Abstract

Purpose

Despite survival rates greater than 90%, treatment for paediatric acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) remains challenging for families. The early post-treatment phase is an especially unique time of adjustment. The primary aim of this review was to identify and synthesise research on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) for patients up to five years post-treatment. The secondary aim was to identify if theorised risk/resistance model factors could explain any variance in reported HRQoL.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review using the PRISMA guidelines across five databases: Embase, Medline, Psychinfo, Pubmed, and Cochrane. Only studies examining HRQoL up to five years post-treatment were included. Studies were excluded if they covered periods greater than five years post-treatment or did not differentiate between patients with ALL and other cancers. After assessing the quality of each study sample size, patient characteristics, HRQoL outcomes and HRQoL correlates were extracted and summarised.

Results

A total of 14 studies representing 1254 paediatric patients, aged 2–18 years, were found. HRQoL findings were mixed, dependent on time since completion and comparison group. Patient HRQoL was mostly lower compared to normative data, whilst higher compared to healthy control groups, patients on treatment, and patients with other types of cancers. Lower HRQoL was also found to be associated with demographic (age and sex), family dysfunction, and treatment-related factors.

Conclusions

Completing treatment signalled a significant improvement in HRQoL for patients compared to being on treatment. Overall, however, HRQoL was still significantly lower than the population during the early post-treatment period.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in children, with survival rates now exceeding 90% [1, 2]. Paediatric cancer differs from many other paediatric health conditions in that ongoing monitoring is recommended following curative treatment [3, 4]. From a psychosocial perspective, diagnosis and treatment of ALL have been shown to lead to adjustment difficulties for not only the patients but also their families [5,6,7]. Upon completing treatment, patients and their families attempt to re-adjust and return to pre-diagnosis life. Adjustment, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO) definition, is more than just the absence of disease and should encompass physical, mental, and social well-being [8]. Numerous instruments for measuring adjustment exist based on differing interpretations of this definition; however, most research that covers paediatric populations operationalises adjustment as health-related quality of life (HRQoL) incorporating the influence of illness and treatment across multiple domains including the following: physical health, psychological state, levels of independence, social relationships, and environmental features [9]. In addition, patient self-reported HRQoL is often considered the standard in paediatric cancer populations; however, parent proxy reports of HRQoL have been validated and used where patients are too ill and physically unable to complete instruments [9]. Previous reviews of patients on treatment for ALL, as well as long-term survivors of ALL, have found that a large percentage report lower HRQoL during treatment and a subset continue to report lower HRQoL many years following treatment completion [10,11,12,13]. Despite recent improvement in survival rates, there has generally been little focus on HRQoL during the immediate period following treatment completion or on identifying non treatment-related potential predictors of long-term HRQoL.

Following the completion of treatment for ALL, regular surveillance is usually recommended for approximately five years, a period when interactions with health services can be markedly reduced when compared to interactions during treatment. Previous reviews on the adjustment of patients following treatment for ALL typically include studies of long-term outcomes, i.e. five or more years, and up to 30 years, post-treatment completion [11, 13]. Findings have been mixed, with some studies in these reviews reporting lower HRQoL whilst others have reported no difference between patients and controls suggesting possible changes in adjustment over time [11, 13]. In addition, studies that consider HRQoL during treatment are mostly cross-sectional and tend to rely on parent proxy reports given the age and capacity of the patients, whilst studies that focus on long-term outcomes often shift to patient self-reports of HRQoL [10,11,12,13]. Previous reviews have also lacked a theoretical framework to guide interpretation of the variance in HRQoL reported post-treatment. As a result, relatively little is known about the general adjustment of patients during the period between treatment completion and the initial years of surveillance. It is also difficult to extrapolate the findings of the current literature for patients who have completed treatment for ALL using modern regimens with reduced toxicity and improved survival rates [14].

Patient and family experiences in the first few years of surveillance after treatment completion may be markedly different from the active treatment phase and the longer-term survivorship period. During post-treatment surveillance, the available literature shows that parents of patients can have mixed feelings of gratefulness and uncertainty, along with the pervasive fear of their child relapsing, whilst patients themselves report relief as they no longer face the physical and psychological demands of treatment [15,16,17]. In order to understand these differing experiences of patients and their parents across this period, the risk/resistance model provides a theoretical framework for investigating and understanding how the adjustment of one significantly ill family member can affect the individual as well as other members of the family [18]. The underlying assumptions of the risk/resistance model are that risk factors (e.g. physical illness and associated parental stress), intrapersonal factors (e.g. optimism), social-ecological factors (e.g. family functioning), and stress processing factors (e.g. coping styles) interrelate to influence individual adjustment when a family member is suffering from a health condition [18]. As such, this review aims to (i) identify and synthesise cross-sectional and longitudinal research on parent proxy and self-reported adjustment, operationalised as HRQoL, following treatment for ALL solely within the first five-year surveillance period, (ii) compare the reported HRQoL of this cohort with normative data or controls if included, and (iii) identify if the theorised risk or resistance factors are associated with HRQoL in order to guide future interventions.

Methods

We conducted a systematic literature review targeting studies that examined the HRQoL of survivors of paediatric ALL using the PRISMA guidelines across five databases: Embase, Medline, Psychinfo, Pubmed, and Cochrane [19]. The initial search was completed on 20 October 2017 and a repeat search completed on 10 February 2019. We used the following search terms with limits to only include studies published after 2000: ((acute or (precursor adj cell)) adj1 (lymphoblastic or lymphocyt* or lymphoid or lymphatic) adj1 (leuk?emia or lymphoma)) AND ((quality adj2 life) or qol or hrqol) AND (newborn* or baby or babies or neonat* or infan* or toddler* or pre-schooler* or preschooler* or kindergarten or boy or boys or girl or girls or child or children or childhood or adolescen* or pediatric* or paediatric* or youth* or teen or teens or teenage*). A follow-up search of the reference lists of the included studies was also completed. Non-peer reviewed grey literature was not included in this review. Studies published prior to 2000, a period when radiation therapy was also regularly used during treatment, were not included in this review to ensure that we primarily covered patients treated using modern regimens likely to only involve chemotherapy [20, 21].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We used the following inclusion criteria to screen studies: (i) patients diagnosed with ALL aged up to 18 years at the time of diagnosis; (ii) studies examining HRQoL using a validated instrument with adequate reliability and validity, primarily based on the list of instruments thoroughly reviewed by Palermo et al. [9]; (iii) studies solely covering the period up to five years post-treatment completion for ALL; and (iv) studies published in English. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) studies combining the HRQoL data of patients with ALL with the HRQoL data of patients with other types of paediatric cancer and (ii) studies combining the HRQoL data of patients with ALL for both periods less than five years post-treatment completion and periods greater than five years post-treatment completion.

Screen and data extraction

Independent reviewers (AG and BD) screened the titles and abstracts of the search results. Reviewers obtained full texts of studies that potentially met the inclusion criteria. These were then assessed by the reviewers to determine inclusion, with a third independent reviewer (MM) consulted if consensus could not be reached. Data extraction of the final studies, which included study type, sample size, patient characteristics, HRQoL outcomes, and HRQoL correlates was completed by the reviewers (AG and BD) with results compared for the first 25% of studies to verify the data extraction procedure.

Quality assessment

We completed quality assessments for each study using the instrument developed by Kmet et al. [22]. This instrument has been previously used in similar reviews [10, 11] and adequately covers fundamental aspects of study designs, methods, measurements, outcomes, and bias using 14 items, rated on the degree to which they meet the criteria (2 = “Yes”, 1 = “Partial”, 0 = “No” or N/A) [22]. A total score is then calculated and adjusted for the number of “N/A” responses. Higher scores equate to higher quality studies. Two independent reviewers (AG and BD) assessed the quality of the first 25% of studies together, after which the remaining studies were assessed separately with an inter-rater reliability of > 90% (see Online Resource 1).

Results

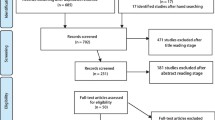

Both the initial and updated searches returned a combination of 994 studies after the removal of duplicates. Titles and abstracts were screened leading to the exclusion of a further 882 studies. The full texts of the remaining 112 studies were reviewed, and studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded (see Fig. 1). An additional five identified studies were included after a hand search, resulting in a final 14 studies, representing 1254 patients being identified as eligible for data extraction. No qualitative studies were included due to the requirement that HRQoL be measured using a validated instrument. No studies were excluded due to the instrument used, as all included studies utilised reliable and valid instruments. A summary of the data extracted from these studies is presented in Table 1.

The majority of studies rated well in terms of the quality assessment (M = .85, SD = .10, range = 0.68–0.95). All studies appeared to report their results adequately with no missing data. Lower quality ratings were primarily due to relatively small sample sizes [23, 27,28,29, 31, 32, 34]. This was expected given the overall incidence rates of ALL in the population. Kobayashi et al., for example, had a total sample of 35 participants; however, only data from a subset of six participants was used in this review as this was the total number of participants in the post-treatment phase [28]. Studies were also rated lower for not considering or controlling for potentially confounding variables, such as type or duration of treatment (see Supplementary Table S1). The four lowest rated studies were due to a combination of the abovementioned factors [25, 27, 28, 34]. The data reported in studies with lower quality ratings were not excluded given the overall small number of identified studies that met the selection criteria. The findings of these lower quality studies, however, were interpreted cautiously.

With regard to measurement instruments, six studies defined and measured HRQoL as outlined in the Paediatric Quality of Life Inventory using self-report or parent proxy forms [24, 28,29,30, 32, 35]. The remaining studies used a range of different instruments that broadly covered adjustment, operationalised as quality of life, including the Health Utilities Index and the Child Health Questionnaire, amongst others [16, 23, 25,26,27, 31, 33, 34]. Nine studies compared self-report and parent proxy responses with normative data [16, 23, 24, 26, 27, 29,30,31, 34]. Five studies relied solely on parent proxy reports of their child’s HRQoL post-treatment completion [24, 29, 30, 34, 35]. Countries of origin were diverse, with seven studies using instruments in a language other than English [23, 25, 27, 28, 31, 32, 34]. Four studies examined HRQoL immediately following treatment completion [23, 24, 31, 35], with the remaining studies covering reported HRQoL between two months and five years post-treatment completion [16, 25,26,27,28,29,30, 32,33,34]. Six of the included 14 studies tracked the HRQoL of patients longitudinally [23, 24, 26, 30, 31, 35] either from diagnosis onwards or treatment completion onwards. Given these reasons, the extracted data was not deemed suitable for quantitative analysis given the heterogeneity of methodology, and differing reports (parent proxy versus self-report) and measurement instruments.

HRQoL post-treatment completion

The findings of this review, both within and between studies, were mixed. The same study could report both higher and lower HRQoL depending on whether comparing to normative data, controls, patients on treatment for ALL, or patients with other types of cancers, and also depending on age, time following treatment completion and parent proxy or self-report. Where higher HRQoL scores were reported, this indicated better or improved HRQoL, whilst lower HRQoL scores suggested difficulties or challenges with HRQoL, but not necessarily clinical impairments.

Seven of the 14 studies reported higher overall HRQoL for patients post ALL treatment completion when patients were compared to normative data, controls, patients on treatment for ALL, and patients with other types of cancers [25, 27,28,29,30,31, 33]. Four of the 14 studies reported no difference in overall HRQoL dependent upon which group patients were being compared to [26, 28, 29, 34]. For example, patients completing treatment for ALL in one study showed no difference in HRQoL when compared to normative data [26]. Significantly lower overall HRQoL was reported by six of the 14 studies, again depending on which group that the patients completing treatment for ALL were being compared to; normative data, controls, patients on treatment for ALL, and patients with other types of cancers [16, 23,24,25, 27, 31, 32]. One study did not include an overall measure of HRQoL, reporting on only three of the subscales (physical, emotional, and social functioning) and finding all three to be lower than normative data at treatment completion [35].

Regarding correlates of HRQoL, three of the 14 studies found that patients who were younger or female were more likely to report lower overall HRQoL [29, 30, 34]. Furthermore, Stam et al. found that parents of patients who were less than 8 years old reported that their children had more problems with sleep, behaviour, and appetite, as well as lower HRQoL when compared to normative data [16].

In terms of the specific domains that comprise HRQoL, studies included in this review reported on overall HRQoL as well as at least two of the three domains of adjustment used in the WHO definition (physical, emotional, or social) dependent upon the instrument used [8]. With regard to statistically significant differences reported on individual HRQoL domains, nine of the 14 studies specifically reported lower physical functioning at some point in the post-treatment completion period, mostly nearer to treatment completion [16, 23, 24, 27, 29,30,31,32, 35]. This appeared to improve over time, with Meeske et al. reporting significantly higher physical functioning in a small sample of patients that were more than 12 months off treatment when compared to patients less than 12 months off treatment [29]. In addition, seven studies examining either emotional, social, or school/environmental functioning reported these domains as significantly lower depending on the instrument used and comparison group [16, 23,24,25, 31, 32, 35], whilst three found no difference in these domains, also depending on comparison groups [26, 28, 29, 34]. Only four of the 14 studies reported significantly higher emotional, social, or school/environmental functioning post-treatment completion when compared to controls, normative data, and patients with different types of cancers [23, 24, 30, 32].

Seven of the 14 studies included both parent proxy and self-reports [16, 23, 25,26,27,28, 31], with two of these studies finding that parents reported their child’s overall HRQoL to be significantly lower than parents of controls [27, 31], whilst another study found no difference [23]. However, in these same studies, self-reported overall HRQoL was higher than the corresponding parent proxy reports across the separate domains of HRQoL [27, 31]. Of the four studies that only included parent proxy reports of their child’s HRQoL post-treatment completion, results were mixed, with two showing no difference in overall HRQoL [29, 34], and two showing significantly lower overall HRQoL, and specific domains of HRQoL, when compared to normative data [24, 35].

HRQoL over time

Across the four studies examining overall HRQoL or domains of HRQoL at treatment completion, patients who had completed treatment appeared more likely to self-report higher HRQoL than those patients still on treatment [23, 24, 31, 35]. The patients in these four studies, however, still displayed significantly lower HRQoL when compared to normative data, as reported via parent proxy (see Fig. 2) [23, 24, 31, 35]. For the three studies that covered six months or less post-treatment, patients were found to be either no different to control groups or more likely to self-report higher HRQoL than normative data [16, 28, 30]. For the same period, parent proxy reports continued to be significantly lower than normative data or patients on treatment [16, 28, 30]. The remaining seven out of 14 studies covering the period 12 to 60 months post-treatment showed that both self-reports and parent proxies were mostly higher in terms of HRQoL when compared to normative data, control groups, or patients on treatment [25,26,27, 29, 32,33,34].

Risk/resistance factors

With regard to patient-related risk factors, Mitchell et al. found adverse events such as seizures or impaired limb functioning during treatment, predicted lower overall HRQoL in patients three months post ALL treatment completion [30]. Gordijn et al. reported that parent ratings of their child’s impaired sleep and increased fatigue correlated with lower physical functioning during the post-treatment period [27]. Inversely, the patients themselves reported less sleep problems as well as improved social functioning in the same study [27]. Two studies reported correlations between the type of treatment (e.g. radiotherapy) and lower physical functioning during the post-treatment period [23, 32]. One study examined the social-ecological resistance factor of family functioning, finding that after controlling for age and sex, family dysfunction predicted poor emotional functioning at treatment completion [35]. Intrapersonal and stress processing resistance factors were not examined in any of the 14 studies included in this review.

Discussion

The overall aims of this review were to summarise the literature available on the adjustment, operationalised as HRQoL, of paediatric patients in the first five years post-treatment completion for ALL, as well as examining if theorised risk or resistance factors were associated with adjustment. This review identified and synthesised 14 studies covering this period, finding that patients who had completed ALL treatment reported higher HRQoL or no difference when compared to patients on treatment [23, 26, 29, 31], control groups [28], normative data [26,27,28,29,30, 34], and patients with other types of cancers [33]. A subset of patients were found to have lower HRQoL when compared to normative data shortly after treatment, primarily reported by parent proxy [16, 23, 24, 28, 31, 35]. As theorised by the risk/resistance model, this review also identified that the presence of risk factors, such as treatment-related side effects or child characteristics including poor sleep patterns, were more likely to be associated with poorer quality of life post-treatment completion [16, 30]. Social-ecological resistance factors, such as family dysfunction, were also found to predict domains of HRQoL highlighting the influence of the family environment on the patient [35].

Previous reviews have found that long-term survivors of ALL often report lower HRQoL experienced many years after treatment completion that is usually attributable to adverse late effects, such as secondary cancers, cognitive late effects, fertility issues, psychosocial issues, and higher incidence of psychopathology [10,11,12]. In this review, the improvements across HRQoL domains were found shortly after treatment completion and mainly when patients were compared to those still on treatment [23, 30, 31]. This may simply be attributable to the immediate relief of being “cured” of ALL, marking an important milestone for the patient and their parents as they are no longer undergoing intensive treatment regimens with potential adverse side effects. Despite this, however, most patients still reported lower HRQoL when compared to healthy children shortly after treatment [16, 23, 24, 28, 31, 35]. These patients, despite being free of disease and no longer undergoing treatment, continued to exhibit lower HRQoL similar to the findings of previous reviews that focused on long-term survivorship [10, 11]. HRQoL did, however, appear to improve slightly as time progressed [25, 27, 29, 33], possibly due to improved physical recovering over time, as well as, the fear of relapse subsiding as patients transition to long-term survivorship. HRQoL, therefore, may be influenced by factors relating to the patients and family and not just improved treatment regimens.

Multiple studies found that lower HRQoL was reported via parent proxy and not the patients themselves, suggesting that parents were perceiving treatment completion as a negative experience on behalf of their child [16, 23, 24, 27, 28, 30, 31, 35]. This could be as a result of the significant distress, fatigue, loneliness, and fear of relapse that parents themselves often report following their child’s treatment [17]. The post-treatment period is also characterised by reduced interactions with health services, leaving patients and their parents with diminishing support as they attempt to recover from their cancer experience. Additionally, for patients who have ongoing complications from treatment-related side effects, the period immediately following treatment completion is likely to continue to cause significant distress leading to lower HRQoL.

When considered with respect to the theoretical framework of the risk/resistance model, as expected, the presence of ongoing risk factors, such as treatment-related physical effects or child characteristics including poor sleep patterns and family dysfunction, was more likely to be associated with lower HRQoL post-treatment completion [16, 30, 35]. For families where parents reported child lower HRQoL and the patient themselves did not, one possible explanation could be the presence of intrapersonal resistance factors (e.g. optimism) that mitigate the impact of risk factors (e.g. parental distress or family dysfunction). For example, patients may be more likely to better adjust post-treatment completion if they are optimistic of returning to pre-diagnosis life and have adequate social support, despite ongoing risk factors, such as parental distress or persistent complications of treatment. As the studies included in this review appeared to focus primarily on examining correlating risk factors, future research would benefit from considering intrapersonal and socioecological resistance factors. By identifying resistance factors amenable to intervention, health services will be able to better allocate their limited post-treatment resources to target this group. The early post-treatment period presents the most opportune time to engage patients and their families in useful education programs and targeted interventions. Due to reduced medical requirements but ongoing links with health services, patients and their families could, therefore, be engaged in proactive programs to avert negative long-term outcomes.

Limitations

The sample sizes of studies included in this review were relatively small, attributable to the low incidence rates of ALL and study participation rates. Several studies cited this factor as an important consideration when interpreting results and a potential risk of bias. The inconsistent use of HRQoL instruments, sometimes in multiple languages, also leads to difficulty comparing and generalising results. Studies conducted in different languages may mask important social and cultural differences that influence HRQoL for those patients and their parents. It is also important to note that the majority of studies reporting significantly lower HRQoL tended to be those with lower quality ratings due to smaller sample sizes and inability to control for confounds, such as type and duration of treatment [23, 25 27, 28–29, 31–32, 34]. Different stages of disease risk and different modes of treatments that cause side effects of varying severity may have potentially significant influences on HRQoL post-treatment completion [12]. Where possible, future studies should endeavour to utilise homogenous patient samples whom have undergone similar types of ALL treatment, whilst managing confounds such as incidence of relapse, pre-existing health conditions, and cultural and socio-demographic factors.

Conclusions

This systematic review of 14 studies found that overall HRQoL for patients within the first five years post-treatment completion for ALL was similar to, or higher than, patients on active ALL treatment, normative data, control groups, and patients with other types of cancers [23, 25, 27,28,29,30,31, 33]. A subset of patients were found to have lower HRQoL post-treatment completion when compared to normative data, controls, patients on treatment for ALL, and patients with other types of cancers [16, 23,24,25, 27, 28, 31, 32]. Despite reporting improved overall HRQoL, many patients continued to report lower physical functioning post-treatment completion [16, 23, 24, 27, 29,30,31,32, 35]. Risk factors found to contribute to lower HRQoL (overall and physical functioning) included: age at completion, sex, family dysfunction, type of treatment, and the experience of adverse events during treatment, as theorised by the risk/resistance model [29, 30, 34]. Protective resistance factors, however, were not identified as studies focused more on reporting on HRQoL outcomes, rather than explaining the variance. More research is required to understand this variability in adjustment for the initial period post-treatment completion and to identify potential resistance factors, suggested by the risk/resistance model, that are amenable to intervention in order to better support those patients susceptible to negative long-term outcomes.

Abbreviations

- ALL:

-

Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia

- HRQoL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- PedsQL:

-

Paediatric quality of life inventory

- CHQ:

-

Child health questionnaire

References

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2017) Australian cancer incidence and mortality: acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/bf837c83-d746-44fb-b5cf-ef95079665a6/acute-lymphoblastic-leukaemia.xlsx.aspx. Accessed February 22 2018

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2017) Cancer in Australia 2017. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/3da1f3c2-30f0-4475-8aed-1f19f8e16d48/20066-cancer-2017.pdf.aspx. Accessed February 24 2018

Essig S, Li Q, Chen Y, Hitzler J, Leisenring W, Greenberg M, Sklar C, Hudson MM, Armstrong GT, Krull KR, Neglia JP, Oeffinger KC, Robison LL, Kuehni CE, Yasui Y, Nathan PC (2014) Risk of late effects of treatment in children newly diagnosed with standard-risk acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study cohort. Lancet Oncol 15:841–851. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70265-7

Oeffinger KC, Nathan PC, Kremer L (2010) Challenges after curative treatment for childhood cancer and long-term follow up of survivors. Hematol Oncol Clin N 24:129–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hoc.2009.11.013

Hile S, Erickson SJ, Agee B, Annett RD (2014) Parental stress predicts functional outcome in pediatric cancer survivors. Psychooncology 23:1157–1164. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3543

Myers M, Balsamo L, Lu X et al (2014) A prospective study of anxiety, depression, and behavioral changes in the first year after a diagnosis of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer 120:1417–1425. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28578

Nicolaas SMS, Hoogerbrugge PM, van den Bergh EMM et al (2016) Predicting trajectories of behavioral adjustment in children diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Support Care Cancer 24:4503–4513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3289-9

World Health Organization (1948) Constitution of the World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/governance/eb/who_constitution_en.pdf. Accessed 11 March 2018

Palermo TM, Long AC, Lewandowski AS, Drota D, Quittner AL, Walker LS (2008) Evidence-based assessment of health-related quality of life and functional impairment in pediatric psychology. Pediatr Psychol 33:983–996. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsn038

Fardell JE, Vetsch J, Trahair T, Mateos MK, Grootenhuis MA, Touyz LM, Marshall GM, Wakefield CE (2017) Health-related quality of life of children on treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a systematic review. Pediatr Blood Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.26489

Vetsch J, Wakefield CE, Robertson EG, Trahair TN, Mateos MK, Grootenhuis M, Marshall GM, Cohn RJ, Fardell JE (2018) Health-related quality of life of survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a systematic review. Qual Life Res 27:1431–1443. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1788-5

Savage E, Riordan AO, Hughes M (2009) Quality of life in children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a systematic review. Eur J Oncol Nurs 13:36–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2008.09.001

Lund LW, Schmiegelow K, Rechnitzer C, Johansen C (2011) A systematic review of studies on psychosocial late effects of childhood cancer: structures of society and methodological pitfalls may challenge the conclusions. Pediatr Blood Cancer 56:532–543. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.22883

Robison LL, Hudson MM (2014) Survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: life-long risks and responsibilities. Nat Rev Cancer 14:61–70. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3634

Muskat B, Jones H, Luchhetta S, Shama W, Zupanec S, Greenblatt A (2017) The experiences of parents of pediatric patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, 2 months after completion. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 34:358–366. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043454217703594

Stam HS, Grootenhuis MA, Brons PPT, Caron HN, Last BF (2006) Health-related quality of life in children and emotional reactions of parents following completion of cancer treatment. Pediatr Blood Cancer 47:312–319. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.20661

Wakefield CE, McLoone JK, Butow P, Lenthen K, Cohn RJ (2011) Parental adjustment to the completion of their child's cancer treatment. Pediatr Blood Cancer 56:524–531. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.22725

Wallander JL, Varni JW (1998) Effects of pediatric chronic physical disorders on child and family adjustment. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 39:29–46

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M et al (2015) Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 4:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

Pui CH, Evans WE (2013) A 50-year journey to cure childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Semin Hematol 50:185–196. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.seminhematol.2013.06.007

Cheung YT, Krull KR (2015) Neurocognitive outcomes in long-term survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated on contemporary treatment protocols: a systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 53:108–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.03.016

Kmet LM, Lee RC, Cook LS, Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (2004) Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research, Edmonton

de Vries MAG, van Litsenburg RRL, Huisman J, Grootenhuis MA, Versluys AB, Kaspers GJL, Gemke RJBJ (2008) Effect of dexamethasone on quality of life in children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a prospective observational study. Health Qual Life Out 6:103. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-6-103

Eiser C, Stride CB, Vora A, Goulden N, Mitchell C, Buck G, Adams M, Jenney MEM, the National Cancer Research Institute Childhood Leukaemia Sub-Group and UK Childhood Leukaemia Clinicians Network (2017) Prospective evaluation of quality of life in children treated in UKALL 2003 for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a cohort study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.26615

Fluchel M, Horsman JR, Furlong W, Castillo L, Alfonz Y, Barr RD (2008) Self and proxy-reported health status and health-related quality of life in survivors of childhood cancer in Uruguay. Pediatr Blood Cancer 50:838–843. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.21299

Furlong W, Rae C, Feeny D, Gelber RD, Laverdiere C, Michon B, Silverman L, Sallan S, Barr R (2012) Health-related quality of life among children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer 59:717–724. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.24096

Gordijn MS, van Litsenburg RR, Gemke RJ, Huisman J, Bierings MB, Hoogerbrugge PM, Kaspers GJL (2013) Sleep, fatigue, depression, and quality of life in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer 60:479–485. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.2426

Kobayashi K, Nakagami-Yamaguchi E, Hayakawa A, Adachi S, Hara J, Tokimasa S, Ohta H, Hashii Y, Rikiishi T, Sawada M, Kuriyama K, Kohdera U, Kamibeppu K, Kawasaki H, Oda M, Hori H (2017) Health-related quality of life in Japanese children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia during and after chemotherapy. Pediatr Int 59:145–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/ped.13092

Meeske K, Katz ER, Palmer SN, Burwinkle T, Varni JW (2004) Parent proxy–reported health-related quality of life and fatigue in pediatric patients diagnosed with brain tumors and acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer 101:2116–2125. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.20609

Mitchel HR, Lu X, Myers RM et al (2016) Prospective, longitudinal assessment of quality of life in children from diagnosis to 3 months off treatment for standard risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia: results of children’s oncology group study AALL0331. Int J Cancer 138:332–339. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.29708

Peeters J, Meitert J, Paulides M, Wiener A, Beck J, Calaminus G, Langer T (2009) Health-related quality of life (HRQL) in ALL-patients treated with chemotherapy only - a report from the late effects surveillance system in Germany. Klin Padiatr 221:156–161. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0029-1216366

Pogorzala M, Styczynski J, Kurylak A, Debski R, Wojtkiewicz M, Wysocki M (2009) Health-related quality of life among paediatric survivors of primary brain tumours and acute leukaemia. Qual Life Res 19:191–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-009-9580-1

Shankar S, Robison L, Jenney MEM et al (2005) Health-related quality of life in young survivors of childhood cancer using the Minneapolis-Manchester quality of life-youth form. Pediatrics 115:435–442. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-0649

van Litsenburg RRL, Huisman J, Raat H, Kaspers GJL, Gemke RBJ (2013) Health-related quality of life and utility scores in short-term survivors of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Qual Life Res 22:677–681. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-012-0183-x

Zheng DJ, Lu X, Schore RJ, Balsamo L, Devidas M, Winick NJ, Raetz EA, Loh ML, Carroll WL, Sung L, Hunger SP, Angiolillo AL, Kadan-Lottick NS (2018) Longitudinal analysis of quality-of-life outcomes in children during treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the children’s oncology group AALL0932 trial. Cancer 124:571–579. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.31085

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Poh Chua for assistance with the electronic literature search process and Bradley Drysdale for assisting in the review and data extraction process.

Funding

This project has been funded by The Monash Children’s Foundation, The Miranda Foundation, The Leukaemia Research Foundation, The Royal Children’s Hospital Foundation, and the Victorian Government Infrastructure Funding. Andrew Garas is supported by an Australian Government Postgraduate Award.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(PDF 119 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Garas, A., McLean, L.A., De Luca, C.R. et al. Health-related quality of life in paediatric patients up to five years post-treatment completion for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 27, 4341–4351 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04747-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04747-8