Abstract

Purpose

Rural cancer survivors may disproportionately experience financial problems due to their cancer because of greater travel costs, higher uninsured/underinsured rates, and other factors compared to their urban counterparts. Our objective was to examine rural-urban differences in reported financial problems due to cancer using a nationally representative survey.

Methods

We used data from three iterations of the National Cancer Institute’s Health Information and National Trends Survey (2012, 2014, and 2017) to identify participants who had a previous or current cancer diagnosis. Our outcome of interest was self-reported financial problems associated with cancer diagnosis and treatment. Rural-urban status was defined using 2003 Rural-Urban Continuum Codes. We calculated weighted percentages and Wald chi-square statistics to assess rural-urban differences in demographic and cancer characteristics. In multivariable logistic regression models, we examined the association between rural-urban status and other factors and financial problems, reporting the corresponding adjusted predicted probabilities.

Findings

Our sample included 1359 cancer survivors. Rural cancer survivors were more likely to be married, retired, and live in the Midwest or South. Over half (50.5%) of rural cancer survivors reported financial problems due to cancer compared to 38.8% of urban survivors (p = 0.02). This difference was attenuated in multivariable models, 49.3 and 38.7% in rural and urban survivors, respectively (p = 0.06).

Conclusions

A higher proportion of rural survivors reported financial problems associated with their cancer diagnosis and treatment compared to urban survivors. Future research should aim to elucidate these disparities and interventions should be tested to address the cancer-related financial problems experienced by rural survivors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The American Cancer Society estimates that there will be more than 20 million cancer survivors in the United States (U.S.) by 2020 [1]. The growing number of survivors is a testament to the success of early detection and treatment efforts [1]. However, the direct (e.g., costs due to hospitalizations, cancer treatments, physician visits) and indirect costs (e.g., time away from work, lost productivity) of cancer diagnosis and treatment can negatively impact survivors [2]. Previous studies suggest that nearly one in three survivors experience cancer-related financial problems (e.g., debt, bankruptcy, out-of-pocket medical costs) that may lead to delaying or forgoing medical care [3, 4]. Financial barriers experienced during and following cancer treatment may be compounded by factors such as institutional racism, socioeconomic status, inadequate insurance coverage, and geographic residence [3,4,5,6,7].

Survivors from rural areas may experience greater cancer-related financial problems compared to their urban counterparts. Rural cancer patients often have higher treatment-related travel costs, higher rates of no insurance or under-insurance, and less flexible work leave policies that may exacerbate the financial problems associated with cancer [8]. Due to the financial burden of cancer diagnosis and treatment, rural patients are more likely to forgo medical care following cancer treatment (e.g., continued surveillance, screening for other cancers, and taking prescribed medication) compared to their urban counterparts [7, 9].

However, there is inadequate research examining rural-urban differences in financial problems among cancer survivors in the US. Previous rural-urban studies have either been confined to a single cancer in a single state, performed in Canada, or only studied those under the age of 65 or in active treatment [10,11,12]. Therefore, our objective was to evaluate rural-urban differences in reported financial problems among cancer survivors by utilizing three cycles of a nationally representative survey, the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS).

Methods

Study design and sample

HINTS is a nationally representative, cross-sectional survey conducted by the NCI that collects data on health information-seeking, risk perceptions, cancer-relevant health behaviors (e.g., smoking, diet, screening), and other areas germane to cancer communication. Westat provides a detailed description of the HINTS survey sampling and dissemination process, which we summarize here [12]. Survey participants included non-institutionalized adults aged 18 years and older who were sampled using a two-stage sampling approach. In this approach, addresses were randomly sampled (stage 1), and the adult with the next birthday at a selected address was asked to participate as determined by one of the survey questions (stage 2). Non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics were oversampled to ensure more precise racial/ethnic minority estimates. The HINTS survey protocol utilized a modified Dillman approach included four mailings: an initial mailing that included a cover letter, questionnaire, return envelope and a $2 bill, a reminder postcard (1 week following initial mailing), and two follow-up mailings (1 and 2 months following initial mailing, respectively).

We used the HINTS 4 Cycle 2 (2012), HINTS 4 Cycle 4 (2014), and HINTS 5 Cycle 1 (2017) datasets, which specifically asked about financial burden among respondents with a history of cancer [13]. The overall response rates for these cycles were 40.0%, 34.4%, and 32.4%, respectively, similar to that of other nationally representative surveys [14]. Each HINTS survey cycle included a unique sample of participants, i.e., individuals are not tracked longitudinally over time.

Outcome variable

Participants in these three HINTS cycles indicating a previous or current cancer diagnosis were asked: “Looking back, since the time you were first diagnosed with cancer, how much, if at all, has cancer and its treatment hurt your financial situation?” Answer options included not at all, a little, some, and a lot. The response categories were collapsed to “not at all” vs. “a little, some, a lot.” This follows the precedent of similar studies that dichotomized survey responses by any level of financial problems vs. no financial problems [3, 4].

Sample characteristics

Survivor-level characteristics included gender, age, marital status, race/ethnicity, income, census region, occupational status, current insurance status, and number of comorbidities. Participants were asked about whether they had ever been diagnosed with the following condition: hypertension, heart disease, lung disease, diabetes, arthritis, and depression. Additionally, participants were asked their height and weight, from which their body mass index was determined (i.e., presence of obesity). We summed the presence of each of the self-reported conditions and obesity to categorize comorbidities as 0, 1–2, or 3+. Cancer experience characteristics included receipt of surgery, receipt of chemotherapy, receipt of radiation, and time since last treatment. All of these cancer experiences characteristics have been considered in previous studies assessing financial problems associated with cancer [3, 4].

Rural-urban status

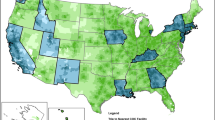

Rural-urban status was determined using the 2003 US Department of Agriculture Rural-Urban Continuum Codes (RUCC), which categorize counties along a continuum based upon their population size and adjacency to a metropolitan area [15]. As done in previous HINTS analyses, RUCCs with values 1–3, indicative of metro counties, were used to denote participants from urban counties, while RUCCs with values 4–9 were used to indicate participants from rural, or non-metro, counties [16].

Statistical methods

We combined data from the three HINTS cycles into a single dataset containing sample and replicate weights in accordance with NCI recommendations for analyses of multiple survey cycles [17]. For variables with a notable level of missing data like race/ethnicity (> 10% missing) and gender (> 5% missing), we employed multiple imputation by fully conditional specification, which is an appropriate approach for the complex survey design of HINTS [18]. This approach is advantageous because it produces less biased estimates with more precise effects than a complete case analysis when large amounts (> 10%) of missing data are present [19]. Using this procedure, we created ten multiple imputation datasets from which test statistics were derived.

We present rural-urban differences in demographic and cancer experience characteristics as weighted percentages and compared them using Wald’s chi-square statistics. We also performed multivariable logistic regression and reported adjusted predicted probabilities [20]. We included the following survivor-level demographic and cancer experience characteristics as covariates in the multivariable model: gender, age, marital status, race, ethnicity, income, census region, occupational status, insurance status, comorbidities, receipt of surgery, receipt of chemotherapy, receipt of radiation, and time since last treatment. These covariates were chosen because they have been examined in previous studies exploring the relationship between cancer survivorship and financial problems [3, 4]. Reporting adjusted predicted probabilities has frequently been used in the analysis of complex survey data. It directly standardizes group outcomes to the covariate distribution of the overall population and can be compared as percentages. We also present the adjusted odds ratios from this model as well as unadjusted odds ratios in Supplementary Table 1.

Approximately one-fifth of our study sample indicated a non-melanoma skin cancer diagnosis, a group that is frequently excluded from studies of financial problems among cancer patients due to their less intensive treatment regimen [3, 4]. To maximize our sample size, we retained these individuals in our main analysis. However, we did perform a sensitivity analysis to see if results differed when non-melanoma skin cancer cases were excluded.

Multiple imputation and all analyses were performed in SAS 9.4 using appropriate procedures to account for the complex survey design [21]. Statistical significance tests were two-sided and set at p < 0.05. The study was deemed exempt by the University of South Carolina Institutional Review Board.

Results

Sample characteristics

Across the three HINTS cycles, 1368 participants reported a previous or current cancer diagnosis (12.9%), 99.3% (n = 1359) of whom provided valid responses to the survey question on financial problems related to cancer diagnosis and treatment. This included 454 participants from the 2012 HINTS survey, 459 from 2014, and 446 from 2017. Rural and urban cancers survivors statistically significantly varied by census region, marital status, and occupational status, but did not differ by other characteristics (Table 1). Three-fourths of rural cancer survivors lived in the Midwest or South, and 73.9% of rural cancer survivors were married/living as married (vs. 65.4% of urban cancer survivors). More than half (51.4%) of rural cancer survivors were retired.

Rural-urban differences in cancer-related financial problems

In unadjusted analyses, for all survey cycles combined, 50.4% of rural cancer survivors indicated financial problems following their diagnosis and treatment compared to 38.8% of urban survivors (difference = 11.6%, p = 0.02) (Fig. 1a). There were no statistically significant rural-urban differences in reported financial problems across survey cycle. Figure 1b displays unadjusted rural-urban differences in financial problems by income level with the lowest income reporting the highest burden in both groups. Non-white rural cancer survivors had the highest unadjusted reported financial problems (71.2%) of all race/rural categories (Fig. 1c).

After adjustment for covariates, 49.3% of rural cancer survivors reported financial problems following diagnosis and treatment compared to 38.7% of urban survivors, but this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.06) (Table 2). A higher proportion of survivors who received chemotherapy reported financial problems compared to those who did not receive chemotherapy (64.6 and 34.0%, respectively, p < 0.001). Financial problems were also more likely to be reported among those who received radiation compared to those who did not (54.8 and 35.1%, respectively, p = 0.007). Reporting of financial problems also varied by time since last treatment; those who were currently undergoing treatment or who had received their last treatment within the past year indicated the highest proportion of financial problems (51.7%) after adjustment for covariates (p = 0.04). Reported financial problems increased with decreasing income levels; 29.7% of cancer survivors making $75,000+ reported financial problems compared to 55.2% at the lowest income level ($0–$19,999) (p = 0.04). There were no statistically significant differences in reported financial problems for any other survivor-level characteristics.

Sensitivity analysis, which excluded survivors with a non-melanoma skin cancer diagnosis, showed a somewhat similar adjusted non-statistically significant difference between rural and urban survivors (54.2 and 45.1%, respectively, p = 0.21), (Supplementary Table 2).

Discussion

We used multiple iterations of a nationally representative, population-based survey to assess rural-urban differences in reported financial problems associated with cancer diagnosis and treatment. In unadjusted analysis, a significantly higher proportion of rural survivors (more than half) reported having financial problems due to cancer compared to their urban counterparts. Further, a large proportion of minority and low-income rural cancer survivors reported financial problems. Accounting for covariates, the difference between rural and urban survivors reporting cancer-related financial problems was no longer statistically significant.

We found that approximately half of rural cancer survivors reported financial problems related to their cancer compared to just over a third of urban cancer survivors, though these differences were explained by demographic and treatment characteristics. Our findings corroborate a recent study in New Mexico found that rural colorectal cancer patients were nearly twice as likely as their urban counterparts to report financial hardship related to their treatment. A study of 2011 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey data that found cancer survivors in active treatment in non-metropolitan areas were more likely to report financial hardship associated with their cancer [9, 11]. Our study, which used data collected in 2012, 2014, and 2017, found an overall prevalence of cancer-related financial burden among rural cancer survivors that was 20 percentage points higher than previous nationally representative studies in which data were collected in 2010 and 2011 [3, 4, 11]. This may suggest that cancer-related financial problems have increased in recent years; particularly affecting rural survivors. Similarly, we found that non-white rural cancer survivors had financial problems due to their cancer diagnosis. Previous research has shown that African Americans experience greater financial problems due to cancer diagnosis, and our findings in particular suggest that the interplay between place and race is important as well [6, 22]. Although our study was underpowered to detect temporal trends within our study period, future studies should further explore rural-urban differences in financial problems over time and by racial and ethnic differences.

The high levels of financial burden particularly among rural cancer survivors underscore the importance of improving provider-level and system-level processes to address cancer-related financial burden—both due to direct medical expenditures as well as out-of-pocket non-medical and indirect costs (e.g., transportation, lost wages). Evidence of disconnect in patient-provider communication around cancer-related financial problems has been reported [23]. A study of breast cancer patients found that 73% of those who were concerned about finances did not receive desired financial or employment guidance from their cancer care providers, even though 51% of providers believed that they always discussed the financial burden of cancer with their patients [23]. Improved patient-provider communication or the addition of ancillary staff (e.g., financial navigators) to support financial counseling may help address these challenges [5, 25,26,27,28]. One study found that half of patients who discussed costs with their oncologists reported lower out-of-pocket costs for treatment as a result (e.g., referrals to financial assistance programs, changes to less expensive medications) [28]. At the system level, it is critical for clinicians to provide or refer their patients for financial counseling and navigation, especially considering that rural patients may face unique transportation barriers and related opportunity costs (e.g., additional costs due to the need to find accommodations ahead of treatment and subsequent additional lost income during treatment) [10, 29]. Studies have shown that patient navigation programs may help rural cancer patients navigate the health insurance landscape, address both out-of-pocket and non-medical costs that mount during treatment, and other financial challenges (e.g., taking unpaid leave from work) that may occur during cancer treatment [30, 31]. Unfortunately, these ancillary supports may be more likely to be needed more in rural areas, and simultaneously less likely to be available. However, some cancer screening programs have found success through formal linkages between community and clinical partners and utilizing clinical protocols to facilitate such programs [32]. Future interventions with financial and/or patient navigators should seek to address and/or optimize these unmet resource needs in rural areas.

Our multivariable analysis indicated that treatment factors (i.e., receipt of chemotherapy and/or radiation and more recent completion of treatment) were associated with higher reported financial burden related to a cancer diagnosis. Findings related to treatment factors corroborated several previous studies [3, 4, 33]. The cost of cancer care was projected to increase 27% between 2010 and 2020, which overlaps with the survey periods, but these cost projections vary by cancer type [34]. Future studies with larger samples should explore the role that cancer type plays in subsequent patient-reported financial problems. Additionally, HINTS only queried cancer survivors on the receipt of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation. With the increasing use of expensive targeted drug therapies and immunotherapies, future research should also examine the effect that these treatments may have on the finances of cancer survivors and their families [35, 36]. This may be particularly important among rural populations who are more likely to be uninsured and underinsured and are more likely to forgo treatment due to cost [8,9,10].

We found no statistically significant association between age and financial hardship associated with cancer, which was unexpected and is in contrast to previous studies that found younger cancer survivors were more likely to experience financial hardship associated with their cancer [3, 4, 33]. This may be due in part to the dichotomous nature of the insurance status question in HINTS, which prevented us from examining the interplay between age and specific types of insurance and their effects on cancer-related financial problems. Such prior studies suggest that patients under the age of 65 with private insurance compared to those with public insurance or no insurance [11]; additional research in this area and variation due to individual and geographic characteristics are warranted. We were also unable to account for employment changes that occurred as a result of a cancer diagnosis like studies that used the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) Experiences with Cancer questionnaire [4], and employment changes could contribute to age related differences in reported financial problems with cancer care. However, unlike previous studies, we included rural-urban status in our adjusted model. This may help explain any age differences in reported financial problems associated with cancer diagnosis and treatment. An analysis of 2006–2010 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data showed that both rural cancer survivors aged 18–64 and those 65 and older were more likely to forgo medical care due to costs in unadjusted analysis [7]. This finding remained in those over the age of 65 after adjusting for race/ethnicity, age as a continuous variable, marital status, insurance status, comorbidities, health status, time since diagnosis, and geographic region, but was attenuated among younger survivors. This suggests that the relationship between age and rural-urban status and their effect on cancer-related financial problems is complex and warrants additional study. Future iterations of HINTS would also benefit from additional questions on rural-urban status and insurance status at time of diagnosis, not solely at time of survey completion, as well as more specific questions on the financial hardship of cancer.

Limitations and strengths

Our study was not without limitations. First, despite using all survey cycles in which financial burden was assessed, we had a small rural sample (n = 233), which may have made our study insufficiently powered to detect differences, a common challenge in studies of small populations [37]. Due to small sample sizes and poor representation of the more rural RUCCs, we chose to collapse the RUCCs into one rural category. Use of a more granular characterization of rural may have more effectively identified the effect of the rural-urban gradient on cancer-related financial burden. This small sample size also prevented us from examining the effect of cancer type. Additionally, HINTS included a single survey question related to financial problems (i.e., how one’s finances were “hurt”), restricting our ability to further explicate the specific problems experienced (e.g., bankruptcy, debt, loss of employment) and the duration of those problems on the patient and their families. Survey participants may have interpreted the word “hurt” differently, and thus, the tangible implication of survey responses may differ among cancer survivors, which warrants additional study using qualitative or mixed methods.

Despite these limitations, our study begins to address critical gaps in our knowledge of rural and urban disparities in cancer care. A strength of our study is that we used a nationally representative, population-based survey including multiple years of data to examine rural-urban differences in financial problems associated with cancer. Using the 2012, 2015, and 2017 HINTS data also provides a more recent assessment of financial problems compared to other analyses of national surveys such as the 2010 NHIS and the 2011 MEPS Experiences with Cancer questionnaire [3, 4]. Additionally, our study is one of the first to assess, at a national level, the predicted probability of cancer-related financial problems by rural-urban status. Future research should more adequately sample rural populations and include both more comprehensive questions and more specific response options to evaluate cancer-related financial problems.

Conclusions

Our study found that a higher proportion of rural cancer survivors reported financial problems associated with their diagnosis and treatment compared to urban survivors, although this difference was attenuated after adjusting for demographic and treatment characteristics. It is especially important to address the financial problems associated with cancer among rural populations through interventions to improve provider-patient communication, increase access to financial navigation programs, and to adapt and implement contextually tailored interventions. Additionally, future research that oversamples rural populations may more effectively elucidate the effect of rural-urban residence on cancer-related financial burden and highlight the contextual nuances found in rural communities.

References

Miller KD, Siegel RL, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, Kramer JL, Rowland JH (2016) Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin 66(4):271–289. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21349

Yabroff KR, Lund J, Kepka D, Mariotto A (2011) Economic burden of cancer in the US: estimates, projections, and future research. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 20(10):2006–2014. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0650

Kent EE, Forsythe LP, Yabroff KR, Weaver KE, de Moor JS, Rodriguez JL (2013) Are survivors who report cancer-related financial problems more likely to forgo or delay medical care? Cancer 119(20):3710–3717. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28262

Yabroff KR, Dowling EC, Guy GP Jr, Banegas MP, Davidoff A, Han X et al (2016) Financial hardship associated with cancer in the United States: findings from a population-based sample of adult cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 34(3):259–267. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2015.62.0468

Yabroff KR, Zhao J, Zheng Z, Rai A, Han X (2018) Medical financial hardship among cancer survivors in the United States: what do we know? What do we need to know? Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 27:1389–1397

Wheeler SB, Spencer JC, Pinheiro LC, Carey LA, Olshan AF, Reeder-Haynes KE (2018) Financial impact of breast cancer in black versus white women. J Clin Oncol (36(17)):1695–1701. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.77.6310

Palmer NR, Geiger AM, Lu L, Case LD, Weaver KE (2013) Impact of rural residence on forgoing healthcare after cancer because of cost. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 22(10):1668–1676. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.epi-13-0421

Charlton M, Schlichting J, Chioreso C, Ward M, Vikas P (2015) Challenges of rural cancer care in the United States. Oncology (Williston Park) 29(9):633–640

McDougall JA, Banegas MP, Wiggins CL, Chiu VK, Rajput A, Kinney AY (2018) Rural disparities in treatment-related financial hardship and adherence to surveillance colonoscopy in diverse colorectal cancer survivors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 27(11):1275–1282. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.epi-17-1083

Mathews M, West R, Buehler S (2009) How important are out-of-pocket costs to rural patients’ cancer care decisions? Can J Rural Med 14(2):54–60

Whitney RL, Bell JF, Reed SC, Lash R, Bold RJ, Kim KK et al (2016) Predictors of financial difficulties and work modifications among cancer survivors in the United States. J Cancer Surviv 10(2):241–250

WeStat (2017) Health Information National Trends Survey 5 (HINTS 5) Cycle 1 Methodology Report July 2017. https://hints.cancer.gov/docs/methodologyreports/HINTS5_Cycle_1_Methodology_Rpt.pdf Accessed 1 October 2018

National Cancer Institute (2018) HINTS Public Use Dataset. Available at https://hints.cancer.gov/data/download-data.aspx Accessed on 1 August 2018

Czajka JL and Beyler A. Declining response rates in federal surveys: trends and implications. https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/255531/Decliningresponserates.pdf. Accessed 23 Sept 2018

United States Department of Agriculture (2016). Rural Urban Continuum Codes. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes. Accessed 1 Aug 2018

Greenberg AJ, Haney D, Blake KD, Moser RP, Hesse BW (2018) Differences in access to and use of electronic personal health information between rural and urban residents in the United States. J Rural Health 34 Suppl 1:s30-s8 doi 10.1111/jrh.12228:s30–s38

National Cancer Institute (2017) Analytics recommendations for HINTS 5, Cycle 1 Data November, 2017. https://hints.cancer.gov/data/download-data.aspx Accessed 1 October 2018

van Buuren S (2007) Multiple imputation of discrete and continuous data by fully conditional specification. Stat Methods Med Res 16(3):219–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/0962280206074463

Lee KJ, Carlin JB (2012) Recovery of information from multiple imputation: a simulation study. Emerg Themes Epidemiol 13(9(1)):3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-7622-9-3

Graubard BI, Korn EL (1999) Predictive margins with survey data. Biometrics 55(2):652–659

SAS Institute Inc. (2009) SAS/STAT ® 9.2 User’s Guide SEC. SAS Institute Inc, NC, p 2018

Probst JC, Moore CG, Glover SH, Samuels ME (2004) Person and place: the compounding effects of race/ethnicity and rurality on health. Am J Public Health 94(10):1695–1703

Jagsi R, Ward KC, Abrahamse PH, Wallner LP, Kurian AW, Hamilton AS et al (2018) Unmet need for clinician engagement regarding financial toxicity after diagnosis of breast cancer. Cancer 124(18):3668–3676. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.31532

Shih YT, Chien CR (2017) A review of cost communication in oncology: patient attitude, provider acceptance, and outcome assessment. Cancer 123(6):928–939. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30423

Meropol NJ, Schrag D, Smith TJ, Mulvey TM, Langdon RM Jr, Blum D et al (2009) American Society of Clinical Oncology guidance statement: the cost of cancer care. J Clin Oncol 27(23):3868–3874. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.23.1183

Shankaran V, Leahy T, Steelquist J, Watabayashi K, Linden H, Ramsey S et al (2018) Pilot feasibility study of an oncology financial navigation program. J Oncol Pract 14:e122–e129

Zullig LL, Wolf S, Vlastelica L, Shankaran V, Zafar SY (2017) The role of patient financial assistance programs in reducing costs for cancer patients. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 23:407–411

Zafar SY, Chino F, Ubel PA, Rushing C, Samsa G, Altomare I et al (2015) The utility of cost discussions between patients with cancer and oncologists. Am J Manag Care 21(9):607–615

Butow PN, Phillips F, Schweder J, White K, Underhill C, Goldstein D (2012) Psychosocial well-being and supportive care needs of cancer patients living in urban and rural/regional areas: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 20(1):1–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-011-1270-1

Vanderpool RC, Nichols H, Hoffler EF, Swanberg JE (2017) Cancer and employment issues: perspectives from cancer patient navigators. J Cancer Educ 32(3):460–466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-015-0956-3

Palomino H, Peacher D, Ko E, Woodruff SI, Watson M (2017) Barriers and challenges of cancer patients and their experience with patient navigators in the rural US/Mexico border region. J Cancer Educ 32(1):112–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-015-0906-0

Inrig SJ, Higashi RT, Tiro JA, Argenbright KE, Lee SJ (2017) Assessing local capacity to expand rural breast cancer screening and patient navigation: an iterative mixed-method tool. Eval Program Plann 61:113–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2016.11.006

Gordon LG, Merollini KMD, Lowe A, Chan RJ (2017) A systematic review of financial toxicity among cancer survivors: we can’t pay the co-pay. Patient 10(3):295–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-016-0204-x

Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, Feuer EJ, Brown ML (2011) Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010-2020. J Natl Cancer Inst 103(2):117–128. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djq495

Shih YT, Smielauskas F, Geynisman DM, Kelly RJ, Smith TJ (2015) Trends in the cost and use of targeted cancer therapies for the privately insured nonelderly: 2001 to 2011. J Clin Oncol 33(19):2190–2196

Tran G, Zafar SY (2018) Financial toxicity and implications for cancer care in the era of molecular and immune therapies. Ann Transl Med 6(9):166

Srinivasan S, Moser RP, Willis G, Riley W, Alexander M, Berrigan D et al (2015) Small is essential: importance of subpopulation research in cancer control. Am J Public Health 105(Suppl 3):S371–S373. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2014.302267

Data

This study used secondary data from the National Cancer Institute. The “Data Terms of Use” does not allow for release of data by data users. However, these data are publicly available from the National Cancer Institute and available for download on their website upon acknowledgement of the “Data Terms of Use.”

Funding

This publication was supported, in part, by the Cancer Prevention and Control Research Network, funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Cancer Institute (3 U48 DP005000-01S2, University of South Carolina PI: Friedman, Authors: Zahnd, Odahowski, and Eberth; 3 U48 DP005006-01S3, Oregon Health & Science University PI: Shannon and Winters-Stone, Authors: Davis, Perry, Farris, Shannon; 3 U48 DP005014-01S2, University of Kentucky PI: Vanderpool, Author: Vanderpool; 3 U48 DP005013-01S1A3, University of Washington PI: Hannon, Author: Ko; and 3 U48 DP005017-01S8, University of North Carolina PI: Wheeler, Authors: Wheeler and Rotter). Melinda Davis was supported in part by an NCI K07 award (1K07CA211971-01A1). Linda Ko was supported in part by a grant from the Clinical and Translational Science Awards program (UL1 TR002319). This study was also supported by the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy (FORHP), Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under cooperative agreement [5 U1CRH30539-03-00; Eberth, Zahnd, Odahowski].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer

The information, conclusions, and opinions expressed in this brief are those of the authors and no endorsement by FORHP, HRSA, CDC, NIH, or HHS is intended or should be inferred.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 19 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zahnd, W.E., Davis, M.M., Rotter, J.S. et al. Rural-urban differences in financial burden among cancer survivors: an analysis of a nationally representative survey. Support Care Cancer 27, 4779–4786 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04742-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04742-z