Abstract

Purpose

Fatigue is a troublesome symptom for breast cancer patients, which might be mitigated with exercise. Cancer patients often prefer their oncologist recommend an exercise program, yet a recommendation alone may not be enough to change behavior. Our study determined whether adding an exercise DVD to an oncologist’s recommendation to exercise led to better outcomes than a recommendation alone.

Methods

Ninety breast cancer patients, at varying phases of treatment and stages of disease, were randomized to receive the following: an oncologist verbal recommendation to exercise (REC; n = 43) or REC plus a cancer-specific yoga DVD (REC + DVD; n = 47). Fatigue, vigor, and depression subscales of the Profile of Mood States, and physical activity levels (MET-min/week), exercise readiness, and self-efficacy were assessed at baseline, 4, and 8 weeks. Analyses controlled for age, time since diagnosis, and metastatic disease.

Results

Over 8 weeks, women in REC + DVD used the DVD an average of twice per week. The REC + DVD group had greater reductions in fatigue (− 1.9 ± 5.0 vs. − 1.0 ± 3.5, p = 0.02), maintained exercise readiness (− 0.1 ± 1.1 vs. − 0.3 ± 1.3; p = 0.03), and reported less of a decrease in physical activity (− 420 ± 3075 vs. − 427 ± 5060 MET-min/week, p = 0.06) compared to REC only.

Conclusions

A low-cost, easily distributed, and scalable yoga-based DVD could be a simple booster to an oncologist’s advice that motivates breast cancer patients, even those with advanced disease and/or in treatment, to engage in self-care, e.g., exercise, to manage fatigue.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03120819

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Exercise can be an effective self-management strategy to control cancer treatment-related symptoms, such as fatigue [1,2,3]. Controlled trials in women with breast cancer consistently show that exercise lessens treatment-related fatigue [4, 5]. Despite the benefit and safety of exercise for cancer survivors during and after diagnosis, few actually meet the level recommended in guidelines [6] and nearly one-third fail to engage in any leisure-time physical activity [7]. Oncologists have the potential to facilitate behavior change both during and after cancer treatment since cancer survivors state that they prefer to receive exercise information from their oncologist and would be motivated to exercise if their oncologist recommended it [8,9,10]. While most oncologists acknowledge the benefits of exercise for patients, many cite a lack of knowledge and time to talk about exercise and a concern about recommending exercise during treatment as barriers to providing detailed consultation [9, 11,12,13,14]. Whether or not a simple exercise recommendation made by an oncologist during a clinical visit is enough to change patient behavior remains unclear [15].

Exercise need not be vigorous in order to reduce fatigue, as low-intensity programs such as yoga are effective [16,17,18,19,20,21] and could scale to women across stages of disease and phases of treatment. Yoga is appropriate for home-based exercise given relatively low risk of injury or adverse events and may thus be more feasible for patients with limited access or motivation to participate in supervised programs. A low-intensity yoga program could also provide a first step toward positive behavior change to attain recommended levels of physical activity and participation in other types of exercise (e.g., aerobic and/or resistance training) [22, 23]. The primary aim of this study was to determine whether or not adding a breast cancer-specific instructional yoga DVD to a brief oncologist’s recommendation to exercise could reduce fatigue more than a provider recommendation to exercise alone in breast cancer patients. A secondary aim was to determine the additional benefit of providing an instructional DVD to improve mood states (i.e., anxiety, depression) and readiness and self-efficacy for exercise.

Methods

Sample

The target sample for this study was women diagnosed with breast cancer and under an oncologist’s care. Inclusion criteria were the following: 18+ years old, diagnosis of breast cancer, scheduled for a clinical appointment with a surgical, radiation, or medical oncologist at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU), capable of answering survey questions by phone, and cleared to participate in low-intensity exercise by their oncologist. The study was approved by the OHSU Institutional Review Board and all patients provided verbal consent prior to participating in study activities.

Design and procedures

We conducted a randomized, single-blind parallel group controlled trial comparing (1) an oncologist’s verbal recommendation to exercise + standard materials about exercise (REC) to (2) an oncologist’s verbal recommendation to exercise + standard materials + an instructional exercise DVD (REC + DVD). Potential participants were identified by an electronic database of scheduled oncology appointments over a 3-month period and providers were informed daily by study staff about eligible patients to approach during their clinical appointment. The oncologist obtained verbal consent and consenting patients then received a standard recommendation for exercise by the oncologist. After the patient visit, research staff contacted consented patients by phone to provide full study details, confirm eligibility, and obtain baseline data. Staff then mailed a study packet containing materials relevant to the patient’s group assignment. Group assignments were determined by a random numbers table and placed in sealed, sequentially numbered packets mailed to participants in the order that they initially enrolled. The oncologists were blinded to the study randomization and assignment; however, study staff administering follow-up surveys were not blinded to group assignment for follow-up because of the need to ask questions about DVD usability for women assigned to that group. Follow-up data were collected by telephone at 4 and 8 weeks post-enrollment using standardized questionnaires to assess study outcomes.

Interventions

Provider recommendation + standard published materials (REC)

Medical providers in this study provided a standardized brief recommendation for exercise to a consenting patient during a clinical visit. The script for oncologists was as follows:

As your oncologist, I believe that you are healthy enough to engage in low intensity exercise. Recent research has shown that exercise is safe and tolerable both during and after cancer treatments. Some of the side effects you may have experienced from cancer and cancer treatments may be controlled with regular exercise. I recommend that you consider beginning to increase your exercise to meet the guidelines for women with cancer or to continue your exercise program if you are already doing so.

Patients randomized to REC received a packet that contained a study information sheet and standard published exercise information materials. The standard materials consisted of publicly available exercise recommendations for cancer survivors from the American Cancer Society (ACS) [24] and for all adults from the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) [25]. The packet of exercise information was intended to represent general information about exercise and cancer that would be readily available to patients through the internet, a medical clinic, or cancer support services.

Provider recommendation + standard published materials + instructional yoga DVD (REC + DVD)

Participants in the REC + DVD received the same oncologist’s recommendation and written materials as REC and also received an instructional yoga DVD. Inclusion of the video was intended to provide patients with a tool for following the oncologist’s exercise recommendation. The instructional video contained a brief introduction from a breast cancer survivor, who was also featured in the exercise portion of the DVD, and safety information about lymphedema from a lymphedema therapist. The exercise program was a 30-min, low-intensity, restorative yoga program to improve whole body flexibility and to be safe for participants who were in active treatment for cancer and/or who had metastatic disease. The program featured one certified exercise instructor performing the program at a low intensity and two participants demonstrating different modifications either (1) sitting on a therapeutic exercise ball or (2) sitting on a chair for participants unable to perform the exercises from a standing position and/or perform floor-based exercises. The DVD also contained an optional shorter, advanced yoga program for women who were already physically active. Women were encouraged to use the DVD at least three times per week.

Measures

Fatigue and other mood states

The primary outcome for this study was fatigue in the last 7 days, measured by the brief Profile of Mood States (POMS-B) suitable for patients with chronic illness or recovering from surgery [26] and used in studies of cancer survivors [27, 28]. Secondary outcomes for this study were tension, depression, and vigor, since each may be improved with exercise. Respondents rate each item on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all” to “extremely,” and scores are summed where higher scores reflect more vigor and lower scores less tension, depression, and fatigue.

Stage of change for exercise

Stage of change for exercise was measured using The Physical Activity Stage Assessment instrument [29] that was developed for the NIH Behavior Change Consortium studies and reflects the readiness of a person to initiate and maintain behavior change [30], including cancer survivors [31]. The behavior change of interest for this study was regular participation in exercise, defined as equal to 30-min or more of moderate-intensity exercise, at least 5 days per week. Participants chose one of the five statements describing their readiness to change their exercise behavior on a continuum from 1 to 5 where 1 = precontemplation, 2 = contemplation, 3 = preparation, 4 = action, and 5 = maintenance, with higher scores indicating greater readiness.

Self-efficacy for exercise

Self-efficacy describes a person’s belief that they are capable of performing a specific behavior [32]. We measured self-efficacy for exercise using a six-item questionnaire [33, 34] with responses ranging from 1 (not at all confident) to 5 (completely confident) that a person is confident she can engage in exercise even when other things get in the way (e.g., weather, stress, time). Summed scores range from 6 to 30 with higher scores indicating higher self-efficacy.

Physical activity

Physical activity in the past 7 days was evaluated with the International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short-form (IPAQ-short) [35], a seven-item valid and reliable instrument and used to assess physical activity in cancer survivors [36]. The IPAQ determines the average time spent in walking, moderate-intensity, and vigorous-intensity physical activity per week to derive total energy expenditure from physical activity (MET-min/week).

Acceptability and adherence

Usefulness of the oncologist’s recommendation to exercise was rated by all participants using a 5-point Likert scale with 1 = not helpful to 5 = very helpful, while usefulness of the DVD was completed by participants in the REC + DVD group using the same scale. At 8 weeks, the REC + DVD group was asked if they used the DVD at all and if so, how often they exercised using the DVD each week.

Sample size determination and analysis

The sample size for the study was based on the primary outcome of fatigue. With a power = 0.8 and experiment-wise error rate of 0.05, we needed 45 participants per study arm to detect a moderate effect size (d = 0.6) [37]. To account for a potential 10% dropout over 8 weeks, we aimed to enroll 100 women into the trial. An intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis was performed to identify significant group × time interactions using mixed-design model analysis of covariance (MD-ANCOVA). In cases with missing data, the last observation was carried forward to the subsequent time point(s). Planned covariates included the presence of metastatic disease and any significant group differences in participant characteristics or outcomes at baseline. We also performed a per protocol analysis using data from participants with complete baseline and 8-week data to evaluate intervention effects on participants who completed the study.

Results

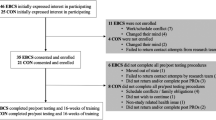

Ninety-five breast cancer survivors verbally consented to participate and received the oncologist’s recommendation to exercise (Fig. 1); however, when contacted to confirm eligibility, complete baseline questionnaires, and receive their assigned study packet, 5 women declined further participation. Thus, 90 women were eligible and received the experimental or control condition after completing baseline questionnaires: REC (n = 43) or REC + DVD (n = 47). Participants were mostly white, non-Hispanic, college educated, currently or formerly employed, and married (Table 1). Women self-reported an average of 2974 MET-min of physical activity per week, or the equivalent of brisk walking about 1.4 h per day. On average, women were 3–5 years past diagnosis, most (50–62%) had localized (stages 0–II) disease, and approximately 17% were in radiation therapy or chemotherapy at enrollment. Women randomized to REC + DVD were significantly older and further past cancer diagnosis than women in REC; thus, these variables were included in subsequent analyses (Table 2). Out of the 90 women completing baseline measures, 84 completed follow-up assessments at 8 weeks (93% retention). Women assigned to REC rated their oncologist’s recommendation to exercise as somewhat to moderately helpful, while women in REC + DVD rated the recommendation as moderately helpful (Table 3). Among women in REC + DVD, 75% watched the DVD included in their study materials and reported exercising to it an average of 1.8 times per week over the 8-week study period. Women in this group rated the DVD as moderately to very helpful, which was higher than how they rated the oncologist’s recommendation alone.

Women in both groups improved on all mood subscales over time, with REC + DVD improving more than REC (Table 2). Group × time interactions were only significant for fatigue, where REC + DVD reported a 50% greater reduction in fatigue than REC, independent of age, time since diagnosis, and presence of metastatic disease (p = 0.02). Over 8 weeks, women in both groups reduced their physical activity levels, but REC + DVD reported less of a decline than REC only (p = 0.06), with group differences becoming significant after excluding study dropouts (p = 0.04). Women in REC + DVD increased their self-efficacy for exercise compared to decreases in REC only, but group differences were not significant. Women in REC group declined in exercise readiness from action to contemplation which was significantly different from women in REC + DVD who maintained their stage of change in the contemplation phase (p = 0.03).

Discussion

Our trial is the first to report that supplementing an oncologist’s verbal recommendation to exercise with a home exercise DVD can lead to better symptom management than a recommendation alone. Though our trial focused on exercise as a strategy to manage cancer treatment-related symptoms, we also found that women receiving the DVD maintained their exercise readiness and that receipt of the DVD tended to buffer the declines in physical activity reported by all women. Breast cancer survivors report fatigue, pain, depression, and lack of motivation, time, access, and worry about safety and “fear of overdoing it” as barriers to exercise [38, 39]. This home-based yoga program tailored for women with breast cancer was designed to reduce barriers of access, time, transportation, and cost. The low-intensity, modifiable yoga-based program addressed concerns about safety and exercise ability and targeted the fatigue that patients cite as reason they do not exercise. Seventy-five percent of participants utilized the DVD at least once and women averaged twice weekly practice over 8 weeks. Eight weeks after receiving their oncologist’s advice to exercise and a DVD, these patients reported twice the reduction in fatigue as women getting advice only. Though the level of improvement in fatigue among women receiving the DVD was modest, it approached the minimally important difference for this fatigue measure [40] and was consistent with the degree of improvement in fatigue reported in other studies of yoga practice [16,17,18,19,20,21]. In contrast to other studies in cancer survivors where yoga sessions are supervised or a mix of supervised with home-based sessions, ours is the first to test a strictly home-based program. To allow for varying participant tolerance for exercise, we incorporated three different levels of instruction into the DVD ranging from very low-intensity yoga, chair-based yoga, and standard yoga practice. Fatigue levels are known to vary from day to day, particularly among patients in active treatment [41]; therefore, allowing women to choose the appropriate intensity of her practice within a single session may have helped women adhere to a regular routine.

Though our study focused on yoga as a strategy to manage fatigue, we were also interested in whether it might increase a patient’s interest in and ability to engage in other types of exercise. To our knowledge, only two other controlled trials have investigated the impact of oncologists’ advice to exercise on short-term physical activity participation in breast cancer patients. Lee et al. reported that an oncologist’s recommendation alone modestly increased exercise levels over 5 weeks among newly diagnosed breast cancer patients [13]. In contrast, Park et al. reported that an oncologist’s exercise recommendation alone was not enough to change physical activity unless it was accompanied by resources for exercise (e.g., instructional DVDs, exercise logs, pedometers, and education) in post-treatment, early stage breast and colorectal cancer survivors [15]. Among our sample of women in various phases of oncology care and stages of disease, physical activity levels declined but significantly less so among women who received the DVD. Fatigue and lack of motivation are often cited by survivors as reasons for avoiding physical activity; thus, it is possible that lowering fatigue through yoga helped mitigate reductions in other types of exercise, albeit the effect was relatively small. Women who received the DVD reported that they remained ready to engage in a regular exercise program, whereas women receiving an oncologist’s advice only became less motivated to do so over time. Thus, it is possible that women practicing yoga would begin to engage in more exercise as their symptoms are better controlled.

Notable strengths of our study included the simplicity and low cost of the intervention, the small burden placed on oncologists to deliver the intervention, strong retention and adherence rates, and the generalizability of our findings to breast cancer patients at any stage of cancer or phase of treatment. Our study also had limitations including a modest sample, the use of self-report rather than objectively measured physical activity, and the short duration of the intervention. We designed this study to be integrated into the multi-disciplinary breast cancer clinic workflow and to be simple for patient participation; therefore, we accepted tradeoffs in order to reduce demand on clinic staff and oncologists’ time and avoid the need for patients to come in for separate study visits. Our intervention length was similar to most other trials of yoga for cancer survivors, though a longer follow-up would have allowed us to evaluate long-term effects of the DVD and whether it may prolong the impact of provider advice. In addition, future studies should consider including an objective measure of physical activity rather than self-report, which is prone to over-reporting and bias. A recent systematic review of the sIPAQ instrument used in our study found that it overestimated physical activity by an average of 84% compared to objective measures [42]. This methodological limitation could explain both the high overall level of physical activity reported by women in our sample, particularly at baseline, and the unexpected declines in physical activity over the study period since few women were in active cancer treatment at the time of enrollment when women are more likely to become inactive.

Cancer-related fatigue is a common and debilitating symptom for cancer patients and is associated with higher rates of disability and depression, lower levels of health-related quality of life, difficulty returning to work, and lack of motivation for exercise, even many years after initial treatment [43, 44]. The intent of our program was to use the oncologist to encourage exercise for symptom management regardless of a patient’s phase of treatment or stage of disease. Cancer patients prefer to receive exercise advice from their oncologist and are more likely to engage in exercise if it is endorsed by their oncologist, yet estimates show that upwards of 84% of oncologists do not provide exercise advice to their patients [45]. Barriers reported by oncologists for prescribing exercise include institutional (lack of time, lack of resources for referral), professional (lack of exercise knowledge), and patient concerns (lack of access, side effects, motivation, health complexity). We reduced the oncologist’s time to deliver the intervention to a small fraction (~ 1–2 min) of a clinic visit by providing a brief script for the oncologist and subsequently mailing patients an exercise DVD. A yoga-based DVD, that was low-intensity and provided varying levels of effort, also removed concerns for oncologists around patient safety, specific exercise knowledge, and lack of resources. This DVD gave patients a tangible, accessible resource that nearly any woman could use to follow her oncologist’s advice. This simple combination of brief advice by an oncologist and a DVD could be easily integrated into routine oncology care and have a meaningful impact on patient health.

References

Courneya KS (2010) Efficacy, effectiveness, and behavior change trials in exercise research. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 7:81

McNeely ML, Campbell KL, Rowe BH, Klassen TP, Mackey JR, Courneya KS (2006) Effects of exercise on breast cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ 175(1):34–41

Courneya KS, Segal RJ, Mackey JR, Gelmon K, Reid RD, Friedenreich CM et al (2007) Effects of aerobic and resistance exercise in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 25(28):4396–4404

Brown JC, Huedo-Medina TB, Pescatello LS, Pescatello SM, Ferrer RA, Johnson BT (2011) Efficacy of exercise interventions in modulating cancer-related fatigue among adult cancer survivors: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 20(1):123–133

McNeely ML, Courneya KS (2010) Exercise programs for cancer-related fatigue: evidence and clinical guidelines. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 8(8):945–953

Mason C, Alfano CM, Smith AW, Wang CY, Neuhouser ML, Duggan C et al (2013) Long-term physical activity trends in breast cancer survivors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 22(6):1153–1161

Underwood JM, Townsend JS, Stewart SL, Buchannan N, Ekwueme DU, Hawkins NA et al (2012) Surveillance of demographic characteristics and health behaviors among adult cancer survivors—behavioral risk factor surveillance system, United States, 2009. MMWR Surveill Summ 61(1):1–23

Husson O, Mols F, van de Poll-Franse LV (2011) The relation between information provision and health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression among cancer survivors: a systematic review. Ann Oncol 22(4):761–772

Jones LW, Courneya KS, Peddle C, Mackey JR (2005) Oncologists’ opinions towards recommending exercise to patients with cancer: a Canadian national survey. Support Care Cancer 13(11):929–937

Demark-Wahnefried W, Jones LW (2008) Promoting a healthy lifestyle among cancer survivors. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 22(2):319–342

Jones SB, Thomas GA, Hesselsweet SD, Alvarez-Reeves M, Yu H, Irwin ML (2013) Effect of exercise on markers of inflammation in breast cancer survivors: the Yale exercise and survivorship study. Cancer Prev Res (Phila Pa) 6(2):109–118

Rutten LJ, Arora NK, Bakos AD, Aziz N, Rowland J (2005) Information needs and sources of information among cancer patients: a systematic review of research (1980-2003). Patient Educ Couns 57(3):250–261

Jones LW, Courneya KS, Fairey AS, Mackey JR (2004) Effects of an oncologist’s recommendation to exercise on self-reported exercise behavior in newly diagnosed breast cancer survivors: a single-blind, randomized controlled trial. Ann Behav Med 28(2):105–113

Jones L, Courneya K, Peddle C, Mackey J (2005) Oncologists’ opinions towards recommending exercise to patients with cancer: a Canadian national survey. Support Care Cancer 13(11):929–937

Park J-H, Lee J, Oh M, Park H, Chae J, Kim D-I et al (2015) The effect of oncologists’ exercise recommendations on the level of exercise and quality of life in survivors of breast and colorectal cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer 121(16):2740–2748

Buffart LM, Galvao DA, Brug J, Chinapaw MJ, Newton RU (2014) Evidence-based physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors: current guidelines, knowledge gaps and future research directions. Cancer Treat Rev 40(2):327–340

Elme A, Utriainen M, Kellokumpu-Lehtinen P, Palva T, Luoto R, Nikander R et al (2013) Obesity and physical inactivity are related to impaired physical health of breast cancer survivors. Anticancer Res 33(4):1595–1602

Jones LW, Alfano CM (2013) Exercise-oncology research: past, present, and future. Acta Oncol 52(2):195–215

Knols R, Aaronson NK, Uebelhart D, Fransen J, Aufdemkampe G (2005) Physical exercise in cancer patients during and after medical treatment: a systematic review of randomized and controlled clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 23(16):3830–3842

Knobf MT, Winters-Stone K (2013) Exercise and cancer. Annu Rev Nurs Res 31:327–365

Speck RM, Courneya KS, Masse LC, Duval S, Schmitz KH (2010) An update of controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv 4(2):87–100

Schmitz KH, Courneya KS, Matthews C, Demark-Wahnefried W, Galvao DA, Pinto BM et al (2010) American college of sports medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc 42(7):1409–1426

Brown JK, Byers T, Doyle C, Coumeya KS, Demark-Wahnefried W, Kushi LH et al (2003) Nutrition and physical activity during and after cancer treatment: an American Cancer Society guide for informed choices. CA Cancer J Clin 53(5):268–291

American Cancer Society. Nutrition and physical activity during and after cancer treatment: answers to common questions. 2012. (http://www.cancer.org/treatment/survivorshipduringandaftertreatment/nutritionforpeoplewithcancer/nutrition-and-physical-activity-during-and-after-cancer-treatment-answers-to-common-questions) Accessed June 1, 2012

American College of Sports Medicine. Exercising with cancer. (Accessed June 1, 2012, at http://exerciseismedicine.org/assets/page_documents/EIMRxseries_ExercisingwithCancer_2.pdf)

McNair DM, Lorr, M., Droppleman, L.F. Revised manual for the Profile of Mood States. San Diego, CA: educational and industrial testing services.; 1992

Meek PM, Nail LM, Barsevick A, Schwartz AL, Stephen S, Whitmer K et al (2000) Psychometric testing of fatigue instruments for use with cancer patients. Nurs Res 49(4):181–190

Edelman S, Bell DR, Kidman AD (1999) A group cognitive behaviour therapy programme with metastatic breast cancer patients. Psychooncology 8(4):295–305

Hellsten LA, Nigg C, Norman G, Burbank P, Braun L, Breger R et al (2008) Accumulation of behavioral validation evidence for physical activity stage of change. Health Psychol 27(1 Suppl):S43–S53. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.27.1(Suppl.).S43

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC (1982) Transtheoretical therapy: toward a more integrative model of change. Psychol Psychother 19(3):276–288

Bennett JA, Lyons KS, Winters-Stone K, Nail LM, Scherer J (2007) Motivational interviewing to increase physical activity in long-term cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Nurs Res 56(1):18–27

Bandura A (1977) Self-efficacy: toward the unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev 84(2):191–215

Marcus BH, Selby VC, Niaura RS, Rossi JS (1992) Self-efficacy and the stages of exercise behavior change. Res Q Exerc Sport 63(1):60–66

McAuley E (1993) Self-efficacy and the maintenance of exercise participation in older adults. J Behav Med 16(1):103–113

Johnson-Kozlow M, Sallis JF, Gilpin EA, Rock CL, Pierce JP (2006) Comparative validation of the IPAQ and the 7-Day PAR among women diagnosed with breast cancer. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 3:7

Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE et al (2003) International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 35(8):1381–1395

Hintze J. PASS 6.0 Power Analysis and Sample Size for Windows. Keysville, Utah: NCSS; 1996

Hefferon K, Murphy H, McLeod J, Mutrie N, Campbell A (2013) Understanding barriers to exercise implementation 5-year post-breast cancer diagnosis: a large-scale qualitative study. Health Educ Res 28(5):843–856

Olson EA, Mullen SP, Rogers LQ, Courneya KS, Verhulst S, McAuley E (2014) Meeting physical activity guidelines in rural breast cancer survivors. Am J Health Behav 38(6):890–899

Nordin Å, Taft C, Lundgren-Nilsson Å, Dencker A (2016) Minimal important differences for fatigue patient reported outcome measures—a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol 16:62

Schwartz AL, Nail LM, Chen S, Meek P, Barsevick AM, King ME et al (2000) Fatigue patterns observed in patients receiving chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Cancer Investig 18(1):11–19

Lee PH, MacFarlane DJ, Lam TH, Stewart SM (2011) Validity of the international physical activity questionnaire short form (IPAQ-SF): a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 8:115

Jones JM, Olson K, Catton P, Catton CN, Fleshner NE, Krzyzanowska MK et al (2016) Cancer-related fatigue and associated disability in post-treatment cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv 10(1):51–61

Galiano-Castillo N, Ariza-García A, Cantarero-Villanueva I, Fernández-Lao C, Díaz-Rodríguez L, Arroyo-Morales M Depressed mood in breast cancer survivors: associations with physical activity, cancer-related fatigue, quality of life, and fitness level. Eur J Oncol Nursing 18(2):206–210

Sabatino SA, Coates RJ, Uhler RJ, Pollack LA, Alley LG, Zauderer LJ (2007) Provider counseling about health behaviors among cancer survivors in the United States. J Clin Oncol 25(15):2100–2106

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contributions of Jessica Scott, MD, Rachel Wood, MD, Britta Torgrimson, PhD, Jessica Sitemba, and Ms. Laurie Iverson McMahon to the conduct of the study.

Funding

This project was supported by the OHSU Knight Cancer Institute (P30 CA069533) to Dr. Winters-Stone and in part by an Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality-funded PCOR K12 award (K12 HS019456 01) to Dr. Moe. Dr. Winters-Stone is funded by NIH Grants 1R01CA163474, 1R21HL115251, and P30CA069533.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the OHSU Institutional Review Board.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. All patients provided verbal consent prior to participating in study activities.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Winters-Stone, K.M., Moe, E.L., Perry, C.K. et al. Enhancing an oncologist’s recommendation to exercise to manage fatigue levels in breast cancer patients: a randomized controlled trial. Support Care Cancer 26, 905–912 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3909-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3909-z