bolton J, Hoppin JA, Koenig KL, Lee IM, Linet MS, Park Y, Pocobelli G, Schatzkin A, Sesso HD, Weiderpass E, Willcox BJ, Wolk A, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, Willett WC, Thun MJ. Body-mass index and mortality among 1.46 million white adults. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2211–9. http://www.nejm.org/doi/abs/10.1056/NEJMoa1000367. Accessed 29 Nov 2017.

Yamada K, Matsudaira K, Takeshita K, Oka H, Hara N, Takagi Y. Prevalence of low back pain as the primary pain site and factors associated with low health-related quality of life in a large Japanese population: a pain-associated cross-sectional epidemiological survey. Mod Rheumatol. 2014;24:343–8.

Yamada K, Matsudaira K, Imano H, Kitamura A, Iso H. Influence of work-related psychosocial factors on the prevalence of chronic pain and quality of life in patients with chronic pain. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010356.

Yamada K, Matsudaira K, Tanaka E, Oka H, Katsuhira J, Iso H. Sex-specific impact of early-life adversity on chronic pain: a large population-based study in Japan. J Pain Res. 2017;10:427–33.

Japanese Ministry of Internal Affirs and Communications. The Japanese demographic composition in 2007. 2007. http://www.stat.go.jp/data/jinsui/2007np/index.htm. Accessed 14 Mar 2015.

Treede RD, Rief W, Barke A, Aziz Q, Bennett MI, Benoliel R, Cohen M, Evers S, Finnerup NB, First MB, Giamberardino MA, Kaasa S, Kosek E, Lavandʼhomme P, Nicholas M, Perrot S, Scholz J, Schug S, Smith BH, Svensson P, Vlaeyen JW, Wang SJ. A classification of chronic pain for ICD-11. Pain. 2015;156:1003–7.

Yamazaki S, Fukuhara S, Green J. Usefulness of five-item and three-item Mental Health Inventories to screen for depressive symptoms in the general population of Japan. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3:48.

Craft RM, Mogil JS, Maria Aloisi A. Sex differences in pain and analgesia: the role of gonadal hormones. Eur J Pain. 2004;8:397–411.

Inoue S, Kobayashi F, Nishihara M, Arai YC, Ikemoto T, Kawai T, Inoue M, Hasegawa T, Ushida T. Chronic pain in the Japanese community-prevalence, characteristics and impact on quality of life. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0129262.

Ditre JW, Brandon TH, Zale EL, Meagher MM. Pain, nicotine, and smoking: research findings and mechanistic considerations. Psychol Bull. 2011;137:1065–93.

Ruotsalainen H, Kyngäs H, Tammelin T, Kääriäinen M. Systematic review of physical activity and exercise interventions on body mass indices, subsequent physical activity and psychological symptoms in overweight and obese adolescents. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71:2461–77.

Generaal E, Vogelzangs N, Penninx BWJH, Dekker J. Insomnia, sleep duration, depressive symptoms, and the onset of chronic multisite musculoskeletal pain. Sleep. 2017;40(1):zsw030. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsw030.

Fishbain DA, Cutler R, Rosomoff HL, Rosomoff RS. Chronic pain-associated depression: antecedent or consequence of chronic pain? A review. Clin J Pain. 1997;13:116–37.

Nixon JP, Mavanji V, Butterick TA, Billington CJ, Kotz CM, Teske JA. Sleep disorders, obesity, and aging: the role of orexin. Ageing Res Rev. 2015;20:63–73.

Tian J, Venn A, Otahal P, Gall S. The association between quitting smoking and weight gain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Obes Rev. 2015;16:883–901.

Magee L, Hale L. Longitudinal associations between sleep duration and subsequent weight gain: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2012;16:231–41.

Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF, Stijnen T, Cuijpers P, Penninx BW, Zitman FG. Overweight, obesity, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:220–9.

Dinsa GD, Goryakin Y, Fumagalli E, Suhrcke M. Obesity and socioeconomic status in developing countries: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2012;13:1067–79.

Alexiou GA, Voulgaris S. Body mass index and lumbar disc degeneration. Pain Med. 2013;14:313.

Samartzis D, Karppinen J, Chan D, Luk KDK, Cheung KMC. The association of lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration on magnetic resonance imaging with body mass index in overweight and obese adults: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:1488–96.

Kenny PJ. Reward mechanisms in obesity: new insights and future directions. Neuron. 2011;69:664–79.

Frank GKW. Advances from neuroimaging studies in eating disorders. CNS Spectr. 2015;20:1–10.

Visser M, Bouter LM, McQuillan GM, Wener MH, Harris TB. Elevated C-reactive protein levels in overweight and obese adults. JAMA. 1999;282:2131–5.

Teichtahl AJ, Urquhart DM, Wang Y, Wluka AE, O'Sullivan R, Jones G, Cicuttini FM. Physical inactivity is associated with narrower lumbar intervertebral discs, high fat content of paraspinal muscles and low back pain and disability. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:114.

Bosley BN, Weiner DK, Rudy TE, Granieri E. Is chronic nonmalignant pain associated with decreased appetite in older adults? Preliminary evidence. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:247–51.

Bano G, Trevisan C, Carraro S, Solmi M, Luchini C, Stubbs B, Manzato E, Sergi G, Veronese N. Inflammation and sarcopenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas. 2017;96:10–5.

Lähteenmäki S, Saarni S, Suokas J, Saarni S, Perälä J, Lönnqvist J, Suvisaari J. Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders among young adults in Finland. Nord J Psychiatry. 2014;68:196–203.

Mori N, Asakura K, Sasaki S. Differential dietary habits among 570 young underweight Japanese women with and without a desire for thinness: a comparison with normal weight counterparts. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2016;25:97–107.

Rhodes SD, Bowie DA, Hergenrather KC. Collecting behavioural data using the world wide web: considerations for researchers. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57:68–73.

Tsugane S, Sasaki S, Tsubono Y. Under- and overweight impact on mortality among middle-aged Japanese men and women: a 10-y follow-up of JPHC study cohort I. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2012;26:529–37.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Yasuo Takagi, professor of Keio University, Japan, for his valuable help in conducting the survey. We thank Melissa Leffler, MBA, from Edanz Group for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

About this article

Cite this article

Yamada, K., Kubota, Y., Iso, H. et al. Association of body mass index with chronic pain prevalence: a large population-based cross-sectional study in Japan. J Anesth 32, 360–367 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00540-018-2486-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00540-018-2486-8