Abstract

Background

Surgical site infections (SSIs), particularly organ/space SSIs, remain a common cause of major morbidity after hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Methods

Risk factors for SSIs were analyzed in 359 patients who underwent hepatectomy for HCC between 2001 and 2010. The causative bacteria, management, outcome, and characteristics of organ/space SSIs were investigated.

Results

Anatomic hepatectomy was performed for 296 patients (82.5%), and repeat hepatectomy was carried out for 59 patients (16.4%). SSIs developed in 52 patients (14.5%; incisional, 24 cases; organ/space, 31 cases [3 patients showed both incisional and organ/space SSIs]). No in-hospital mortality related to incisional or organ/space SSIs was encountered. Independent risk factors for SSIs were repeat hepatectomy and operative time ≥280 min. Independent risk factors for organ/space SSIs were repeat hepatectomy and bile leakage. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus was detected more frequently in organ/space SSIs after repeat hepatectomy than after initial hepatectomy.

Conclusions

Repeat hepatectomy and bile leakage represent independent risk factors for organ/space SSIs after hepatectomy for HCC. Establishing treatment strategies is important for preventing postoperative bile leakage and reducing the high rate of organ/space SSIs after repeat hepatectomy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Thanks to advances in surgical techniques and perioperative management, the in-hospital mortality rate after hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) has been greatly improved [1–3]. However, relatively high morbidity rates remain problematic, and surgical site infections (SSIs), particularly organ/space SSIs, are still a common cause of major morbidity after hepatectomy for HCC [4–9]. In recent years, attention has increasingly been focused on the accurate identification and monitoring of SSIs. The National Nosocomial Infection Surveillance (NNIS) system established by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States provides a comprehensive monitoring system that reports on trends in SSIs. The NNIS system reported a high incidence of SSIs following colon surgery, ranging from 3.2 to 13.3% (median) during the period from January 1992 through June 2004 [10]. However, the risk factors for organ/space SSIs after hepatectomy for HCC under CDC guidelines have yet to be fully investigated.

In many centers, various types of hepatectomy have recently been performed depending on the degree of hepatic functional reserve and the location of the HCC. Anatomic hepatectomy for HCC, including subsegmentectomy, reportedly contributes to improving the prognosis of patients with HCC [11–13]. In addition, the rate of repeat hepatectomies for HCC recurrence has recently increased from 10 to 31% as the prognosis for patients with HCC has improved [14–18].

In our institution, anatomic and repeat hepatectomies for HCC have been performed aggressively [9, 13, 19]. We investigated risk factors for SSIs, incisional SSIs, and organ/space SSIs following hepatectomies for HCC in the present series, which included a large number of patients with a high proportion of anatomic or repeat hepatectomies. Furthermore, we also investigated the causative bacteria, management, and outcomes of organ/space SSIs, and strategies to reduce organ/space SSIs were considered.

Methods

Patients

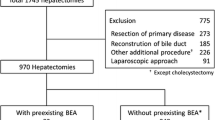

Medical records of 359 patients who underwent hepatectomy without biliary reconstruction for HCC in our department between January 1, 2001, and March 31, 2010, were studied retrospectively. The patients comprised 292 men and 67 women, with a mean age of 65 years (range 32–89 years). The etiology of liver disease was hepatitis C virus in 163 patients, hepatitis B virus in 122 patients, both hepatitis C virus and hepatitis B virus in 31 patients, alcoholic liver disease in 16 patients, and other in 27 patients. Child–Pugh class was A in 332 patients and B in 27 patients. A total of 296 patients (82.5%) underwent anatomic hepatectomy including subsegmentectomy. Repeat hepatectomy was performed for 59 patients (16.4%). Repeat hepatectomy was indicated when all tumors detected on preoperative imaging could be resected within the hepatic functional reserve. When recurrent HCC tumors were ≤2 cm in maximum diameter and ≤3 tumors were present, percutaneous ablation therapies were selected despite the feasibility of repeat hepatectomy, depending on tumor location in the liver.

Surgical procedure

Laparotomy was performed through a J incision in 287 patients, a Mercedes incision in 33 patients, a midline incision in 23 patients, and a thoraco-abdominal incision in 16 patients. Preoperative cholangiography was not usually performed. Intraoperative ultrasonography was performed to determine the extent of HCC and the line of parenchymal transection. Parenchymal transection was performed using an ultrasonic dissector (Sonop 5000; Aloka, Tokyo, Japan) combined with bipolar electrocautery. Glisson’s pedicles in the livers dissected by the ultrasonic dissector were ligated and small pedicles were resected using metallic surgical clips. For hemihepatectomies or extended operations, hilar dissection was performed to divide the ipsilateral branches of the hepatic artery and portal vein. The hepatic duct was exposed inside the liver during parenchymal transection and was ligated or oversewn using fine non-absorbable sutures. Parenchymal transection in hemihepatectomy or extended operations was performed largely without any occlusion of vascular inflow. For segmentectomies or subsegmentectomies, Glisson’s pedicle was transected at the hepatic hilus and an intermittent Pringle maneuver was applied during parenchymal transection.

Intraoperative cholangiography was undertaken for selected patients when the integrity of the bile duct was in doubt. A bile leakage test using a cholangiography catheter was also performed for selected patients when many Glisson’s pedicles were exposed in the plane of the hepatic resection. In principle, two abdominal drainage tubes were systematically positioned and the method of placing the drainage tubes was changed according to the type of hepatectomy. In hemihepatectomy, one drainage tube was placed on the cut surface of the liver and another was positioned at the Winslow hiatus. In subsegmentectomy and segmentectomy, one drainage tube was placed on the cut surface of the liver and another was positioned in the right subphrenic space. From 2001 to 2005, an open drainage system was employed using 12-mm silicone Penrose drains (Kaneka, Osaka, Japan). From 2006 to 2010, a closed drainage system was used with 24-Fr BLAKE silicone drains (Johnson & Johnson, Somerville, NJ, USA). Drains were removed when the drainage was serous and contained no bile, usually around postoperative day 5. Abdominal incisions were closed in two layers, including fascia and skin. Fascia closure was performed with interrupted sutures using monofilament absorbable sutures. Subcutaneous suturing was basically performed using absorbable sutures, and the skin was closed using staples. Closures of midline and transverse incisions were undertaken in the same manner.

Antimicrobial prophylaxis

Prophylactic antibiotic regimens were as follows. With initial hepatectomy, a first-generation cephalosporin was injected intravenously within 30 min prior to skin incision. In patients who underwent operations lasting longer than 3 h, additional antimicrobial agents were injected intravenously every 3 h, as recommended by CDC guidelines [10]. These agents were also administered up to postoperative day 2. In repeat hepatectomy, a second-generation cephalosporin was injected intravenously in the same manner as in the initial hepatectomy and continued until postoperative day 3.

Intervention for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)

With the exception of two emergency cases, all patients underwent preoperative evaluation, including nasal culture for MRSA. As a result, we found that 9 of the 359 patients (2.5%) showed colonization with MRSA on admission to our institution. In these 9 patients with detection of MRSA colonization from preoperative nasal cultures, decolonization was performed using intranasal mupirocin therapy (administered twice daily for 3–5 days preoperatively). Prophylactic intravenous infusion of vancomycin was not applied in the 9 patients with intranasal MRSA colonization.

Definition of SSIs

SSIs were defined according to the NNIS system [10]. Using these criteria, SSIs are classified as either incisional (superficial or deep) or organ/space. Criteria for a superficial incisional SSI included infection occurring at the incision site within 30 days after surgery that involved only the skin and subcutaneous tissue and at least one of the following: (1) pus discharge from the incision; (2) bacteria isolated from a sample culture from the superficial incision; (3) localized pain, tenderness, swelling, redness, or heat; and (4) wound dehiscence. Criteria for a deep incisional SSI included infection of the fascia or muscle related to the surgical procedure occurring within 30 days after surgery and at least one of the following: (1) pus discharge from the deep incision; (2) spontaneous dehiscence of the incision; or (3) deliberate opening of the incision when the patient displayed the previously described signs and symptoms of infection. The definition of organ/space SSI was based on postoperative findings of at least one of the following: (1) purulent drainage from a drain without macroscopic bile discharge; or (2) intraabdominal collection of purulent fluid confirmed at the time of reoperation or percutaneous drainage. If intraabdominal collection at the time of reoperation or percutaneous drainage contained macroscopic bile discharge, bile leakage was considered to be present. If the purulent fluid was drained first and macroscopic bile leakage subsequently became apparent, this was defined as bile leakage. In contrast, if drainage of purulent fluid was still observed after the cessation of macroscopic bile leakage, this was defined as an organ/space SSI.

Analysis of risk factors for SSIs and organ/space SSIs

Patient demographics, operative and tumor factors, and preoperative liver function were evaluated to determine impacts on the occurrence of SSIs, incisional SSIs, and organ/space SSIs. Preoperative factors included patient age, sex, etiology of liver disease, Child–Pugh classification, indocyanine green dye retention rate at 15 min (ICG-R15), serum albumin, history of diabetes mellitus, previous radiofrequency ablation (RFA), and previous transarterial chemoembolization (TACE). The cut-off level for ICG-R15 was set at 20%, because an ICG-R15 level of <20% has been reported as the safe limit for bisegmentectomy [3, 4, 6]. Surgical factors were evaluated for the type of skin incision, type of hepatectomy, number of hepatectomies, blood loss, operative time, blood transfusion, and method of abdominal drainage. With regard to the type of hepatectomy, anterior segmentectomies and medial (S4) segmentectomies were subgrouped for analysis. The cut-off point for operative time was determined by an analysis of the receiver operating characteristics curve for SSIs. Optimal cut-off for operative time was 277 min, offering 74.1% sensitivity and 68.0% specificity. We thus used 280 min as the cut-off level for operative time. Tumor factors included the number of HCC lesions and the maximum diameter of the HCC. The cut-off level for HCC diameter was determined according to the results of previous reports that analyzed risk factors for morbidity after hepatectomy for HCC [3, 4, 6, 9].

Investigation of characteristics of organ/space SSIs

Organ/space SSIs were classified according to the modified Clavien system (Dindo et al. [20]): grade I, minor risk events not requiring special treatment; grade II, potentially life-threatening complications requiring pharmacological treatment; grade III, complications requiring surgical, endoscopic, or radiological intervention, either with (III-b) or without (III-a) general anesthesia; grade IV, life-threatening complications involving dysfunction of one (IV-a) or multiple (IV-b) major organs; and grade V, complications resulting in the death of the patient. The management and outcomes for 31 patients with organ/space SSIs were investigated. In addition, the causative bacterium was identified for both incisional and organ/space SSIs. Furthermore, in patients with organ/space SSIs, pre- and intraoperative parameters, causative bacteria, and hospital stay were compared between groups classified by the number of hepatectomies.

Statistical analysis

Values for operative time, blood loss, and postoperative hospital stay are presented as means ± standard error of the mean. Differences in qualitative variables were assessed using Fisher’s exact test or the χ2 test, while differences in quantitative variables were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney test. Uni- and multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to identify risk factors for SSIs, incisional SSIs, and organ/space SSIs, based on the 18 above-mentioned clinical factors. Relative risk was described by the estimated odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval. Two-sided P values were computed and an effect was considered significant at the level of P ≤ 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS II statistical software (SPSS, Tokyo, Japan).

Results

Risk factors for SSIs (Tables 1, 4)

SSIs developed in 14.5% of patients (n = 52), and 3 patients showed both incisional and organ/space SSIs. Univariate logistic regression analysis revealed several factors associated with an increased risk of developing SSIs. Repeat hepatectomy influenced the risk of developing SSIs, with an OR of 8.27 for initial hepatectomy. In contrast, neither previous RFA nor TACE exerted any significant impact on the occurrence of SSIs. Operative time of ≥280 min was associated with an increased risk (OR 4.46; P < 0.001). The presence of blood transfusion influenced the risk of developing SSIs. The presence of bile leakage was associated with an increased risk of SSIs (OR 6.40; P = 0.002). Multivariate analysis regarding SSIs confirmed both repeat hepatectomy and operative time of ≥280 min as independent risk factors (Table 4).

Risk factors for incisional SSIs (Tables 2, 4)

The incidence of incisional SSIs was 6.7% (n = 24). Univariate logistic regression analysis revealed that the presence of blood transfusion was associated with an increased risk of developing an incisional SSI. The type of skin incision classified according to the presence or absence of a transverse incision showed no significant influence on the occurrence of incisional SSIs in this series. Multivariate analysis regarding incisional SSI confirmed the presence of blood transfusion as an independent risk factor (Table 4).

Risk factors for organ/space SSIs (Tables 3, 4)

The incidence of organ/space SSIs was 8.6% (n = 31). Univariate logistic regression analysis revealed several factors associated with an increased risk of developing an organ/space SSI. Repeat hepatectomy influenced the risk of developing an organ/space SSI, with an OR of 4.29 compared to initial hepatectomy. In contrast, neither previous RFA nor TACE exerted any significant impact on the occurrence of organ/space SSIs. The method of abdominal drainage (open Penrose drains or closed suction drains) showed no significant influence. Operative time of ≥280 min was associated with an increased risk of an organ/space SSI (OR 2.99; P < 0.001). The presence of bile leakage was likewise associated with an increased risk (OR 3.16; P < 0.001). Multivariate analysis regarding organ/space SSIs confirmed both repeat hepatectomies and the presence of bile leakage as independent risk factors (Table 4).

Management and outcomes of organ/space SSIs

The organ/space SSIs in 31 patients were classified as follows: abscess on the cut surface of the liver in 26 patients; right subphrenic abscess in 4 patients; and liver abscess in 1 patient. One of the 31 patients with an organ/space SSI was treated by reoperation because of a right subphrenic abscess, but died owing to myocardial infarction. Eleven patients needed percutaneous drainage of organ/space SSIs and all of them were cured. Organ/space SSIs in 19 patients healed with irrigation of the pre-existing drain. As a result, the 31 patients with organ/space SSIs were stratified according to the modified Clavien system as follows: grade I, 0 patients; II, 13 patients; III-a, 15 patients; III-b, 2 patients; IV-a, 1 patient; IV-b, 0 patients; and V, 0 patients. No mortality was associated with organ/space SSIs in this series, but the postoperative hospital stay was significantly longer for patients with organ/space SSIs (53 ± 7.2 days) than for patients without organ/space SSIs (27 ± 0.9 days, P = 0.001).

Bacteria causing incisional and organ/space SSIs (Table 5)

Causative bacteria for incisional and organ/space SSIs comprised gram-positive cocci (GPC) in 17 patients (70.8%) and 19 patients (61.3%), and gram-negative rods (GNR) in 6 patients (25.0%) and 9 patients (29.0%), respectively, indicating a similar proportion of GPC and GNR in both incisional and organ/space SSIs. MRSA was the causative bacteria in 12 of the 19 patients with an organ/space SSI caused by GPC.

Comparison between initial and repeat hepatectomies in patients with organ/space SSIs (Table 6)

We compared clinical parameters between initial and repeat hepatectomies in patients with organ/space SSIs. HCC diameter in patients with organ/space SSI who underwent initial hepatectomy was significantly larger than that in patients who underwent repeat hepatectomy. No significant differences were seen between the groups in any other preoperative parameters, including patient demographics and preoperative liver function. No significant differences were identified between the two groups in operative parameters, including blood loss, operative time, and blood transfusion. The rate of bile leakage was similar in the two groups. In contrast, in terms of the bacteria causing organ/space SSIs, MRSA was detected significantly more frequently in the repeat hepatectomy group than in the initial group.

Discussion

Rates of SSIs after hepatectomy for liver tumors and benign lesions have been reported to range from 4.6 to 25.2% [21–28]. Several studies have indicated that the incidence of SSIs after hepatectomy is higher for HCC than for metastatic liver cancer [25, 26]. A high prevalence of infectious complications in patients with cirrhosis or chronic liver dysfunction has been demonstrated after abdominal surgical procedures [29–31], and this can be attributed to the impaired reticulo-endothelial system [32]. In addition, Schindl et al. [33] reported a close relationship between the volume of resected liver and the incidence of postoperative infection. The high rate of major hepatectomy (hemi-hepatectomy or tri-segmentectomy) in the present series might be associated with the high incidence of SSIs (14.5%).

In the 1980s and 1990s, organ/space SSI formation after hepatectomy was reported as a fatal complication causing liver failure and death [34–36]. Although rates of organ/space SSIs after hepatectomy have been reported as ranging from 4.7 to 25%, rates of hospital mortality caused by organ/space SSIs have declined [6–9, 22, 26]. Several groups have reported high patient age and the presence of diabetes mellitus as independent risk factors for organ/space SSIs [22, 25]. However, these variables were not identified as independent risk factors for organ/space SSI in the present study. Our key result was the identification of repeat hepatectomy as an independent risk factor for organ/space SSIs, suggesting that treatment strategies need to be established to reduce the high rate of organ/space SSIs after repeat hepatectomy.

In the present study, MRSA was detected more frequently in organ/space SSIs after repeat hepatectomy compared with the detection rate after initial hepatectomy. We assume that most organ/space SSIs with MRSA after repeat hepatectomy develop as a result of contamination arising from the surgical procedure coming into contact with intraabdominal MRSA colonization or micro-abscesses containing MRSA that had been formed after the initial hepatectomy. This assumption may be supported by our finding that the method of abdominal drainage (open or closed) had no significant influence on the occurrence of organ/space SSIs. If this assumption is valid, preoperative MRSA intervention, consisting of nasal culture and decolonization of nasal MRSA, will not greatly reduce the occurrence of organ/space SSIs involving MRSA after repeat hepatectomy. Walsh et al. [37] recently reported that an MRSA intervention program, in which all patients received intranasal mupirocin and patients colonized with MRSA received prophylactic intravenous infusion of vancomycin, resulted in near-complete and sustained elimination of MRSA SSIs after cardiac surgery. Regarding patients who undergo repeat hepatectomies, the preoperative detection of intraabdominal colonization or a micro-abscess containing MRSA is difficult. MRSA intervention programs thus need to be improved, particularly for patients who undergo repeat hepatectomies, by considering the prophylactic intravenous administration of vancomycin.

In the present study, repeat hepatectomy was identified as an independent risk factor for SSIs and organ/space SSIs, but previous RFA and TACE were not independent risk factors. Repeat hepatectomy for recurrent HCC is useful in establishing good long-term outcomes. The cumulative 5-year survival rates after a second hepatectomy have been reported to be 41–69% [14–19]. RFA has recently been confirmed as a safe and promising therapy for recurrent HCC after hepatectomy. However, sufficient evidence does not exist to confirm whether RFA actually improves long-term outcomes. The cumulative 5-year survival rates after RFA for recurrent HCC after hepatectomy have been reported to be 18–51.6% [38–40]. RFA is sometimes ineffective for HCC on the liver surface or near large vessels. In addition, postoperative adhesions between the remnant liver and gastrointestinal tract may prevent safe percutaneous RFA in patients with recurrent HCC.

In several previous reports, similar to findings in the present study, bile leakage has also been identified as an independent risk factor for organ/space SSIs [22, 24, 28]. We have previously reported that latent stricture of the biliary anatomy owing to previous treatment for HCC is the main cause of intractable bile leakage requiring invasive treatment, such as endoscopic therapy or interventional biliary drainage [9]. At present, we perform preoperative assessment of biliary anatomy, using computed tomography cholangiography or magnetic resonance imaging with cholangiopancreaticography in selected patients: (1) patients who underwent anatomic hepatectomy; (2) patients who received RFA for HCC located adjacent to Glisson’s capsule in the hepatic hilar region; or (3) patients who received TACE in which embolization of the feeding artery was undertaken from the level of the left or right hepatic artery.

In conclusion, this study has revealed that repeat hepatectomy and the presence of postoperative bile leakage are independent risk factors for organ/space SSIs, and MRSA is the main causative bacteria in organ/space SSIs after repeat hepatectomy for HCC. The establishment of treatment strategies is important for preventing postoperative bile leakage and for reducing the high rate of organ/space SSIs after repeat hepatectomy.

References

Fan ST, Lo CM, Liu CL, Lam CM, Yuen WK, Yeung C, et al. Hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma: toward zero hospital deaths. Ann Surg. 1999;229:323–30.

Fong Y, Sun RL, Jarnagin W, Blumgart LH. An analysis of 412 cases of hepatocellular carcinoma at a Western center. Ann Surg. 1999;229:790–800.

Torzilli G, Makuuchi M, Inoue K, Takayama T, Sakamoto Y, Sugawara Y, et al. No mortality liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic and noncirrhotic patients. Arch Surg. 2007;134:984–92.

Shimada M, Takenaka K, Fujiwara Y, Gion T, Shirabe K, Yanaga K, et al. Risk factors linked to postoperative morbidity in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg. 1998;85:195–8.

Belghiti J, Hiramatsu K, Benoist S, Massault P, Sauvanet A, Farges O. Seven hundred forty-seven hepatectomies in the 1990s: an update to evaluate the actual risk of liver resection. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191:38–46.

Capussotti L, Muratore A, Amisano M, Polastri R, Bouzari H, Massucco P. Liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma on cirrhosis: analysis of mortality, morbidity and survival—a European single center experience. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2005;31:986–93.

Taketomi A, Kitagawa D, Itoh S, Harimoto N, Yamashita Y, Gion T, et al. Trends in morbidity and mortality after hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: an institute’s experience with 625 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:580–7.

Virani S, Michaelson J, Hutter M, Lancaster RT, Warshaw AL, Henderson WG, et al. Morbidity and mortality after liver resection: results of the Patient Safety in Surgery study. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:1284–92.

Sadamori H, Yagi T, Matsuda H, Shinoura S, Umeda Y, Yoshida R, et al. Risk factors for major morbidity after hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma in 293 recent cases. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2010;17:709–18.

CDC NNIS System. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) system report, data summary from January 1992 to June 2004, issued October 2004. Am J Infect Control. 2004;32:470–85.

Hasegawa K, Kokudo N, Imamura H, Matsuyama Y, Aoki T, Minagawa M, et al. Prognostic impact of anatomic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2005;242:252–9.

Eguchi S, Kanematsu T, Arii S, Okazaki M, Okita K, Omata M, Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan, et al. Comparison of the outcomes between an anatomical subsegmentectomy and a non-anatomical minor hepatectomy for single hepatocellular carcinomas based on a Japanese nationwide survey. Surgery. 2008;143:469–75.

Sadamori H, Matsuda H, Shinoura S, Umeda Y, Yoshida R, Satoh D, et al. Anatomical subsegmentectomy in the lateral segment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56:971–7.

Farges O, Regimbeau JM, Belghiti J. Aggressive management of recurrence following surgical resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:1275–80.

Shimada M, Takenaka K, Taguchi K, Fujiwara Y, Gion T, Kajiyama K, et al. Prognostic factors after repeat hepatectomy for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. 1998;227:80–5.

Poon RT, Fan ST, Lo CM, Liu CL, Wong J. Intrahepatic recurrence after curative resection of hepatocellular carcinoma: long-term results of treatment and prognostic factors. Ann Surg. 1999;229:216–22.

Minagawa M, Makuuchi M, Takayama T, Kokudo N. Selection criteria for repeat hepatectomy in patients with recurrence hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2003;238:703–10.

Itamoto T, Nakahara H, Amano H, Kohashi T, Ohdan H, Tashiro H, et al. Repeat hepatectomy for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma. Surgery. 2007;141:589–97.

Umeda Y, Matsuda H, Sadamori H, Matsukawa H, Yagi T, Fujiwara T. A prognostic model and treatment strategy for intrahepatic recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection. World J Surg. 2011;35:170–7.

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–13.

Wu CC, Yeh DC, Lin MC, Liu TJ, P’eng FK. Prospective randomized trial of systemic antibiotics in patients undergoing liver resection. Br J Surg. 1998;85:489–93.

Togo S, Matsuo K, Tanaka K, Matsumoto C, Shimizu T, Ueda M, et al. Perioperative infection control and its effectiveness in hepatectomy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1942–8.

Shiba H, Ishii Y, Ishida Y, Wakiyama S, Sakamoto T, Ito R, et al. Assessment of blood-products use as predictor of pulmonary complications and surgical infection after hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16:69–74.

Okabayashi T, Nishimori I, Yamashita K, Sugimoto T, Yatabe T, Maeda H, et al. Risk factors and predictors for surgical site infection after hepatic resection. J Hosp Infect. 2009;73:47–53.

Kobayashi S, Gotohda N, Nakagohri T, Takahashi S, Konishi M, Kinoshita T. Risk factors of surgical site infection after hepatectomy for liver cancers. World J Surg. 2009;33:312–7.

Uchiyama K, Ueno M, Ozawa S, Kiriyama S, Kawai M, Hirono S, et al. Risk factors for postoperative infectious complications after hepatectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2011;18:67–73.

Togo S, Kubota T, Takahashi T, Yoshida K, Matsuo K, Morioka D, et al. Usefulness of absorbable sutures in preventing surgical site infection in hepatectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1041–6.

Arikawa T, Kurokawa T, Ohwa Y, Ito N, Kotake K, Nagata H, et al. Risk factors for surgical site infection after hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011;58:143–6.

Wong R, Rappaport W, Witte C, Hunter G, Jaffe P, Hall K, et al. Risk of nonshunt abdominal operation in the patient with cirrhosis. J Am Coll Surg. 1994;179:412–6.

Mansour A, Watson W, Shayani V, Pickleman J. Abdominal operations in patients with cirrhosis: still a major surgical challenge. Surgery. 1997;122:730–5.

Pessaux P, Msika S, Atalla D, Hay JM, Flamant Y, French Association for Surgical Research. Risk factors for postoperative infectious complications in noncolorectal abdominal surgery: a multivariate analysis based on a prospective multicenter study of 4718 patients. Arch Surg. 2003;138:314–24.

Schindl MJ, Millar AM, Redhead DN, Fearon KC, Ross JA, Dejong CH, et al. The adaptive response of the reticuloendothelial system to major liver resection in humans. Ann Surg. 2006;243:507–14.

Schindl MJ, Redhead DN, Fearon KC, Garden OJ, Wigmore SJ, Edinburgh Liver Surgery and Transplantation Experimental Research Group (eLISTER). The value of residual liver volume as a predictor of hepatic dysfunction and infection after major liver resection. Gut. 2005;54:289–96.

Yanaga K, Kanematsu T, Takenaka K, Sugimachi K. Intraperitoneal septic complications after hepatectomy. Ann Surg. 1986;203:148–52.

Anderson R, Saarela A, Tranberg KG, Bengmark S. Intraabdominal abscess formation after major liver resection. Acta Chir Scand. 1990;156:707–10.

Nagasue N, Kohno H, Tachibana M, Yamanoi A, Ohmori H, EI-Assai O. Prognostic factors after hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma associated with Child-Turcotte class B and C cirrhosis. Ann Surg. 1999;229:84–90.

Walsh EE, Greene L, Kirshner R. Sustained reduction in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus wound infections after cardiothoracic surgery. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:68–73.

Lau WY, Lai EC. The current role of radiofrequency ablation in the management of hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review. Ann Surg. 2009;249:20–5.

Choi D, Lim HK, Rhim H, Kim YS, Yoo BC, Paik SW, et al. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy: long-term results and prognostic factors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:2319–29.

Taura K, Ikai I, Hatano E, Fujii H, Uyama N, Shimahara Y. Implication of frequent local ablation therapy for intrahepatic recurrence in prolonged survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing hepatic resection: an analysis of 610 patients over 16 years old. Ann Surg. 2006;244:265–73.

Conflict of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Sadamori, H., Yagi, T., Shinoura, S. et al. Risk factors for organ/space surgical site infection after hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma in 359 recent cases. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 20, 186–196 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00534-011-0503-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00534-011-0503-5