Abstract

Purpose

The support needs of cancer patients vary according to the phase of their cancer journey. Recent developments in healthcare are such that the advanced cancer phase is increasingly experienced as a chronic illness phase, with consequent changes in patient support needs. Understanding these needs, and identifying areas of unmet need, can enable us to develop services that are more adequate to the task of supporting this population.

Methods

We conducted a systematic search of four electronic databases to identify studies examining the unmet needs of people living with advanced cancer. Relevant data were extracted and synthesised; meta-analyses were conducted to obtain pooled estimates for prevalence of needs.

Results

We identified 23 studies (4 qualitative) for inclusion. Unmet needs were identified across a broad range of domains, with greatest prevalence in informational (30–55 %), psychological (18–42 %), physical (17–48 %), and functional (17–37 %) domains. There was considerable heterogeneity amongst studies in terms of methods of assessment, coding and reporting of needs, respondent characteristics, and appraised study quality.

Conclusions

Heterogeneity made it difficult to compare across studies and inflated confidence intervals for pooled estimates of prevalence—we need standardised and comprehensive approaches to assessment and reporting of unmet needs to further our understanding. Nonetheless, the review identified prominent needs across a range of (interacting) experiential domains. Moreover, by focussing on unmet needs for support, we were able to extrapolate potential implications for service development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Efforts to improve the care made available to people with cancer have been advanced by formal and purposive assessments of patient needs [1]. Application of purposive needs assessments is a relatively recent development, concomitant with the turn towards patient-centred care, representing a shift from treatment of disease towards supporting people to cope with their experience of cancer [2]. This shift is characterised by a more holistic conceptualisation of care requirements—across physical, psychological, social, spiritual, and informational domains—and a particular focus on the priorities of patients and their loved ones. Assessing needs with this level of specificity has potential to directly inform the development and delivery of person-and-family-centred care—in contrast to assessments that focus on more global scaling of problems, quality of life, or satisfaction [3]. Although these latter constructs can be valuable as broad indicators of patient experience or outcome, they are not informative about (1) underlying causes or targets for change, (2) relative importance to the patient, or (3) whether help is desired/already in place. In the context of supportive care, unmet needs reflect incongruity between the supports that an individual perceives to be necessary versus the actual supports provided. Consistent with patient-centred principles of modern healthcare, unmet needs are thus self-defined: reflecting the wishes of the individual rather than clinician judgments or interpretations of global wellbeing measures (which may show poor congruence with patient priorities [4]). A specific and conditional understanding of patient-reported unmet needs can be more readily translated into suggestions for improving patient care and outcomes [5] with implications for the design and delivery of care services, reducing unnecessary service-use and associated costs [6].

Patient needs vary according to the stage of their cancer journey [7, 8] and recent developments in healthcare are such that many patients who develop advanced disease experience this phase in a very different way as compared with patients from previous generations [9]. In contrast to the predictable rapid progression that once typified experiences of advanced cancer, this phase can now be characterised by an illness trajectory and prognosis that is relatively long and uncertain [10]. The experience of advanced cancer is increasingly one of living with a long-term condition, which might best be understood in terms of chronic illness models [11]. Conceptualising advanced cancer as a chronic illness has implications for care provision: placing an onus on supporting patient self-management [12, 13] and holistic appreciation of the fluctuating challenges of living with chronicity. This “chronic advanced cancer” phase presents a challenge to cancer service models that have traditionally been predicated on managing acute illness with limited follow-up care or emphasis on patient self-management. Indeed, there is a danger of patients entering a protracted transitional state: between active curative treatment and end-of-life care, wherein the respective responsibilities of outpatient/follow-up and primary care services may be unclear. In view of the changing experience of advanced cancer, and associated potential implications for care provision, it would seem imperative and timely to examine the care needs of patients living with advanced disease.

The present review is distinctive in its focus on unmet needs in advanced cancer. Harrison et al. [2] conducted a systematic review that was inclusive of some of the literature pertaining to this population, but as part of a more general review (across the whole cancer trajectory). Moreover, the current review: updates the literature considered by Harrison et al. (retrieved in June 2006), includes available qualitative research, appraises the quality of retrieved studies (with implications for informing future research designs), and presents pooled weighted estimates of needs prevalence by domain (meta-analysis). By synthesising available information regarding the unmet needs in this population we can identify areas for developing and targeting supportive interventions that best meet the changing needs of this population of patients.

The primary question to be addressed by the review was: What are the unmet care needs of people living with advanced cancer? Secondarily to this, the review aimed to:

-

Describe the specific needs of this population in terms of domain and prevalence, identifying needs that are most commonly reported to be unmet

-

Identify assessments/measures of unmet needs that have been used in the literature

-

Appraise the quality of available evidence in this area

Methods

We conducted a systematic search of four electronic bibliographic databases (CINAHL, Medline, EMBASE, and PsycINFO) during July 2015. When constructing our search statement, we focussed on three key concepts (cancer, advanced disease, and needs) and drew from search statements published by Harrison et al. [2] and Puts et al. [14]. We adapted our search strategy for each database, according to the specific subject headings (thesauri) and limits (categories) used within each database. The final statement was of the following form:

-

Cancer (exp neoplasms, cancer, malignan$, oncolog$)

-

AND advanced disease (advanced disease, metastatic, incurable, exp survivors, exp palliative care, chronic cancer)

-

AND needs (exp needs assessment, unmet need$, need$ assess$, perceived need$, support$ care need$, psycho$ need$, physical need$, exp symptom assessment, information need$)

-

[limit to human, English language, journal]

We additionally examined the reference lists and forward citations for retrieved articles that met our eligibility criteria, so as to identify further relevant articles that may not have been detected by the database searches.

Studies were included if they:

-

Reported data pertaining to a population of adults living with advanced cancer (mixed samples were eligible if >50 % had a diagnosis of advanced cancer).

-

Reported data capturing patient experiences, views, perspectives, or concerns that are directly linked to (or expressed in terms of) an unresolved desire for support/service provision (i.e. unmet care needs)

-

Reported primary data

-

Were published in English

-

Were published in peer-reviewed journals (minimum quality threshold)

Studies were excludedFootnote 1 if they:

-

Reported data for mixed patient samples from which we could not isolate data for the population of interest (adults with advanced cancer).

-

Reported data from patients in the terminal or end-of-life care phase (final weeks/days of life)

-

Reported data from inpatients that only pertained to their acute care needs (as distinct from the needs of living with cancer in community or outpatient contexts)

-

Solely focussed on quality of life, satisfaction, or presence of symptoms/problems

Study selection

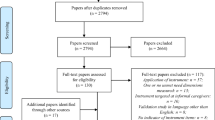

Figure 1 outlines the study selection process. Titles and abstracts were independently screened for inclusion and potentially eligible articles were retrieved for full-text review. Relevant full text articles were reviewed independently by at least two authors; in cases of uncertainty, final decisions on inclusion were made in discussion with the wider team.

Data extraction

We extracted study information using a standardised pro forma; data fields included: authors, year, location, study design, methodology and methods, sample size, response rate, patient demographics, clinical characteristics, findings relating to unmet needs, applied needs assessment approach, and recommended interventions. Extraction forms were checked by a second author and discrepancies were discussed/resolved (with arbitration by a third author as required).

Data analysis

To identify domains of unmet need across quantitative and qualitative studies we applied a content analytic approach to narrative synthesis [15]: Content categories were determined a priori (based on domains of care need identified and distinguished in previous literature [e.g. 2] including physical, psychological, and informational domains) and study data were parsed and categorised with respect to these categories. For quantitative studies that reported the prevalence of unmet needs by domain, we were able to pool proportions and conduct a meta-analysis. For each domain of need, we identified all studies reporting the presence of one or more unmet needs in that domain and extracted the peak proportion (i.e. if a study reported multiple items of unmet need in a given domain, with varying levels of endorsement for each need, we extracted the most endorsed item to represent that domain). We used MedCalc software to transform the extracted data (applying the Freeman-Tukey arcsine square root transformation) and calculate weighted summary proportions (with respective 95 % CIs) for each domain. Given heterogeneity of estimates, we applied random-effects models. We limited meta-analysis to quantitative studies that applied comprehensive (multiple domain) needs assessments: This was to ensure some comparability between pooled studies, and to avoid inflation of estimates that may arise from targeted assessment in a single domain.

Quality assessment

For each included study, methodological quality was independently appraised by two authors—in accordance with PRISMA recommendations [16]. To accommodate our inclusion of a range of study designs, we applied the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT; [17]). The MMAT has been found to have good inter-rater reliability and demonstrable validity as a framework for quality appraisal [18]. For a given research design, the MMAT enables evaluation against four criteria—yielding a quality rating between 0 (no criteria met) and 4 (all criteria met). We did not use ratings of study quality as a basis for study exclusion; rather, we assessed quality to identify areas for strengthening in future research and enable some interpretive weighting of findings according to study quality.

Results

Study characteristics

Of the 23 included studies, 5 were conducted in the UK, 5 in the USA, 4 in Australia, 3 in Canada, 2 in the Netherlands, and 1 each in Hong Kong, Japan, Italy, and Denmark. Most (19) of the studies employed quantitative surveys (using highly structured methods in questionnaire or interview modalities); 4 were qualitative studies (using semi-structured interviewing, in individual or focus group formats). In studies using quantitative designs, the most commonly applied assessment of unmet needs was the Supportive Care Needs Survey (SCNS; used in six studies)—although there were inconsistencies between studies in how this measure was used (adaptations to questionnaire length, items, dimensionality, and language). The Needs Assessment for Advanced Cancer Patients (NA-ACP) and Problems and Needs in Palliative Care Questionnaire (PNPC) were each used in two studies, with other studies using bespoke survey instruments.

The studies had between 11 and 629 participants (3613 participants in total) with response rates ranging from 32 % to 98 %. Across studies, the average age of participants ranged from 57 to 75. Fifteen studies included a mixed cancer population (various sites), three focussed on women with breast cancer, three focussed on men with prostate cancer, one focussed on patients with lung cancer, and one focussed on women with ovarian cancer.

Most (13) studies applied a multidimensional approach to assessing needs (enquiring across a range of domains); of the remaining studies, 5 focussed on the informational domain, 4 focussed on the Activities of Daily Living (ADL) domain (encompassing both basic and instrumental ADL), and 1 focussed on the spiritual domain. Table 1 presents study characteristics and synthesised findings with respect to domains of unmet need.

Estimated prevalence of unmet needs by domain

For the 11 quantitative studies that assessed unmet needs across multiple domains, we computed weighted summary estimates of peak prevalence (%).Footnote 2 Estimates were highly variable between studies but 95 % CIs provide a plausible range of estimates for average prevalence of needs in the advanced cancer population. Ordered by the lower bound of estimates, the domains of greatest unmet need were informational (30–55 % prevalence), psychological (18–42 %), ADL (17–37 %), and physical (17–48 %). Ordered by point estimates, the domains of greatest unmet need were informational (42 %), patient care and support (33 %), physical (32 %) and psychological (29 %)—however, the point estimate for patient care and support is unreliable (95 % CI for this estimate ranges from 3 to 77 %; reflecting that the pooled estimate was based on a small sample, taken from two studies that were highly inconsistent in their estimates [14 % versus 56 %]). Table 2 shows the results of the meta-analysis. All of the quantitative studies that applied multidimensional assessments identified unmet needs in the psychological domain; physical, ADL, and informational needs were similarly prominent.

Prominent specific needs

To identify specific needs that were commonly unmet, we selected a sub-sample of retrieved studies—those using the SCNS (n = 6)—and extracted the most frequently reported items by domain. Limiting analysis to studies using the SCNS allowed for some comparability of specific need items across studies. Table 3 depicts the results. Primary needs in each of the common domains were: loss of previous functional ability (ADL); fatigue and pain (physical); being informed about self-care and having a professional contact with whom to discuss concerns (health system and informational); and illness-related fears and concerns about close others (psychological).

Quality of evidence

Quality of the 23 included studies was assessed against the MMAT criteria (see Table 4). Most (68 %) were of a high standard (all criteria met) with respect to the appraisal framework. Recurrent methodological limitations of the quantitative studies were low response rate (<60 %) and questionable sample representativeness. Low response rate can raise questions regarding representativeness (i.e. these criteria can be interdependent) but two of the five studies with a lower response rate were able to demonstrate that there were no systematic differences between responders and non-responders. One qualitative study did not report consideration of how findings might have been shaped by the researchers’ positioning or the context within which data were collected, making it more difficult for the reader to interpret reported findings (e.g. in terms of whose perspectives they represent and how well they would transfer to other contexts or settings). It should be emphasised that appraisals reflect reporting of research rather than the research itself (decisions with respect to criteria can only be made on the basis of article content, which may not wholly represent methodological qualities).

Discussion

This review identified 23 primary studies evidencing the unmet needs of patients living with advanced cancer. Below we summarise and critically interpret findings in relation to the aims of the review, before drawing conclusions and making recommendations for future research.

Domains of unmet need

In studies that took a broad approach to the question of unmet needs (applying multidimensional measures or open interviewing procedures) patients reported a desire for additional help across a range of domains: psychological or psychosocial, physical, functional (activities of daily living; ADL), informational and health system, patient care and support, economic, spiritual, and sexuality. Of the 13 studies that applied a multidimensional approach (11 quantitative [3, 19–22, 26, 27, 31, 32, 37] and 2 qualitative [23, 34]), all identified unmet needs in the domain of psychological experience (n = 13), and most identified needs in informational (n = 11), physical (n = 11), and functional (n = 11) domains.

Separation into different domains may detract from the likely interconnectedness of needs across domains. For example, reported information needs may represent efforts to manage worry/anxiety associated with the uncertainty and complexity of living with advanced cancer. In such cases, resolving information needs may secondarily assuage psychological needs. However, it may often not be possible to provide the information (or certainty) that a patient is seeking; here, psychological support may be the more practicable means of intervening (coping with uncertainty and associated anxiety) and secondarily reduce needs for information. Similarly, direct support with ADL may help to compensate for loss of functioning, but intervention could also focus on cognitive and behavioural strategies (e.g. reappraisal and self-pacing) to ameliorate frustration and improve patient self-management. Viewed within a framework of chronic illness, it may be preferable to foster emotion-focused coping (managing response to stressors) as opposed to problem-focused coping (attempting to eliminate stressors): There is evidence that emotion-focussed coping can be particularly adaptive when faced with a condition that is uncontrollable or chronic (where problem-focussed coping may be counterproductive and lead to loss of hope; e.g. [40]). In other respects, the attribution of a need to one category or another is often misleading (for example, the experience of fatigue is likely better conceptualised as biopsychosocial than “physical” per se; [41]).

Ten studies were more circumscribed in their focus [24, 25, 28–30, 33, 35, 36, 38, 39], conducting targeted assessment of needs in just one or two domains. Apart from one study pursuing spiritual needs [30], these studies targeted assessment of either informational or functional needs. There appeared to be a temporal trend, with more recent studies tending to employ more holistic assessments: of studies published in the past ten years (post-2005), 90 % (9/10) applied a multidimensional approach—as compared with 31 % (4/13) of earlier studies. It is likely that the shift towards more holistic conceptualisation and assessment of needs reflects a broader shift in conceptualising and assessing care needs (caring for the “whole person;” [42]). It is also possible that the changing experience of advanced cancer (increasingly one of living with chronic illness) has led to some domains of need gaining new prominence. However, it is difficult to distinguish changes in need from changes in assessment; understanding of patient experiences is somewhat determined by the questions that are asked (or not asked). This is a limitation for all studies, but makes it particularly difficult to integrate findings from unidimensional studies with those from multidimensional studies: for example, across the 23 reviewed studies as a whole, informational and functional needs were most recurrent, but it is unclear whether the prominence of these domains is driven by patients or researchers (e.g. the common and singular focus on informational and ADL needs in studies from the 1980s and 1990s might have been responsive to patient priorities of the time, or might reflect the particular interests of the researchers who were then investigating needs of people with advanced cancer).

Prevalence of unmet needs

Examining evidence (from quantitative studies) for prevalence of needs, there was clear variability within and between domains—and across studies. Variability within domains indicates the value of detailed individualised assessment. Within a given area, preferences for additional input might differ greatly according to the particular item of need. Taking the example of information seeking, Wong [39] found that needs varied from 14 to 75 % according to the topic area, and this would seem to have important implications for targeted changes in information provision: some topics appear to be priority areas for immediate improvement (those for which most patients have unmet needs) but there is also an apparent necessity to individualise provision (there was no topic for which all respondents desired additional information—uniform increases in information provision might overwhelm patients for whom current provision is sufficient).

Variability in prevalence of needs between domains is indicative of the relative sufficiency of care provision in those domains. For example, Uchida et al. [37] found high levels of unmet need in the psychological domain (peak prevalence of 79 %) as compared with the sexuality domain (15 %). A focus on frequency or prevalence can be misleading: a low-frequency unmet need may be highly salient and clinically important for the few individuals who experience that need (and individual ranking of needs may differ considerably from the aggregate ranking of needs based on prevalence). Nonetheless, domains with higher prevalence needs would seem to be areas wherein service provision is commonly experienced as insufficient—highlighting general targets for improving services to this population. Based on pooled estimates of peak prevalence (95 % CIs) from quantitative studies applying multidimensional needs assessments, unmet needs were most prevalent in informational (30–55 %), psychological (18–42 %), physical (17–48 %), and functional (17–37 %) domains. In terms of particular items of need, psychological needs were commonly for help managing worries (about disease progression and impact on close others) with fear and anxiety emerging as prominent emotional needs. Common items of need emerging across other domains included needs relating to information about self-care (informational), fatigue (physical), and difficulty maintaining previous activities (functional loss).

Variability in prevalence between studies (reflected in the wide confidence intervals for pooled prevalence estimates) is likely attributable to the heterogeneity of these studies. In particular, heterogeneity in time and place complicates comparison across studies: culture and service differences may account for a large proportion of variance in reporting of unmet care needs (in terms of both the needs that are prioritised and the likelihood that needs are being addressed [43]). The comparability of needs in the earlier versus later studies reviewed is questionable given that, in the context of recent treatment advances, the trajectory of advanced cancer is changing. As discussed in the introduction, advanced cancer is increasingly experienced as an ongoing complex condition requiring long-term monitoring, intervention, and supportive care [9] and we would expect this to be reflected in shifting care needs. Inconsistency in approaches to assessing unmet needs was another important source of heterogeneity, as discussed in the next section.

Assessment of unmet needs

The reviewed studies used a range of approaches to defining and assessing needs—most studies used idiosyncratic, bespoke, or adapted approaches that made external comparisons difficult. The SCNS was the most commonly applied assessment—used in six studies [8, 20–22, 26, 37]—but even studies applying the SCNS used different variants of the tool (e.g. 34-item [22] versus 61-item [26] versions); classified needs in different ways (e.g. coding of some items as “spiritual” [26] versus “psychological” [21]); and applied different thresholds for identifying a need as “unmet” (e.g. whether “low” levels of need were considered to be unmet needs [37] or not [8]). As discussed above, measurement approaches and assumptions construct and constrain the needs that can be identified: this is most obviously the case in studies that purposively focussed on a single domain of need but even “comprehensive” assessments like the SCNS arguably neglect some aspects of wellbeing (e.g. spiritual, cultural, and occupational needs).

Some of the reviewed studies illustrated clear dissociations between reported “problems” versus “needs” [3]. In areas where patients appear to be struggling or suffering but do not identify needs for supportive care, divergent interpretations could be made. Assuming patients are able and willing to direct their care (as “health consumers”) problem-need dissociations may be taken to reflect a patient’s wishes to prioritise other areas or preference to draw on alternative sources of support in that domain—and we found evidence that patients can explicitly identify problems that they do not wish to receive professional help with [31]. However, dissociations could also reflect a lack of awareness regarding available supports (e.g. misperception that some domains may be outside the remit of care providers) or minimisation of difficulties and self-subjugation (e.g. [34]).

Quality appraisal

Most studies met the majority of applied quality criteria. For quantitative descriptive studies, response rates were somewhat limited by characteristics of the target population: poor/unpredictable health limited response rate in some studies (and led to substantial attrition in studies employing longitudinal designs). Related to this, representativeness—and so, generalisability—was restricted by non-participation of individuals with poorer health/functioning (this may have led to systematic under-estimation of needs). Studies also tended to exclude individuals on the basis of language ability. To improve generalisability, some studies used random sampling (e.g. [37]), or compared responders with non-responders (e.g. [3]) or reference populations (e.g. [8]) to gauge potential selection biases. Two of the four qualitative studies did not explicate reflexivity; it was thus not clear how extracted data were influenced by the researchers’ own perspectives and positioning in these studies. For our purposes, the methodological issue that most limited our ability to address our review question was inconsistency between studies (in how they assessed and coded for unmet needs) which was beyond the scope of individual study appraisal; this was compounded by variation and selectivity in reporting (e.g. some studies reported findings comprehensively (e.g. [37]) whereas others focussed on “top 10” items of need (e.g. [8]), limiting the comparability of information across studies).

Conclusions

By definition, unmet needs are somewhat context-bound—the extent to which needs are met will depend on the particular service provisions in a given setting. This is reflected in the inconsistencies across reviewed studies and suggests that investigation of unmet needs is best conducted and interpreted at “local” levels, where direct implications for service delivery will be clearest. Nonetheless, our synthesis of available evidence has general implications for developing and testing interventions that can address recurrent needs for people living with advanced cancer: (1) information deficits, (2) preoccupation with worries/uncertainties, (3) fatigue and pain management, and (4) loss of functioning. If shown to be generalizable/transferrable, interventions for these concerns could be implemented at local levels according to contextual needs. A feature of the most prominent needs is that they are difficult to eliminate or “problem-solve” and may require more accommodative coping (secondary control versus primary control; e.g. [44])—in this respect, they resemble prominent needs in chronic illness conditions (consistent with a broader shift in experiences of advanced cancer). There is a need now for interventional studies demonstrating that assessed “unmet needs” can be addressed: evidence to date for the efficacy of interventions targeting unmet needs is weak [45] and questions remain with respect to whether this reflects limitations of needs assessment tools, broader methodological flaws, ineffectiveness of available interventions, or the inherent difficulty of “meeting” some expressed needs. The value of descriptive needs assessments ultimately rests on their ability to successfully inform intervention.

Notes

In order to capture everyday needs of people living with advanced disease, we focussed on the chronic phase: i.e. we excluded patients considered to be at the end-stage of cancer (following the definition of chronic advanced cancer by Harley et al. [11]) or reporting acute needs at points of inpatient admission. Although increasingly experienced and recognised [11] we found (in initial scoping searches) that few studies used consistent terms or definitions to describe the pre-end-stage phase of advanced cancer; consequently, we used a broadly sensitive search but then applied exclusion criteria to enable sufficient specificity.

Eight of the quantitative studies primarily assessed needs in a single domain and were not included in the meta-analysis (which was restricted to studies applying multidimensional needs assessments).

References

McDowell ME, Occhipinti S, Ferguson M, Dunn J, Chambers S (2010) Predictors of change in unmet supportive care needs in cancer. Psycho-Oncology 19:508–516

Harrison JD, Young JM, Price MA, Butow PN, Solomon MJ (2009) What are the unmet supportive care needs of people with cancer? A systematic review. Support Care Cancer 17:1117–1128

Rainbird K, Perkins J, Sanson-Fisher R, Rolfe I, Anseline P (2009) The needs of patients with advanced, incurable cancer. Br J Cancer 101:759–764

Snyder CF, Dy SM, Hendricks DE, Brahmer JR, Carducci MA, Wolff AC, Wu AW (2007) Asking the right questions: investigating needs assessments and health-related quality-of-life questionnaires for use in oncology clinical practice. Support Care Cancer 15:1075–1085

Valery PC, Powell E, Moses N, Volk ML, McPhail SM, Clark PJ, Martin J (2015) Systematic review: unmet supportive care needs in people diagnosed with chronic liver disease. BMJ open 5:e007451

Lam WW, Au AH, Wong JH, Lehmann C, Koch U, Fielding R, Mehnert A (2011) Unmet supportive care needs: a cross-cultural comparison between Hong Kong Chinese and German Caucasian women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 130:531–541

Sanson-Fisher R, Girgis A, Boyes A, Bonevski B, Burton L, Cook P (2000) The unmet supportive care needs of patients with cancer. Cancer 88:226–237

Waller A, Girgis A, Johnson C, Lecathelinais C, Sibbritt D, Forstner D, Liauw W, Currow DC (2012) Improving outcomes for people with progressive cancer: interrupted time series trial of a needs assessment intervention. J Pain Symptom Manag 43:569–581

Phillips JL, Currow DC (2010) Cancer as a chronic disease. Collegian 17:47–50

Thorne SE, Oliffe JL, Oglov V, Gelmon K (2013) Communication challenges for chronic metastatic cancer in an era of novel therapeutics. Qual Health Res 23:863–875

Harley C, Pini S, Bartlett YK, Velikova G (2012) Defining chronic cancer: patient experiences and self-management needs. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2:248–255

Coulter A, Roberts S, Dixon A (2013) Delivering better services for people with long-term conditions: building the house of care. The King’s Fund, London

Wagner E (1998) Chronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness? ECP 1:2

Puts M, Papoutsis A, Springall E, Tourangeau A (2012) A systematic review of unmet needs of newly diagnosed older cancer patients undergoing active cancer treatment. Support Care Cancer 20:1377–1394

Snilstveit B, Oliver S, Vojtkova M (2012) Narrative approaches to systematic review and synthesis of evidence for international development policy and practice. J Dev Effect 4:409–429

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 151:264–269

Pluye P, Robert E, Cargo M, Bartlett G, O’Cathain A, Griffiths F, Boardman F, Gagnon M, Rousseau M (2011) Proposal: A mixed methods appraisal tool for systematic mixed studies reviews. McGill University, Montréal, pp. 1–8

Souto RQ, Khanassov V, Hong QN, Bush PL, Vedel I, Pluye P (2015) Systematic mixed studies reviews: updating results on the reliability and efficiency of the mixed methods appraisal tool. Int J Nurs Stud 1:500–501

Anderson H, Ward C, Eardley A, Gomm S, Connolly M, Coppinger T, Corgie D, Williams J, Makin WP (2001) The concerns of patients under palliative care and a heart failure clinic are not being met. Palliat Med 15:279–286

Aranda S, Schofield P, Weih L, Yates P, Milne D, Faulkner R, Voudouris N (2005) Mapping the quality of life and unmet needs of urban women with metastatic breast cancer. Eur J cancer care 14:211–222

Au A, Lam W, Tsang J, Tk Y, Soong I, Yeo W, Suen J, Ho WM, Ky W, Kwong A (2013) Supportive care needs in Hong Kong Chinese women confronting advanced breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology 22:1144–1151

Beesley VL, Price MA, Webb PM, O’Rourke P, Marquart L, Butow PN (2013) Changes in supportive care needs after first-line treatment for ovarian cancer: identifying care priorities and risk factors for future unmet needs. Psycho-Oncology 22:1565–1571

Carter N, Bryant-Lukosius D, DiCenso A, Blythe J, Neville AJ (2011) The supportive care needs of men with advanced prostate cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 38:189–198

Christ G, Siegel K (1990) Monitoring quality-of-life needs of cancer patients. Cancer 65:760–765

Dale J, Jatsch W, Hughes N, Pearce A, Meystre C (2004) Information needs and prostate cancer: the development of a systematic means of identification. BJU Int 94:63–69

Fitch MI (2012) Supportive care needs of patients with advanced disease undergoing radiotherapy for symptom control. Can Oncol Nurs J /Revue canadienne de soins infirmiers en Oncologie 22:84–91

Hwang SS, Chang VT, Cogswell J, Alejandro Y, Osenenko P, Morales E, Srinivas S, Kasimis B (2004) Study of unmet needs in symptomatic veterans with advanced cancer: incidence, independent predictors and unmet needs outcome model. J Pain Symptom Manag 28:421–432

Mor V, Guadagnoli E, Wool MS (1987) An examination of the concrete service needs of advanced cancer patients. J Psychosoc Oncol 5:1–17

Mor V, Masterson-Allen S, Houts P, Siegel K (1992) The changing needs of patients with cancer at home. A longitudinal view. Cancer 69:829–838

Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, Worth A, Benton TF (2004) Exploring the spiritual needs of people dying of lung cancer or heart failure: a prospective qualitative interview study of patients and their carers. Palliat Med 18:39–45

Osse BH, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, Schadé E, Grol RP (2005) The problems experienced by patients with cancer and their needs for palliative care. Support Care Cancer 13:722–732

Passalacqua S, Di Rocco ZC, Di Pietro C, Mozzetta A, Tabolli S, Scoppola A, Marchetti P, Abeni D (2012) Information needs of patients with melanoma: a nursing challenge. Clin J Oncol Nurs 16:625–632

Siegel K, Mesagno FP, Karus DG, Christ G (1992) Reducing the prevalence of unmet needs for concrete services of patients with cancer. Evaluation of a computerized telephone outreach system. Cancer 69:1873–1883

Soelver L, Rydahl-Hansen S, Oestergaard B, Wagner L (2014) Identifying factors significant to continuity in basic palliative hospital care—from the perspective of patients with advanced cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol 32:167–188

Templeton H, Coates V (2003) Informational needs of men with prostate cancer on hormonal manipulation therapy. Patient Educ Couns 49:243–256

Tomlinson K, Barker S, Soden K (2012) What are cancer patients’ experiences and preferences for the provision of written information in the palliative care setting? A focus group study. Palliat Med 26:760–765

Uchida M, Akechi T, Okuyama T, Sagawa R, Nakaguchi T, Endo C, Yamashita H, Toyama T, Furukawa TA (2010) Patients’ supportive care needs and psychological distress in advanced breast cancer patients in Japan. Jpn J Clin Oncol: hyq230

Voogt E, van Leeuwen AF, Visser AP, van der Heide A, van der Maas PJ (2005) Information needs of patients with incurable cancer. Support Care Cancer 13:943–948

Wong RK, Franssen E, Szumacher E, Connolly R, Evans M, Page B, Chow E, Hayter C, Harth T, Andersson L (2002) What do patients living with advanced cancer and their carers want to know?—a needs assessment. Support Care Cancer 10:408–415

Montero-Marin J, Prado-Abril J, Demarzo M, Gascon S, Garcıa-Campayo J (2014) Coping with stress and types of burnout: explanatory power of different coping strategies. PLoS One 9:e89090

Bensing JM, Hulsman RL, Schreurs KM (1999) Gender differences in fatigue: biopsychosocial factors relating to fatigue in men and women. Med Care 37:1078–1083

Adler NE, Page AE (2008) Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs. National Academies Press, Washington DC

Fielding R, Lam WWT, Shun SC, Okuyama T, Lai YH, Wada M, Akechi T, Li WWY (2013) Attributing variance in supportive care needs during cancer: culture-service, and individual differences, before clinical factors. PLoS One 8:e65099

Compas BE, Jaser SS, Dunn MJ, Rodriguez EM (2012) Coping with chronic illness in childhood and adolescence. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 8:455

Carey M, Lambert S, Smits R, Paul C, Sanson-Fisher R, Clinton-McHarg T (2012) The unfulfilled promise: a systematic review of interventions to reduce the unmet supportive care needs of cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 20:207–219

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This work was supported by Research Capability Funding from the National Institute of Health Research, awarded via CityCare.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. None of the authors has a financial relationship with any organisation for which this research would present a conflict of interest. The data were in the hands of the authors at all times and are available to the journal upon request.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Moghaddam, N., Coxon, H., Nabarro, S. et al. Unmet care needs in people living with advanced cancer: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 24, 3609–3622 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3221-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3221-3