Abstract

Background

The serine protease inhibitor Kazal type 1 (SPINK1), also known as pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor (PSTI), is a peptide secreted by pancreatic acinar cells. Genetic studies have shown an association between SPINK1 gene variants and chronic pancreatitis or recurrent acute pancreatitis. The aim of this study was to clarify whether the SPINK1 variants affect the level of serum PSTI.

Methods

One hundred sixty-three patients with chronic pancreatitis or recurrent acute pancreatitis and 73 healthy controls were recruited. Serum PSTI concentrations were determined with a commercial radioimmunoassay kit.

Results

Ten patients with the p.N34S variant, 7 with the IVS3+2T>C variant, two with both the p.N34S and the IVS3+2T>C variants, and one with the novel missense p.P45S variant in the SPINK1 gene were identified. The serum PSTI level in patients with no SPINK1 variants was 14.3 ± 9.6 ng/ml (mean ± SD), and that in healthy controls was 10.7 ± 2.2 ng/ml. The PSTI level in patients carrying the IVS3+2T>C variant (5.1 ± 3.4 ng/ml), but not in those with the p.N34S variant (8.9 ± 3.5 ng/ml), was significantly lower than that in the patients without the SPINK1 variants and the healthy controls. The serum PSTI level in the patient with the p.P45S variant was 4.9 ng/ml. Low levels of serum PSTI (<6.0 ng/ml) showed sensitivity of 80 %, specificity of 97 %, and accuracy of 96 % in the differentiation of IVS3+2T>C and p.P45S carriers from non-carriers.

Conclusion

Serum PSTI levels were decreased in patients with the IVS3+2T>C and p.P45S variants of the SPINK1 gene.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Chronic pancreatitis (CP) is a progressive inflammatory disease that eventually leads to impairment of the exocrine and endocrine functions of the organ [1, 2]. It has been suggested that pancreatitis results from an imbalance of proteases and their inhibitors within the pancreatic parenchyma, and recent human genetic studies have supported this concept. Gain-of-function mutations in the cationic trypsinogen (protease, serine, 1; PRSS1) gene are causes of hereditary pancreatitis [3, 4]. Mutations in the serine protease inhibitor Kazal type 1 (SPINK1) gene are thought to diminish protection against prematurely activated trypsin, and are thereby linked to trypsin-related pancreatic injury [5–9]. Loss-of-function alterations in the chymotrypsin C (CTRC) gene, whose product specifically degrades all human trypsin/trypsinogen isoforms, predispose to pancreatitis by diminishing the protective trypsin-degrading activity of this gene [10]. Of these genes, SPINK1, also known as pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor (PSTI), provides the first line of defense against premature trypsinogen activation within the pancreas [11]. Previous studies have shown that variants in the SPINK1 gene are associated with CP of various etiologies including idiopathic, familial, and tropical [5–9, 12]. The p.N34S (c.101A>G) variant has been found worldwide in CP patients and healthy controls, with an average allele frequency of 9.7 and 1 %, respectively [6–9, 13]. We and others have reported that the p.N34S variant is strongly associated with recurrent acute pancreatitis (RAP), but does not increase the risk of the first or sentinel acute pancreatitis event [14, 15]. The second most common haplotype contains the c.-215G>A promoter polymorphism and the IVS3+2T>C (c.194+2T>C) variant which affects the 5′ splicing site in intron 3. This haplotype has been reported in patients with idiopathic, familial, and alcoholic CP [6–8, 16]. Currently, approximately 40 variants in the SPINK1 gene have been reported (http://www.uni-leipzig.de/pancreasmutation).

The serum levels of PSTI increase in association with severe inflammation, tissue destruction, and malignant diseases, including pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer [17–19 and references therein]. On the other hand, decreased levels of serum PSTI have also been reported [20, 21]. Nakano et al. [20] have shown that serum PSTI was decreased in 2 of 26 patients with calcifying CP, but the level was not decreased in any patients with other digestive diseases. Satake et al. [21] found decreased serum PSTI levels (<5.8 ng/ml) in 4 of 23 patients with CP and in 6 of 30 with pancreatic cancer. But the pathophysiological significance of lower PSTI levels has not been fully determined. We previously examined the mRNA sequences of the SPINK1 gene and revealed that the IVS3+2T>C variant caused skipping of the whole of exon 3 [22]. Other functional studies have revealed that several missense variants, such as p.G48E, p.D50E, p.Y54H, p.R65Q, and p.R67C, reduce PSTI secretion by causing intracellular retention and degradation [23, 24]. Accordingly, we hypothesized that the serum PSTI levels would be decreased in patients carrying these SPINK1 variants. The aim of this study was to clarify whether the SPINK1 variants affected the level of serum PSTI.

Methods

Subjects

All enrolled subjects gave their informed consent according to the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tohoku University School of Medicine (article number: 2010-45 and 2010-355; principal investigator: A. Masamune). A total of 114 patients with CP, 49 patients with RAP, and 73 healthy controls were enrolled in this study. The characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. None of the patients or control subjects had developed malignant diseases. We recruited relatively young healthy controls (36.6 ± 9.4 years old).

The diagnosis of CP was based on clinical examinations, laboratory tests, radiological findings of pancreatic calcifications by computed tomography and endoscopic ultrasonography, and/or pathological findings such as pancreatic ductal irregularities and dilatations on endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography [2]. The diagnosis of hereditary pancreatitis was made on the basis of three or more relatives in two or more generations with CP and/or the confirmation of PRSS1 gene mutations. Patients in whom the criteria for hereditary pancreatitis were not met but who had at least 2 affected family members were classified as having familial pancreatitis. Idiopathic CP included patients in whom no predisposing factor was identified. Patients with alcohol consumption of more than 80 g/day for at least 2 years were classified as having alcoholic CP. Autoimmune pancreatitis was diagnosed in patients with characteristic findings such as increased levels of serum γ-globulin or IgG4, the presence of autoantibodies, diffuse enlargement of the pancreas, and diffusely irregular narrowing of the main pancreatic duct. The diagnosis of acute pancreatitis was based on typical clinical features, elevated serum amylase and lipase (three times the upper limit of normal), and positive findings on computed tomography.

Mutational analysis

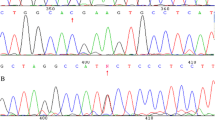

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leucocytes according to the standard protocol. All exons and the promoter region of the SPINK1 gene were amplified by polymerase chain reaction and directly sequenced as previously described [8].

Measurement of serum PSTI

Most of the blood samples were taken in the morning after fasting, although it has been shown that the serum PSTI level was not influenced by the diet and was stable throughout the day [25]. None of the CP patients was in an acute exacerbation of CP and none of the RAP patients was in the active phase of RAP. The Serum PSTI concentrations were determined with a commercial radioimmunoassay kit (Ab Bead PSTI; Eiken Chemical, Tokyo, Japan). According to the manufacturer, the normal range of the assay was 4.6–20.0 ng/ml, and the serum PSTI concentration could be measured accurately in the range of 0.31–3700 ng/ml. The procedure was as follows. Briefly, a 50-μl serum sample was incubated with an anti-PSTI-antibody-coated bead and 200-μl 125I-labeled anti-hPSTI antibody at room temperature for 3 h. The unreacted 125I-labeled anti-hPSTI antibody was removed, and the radioactivity bound to the bead was measured with a gamma scintillation counter. A logit-log representation of the calibration curve was used to calculate the serum PSTI concentration, with the results expressed in ng/ml.

Statistical analysis

The results were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 17.0 statistical analysis software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). The significance of differences in the PSTI concentrations was tested by Tukey’s honest significance difference test, and that in ages was tested by Student’s t-test. In addition, we performed a stepwise multiple linear regression analysis to explore the variables independently correlated with the serum PSTI levels. The variables included age, gender, body mass index (BMI), smoking, diagnosis, etiology, and the SPINK1 variants. Also, the serum PSTI concentration data were dichotomized according to the results of receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses. Differences in the frequency of low serum PSTI levels (<6.0 ng/ml) between carriers of the IVS3+2T>C and p.P45S variants and non-carriers were analyzed with the two-sided Fisher’s exact test. Additional odds ratios with 95 % confidence intervals were calculated. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Among the 163 patients with CP or RAP, 20 had genetic variants in the SPINK1 gene. Ten patients had the p.N34S variant (9 heterozygotes and 1 homozygote), 7 had the IVS3+2T>C variant (6 heterozygotes and 1 homozygote), and 2 were compound heterozygotes for the p.N34S and IVS3+2T>C variants (Table 2). As well, a 31-year-old female patient with idiopathic CP had a novel missense variant p.P45S (c.133C>T) in a heterozygous form. She had suffered from multiple attacks of acute pancreatitis since she was 15 years old. She had no family history of pancreatitis. Computed tomography and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography revealed irregular dilatation of the main pancreatic duct with multiple intraductal pancreatic stones throughout the whole pancreas. None of the 73 healthy controls had SPINK1 variants.

The serum PSTI levels in the patients and healthy controls are shown in Table 3. The serum PSTI levels in all patients with CP or RAP did not differ from those in healthy controls. The serum PSTI levels did not differ between patients with CP and those with RAP, or between males and females. The IVS3+2T>C variant and BMI were independently correlated with the serum PSTI levels (P = 0.001 and P = 0.02, respectively). In 42 patients for whom information of the age of onset was available, we examined the correlation between serum PSTI levels and duration of the disease. But no significant correlation was observed (P = 0.24). In the 16 patients with hereditary or familial pancreatitis, the serum PSTI levels (8.3 ± 3.1 ng/ml) were lower than those in the other 147 patients with pancreatitis (13.9 ± 9.7; P = 0.023). Of note, the 16 patients with hereditary or familial pancreatitis were younger (26.6 ± 18.1 years) than the patients with other etiologies (53.1 ± 18.0 years; P < 0.001). In the 10 patients carrying the p.N34S variant, the serum PSTI level was 8.9 ± 3.5 ng/ml, which did not significantly differ from the level in the patients carrying no SPINK1 variants (P = 0.17). The ten patients carrying the p.N34S variant were younger than those with no SPINK1 variants (P < 0.001). The serum PSTI level in the patient with homozygous p.N34S was 6.0 ng/ml. In the 9 patients carrying the IVS3+2T>C variant, including two patients carrying both the p.N34S and IVS3+2T>C variants, the serum PSTI level was lower than that in patients without the SPINK1 variant (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1). The nine patients carrying the IVS3+2T>C variant were younger than those with no SPINK1 variants (P < 0.001). The PSTI level in patients carrying the heterozygous IVS3+2T>C variant was 5.5 ± 3.2 ng/ml, whereas the level in the patient with homozygous IVS3+2T>C was 1.2 ng/ml. The PSTI levels in the two patients carrying both the p.N34S and IVS3+2T>C variants were 3.5 and 3.7 ng/ml. As described below in the ‘Discussion’, the serum PSTI level increased steadily with advancing age [25]. To clarify whether the decreased PSTI levels in patients carrying the IVS3+2T>C variant merely resulted from differences in ages, we recruited relatively young healthy controls (36.6 ± 9.4 years old) and measured their serum PSTI levels. The serum PSTI levels in patients carrying the IVS3+2T>C variant were lower than those in the healthy controls (P < 0.001). The serum PSTI level in the patient carrying the novel missense p.P45S variant was 4.9 ng/ml.

Serum pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor (PSTI) levels in patients carrying the serine protease inhibitor Kazal type 1 (SPINK1) variants. The distribution of the serum PSTI levels in patients with chronic pancreatitis (CP) or recurrent acute pancreatitis (RAP) is shown. Patients were classified based on the presence or absence of the SPINK1 variants. Patients with the IVS3+2T>C variants included those carrying both the IVS3+2T>C and p.N34S variants. The horizontal bars denote the mean value of each group. N.S. not significant

To determine a cut-off value for the serum PSTI level as a predictor of the IVS3+2T>C and p.P45S variants, we performed ROC analysis. A value of 6.0 ng/ml for serum PSTI was taken as the best cut-off value to differentiate IVS3+2T>C and p.P45S carriers from non-carriers and the healthy controls (Fig. 2). According to this cut-off level, the frequency (8/10; 80 %) of a low serum PSTI level in IVS3+2T>C and p.P45S carriers was significantly higher than that (5/153; 3.3 %) in non-carriers (P < 0.01, odds ratio 118.4, 95 % confidence interval 19.8–707.7). Low levels of serum PSTI (<6.0 ng/ml) showed a sensitivity of 80 %, specificity of 97 %, and accuracy of 96 % in the differentiation of IVS3+2T>C and p.P45S carriers from non-carriers.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for serum PSTI concentration. The value of 6.0 ng/ml for serum PSTI was taken as the best cut-off to differentiate IVS3+2T>C and p.P45S carriers from non-carriers in patients with pancreatitis. Low levels of serum PSTI (<6.0 ng/ml) showed a sensitivity of 80 %, specificity of 97 %, and accuracy of 96 % in the differentiation of IVS3+2T>C and p.P45S carriers from non-carriers. AUC area under the curve, CI confidence interval

Discussion

The major findings of this study are as follows: (1) identification of a novel missense variant p.P45S in the SPINK1 gene, (2) the serum PSTI level was decreased in patients with CP or RAP carrying the IVS3+2T>C variant, but not in those carrying the p.N34S variant, (3) the serum PSTI level was not decreased in healthy carriers of the IVS3+2T>C variant, and (4) 6.0 ng/ml was the best cut-off value for serum PSTI to differentiate IVS3+2T>C and p.P45S carriers from non-carriers. Our results suggest that decreased PSTI expression might be the mechanism underlying the susceptibility to pancreatitis in patients carrying the IVS3+2T>C variant. In addition, if the serum PSTI level is low in patients with pancreatitis, the patients might have loss-of-function SPINK1 variants. In a previous large study employing 797 healthy controls, the normal range of the serum PSTI level, which took the lower and upper limits as 2SDs below and above the control mean, was 5.9–22.7 ng/ml, with a mean of 10.6 ng/ml [25]. Our result that set the lower limit at 6.0 ng/ml was compatible with this large study. Although the genetic diagnosis of patients with pancreatitis is not routinely performed in Japan, measurement of the serum PSTI might be useful to identify patients carrying the loss-of-function SPINK1 variants.

We have previously shown that the IVS3+2T>C variant caused skipping of the whole exon 3, resulting in the loss of the trypsin binding site [22]. Functional studies utilizing a minigene system showed that this variant abolished SPINK1 expression at the mRNA level, with consequent loss of inhibitor secretion [13]. Therefore, we supposed that the expression of functionally normal PSTI could be restricted in patients carrying this variant. In the present study, the mean serum PSTI levels in patients with the homozygous and heterozygous IVS3+2T>C variant were 1.2 and 5.7 ng/ml, respectively. It is unclear whether there exists a correlation between the serum PSTI level and that in the pancreatic acinar cells of a given subject. However, our results showing decreased serum PSTI levels in patients carrying this variant agree with previous functional studies and support the concept that, in patients with pancreatitis, the IVS3+2T>C variant decreases PSTI expression not only in the pancreas but also systemically. Interestingly, we found that the serum PSTI level was not significantly decreased in healthy carriers of this variant. Of the five healthy subjects carrying this variant, who were mainly family members of CP patients harboring this variant, only one subject had a decreased serum PSTI level (3.6 ng/ml). In the other four healthy subjects carrying this variant, the serum PSTI level ranged between 6.3 and 14.0 ng/ml, and was not decreased. The maintenance of normal PSTI expression by the non-mutated allele might be a mechanism that protects the carriers from developing pancreatitis.

The serum PSTI level was low (4.9 ng/ml) in our one patient with idiopathic CP carrying the novel missense variant p.P45S. None of the 265 healthy subjects carried this variant (A. Masamune, unpublished observation). Although the functional consequence of this variant remains unknown, the decreased level of serum PSTI might reflect reduced PSTI secretion. Indeed, functional studies using human embryonic kidney 293T cells and Chinese hamster ovarian cells showed that several missense variants, such as p.G48E, p.D50E, p.Y54H, p.R65Q, and p.R67C, reduced PSTI secretion by causing intracellular retention and degradation [23, 24]. In addition, Boulling et al. [26] reported that five additional rare missense variants: p.N64D, p.K66N, p.R67H, p.T69I, and p.C79F, caused a complete loss of PSTI expression.

The p.N34S variant is the most common pancreatitis-associated variant in the SPINK1 gene worldwide [5–9], but the disease-relevant functional effects of the p.N34S variant on SPINK1 structure and function remain obscure. Functional analyses comparing recombinant p.N34S and wild-type SPINK1 found no difference in SPINK1 expression, trypsin inhibitory activity, or binding to trypsin [23, 24, 27]. The aberrant splicing caused by the cosegregating intronic mutations (c.56-37T>C, c.87+268A>G, c.195-606G>A, and c.195-66_65insTTTT) might play a role in the pathogenesis, but reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of total RNA isolated from surgically resected pancreatic tissues of p.N34S homozygotes failed to reveal aberrant splicing of the SPINK1 transcript [28]. In addition, Kereszturi et al. [13] showed that all four intronic variants in linkage disequilibrium with the p.N34S variant were functionally harmless. These studies suggest that SPINK1 expression is not altered in patients carrying the p.N34S variant. In the present study, the serum PSTI level in patients carrying the p.N34S variant tended to be lower (although the difference was not statistically significant; P = 0.17), than the level in those who did not carry SPINK1 variants. Importantly, a previous study showed that the serum PSTI level increased steadily with advancing age [25]. In healthy subjects in their 20 s and 50 s, the mean values of serum PSTI were 9.6 ± 2.6 and 12.2 ± 4.2 ng/ml, respectively [25]. In our study, because patients with the p.N34S variant were significantly younger than those without the SPINK1 variants, the decreased PSTI level in patients with the p.N34S variant might have reflected the difference in age. To clarify whether the p.N34S variant indeed affected the serum PSTI level, we recruited relatively young healthy controls (36.7 ± 9.4 years old) and measured the serum PSTI levels. The serum PSTI level (10.7 ± 2.2 ng/ml) in the healthy controls did not significantly differ from that in the patients carrying the p.N34S variant, suggesting that the p.N34S variant by itself did not affect the serum PSTI level.

In addition to being increased in patients with pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer, serum PSTI levels have also been shown to be increased in patients with extrapancreatic malignancies such as cholangiocarcinoma [29] and cancers of the colon, breast, and prostate [30, 31]. Based on these findings, PSTI is now also known as a tumor-associated trypsin inhibitor that correlates with disease progression and poor prognosis [19]. High expression of PSTI in cancers may be related to its role in cell proliferation and migration, at least through the activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor/mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade [32]. There are structural similarities between SPINK1 and epidermal growth factor in terms of amino acid residues and the presence of 3 intrachain disulfide bridges. Hence, SPINK1 may bind to epidermal growth factor receptor to activate its downstream signaling pathways. It would be of interest to determine whether mutated SPINK1 affects the serum PSTI levels in cancer and also whether mutated SPINK1 affects the cell behaviors of various cancer cells.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CP:

-

Chronic pancreatitis

- RAP:

-

Recurrent acute pancreatitis

- SPINK1:

-

Serine protease inhibitor Kazal type 1

- PSTI:

-

Pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

References

Steer ML, Waxman I, Freedman S. Chronic pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1482–90.

Etemad B, Whitcomb DC. Chronic pancreatitis: diagnosis, classification, and new genetic developments. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:682–707.

Whitcomb DC, Gorry MC, Preston RA, Furey W, Sossenheimer MJ, Ulrich CD, et al. Hereditary pancreatitis is caused by a mutation in the cationic trypsinogen gene. Nat Genet. 1996;14:141–5.

Masson E, Le Maréchal C, Delcenserie R, Chen JM, Férec C. Hereditary pancreatitis caused by a double gain-of-function trypsinogen mutation. Hum Genet. 2008;123:521–9.

Witt H, Luck W, Hennies HC, Classen M, Kage A, Lass U, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding the serine protease inhibitor, Kazal type 1 are associated with chronic pancreatitis. Nat Genet. 2000;25:213–6.

Pfützer RH, Barmada MM, Brunskill AP, Finch R, Hart PS, Neoptolemos J, et al. SPINK1/PSTI polymorphisms act as disease modifiers in familial and idiopathic chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:615–23.

Chen JM, Mercier B, Audrezet MP, Raguenes O, Quere I, Ferec C. Mutations of the pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor (PSTI) gene in idiopathic chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1061–4.

Kume K, Masamune A, Mizutamari H, Kaneko K, Kikuta K, Satoh M, et al. Mutations in the serine protease inhibitor Kazal type 1 (SPINK1) gene in Japanese patients with pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2005;5:354–60.

Aoun E, Chang CC, Greer JB, Papachristou GI, Barmada MM, Whitcomb DC. Pathways to injury in chronic pancreatitis: decoding the role of the high-risk SPINK1 N34S haplotype using meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2003.

Rosendahl J, Witt H, Szmola R, Bhatia E, Ozsvári B, Landt O, et al. Chymotrypsin C (CTRC) variants that diminish activity or secretion are associated with chronic pancreatitis. Nat Genet. 2008;40:78–82.

Rinderknecht H. Activation of pancreatic zymogens. Normal activation, premature intrapancreatic activation, protective mechanisms against inappropriate activation. Dig Dis Sci. 1986;31:314–21.

Bhatia E, Choudhuri G, Sikora SS, Landt O, Kage A, Becker M, et al. Tropical calcific pancreatitis: strong association with SPINK1 trypsin inhibitor mutations. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1020–5.

Kereszturi E, Király O, Sahin-Tóth M. Minigene analysis of intronic variants in common SPINK1 haplotypes associated with chronic pancreatitis. Gut. 2009;58:545–9.

Aoun E, Muddana V, Papachristou GI, Whitcomb DC. SPINK1 N34S is strongly associated with recurrent acute pancreatitis but is not a risk factor for the first or sentinel acute pancreatitis event. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:446–51.

Masamune A, Ariga H, Kume K, Kakuta Y, Satoh K, Satoh A, et al. Genetic background is different between sentinel and recurrent acute pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:974–8.

Ota Y, Masamune A, Inui K, Kume K, Shimosegawa T, Kikuyama M. Phenotypic variability of the homozygous IVS3+2T>C mutation in the serine protease inhibitor Kazal type 1 (SPINK1) gene in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2010;221:197–201.

Ogawa M, Kitahara T, Fujimoto K, Tanaka S, Takatsuka Y, Kosaki G. Serum pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor in acute pancreatitis. Lancet. 1980;2:205.

Lasson A, Borgström A, Ohlsson K. Elevated pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor levels during severe inflammatory disease, renal insufficiency, and after various surgical procedures. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1986;21:1275–80.

Paju A, Stenman UH. Biochemistry and clinical role of trypsinogens and pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2006;43:103–42.

Nakano I, Funakoshi A, Sumii T, Miyazaki K, Oogami Y, Kimura T, et al. Appearance mechanism and molecular heterogeneity of serum pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor (PSTI). Gastroenterol Jpn. 1985;20:354–60.

Satake K, Inui A, Sogabe T, Yoshii Y, Nakata B, Tanaka H, et al. The measurement of serum immunoreactive pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor in gastrointestinal cancer and pancreatic disease. Int J Pancreatol. 1988;3:323–31.

Kume K, Masamune A, Kikuta K, Shimosegawa T. [-215G>A; IVS3+2T>C] mutation in the SPINK1 gene causes exon 3 skipping and loss of the trypsin binding site. Gut. 2006;55:1214.

Király O, Wartmann T, Sahin-Tóth M. Missense mutations in pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor (SPINK1) cause intracellular retention and degradation. Gut. 2007;56:1433–8.

Boulling A, Le Maréchal C, Trouvé P, Raguénès O, Chen JM, Férec C. Functional analysis of pancreatitis-associated missense mutations in the pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor (SPINK1) gene. Eur J Hum Genet. 2007;15:936–42.

Ogawa M. Normal level and normal range of serum PSTI concentration. In: Kosaki G, Ogawa M, editors. Pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor. Tokyo: Igaku Tosho Shuppan; 1985. p. 91–3 (in Japanese).

Boulling A, Keiles S, Masson E, Chen JM, Férec C. Functional analysis of eight missense mutations in the SPINK1 gene. Pancreas. 2011;41:329–30.

Kuwata K, Hirota M, Shimizu H, Nakae M, Nishihara S, Takimoto A, Mitsushima K, Kikuchi N, Endo K, Inoue M, Ogawa M. Functional analysis of recombinant pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor protein with amino-acid substitution. J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:928–34.

Masamune A, Kume K, Takagi Y, Kikuta K, Satoh K, Satoh A, Shimosegawa T. N34S mutation in the SPINK1 gene is not associated with alternative splicing. Pancreas. 2007;34:423–8.

Tonouchi A, Ohtsuka M, Ito H, Kimura F, Shimizu H, Kato M, Nimura Y, Iwase K, Hiwasa T, Seki N, Takiguchi M, Miyazaki M. Relationship between pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor and early recurrence of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma following surgical resection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1601–10.

Gaber A, Johansson M, Stenman UH, Hotakainen K, Pontén F, Glimelius B, Bjartell A, Jirström K, Birgisson H. High expression of tumour-associated trypsin inhibitor correlates with liver metastasis and poor prognosis in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1540–8.

Paju A, Hotakainen K, Cao Y, Laurila T, Gadaleanu V, Hemminki A, Stenman UH, Bjartell A. Increased expression of tumor-associated trypsin inhibitor, TATI, in prostate cancer and in androgen-independent 22Rv1 cells. Eur Urol. 2007;52:1670–9.

Ozaki N, Ohmuraya M, Hirota M, Ida S, Wang J, Takamori H, Higashiyama S, Baba H, Yamamura K. Serine protease inhibitor Kazal type 1 promotes proliferation of pancreatic cancer cells through the epidermal growth factor receptor. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:1572–81.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (to K. Kume, to A. Masamune, and to T. Shimosegawa), and by the Research Committee of Intractable Pancreatic Diseases (Principal investigator: T. Shimosegawa), provided with funding by the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare of Japan.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kume, K., Masamune, A., Ariga, H. et al. Do genetic variants in the SPINK1 gene affect the level of serum PSTI?. J Gastroenterol 47, 1267–1274 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-012-0590-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-012-0590-3