Abstract

Objectives

Several delivery models of palliative care are currently available: hospital-based, outpatient-based, home-based, nursing home-based, and hospice-based. Weighing the differences in costs of these delivery models helps to advise on the future direction of expanding palliative care services. The objective of this review is to identify and summarize the best available evidence in the US on cost associated with palliative care for patients diagnosed with cancer.

Methods

The systematic review was carried out of studies conducted in the US between 2008 and 2018, searching PubMed, Medline, the Cochrane library, CINAHL, EconLit, the Social Science Citation Index, Embase, and Science Citation Index, using the following terms: palliative, cancer, carcinoma, cost, and reimbursement.

Results

The initial search identified 748 articles, of which 16 met the inclusion criteria. Eight studies (50%) were inpatient-based, four (25%) were combined outpatient/inpatient, two (12.5%) reported only on home-based palliative services, and two (12.5%) were in multiple settings. Most included studies showed that palliative care reduced the cost of health care by $1285–$20,719 for inpatient palliative care, $1000–$5198 for outpatient and inpatient combined, $4258 for home-based, and $117–$400 per day for home/hospice, combined outpatient/inpatient palliative care.

Conclusion

Receiving palliative care after a cancer diagnosis was associated with lower costs for cancer patients, and remarkable differences exist in cost saving across different palliative care models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Palliative care as a medical specialty focusing on care for advanced cancer patients is growing at a rapid rate in the United States [1, 2]. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) defines advanced cancer patients as those who have distant metastases, late stage disease, life-limiting cancer, and/or prognosis of 6 to 24 months [3]. According to WHO, “Palliative care is an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial, and spiritual” [4]. Growing evidence has demonstrated the benefits of palliative care to cancer patients, including improvements in quality of life [5,6,7,8,9,10,11], extended survival [12,13,14], reduction in length of hospital stay, less inpatient admissions, and emergency department and physician office visits [8, 15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Studies have also shown palliative care to be associated with fewer depressive symptoms [6, 22], improved physical and psychological symptoms [10, 23], improved patient satisfaction [5, 17], and provider communication [17]. When offered early, palliative care decreases end-of-life chemotherapy use and increases referral to hospice care to maximize quality of life in the last days [18, 24, 25]. In light of current evidence, the ASCO recommends that clinicians integrate palliative care services in standard oncology practice and provide dedicated palliative care services to patients with advanced cancer early in the disease course [19]. As the number of elderly patients diagnosed with advanced cancer escalates, palliative care will play an increasingly important role in cancer care.

The importance of cost analysis in cancer care is well acknowledged, yet current research on the cost associated with palliative care for patients diagnosed with cancer is limited and disparate. Some studies [26, 27] examining the cost associated with palliative care in the inpatient setting among patients diagnosed with terminal illness have indicated that palliative care may be a cost-saving practice, whereas others [20, 28] have suggested that the cost difference between the palliative care group and the control group was statistically insignificant or cost was higher for the palliative care group. Estimating the cost associated with palliative care can be challenging, especially considering various palliative care delivery models. Currently, at least five delivery models of palliative care are available for cancer patients: hospital-based, outpatient-based, home-based, nursing home-based, and hospice-based palliative care [21]. Yet to date, no study has compared the economic impact of palliative services on cancer care across various palliative care delivery models.

As the number of palliative care programs grows, weighing the differences in costs related to palliative care is needed to inform the expansion of palliative care services. We conducted a preliminary search in PubMed and Google Scholar for existing systematic reviews on the topic and no review identical to the one proposed was found. We performed a systematic review of studies published from 2000 to 2018, which measured the cost associated with palliative care in patients diagnosed with cancer to better understand palliative care costs for cancer patients and their variations by different delivery settings. We critically appraised the available evidence to determine costs associated with palliative care and costs relative to the benefits of palliative care from the perspectives of payer, provider, and their variations by delivery settings to inform decisions about implementation and delivery of palliative care.

Methods

We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [29] for conducting our systematic review. The topic was registered in the PROSPERO database.

Search strategy

A medical librarian searched the following 10 databases: PubMed (NLM), Web of Science, EbscoHost’s Academic Search Premier, CINAHL, EconLit and Health Business Full Text, ProQuest’s, ABI/INFORM and Dissertations and Theses Global databases, the Cochrane Library (Wiley), and ClinicalTrials.gov website. The searches were conducted October 4–15, 2018, using subject headings as well as truncated and phrase search terms in title and abstract as available for neoplasms of all histologic types at all sites, palliative care, costs, economics, claims, fees, charges, expenditures, dollars, monetary value, bills, spending, pricing, payment, budget, and United States. Subject terms were explored when applicable. The studies were limited to those published between January 2008 and July 2018, involving humans. The bibliographies of articles remaining after initial selection were screened for additional potentially suitable articles for inclusion. The bibliographies of relevant review articles were hand-searched to identify additional studies that may fit the study scope. Only publications in peer-reviewed journals were included, and all other publications such as case report, book, conference abstracts, letters, and comments were excluded. The publications resulting from comprehensive search were exported into EndNote Web, manually de-duplicated and shared with the study team. We also searched the gray literature for economic evaluations on the topic of interest using Scopus and ProQuest database to find conference abstracts, dissertations, and theses. The full search strategy is available in supplemental material.

Inclusion criteria

We used the PICO [30] framework to develop our inclusion criteria and search strategy. PICO is a mnemonic that stands for (P) population, (I) intervention, (C) context/setting, and (O) outcomes. We included all clinical studies that assessed the cost (outcome) associated with palliative care (intervention) in patients diagnosed with cancer (population) and were conducted in the US (context/setting) in our review. For the purpose of determining inclusion in the review, we operationalized palliative care as a consultation with a palliative care specialist of a palliative care team and included papers that met this operational definition of palliative care. Studies included were limited to those in the US, and studies from other developed countries were excluded because of the differences in healthcare expenditure and utilization of end-of-life care for patients diagnosed with cancer between different countries [31]. The costs had to be clearly reported in US dollars ($) to allow for comparison. For the purpose of this study, costs were defined as reimbursements paid by the insurer and adjusted hospital charges using the cost-to-charge ratio. Studies which focused solely on overall health care costs of cancer care (that is, lacking itemized costs for palliative care) were excluded. When two or more articles reported on the same cohort, only the most recent findings were included. We limited our review to studies related to cancer diagnosis only because of the unique palliative care needs of cancer patients and differences between cost of care for cancer and non-cancer patients. We excluded studies on end-of-life care/hospice care unless the palliative care was included in the original study and the detailed costs and health care outcomes of palliative care were clearly reported. We included studies that reported palliative care cost associated with multiple diseases, if one of the diagnoses was cancer and the cost outcomes were stratified by type of disease. Included studies had to be empirical studies, in English language only, and published in the last 10 years, i.e., 2008–2018. We limited our review to the last 10 years to summarize the most recent evidence on the topic.

Study selection

Two out of three reviewers (SY, IH, JH) independently screened study titles and abstracts identified from the literature search and assessed their eligibility for inclusion in the review. The full text of studies selected from abstract review were then independently reviewed by two reviewers (SY, IH) and assessed from inclusion based on the eligibility criteria. In case of disagreements, a third reviewer (JH) assessed the abstract or full text for inclusion.

Data acquisition

We used MS-Excel to create a matrix using the PICOTTS (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes, Type, Timing, Settings) framework [32] for systematically reviewing the full texts. Two reviewers (SY, IH) independently extracted the following data for each study: author, year of publication, study design (RCT, retrospective, prospective cohort, quasi-experimental), country, year of data, study location (state, city), sample size, participants type (patients, caregiver), participant age, participant cancer type, participant cancer stage, participant race, palliative care setting (inpatient, outpatient, home, other), outcome (overall survival [OS], cancer-specific survival [CSS], quality of life [QoL], perspective (patient, provider, societal, payer), type of palliative care (consultation, radiation), timing of palliative care (early, late), comparison arm (if any), data source for costs, type of analysis for cost (nonparametric, statistical model), variable controlled for cost analysis, key results on costs, and key results on clinical outcomes. We assessed the quality of studies using evaluation criteria of 31 indicators compiled by Smith and colleagues [33]. Discrepancies among independent reviewers were resolved through discussions with senior authors. We assessed the quality of included studies using the CHEERS checklist [34] that provides consolidated assessment standards for studies reporting health economic evaluation. The results of which are reported in the Supplemental material.

Results

Literature search

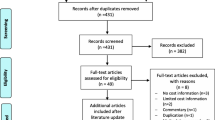

The PRISMA flow chart of the search and retrieval process is shown in Fig. 1. Within databases, 1134 studies were identified (231 PubMed, 667 Web of Science, 173 CINAHL, 42 ABI/INFORM, 10 Health Business, 39 Cochrane Library, 11 ProQuest, and additional 395 from tracking backward and forward references). We removed 128 duplicate articles after merging the citations from all databases. Screening of article titles and abstracts resulted in 72 potentially eligible studies. Full texts of these studies were retrieved and reviewed for inclusion. Finally, 56 potentially eligible studies were excluded, leaving 16 studies for inclusion.

Study characteristics

The studies included differed in study designs, study settings, study populations, and interventions (Tables 1 and 2). Of the 16 selected studies, 13 were retrospective cohort studies, two were secondary analysis of a randomized control trial, and one used prospective observational design. Most of these studies were conducted at single center, except three studies which were conducted at multiple centers. The studies covered a range of palliative care programs including inpatient, outpatient, and home-based care. All the studies had participants aged > 18 years except one study which included only children between the ages of 1 and 21 years.

Cost of palliative care

Data types and sources

To estimate the cost of palliative care, nine studies used the payer’s reimbursement amount. This included five from Medicare, two from health system claims data, one from the Optum research database (included claims information from a large US health plan that offered both commercial and Medicare insurance), one from the National Inpatient Sample dataset. The remaining seven studies used data collected by health care providers in hospital systems like the electronic medical record (EMR), billing, and cost accounting databases.

Palliative care delivery models

Eight studies were based on inpatient palliative care services, four had both inpatient and outpatient palliative care services, two estimated the cost of home-/hospice-based palliative care along with inpatient and outpatient care, and two included only home-based palliative care services. Studies used various definitions of palliative care and provided limited descriptions about the components of palliative care services/program.

Healthcare cost estimates

In 13 out of the 16 studies, the cost associated with palliative care for cancer patients was found to be significantly lower than that for the comparison group [7, 9, 12, 13, 18, 24, 26, 27, 35,36,37, 39], while two studies reported no statistically significant differences in the cost of care [8, 20]. Only one study reported that the patients who received palliative consults incurred significantly higher cost of care in the last 30 days of life compared to patients who did not receive palliative care consults ($1436.8 vs. $1060.7) [28]. However, this difference was not observed for the cost of care incurred in the intensive care unit (ICU) in the last 30 days of life. There was substantial evidence for the positive effect of palliative care in hospitalization cost savings per patient and outpatient costs in the last month of life. Eight studies attributed the reduction in cost to the decrease in the number of admissions, ER visits, inpatient, and ICU length-of-stay in the final months of life [8, 15,16,17,18,19,20,21].

Inpatient cost

The inpatient cost savings ranged from $1285–$28,270 [9, 26]. Lowery and colleagues reported cost savings of $1285 per patient associated with early palliative care compared to routine care. According to their study, early palliative care also had an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of $50,000/QALY (quality-adjusted life year) [9]. Ruck and colleagues reported a statistically significant lower median cost of hospitalization for patients who received inpatient palliative care compared to those who did not receive palliative care ($36,857 vs. $65,127) for all cancer types with the exception of male genitourinary cancer [26]. Only two studies reported no statistically significant difference in hospitalization costs for palliative care patients [8, 20]. Colligan and colleagues reported that cost did not decrease significantly for patients receiving palliative care relative to the comparison group. The authors explained this could be due to the small sample size, as they observed increasingly lower costs per patient in the last 30, 90, and 180 days of life [8].

Outpatient cost

Only two studies reported outpatient cost savings separately from inpatient cost savings [7, 24]. The outpatient savings were in the range of $1000 to $1491 [7, 24]. In the study conducted by Blackhall and colleagues, the cost of care for the palliative care group was significantly lower than that of the control group in the last month of life ($1000 vs. $2000) [24]. Scibetta and colleagues reported an average direct outpatient cost of $11,549 for the last 6 months of life in patients who received early palliative care, which was lower than $13,040 in patients who received late palliative care [7].

Outpatient and inpatient cost

Four studies incorporated both inpatient and outpatient services in their palliative care programs. Three of the four studies reported a reduction in both outpatient costs and inpatient costs. The total cost savings achieved ranged from $1000 to $5198 [7, 13, 24].

Ancillary cost

Two studies reported a significant reduction in laboratory costs associated with palliative care use regardless of the timing of palliative care [27, 38]. The magnitude of this difference was greater for palliative care consults that occurred within 2 days of admission [27] and for patients who were discharged alive [38]. Both studies also found a significant reduction in pharmacy costs following palliative care consultation.

Payer and provider cost

All studies but one [20] that estimated cost savings from the provider perspective showed statistically significant savings associated with palliative care, ranging from $1312 to $20,719 [7, 12, 18, 24, 27, 35,36,37]. Of the studies that reported findings from a payer perspective, four out of six studies reported statistically significant cost savings in the range of $1285 to $28,270 [9, 13, 26, 39]. One of the remaining two studies found the differences in cost following palliative care was not statistically significant [8]. Only one study reported a significantly higher cost associated with palliative care [28].

Home/hospice, inpatient, and outpatient

Two studies reported findings from a comprehensive palliative care program in which the services included home/hospice, as well as outpatient and inpatient palliative care services. Both studies that included all three modalities in their palliative care program reported a reduction in hospital charges ranging from $117 to $400 per day [12, 18]. Greer et al. found that early palliative care group was associated with a cost-effectiveness ratio of $41,938/life year saved as compared to the standard care group [12].

Home-based

Out of the 16 studies, one study measured the cost of a home-based palliative care program. The net saving of palliative care use was $4258 per participant per month in total hospital cost. There was no significant difference in non-hospital costs [35].

Timing of palliative care

Twelve studies focused on the cost differences between providing palliative care and usual care [8, 13, 18, 20, 24, 26, 28, 35,36,37, 39], while the other four studies focused on the cost differences between early and late palliative care [7, 9, 12, 27]. The definition of early palliative care was inconsistent across the studies. Lowery and colleagues defined early palliative care as outpatient palliative care that was initiated at the time of diagnosis. They reported savings of $1285 attributable to early palliative care compared to routine care [9]. Greer et al. reported cost savings of $2527 for patients who underwent early palliative care as compared with those who did not [12]. In their study sample, patient assigned to the early palliative care group met with a palliative care physician or advance practice nurse within 3 weeks of enrollment. May et al. reported cost reductions of 14% and 24% among those who received early palliative care consultations, i.e., within 6 days and 2 days, respectively, of admissions as compared to the no-intervention group [27]. Scibetta et al. defined early palliative care users as patients who received outpatient palliative care at least 90 days prior to death and found the cost was $5198 lower than those who used palliative care late—within the last 90 days of life [7].

Type of cancer

Cancer type was specified in 10 studies. Six studies restricted their analyses to only one cancer type and the remaining four studies included patients diagnosed with multiple cancer types. Studies that analyzed the costs for only one cancer type included pancreatic cancer, bone cancer, lung cancer, renal cancer, ovarian cancer, and head and neck cancer. Studies that analyzed the costs for multiple cancer types included breast, lung, colorectal, head or neck, gastrointestinal, thoracic, male and female genitourinary, brain, endocrine, bone, pancreatic, laryngeal, throat, nasopharyngeal, esophageal, gastric, gallbladder, bile duct, liver, hepatic, ovarian, kidney, endometrial, uterine, cervical, prostate cancers, lymphoma, melanoma, multiple myeloma, mesothelioma, and glioblastoma multiform.

Health care outcomes

The health care outcomes measured in the studies were the number of hospitalizations, length of hospitalizations, number of ICU admissions, length of stay in the ICU, rate of chemotherapy use, quality of life, ED visits, mortality, and 30-day readmission rates. Use of palliative care was found to be associated with improvements in the quality of life [6,7,8,9, 12], similar or extended survival [6, 12, 13], fewer patients with depressive symptoms [6, 12], reduction in length of hospital stay, less inpatient admissions, and less number of emergency department and physician office visits [8, 15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. It is important to note that none of the studies reported any adverse effects of palliative care on clinical outcomes.

Discussion

Our systematic review aimed to identify cost associated with palliative care for patients diagnosed with cancer in different delivery settings in the US. Overall, most studies found that there were cost savings associated with palliative care program for patients suffering from advanced cancer. Similarly, this review found that palliative care in all delivery settings lead to reduced healthcare utilization and thus reduced cost. Our findings align with previous reviews of economic impact of palliative care, suggesting that palliative care is associated with reduced healthcare cost and improved care for patients with serious illness [21]. However, a few studies reviewed here reported that palliative care was not associated with reduced healthcare utilization or cost. This inconsistency in our findings can be explained in many possible ways [28]. First, for the studied cohort, one-third of the palliative care consults happened in the last week of life. Other studies that reported economic benefit associated with palliative care stressed on the timing of palliative care. Early palliative care interventions were found to be associated with more cost savings than late palliative care interventions [7, 9, 12, 27]. Moreover, their analysis suggested that sicker patients were getting the referrals and also very late in the disease course which may have limited the impact of palliative care cost-benefit.

Our systematic review found several gaps in the available literature. First, none of the studies compared the costs and clinical outcomes of palliative care across multiple palliative care delivery models, reflecting that the cost and clinical effectiveness of alternative delivery methods of palliative care have not been studied well. Further, many studies had limited sample size and were limited to a single institution, which resulted in findings which were not statistically significant or had wide confidence intervals [8, 36].

Although most of these studies reported that palliative care in cancer patients provides cost savings to the payers and providers, direct comparison of cost associated with palliative care across studies is problematic due to differences in cancer types, palliative care services, and reimbursement rates for palliative care by payers. There were also considerable inconsistencies in terms of start time and duration of palliative care services as well as in the type of palliative care offered. The palliative care services in some studies were limited to outpatient or inpatient consultation, and in others, they also included caregiver support, advanced health planning, patient and family education, psychosocial and spiritual support, pain and non-pain symptom management, and palliative radiotherapy.

Data on the cost associated with palliative care to the patient and caregiver are still needed. None of the studies in our review provide any findings on the cost of care to the patient, family, or caregiver: all costs were estimated from either the payer’s or provider’s perspective. Future studies need to widen the perspective on examining the cost associated with palliative care to incorporate costs related to patient, family, caregiver, and society, such as out-of-pocket expenditure, opportunity cost of time, and travel cost. Nijboer and colleagues found that finances were one of the five dimensions of care giving in palliative care, citing a negative effect on the caregiver experience in end-stage cancer patients [40]. Without taking into account all other costs, the true magnitude of cost savings from palliative care programs may be underestimated.

Studying the costs of palliative care in isolation without considering quality of care will render the findings less meaningful. Many of the studies included in this review demonstrated the impact of palliative care on clinical outcomes, and none reported any negative impact. The health care outcomes commonly measured in these studies were the number of hospitalizations, length of hospitalizations, number of ICU admissions, length of stay in the ICU, rate of chemotherapy use, quality of life, ED visits, mortality, and 30-day readmissions. Patients in the palliative care group were less likely to be admitted to the hospital in the last month of life [7, 24, 35], had shorter lengths of hospitalizations [27, 28, 35, 36], and had a lower in-hospital mortality rates [7, 24, 35]. Palliative care patients also had higher odds of receiving hospice referral [18, 24] and better quality of life when compared to the control group [7, 9] though similar survival rates [13].

Our systematic review has several limitations. First, most of the studies were observational studies and do not provide evidence for a strong causal inference about the cost-saving effect of palliative care for patients diagnosed with cancer. Second, there were heterogeneities in the way costs measures were analyzed in the studies, rendering it impractical to derive an average effect size. Because of which, we qualitatively summarized the findings of the studies included in this review. Third, we gathered evidence related to costs associated with palliative care for cancer patients in the context of US healthcare and the findings may not be valid for other countries. Fourth, we excluded studies that did not report detailed costs of palliative care including how the costs were estimated. We feel the study with a sole number of costs of palliative care with no other details provides limited value to link the expenses and outcomes. Our study aimed to include economic outcomes of comprehensive palliative care services given to cancer patients; therefore, the literature reporting only single intervention, such as using radiation therapy to manage the cancer pain, was not included.

Conclusion

In summary, our study found an association between palliative care in cancer patients and lower health care costs. However, remarkable differences in cost exist in hospital-based and outpatient-based delivery models for palliative care. The cost savings of the other palliative care delivery models are still largely unknown. Given the current paucity of studies producing comparable conclusions, it is difficult to present any evidence on which palliative care delivery model represents the most cost-effective means of delivering palliative care.

References

Hughes MT, Smith TJ (2014) The growth of palliative care in the United States. Annu Rev Public Health 35(1):459–475. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182406

Dumanovsky T, Augustin R, Rogers M, Lettang K, Meier DE, Morrison RS (2016) The growth of palliative care in U.S. hospitals: a status report. J Palliat Med 19(1):8–15. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2015.0351

Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, Alesi ER, Balboni TA, Basch EM, Firn JI, Paice JA, Peppercorn JM, Phillips T, Stovall EL. Integration of Palliative Care Into Standard Oncology Care: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 35(1):96

Sepúlveda C, Marlin A, Yoshida T, Ullrich A 2002 Palliative care: the World Health Organization's global perspective. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 24(2):91–6

Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, Hannon B, Leighl N, Oza A, Moore M, Rydall A, Rodin G, Tannock I, Donner A, Lo C (2014) Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 383(9930):1721–1730. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62416-2

Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, Dahlin CM, Blinderman CD, Jacobsen J, Pirl WF, Billings JA, Lynch TJ (2010) Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 363(8):733–742. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1000678

Scibetta C, Kerr K, Mcguire J, Rabow MW (2016) The costs of waiting: implications of the timing of palliative care consultation among a cohort of decedents at a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med 19(1):69–75. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2015.0119

Colligan EM, Ewald E, Ruiz S, Spafford M, Cross-Barnet C, Parashuram S (2017) Innovative oncology care models improve end-of-life quality, reduce utilization and spending. Health Aff 36(3):433–440. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1303

Lowery WJ, Lowery AW, Barnett JC, Lopez-Acevedo M, Lee PS, Secord AA, Havrilesky L (2013) Cost-effectiveness of early palliative care intervention in recurrent platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 130(3):426–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.YGYNO.2013.06.011

Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, Balan S, Brokaw FC, Seville J, Hull JG, Li Z, Tosteson TD, Byock IR, Ahles TA (2009) Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer. JAMA. 302(7):741–749. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.1198

Grudzen CR, Richardson LD, Johnson PN, Hu M, Wang B, Ortiz JM, Kistler EA, Chen A, Morrison RS (2016) Emergency department–initiated palliative care in advanced cancer. JAMA Oncol 2(5):591–598. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.5252

Greer JA, Tramontano AC, McMahon PM et al (2016) Cost analysis of a randomized trial of early palliative care in patients with metastatic nonsmall-cell lung cancer. J Palliat Med 19(8):842–848. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2015.0476

Henk HJ, Chen C, Benedict A, Sullivan J, Teitelbaum A (2013) Retrospective claims analysis of best supportive care costs and survival in a US metastatic renal cell population. Clin Econ Outcomes Res 5:347. https://doi.org/10.2147/CEOR.S45756

Connor SR, Pyenson B, Fitch K, Spence C, Iwasaki K (2007) Comparing hospice and nonhospice patient survival among patients who die within a three-year window. J Pain Symptom Manag 33(3):238–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JPAINSYMMAN.2006.10.010

May P, Garrido MM, Cassel JB, Kelley AS, Meier DE, Normand C, Smith TJ, Morrison RS (2017) Cost analysis of a prospective multi-site cohort study of palliative care consultation teams for adults with advanced cancer: where do cost-savings come from? Palliat Med 31(4):378–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216317690098

May P, Garrido MM, Cassel JB, Kelley AS, Meier DE, Normand C, Stefanis L, Smith TJ, Morrison RS (2016) Palliative care teams’ cost-saving effect is larger for cancer patients with higher numbers of comorbidities. Health Aff 35(1):44–53. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0752

Gade G, Venohr I, Conner D, McGrady K, Beane J, Richardson RH, Williams MP, Liberson M, Blum M, Penna RD (2008) Impact of an inpatient palliative care team: a randomized controlled trial. J Palliat Med 11(2):180–190. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2007.0055

Cassel JB, Webb-Wright J, Holmes J, Lyckholm L, Smith TJ (2010) Clinical and financial impact of a palliative care program at a small rural hospital. J Palliat Med 13(11):1339–1343. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2010.0155

Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, Smith TJ (2017) Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: ASCO clinical practice guideline update summary. J Oncol Pract 13(2):119–121

Postier A, Chrastek J, Nugent S, Osenga K, Friedrichsdorf SJ (2014) Exposure to home-based pediatric palliative and hospice care and its impact on hospital and emergency care charges at a single institution. J Palliat Med 17(2):183–188. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2013.0287

May P, Normand C, Morrison RS (2014) Economic impact of hospital inpatient palliative care consultation: review of current evidence and directions for future research. J Palliat Med 17(9):1054–1063. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2013.0594

Temel JS, Greer JA, Admane S, Gallagher ER, Jackson VA, Lynch TJ, Lennes IT, Dahlin CM, Pirl WF (2011) Longitudinal perceptions of prognosis and goals of therapy in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a randomized study of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol 29(17):2319–2326. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.32.4459

Elsayem A, Swint K, Fisch MJ, Palmer JL, Reddy S, Walker P, Zhukovsky D, Knight P, Bruera E (2004) Palliative care inpatient service in a comprehensive cancer center: clinical and financial outcomes. J Clin Oncol 22(10):2008–2014. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2004.11.003

Blackhall LJ, Read P, Stukenborg G, Dillon P, Barclay J, Romano A, Harrison J (2016) CARE track for advanced cancer: impact and timing of an outpatient palliative care clinic. J Palliat Med 19(1):57–63. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2015.0272

Pirl W (2011) Effect of early palliative care on chemotherapy use and end-of-life care in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer addressing psychological distress in parents of children with cancer view project building resiliency in a Palliative Care Team View project. Artic J Clin Oncol 30:394–400. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.35.7996

Ruck JM, Canner JK, Smith TJ, Johnston FM (2018) Use of inpatient palliative care by type of malignancy. J Palliat Med 21(9):1300–1307. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2018.0003

May P, Garrido MM, Cassel JB, Kelley AS, Meier DE, Normand C, Smith TJ, Stefanis L, Morrison RS (2015) Prospective cohort study of hospital palliative care teams for inpatients with advanced cancer: earlier consultation is associated with larger cost-saving effect. J Clin Oncol 33(25):2745–2752. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.60.2334

Bhulani N, Gupta A, Gao A et al (2018) Palliative care and end-of-life health care utilization in elderly patients with pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Oncol 9(3):495–502. https://doi.org/10.21037/jgo.2018.03.08

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 151(4):264–269. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

Richardson WS, Wilson MC, Nishikawa J, Hayward RS (1995) The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. ACP J Club 123(3). https://doi.org/10.7326/ACPJC-1995-123-3-A12

Bekelman JE, Halpern SD, Blankart CR, Bynum JP, Cohen J, Fowler R, Kaasa S, Kwietniewski L, Melberg HO, Onwuteaka-Philipsen B, Oosterveld-Vlug M, Pring A, Schreyögg J, Ulrich CM, Verne J, Wunsch H, Emanuel EJ, for the International Consortium for End-of-Life Research (ICELR) (2016) Comparison of site of death, health care utilization, and hospital expenditures for patients dying with cancer in 7 developed countries. JAMA 315(3):272–283. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.18603

Schardt C, Adams MB, Owens T, Keitz S, Fontelo P (2007) Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-7-16

Smith S, Brick A, O’Hara S, Normand C (2014) Evidence on the cost and cost-effectiveness of palliative care: a literature review. Palliat Med 28(2):130–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216313493466

Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, Carswell C, Moher D, Greenberg D, Augustovski F, Briggs AH, Mauskopf J, Loder E, CHEERS Task Force (2013) Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards (cheers) statement. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 29(2):117–122. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462313000160

Brian Cassel J, Kerr KM, McClish DK et al (2016) Effect of a home-based palliative care program on healthcare use and costs. J Am Geriatr Soc 64(11):2288–2295. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14354

Chang S, May P, Goldstein NE, Wisnivesky J, Ricks D, Fuld D, Aldridge M, Rosenzweig K, Morrison RS, Dharmarajan KV (2018) A palliative radiation oncology consult service reduces total costs during hospitalization. J Pain Symptom Manag 55(6):1452–1458. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JPAINSYMMAN.2018.03.005

McCarthy IM, Robinson C, Huq S, Philastre M, Fine RL (2015) Cost savings from palliative care teams and guidance for a financially viable palliative care program. Health Serv Res 50(1):217–236. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12203

Morrison RS, Penrod JD, Cassel JB, Caust-Ellenbogen M, Litke A, Spragens L, Meier DE, Palliative Care Leadership Centers' Outcomes Group (2008) Cost savings associated with US hospital palliative care consultation programs. Arch Intern Med 168(16):1783–1790. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.168.16.1783

Mulvey CL, Smith TJ, Gourin CG (2016) Use of inpatient palliative care services in patients with metastatic incurable head and neck cancer. Head Neck 38(3):355–363. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.23895

Nijboer C, Triemstra M, Tempelaar R, Sanderman R, van den Bos GA (1999) Measuring both negative and positive reactions to giving care to cancer patients: psychometric qualities of the Caregiver Reaction Assessment (CRA). Soc Sci Med 48(9):1259–1269. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00426-2

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yadav, S., Heller, I.W., Schaefer, N. et al. The health care cost of palliative care for cancer patients: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 28, 4561–4573 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05512-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05512-y