Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this qualitative study was to gain a rich understanding of the impact that haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) has on long-term survivor’s quality of life (QoL).

Method

Participants included 441 survivors who had undergone HSCT for a malignant or non-malignant disease. Data were obtained by a questionnaire positing a single open-ended question asking respondents to list the three issues of greatest importance to their QoL in survivorship. Responses were analysed and organised into QoL themes and subthemes.

Results

Major themes identified included the following: the failing body and diminished physical effectiveness, the changed mind, the loss of social connectedness, the loss of the functional self and the patient for life. Each of these themes manifests different ways in which HSCT survivor’s world and opportunities had diminished compared to the unhindered and expansive life that they enjoyed prior to the onset of disease and subsequent HSCT.

Conclusions

HSCT has a profound and pervasive impact on the life of survivors—reducing their horizons and shrinking various parts of their worlds. While HSCT survivors can describe the ways in which their life has changed, many of their fears, anxieties, regrets and concerns are existential in nature and are ill-defined—making it exceeding unlikely that they would be adequately captured by standard psychometric measures of QoL post HSCT.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is a demanding therapeutic intervention used in the treatment of a range of life-threatening malignant and non-malignant diseases, with high treatment-related mortality. For those who survive, their lives are often complicated by a wide range of debilitating physical sequelae, with over 90 % of HSCT survivors experiencing at least one serious late adverse effect of treatment [1]. The coexistence of multiple late sequelae, particularly chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD), is widely recognised as having a profound impact upon HSCT survivor’s quality of life (QoL). Therefore, obtaining QoL information is a crucial part of the assessment of treatment success, as improved overall survival is no longer the only factor relevant to the evaluation of a successful medical outcome.

Recent reviews of QoL post HSCT have concluded that many aspects of the individual’s physical, functional, social and psychological QoL improve despite high symptom burden [2–5]. Typical concerns of HSCT survivors include compromised fertility and sexual functioning, fatigue, cognitive declines and physical and emotional distress [2–4, 6, 7]. Fear of recurrence, the challenge of managing uncertainty and frustration at loss of control are also commonly cited psychological sequelae of post-HSCT survivorship [8, 9]. Inevitably, each of these challenges can compromise the survivor’s social roles and identity and may have significant implications for their social interactions and relationships [10–13].

Previous research has highlighted the deleterious impact that late-onset and persistent adverse effects of HSCT may have on survivor’s daily functioning and the intense frustration that survivors may feel as a consequence of these limitations and the intractable unpredictability of recovery [14]. Despite the challenges that HSCT survivorship brings, many survivors, however, are still able to reflect on the positive, transformative nature of HSCT and experience a renewed appreciation for life, a renegotiation of priorities, an enhanced spirituality, liberation from hospitals and the possibility of returning to study/work [15, 16]. While the experience of illness, survival and limitation may encourage many patients to reflect on their own lives and on the human condition, it remains the case that many survivors, particularly those dealing with the effects of chronic GVHD, struggle with the limitations on their lives and functioning as a consequence of the adverse sequelae of HSCT [17, 18]. Indeed, a review of the literature reveals how patients report being surprised by the severity and duration of distressing side effects particularly as it impacts on their ability to return to activities of daily living such as driving and returning to education or employment [14, 19].

While the concept of a ‘shrinking life world’ has been used to describe the patient’s experience in a range of chronic illnesses, including the way in which illness may disrupt or diminish employment, restrict or limit social interactions and erode an individual’s self-concept [20], this concept has yet to be explored in the context of HSCT survivorship. In part, this may be a consequence of what is known about long-term survival post HSCT, as the vast majority of studies reporting on the QoL of HSCT survivors are quantitative studies, and often retrospective registry reviews, and rely upon a limited range of measures to assess QoL. While such studies provide important and useful information about QoL, at the same time, they often fail to fully capture the ways in which survivor’s lives have changed, including the existential and often ill-defined regrets, concerns, fears and anxieties that they experience. Although a number of important qualitative studies have provided some insights into the everyday challenges of survivorship [6, 14, 21, 22], there is also no doubt that more qualitative exploration of HSCT survivorship needs to be done in order to guide the development of models of care to improve symptom management, identify survivors at increased risk of poor QoL, provide opportunities for early intervention and help both health professionals and survivors with medical decision-making. This study describes the qualitative insights gained by asking a population of long-term survivors of HSCT a single open-ended question about the quality of their life post HSCT.

Methods

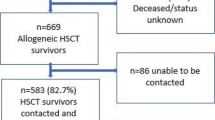

The study sample was selected from allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation databases of the four major adult metropolitan hospitals in New South Wales, Australia, that perform HSCT. Participants were eligible if they were ≥18 years of age and had undergone an allogeneic BMT between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2012 and could read and write English. Consenting participants were given the option to self-complete the questionnaire or to complete a telephone interview with one of the researchers. A second round of telephone calls was made to consenting participants who had not returned the survey within a month. A total of 1475 allogeneic HSCT were performed in the study period. Of the 669 recipients known to be alive at study sampling, 583 were contactable and were sent study packs and 441 returned the completed survey. No respondent opted for a telephone interview. Three percent declined participation. Demographic characteristics of the study respondents are depicted in Table 1. The study was approved by the Northern Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee (NSLHD Reference: 1207-217M).

In order to capture the diversity of responses and to avoid a positive or negative bias, data was obtained by positing a single open-ended question asking respondents to list the three issues of greatest importance to their QoL post HSCT. Responses to the QoL question were copied verbatim, maintaining confidentiality, into a word document. The analytical framework used for initial coding was guided by the model of QoL conceived by Ferrell et al. [23]. We further refined the thematic scheme through multiple readings and line-by-line coding. Initially 232 codes were identified. The codes were then grouped together with codes of similar meaning. The consolidated codes were further condensed to five common themes: the failing body and diminishing physical effectiveness, the changed mind, the loss of social connectedness, the loss of the functional self and the patient for life. The first and last authors performed the analysis, but final agreement on the themes was only reached after three other authors had independently read and provided commentary on both the codes and the characteristics of each category. Qualitative analysis was performed on NVivo software.

Results

While some survivors experienced relatively good QoL post HSCT, many struggled with pervasive and unrelenting side effects. The overwhelming theme evident in the responses of those struggling with QoL was that their world and opportunities had become profoundly diminished compared to the life they enjoyed prior to disease and HSCT. (A selection of participant quotes exemplifying the themes are detailed in Table 2.)

The failing body and diminishing physical effectiveness

The majority of respondents reported that the toxicity and immunosuppression associated with HSCT resulted in a plethora of long-term impairments of survivor’s physical, emotional and psychosocial function. A considerable number of survivors reflected on the impact of cGVHD. Reference to GVHD was frequently linked to comments highlighting the unrelenting implications for the individual’s physical, social and psychological functioning. A large number of survivors reflected on the physical burden of transplant which was often associated with reduced emotional and social functioning including, inter alia, fatigue, employment, depression and declines in socialisation. Some respondents reflected that their social world had shrunk as a consequence of their physical restrictions and incapacity to regain fitness. Many reflected that the complications of transplant transformed their personal world and their intimate relationships, particularly their sexual identity, sexual functioning and fertility. A large number of women reported early onset of menopause, decreased sexual enjoyment, reduced fertility, vaginal dryness, irritation, pain and bleeding, while some men reported erectile dysfunction, lowered libido and decreased sexual enjoyment. Infertility and reports of sexual dysfunction were often linked to the survivor’s low mood, poor self-esteem and relationship difficulties. The impact of HSCT on fertility, sexuality, identity and physical function led some respondents to reflect on the difficulty they faced in trying to secure future relationships. Despite many respondents reflecting on the persistence of significant medical complications and the functional limitations that compromised their QoL, the vast majority of respondents reported feeling a deep appreciation for life post HSCT.

The changed mind

Many survivors noted a range of mood changes post transplant including anger, frustration, anxiety and depression. Some survivors linked mood disturbances to social isolation. Several HSCT survivors also described cognitive changes following HSCT, including memory deficits, decreased concentration and attention, mental fatigue and reduced reaction times. Some survivors linked these cognitive impairments to problems with employment and relationships. One of the most dominant emotions expressed by many respondents was fear—the fear of disease recurrence, the fear of chronic GVHD and the fear of secondary malignancies occurring post HSCT. According to several subjects, this created enormous distress. For some subjects, this deep and pervasive fear made them reluctant to take risks or plan for the future, which further perpetuated shrinking opportunities in their life.

The loss of social connectedness

Perhaps unsurprisingly, family and friends featured prominently in respondents’ descriptions of their QoL post HSCT, with many emphasising the importance of both the physical and emotional support they received from significant others throughout both treatment and survivorship. At the same time, however, many subjects described the terrible impact that HSCT had had on their loved ones and the guilt that they felt about the way HSCT had changed not only their own lives but also the lives of those close to them. Some respondents also noted the degree to which they were dependent—physically, emotionally, socially and financially—upon others and the way that this made them feel.

The loss of the functional self

Many respondents reported an association between undergoing transplant and the loss of some of the certainties that most people take for granted—like health, stable relationships, sustained employment and financial security. For some, the loss of employment and the loss of capacity to work were linked to their sense of self-worth. Indeed for many subjects, work, while previously a central part of their lives, had become stressful and exhausting. Many survivors reported missing numerous workdays due to ill health, and some reported a loss of career momentum including the necessity to change their job or downsize to part-time job. Numerous subjects also reported that they were unable to return to work at all, with many describing how these changes caused them further distress including anxiety, depression and impairments in social functioning. A few survivors also reflected on the financial burden of HSCT including the loss of income. References to the financial burden of transplant were often linked to comments regarding the patient’s sense of self-worth and financial security.

The patient for life—the unrelenting nature of follow-up

Many survivors described the burdensome requirement of life-long follow-up to prevent, identify and treat the myriad of late effects that complicate transplant survival. Some reported on the redirection of their attention from broader life issues to an intense focus on health and well-being. Some reflected on the restrictions in their life perpetuated by the unrelenting nature of follow-up including loss of productive function, social isolation and a diminished self-concept. Importantly, while many reflected on the fact that long-term follow-up (LTFU) was onerous, some respondents recognised how necessary it was and described how much they relied upon access to multidisciplinary long-term care and the expertise available through their transplant centre. Some survivors stated their desire to live within a safe distance from their transplant centre. This specification was often linked to the individual’s anxiety about the uncertainties and dangers posed by the future.

A few survivors felt that the special expertise, knowledge and care provided by their haematologist and HSCT team were simply not available elsewhere. In many cases, this sense was heightened by adverse experiences that HSCT survivors had experienced before transplant and subsequent to it. This was particularly true for patients living in rural, regional or remote areas. Concerns regarding lack of expertise and knowledge were not, however, specific to those living in rural areas, with a few survivors expressing concerns regarding the lack of knowledge of their general practitioners. Importantly, however, even though some expressed concerns about their local doctor, others were very grateful for their relationship with them.

Conclusions

As survival following HSCT has improved, attention has increasingly turned to the impact of HSCT upon recipients’ QoL and their experience of survivorship. Although a number of quantitative studies suggest that those who survive at least 1–2 years following HSCT have an acceptable QoL [2–5], it is clear that long-term survivors of HSCT face ongoing challenges and experience limitations in many domains of their life. By asking survivors one simple question—to describe the three complications of HSCT that have had the most impact upon their QoL—we were rewarded with a rich picture of the challenges of survivorship. What was clear from the accounts provided by HSCT survivors in this study was that QoL was most impacted by the physical burden of the failing body, the cognitive and mood changes, the diminished social connectedness, the loss of functionality and the burden of being a patient for life. These QoL challenges were shown to shrink various aspects of the HSCT survivor’s world—restricting not only their capacities and function but also their identity and relationships. While existing literature has described the changes in self-concept and the loss of identity associated with reductions in HSCT survivor’s ability to perform everyday functions of living, this is the first study to conceptualise these losses in terms of a shrinking life world [24, 25].

Many respondents to our study reported feeling a sense of dislocation and isolation in the years following their transplant—a sense heightened and perpetuated by their real or perceived fear of infection and GVHD. The functional impairments suffered as a result of overwhelming fatigue were also ubiquitous. Prior research has identified that GVHD and fatigue often compromise survivor’s QoL for many years post transplant and are a frequent cause of mood disturbance [3, 4, 24]. For some survivors, this physical and psychological debility was so severe that they felt they had lost their sense of identity, independence and self-worth and were unable to fulfil the social, familial and professional roles that marked out ‘who they were’ before their HSCT. For others, fears about their capacity to cope intensified their degree of dependence—binding them to their transplant centre and to the healthcare professionals that they trusted and preventing them from seeing a world beyond the geographical and emotional ‘gaze’ of their medical care. Not surprisingly, many survivors were distressed by their loss of function, particularly as it compromised those things that provide certainty and stability, like sustained employment and financial security. This is an important finding and is consistent with other recent studies that have highlighted the ongoing challenges associated with job insecurity, discrimination, career derailment and delayed goals, financial loss and instability and constraints on job mobility [19].

According to the literature, family and friends play an important function in providing social support. However, patients also worry that they may become a burden to others. One study concluded that some survivors felt their inability to contribute to the family and their lack of productivity made them feel useless [11]. These findings were consisted with the results of this study which highlighted both the importance of family to survivors and the guilt they experienced as a result of their physical, emotional, social and financial dependence. While prior to HSCT many haematologists and allied health professionals encourage survivors to consider the possibility that they may become ‘a patient for life’, in reality, it is difficult, if not impossible, to convey what this actually means, what impact transplantation may have on every aspect of a survivor’s life, how unrelenting follow-up may feel and how difficult it may be for survivors to adapt to their post-HSCT challenges. Previous studies have concluded that while many survivors report adequate QoL, many do not believe they have returned to normal [25]. However, this is not to say that survivors of HSCT (particularly those that modify their expectations and accept that their lives are different post HSCT than they were beforehand) do not adapt, do not resume normal activities, do not cope with the uncertainty implicit in survival post HSCT or do not accommodate the need to cease or downsize their employment or modify their relationships and social roles [23]. Rather, it is to acknowledge that some survivors of HSCT will be more profoundly impacted upon than others by their failing body, impaired cognition, emotional distress and social isolation [3, 4].

Previous research has highlighted the important role that pre- and post-transplant education may play in improving the QoL of HSCT survivors and in enabling them to learn strategies to assist them cope with the changes in their lives [14]. As a result, it is now generally recognised that transplant centres should endeavour to incorporate education, counselling and support into every stage of the transplant recipient’s journey [14]. But information in any form is very different to personal experience. It is one thing for a patient who is shortly to undergo a HSCT to be told by the transplant team that they have a 60 % chance of developing chronic GVHD but a very different thing to experience it. And it is one thing to record the frequency or numerical grade or extent of HSCT complications but another thing again to describe in one’s own words what it is to experience them. While it is important to collective quantitative measures of QoL, it is also crucial to recognise the limitations of this form of data and supplement it with qualitative data that may reveal the full extent and meaning of the challenges to HSCT survivors’ QoL.

The results of this study are important not simply because they contribute to the growing qualitative literature on post-HSCT survivorship but because it suggests that a single question may provide important insights into the experience of survival post HSCT. And this is important, because, unlike hour-long in-depth interviews, time could be found in the routine follow-up of HSCT survivors to ask them a question about how they are coping and what is of most concern to them. This study has some very clear limitations that caution against over-generalising the results to all HSCT survivors. Our analysis was based upon written responses to a single question about QoL, and we did not use other qualitative methods, such as in-depth interviews or ethnographic methods that would have undoubtedly provide a more nuanced account of the experience of survival post HSCT. But while other qualitative methodologies may have provided more detailed accounts of the experience of survivorship, the use of a single question prompt in this study to elicit qualitative descriptions of post-HSCT survivorship suggests other benefits. Firstly, our results suggest that asking a single, very specific question of HSCT survivors about their QoL may enrich and triangulate the quantitative description of survivorship provided by other psychometric measures of QoL commonly used in post-HSCT follow-up. And secondly, our results provide the possibility of translation, as unlike complex surveys or in-depth, unstructured interviews, regularly asking a patient to describe the main things that are having an adverse impact upon their QoL may be easily done, have clinical utility and have limited resource costs.

It is clear from the accounts provided by the respondents to this survey that while HSCT provides enormous benefits, it also is enormously challenging and may have a range of complex impacts upon the QoL of HSCT recipients and upon their experience of survivorship. While many will cope, and adapt, and continue to cherish the life they have, the vast majority will face challenges along the way. While better education of HSCT recipients may help the work that survivors need to do post HSCT, it is unlikely that it will ever be able to completely prepare HSCT recipients for what lies ahead. In these circumstances, what may be most important is for HSCT services to acknowledge and understand the pervasive impact of HSCT and offer reassurance that no matter what occurs, whether expected or unanticipated, they will always be available to provide care and support.

References

Cant AJ, Galloway A, Jackson G (eds) (2007) Practical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blackwell, Malden, pp 1–13

Hjermstad MJ, Kaasa S (1995) Quality of life in adult cancer patients treated with bone marrow transplantation—a review of the literature. Eur J Cancer 31A:163–173

Mosher C, Redd W, Rini C, Burkhalter J, DuHamel K (2009) Physical, psychological, and social sequelae following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a review of the literature. Psychooncology 18:113–127

Pidala J, Anasetti C, Jim H (2009) Quality of life after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood 114:7–19

Andrykowski MA (1994) Psychosocial factors in bone marrow transplantation: a review and recommendations for research. Bone Marrow Transplant 13:357–375

Haberman M, Bush N, Young K, Sullivan KM (1993) Quality of life of adult long-term survivors of bone marrow transplantation: a qualitative analysis of narrative data. Oncol Nurs Forum 20:1545–1553

Le RQ, Bevans M, Savani BN et al (2010) Favorable outcomes in patients surviving 5 or more years after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for hematologic malignancies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 16(8):1162–1170

Baker F, Zabora JG, Polland A, Burns J, Wingard JR (1999) Reintegration after bone marrow transplantation. Cancer Pract 7:190–197

Rueda-Lara M, Lopez-Patton MR (2014) Psychiatric and psychosocial challenges in patients undergoing haematopoietic stem cell transplants. Int Rev Psychiatry 26:74–86

Kopp M, Holzner B, Meraner V, Sperner-Unterweger B, Kemmler G, Nguyen- Van-Tam DP, Nachbaur D (2005) Quality of life in adult hematopoietic cell transplant patients at least 5 yr after treatment: a comparison with healthy controls. Eur J Haematol 74(4):304–308

Liang TL, Lin KP, Yeh SP, Lin HR (2014) Lived experience of patients undergoing allogeneic peripheral hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Int J Res MH 4(2):2307–2083

Rueda-Lara M, Lopez-Patton MR (2014) Psychiatric and psychosocial challenges in patients undergoing haematopoietic stem cell transplants. Int Rev Psychiatry 26(1):74–86

Adelstein KE et al (2014) Importance of meaning-making for patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Oncol Nurs Forum 41(2):E172–E184

Jim HS, Quinn GP, Gwede CK, Cases MG, Barata A, Cessna J et al (2014) Patient education in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant: what patients wish they had known about quality of life. Bone Marrow Transplant 49:299–303

Wettergren L, Sprangers M, Bjorkholm M, Langius-Eklof A (2008) Quality of life before and one year following stem cell transplantation using an individualized and a standardized instrument. Psychooncology 17:338–346

Andrykowski MA, Brady MJ, Hunt JW (1993) Positive psychosocial adjustment in potential bone marrow transplant recipients: cancer as a psychosocial transition. Psycho-Oncology 2:261–276

Molassiotis A, Boughton BJ, Burgoyne T, van den Akker OB (1995) Comparison of the overall quality of life in 50 long-term survivors of autologous and allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. J Adv Nurs 22(3):509–516

Pidala J, Kurland B, Chai X, Majhail N, Weisdorf DJ, Pavletic S et al (2011) Patient-reported quality of life is associated with severity of chronic graft-versus-host disease as measured by NIH criteria: report on baseline data from the Chronic GVHD Consortium. Blood 117(17):4651–4657

Stepanikova I, Powroznik K, Cook KS, Tierney DK, Laport GG (2016) Exploring long-term cancer survivors’ experiences in the career and financial domains: interviews with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation recipients. J Psychosoc Oncol 34(1–2):2–27

Gullick J, Stainton MC (2008) Living with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: developing conscious body management in a shrinking life-world. J Adv Nurs 64:605–614

Beeken RJ, Eiser C, Dalley C (2011) Health-related quality of life in haematopoietic stem cell transplant survivors: a qualitative study on the role of psychosocial variables and response shifts. Qual Life Res 20:153–160

Barata B, Wood W, Choi SW, Jim HS (2016) Unmet needs for psychosocial care in hematologic malignancies and hematopoietic cell transplant. Curr Hematol Malig Rep 11:280–287

Ferrell B, Grant M, Schmidt GM, Rhiner M, Whitehead C, Fonbuena P, Forman SJ (1992) The meaning of quality of life for bone marrow transplant survivors. Part I: the impact of bone marrow transplant on quality of life. Cancer Nurs 15(3):153–160

Jim HS, Sutton SK, Jacobsen PB, Martin PJ, Flowers ME, Lee SJ (2016) Risk factors for depression and fatigue among survivors of hematopoietic cell transplantation. Cancer 122:1290–1297

Polomeni A, Lapusan S (2012) Understanding HSCT patients psychosocial concerns. EBMT News. 1–5

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the HSCT survivors who participated in this research and the sponsorship and support provided by the New South Wales Agency for Clinical Innovation/NSW Blood and Marrow Transplant Network and the Northern Blood Research Centre.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brice, L., Gilroy, N., Dyer, G. et al. Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation survivorship and quality of life: is it a small world after all?. Support Care Cancer 25, 421–427 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3418-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3418-5