Abstract

Context

Conversations about end-of-life (EOL) wishes are challenging for many clinicians. The Go Wish card game (GWG) was developed to facilitate these conversations. Little is known about the type and consistency of EOL wishes using the GWG in advanced cancer patients.

Methods

We conducted a randomized controlled trial to assess the EOL wishes of 100 patients with advanced cancer treated at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. The purpose of this study was to determine the EOL wishes of patients with advanced cancer and to compare patients’ preference between the GWG and List of wishes/statements (LOS) containing the same number of items. Patients were randomized into four groups and completed either the GWG or a checklist of 35 LOS and one opened statement found on the GWG cards; patients were asked to categorize these wishes as very, somewhat, or not important. After 4–24 h, the patients were asked to complete the same or other test. Group A (n = 25) received LOS-LOS, group B (n = 25) received GWG-GWG, group C (n = 26) received GWG-LOS, and group D (n = 24) received LOS-GWG. All patients completed the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) for adults before and after the first test.

Results

Median age (interquartile range = IQR): 56 (27–83) years. Age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, religion, education, and cancer diagnosis did not differ significantly among the four groups. All patients were able to complete the GWG and/or LOS. The ten most common wishes identified as very important by patients in the first and second test were to be at peace with God (74 vs. 71 %); to pray (62 vs. 61 %); and to have family present (57 vs. 61 %). to be free from pain (54 vs. 60 %); not being a burden to my family (48 vs. 49 %); to trust my doctor (44 vs. 45 %); to keep my sense of humor (41 vs. 45 %); to say goodbye to important people in my life (41 vs. 37 %); to have my family prepared for my death (40 vs. 49 %); and to be able to help others (36 vs. 31 %). There was significant association among the frequency of responses of the study groups. Of the 50 patients exposed to both tests, 43 (86 %) agreed that the GWG instructions were clear, 45 (90 %) agreed that the GWG was easy to understand, 31 (62 %) preferred the GWG, 39 (78 %) agreed that the GWG did not increase their anxiety and 31 (62 %) agreed that having conversations about EOL priorities was beneficial. The median STAI score after GWG was 48 (interquartile range, 39–59) vs. 47 (interquartile range, 27–63) after LOS (p = 0.2952).

Conclusion

Patients with advanced cancer assigned high importance to spirituality and the presence/relationships of family, and these wishes were consistent over the two tests. The GWG did not worsen anxiety.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

End-of-life (EOL) conversations can be difficult for patients, families[1–3] and other caregivers, physicians, and nurses[4–9] but can provide an opportunity for patients and their caregivers to express their wishes about care.[10, 11] Patient-centered communication is a key approach to navigating these emotional conversations.[1–3] To maximize the best possible quality of life for patients with advanced cancer and other terminal illnesses, healthcare personnel must have a sensitive and culturally competent communication style with patients and their caregivers to promote a healing environment.

Several studies have proposed different ways to communicate with patients and families about EOL issues.[12, 13] Important skills include eliciting patients’ and families’ perspectives in an open-ended fashion, listening intently, and responding to emotions with empathy.[1–3] For example, Stewart et al. described four evidence-based dimensions of good patient-doctor communication: providing clear information; empowering patients to take an active role in decision-making; demonstrating empathy, support, and positive affect; and establishing mutual goals [14].

Knowing and honoring EOL wishes could improve the patient’s sense of control,[15, 16] affirm the patient as a whole person, provide adequate symptom control, facilitate decision-making, prepare the patient for death, and ultimately provide the patient with a good death.[16, 17] In the past decade, research has emphasized the importance of eliciting patients’ values and goals rather than patients’ preferences for a particular life-sustaining treatment.[18, 19] A survey of a national, cross-sectional, stratified random sample of 340 seriously ill patients found that the most important attributes of EOL quality included freedom from pain, peace with God, the presence of family, mental awareness, and the honoring of treatment choices.[17] These values are consistent with findings from other studies that have shown that although pain management is often patients’ highest priority, spiritual, financial, and interpersonal issues are also important.[19–21] Limited research has explored important EOL wishes of patients with advanced cancer, and few tools have been validated for this population.

One tool that is available is the Go Wish card game (GWG), which was developed by the Coda Alliance. Coda was funded in 2005–2006 by Archstone Foundation to develop and test a program to educate assisted-living residents, their family members, and assisted-living facility staff about EOL care options and advance care planning. The GWG was developed to stimulate discussion that would focus on values and wishes about EOL care. It was found to be effective for elderly people with mild limited cognition, as well as for people with limited literacy and limited skills in the English language without seeming too simplistic for those with higher education [22].

The final design of the 36 cards incorporates lessons learned during the assisted-living facility trials, as well as from other tryouts of the cards with community groups and in training conferences with health care professionals. With the advice of a communication consultant, the wording on the cards was revised to be consistent in tone, predominantly stated in a positive voice, and simplified in reading level. The text was put onto a large, easy-to-read layout.[22] Currently, the GWG is a set of 36 cards designed to allow patients to identify and prioritize their EOL wishes. This tool is beneficial for promoting EOL conversations among patients, their loved ones, and their medical care providers [22].

Different methodological issues have been documented in the evaluation of patient problems and concerns during the terminal stage of life.[23] The GWG provides a wide selection of examples of EOL concerns with which the patient can agree, disagree, or amend and interpret.[22–24] In an observational study, Lankarani-Fard et al. evaluated the feasibility of using the GWG with seriously ill inpatients to determine their EOL priorities. Of the 133 patients, 33 (25 %) completed the game and prioritized freedom from pain, peace with God, and prayer [19]. However, limited literature describes the feasibility of the GWG in patients with advanced cancer. The purpose of this study was to determine the EOL wishes of patients with advanced cancer and to compare patients’ preference between the GWG and list of wishes/statements (LOS) containing the same number of items.

Patients and methods

Our randomized controlled trial was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Patient population

Patients with advanced cancer who were aged 18 years or older, who were cognitively intact, and who were seen in the Inpatient Acute Palliative Care Unit were included in this study. Advanced cancer was defined as locally advanced or metastatic disease that was considered incurable. Patients were excluded if they had delirium (Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale score ≥ 7)[25–27] or could not complete the GWG independently because of severe emotional and/or physical symptom distress or because of physical limitations (visual or motor impairment) as determined by the clinician in charge of the patient. From the medical record, baseline information was collected on age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, religion, education, and cancer diagnosis.

Randomization

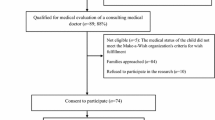

Patients were randomized into four groups; each group of patients was asked to complete either the GWG or LOS, and 4–24 h later, the patients were asked to complete the same or the other instrument. Group A (n = 25) received LOS and LOS, group B (n = 25) received GWG and GWG, group C (n = 26) received GWG and LOS, and group D (n = 24) received LOS and GWG. A minimum of about 4 h between tests was required to ensure that the patients might not remember their previous answers and their clinical environment remains stable. Figure 1 shows the study design.

Tools

GWG

The GWG is designed to stimulate conversations about EOL care/issues and allow patients to prioritize their wishes. Each of the 36 GWG cards includes a short statement describing an important EOL issue. These statements are based on the results of a study that investigated important issues for patients to consider in the last few months of their lives [22]. The GWG is designed to be easy to use with minimal instructions.

The patients were instructed by our trained research coordinator to divide the cards into three groups: ten very important issues, ten somewhat important issues, and 16 not important issues. For our analysis, we used 35 cards (we excluded one card, the open-ended statement card because none of the participants used it). The patients completed the task by themselves in the presence of our trained research coordinator. The patients did not have EOL discussions prior to completing the tasks.

List of wishes/statements

To validate the GWG for patients with advanced cancer, we developed a list of wishes/statements (LOS), a checklist with the same 35 statements and one blank space used on the GWG cards. Patients were asked to check the ten statements that were very important in the first column and the ten statements that were somewhat important in the second column and to leave unchecked the 16 statements that were not important.

Tool preference questionnaire

To explore patients’ preferences between the GWG and LOS, we created a questionnaire with questions about patients’ experience with card games (question 1) and the GWG (question 2), understanding of the tools (questions 3 and 4), and preference between the cards and the checklist (question 5). We also asked whether the GWG increased patients’ anxiety (question 6) and whether patients considered EOL conversations beneficial (question 7). This questionnaire was provided to the patients after the second test completed (GWG or LOS).

To determine the consistency of patients’ EOL priorities, we analyzed the responses from the first and second tests for groups A and B. The agreement percentage for each patient was calculated as the number of items selected as very important on both tests divided by 10.

State-trait anxiety inventory

The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) for adults is commonly used to assess anxiety.[28] The S-Anxiety scale consists of 20 statements that evaluate how respondents feel at that moment (e.g., “I am tense,” “I am worried,” “I feel calm,” or “I feel secure”). All items are rated on a 4-point scale (from “not at all” to “very much”). Higher scores indicate greater anxiety. STAI was given to the patients before and after completing the first EOL test to evaluate anxiety levels.

Statistical analysis

GWG was determined feasible if at least 50 % of the patients completed it following all of the rules of GWG. One hundred patients allowed us to construct a 95 % confidence interval around the proportion of patients who completed the test of 90 % ± 5.9 % (assuming an observed proportion of 90 %; NQuery 7.0). Using a two-sided binominal exact test, 100 patients provide 80 % power at a type I error rate of 5 % to test the hypothesis of 64 % correct completion versus a null hypothesis of 50 % or less correct completion.

Test-retest consistency compared the agreement percent of the follow-up test and baseline test between the A group and B group. The agreement percent for each patient was defined as the ratio of the number of items selected as “Very Important” for both tests over 10.

Data were summarized using standard descriptive statistics and contingency tables. Correlation of continuous variables was assessed using the Spearman correlation coefficient. Association between categorical variables was determined using the chi-squared test or Fisher exact test. A paired t test was used to assess the differences between the two STAI scores within each patient group. A two-sample t test was used to assess the differences in age and STAI score between groups. Histograms were used to show the distribution of the data. All computations were performed using SAS software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

One hundred patients completed the study. Patients’ characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The groups did not differ significantly in age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, religion, education, or cancer diagnosis. The ten most common “very important” wishes identified by patients during the first and second tests were “to be at peace with God” (74 vs. 71%, r = 0.73, p < 0.0001); “to pray” (62 vs. 61 %, r = 0.57, p < 0.0001); “to have my family with me” (57 vs. 61 %, r = 0.23, p = 0.0280); “to be free from pain” (54 vs. 60 %, r = 0.31, p = 0.0019); “not being a burden to my family” (48 vs. 49 %, r = 0.23, p = 0.0241 ); “to trust my doctor” (44 vs. 45 %, r = 0.49, p < 0.0001); “to keep my sense of humor” (41 vs. 45 %, r = 0.53, p < 0.0001); “to say goodbye to important people in my life” (41 vs. 37 %, r = 0.46, p < 0.0001); “to have my family prepared for my death” (40 vs. 49 %, r = 0.48, p < 0.0001); and “to be able to help others” (36 vs. 31 %, r = 0.52, p < 0.0001). The frequency and correlation of each item identified as very important during the first and second tests are presented in Table 2.

Among the 50 patients in groups C (GWG-LOS) and D (LOS-GWG), only five (10 %) had used the GWG before; 43 (86 %) agreed that the GWG instructions were clear; 45 (90 %) agreed that the GWG was easy to understand; 31 (62 %) preferred the GWG; 39 (78 %) agreed that the GWG did not increase their anxiety; and 31 (62 %) agreed that discussing EOL priorities was beneficial (p = NS for all items). Table 3 summarizes the patients’ evaluation of the GWG.

Test-retest consistency for group A showed a median agreement percent (IQR) of 60 % (40–100 %) vs. 70 % (30–100 %) for group B. The difference of agreement percent between these two groups was not statistically significant (p = 0.68).

The concordances on the wish statements among all groups are showed in Table 4. The wishes with higher and significant correlation were as follows: to be at peace with God, to die at home, not being short of breath, to be free from anxiety, and to have human touch.

We compared the median STAI scores of the GWG group and the LOS group and analyzed the differences in the STAI total score within and between these two groups. The median STAI scores before the first test were 49 (IQR, 25–80) for the GWG group and 46 (IQR, 20–65) for the LOS group (p = 0.0350). The median STAI scores after the first test were 48 (IQR, 39–59) for the GWG group and 47 (IQR, 27–63) for the LOS group (p = 0.2952). The changes in the STAI total score in the GWG group and LOS group were not statistically significant within or between groups.

Discussion

A high proportion of our population expressed their most important wishes as those involving spiritual aspects (“to be at peace with God” and “to pray”). Although several studies have shown that patients with advanced illness assign a high priority to freedom from pain and consider painlessness one component of a good death.[17, 29] our study showed that spiritual issues also have high priority for patients and should be considered aspects of a good death. We previously found that 98 of 100 patients with advanced cancer considered themselves spiritual [30], and True et al. found that 84% of 68 patients with advanced lung cancer considered themselves to be “moderately to very spiritual.”[31] Collectively, these findings suggest the importance of asking patients about their EOL spiritual needs and wishes.[32] Whether patients were exposed to GWG or LOS, the findings were very consistent and it is very reassuring that either of these forms could be used according to the patient’s preferences.

Good communication about EOL issues and the use of tools to explore EOL wishes such as GWG can help prevent distress associated with the dying process. In our study, most of the patients felt comfortable exploring their EOL wishes using the GWG and this did not increased anxiety on them. Abba et al. evaluated an intervention in the general population (n = 498) to encourage participants to plan the end of their life and to communicate their wishes. The study showed that people are comfortable with talking about EOL issues (mean score, 8.28/10).[33] For patients with advanced illness or those near death, an early exploration of EOL needs and wishes is necessary to improve individual care.[34] Healthcare professionals may find it difficult to understand a patient’s needs in the patient’s last week of life when the most complex physical and emotional problems arise.[35, 36] In a national survey, Steinhauser et al. found that eight items, including being mentally aware, being at peace with God, and not being a burden, were rated as very important by patients but were rated as less important by physicians.[20] In this setting, the GWG can help address patients’ priorities and help them identify new wishes and realistic goals.[36, 37] More research is needed to evaluate EOL wishes and realistic goals of care.

Several studies have found differences in the end of life wishes of patients depending on their diagnosis. Booij et al. found that patients with Huntington disease assigned high priority to specific aspects of EOL care, such as fluid and food administration or admission to a hospital or nursing home. In the majority of these cases, the patient or a relative took the initiative to discuss these EOL wishes with the physician.[38] Another study found that nursing home residents wanted to be asked about their EOL preferences.[39] People with dementia and family caregivers strongly emphasized the importance of being comforted through engagement with the senses, through social connection, and through spiritual engagement.[40] The mentioned wishes seems to be across the types of illnesses, since in our study with advanced cancer patients, high-priority wishes included appropriate relationships with a higher power (God) and with others (family and clinicians), appropriate attitudes, and symptom control.

Our findings validate the GWG for patients with advanced cancer. We found an adequate test-retest consistency and a high correlation of several wish statements among all the groups. As in previous studies,[19, 22] our results showed that the GWG was a feasible way to prioritize patients’ EOL wishes and did not increase anxiety in patients.

Interestingly the wishes with higher and significant correlation among our population, especially “to be at peace with God and to pray”, were consistent in all the different groups independently of the order of the tool given (as shown in Table 4). This might suggest the strong connection among our population with a higher power/God, and/or possible the need to be closer to a higher power, and/or a needed spiritual connection at the end of life.

Our study was limited by its single-institution setting. A larger study involving a more diverse population is needed. However, the GWG is a simple tool to start discussions about EOL wishes, is preferred over the LOS, and elicits consistent wishes; these wishes highlighted the importance of connectedness through relationships with a higher power and with family/caregivers. Another important point to consider is that our study was conducted in the South Texas area where a high percentage of individuals consider themselves spiritual and/or religious. [30, 41] Further research is needed to evaluate these findings in different geographic regions. Patients assigned high importance to spirituality and the presence/relationships of family, and these wishes were consistent over the two tests. The GWG was preferred to a LOS and did not worsen anxiety. These findings are important in our daily practice since exploring the EOL wishes of patients and paying attention to their spiritual needs and struggles would benefit quality of life and improve care at the end of life. Patients’ cultural and spiritual beliefs may yield different views about who should make decisions for the individual at the end of life and what constitutes optimal care at the end of life. [42] This provides a personalized inventory of priorities across different cultural and sociodemographic groups. The importance of this influence and the nature of the interaction between cultural aspects, spiritual beliefs, and EOL care preferences remain poorly understood. Multicenter prospective studies, at national and international levels will increase our understanding about EOL wishes of patients of advanced and terminal illnesses in a multicultural setting.

References

Delgado-Guay MO, De la Cruz MG, Epner DE (2013) “I don’t want to burden my family”: handling communication challenges in geriatric oncology. Ann Oncol 23(Supplement 7):vii30–vii35

Epstein RM, Street RL Jr (2007) Patient-centered communication in cancer care: promoting healing and reducing suffering. Bethesda, MD, National Cancer Institute

Beckman HB, Frankel RM (2003) Training practitioners to communicate effectively in cancer care: it is the relationship that counts. Patient Educ Couns 50:85–89

Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Shannon SE, et al. (2001) The family conference as a focus to improve communication about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: opportunities for improvement. Crit Care Med 29(2 Suppl):26–33

DesHarnais S, Carter RE, Hennessy W, et al. (2007) Lack of concordance between physician and patient: reports on end-of-life care discussions. J Palliat Med 10(3):728–740

Doukas DJ, Hardwig J (2003) Using the family covenant in planning end-of-life care: obligations and promises of patients, families, and physicians. J Am Geriatr Soc 51(8):1155–1158

Keating NL, Landrum MB, Rogers SO Jr, et al. (2010) Physician factors associated with discussions about end-of-life care. Cancer 116(4):998–1006

Mack JW, Cronin A, Taback N, et al. (2012) End-of-life care discussions among patients with advanced cancer: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 156(3):204–210

Boyd D, Merkh K, Rutledge DN, et al. (2011) Nurses’ perceptions and experiences with end-of-life communication and care. Oncol Nurs Forum 38(3):E229–E239

Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. (2008) Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA 300(14):1665–1673

Heyland DK, Dodek P, Rocker G, et al. (2006) What matters most in end-of-life care: perceptions of seriously ill patients and their family members. CMAJ 174(5):627–633

LeGrand SB (2000) Communication in advanced disease. Curr Oncol Rep 2(4):358–361

Borreani C, Brunelli C, Bianchi E, et al. (2012) Talking about end-of-life preferences with advanced cancer patients: factors influencing feasibility. J Pain Symptom Manag 43(4):739–746

Stewart M, Brown JB, Boon H, et al. (1999) Evidence on patient-doctor communication. Cancer Prev Control 3(1):25–30

Field MJ, Cassel CK (1997) Approaching death: improving care at the end of life. National Academy Press, Washington, DC

Kehl KA (2006) Moving toward peace: an analysis of the concept of a good death. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 23(4):277–286

Steinhauser KE, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, et al. (2000) In search of a good death: observations of patients, families, and providers. Ann Intern Med 132:825–832

Lorenz KA, Lynn J, Dy SM, et al. (2008) Evidence for improving palliative care at the end-of-life: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 148:147–159

Lankarani-Fard A, Knapp H, Lorenz KA, et al. (2010) Feasibility of discussing end-of-life care goals with inpatients using a structured, conversational approach: the go wish card game. J Pain Symptom Manag 39(4):637–643

Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, et al. (2000) Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. J Am Med Assoc 284(19):2476–2482

Quill T, Norton S, Shah M, et al. (2006) What is most important for you to achieve? An analysis of patient responses when receiving palliative care consultation. J Palliat Med 9:382–388

Menkin ES (2007) Go wish: a tool for end-of-life care conversations. J Palliat Med 10(2):297–303

Tuck I, Johnson SC, Kuznetsova MI, et al. (2012) Sacred healing stories told at the end of life. J Holist Nurs 30(2):69–80

Elizabeth S, Menkin ES (2010) Nourishment while fasting. J Palliat Med 13(10):1288–1289

Centeno C, Sanz A, Bruera E (2004) Delirium in advanced cancer patients. Palliat Med 18(3):184–194

de Rooij SE, Schuurmans MJ, van der Mast RC, et al. (2005) Clinical subtypes of delirium and their relevance for daily clinical practice: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 20(7):609–615

Lawlor PG, Nekolaichuk C, Gagnon B, et al. (2000) Clinical utility, factor analysis, and further validation of the memorial delirium assessment scale in patients with advanced cancer: assessing delirium in advanced cancer. Cancer 88(12):2859–2867

Spielberger C (1983) Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Consulting Psychologist Press, Palo Alto, CA

Downey L, Engelberg RA, Curtis JR, et al. (2009) Shared priorities for the end-of-life period. J Pain Symptom Manag 37(2):175–188

Delgado-Guay MO, Hui D, Parsons HA, et al. (2011) Spirituality, religiosity, and spiritual pain in advanced cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 41(6):986–994

True G, Phipps EJ, Braitman LE, et al. (2005) Treatment preferences and advance care planning at end of life: the role of ethnicity and spiritual coping in cancer patients. Ann Behav Med 30:174–179

Moadel A, Morgan C, Fatone A, et al. (1999) Seeking meaning and hope: self-reported spiritual and existential needs among an ethnically diverse cancer patient population. Psycho-Oncology 8(5):378–385

Abba K, Horton S, Zammit R, et al. (2015) PA17 interventions to improve upstream communication about death and dying. BMJ Support Palliat Care 5(1):A24

Dobrina R, Vianello C, Tenze M, et al. (2016) Mutual needs and wishes of cancer patients and their family caregivers during the last week of life: a descriptive phenomenological study. J Holist Nurs 34(1):24–34. doi:10.1177/0898010115581936

Conill C, Verger E, Henriquez I, et al. (1997) Symptom prevalence in the last week of life. J Pain Symptom Manag 14(6):328–331

Khan SA, Gomes B, Higginson IJ (2014) End-of-life care: what do cancer patients want? Nat Rev Clin Oncol 11(2):100–108

Montoya-Juarez R, Garcia-Caro MP, Campos-Calderon C, et al. (2013) Psychological responses of terminally ill patients who are experiencing suffering: a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud 50(1):53–62

Booij SJ, Tibben A, Engberts DP, et al. (2014) Wishes for the end of life in Huntington’s disease: the perspective of European physicians. J Huntington’s Dis 3(3):229–232

Fleming R, Kelly F, Stillfried G (2015) “I want to feel at home”: establishing what aspects of environmental design are important to people with dementia nearing the end of life. BMC Palliat Care 14:26

Towsley GL, Hirschman KB, Madden C (2015) Conversations about end of life: perspectives of nursing home residents, family, and staff. J Palliat Med 18(5):421–428

American Religious Identification Survey. Available from http://www.americanreligionsurvey-aris.org/. Accessed 20 July 2015

Balboni T, Vanderwerker L, Block S, et al. (2007) Religiousness and spiritual support among advanced cancer patients and associations with end-of-life treatment preferences and quality of life. J Clin Oncol 25:550–560

Acknowledgments

The list of goals and values on the cards, the game instructions, and information for ordering the cards are available on the Coda Alliance website: www.codaalliance.org.

Dr. E. Bruera is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health grants R01NR010162-01A1, R01CA122292-01, and R01CA124481-01.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Our randomized controlled trial was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Delgado-Guay, M.O., Rodriguez-Nunez, A., De la Cruz, V. et al. Advanced cancer patients’ reported wishes at the end of life: a randomized controlled trial. Support Care Cancer 24, 4273–4281 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3260-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3260-9