Abstract

Introduction

As the cost of cancer treatment continues to rise, many patients are faced with significant emotional and financial burden. Oncology navigators guide patients through many aspects of care and therefore may be especially aware of patients’ financial distress. Our objective was to explore navigators’ perception of their patients’ financial burden and their role in addressing financial needs.

Materials and methods

We conducted a real-time online survey of attendees at an oncology navigators’ association conference. Participants included lay navigators, oncology nurse navigators, community health workers, and social workers. Questions assessed perceived burden in their patient population and their role in helping navigate patients through financial resources. Answers to open-ended questions are reported using identified themes.

Results

Seventy-eight respondents participated in the survey, reporting that on average 75% of their patients experienced some degree of financial toxicity related to their cancer. Only 45% of navigators felt the majority of these patients were able to get some financial assistance, most often through assistance with medical costs (73%), subsidized insurance (36%), or non-medical expenses (31%). Commonly identified barriers for patients obtaining assistance included lack of resources (50%), lack of knowledge about resources (46%), and complex/duplicative paperwork (20%).

Conclusion

Oncology navigators reported a high burden of financial toxicity among their patients but insufficient knowledge or resources to address this need. This study underscores the importance of improved training and coordination for addressing financial burden, and the need to address community and system-level barriers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cancer care costs have increased dramatically in recent years, outpacing the growth in US gross domestic product and non-cancer healthcare costs. [1] Although much of the existing literature has focused on the unsustainability of rising cancer care costs for the healthcare system and for societal economic stability, the rising cost of cancer care has also caused substantial, and in many cases, catastrophic, financial damage to individual cancer patients and their caregivers [2,3,4]. Twenty to 48% of cancer patients report significant and worrisome financial burden due to their cancer treatment, and individuals with cancer are 2.6 times more likely to declare bankruptcy than the general population [3, 5, 6]. Cancer-related financial hardship, otherwise known as financial toxicity, has been associated with distress, anxiety, overall worse health-related quality of life, cancer treatment non-adherence, and higher mortality [6,7,8,9,10]. Cancer-related financial hardship also differentially affects underserved populations, such as racial/ethnic minorities and the publicly insured, and thus has the potential to exacerbate existing racial/ethnic and insurance-related disparities in cancer outcomes [3, 11].

Navigating the financial aspects of the cancer experience is a specific challenge for patients that are not well addressed in most oncology care environments [12]. Cancer navigation services have emerged across the country to help direct and support patients through the cancer clinical experience, and as a result, many navigators have become the default support team member tasked with, or fielding questions about, financial assistance services when financial toxicity becomes a problem for patients.

Directed navigation of patients through the cancer care process has increasingly been recognized as an important mechanism to improve coordination of cancer care services, provide information, and support to patients and their families, reduce delays in detection and treatment, reduce costs and emergency department visits, and enhance the quality and outcomes of cancer care [13,14,15,16,17]. Despite recommendations to address financial needs as a routine part of survivorship care [18, 19], clinical and lay navigators may not be well-equipped to provide financial advice. Oncology navigators are typically employed within the cancer hospital or health system and may include nurses, social workers, or lay navigators who typically receive training focused on the supportive care needs of patients and how to access available resources, such as appointment scheduling and logistics, managing symptoms, and accessing psychosocial support [20]. Navigators guide patients through the multiple phases and complexities of the cancer experience, including screening and diagnosis, surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and other treatment; navigators also may assist with palliative and end-of-life care. Navigators typically have little to no specialized training regarding financial counseling or financial assistance, yet, because of their ongoing relationships with patients, are often the first point of contact for addressing financial needs.

Although several studies have reported on the extent, sources, and outcomes of cancer-related financial toxicity among patients [2, 3, 7, 10, 21] and previous work has explored provider and payer perceptions of financial burden [22], no studies, to our knowledge, have reported on the role of oncology navigators in helping patients to cope with cancer-related financial hardship. Our objective was to understand oncology navigators’ perspectives about their patients’ cancer-related financial burden and to identify gaps in accessing financial assistance for uninsured and underinsured patients with cancer.

Methods

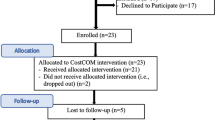

We surveyed attendees of a regional oncology navigators’ association conference held in Chapel Hill, NC, in June 2016. Participants included nurse navigators, lay navigators, community health workers, community advocates representing non-profits organizations, and social workers, all of whom provided oncology navigation services and attended the one-day conference. As all of these attendees were involved in some aspect of oncology navigation; we refer to them collectively as “navigators”. Attendees were asked to complete a brief, electronic, audience participation survey. Survey questions assessed their perceptions of patients’ cancer-related financial burden and access to financial support resources to pay for cancer care. This study was reviewed and determined to be research exempt by the Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC-CH) (IRB# 16-1775).

Participant recruitment

Criteria for survey participation included (1) attendance at the navigation conference, (2) current work responsibilities including assisting cancer patients with access to cancer support resources, (3) ability to read and understand English, and (4) access to a smart phone, tablet or laptop computer. The principal investigator (SBW) and study coordinator (MLM) were present at the conference to announce the study, explain consent procedures, and offer the opportunity for participation. They explained the purpose of the study as well as the online survey process. Because the survey was taken anonymously by personal smart phone, tablet, or laptop computer, conference attendees were unaware of others’ survey responses, and survey participation had no effect on conference participation. Participants self-reported their role working with cancer patients.

Survey technology

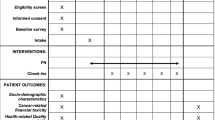

The Poll Everywhere online platform was chosen for survey administration due to its ease of use and the research staff’s familiarity with the technology. The survey consisted of five questions with a mixture of both multiple choice and open-ended text responses. Participants could only register a single response per question, but for open-ended questions they could list several answers within one response. Survey questions were designed to capture a variety of financial assistance variables within a short time frame (approximately 5 min total). See Table 1 for a list of survey questions.

Respondents were given two options for survey participation: texting responses, or going online to a designated webpage and answering the questions as they appeared on the conference screen slideshow. Participants completed the survey on personal mobile devices, and the total number of completed responses (but not response content) was displayed in real time on the conference screen, enabling study staff to gauge the number of participant responses and when to move to the next “poll” or question.

In addition to the Poll Everywhere survey completed during the patient navigation conference, conference attendees were given a chance to comment on the issue of financial burden by completing an evaluation survey post-conference. Specifically, one question on the evaluation survey asked, “If you could make one improvement to the system that would improve your patients’ financial experience with cancer, what would it be?” This question was asked in both settings, but as overall themes did not differ widely from Poll Everywhere to the post-conference survey, we report the answers from the post-conference survey only.

Data analysis

Poll Everywhere survey responses were downloaded for review and analysis. Answers to multiple choice questions were described with frequencies. Answers to open-ended questions were categorized qualitatively according to theme. After a preliminary review of responses, salient themes in each open-ended question were identified by the research team. Two coders (JS and MLM) then independently reviewed responses and sorted each into textual units or themes, with disagreements resolved by the full study team. Participants could include multiple answers within a single free text response, so some responses were identified as containing more than one theme. Table 2 contains representative quotes for each identified theme. The same process of analysis was performed with responses to the conference evaluation question regarding one improvement to the system to alleviate cancer-related financial burden.

Results

Out of a total of 148 registered conference participants, 78 navigators attended the session and participated in the conference survey and 81 responded to the post-conference survey by email, for an overall response rate of 53% (in person) and 55% (email).

Overall, navigators reported a high prevalence of financial distress among their patients, reporting on average that 75% of their patients experienced financial toxicity related to their cancer (interquartile range 65%–90%). Additionally, 12% of navigators reported that 100% of their patients experience cancer-related financial distress. In terms of their patients requiring financial assistance, 45% of respondents indicated that most are able to get some type of financial assistance, 26% said most are unable to get any assistance, and 29% reported being unsure whether their patients were able to access any type of financial assistance.

The most common type of financial assistance reported was assistance with medical costs (73%), with half of these responses specifically referencing medication or prescription drug assistance programs. Other forms of medical cost assistance that were reported included references to hospital-based charity care and copay assistance. In addition to programs that cover portions of medical costs directly, common sources of support included assistance in applying for Medicaid or insurance subsidies (36%), assistance with non-medical costs such as transportation or lodging (31%), and financial counseling (13%). Nine percent of respondents reported that they were unsure of what type of financial assistance their patients received.

Navigators were also asked to describe one or more obstacles preventing their patients from accessing financial assistance. Half of all respondents mentioned concerns regarding insufficient resources or patient ineligibility for existing resources. These included concerns specific to rural areas, patients without citizenship, the underinsured, and patients with incomes above specific program thresholds. Navigators also expressed that both patients and providers lacked knowledge and awareness about existing financial assistance programs (47%). When patients and caregivers were aware of financial assistance resources for which they might qualify, navigators reported that patients faced significant barriers during the application process. Among respondents reporting that application complexity was a barrier (20%), specific challenges included collecting needed documentation, navigating online application forms, and engaging in unnecessary or duplicative effort. Issues related to patient/provider communication made up 20% of responses and included several dimensions of communication challenges. Respondents acknowledged challenges on the patient side—such as “patients don’t share distress”, “hate to ask for assistance” or “embarrassment”—as well as challenges on the navigator’s side—such as “having too many patients and not able to screen everyone”. Lastly, respondents noted language and literacy (11%) as a barrier to accessing assistance.

Finally, navigators were asked to suggest one improvement to the system that would improve patient’s financial experience. Many navigators offered more than one suggestion for improving the system; however, the two most common (and thematically related) suggestions were increasing the number of navigators specifically trained to assist with financial concerns (34%), followed by increasing patient/provider communication about financial need (32%). In terms of the latter suggestion, navigators specifically recommended adding a screening tool to assess financial distress early and then periodically monitoring financial distress throughout the cancer care process. Other recommendations focused on reducing overall patient cost (26%), increasing coordination and centralizing information about financial assistance programs (24%), and implementing health insurance reforms (13%), such as moving to a single-payer or other universal healthcare system and simplifying patient costs through bundled charges. Less common responses (15%) included reducing billing errors, increasing transportation funding, and developing community education initiatives on the cost of cancer care.

Discussion

There is a growing appreciation for the scope and consequences of cancer-related financial toxicity [23,24,25]. While previous studies have examined cancer patient or oncologist perspectives on the financial consequences of cancer and its treatment [4, 22, 23, 25], few, if any, have assessed oncology navigators’ perception of financial need and available resources. In this study, we surveyed cancer navigators to gain their perspectives on the financial hardships facing their patients and recommendations for addressing this need.

Navigators in this sample reported that their patients experienced a high burden of financial distress. Importantly, less than half of navigators indicated that their patients received adequate financial assistance despite awareness of patient need by the navigators, suggesting that screening alone may not be sufficient to alleviate distress. Navigators identified barriers to financial assistance on multiple levels (Fig. 1). At a system and community level, there is limited and unstable availability of financial resources, often with eligibility linked to cancer type or severity, citizenship status, or income level. At the clinic level, navigators reported poor patient and provider knowledge of resources and limited communication between patients and providers about the issue of financial toxicity. Navigators also cited the complexity of the financial assistance application process and fragmentation of financial assistance services as major barriers to effective assistance. Other research has documented low rates of referral to medication assistance programs [26], which may be partly due to high variability in the referral and application process between programs [27, 28]. Overall, the perspective of navigators was that implementing systematic screening and monitoring of cancer-related financial toxicity, increasing the financial assistance resources available, providing better information about these resources to patients and providers, and decreasing the complexity of the application process, are all necessary steps to improve the navigation of patients through the financial assistance process and patients’ cancer care experience.

Because communication challenges (e.g., discomfort discussing care costs with patients, insufficient time to engage in cost discussions) were also mentioned as barriers to patients’ receipt of financial assistance services, it will be important to equip providers with effective screening tools and efficient strategies for engaging patients in routine discussions regarding cancer-related financial concerns and available financial support services, and to investigate clinical resources in addition to medical providers that can respond effectively to screening results, while ensuring patient confidentiality, trust, and confidence in the process [2, 4, 12, 29].

Participating navigators highlighted the need for specialized training in financial support resources and information, which is not routinely provided. Developing a financial toxicity training module for navigators and other cancer support staff to use to identify, monitor, and inform patients in need of financial assistance is therefore warranted.

Collectively, these findings underscore the need for more systematic delivery of financial assistance services, and point to the potential to use navigators as a motivated and informed resource to guide patients through the referral and application process. A 2014 study that assessed perceptions among navigators of patient concerns regarding employment concerns also found navigators reported a desire for more training and for earlier assessment of patient need. [30] A coordinated system would involve screening during an early oncology care visit, with navigators or other staff trained to follow up with patients to assess financial need and eligibility and connect them to existing resources. This model would address the system changes recommended by our navigators and is consistent with recommendations for more patient-centered supportive cancer care services [19].

There are several limitations to this study worth noting. First, study participants were limited to a sample of oncology patient navigators who were recruited using a convenience sampling approach. While these participants represented a variety of large and small practice types in rural and urban areas of the Southeastern US, their perspectives may not be generalizable on a national level due to geographic differences in patient need, including state differences in Medicaid expansion and oral chemotherapy parity legislation. Finally, this study only describes the views of navigators. Further examination into other types of providers’ experiences may highlight a different set of facilitators and barriers than those discussed here.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to survey oncology navigator perspectives on patient financial distress and the adequacy and challenges of financial assistance services. Given that patient navigators often engage patients in discussions regarding myriad treatment-related barriers and needs, navigators are ideally positioned to provide initial insights regarding the extent and management of financial distress among cancer patients. We are now leveraging findings from this study to conduct a more in-depth financial distress and financial assistance survey in a large and diverse cohort of oncology providers throughout the US Future work in cancer-related financial toxicity should seek to optimize financial distress monitoring, provide specialized financial training to oncology care support staff, more systematically identify and link patients to financial assistance resources, and evaluate the role of new policies to reduce the financial burden of cancer care in improving patients’ quality of life and cancer care experience.

References

Macready N (2011) The climbing costs of cancer care. J Natl Cancer Inst 103:1433–1435. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djr402

Bestvina CM, Zullig LL, Yousuf Zafar S (2014) The implications of out-of-pocket cost of cancer treatment in the USA: a critical appraisal of the literature. Future Oncol 10:2189–2199. https://doi.org/10.2217/FON.14.130

Yabroff KR, Dowling EC, Guy GP, Banegas MP, Davidoff A, Han X, Virgo KS, McNeel TS, Chawla N, Blanch-Hartigan D, Kent EE, Li C, Rodriguez JL, De Moor JS, Zheng Z, Jemal A, Ekwueme DU (2016) Financial hardship associated with cancer in the United States: findings from a population-based sample of adult cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.62.0468

de Souza JA, Wong Y-N (2013) Financial distress in cancer patients. J Med Person 11.2:73–77

Zafar SY et al (2014) Population-based assessment of cancer survivors' financial burden and quality of life: a prospective cohort study. J Oncol Pract 11.2:145–150

Ramsey S et al (2013) Washington State cancer patients found to be at greater risk for bankruptcy than people without a cancer diagnosis. Health Aff 32.6:1143–1152

Chongpison Y, Hornbrook MC, Harris RB, Herrinton LJ, Gerald JK, Grant M, Bulkley JE, Wendel CS, Krouse RS (2016) Self-reported depression and perceived financial burden among long-term rectal cancer survivors. Psychooncology. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3957

Kale HP, Carroll NV (2016) Self-reported financial burden of cancer care and its effect on physical and mental health-related quality of life among US cancer survivors. Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29808

Nekhlyudov L, Madden J, Graves AJ, Zhang F, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D (2011) Cost-related medication nonadherence and cost-saving strategies used by elderly Medicare cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv 5:395–404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-011-0188-4

Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, Blough DK, Overstreet KA, Shankaran V, Newcomb P (2016) Financial insolvency as a risk factor for early mortality among patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.64.6620

Jagsi R, Pottow JAE, Griffith KA, Bradley C, Hamilton AS, Graff J, Katz SJ, Hawley ST (2014) Long-term financial burden of breast cancer: experiences of a diverse cohort of survivors identified through population-based registries. J Clin Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.53.0956

Smith SK, Nicolla J, Zafar SY (2014) Bridging the gap between financial distress and available resources for patients with cancer: A qualitative study. J Oncol Pract 10.5:e368–e372

Tan CHH, Wilson S, McConigley R (2015) Experiences of cancer patients in a patient navigation program: a qualitative systematic review. JBI Database Syst Rev Implement Rep 13:136–168. 10.11124/jbisrir-2015-1588

Krok-Schoen JL, Oliveri JM, Paskett ED (2016) Cancer care delivery and women’s health: the role of patient navigation. Front Oncol 6:2. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2016.00002

Johnson F (2015) Systematic review of oncology nurse practitioner navigation metrics. Clin J Oncol Nurs 19:308–313. https://doi.org/10.1188/15.CJON.308-313

Rocque GB, Pisu M, Jackson BE, Kvale EA, Demark-Wahnefried W, Martin MY, Meneses K, Li Y, Taylor RA, Acemgil A, Williams CP, Lisovicz N, Fouad M, Kenzik KM, Partridge EE (2017) Resource use and Medicare costs during lay navigation for geriatric patients with cancer. JAMA Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.6307

Rodday AM et al (2015) Impact of patient navigation in eliminating economic disparities in cancer care. Cancer 121.22:4025–4034

Runowicz CD, Leach CR, Henry NL, Henry KS, Mackey HT, Cowens-Alvarado RL, Cannady RS, Pratt-Chapman ML, Edge SB, Jacobs LA, Hurria A, Marks LB, LaMonte SJ, Warner E, Lyman GH, Ganz PA (2016) American Cancer Society/American Society of Clinical Oncology Breast Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline. J Clin Oncol 34:611–635. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.64.3809

Page AEK, Adler NE eds. (2008) Cancer care for the whole patient: Meeting psychosocial health needs. National Academies Press

Cantril C, Haylock PJ (2013) Patient navigation in the oncology care setting. Semin Oncol Nurs 29:76–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2013.02.003

Zafar SY et al (2013) The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: a pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient's experience. The oncologist 18.4:381–390

Zafar SY, Newcomer LN, McCarthy J, Fuld Nasso S, Saltz LB (2017) How should we intervene on the financial toxicity of cancer care? One shot, four perspectives. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ book Am Soc Clin Oncol Meet 37:35–39. 10.14694/EDBK_174893

Zafar Y (2016) Financial toxicity of cancer care: It’s time to intervene. JNCI: J Natl Cancer Inst 108.5

Souza JA et al (2017) Measuring financial toxicity as a clinically relevant patient‐reported outcome: The validation of the COmprehensive Score for financial Toxicity (COST). Cancer 123.3:476–484

O’Connor J, Kircher S, de Souza J (2016) Financial toxicity in cancer care. J Community Support Oncol 14:101–106. https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0239

Harris JK, Cyr J, Carothers BJ, Mueller NB, Anwuri VV, James AI (2011) Referrals among cancer services organizations serving underserved cancer patients in an urban area. Am J Public Health 101:1248–1252. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2010.300017

Choudhry NK, Lee JL, Agnew-Blais J, Corcoran C, Shrank WH (2009) Drug company-sponsored patient assistance programs: a viable safety net? Health Aff (Millwood) 28:827–834. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.827

Schwieterman P (2015) Navigating financial assistance options for patients receiving specialty medications. Am J Health Syst Pharm 72:2190–2195. https://doi.org/10.2146/ajhp140906

Mathews M, Buehler S, West R (2009) Perceptions of health care providers concerning patient and health care provider strategies to limit out-of-pocket costs for cancer care. Curr Oncol 16.4:3

Vanderpool RC, Nichols H, Hoffler EF, Swanberg JE (2017) Cancer and employment issues: perspectives from cancer patient navigators. J Cancer Educ 32:460–466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-015-0956-3

Funding

Funding for this project was provided through the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and Pfizer Independent Grants for Learning & Change (PI: Wheeler and Rosenstein). Ms. Sellers reports payment as a consultant with Pfizer which was unrelated to the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None of the above authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose, beyond receiving independent grant funding from Pfizer. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Results of this study have not been published or presented previously.

Human subjects

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Spencer, J.C., Samuel, C.A., Rosenstein, D.L. et al. Oncology navigators’ perceptions of cancer-related financial burden and financial assistance resources. Support Care Cancer 26, 1315–1321 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3958-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3958-3