Abstract

Purpose

The expanded prostate cancer index composite-26 (EPIC-26) instrument is a validated research tool used for capturing patient-reported quality-of-life outcomes related to the domains of bowel, bladder, and sexual functioning for men undergoing curative treatment for prostate cancer. The purpose of this pilot study was to explore the perceptions and experiences of clinicians with using EPIC-26 in a clinical setting for patients receiving curative radiotherapy.

Methods

Ten clinicians reviewed EPIC-26 scores either before or during weekly clinical encounters with patients receiving curative radiation treatment for prostate cancer. After a period of 2 months, clinicians underwent individual semi-structured interviews where they were asked about their views on measuring patient-reported outcomes in practice, the value of EPIC-26, impressions on patient acceptability, and operational issues.

Results

There was a general willingness and acceptance by clinicians to use EPIC-26 for routine clinical practice. Clinician participants found EPIC-26 to be generally informative, and added value to the clinical encounter by providing additional information that was specific to prostate cancer patients. EPIC-26 was also felt to improve overall communication and provide additional insight into the patient experience.

Conclusions

Our qualitative findings suggest that there may be a role for incorporating patient-reported outcome measure assessment tools like EPIC-26 routinely into clinical practice. However, further qualitative and quantitative research is required in order to assess the impact of patient-reported outcome information on communication, patient and clinician satisfaction, and how these and other related outcomes can be used for guiding treatment decision-making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The widespread use of serum prostate-specific antigen measurement has led to an increasing proportion of patients being diagnosed with localized prostate cancer. While large randomized trials are lacking, retrospective population-based studies suggest that men experience similar overall survival regardless of treatment modality [1]. However, quality-of-life research has demonstrated that functional outcomes relating to urinary incontinence, bowel functioning, and sexual activity have treatment-specific patterns and are important drivers of patient satisfaction in the long term [2–5].

Evaluation of these patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in the clinical setting has been shown to improve communication between caregivers and patients and to inform the medical encounter [6–11]. The use of PROs in the clinical setting has been postulated to further provide improvements to the quality of care by functioning as an aid in detecting overlooked problems, improving a patient’s ability to describe their problems, and monitoring treatment effects [12, 13]. Therefore, the systematic evaluation of these PRO measurement tools in a clinical setting is necessary prior to their incorporation into routine practice.

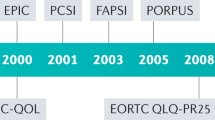

Through its Cancer Symptom Management Collaborative, Cancer Care Ontario has implemented the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS) as a standard of care for all patients receiving cancer care within the province [14, 15]. The ESAS instrument uses Likert scales to evaluate nine symptoms common in patients with advanced cancers (such as pain and shortness of breath). However, prostate cancer-specific functional outcomes are not captured by this tool, and therefore, there has been an interest in using site-specific PRO measurement instruments in conjunction. Research on the value of using such instruments in clinical practice is sparse (particularly for prostate-specific instruments), and a lack uptake of PROs in urological clinical practice threatens the realization of the general benefits of PROs illustrated by randomized clinical trials of their implementation [12].

The main aim of this pilot study was to explore the perceptions and experiences of clinical staff using a patient-reported, prostate cancer-specific PRO measurement instrument in clinical practice for patients receiving curative radiotherapy. A secondary aim was to ensure patient acceptability of the process. We selected the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC-26) instrument, a 26-item instrument validated for capturing PROs related to the domains of bowel, bladder, sexual functioning as well as the impact of hormonal therapy in patients with localized prostate cancer [11]. Use of the EPIC-26 tool was hypothesized to add value to the clinical encounter through the collection of individual level data and by summarizing trends in patient-reported outcomes over time. The purpose of this study was to pilot-test the use of EPIC-26 in a clinical context in order to assess the acceptability and added value of measuring EPIC-26 scores in practice from clinician and patient perspectives. Our focus was on the perspective of clinicians, as we were interested in a “signal” of clinical interest that could be used to justify a larger scale, multi-institutional feasibility study in Ontario. We also provide preliminary feedback from patient participants.

Methods

Study participants

Review boards at the hospital and university approved the study, which was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Target study participants included clinicians (genitourinary radiation oncologists, senior residents, and radiotherapy nurse care providers) and their patients at an ambulatory cancer center in Ontario. Eligible patients were English-speaking patients undergoing a radical course of external beam radiation therapy for prostate cancer. Consecutive patients were approached for participation unless their attending oncologist indicated they were not suitable for study inclusion.

Procedure

Patients provided consent to enroll in the study and completed an electronic version of the EPIC-26 at weekly intervals over the course of 2 months using a touch-screen computer, with the aid of a research assistant as required. Scores were collated and grouped into urinary obstructive/irritative, urinary incontinence, bowel function, sexual, and hormonal domains, as per the EPIC-26 scoring documentation. Clinicians were asked to review their patient’s EPIC printouts (Fig. 1) either before or during each patient encounter.

Clinician interviews

Following the period of data collection, semi-structured interviews were performed with each clinician. The clinician interview guide was developed by a panel consisting of a resident, radiation oncologist and a cognitive psychologist with a background in qualitative research. Key themes for exploration were identified by consensus and used to create the final interview guide, which included the following: questions eliciting attitudes toward measuring PROs in practice, perceptions of the value of EPIC-26 questionnaire, value of the summary domain scores, impressions of patient acceptability and value, and operational issues (Fig. 2). The interviews were semi-structured, commencing with open-ended questions using prompts as necessary, and were recorded [16]. Participants were interviewed individually in order to encourage unbiased feedback, and all responses were collated and anonymized. Neutrality was maintained by the interviewer who stressed the importance of both positive and negative aspects of participants’ experience.

Patient interviews

Patient evaluations consisted of an informal debriefing interview with the study coordinator, which addressed patients’ comfort with the questionnaire content, perceived value of the process, and overall impressions. The interviews were not recorded/transcribed owing to weekly recurring assessments and feasibility considerations. Verbatim quotations, therefore, are not available. The frequency of missing items was not systematically recorded. Additionally, ad hoc patient comments regarding their perceptions of the tool, such as their comments on ease of use and sources of confusion, were recorded over the course of the study.

Data analysis

All clinician interviews were transcribed verbatim and reviewed to ensure transcriptional accuracy. A thematic content analysis was performed by applying the framework described by Pope et.al. [17]. Transcriptions and recordings were reviewed multiple times to ensure that study staff became familiarized with the data. Codes and categories were created to capture reoccurring patterns in the textual data. Categories that shared a common meaning were brought together as preliminary themes in an index. This index was then reapplied to all data, and themes were refined as further associations emerged. These final themes were then analyzed in order to explain study findings.

Results

Feasibility outcomes

All ten clinician participants invited to participate in the program agreed to do so. The clinicians consisted of five radiation oncologists, four nurses, and one resident. There was an equal representation of male and female participants. One clinician participant (C7) who did not regularly use EPIC was included in the analyses. The time between study onset and the interviews ranged from 8 to 13 weeks; the interviews took an average of 16.3 min to complete (range 11.1–22.6 min).

Among the 10 clinicians, all of their 81 eligible patients receiving radiotherapy for early-stage prostate cancer were invited to participate in their weekly treatment review sessions with their clinicians. Of these 69 (85.2 %) had repeated assessments as planned; 72 patients initially participated and 3 patients withdrew after the first assessment (all citing lack of familiarity with touch-screen computers). Patients completed the touch-screen assessments within 15 min, and the vast majority did not have difficulties with the touch-screen interface.

Clinician’s perceptions

Theme 1: EPIC 26 provided relevant clinical information

All of the clinicians agreed that there was added value in using PRO measures for clinical practice. There was consensus that PROs are useful in clinical practice because of the additional information they offer. Quotations from the qualitative analyses included:

C1: Any added information you can get on a patient can only be benefit the interaction. We are all only human and even doctors and nurses forget to ask a question sometimes.

C3: Some of us are better at getting facts, while some of us are better at understanding the patient’s experience of their illness and treatment. A tool that fills in any gaps can only add to the interaction itself.

One of the most value-added aspects of EPIC-26 to the patient encounter was that it provided information that was specific to prostate cancer patients. Clinicians felt that other tools available in clinic provide less prostate cancer-specific information and were therefore sometimes less clinically relevant.

C6: It’s great to finally have some site-specific information about our prostate cancer patients while they are on treatment. Often time they are well otherwise and I am most curious about their bowel, bladder and sexual functioning.

C3: With ESAS, many patients would score zeroes even though they had significant proctitis or other symptoms. EPIC focused on areas that were important for men while they are on treatment.

Many clinicians felt that patient-reported information from EPIC-26 was also more accurate than what they could normally elicit during a clinical encounter because patients have more time to think about their responses. Clinicians also had the perception that patients are generally more honest with self-reporting because they do not feel they do not need to please their health-care providers directly.

C10: They [patients] want to do well and they want to please us by doing well. I think sometimes they tell us what we want to hear and not how they are really feeling. With EPIC they don’t feel the pressure to please a clinician and can answer honestly.

C5: Sometimes patients misinterpret what we are asking them. But if they read it themselves, have a chance to think about it, there is less room for error. I think they exert more effort into understanding and therefore we are getting more accurate information.

Theme 2: an improved clinical encounter

Many clinicians felt that EPIC-26 helped to improve the patient experience beyond providing additional objective information. By aiding in communication and providing insight into the patient-experience, clinician participants felt that EPIC helped to make clinical encounters more efficient and relevant to a specific patient’s needs. Many clinicians felt that reviewing scores with patients helped to identify key patient issues, which they could then spend more time exploring. Others felt that it also helped to identify patients who were doing well, so they could spend time of other topics of importance to their patient.

C1: When you would see an outlier, you could immediately tell there was a problem that was out of proportion to everything else. I could tell a patient that, “I see your scores in the sexuality domain are lower than in others. I have forgotten that this is a problem for you.”

C9: It didn’t necessarily change what I asked patients, but maybe the order. It helped me to prioritize my patient’s needs and I could see they appreciated that... You never felt like you were leaving something important to the end and rushing as a result.

Another dimension of improved communication was that many clinicians felt that EPIC-26 data provided more accurate descriptions of what the patient was experiencing. The information on “patient bother” provided health-care workers with an additional perspective on the meaning that symptoms may have for patients.

C10: I was really surprised by some patient scores. Some men had significant urinary symptoms, but did not seem bothered by them, as indicated by their scores…Knowing the meaning symptoms have for a patient can really affect your clinical decision-making.

C2: I think patients may hide how they are feeling about symptoms because they want to please the clinician. They don’t want you to think that you made them feel bad. If you were to ask them directly, they may downplay the bother. Having ‘bother’ incorporated into the survey made it easier to identify.

Theme 3: limitations of using PROs in clinical practice

While the majority of clinicians found EPIC-26 data to be useful, some identified limitations in the information that they were able to obtain and use from this tool. Most concerns stemmed from how the information was summarized in the printed reports. A few clinicians felt that the data provided by EPIC was of limited value, and a single clinician felt that there was no utility in using EPIC whatsoever.

The most commonly expressed theme among clinicians was a criticism related to how the responses to the questionnaire were reported. There was a divided opinion in preference for having outcomes reported as grouped scores within a functional domain, versus reporting the individual responses for that domain. However, most clinicians would have liked more specific information on what was driving changes in the score trends.

C5: Having the full set of questions and responses available would be even more specific and detailed and would help to assess and identify the exact parameters that are changing for a patient.

C4: The trends are informative for identifying global changes in functioning and how a patient is generally doing. However, trends do not indicate what specific symptoms are changing for a patient. Knowing what questions were driving these changes would have been additionally helpful.

Some clinicians expressed strong views about the use of EPIC-26 in routine clinical practice because they felt that relevant patient information was elicited adequately during the clinical encounter and this process was duplicated by the EPIC-26 data collection process.

C10: Having the scores didn’t change what I asked a patient during review. I found myself still inquiring about the same anticipated side-effects in the manner that I normally would without EPIC.

C4: There is no substitute for a brief, but thorough history taken from the patient. Then you can take in their response, tone and context and put it all into perspective. I already capture information on bother.

Theme 4: additional clinical applications

In this pilot study, we chose to pilot EPIC-26 on prostate cancer patients undergoing active radiotherapy treatment. Most clinicians stated that the questionnaire could also be implemented in other clinical settings or for other non-clinical purposes.

Many clinicians felt that the patient profile that is captured by EPIC-26 would be useful for monitoring patients longitudinally once they have completed treatment. In particular, clinicians felt that side effects, like erectile dysfunction, represent long-term toxicity which may not manifest for several months after the completion of radiotherapy. Therefore, many clinicians were open to introducing EPIC-26 to patients who are transitioning to follow-up/cancer surveillance.

C4: If changes in scores on treatment stabilize after follow-up, we can ascertain the score changes were a result of acute side effects and that we don’t need to investigate symptoms further.

C6: I think the value in measuring erectile dysfunction matters more during the follow-up period than in the acute settings. Most of my patients begin to complain of changes in erectile function after several months and having this tool to capture and measure these changes would be very beneficial.

In addition to applications of EPIC in clinical practice, some clinicians felt that the use of EPIC-26 would be beneficial for collecting data on patient outcomes. Most felt that these data could be used to assess treatment targets, for quality assurance purposes, and for research/policy development.

C2: From a quality assurance perspective, it would be great to implement a questionnaire like this across several cancer-centers and see where we stand in terms of rates of toxicity and quality of life measures.

C4: Think about being able to correlate patient scores with toxicities and seeing what areas are commonly being affected for patients and to what degree. It can help guide policy development down the road within our institution for treatment guidelines.

Patients’ perceptions

Both favorable themes and expressed concerns arose from the open-ended patient interview comments. There were several comments of general support of implementing EPIC in clinical practice, and most patients welcomed the opportunity to report their prostate-specific symptoms systematically to the health-care team, feeling that this would assist in their evaluation and care. Some patients went so far as to suggest that a web-based version be available so that they could record their status from home.

Other comments from patients reflected potential barriers to the use of EPIC in practice. While general enthusiasm for reporting symptoms was observed, a few patients expressed concern about reporting their symptoms within the sexual domain. This was particularly so when the exercise was repeated weekly, and particularly for men who had limitations in sexual functioning that pre-dated their diagnosis and treatment, some of whom suggested at “not applicable” category should exist. Third, regarding the practical aspects of symptom evaluation, some patients made clear that they did not like touch-screen or mouse-controlled responses and that a paper version would be preferable. In addition, one patient expressed concern that the questionnaire could “replace” time with the clinicians, and one wanted an option to add comments. With regard to weekly patient assessments in radiotherapy review, many patients did not have a change of health status from week to week, prompting some to ask for a “no change” option for questions that they found to be redundant on a week-to-week basis.

Discussion

The aims of this pilot study were to evaluate the perceptions of clinician participants involved in using a prostate cancer-specific PRO assessment tool in clinical practice and to ensure patient acceptability of the process. The qualitative findings contribute evidence to support the routine use of PROs in clinical oncology practice. Our findings suggest that there was a general willingness and acceptance by clinicians to use EPIC-26 data in clinical practice. Clinician participants found the information from EPIC-26 to be generally informative and to add value to the clinical encounter. These findings are consistent with other findings relating to the use of PROs in general practice [18, 19].

The scientific literature on using PROs in clinical oncology is limited. With increasing survivorship for malignancies like prostate cancer, clinical guidelines have now been developed that incorporate provisions for managing long-term or late effects of cancer and their impacts on quality of life [20]. While EPIC-26 provides specific information on functional outcomes, it is unknown how these data can best inform clinical practice. Our findings suggest that these outcomes may facilitate communication and add efficiency to the encounter rather than impact on specific medical decision-making or immediate patient management.

There are several limitations to this study which affect the generalizability of the findings. The sample size was relatively small, and data saturation was not formally assessed. The participants also represented a very homogenous population of health-care providers who practice at a single cancer institution in Canada. Snyder’s paper on implementing PROs assessment in clinical practice suggests that there are many site-specific differences in workflow and local practice culture which influence how PROs are used in clinic [12]. Another study limitation was the fact that patient demographics such as preferred language and culture were not collected, so it is unknown how these may impact patients’ interpretations of questions. Further, the reference range scores were adopted from patient data obtained 6 months after prostate cancer treatment and this information may be less applicable to patients currently undergoing treatment [21]. Therefore, a set of reference scores should be established that reflect expected changes in PRO scores for patients at different stages in their treatment and follow-up. Plotting patient scores against these could be used for making informed managements decisions.

Despite these limitations, several recurrent themes emerged. Clinicians found that EPIC-26 was particularly valuable for improving communication during the patient encounter; this finding is consistent with data available from randomized trials [22, 23]. These findings were explained by an enhanced understanding of the patient experience and improved ability for discussing symptoms. Further studies are required to confirm these results. Our findings illustrating the general value of EPIC assessments and their potential to improve the quality of patient care in the prostate cancer setting provide justification for a larger implantation study in Ontario that is now underway in four participating regional cancer centers. These data will provide more detailed findings on patient feasibility issues and patient acceptance (using systematic quantitative data collection from patient participants) as well as further qualitative data from participating clinicians across a variety of clinical settings (surgical and radiation clinics, each in academic and community practices).

A second important finding was the diversity of opinion in how clinicians preferred EPIC-26 results to be reported. Some clinician participants stated that they would have preferred itemized reporting, while others stated a preference for grouped score reporting. This will potentially become a critical issue as more abbreviated revisions of EPIC are developed, e.g., the expanded prostate cancer index composite for clinical practice (EPIC-CP) [24], a validated questionnaire consisting of a condensed 16-item version of EPIC-26. Itemized scoring may be more appropriate for EPIC-CP data than for EPIC-26 data; future research in Ontario (as noted above) will examine the necessity and utility of graphical score reporting for this condensed version of EPIC.

Finally, several clinicians identified a role for using EPIC-26 in health services research. Since EPIC-26 provides a means to measure the incidence and prevalence of PROs over the long-term, this information could be used for developing quality assurance programs. It might also be possible to use trends in scores over time at regional cancer centers to identify when local treatment policies require review and to help establish goals for improving cancer services.

Conclusion

EPIC-26 is a validated instrument for measuring PROs following treatment for prostate cancer. We have shown for the first time that the administration of EPIC-26 is feasible at a clinical level and is generally accepted by health-care professionals. These preliminary findings suggest that EPIC-26 may improve the clinician-patient encounter and provide information relevant to informed clinical practice. The small size of this study limits the generalizability of its findings. The findings, however, support the ongoing assessment of the impact of utilizing patient-reported quality-of-life assessment tools in clinical practice and for health services research purposes.

References

Madan RA, Shah AA, Dahut WL (2013) Is it time to reevaluate definitive therapy in prostate cancer? J Natl Cancer Inst 105(10):683–685

Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Michalski J, Sandler HM, Northouse L, Hembroff L, Lin X, Greenfield TK, Litwin MS, Saigal CS (2008) Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. N Engl J Med 358(12):1250–1261

Resnick MJ, Koyama T, Fan K-H, Albertsen PC, Goodman M, Hamilton AS, Hoffman RM, Potosky AL, Stanford JL, Stroup AM (2013) Long-term functional outcomes after treatment for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 368(5):436–445

Litwin MS, Hays RD, Fink A, Ganz PA, Leake B, Leach GE, Brook RH (1995) Quality-of-life outcomes in men treated for localized prostate cancer. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association 273(2):129–135

Madalinska JB, Essink-Bot M-L, de Koning HJ, Kirkels WJ, van der Maas PJ, Schröder FH (2001) Health-related quality-of-life effects of radical prostatectomy and primary radiotherapy for screen-detected or clinically diagnosed localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 19(6):1619–1628

Detmar SB, Muller MJ, Schornagel JH, Wever LD, Aaronson NK (2002) Health-related quality-of-life assessments and patient-physician communication. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association 288(23):3027–3034

Velikova G, Booth L, Smith AB, Brown PM, Lynch P, Brown JM, Selby PJ (2004) Measuring quality of life in routine oncology practice improves communication and patient well-being: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 22(4):714–724

Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, Silberman M, Yellen SB, Winicour P, Brannon J (1993) The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol 11(3):570–579

Barry MJ, Fowler Jr FJ, O’Leary MP, Bruskewitz R, Holtgrewe H, Mebust W, Cockett A (1992) The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. J Urol 148(5):1549–1557 discussion 1564

Wei JT, Dunn RL, Litwin MS, Sandler HM, Sanda MG (2000) Development and validation of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology 56(6):899–905

Szymanski KM, Wei JT, Dunn RL, Sanda MG (2010) Development and validation of an abbreviated version of the expanded prostate cancer index composite instrument for measuring health-related quality of life among prostate cancer survivors. Urology 76(5):1245–1250

Aaronson NK, Snyder C (2008) Using patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice: proceedings of an International Society of Quality of Life Research conference. Qual Life Res 17(10):1295–1295

Feldman-Stewart D, Brundage M (2009) A conceptual framework for patient–provider communication: a tool in the PRO research tool box. Qual Life Res 18(1):109–114

CCO (2013) Ontario Cancer Symptom Management Collaborative. https://www.cancercare.on.ca/ocs/qpi/ocsmc/. Accessed Nov 8 2013 2013

Chang VT, Hwang SS, Feuerman M (2000) Validation of the Edmonton symptom assessment scale. Cancer 88(9):2164–2171

Krueger RA (2009) Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research. Sage

Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N (2000) Qualitative research in health care: analysing qualitative data. BMJ: British Medical Journal 320(7227):114

Greenhalgh J, Meadows K (1999) The effectiveness of the use of patient-based measures of health in routine practice in improving the process and outcomes of patient care: a literature review. J Eval Clin Pract 5(4):401–416

Skevington SM, Day R, Chisholm A, Trueman P (2005) How much do doctors use quality of life information in primary care? Testing the trans-theoretical model of behaviour change. Qual Life Res 14(4):911–922

NCCN (2013) Survivorship. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology Version 1.2013

Sanda MGDR, Michalski J, Sandler HM, Northouse L, Hembroff L, Lin X, Greenfield TK, Litwin MS, Saigal CS, Mahadevan A, Klein E, Kibel A, Pisters LL, Kuban D, Kaplan I, Wood D, Ciezki J, Shah N, Wei JT (2008) Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. N Engl J Med 358(12):1250

Detmar SBMM, Schornagel JH, Wever LDV, Aaronson NK (2002) Health-related quality-of-life assessments and patient-physician communication: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 288:3027–3034

Santana M-J, Feeny D, Johnson JA, McAlister FA, Kim D, Weinkauf J, Lien DC (2010) Assessing the use of health-related quality of life measures in the routine clinical care of lung-transplant patients. Qual Life Res 19(3):371–379

Chang P, Szymanski KM, Dunn RL, Chipman JJ, Litwin MS, Nguyen PL, Sweeney CJ, Cook R, Wagner AA, DeWolf WC (2011) Expanded prostate cancer index composite for clinical practice: development and validation of a practical health related quality of life instrument for use in the routine clinical care of patients with prostate cancer. J Urol 186(3):865–872

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the patients and their families who kindly volunteered their time to participate. They are also grateful to the Administration at Cancer Centre of Southeastern Ontario and the Radiotherapy Oncology Program for their support of the project.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest. Authors have full control of all primary data and agree to allow the journal to review their data if requested.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Korzeniowski, M., Kalyvas, M., Mahmud, A. et al. Piloting prostate cancer patient-reported outcomesin clinical practice. Support Care Cancer 24, 1983–1990 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2949-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2949-5