Abstract

Background

We previously reported that eradication of Helicobacter pylori in our cohort of patients with peptic ulcer disease reduced their risk of developing gastric cancer to approximately one–third after a mean follow-up period of 3.4 years (up to 8.6 years). We have now followed these patients for a longer period.

Methods

A total of 1,222 consecutive patients with peptic ulcer diseases who completed more than 1-year follow-up after receiving H. pylori eradication therapy were followed with annual endoscopic surveillance for a mean of 9.9 years (as long as 17.4 years).

Results

H. pylori infection was judged cured in 1,030 patients (eradication-success group) but persisted in 192 (eradication-failure group) after initial eradication therapy. In the eradication-failure group, 114 patients received re-treatment at a mean of 4.4 years after the start of follow-up, and 105 of these were cured of infection. Gastric cancer developed in 21 of the 1,030 patients in the eradication-success group and in nine of the 192 in the failure group (p = 0.04). The risk of developing gastric cancer in the eradication-success group (0.21 %/year) was significantly lower than that in the failure group (0.45 %, p = 0.049). The longest interval between the initial H. pylori eradication and the occurrence of gastric cancer was 14.5 years in the eradication-success group and 13.7 years in the eradication-failure group.

Conclusions

A prophylactic effect for gastric cancer persists for more than 10 years after H. pylori eradication therapy, but we should be aware that cancer can develop even after that interval.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori is a causative bacterium for gastric cancer [1, 2]. The possible prophylactic effect of H. pylori eradication on the development of gastric cancer is important and being evaluated. A randomized controlled study in Japan showed that eradication therapy reduced the risk of developing metachronous gastric cancer after endoscopic mucosal resection of early gastric cancer [3]. However, in people with H. pylori infection in whom the cancer is not yet established, a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials failed to show a significant prophylactic effect of eradication therapy [4, 5]. Recently, analysis of extended follow-up of the original randomized controlled trial [6], which was included in the meta-analysis, revealed a significant reduction of gastric cancer incidence 14.7 years after the eradication therapy [7].

We have been following a cohort of patients who had received H. pylori eradication therapy and have reported outcomes of several important medical issues in these patients [8–14]. We showed that the eradication of H. pylori in patients with peptic ulcer disease reduced their risk of developing gastric cancer to approximately one-third after a follow-up period as long as 8.6 years (mean, 3.4 years) [10]. We have now followed our cohort for as long as 17.4 years, and herein report their incidence of gastric cancer.

Patients and methods

We enrolled 1,342 consecutive patients (152 women and 1,190 men, a mean age of 50 years, range, 17–83 years) with peptic ulcer disease who had received H. pylori eradication therapy in the outpatient clinic of Nippon Kokan Fukuyama Hospital from June 1995 to March 2003. The patients were mostly male factory workers at JFE Steel Corporation, West Japan Works. The patients underwent endoscopic examination at enrollment to evaluate peptic ulcer, background gastric mucosal histology including grade of atrophy, and H. pylori infection; we documented that none of the patients had gastric cancer. A total of 776 patients had gastric ulcer; 495 had duodenal ulcer, and 71 had both. Gastric mucosal atrophy was evaluated according to the endoscopic-atrophic-border scale described by Kimura and Takemoto [15, 16], which correlates with the results of histological evaluation [17, 18]. Atrophy was classified according to three grades of severity: mild (C-1 and C-2 patterns), moderate (C-3 and O-1 patterns), or severe (O-2 and O-3 patterns). We excluded patients who had previously undergone gastrectomy or received endoscopic therapy (endoscopic mucosal resection or endoscopic submucosal dissection) for gastric neoplasms (early gastric cancer or gastric adenoma); those who were pregnant; those who were allergic to penicillin, clarithromycin, or metronidazole; those who were taking anticoagulants; and those who had used a proton pump inhibitor, H2 receptor antagonist, adrenocortical steroids, or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs within the month preceding the eradication therapy.

Eradication therapy and post-eradication schedule

H. pylori infection was defined as a positive bacterial culture from endoscopic biopsy specimens taken before eradication therapy was started. The specimens were obtained from the greater curvature of the body and the antrum of the stomach, and cultured using Brucella agar with 7 % horse blood and antibiotics. Urease activity of the specimens was tested with a modified rapid urease test (MR UREA S; Institute of Immunology Co., Tokyo, Japan). Patients received H. pylori eradication therapy as described [10]. Treatment regimens consisted of a proton-pump inhibitor together with amoxicillin or with two of the following three drugs: amoxicillin, clarithromycin, or metronidazole. One to two months after completion of therapy, including the cessation of maintenance therapy with acid secretion inhibitors, a 13C-urea breath test and endoscopy were carried out in each patient to determine H. pylori status and to determine again if gastric cancer had developed. H. pylori infection was considered cured when the bacterial culture, rapid urease test, and urea breath test (cut-off value, 3.5 per mil) [19] all were negative. Thereafter, endoscopy (throughout the follow-up period) and urea breath test (until March 2008) were carried out yearly. Patients who were judged at the first evaluation to have had unsuccessful eradication or patients who were judged to have had successful eradication but had positive urea breath tests or bacterial culture during follow-up evaluation received additional eradication therapy when they wished. Gastric cancer was classified according to Lauren as intestinal or diffuse type [20]. The biopsy specimens obtained from the greater curvature of the body and the antrum of the stomach were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and the degree of inflammatory cell infiltration was classified according to the updated Sydney system [21]. The pathologists were not aware of the clinical data, including patients’ H. pylori status.

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. A local ethics committee approved the study protocol. The objective of the study was explained to all patients before their participation, and written informed consent was obtained from each of them.

Statistical analysis

Statistical differences were calculated using the Mann–Whitney U test, the χ 2 test, and Fisher’s exact test. Survival curves were constructed with the Kaplan–Meier method, and statistically significant differences between curves were tested with the log-rank test. Factors associated with a preventive effect against gastric cancer were assessed with Cox’s proportional-hazards models.

Results

A flow chart of the follow-up results is presented in Fig. 1. Among the 1,342 patients, 1,135 were cured of infection, and 207 had persistent infection at the time of the first evaluation of H. pylori. One hundred five of the patients who were cured of infection and 15 with persistent infection were dropped from the study because they failed to complete the 1-year follow-up. A total of 1,222 patients (135 women and 1,087 men, with a mean age of 50 years) completed more than 1-year follow-up and were followed up for as long as 17.4 years (mean, 9.9 years) after receiving the initial eradication therapy. Among them, H. pylori infection was judged cured in 1,030 (eradication-success group) and persisted in 192 patients (eradication-failure group) at the initial evaluation. The patients’ demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. There was no significant difference between the eradication-success group and the eradication-failure group with respect to gender, alcohol consumption, location of peptic ulcers, and background gastric mucosal atrophy. In the eradication-failure group, mean age was less (p = 0.03), smokers were more frequent (p = 0.04), and the duration of follow-up was longer (10.4 vs. 9.8 years, p = 0.01) than in the eradication-success group.

Follow-up flow chart. Of the 1,342 patients originally enrolled, 120 dropped out and 1,222 completed more than 1-year follow-up and were followed for up to 17.4 years (mean, 9.9 years) after receiving the initial eradication therapy. H. pylori infection was judged cured in 1,030 (eradication-success group) and persisted in 192 patients (eradication-failure group) at the initial evaluation. Gastric cancer developed in 21 of the 1,030 patients in the eradication-success group and nine in total of the 192 in the failure group (p = 0.04, Fisher’s exact test). Asterisk indicates 23 were cured of infection; 22 with additional therapy, one with further additional therapies, and two were not cured of infection. Dagger indicates 94 patients were cured of infection by single additional therapy (one patient had a repeat positive urea breath test, suggesting possible re-infection with H. pylori after the additional therapy; his infection was cured after another course of therapy), ten required the additional therapy twice, and one required it four times

When it became evident that eradication of H. pylori had a significant preventive effect on gastric cancer (as we reported in Ref. [10]), we recommended re-treatment for patients in the eradication-failure group. One hundred fourteen patients received re-treatment 4.4 ± 3.9 (mean ± standard deviation) years after the start of follow-up. One hundred five of them were cured of infection, 94 by a single additional treatment, ten by two additional treatments, and one by four additional treatments. H. pylori infection was not cured in the other nine patients; thus H. pylori infection persisted in a total of 87 patients in the eradication-failure group throughout the follow-up period. In the eradication-success group, urea breath tests or bacterial culture were positive in 25 patients 5.5 ± 3.7 years after the start of follow-up, and all these patients received additional therapy. Twenty-three of them were cured of infection, 22 by a single additional treatment and one by two additional treatments; two were not cured of infection (Fig. 1).

Gastric cancer developed in 30 of the 1,222 patients; 21 were among the 1,030 patients in the eradication-success group and nine among the 192 in the eradication-failure group (p = 0.04, Fisher’s exact test) (Fig. 1; Table 1). In three of the nine patients in the eradication-failure group, gastric cancer developed after cure of infection by additional treatments. Most gastric cancers were in early TNM stages (stage 0 or IA, n = 26; stage IB, n = 2; stage IIB, n = 1; and stage IIIA, n = 1). Histologically, 11 of the gastric cancers were the diffuse-type or mixed-type, and 19 were the intestinal-type. Ten of the 11 diffuse-type or mixed-type gastric cancers developed in the eradication-success group, and one in the eradication-failure group. Eleven of the 19 intestinal-type gastric cancers developed in the eradication-success group, and eight in the eradication-failure group (p = 0.10, Fisher’s exact test).

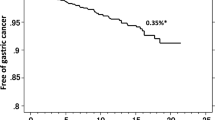

By Kaplan–Meier analysis, the risk of developing gastric cancer among patients in the eradication-success group (0.21 %/year) was significantly lower than among patients in the eradication-failure group (0.45 %, p = 0.049, log-rank test) (Fig. 2). The longest interval between the initial H. pylori eradication therapy and the occurrence of gastric cancer was 14.5 years in patients of the eradication-success group and 13.7 years in those of the eradication-failure group (Fig. 2).

Kaplan–Meier analysis of the proportion of patients in the eradication-success group and patients in the eradication-failure group who remained free of gastric cancer. The risk of developing gastric cancer among patients in the eradication-success group (0.21 %/year) was significantly lower than in patients in the eradication-failure group (0.45 %/year, p = 0.049, log-rank test). The longest intervals between the initial H. pylori eradication and the occurrence of gastric cancer were 14.5 years in the patients in the eradication-success group and 13.7 years in those in the failure group

When we compared the gastric cancer incidence between groups based on their final H. pylori status during the follow-up period, the gastric cancer incidence was 0.21 %/year in the patients cured of infection (n = 1133) and 0.74 %/year in the patients with persistent infection (n = 89; 87 from the eradication-failure group and two from the eradication-success group who became re-positive for H. pylori during follow-up) by Kaplan–Meier analysis (p = 0.003, log-rank test) (Fig. 3).

Kaplan–Meier analysis of the proportion of patients cured of infection and patients with persistent infection at the final assessment who remained free of gastric cancer. When we compared the gastric cancer incidence between groups based on their final H. pylori status during the follow-up period, the gastric cancer incidence was 0.21 %/year in patients cured of infection (n = 1,133) and significantly lower than in patients with persistent infection (n = 89) (0.74 %/year, p = 0.003, log-rank test)

Analysis with the Cox’s proportional-hazards model identified three significant factors for the prophylactic effect of eradication therapy against gastric cancer: successful result at the initial treatment (hazard ratio, 0.4; 95 % confidence interval, 0.2–0.9, p = 0.03); younger age (per 10-years decline) (0.6; 0.4–0.9, p = 0.02); and mild baseline gastric mucosal atrophy: mild (0.2; 0.1–0.7 vs. severe, p = 0.01) (Table 2).

Discussion

In the present study with extended follow-up, we confirmed our previous findings [10, 11] that H. pylori eradication reduced the risk of developing gastric cancer in patients with peptic ulcer disease. In addition, we showed that the prophylactic effect for gastric cancer persisted for more than 10 years after the cure of H. pylori infection.

Analysis with the Cox’s proportional-hazards model identified successful initial treatment as a significant factor for the prophylactic effect against gastric cancer. As shown in the follow-up flow chart (Fig. 1), approximately two-thirds of patients in the eradication-failure group received additional treatment, and most of them achieved cure of infection. Still, the incidence of gastric cancer in the patients in the eradication-success group, defined by the result at initial treatment, was significantly lower than that in the patients in the eradication-failure group. When we analyzed the gastric cancer incidence according to the final H. pylori status, the prophylactic effect of curing H. pylori infection against gastric cancer was more impressive.

In the eradication-failure group, gastric cancer developed in three patients cured of infection by additional treatments. Additional treatment in initial treatment-failure patients was carried out a mean of 4.5 years after the initial treatment. Ideally, the treatment would have been given sooner because early eradication may be important in achieving a more protective effect against gastric cancer. As we found in our previous studies [11, 13], in this study we identified younger age and mild baseline gastric mucosal atrophy as the other significant factors for the prophylactic effect of eradication therapy against gastric cancer. H. pylori infection induces gastritis, leading to atrophic change in the gastric mucosa. The longer H. pylori infection persists, the more severe and extensive the gastric mucosal atrophy becomes. Our findings suggest that eradication of H. pylori is maximally effective in preventing gastric cancer if it is achieved before significant gastric atrophy has developed. Thus, therapy should be prescribed as early as possible, especially in young people, when their gastric mucosal atrophy is still mild. Our findings are in accordance with the report from Taiwan by Wu et al. [22], in which they retrospectively investigated the Taiwan National Health Insurance Database and found that early H. pylori eradication was associated with decreased risk of gastric cancer in patients with peptic ulcer diseases. Our study complemented their study in being a prospective study, with longer-term observation, in a different (Japanese) population.

Another important reason for eradicating H. pylori in the young generation is that of reducing the reservoir for H. pylori infection. H. pylori is transmitted per oral route mainly during early childhood. In Japan, intra-familial transmission, especially mother-to-child transmission, is the predominant route of H. pylori transmission [23]. Eradication of H. pylori in the young generation before they bear children should prevent the transmission of H. pylori to the next generation, and the decline in the population of H. pylori-infected persons will be accelerated. If effective, comprehensive eradication can be accomplished, the entire nation will be populated with people free of H. pylori infection and thus have little or no risk of gastric cancer [2].

In the present study, we showed also that the preventive effect against gastric cancer of H. pylori eradication persisted for more than 10 years. However, it is important to recognize that cure of H. pylori infection did not completely prevent the development of gastric cancer, and that cancer developed in some patients even more than 10 years after the cure of infection. Further studies are needed to clarify how patients who have had H. pylori eradication should be followed, i.e., how often, how long, and by which methods to find gastric cancer at its early stage.

Our study has limitations. First, only Japanese patients were studied, and they were mostly male with peptic ulcer diseases. The results obtained here need extended evaluations with other races, female subjects, and people who are positive for H. pylori but without peptic ulcer diseases. Second, there was a significant difference between the eradication-success group and the eradication-failure group with respect to age, smoking, and the duration of follow-up. We cannot explain the difference. Nevertheless, analysis with these factors included in the Cox’s proportional-hazards model identified successful results at the initial treatment, younger age, and mild baseline gastric mucosal atrophy as the significant and independent factors for the prophylactic effect of eradication therapy against gastric cancer (Table 2). Third, although our study is prospective, it is nonetheless an observational cohort study, so hidden confounders could not be excluded. To raise the level of evidence, randomized control studies are necessary. However, we observed our cohort for as long as 17.4 years (a mean of 9.9 years). To obtain comparable outcomes, more than 10 years of follow-up will be required.

As shown in our study as well as the study of Wu et al. [22], eradication of H. pylori in younger patients and early eradication is most effective in preventing gastric cancer. In addition, the most recent meta-analysis showed that searching for and eradicating H. pylori reduced the incidence of gastric cancer in healthy asymptomatic infected Asian individuals [24]. Thus, H. pylori should be eradicated now [25]. In Japan, if we treat H. pylori-associated gastritis, i.e., H. pylori eradication therapy, especially in young generations, taking advantage of national health insurance coverage of this therapy, deaths from gastric cancer should decrease dramatically after 10–20 years, as stated in a recent review by Asaka et al. [26].

References

Graham DY. Helicobacter pylori infection is the primary cause of gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2000;35(Suppl 12):90–7.

Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, Matsumura N, Yamaguchi S, Yamakido M, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784–9.

Fukase K, Kato M, Kikuchi S, Inoue K, Uemura N, Okamoto S, et al. Effect of eradication of Helicobacter pylori on incidence of metachronous gastric carcinoma after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer: an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:392–7.

Fuccio L, Zagari RM, Eusebi LH, Laterza L, Cennamo V, Ceroni L, et al. Meta-analysis: can Helicobacter pylori eradication treatment reduce the risk for gastric cancer? Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:121–8 Epub 2009/07/22.

Erratum. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:516.

You WC, Brown LM, Zhang L, Li JY, Jin ML, Chang YS, et al. Randomized double-blind factorial trial of three treatments to reduce the prevalence of precancerous gastric lesions. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:974–83 Epub 2006/07/20.

Ma JL, Zhang L, Brown LM, Li JY, Shen L, Pan KF, et al. Fifteen-year effects of Helicobacter pylori, garlic, and vitamin treatments on gastric cancer incidence and mortality. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:488–92 Epub 2012/01/25.

Take S, Mizuno M, Ishiki K, Nagahara Y, Yoshida T, Inaba T, et al. Interleukin-1beta genetic polymorphism influences the effect of cytochrome P 2C19 genotype on the cure rate of 1-week triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2403–8.

Ishiki K, Mizuno M, Take S, Nagahara Y, Yoshida T, Yamamoto K, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication improves pre-existing reflux esophagitis in patients with duodenal ulcer disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:474–9.

Take S, Mizuno M, Ishiki K, Nagahara Y, Yoshida T, Yokota K, et al. The effect of eradicating Helicobacter pylori on the development of gastric cancer in patients with peptic ulcer disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1037–42.

Take S, Mizuno M, Ishiki K, Nagahara Y, Yoshida T, Yokota K, et al. Baseline gastric mucosal atrophy is a risk factor associated with the development of gastric cancer after Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy in patients with peptic ulcer diseases. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42(Suppl 17):21–7.

Take S, Mizuno M, Ishiki K, Nagahara Y, Yoshida T, Yokota K, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication may induce de novo, but transient and mild, reflux esophagitis: prospective endoscopic evaluation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:107–13.

Take S, Mizuno M, Ishiki K, Yoshida T, Ohara N, Yokota K, et al. The long-term risk of gastric cancer after the successful eradication of Helicobacter pylori. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:318–24 (Epub 2010/11/26).

Take S, Mizuno M, Ishiki K, Imada T, Okuno T, Yoshida T, et al. Reinfection rate of Helicobacter pylori after eradication treatment: a long-term prospective study in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:641–6 (Epub 2012/02/22).

Kimura K, Takemoto T. An endoscopic recognition of the atrophic border and its significance in chronic gastritis. Endoscopy. 1969;3:87–97.

Sakaki N, Arakawa T, Katou H, Momma K, Egawa N, Kamisawa T, et al. Relationship between progression of gastric mucosal atrophy and Helicobacter pylori infection: retrospective long-term endoscopic follow-up study. J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:19–23.

Ito S, Azuma T, Murakita H, Hirai M, Miyaji H, Ito Y, et al. Profile of Helicobacter pylori cytotoxin derived from two areas of Japan with different prevalence of atrophic gastritis. Gut. 1996;39:800–6.

Satoh K, Kimura K, Taniguchi Y, Yoshida Y, Kihira K, Takimoto T, et al. Distribution of inflammation and atrophy in the stomach of Helicobacter pylori-positive and -negative patients with chronic gastritis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:963–9.

Nagahara Y, Mizuno M, Maga T, Ishiki K, Okuno T, Yoshida T, et al. Outcome of patients with inconsistent results from 13C-urea breath test and bacterial culture at the time of assessment of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy in Japan. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1700–3.

Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:31–49.

Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney system. International workshop on the histopathology of gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1161–81 Epub 1996/10/01.

Wu CY, Kuo KN, Wu MS, Chen YJ, Wang CB, Lin JT. Early Helicobacter pylori eradication decreases risk of gastric cancer in patients with peptic ulcer disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(1641–8):e1–2 Epub 2009/08/12.

Konno M, Yokota S, Suga T, Takahashi M, Sato K, Fujii N. Predominance of mother-to-child transmission of Helicobacter pylori infection detected by random amplified polymorphic DNA fingerprinting analysis in Japanese families. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:999–1003 Epub 2008/10/11.

Ford AC, Forman D, Hunt RH, Yuan Y, Moayyedi P. Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy to prevent gastric cancer in healthy asymptomatic infected individuals: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2014;348:g3174.

Graham DY, Shiotani A. The time to eradicate gastric cancer is now. Gut. 2005;54:735–8.

Asaka M, Kato M, Sakamoto N. Roadmap to eliminate gastric cancer with Helicobacter pylori eradication and consecutive surveillance in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:1–8.

Acknowledgments

S. Take and M. Mizuno contributed principally and equally to the study. The authors thank to Drs. Tsuyoshi Okamoto, Tomomi, Hakoda, Takayuki Imada, Masako Kataoka, Yoshimi Itoh and Hideaki Inoue (Nippon Kokan Fukuyama Hospital) for support of this work and Dr. William R. Brown (Denver, Colorado) for assistance in preparation of the manuscript. This work was supported in part by Health Labour Sciences Research Grant, The Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare, Tokyo, Japan.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Take, S., Mizuno, M., Ishiki, K. et al. Seventeen-year effects of eradicating Helicobacter pylori on the prevention of gastric cancer in patients with peptic ulcer; a prospective cohort study. J Gastroenterol 50, 638–644 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-014-1004-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-014-1004-5