Abstract

Purpose

The semantics of defining cancer cachexia over the last decade has resulted in uncertainty as to the prevalence. This has further hindered the recognition and subsequent treatment of this condition. Following the consensus definition for cancer cachexia in 2011, there is now a need to establish estimates of prevalence. Therefore, the primary aim of the present study was to assess the prevalence of cachexia in an unselected cancer population. A secondary aim was to assess patient-perceived need of attention to cachexia.

Methods

A cross-sectional study in hospital patients was undertaken. Key inclusion criteria were the following: age > 18 years, cancer diagnosis, and no surgery the preceding 24 h. Data on demographics, disease, performance status, symptoms, cachexia, and patients’ perceived need of attention to weight loss and nutrition were registered.

Results

Data were available on 386 of 426 eligible patients. Median age (IQR) was 65 years (56–72), 214 (55%) were male and 302 (78%) had a performance status of 0–1 (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group). Prevalence of cachexia (inpatients/outpatients) was 51/22%. Prevalence was highest in patients with gastrointestinal cancer (62/42%) and lung cancer (83/36%). There was no major difference in prevalence between patients with metastatic (55/24%) and localized disease (47/19%). Twenty percent of inpatients and 15% of outpatients wanted more attention to weight loss and nutrition. Cachexia (p < 0.001), symptoms of mood disorder (p < 0.001), and male gender (p < 0.01) were independently associated with increased need of attention.

Conclusion

Cachexia is a prevalent condition, affecting both patients with localized and metastatic cancer. Clinical attention to the condition is a sizeable unmet need.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cancer cachexia is characterized by loss of muscle mass (with or without loss of fat mass) and anorexia, and is caused by a combination of abnormal metabolism and reduced nutritional intake [1]. It leads to impaired physical function, reduced tolerability of anti-cancer treatment, and psychosocial distress [2,3,4]. Cachexia remains one of the greatest challenges in cancer as it causes up to 20% of cancer-related deaths [5] but has no established treatment.

The reported prevalence of cancer cachexia has varied substantially [6,7,8], with one of the main reasons being the heterogeneity of cachexia definitions [9]. In 2011, a consensus definition stated that cachexia is present when either (a) weight loss exceeds 5% last 6 months or (b) weight loss exceeds 2% in conjunction with either body mass index (BMI) < 20 kg/m2 or sarcopenia [1]. Using this definition, two studies have examined cachexia prevalence. Wallengren et al. [10] reported a prevalence of 85% in patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative care. The vast majority of these patients had gastrointestinal cancer, which is known to be associated with a relatively high prevalence of cachexia. Sun et al. [11] reported in contrast a prevalence of 36% in a Chinese population with advanced cancer of several types. Uncertainty concerning prevalence of cachexia, demonstrated by these two studies and previous work [6,7,8], indicates that the prevalence of cachexia remains unclear. Furthermore, while it is known that prevalence varies with cancer type [12], it is uncertain as to whether the prevalence changes with other disease-related or demographic factors. For example, do patients with metastatic cancer have a higher prevalence of cachexia? While the latter would seem unsurprising, this is still not known and there is a need to estimate the prevalence of cancer cachexia at different stages as well as within other clinical and demographic strata.

Knowledge of prevalence of conditions is important in the planning for provision of health care services. In cachexia, a precise estimate of prevalence is important when assessing the need for palliative care, including nutritional interventions, physiotherapy, psychosocial care, and other relevant supportive treatments. In addition, emerging pharmaceutical treatments against cachexia [13] warrant more information regarding prevalence, considering their potential impact on health economy.

An understanding of prevalence might also have an impact at an individual level by motivating health care professionals to focus more on cachexia. This is desirable since qualitative research has shown that patients with cancer commonly experience concerns about weight loss and eating-related problems [14]. Lack of attention to these issues contributes to increased concern for both patients and their relatives [15]. However, it is reported that some health care professionals avoid talking to patients and families about cachexia due to fear of increasing patients’ distress by asking questions about untreatable conditions [16]. Thus, an assessment of the patient-perceived need for clinical attention to weight loss and nutrition seem warranted, and knowledge about the characteristics of patients with such needs would facilitate their identification.

In summary, uncertainty about the prevalence of cancer cachexia is a barrier against proper management and awareness of the syndrome, and the identification of patients with an unmet need for attention to cachexia could enable interventions aimed at relieving psychosocial distress. To this end, the primary aim of this study was to provide an estimate for the overall prevalence of cachexia in an unselected population of patients with cancer, and to estimate prevalence in different strata based on demographic and clinical factors (gender, cancer type, cancer stage, etc.). Secondary aims were to assess patient-perceived need of clinical attention to issues concerning weight loss and nutrition and to explore which factors are associated with such a need.

Methods

Study design and patients

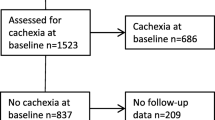

A cross-sectional study was conducted among in- and outpatients at three sites: a university hospital, a local hospital, and a community hospital, all within the Central Norway Regional Health Authority, serving a total population of 700,000. The overall aim was to quantify severity and prevalence of pain, cachexia, and mood disorder. Data pertaining to cancer cachexia were extracted for the purpose of the present paper. All inpatients with cancer at departments of surgery, internal medicine, and medical and radiation oncology were screened and approached on predefined days in September 2013. The outpatients were recruited from the department of medical and radiation oncology at the university hospital in January 2014. As different primary tumor types cluster on specific days of the week, the recruitment of outpatients was spread out over 10 predefined days (such that each day of the week was represented twice) to avoid selection bias. Eligible patients had cancer, were aged > 18 years, were able to read and write Norwegian, and had sufficient cognitive function to complete assessments. To minimize possible influence of temporary post-operative symptoms (nausea, pain, etc.), patients who had had surgery in the preceding 24 h were excluded. All patients provided written, informed consent, and the study was approved by the regional committee for medical and health research ethics.

Management of cancer in Norway in relation to study design

Norwegian cancer care is rarely privatized, and most cancers are treated regionally. The majority of patients are treated on an outpatient basis, while hospital beds are reserved for patients needing emergency care, extensive surgery, or intensive chemotherapy. At the time of the study, nutritional status was not assessed routinely, and referral to a dietician was based on individual physician’s discretion.

Data collection

Cancer type, cancer stage (local/locally advanced versus metastatic), oncologic treatment, treatment intent (curative versus palliative), and performance status (Karnofsky [17] or Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group [ECOG] [18]) were recorded by health care personnel. To achieve a homogenous classification of performance status (PS), Karnofsky PS and ECOG PS were converted into three groups corresponding to ECOG PS 0–1, ECOG PS 2 or ECOG PS 3–4 [19]. Patients were asked to complete a study-specific form including questions about demographic data and several patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). As in a study [20] validating the international consensus definition of cachexia [1], weight 6 months before inclusion, current height and weight, and food intake in the preceding 2 weeks (reduced, unchanged, or increased) were reported by the patient using the Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA) [21]. The PG SGA was also used to assess nutritional impact symptoms, which are predefined symptoms that the patients were asked to report if they were present and had had impact on their dietary intake. Item 1 from the Brief Pain Inventory (Short Form) [22] was used to assess if the patient was bothered by pain or not. The 7-item Chalder Physical Fatigue Scale (maximum range 0–21) [23] was used to assess fatigue and the 4-item Patient Health Questionnaire for Depression and Anxiety (maximum range 0–12) [24] was used to assess symptoms of mood disorder. Patients were also asked to score on a study-specific Likert-type scale whether they wanted their physician to focus less or more on weight loss and nutrition. The answer options were “A lot less focus,” “Less focus,” “Sufficient as it is,” “More focus,” and “A lot more focus.”

Statistical considerations

As the primary aim of this study was a descriptive analysis of symptom prevalence and severity, no power calculations were performed. However, it was estimated that 60 inpatients and 160 outpatients would be sufficient to achieve the primary aim. Cachexia was deemed to be present if the patient had either (a) weight loss > 5% (6 months) or (b) weight loss > 2% (6 months) and BMI < 20 kg/m2. This minor adaptation of the international consensus definition [1] has been validated previously [20]. The difference is that sarcopenia is not included as a criterion. Prevalence of cachexia was estimated in total and by age, gender, cancer stage, cancer type, oncologic treatment, and treatment intent. Due to differences in length of recruiting and the resulting disproportionate sample sizes in in- and outpatients, as well as the clinical differences between inpatients and outpatients demonstrated in an earlier publication from this dataset [25], prevalence results were reported separately for the two groups. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression models were estimated to determine associations between cachexia and the factors listed above.

Patient-perceived need of clinical attention to weight loss and nutrition was estimated and stratified by in-/outpatients and cachexia/no cachexia. The Likert-type answer options were assigned values from 1 to 5, and univariable and multivariable linear regression models were estimated to determine associations between the need of clinical attention to weight loss and nutrition and demographical factors, disease and treatment specific factors, cachexia, food intake, pain, fatigue, and symptoms of mood disorder.

In the logistic regression (concerning cachexia prevalence), all factors from univariable regression analysis were entered initially into the multivariable model, while in the linear regression (concerning need of clinical attention to weight loss and nutrition) only factors with p value < 0.25 were entered initially due to the large number of variables. In both regression analyses, factors were later removed if not significantly contributing to the model according to likelihood ratio test. All remaining factors were then tested for significant interactions. To increase power of the regression analyses, in- and outpatients were analyzed together in both univariable and multivariable analyses. Consequently, the variable in-/outpatient were added to the multivariable models to adjust for a potential effect due to the setting. A two-sided p value < 0.05 was considered significant.

To test the robustness of the multivariable linear regression, a sensitivity analysis was performed using both logistic and ordered logistic regression. In the logistic regression, the outcome variable was dichotomized as “Sufficient as it is” or below vs “More focus” or above. In the ordered logistic regression, a model of proportional odds was used to estimate the probability of patients answering one of the five ordinal categories ranging from “A lot less focus” to “A lot more focus”. Stata version 13.1 for Windows (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA) was used for statistical analyses.

Results

In total, 426 patients with cancer were recruited. Of these, 40 patients were excluded due to missing data on weight loss or BMI, leaving 386 patients included in the final analysis. Median age was 65 years (IQR 56–72), 214 patients (55%) were male, most had an ECOG PS of 0–1 (302, 78%), and were outpatients (308, 80%) (Table 1). The 40 patients who were excluded had a median age of 69 years (IQR 63–75), 38% were male, 65% had an ECOG PS of 0–1, and 85% were outpatients. Only the gender distribution was significantly different between the included and excluded patients.

Cachexia prevalence

Current weight and BMI were similar for in- and outpatients, but inpatients reported greater 6 months weight loss (6.3 versus 1.7 kg), and 62% of inpatients versus 24% of outpatients reported that dietary intake had been less than usual the preceding 2 weeks (Table 2). Appetite loss, early satiety, and altered taste were the most prevalent nutritional impact symptoms in inpatients, while altered taste, early satiety, and dry mouth were the most prevalent symptoms in outpatients. Nutritional impact symptoms were more prevalent in inpatients, than in outpatients (Table 2). Prevalence of cachexia was 51% (95%CI 40–63%) among inpatients and 22% (95%CI 17–27%) among outpatients. Prevalence varied depending on cancer type. It was highest in patients with gastrointestinal cancer (inpatients 62%/outpatients 42%) and lung cancer (83/36%), and lowest in patients with breast cancer (−/11%) and hematologic cancer (13/19%) (Table 3).

Prevalence was consistently higher in patients with incurable cancer (61/26%) compared to curable cancer (43/17%). Cachexia prevalence varied less with regard to cancer stage as it was only a little higher in patients with metastatic disease (52/25%) compared to patients with local or locally advanced disease (44/19%) (Table 3).

Multivariable logistic regression, adjusted by setting, confirmed that cachexia prevalence was strongly associated with cancer type. Lung cancer (OR 5.5, p < 0.01) and gastrointestinal cancers (OR 4.4, p < 0.001) were significantly more associated with cachexia compared to hematologic cancers. Treatment type, treatment intent, cancer stage, age, and gender did not significantly contribute to the multivariable model and were left out of the final model.

Clinical attention to weight loss and nutrition

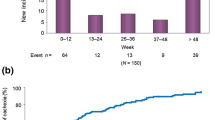

When inpatients were asked whether they wanted their physician to focus less or more on weight and nutrition, 3% answered that they wanted “less focus” or “a lot less focus,” 78% that the attention was “sufficient as it is,” and 20% that they wanted “more focus” or “a lot more focus.” Among outpatients, the respective proportions were 5, 80, and 15%. When stratifying on cachexia, 37% of inpatients and 33% of outpatients with cachexia wanted “more focus” or “a lot more focus,” while only 3% of inpatients and 10% of outpatients without cachexia expressed the same need (Fig. 1). Two inpatients and 46 outpatients did not answer the question.

Univariable analyses in respondents identified that the following factors were significantly associated with a request for more attention to weight loss and nutrition: male gender, 10–12 years of education, cachexia, reduced food intake, lung cancer, symptoms of mood disorder, and palliative treatment intention (Table 4). In the multivariable analyses, adjusted by setting, it was shown that cachexia (p = 0.02), symptoms of mood disorder (p = 0.05), and male gender (p < 0.01)) were significant factors associated with wanting more attention to weight loss and nutrition. In addition, there was a significant positive interaction between cachexia and symptoms of mood disorder (p = 0.01), meaning that the effect of cachexia increased with increasing severity of symptoms of mood disorder (Table 4). The sensitivity analysis confirmed the significance of the three former factors and differed only with respect to the significance of the interaction term (data not shown).

Discussion

This study shows that cachexia is a prevalent condition (51% of inpatients and 22% of outpatients) in an unselected sample of Norwegian hospital patients with cancer. A substantial number of patients expressed a need of increased clinical attention to the condition, in particular patients already suffering from cachexia.

Like previous studies, prevalence of cachexia was especially high in gastrointestinal and lung cancer, and lowest in breast cancer and hematologic cancer [12]. Cancer type was the one factor most strongly associated with cachexia, even when adjusting for other relevant factors, such as age, gender, and disease stage.

Interestingly, the prevalence of cachexia was high, not only in patients with metastatic cancer (55% in inpatients and 24% in outpatients) but also in patients with localized (local or locally advanced) cancer (48 and 19%). In the regression analysis, cancer stage did in fact not significantly associate with cachexia.

Other studies support that weight loss can occur early in the cancer trajectory [12, 26]. The reason for this might be related to the cachexia pathophysiology. Inflammation is believed to be a driver of cachexia [27], and Martignoni et al. [28] have shown that inflammatory changes in the liver in patients with pancreatic cancer and cachexia were not associated with presence of liver metastases, however, strongly associated with histopathologic grade. The authors suggest that cancers with certain histopathologic features might be able to invoke systemic inflammation and cachexia independent of tumor size, lymph node involvement, and presence of metastases [28]. This challenges the impression that cachexia mainly is a problem in patients with advanced cancer [5] and signals that cachexia should be assessed early in the cancer trajectory.

Cachexia prevalence was consistently lower in patients with curative treatment intent compared to patients with palliative treatment intent (OR 1.6, p = 0.03), although significance was not maintained in the multivariate model. Given that stage is of little importance to cachexia prevalence in this dataset, the explanation of the difference might be that curable cancers respond better to anti-cancer therapy, and thus cachexia is more effectively treated in these patients. Type of treatment (chemotherapy, radiotherapy, etc.) did not significantly associate with cachexia and prevalence estimates were pointing in different directions for in- and outpatients.

The proportion of patients wanting more clinical attention to weight loss and nutrition was considerable, particularly in patients with cachexia, where one third of patients felt that the issue did not get enough attention. This indicates a sizeable unmet need. Apart from cachexia, the need of more attention was associated with several other factors (Table 3). However, after multivariable adjustment, the only factors still showing an association with a need of more attention were cachexia, symptoms of mood disorder, and gender. This confirms the findings of a previous qualitative study [15] that patients with cachexia do want more attention to their condition. Thus, the fear that health care professionals may have of upsetting these patients with such attention [16] do not seem justified (only 3% of patients with cachexia wanted less clinical attention to the condition). Interestingly, patients with symptoms of mood disorder (36% reported mild, moderate, or severe symptoms, data not shown) also seem to have an increased need of attention to weight loss and nutrition. The reason for this might be that patients unable to eat often suffer mentally due to the loss of the social aspect of eating, conflicts with next of kin regarding food intake, and, ultimately, they may see anorexia as a sign of disease progression and impending death [29]. Male gender was also associated with a request for more attention. Although speculative, one explanation might be that women more often speak out about difficulties related to advanced disease, and thus, get the necessary attention, while men more often keep silent [30].

The implication of these findings to health care professionals is that increased awareness to cachexia and patients’ needs related to the condition is necessary. Awareness seems especially important in patients with early-stage cancer where cachexia may have been assumed less prevalent. Screening using body weight measurement and questions about previous weight loss, food intake, and appetite seems necessary. The PROMs used in this study apt for this purpose. Psychosocial consequences that might follow from anorexia should also be addressed.

On an organizational level, it is important that health care providers responsible for patients with cancer implement guidelines aimed to detect cachexia and malnutrition at all stages of cancer, but especially at early stages where this condition more likely is overlooked. This is an argument for early integration of palliative and oncologic care [31]. By taking a proactive approach to these issues and offer information and palliative care to the patients, one might prevent some of the psychosocial distress that cachexia patients are facing and increase patient satisfaction.

Limitations

This study was conducted within a single region, and thus, the external validity of this study depends on the local organization of cancer care. For example, who are treated as outpatients and who are treated as inpatients might vary. However, the Norwegian health care system is predominantly public, with equal distribution of resources and uniform training and licensing of health care personnel. The population and frequency of diseases are also relatively homogenous. Therefore, the studied population is likely to be representative of every hospital cancer population resembling the Norwegian cancer population. The limited scope of operations also enabled us to approach most of the patients meeting the inclusion criteria within the region, which increases the internal validity of this study.

Another limitation concerns the choice only to include outpatients from the department of medical and radiation oncology. This resulted in an underrepresentation of patients with lung cancer, for whom the responsibility is divided between departments of oncology and internal medicine. Outpatients under surgical oncological care are not represented for the same reason. However, regarding the smaller sample of inpatients, patients from all branches of cancer care are represented. Consequently, there are some differences between outpatients and inpatients other than just provision of care, which is why results have been presented separately or adjustments made in regression analyses.

Objective measures of muscle or fat mass were not used when defining cachexia although sarcopenia is an element in the international consensus definition [1]. However, the definition used is also validated [20] and the main criteria in the two definitions are equal. The possible underestimation of cachexia prevalence that might follow from this is believed to be small; according to a recent publication [32], up to 89% of patients with cachexia are defined cachectic based on weight loss regardless of the presence of sarcopenia. Additionally, while weight loss and BMI are regularly registered in clinical practice, the assessment of sarcopenia necessitates supplementary tests (computed tomography, bioelectrical impedance analysis, etc.). Thus, the definition used in this study might be clinically more applicable.

Regarding treatment type, information was collected only on current treatment modality, and not on previous treatment. Hence, association between cachexia and treatment was based on ongoing treatment and not amount of treatment previously received. For the same reason was one unable to further describe the localized and metastatic cancer stages in terms of number of treatment lines received.

Finally, a study-specific, not previously validated question was used to assess the need for clinical attention to cachexia, so this analysis needs to be viewed as exploratory. In particular, limiting the question to what the physician should focus on, might have underestimated the attention given to nutrition and weight loss by other health care workers.

Conclusion

Cachexia is a prevalent condition, affecting both patients with localized and metastatic cancer. Clinical attention to the condition is a sizeable unmet need, and it is required that health care professionals and health care providers are aware of the problem to ensure proper clinical management, and that the informational and palliative care needs of patients are met.

References

Fearon K, Strasser F, Anker SD, Bosaeus I, Bruera E, Fainsinger RL, Jatoi A, Loprinzi C, MacDonald N, Mantovani G, Davis M, Muscaritoli M, Ottery F, Radbruch L, Ravasco P, Walsh D, Wilcock A, Kaasa S, Baracos VE (2011) Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: an international consensus. The Lancet Oncology 12(5):489–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70218-7

Hinsley R, Hughes R (2007) The reflections you get: an exploration of body image and cachexia. Int J Palliat Nurs 13(2):84–89. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijpn.2007.13.2.23068

McClement S (2005) Cancer anorexia-cachexia syndrome: psychological effect on the patient and family. J Wound, Ostomy, Continence Nurs: Off Publ Wound, Ostomy Continence Nurses Soc/ WOCN 32(4):264–268. https://doi.org/10.1097/00152192-200507000-00012

Ross PJ, Ashley S, Norton A, Priest K, Waters JS, Eisen T, Smith IE, O’Brien ME (2004) Do patients with weight loss have a worse outcome when undergoing chemotherapy for lung cancers? Br J Cancer 90(10):1905–1911. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6601781

Tisdale MJ (2002) Cachexia in cancer patients. Nat Rev Cancer 2(11):862–871. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc927

Farkas J, von Haehling S, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Morley JE, Anker SD, Lainscak M (2013) Cachexia as a major public health problem: frequent, costly, and deadly. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 4(3):173–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13539-013-0105-y

Konishi M, Ishida J, Springer J, Anker SD, von Haehling S (2016) Cachexia research in Japan: facts and numbers on prevalence, incidence and clinical impact. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 7(5):515–519. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.12117

von Haehling S, Anker SD (2014) Prevalence, incidence and clinical impact of cachexia: facts and numbers-update 2014. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 5(4):261–263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13539-014-0164-8

Blum D, Omlin A, Baracos VE, Solheim TS, Tan BH, Stone P, Kaasa S, Fearon K, Strasser F, European Palliative Care Research C (2011) Cancer cachexia: a systematic literature review of items and domains associated with involuntary weight loss in cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 80(1):114–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.10.004

Wallengren O, Lundholm K, Bosaeus I (2013)) Diagnostic criteria of cancer cachexia: relation to quality of life, exercise capacity and survival in unselected palliative care patients. Supportive Care Cancer : Off J Multinatl Assoc Support Care Cancer 21(6):1569–1577. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-012-1697-z

Sun L, Quan XQ, Yu S (2015) An epidemiological survey of cachexia in advanced cancer patients and analysis on its diagnostic and treatment status. Nutr Cancer 67(7):1056–1062. https://doi.org/10.1080/01635581.2015.1073753

Dewys WD, Begg C, Lavin PT, Band PR, Bennett JM, Bertino JR, Cohen MH, Douglass HO, Jr., Engstrom PF, Ezdinli EZ, Horton J, Johnson GJ, Moertel CG, Oken MM, Perlia C, Rosenbaum C, Silverstein MN, Skeel RT, Sponzo RW, Tormey DC (1980) Prognostic effect of weight loss prior to chemotherapy in cancer patients. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Med 69 (4):491–497, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-2918(05)80001-3

Temel JS, Abernethy AP, Currow DC, Friend J, Duus EM, Yan Y, Fearon KC (2016) Anamorelin in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer and cachexia (ROMANA 1 and ROMANA 2): results from two randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trials. The Lancet Oncology 17(4):519–531. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00558-6

Hopkinson JB, Wright DN, McDonald JW, Corner JL (2006) The prevalence of concern about weight loss and change in eating habits in people with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag 32(4):322–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.05.012

Reid J, McKenna HP, Fitzsimons D, McCance TV (2010) An exploration of the experience of cancer cachexia: what patients and their families want from healthcare professionals. Eur J Cancer Care 19(5):682–689. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2354.2009.01124.x

Millar C, Reid J, Porter S (2013) Healthcare professionals’ response to cachexia in advanced cancer: a qualitative study. Oncol Nurs Forum 40(6):E393–E402. https://doi.org/10.1188/13.onf.e393-e402

Schag CC, Heinrich RL, Ganz PA (1984) Karnofsky performance status revisited: reliability, validity, and guidelines. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 2(3):187–193. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1984.2.3.187

Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J, Davis TE, McFadden ET, Carbone PP (1982) Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol 5(6):649–655. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000421-198212000-00014

Buccheri G, Ferrigno D, Tamburini M (1996) Karnofsky and ECOG performance status scoring in lung cancer: a prospective, longitudinal study of 536 patients from a single institution. Eur J Cancer (Oxford, England : 1990) 32a(7):1135–1141

Blum D, Stene GB, Solheim TS, Fayers P, Hjermstad MJ, Baracos VE, Fearon K, Strasser F, Kaasa S, on behalf of E-I (2014) Validation of the consensus-definition for cancer cachexia and evaluation of a classification model—a study based on data from an international multicentre project (EPCRC-CSA). Ann Oncol: Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol/ ESMO 25(8):1635–1642. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdu086

Bauer J, Capra S, Ferguson M (2002) Use of the scored Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA) as a nutrition assessment tool in patients with cancer. Eur J Clin Nutr 56(8):779–785. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601412

Klepstad P, Loge JH, Borchgrevink PC, Mendoza TR, Cleeland CS, Kaasa S (2002) The Norwegian brief pain inventory questionnaire: translation and validation in cancer pain patients. J Pain Symptom Manag 24(5):517–525. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-3924(02)00526-2

Chalder T, Berelowitz G, Pawlikowska T, Watts L, Wessely S, Wright D, Wallace EP (1993) Development of a fatigue scale. J Psychosom Res 37(2):147–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3999(93)90081-P

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Lowe B (2009) An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics 50(6):613–621. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613

Thronaes M, Raj SX, Brunelli C, Almberg SS, Vagnildhaug OM, Bruheim S, Helgheim B, Kaasa S, Knudsen AK (2016) Is it possible to detect an improvement in cancer pain management? A comparison of two Norwegian cross-sectional studies conducted 5 years apart. Support Care Cancer : Off J Multinatl Assoc Support Care Cancer 24(6):2565–2574. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-3064-3

Kritchevsky SB, Wilcosky TC, Morris DL, Truong KN, Tyroler HA (1991) Changes in plasma lipid and lipoprotein cholesterol and weight prior to the diagnosis of cancer. Cancer Res 51(12):3198–3203

Fearon K, Arends J, Baracos V (2013) Understanding the mechanisms and treatment options in cancer cachexia. Nature reviews. Clin Oncol 10(2):90–99. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.209

Martignoni ME, Dimitriu C, Bachmann J, Krakowski-Rosen H, Ketterer K, Kinscherf R, Friess H (2009) Liver macrophages contribute to pancreatic cancer-related cachexia. Oncol Rep 21(2):363–369

Oberholzer R, Hopkinson JB, Baumann K, Omlin A, Kaasa S, Fearon KC, Strasser F (2013) Psychosocial effects of cancer cachexia: a systematic literature search and qualitative analysis. J Pain Symptom Manag 46(1):77–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.06.020

Skulason B, Hauksdottir A, Ahcic K, Helgason AR (2014) Death talk: gender differences in talking about one’s own impending death. BMC Palliative Care 13(1):8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-684x-13-8

Hui D, Kim YJ, Park JC, Zhang Y, Strasser F, Cherny N, Kaasa S, Davis MP, Bruera E (2015) Integration of oncology and palliative care: a systematic review. Oncologist 20(1):77–83. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0312

Blauwhoff-Buskermolen S, Langius JAE, Becker A, Verheul HMW, de van der Schueren MAE (2017) The influence of different muscle mass measurements on the diagnosis of cancer cachexia. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 8(4):615–622. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.12200

Funding

This study has received funding from the Cancer Fund at St. Olav’s Hospital—Trondheim University Hospital and The Liaison Committee for education, research, and innovation in Central Norway. Additionally, the European Palliative Care Research Centre has received unrestricted grants from The Norwegian Cancer Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the regional ethics committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest

Stein Kaasa reports stock ownership in Eir Soloutions AS. Barry Laird reports personal fees from Chugai, outside the submitted work. Ola Magne Vagnildhaug, Trude Rakel Balstad, Sigrun Saur Almberg, Cinzia Brunelli, Anne Kari Knudsen, Morten Thronæs, and Tora Skeidsvoll Solheim have nothing to disclose.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vagnildhaug, O.M., Balstad, T.R., Almberg, S.S. et al. A cross-sectional study examining the prevalence of cachexia and areas of unmet need in patients with cancer. Support Care Cancer 26, 1871–1880 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-4022-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-4022-z