Abstract

Purpose

Radiochemotherapy is the standard of care for the treatment of anal carcinoma achieving good loco-regional control and sphincter preservation. This approach is however associated with acute and late toxicities including haematological, skin, bowel function and genito-urinary complications. This paper systematically reviews studies addressing the quality of life (QoL) implications of anal cancer and radiochemotherapy. The paper also evaluates how QoL is assessed in anal cancer.

Methods

Medline, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycInfo, Web of Science and the Cochrane Library were searched for publications (1996–2014) reporting the effects on patients of anal cancer and radiochemotherapy.

Results

Of the 152 papers reporting treatment-related effects on patients, only 11 provided a formal assessment of QoL. In the absence of an anal cancer-specific measure, QoL was assessed using generic cancer instruments such as the core EORTC quality of life questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) or colorectal cancer tools such as the EORTC QLQ-CR29. Bowel function, particularly diarrhoea, and sexual problems were the most commonly reported QoL concerns. The review of QoL issues of anal cancer patients treated with radiochemotherapy is limited by the QoL assessment measures used. It is argued that certain treatment-related toxicities, for example skin-induced radiation problems, are overlooked or inadequately represented in existing measures.

Conclusions

This review emphasises the need to develop an anal cancer-specific QoL measure and to incorporate QoL as an outcome of future trials in anal cancer. The results of this review are informative to clinicians and patients in terms of treatment decision-making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Background

Anal carcinoma is an uncommon malignancy accounting for 2 % of all gastrointestinal malignancies and 10 % of all anorectal malignancies but with increasing incidence over the past 25 years and higher incidence seen in women [1, 2]. Historically, anal cancer was regarded as a surgical disease treated by local excision or abdominoperineal resection (APR) with radiotherapy reserved for salvage or palliation. The landmark report of three cases by Nigro in 1974 [3] demonstrated complete responses after low-dose radiotherapy combined with mitomycin-C (MMC) and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) without surgical intervention. Subsequent trials [4–6] showcased the superiority of this treatment regimen over radiotherapy alone or radiotherapy with only 5-FU using different endpoints such as local control, recurrence-free survival, progression-free survival, colostomy-free survival or overall survival and thus radiotherapy with MMC and 5FU became the standard of care. Follow-up phase III trials failed to demonstrate benefits of alternative treatment schedules such as replacing MMC with cisplatin [7–9]. Five-year disease-free survival rates are reported as approximately 65 % [8].

This approach has improved loco-regional control with the majority of patients benefiting from sphincter preservation; however, clinician-reported acute grade 3 or 4 toxicities can be as high as 80 % [10] with severe late effects recorded in about 10 % patients [8]. Radiation dose has been identified as one of the most significant factors influencing adverse late effects [11]. Thus, alternative radiation treatment schedules tailored to reduce toxicities without compromise of disease control have been investigated, including the delivery of lower dose radiotherapy [12], continuous vs. split course treatments [13], brachytherapy [14] and the introduction of intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) as an alternative to the conventional conformal radiation therapy (CRT) [15, 16]. The current clinical practice guidelines for anal cancer recommend radiation doses of at least 45–50 Gray (Gy) with boost doses between 15 and 20 Gy, thus the study and management of late toxicities is clearly pertinent [11]. Toxicities can result in unintended treatment breaks and radiation dose reduction, leading to unfavourable disease-related outcomes as well as impacting on quality of life (QoL). Although toxicities have been extensively described using objective indices, little has been written using patient-reported outcome measures on the effect of toxicities on health-related QoL of radiochemotherapy for anal cancer.

QoL is a multi-dimensional construct shaped by physical health, psychological state, level of independence, social relationships, personal beliefs and their relationship to important features of their environment [17]. While a patient’s physical health, including symptoms experienced as a result of disease and treatment, impacts on QoL judgements, the patient’s response in terms of coping strategies, goals and expectations from treatment significantly affects their perception of QoL [18]. Therefore, assumptions regarding QoL cannot be made from an inspection of toxicity grades; only the patient can provide an accurate estimate of QoL [19].

Assessment of QoL is well established in rectal cancer with a repertoire of measures specifically tailored to the concerns of this patient group, such as the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer EORTC Colorectal Cancer Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-CR29) [20] and the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Colorectal (FACT-C) [21]. However, toxicities for anal cancer patients are likely to differ from rectal cancer given their different treatment modalities and the specific needs of anal cancer patients have not been well studied.

The current paper aims to review the published literature to clarify the QoL issues reported by patients with anal cancer undergoing radiochemotherapy. We also provide an overview of the effect of acute and chronic toxicities resulting from anal cancer and its treatment on QoL.

Methods

The protocol for this systematic review was informed by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination Guidance for undertaking reviews in health care [22] and the reporting follows the Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [23]. The protocol is available from the authors.

Search strategy and criteria for considering studies

Our search for publications reporting patients treated with radiochemotherapy for anal cancer extended from January 1996 to March 2014. Medline, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycInfo, Web of Science and the Cochrane Library Databases were searched. The search process was verified by a medical librarian. Anal cancer and its synonyms were entered as search terms combined with terms relating to treatment as well as the general terms of QoL and its variants using Boolean logic rules (Table 1). We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs), prospective trials, reviews of cohorts of patients, meta-analyses and reviews documenting QoL issues or toxicities following radiotherapy (CRT, IMRT, brachytherapy) and chemotherapy (5-FU, MMC, CDDP, capecitabine). Reports of conference proceedings, abstracts and case reports were excluded. Publications including anal cancer patients alongside other patient groups as well as those treated by surgery alone were also excluded.

Using these criteria, papers were selected for review based on titles and abstracts. SS screened all papers while KT and KD each independently reviewed half the records. Papers selected by either reviewer were included.

Methods of evaluation and data extraction

SS read the full-text version of selected papers and extracted the relevant data onto a data extraction form. For each publication that provided first-hand data on the effects on patients of anal cancer and its treatment, a record was made of the type of study, outcome measures and QoL or toxicity data. We noted all toxicities (acute and late), complications, adverse events or QoL. The data extraction forms were verified by an independent reviewer (KD). This review is primarily concerned with papers reporting QoL as an outcome using formal methods, specifically patient-reported outcome measures. Reviews, reports and meta-analyses were considered for descriptive and cross-referencing purposes but not for data extraction to avoid duplication. We recorded the quality of QoL reporting, QoL measures used, QoL issues reported and factors identified as impacting on QoL. A descriptive synthesis of the data was used because of the heterogeneity of studies in terms of research focus, treatments assessed, measures used and time of assessment. The quality of reporting QoL outcomes was assessed using a modified version of the checklist developed by Efficace and colleagues [24].

Results

Literature search

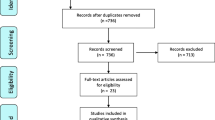

The selection process generated 1063 hits (Fig. 1). Screening identified 307 (29 %) papers for review with agreement between reviewers for 886 (83 %) papers. Altogether, 114 papers were subsequently rejected on the basis of subject matter (providing no account of the effects of anal cancer and its treatment n = 75), disease area (inclusion of patients without a diagnosis of anal cancer n = 15) or type of publication (reports of single cases n = 24). Thus, 193 papers were eligible for data extraction, of which, 36 were reviews, 4 reports/management guidelines and 1 provided a meta-analysis. Primary source data were provided by 152 publications, of which, 123 (81 %) were case series, typically retrospective in nature and 29 (19 %) described trials either of quasi-experimental design or RCTs. Sixteen papers reported the experiences of HIV-positive patients.

Overview of toxicities

Toxicities are presented here to give context. This section is descriptive and brief as the overall focus of the paper is on QoL. Toxicities were an outcome measure in 147 papers. Toxicities were graded by clinicians according to the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTAE) [25] (n = 49 papers), criteria outlined by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG)/EORTC Morbidity Scoring System [26] (n = 46), the Late Effects in Normal Tissues—Subjective Objective Management and Analytic (LENT-SOMA) Scales [27] (n = 15) and the World Health Organization (WHO) Morbidity Scoring System [28] (n = 8). For 43 studies, a toxicity grading system was not identified or formally used.

Haematological complications such as neutropenia and leukopenia were prevalent and were often described as severe and dose-limiting especially in patients treated with MMC and CDDP [8]. Skin reactions (radiation dermatitis and moist desquamation) were reported in almost all studies and were frequent; grade 3 or 4 acute skin toxicity was seen in 83 % of patients reviewed by Provencher et al. [29]. Other significant toxicities include pain, fatigue, genito-urinary complications, diarrhoea, incontinence and bone injury with the latter three recognised as common late complications [30–32]. Sexual functioning issues were not always assessed and were thus less commonly documented by clinicians. However, symptoms such as erectile dysfunction [33] and painful sexual intercourse [34] were significant late complications.

Quality assessment of QoL reporting

Of the 152 studies reviewed, 11 (7 %) used patient-reported tools to assess QoL associated with anal cancer and its treatment, which, for all patients involved chemotherapy and radiotherapy without surgery. No distinction was made between treatment-related and disease-related QoL issues. The first UK Anal Cancer Trial assessed QoL prospectively but was only published as a conference abstract [35]. This review focuses on the 11 studies published as full texts and these are outlined in Table 2. All studies except one adopted a cross-sectional design involving previously treated patients. Baseline QoL data were provided in one study that compared QoL of a sub-group of 199 patients at baseline and 2 months after treatment as part of the ACCORD 03 trial [36]. Six of the studies assessed QoL in the context of known group comparisons, for example according to age, sex, employment and marital status, treatment type and disease parameters [34, 36–41]. Comparisons were also made using reference values from published normative data from the general population or other disease groups [37, 38, 40–43] while two studies included matched healthy volunteers [42, 44]. QoL was a primary end point for 9 studies and for 8 of these studies, data on long-term QoL issues were provided with intervals between treatment and assessment varying from 2 years [38] to more than 12 years [40, 44]. The prevalence of missing data (where reported) ranged from 32 to 40 % [29, 38].

Scores on the modified Efficace checklist ranged from 5 to 10, with a mean (standard deviation) score of 8.7 (1.7). Efficace and colleagues [24] recommend a score of at least 8 as a general indicator of high quality; only 2 (18 %) studies did not satisfy this standard. Only 7 (64 %) studies provided a rationale for their choice of measurement. In addition, Efficace et al. [24] identify the documentation of missing data as one of the high-priority concerns and only 2 (18 %) studies satisfied this criterion.

QoL measures used

No anal cancer-specific QoL measure was identified and no qualitative studies assessing QoL issues relevant to anal cancer patients were detected. QoL issues were captured using multi-dimensional generic tools designed to be appropriate for all cancer types such as the EORTC QLQ-C30 [45] (n = 7 studies) [29, 36, 37, 39, 41, 42, 44], disease-specific measures designed and validated for use with a specific patient group such as colorectal cancer patients (EORTC QLQ-CR38/CR29 [20, 46] (n = 6) [29, 37, 39, 41, 42, 44] and the FACT-C [21] (n = 2) [34, 38]) or more broadly relating to gastro-intestinal disease such as the Gastro-intestinal Quality of Life Index (GIQLI) [47] (n = 2) [40, 43], and symptom-specific measures such as the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Sexual function scale [48] (n = 1) [38] and the Anal Sphincter-Conservative Treatment Questionnaire (AS-CT) [49] (n = 1) [36].

QoL issues

For 6 studies, overall or global QoL was summarised as acceptable and similar to normative data [29, 34, 37, 40, 41, 43] with mean EORTC QLQ-C30 global QoL scores ranging between 60.4 [41] and 85.9 [39] (100 represents the best possible score), median FACT-C total scores (out of 136) ranging between 110 [34] and 108 [38] and mean GIQLI scores (out of 144) between 117 [43] and 114 [40].

Table 3 outlines the QoL issues identified by the studies. Symptom-related data replicate the findings from toxicity reports although bowel functioning issues, in particular diarrhoea, and sexual problems were the most commonly reported issues in the QoL literature and were presented as significant concerns in seven studies [29, 34, 37, 38, 41, 42, 44]. Allal et al. [37] reported a threefold increase in diarrhoea in their cohort compared with population norms while 31 % of patients assessed by Das et al. [38] experienced diarrhoea “quite a bit” or “very much”. Das and colleagues also provided an assessment of sexual issues including declined sexual interest (reported in 65 % patients) reduced enjoyment of sex (71 %), difficulties getting aroused (72 %), erectile dysfunction (67 % of men who responded) and difficulties achieving orgasm (70 % of women who responded) [38]. Comparisons between anal cancer patients and population norms have also highlighted difficulties in social and role functioning [41, 42, 44], as well as sexual [37, 44, 42], physical [44], cognitive [41] and emotional function [41, 44] (Table 3).

Only one of the studies offered comparisons of QoL over time using a repeated measures design [36] and indicated improvement in QoL 2 months following treatment, especially in global QoL, emotional function and symptom scores including insomnia, constipation, appetite loss and pain. Other studies have also observed improved QoL over time inferred from comparisons of patients at different follow-up points [34] [36]. By contrast, Welzel et al. reported poorer physical functioning with longer follow-up [41].

Factors influencing QoL scores

Welzel et al. [41] addressed patient and disease-related factors related to QoL and found that fatigue was the only variable to have a significant impact on QoL. Toxicities including late complications and anal dysfunction have also been identified as important factors [34, 37, 38]. Other studies have uncovered associations between QoL and patient-related factors such as age; while Allal and colleagues [37] found that older patients had lower physical subscale scores, Das et al. [38] identified an opposite trend with lower QoL scores in patients under 51 years old. Das et al. also found that patients with a history of depression or anxiety or other cancers had a tendency to score lower on the physical subscale of the FACT-C. Patients who attained a more advanced level of education reported higher QoL scores in one study [34].

Assessment of the impact of treatment-related variables on QoL is limited given the small number of studies offering treatment comparisons, however Tournier-Rangeard and colleagues [36] found no short-term impact of treatment schedule on the evolution of QoL scores from baseline to 2 months after treatment. The findings of other cross-sectional studies support this observation [37, 39].

Discussion

This review has found relatively few studies reporting QoL issues of patients undergoing radiochemotherapy for anal cancer with formal QoL assessment largely absent from RCTs. Of the 307 studies reviewed, only 11 (4 %) studies included QoL as an outcome assessment and these were predominantly small scale questionnaire-based cross-sectional case reviews. There is no QoL questionnaire specific to anal cancer, which might explain the paucity of QoL research in this field. There is an abundance of reports of toxicities associated with anal cancer and its treatments, often measured with objective indices. The impact of these toxicities on QoL is acknowledged as an important outcome guiding decisions regarding treatment choices [34, 38]. Indeed, achieving a good quality of life alongside loco-regional control and the avoidance of a permanent stoma are identified within clinical practice guidelines as the primary aim of anal cancer treatment [11].

Consideration of QoL issues involves subjective evaluations and researchers use patient-reported outcome measures to quantify this qualitative information. However, some studies claiming to demonstrate a QoL impact of anal cancer treatment have done so with inappropriate QoL measures, for example one comparison of QoL following radiochemotherapy and surgery was based on data extracted from medical records [50] which will give a very incomplete assessment. Generic cancer QoL measures such as the EORTC QLQ-C30 are designed to capture issues relevant to all cancer types but are insensitive to unique disease-related features. Cancer site-specific tools thus complement these generic measures. In the absence of an anal cancer-specific QoL measure, colorectal cancer-specific QoL tools such as the EORTC QLQ-CR38/29 and FACT-C have been used. The studies included in this review all provided formal QoL assessments (although they were obtained with inappropriate instruments) and they had favourable quality assessment scores using the Efficace checklist [24]. They offer a useful insight into the QoL concerns of anal cancer patients.

The literature on toxicities provides numerous examples of complications associated with anal cancer and its treatments yet these are not necessarily translated into poor overall QoL evaluations. Several reports of anal cancer patients show similar QoL scores to population norms [29, 34, 37, 40, 41, 43]. Allal et al. [37] also identified disparities between objective and subjective parameters in relation to anorectal function and satisfaction. It has been proposed that over time, patients adapt to their changing health status and change their personal reference values regarding QoL [18]. Vordermark and colleagues [40] speculate that satisfaction with the apparent cure of malignant disease may also account for elevated QoL scores amongst anal cancer patients. However, there is evidence to suggest that patients with poorer health status, including more severe late complications and poorer anal function, report lower QoL scores [34, 37, 40, 41]. In addition, bowel and sexual function issues were flagged as particularly significant QoL concerns for anal cancer patients in a number of studies [29, 37, 38, 41, 42, 44].

The colorectal cancer-specific measures used in the studies reviewed were designed to include all relevant and specific issues relating to colorectal cancer. Although there is some overlap in the symptom and toxicity profiles of colorectal and anal cancer, there are several important differences. Thus, certain issues affecting anal cancer are inadequately covered by the generic or the colorectal instruments. Our review highlighted skin reactions such as radiation dermatitis and desquamation as a very common toxicity. Associated pain or soreness caused by skin reactions might be captured by the CR29 items measuring sore skin around the anal area or stoma and the FACT-C measuring pain or the general side effects of treatment, but these do not provide an adequate assessment of the more wide ranging impact of this issue for example on walking, sitting or inability to sleep due to pain. Sexual dysfunction was identified in a number of studies as an important QoL concern and although this was under-reported in the toxicity literature, in the QoL studies, patients were given the opportunity to rate the impact of sexual difficulties. The CR29 asks about interest in sex, impotence and dyspareunia while satisfaction with sex life is measured by the FACT-C. Issues relating to sexual dysfunction might however extend beyond those assessed using these measures, for example to include the impact of vaginal symptoms such as dryness and stenosis which were identified as having a negative impact on QoL by a third of female patients in Fakhrian et al.’s study [34]. In the QoL literature, bowel function issues such as diarrhoea and incontinence were also prevalent and again the CR29 and FACT-C might be regarded as inadequate to assess the full effect on QoL of such distressing symptoms.

One of the main limitations of this review is that the QoL concerns presented in this paper are confined to the content of questions asked of patients. A number of significant issues such as radiation-induced skin problems are likely to be under-reported. None of the studies reviewed were qualitative in design or provided patients with an opportunity to rate aspects of their disease or treatment not covered by the questionnaires. The studies reviewed were mostly cross-sectional and included only small numbers of patients, probably as a result of the rarity of anal cancer. Caution is therefore required before making generalisations about the QoL concerns of this patient group. The issue of non-responders and missing data, in particular with respect to the personal and potentially embarrassing issues of sexual dysfunction, presents a significant challenge. There is limited information about non-responders, thus generalisations from data collected from a small subset of patients who may be more motivated and successfully treated are likely to be unreliable.

This review is also limited in terms of its synthesis of data. The heterogeneous nature of the studies reviewed, for example whether QoL was the primary outcome, the measures used and follow-up assessment times, resulted in data being presented in different formats; comparisons between studies were difficult and we were not in a position to present prevalence figures for individual QoL issues. In addition, the absence of baseline QoL data in all but one study [36] makes it difficult to assess the impact of treatment on QoL.

To our knowledge, this review represents the first attempt to systematically review studies where QoL has been formally assessed in anal cancer patients. Despite the limitations of these studies, they can be applauded for their high standard of method reporting and for using validated QoL measures. The review has highlighted the wide ranging and long-lasting QoL issues (bowel function, including diarrhoea, and sexual function) facing anal cancer patients treated with radiochemotherapy. We have also identified a need for a site-specific instrument for anal cancer, to allow all specific and relevant QoL concerns to be assessed. It is particularly important to include such an instrument in the design of randomised clinical trials, to ensure complete and prospective assessment of the impact of treatment on QoL. Documentation of late effects and QoL assessment is recommended within the anal cancer clinical practice guidelines [11]. The results of this review are informative to clinicians in their design of future trials and can support their consultations with patients about the potential impact of treatment on quality of life thus allowing patients to make informed treatment decisions in light of their own preferences and values and attitudes to risk. The issues identified from this review will be considered in the development of a new anal cancer module to supplement the EORTC QLQ-C30 which will be sensitive to the acute and long-term issues facing patients treated with radiochemotherapy.

References

Aggarwal A, Duke S, Glynne-Jones R (2013) Anal cancer: are we making progress? Curr Oncol Rep 15(2):170–181. doi:10.1007/s11912-013-0296-6

Jemal ASE, Dorell C et al (2013) Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2009, featuring the burden and trends in human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated cancers and HPV vaccination coverage levels. J Natl Cancer Inst 105:175–201

Nigro NDVV, Considine B Jr (1974) Combined therapy for cancer of the anal canal: a preliminary report. Dis Colon Rectum 17:354–356

UKCCCR Anal Cancer Working Party (1996) Epidermoid anal cancer: results from the UKCCCR randomised trial of radiotherapy alone versus radiotherapy, 5-fluorouracil and mitomycin. Lancet 348:1049–1054

Flam M, John M, Pajak TF, Petrelli N, Myerson R, Doggett S, Quivey J, Rotman M, Kerman H, Coia L, Murray K (1996) Role of mitomycin in combination with fluorouracil and radiotherapy, and of salvage chemoradiation in the definitive nonsurgical treatment of epidermoid carcinoma of the anal canal: results of a phase III randomized intergroup study. J Clin Oncol 14(9):2527–2539

Bartelink H, Roelofsen F, Eschwege F, Rougier P, Bosset JF, Gonzalez DG, Peiffert D, van Glabbeke M, Pierart M (1997) Concomitant radiotherapy and chemotherapy is superior to radiotherapy alone in the treatment of locally advanced anal cancer: results of a phase III randomized trial of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Radiotherapy and Gastrointestinal Cooperative Groups. J Clin Oncol 15(5):2040–2049

James RD, Glynne-Jones R, Meadows HM, Cunningham D, Myint AS, Saunders MP, Maughan T, McDonald A, Essapen S, Leslie M, Falk S, Wilson C, Gollins S, Begum R, Ledermann J, Kadalayil L, Sebag-Montefiore D (2013) Mitomycin or cisplatin chemoradiation with or without maintenance chemotherapy for treatment of squamous-cell carcinoma of the anus (ACT II): a randomised, phase 3, open-label, 2x2 factorial trial. Lancet Oncol 14(6):516–524. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(13)70086-x

Ajani JA, Winter KA, Gunderson LL, Pedersen J, Benson AB 3rd, Thomas CR Jr, Mayer RJ, Haddock MG, Rich TA, Willett C (2008) Fluorouracil, mitomycin, and radiotherapy vs fluorouracil, cisplatin, and radiotherapy for carcinoma of the anal canal: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 299(16):1914–1921. doi:10.1001/jama.299.16.1914

Peiffert D, Tournier-Rangeard L, Gerard JP, Lemanski C, Francois E, Giovannini M, Cvitkovic F, Mirabel X, Bouche O, Luporsi E, Conroy T, Montoto-Grillot C, Mornex F, Lusinchi A, Hannoun-Levi JM, Seitz JF, Adenis A, Hennequin C, Denis B, Ducreux M (2012) Induction chemotherapy and dose intensification of the radiation boost in locally advanced anal canal carcinoma: final analysis of the randomized UNICANCER ACCORD 03 trial. J Clin Oncol 30(16):1941–1948. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.35.4837

Ajani JA, Wang XM, Izzo JG, Crane CH, Eng C, Skibber JM, Das P, Rashid A (2010) Molecular biomarkers correlate with disease-free survival in patients with anal canal carcinoma treated with chemoradiation. Dig Dis Sci 55(4):1098–1105. doi:10.1007/s10620-009-0812-6

Glynne-Jones R, Nilsson PJ, Aschele C, Goh V, Peiffert D, Cervantes A, Arnold D, ESMO, ESSO, ESTRO (2014) Anal cancer: ESMO-ESSO-ESTRO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Radiother Oncol 111(3):330–339

Allal AS, Mermillod B, Roth AD, Marti MC, Kurtz JM (1997) Impact of clinical and therapeutic factors on major late complications after radiotherapy with or without concomitant chemotherapy for anal carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 39(5):1099–1105

Glynne-Jones R, Sebag-Montefiore D, Adams R, McDonald A, Gollins S, James R, Northover JMA, Meadows HM, Jitlal M, Par UACTW (2011) “Mind the Gap”—the impact of variations in the duration of the treatment gap and overall treatment time in the first UK Anal Cancer Trial (ACT I). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 81(5):1488–1494. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.07.1995

Gerard JP, Mauro F, Thomas L, Castelain B, Mazeron JJ, Ardiet JM, Peiffert D (1999) Treatment of squamous cell anal canal carcinoma with pulsed dose rate brachytherapy. Feasibility study of a French cooperative group. Radiother Oncol 51(2):129–131

Pepek JM, Willett CG, Wu QJ, Yoo S, Clough RW, Czito BG (2010) Intensity-modulated radiation therapy for anal malignancies: a preliminary toxicity and disease outcomes analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 78(5):1413–1419. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.09.046

Kachnic LA, Winter K, Myerson RJ, Goodyear MD, Willins J, Esthappan J, Haddock MG, Rotman M, Parikh PJ, Safran H, Willett CG (2013) RTOG 0529: a phase 2 evaluation of dose-painted intensity modulated radiation therapy in combination with 5-fluorouracil and mitomycin-C for the reduction of acute morbidity in carcinoma of the anal canal. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 86(1):27–33. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.09.023

Harper A, Power M, Grp W (1998) Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol Med 28(3):551–558

Sprangers MASC (1999) Integrating response shift into health-related quality of life research: a theoretical model. Soc Sci Med 48(11):1507–1515

Fayers P, Machin D (2013) Quality of life. The assessment, analysis and interpretation of patient-reported outcomes. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester

Sprangers MAG, Velde AT, Aaronson NK (1999) The construction and testing of the EORTC colorectal cancer-specific quality of life questionnaire module (QLQ-CR38). Eur J Cancer 35(2):238–247

Ward RL, Hahn EA, Mo F, Hernandez L, Tulsky DS, Cella D (1999) Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Colorectal (FACT-C) quality of life instrument. Qual Life Res 8(3):181–195

Dissemination CfRa. Systematic reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. [Internet]

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D, The PG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement

Efficace FBA, Osoba D, Gotay C, Flechtner H, D’haese S, Zurlo A (2003) Beyond the development of health-related quality-of-life (HRQOL) measures: a checklist for evaluating HRQOL outcomes in cancer clinical trials—does HRQOL evaluation in prostate cancer research inform clinical decision making? J Clin Oncol 21(18):3502–3511

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Files. http://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/About.html

Cox JFSJ, Pajak TF (1995) Toxicity criteria of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 31:1341–1346

(1995) LENT-SOMA scales for all anatomic sites. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 31:1049–1091

WHO handbook for reporting results of cancer treatment. (World Health Organization. 1979). World Health Organization, Geneva

Provencher S, Oehler C, Lavertu S, Jolicoeur M, Fortin B, Donath D (2010) Quality of life and tumor control after short split-course chemoradiation for anal canal carcinoma. Radiat Oncol 5:41. doi:10.1186/1748-717X-5-41

John M, Flam M, Palma N (1996) Ten-year results of chemoradiation for anal cancer: focus on late morbidity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 34(1):65–69

Young SC, Solomon MJ, Hruby G, Frizelle FA (2009) Review of 120 anal cancer patients. Color Dis 11(9):909–914. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01723.x

Dwyer MK, Gebski VJ, Jayamohan J (2006) The bottom line: outcomes after conservation treatment in anal cancer. Australas Radiol 50(1):46–51

Wexler A, Berson AM, Goldstone SE, Waltzman R, Penzer J, Maisonet OG, McDermott B, Rescigno J (2008) Invasive anal squamous-cell carcinoma in the HIV-positive patient: outcome in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Dis Colon Rectum 51(1):73–81

Fakhrian K, Sauer T, Dinkel A, Klemm S, Schuster T, Molls M, Geinitz H (2013) Chronic adverse events and quality of life after radiochemotherapy in anal cancer patients. A single institution experience and review of the literature. Strahlenther Onkol 189(6):486–494. doi:10.1007/s00066-013-0314-5

Slevin MLPPN RC, Meadows HM, et al. on behalf of the UKCCCR Anal Cancer Trial Working Party (1998) Chemotherapy for anal cancer improves quality of life compared to radiotherapy alone [abstract]. In: American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting

Tournier-Rangeard L, Mercier M, Peiffert D, Gerard J-P, Romestaing P, Lemanski C, Mirabel X, Pommier P, Denis B (2008) Radiochemotherapy of locally advanced anal canal carcinoma: prospective assessment of early impact on the quality of life (randomized trial ACCORD 03). Radiother Oncol 87(3):391–397. doi:10.1016/j.radonc.2007.12.004

Allal AS, Sprangers MA, Laurencet F, Reymond MA, Kurtz JM (1999) Assessment of long-term quality of life in patients with anal carcinomas treated by radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy. Br J Cancer 80(10):1588–1594

Das P, Cantor SB, Parker CL, Zampieri JB, Baschnagel A, Eng C, Delclos ME, Krishnan S, Janjan NA, Crane CH (2010) Long-term quality of life after radiotherapy for the treatment of anal cancer. Cancer 116(4):822–829. doi:10.1002/cncr.24906

Oehler-Janne C, Seifert B, Lutolf UM, Studer G, Glanzmann C, Ciernik IF (2007) Clinical outcome after treatment with a brachytherapy boost versus external beam boost for anal carcinoma. Brachytherapy 6(3):218–226

Vordermark D, Sailer M, Flentje M, Thiede A, Kolbl O (1999) Curative-intent radiation therapy in anal carcinoma: quality of life and sphincter function. Radiother Oncol 52(3):239–243

Welzel G, Hagele V, Wenz F, Mai SK (2011) Quality of life outcomes in patients with anal cancer after combined radiochemotherapy. Strahlenther Onkol 187(3):175–182. doi:10.1007/s00066-010-2175-5

Bentzen AG, Balteskard L, Wanderas EH, Frykholm G, Wilsgaard T, Dahl O, Guren MG (2013) Impaired health-related quality of life after chemoradiotherapy for anal cancer: late effects in a national cohort of 128 survivors. Acta Oncol 52(4):736–744. doi:10.3109/0284186X.2013.770599

Vordermark D, Flentje M, Sailer M, Kolbl O (2001) Intracavitary afterloading boost in anal canal carcinoma. Results, function and quality of life. Strahlenther Onkol 177(5):252–258

Jephcott CR, Paltiel C, Hay J (2004) Quality of life after non-surgical treatment of anal carcinoma: a case control study of long-term survivors. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 16(8):530–535

Aaronson NKAS, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, de Haes JC et al (1993) The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 85(5):365–376

Whistance RN, Conroy T, Chie W, Costantini A, Sezer O, Koller M, Johnson CD, Pilkington SA, Arraras J, Ben-Josef E, Pullyblank AM, Fayers P, Blazeby JM, European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Group (2009) Clinical and psychometric validation of the EORTC QLQ-CR29 questionnaire module to assess health-related quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer 45(17):3017–3026

Eypasch EWJ, Wood-Dauphinee S, Ure BM, Schmuelling C, Neugebauer E, Troidl H (1995) Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index: development, validation and application of a new instrument. Br J Surg 82:216–222

Sherbourne CD (1992) Social functioning: sexual problems measures. Measuring functioning and well-being. Duke University Press, Durham

Bosset JF SS, Pelissier R, Mercier M, Mejat E, Mantion G (1993) Proposition of a specific quality of life scale for patients treated by conservative surgery for rectal cancer. In: First international symposium on conservative treatment in oncology. p 35

Chen Y-W, Yen S-H, Chen S-Y, Huang P-I, Shiau C-Y, Liu Y-M, Lin J-K, Wang L-W (2007) Anus-preservation treatment for anal cancer: retrospective analysis at a single institution. J Surg Oncol 96(5):374–380

Acknowledgments

This review was funded by the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life (EORTC QOL) Group as part of a project to develop a module to supplement the core instrument for assessment of HRQoL in patients with anal cancer.

We thank Paula Sands, Academic Liaison Librarian, University of Southampton, for her assistance during the search process.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest or competing financial interests. The authors have full control of the material presented and give permission to Supportive Care in Cancer to review the material if requested.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sodergren, S.C., Vassiliou, V., Dennis, K. et al. Systematic review of the quality of life issues associated with anal cancer and its treatment with radiochemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 23, 3613–3623 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2879-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2879-2