Abstract

Purpose

This study aims to identify the current practices of health professionals in the assessment and treatment of cancer-related fatigue (CRF).

Methods

Health professionals working with oncology clients participated in an electronic survey distributed via professional associations and oncology societies.

Results

One hundred twenty-nine professionals from nursing, medical, and allied health disciplines participated in an electronic survey. Overall, there was a perception that CRF was inadequately managed at some facilities. Routine fatigue screening processes in the workplace were reported by more than half of participants; however, less than one quarter used a clinical guideline or conducted in-depth CRF assessments. Awareness of interventions for CRF varied amongst participants with one quarter able to list five appropriate interventions for cancer-related fatigue. Access to services for managing fatigue was inconsistent across service types, with post-treatment triage a high priority for CRF in some organisations yet not others. Participants identified a need for improved guidelines, enhanced expertise and better access to services for people with CRF.

Conclusions

There is a need for further education in CRF management for a range of health disciplines in oncology and additional resources to facilitate translation of CRF guidelines into clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Fatigue is a common and debilitating symptom of cancer [1], and the assessment and management of cancer-related fatigue (CRF) is central to contemporary cancer care [2]. Research from several health disciplines has contributed to the current evidence-based guidelines for treating CRF, yet studies in the USA and Europe indicate guidelines may be inconsistently implemented [3–5]. While the body of evidence supporting interventions for CRF is growing, there has been limited research into how clinicians assess and treat CRF. An inter-professional approach using interventions tailored to individuals’ needs is arguably optimal [1]. On examination, current guidelines lack clarity surrounding the specific roles of different health care professionals involved in assessing or treating CRF, such as medical practitioners, nurses, occupational therapists, physiotherapists and psychologists. It is recommended that scope of practice for health professionals and clear referral pathways be locally defined for implementation of comprehensive care models for CRF [6]. This study seeks to identify current practice as well as barriers and solutions to optimal care for those with CRF.

The main purpose of this study was to explore clinical assessment and management of CRF to inform the design of comprehensive cancer care. The research questions for this study were—what do health practitioners know about CRF; how do they assess and treat CRF; and what are perceived barriers to optimal treatment?

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was developed to obtain data from Australian health professionals who worked with people with a cancer diagnosis in their practice. Using a Question Appraisal System methodology described by Willis [7], questions were drafted to gather data to answer the research questions including as few items as possible to encourage completion of the survey [8].

The survey was tested using cognitive interviews with five current or recently practising health professionals to increase rigour and reduce ambiguity in question and answer choices [7]. Cognitive interviews required participants to ‘think out loud’ about their responses, and the interviewer used probe questions to clarify thoughts. Post-graduate university students were recruited via posters and electronic mail. Several minor amendments were made following cognitive interviews with one nurse and four allied health professionals. The final survey, comprising 20 questions, was entered into Qualtrics® survey software to enable electronic distribution. For ease of completion and to obtain maximum data, the respondents were able to skip redundant items and add comments in the ‘other’ category for most questions. The question categories and number of items are listed below. See Appendix 1 for the survey.

Survey question categories

-

1.

Demographic details of the respondent: age, gender, professional discipline, years of experience and Australian state (five questions)

-

2.

Details relating to practice setting: type of facility/service, practice involving clients with cancer and referral management processes (five questions)

-

3.

Knowledge and practice relating to CRF: guideline use, proactive screening for CRF, screening or assessment tools, outcome measures and knowledge of interventions (eight questions)

-

4.

Barriers to practice: perceptions and suggestions to overcome barriers and facilitate CRF management (two questions)

To obtain a broad representation of health professional disciplines across Australia, eight national professional associations and oncology societies were approached to distribute the survey in routine electronic communications between January and April 2014. Six organisations distributed the survey: the Australian Physiotherapy Association, Cancer Nurses Society of Australia, Exercise and Sports Science Australia, Occupational Therapy Australia, Palliative Care Australia and Psycho-Oncology Cooperative Group. A link to the survey was also posted on the staff intranet of a specialist cancer hospital for 2 weeks. Health professionals who had practiced within the past 12 months and encountered people with cancer in their practice were eligible to participate. Consent to participate was implied by survey completion. Timely completion was encouraged by a one in five chances to receive a cinema ticket for the first 100 respondents. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from La Trobe University (Australia), Faculty of Health Sciences ethics committee (FHEC13/216).

Data analysis

Survey data were exported into Microsoft Excel® to enable data analysis. Due to the broad sample of cancer health professionals and small numbers within most disciplines, analysis was limited to descriptive statistics and tests of statistical significance were not performed. Sum, average and standard deviations were extracted as relevant to each question and percentages were calculated. Qualitative thematic analysis was applied to free-text data in the final two questions, because of its suitability for analysis of fragmented text [9]. Thematic analysis used open coding of data and categorisation of codes to develop themes as described by Elo and Kyngäs [10]. Codes were counted to determine frequency of similar views.

Results

Survey participants

Of the 129 participants who commenced the electronic survey, 112 completed the survey. Sixty-six allied health professionals, 44 nurses and ten medical practitioners participated. Others included a music therapist, a radiotherapist, a counsellor, two pastoral workers and three research or project officers. The average age of participants was 43.2 years, 94 % were female and their average years practising was 16.2 (range 1.5–50). Most participants practiced in a metropolitan location. Participants practiced in six Australian states or territories with most from Victoria. Table 1 summarises participant demographics.

Participants (n = 127) reported their clinical practice settings as acute hospital 40 %, community health 15 %, palliative care centre 14 % and private practice 9 %. A range of other practice settings was reported by 17 % of participants, including domiciliary and rehabilitation services. Thirty-nine per cent indicated that they worked in a specialist oncology setting.

Health professionals’ knowledge and expertise in cancer-related fatigue

Fifteen percent of the sample reported receiving specialist education on CRF. A further 68 % of participants had some knowledge of CRF, either through reading journal articles, undergraduate coursework, informal learning in the workplace or personal experience of CRF. Participants were asked to list up to five interventions for CRF, with 27 % able to name five interventions while 28 % listed none. Participants’ awareness of fatigue management strategies was focused to their discipline practice area. Occupational therapists listed the most CRF interventions. Significantly fewer participants in acute hospital settings listed three to five CRF interventions compared with participants in both specialist oncology and combined sub-acute/community-based settings (Chi-squared test, p < 0.04) (see Appendix 2A for data). However, years of practice did not influence the number of interventions listed (p < 0.05). Interventions listed by participants are shown in Table 2, classified by the research team and detailed in Appendix 2B. The category ‘other actions’ included referrals for services at home, team discussions and non-specific descriptions (e.g. ‘psychosocial’).

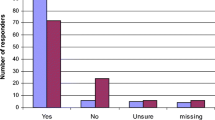

Expertise in CRF management was self-rated. More than half reported some expertise in CRF management. Figure 1 represents participants’ CRF knowledge, CRF expertise and frequency of contact with oncology clients. Participants reported that they personally implemented 80 % of the interventions for cancer-related fatigue that they listed.

Screening, assessment and monitoring of CRF

Clinical guidelines for the assessment and management of CRF were reportedly used in the health services of 27 (21 %) participants. The US National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines [1] were used in 11 % of services. National Cancer Action Team, European Association for Palliative Care and Exercise and Sports Science Australia guidelines were each used in one service. Three participants reported using facility-specific guidelines while guidelines developed by the disciplines of exercise physiology, medicine, nursing, occupational therapy or physiotherapy were reportedly used in the services of eight participants.

The practice of routine fatigue screening occurred in the organisations of 60 % of participants but did not significantly vary between different practice settings (p < 0.05) (see Appendix 2A for data). Almost one third of nurses reported that they asked their clients direct questions regarding CRF while 22 % of both doctors and other health professionals also directly asked clients about CRF. One third of participants reported that patient or family concern prompted screening. Informal interview was the most common method of screening or assessment in the workplaces of 61 % of participants, followed by observation (44 %). A standardised patient-reported outcome measure was used in one quarter of participant workplaces. Twenty-six allied health professionals, nine nurses and one doctor reported that functional assessment or exercise testing were conducted in their services. Only two respondents indicated that they used a CRF-specific assessment form.

Single-item scales were the most common methods used to monitor symptom changes, with 43 % of participants reporting the use of numeric rating scales and 11 % using visual analogue scales. Other patient-reported outcome measures such as quality of life questionnaires or the Brief Fatigue Inventory [11] were used to monitor fatigue in the organisations of 21 % of participants.

Access and service accessibility

Triage systems to determine priority access for new referrals were used in 70 % of participants’ services. Discipline priority systems were reportedly not used in the workplaces of 38 participants, particularly acute hospital and specialist oncology settings. To determine variations in access to services, participants were asked to apply their triage systems to a hypothetical case:

‘Brad’, a 54-year-old man who completed surgery and chemotherapy for cancer about 4 months ago, was considering work return. He was able to care for himself but unable to carry on normal activity or to do active work with an Australia-Modified Karnofsky Performance Status of 70 [12]. He identified his usual fatigue as 6/10.

Eighty-two per cent of participants reported that this type of referral would be received in their clinical settings. Where triage systems were used, ‘Brad’ was triaged as ‘low priority’ by 23 %, ‘medium’ by 51 % and ‘high’ by 15 % of participants. Fifteen participants noted other factors that could influence access to their service, such as cancer stage, treatment phase, lymphoedema or age. Brad would not have met the eligibility criteria in seven participants’ services either because he had completed treatment, was an outpatient, not palliative or ‘complex’, or ineligible cancer type/age. Table 3 shows the variation in facility triage guidelines in different practice settings.

Depending on the service, Brad would be offered his first appointment within 24 h to 12 months. Waiting times for clients triaged as ‘low’ priority varied between 5 days and 12 months (average 92 days), ‘medium’ between 1 and 84 days (average 28 days) and clients considered ‘urgent’ would be offered an appointment between 1 and 52 days (average 16 days). In the services of 22 participants without priority systems, half had a current waiting time of less than 2 weeks for a first appointment, while only three participants reported a wait time of more than 6 weeks. Sixteen participants did not provide an estimate of current waiting time.

Reassurance, screening, assessment and referral to other services were the most commonly offered services for clients such as Brad. In-depth fatigue assessment was reported by nearly one quarter of participants. Services offered to clients similar to Brad are presented in Table 4.

Barriers to optimal management of CRF

Many respondents (71 %) reported that CRF was inadequately managed by their service. The most commonly reported staff-related barrier was a ‘lack of awareness about possible interventions by referrers’, endorsed by 63 % of participants. Perceived lack of expertise in assessment or management (52 %), staff considering CRF a low priority (40 %), referrals not being made (37 %) and assuming that someone else was addressing CRF (27 %) were frequently reported. A social worker stated that ‘some staff avoid raising hopes of referral on and instead provide information only or normalise the problem’. Two nurses commented that some staff accepted CRF as ‘normal’ or ‘part and parcel of the illness’.

Half of the participants identified an absence of treatment guidelines and lack of routine screening for fatigue as barriers to optimal management, with lack of documentation relating to fatigue also frequently reported (47 %). Thirteen participants across seven disciplines perceived limited resources to be a barrier to CRF management, with CRF often deemed a low priority where there were competing demands on staff time. One nurse reported limited access to services in rural areas.

Qualitative thematic analysis [10] was applied to 52 free-text suggestions by participants for improving CRF management. Three main themes were identified, summarised in Table 5.

Thirteen participants proposed improved guidelines or defined referral pathways for managing CRF. Ten participants identified a need for valid assessment or screening tools, and eight participants suggested routine screening for fatigue. Increasing staff expertise in CRF management was strongly supported, with 17 participants suggesting better staff education about fatigue treatment, particularly in clinical settings. Five participants recognised that specialist skills pertaining to fatigue may exist in particular disciplines such as occupational therapy and physiotherapy. However, seven participants noted that providing optimal services for people with CRF requires adequate resourcing in specialist and sub-acute settings.

Discussion

Fatigue can be a prolonged and debilitating condition for survivors of cancer. Despite its high prevalence, the results of this study indicate that CRF may be under-recognised and under-treated. This may in part be associated with limited health professionals’ knowledge of assessment and the broader scope of possible interventions for CRF beyond a discipline’s practice area. Other international surveys of health professionals working in oncology have reported similar findings. Cancer physiotherapists in the UK most commonly promoted exercise and energy conservation [13], while Jordanian nurses believed anaemia correction, sleep, energy conservation and nutrition were the optimal strategies [14]. Oncology doctors and nurses in Turkey predominantly used pharmacological, educational and nutritional interventions [15]. Current evidence endorses a multifaceted approach [1], including symptom management [16], physical exercise [17, 18] and psychological strategies [19, 20].

International studies have identified a need for more health professional education relating to CRF [13–15, 21]. The most common CRF education received by participants in the current survey was self-directed. This form of learning has been described as a ‘hit and miss’ approach that may result in lack of confidence in one’s knowledge [13], and possibly prompted participants to request more staff education. A UK survey noted that most cancer physiotherapists gained their knowledge from self-directed learning [13], and a multinational survey found that conference presentations were the predominant form of education for paediatric cancer health professionals [21]. These findings support conclusions by other researchers that an inter-professional approach to CRF education may improve the quality of care for people with CRF [21].

The current study identified different triage and screening practices for CRF. Clinical guidelines and resources are argued to influence practice in health care systems [22, 23]. Few respondents used structured assessment tools or guidelines, consistent with other research findings [15, 21]. Availability and use of practical guidelines that have been adapted to local settings may result in more consistent practice [24] by assisting clinicians’ decision-making underpinned by the best available evidence [25]. However, a systematic review of guideline implementation strategies found that traditional non-interactive education appears to have limited effect on practice, and strategies such as interactive education and decision support systems are needed to increase guideline implementation [26].

Existing guidelines lack clarity as to the roles of different professionals in the management of CRF. Some authors consider that nurses can play key roles in educating patients, fatigue screening and developing systems for treatment of CRF [27] however specific roles need to be determined and articulated at a local level [6]. These findings further support a comprehensive and multidisciplinary approach to CRF management.

Barriers to CRF management have previously been classified as patient, provider and system barriers [4]. Several survey participants identified insufficient resources as a major barrier to routine screening and assessment for CRF, reflecting the need to prioritise services in an environment of increasing costs and demand for health care [28]. Resources are needed to adapt and implement practice guidelines; however, limited research has examined costs of implementing guidelines [26]. One study investigating outcomes of a CRF clinic reported that approximately 1.5 medical and nursing hours were required to evaluate, educate and plan treatment for people with moderate to severe CRF [29]. Further studies evaluating the cost of CRF guideline implementation are needed.

This study had a number of limitations. Although a broad range of health professionals who may work with people with cancer participated, some professional groups were under-represented. Low participation by doctors, social workers and dieticians may have occurred because the survey could not be distributed via their associations. Cancer nurses have a national society, but other professions lack a national oncology interest group. The sample of occupational therapists may not be representative of those across Australia because of professional development and survey promotion occurring within an active Victorian oncology interest group, which did not exist in other states. Further, potentially eligible participants such as community health or rehabilitation practitioners may not have considered that they met the survey inclusion criteria. While invitation through professional organisations of intended participants may have reduced selection bias, the unknown response rate limits generalisability of survey results [30]. The survey was distributed via email invitation and it is not known how many of the emails or attachments were opened or read by health professionals meeting the selection criteria [30]. It is also common for people overwhelmed by e-mail volume to adopt a practice of deletion if they are not interested in the topic [31]. While incentives for timely completion were offered, reminder e-mails were not sent which may have increased participation [31].

Conclusions

This study found inconsistencies in clinical assessment and management of fatigue in survivors of cancer amongst oncology health professionals. Gaps identified included infrequent use of guidelines, lack of referral pathways and limited knowledge, expertise and resources for treating fatigue. It is argued that further resources are required to adapt, test and implement CRF guidelines including comprehensive inter-professional training in fatigue management in cancer care.

References

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2015) Cancer-related fatigue version 1.2015. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/fatigue.pdf. Accessed 19/1/2015

Berger AM, Gerber LH, Mayer DK (2012) Cancer-related fatigue. Implications for breast cancer survivors. Cancer 118(S8):2261–2269. doi:10.1002/cncr.27475

Hilarius DL, Kloeg PH, van der Wall E, Komen M, Gundy CM, Aaronson NK (2011) Cancer-related fatigue: clinical practice versus practice guidelines. Support Care Cancer 19(4):531–538. doi:10.1007/s00520-010-0848-3

Borneman T, Piper BF, Sun VC, Koczywas M, Uman G, Ferrell B (2007) Implementing the fatigue guidelines at one NCCN member institution: process and outcomes. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 5 (10):1092–1101. doi:http://www.jnccn.org/content/5/10/1092.short

Piredda M, De Marinis MG, Rocci L, Gualandi R, Tartaglini D, Ream E (2007) Meeting information needs on cancer-related fatigue: an exploration of views held by Italian patients and nurses. Support Care Cancer 15(11):1231–1241. doi:10.1007/s00520-007-0240-0

Howell D, Keller-Olaman S, Oliver TK, Hack TF, Broadfield L, Biggs K, Chung J, Gravelle D, Green E, Hamel M, Harth T, Johnston P, McLeod D, Swinton N, Syme A, Olson K (2013) A pan-Canadian practice guideline and algorithm: screening, assessment, and supportive care of adults with cancer-related fatigue. Curr Oncol 20(3):e233–e246. doi:10.3747/co.20.1302

Willis GB (2005) Cognitive interviewing: a tool for improving questionnaire design. Sage Publications, California

Büttner P, Muller R (2011) Epidemiology. Oxford University Press, Australia

Joffe H, Yardley L (2004) Content and thematic analysis. In: Marks DF, Yardley L (eds) Research methods for clinical and health psychology. Sage Publications Ltd, Great Britain, pp 56–66. doi:10.4135/9781849209793

Elo S, Kyngäs H (2008) The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 62(1):107–115. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

Mendoza TR, Wang XS, Cleeland CS, Morrissey M, Johnson B, Wendt JK, Huber SL (1999) The rapid assessment of fatigue severity in cancer patients—use of the Brief Fatigue Inventory. Cancer 85:1186–1196. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19990301)85:5<1186::AID-CNCR24>3.0.CO;2-N

Abernethy A, Shelby-James T, Fazekas B, Woods D, Currow D (2005) The Australia-modified Karnofsky Performance Status (AKPS) scale: a revised scale for contemporary palliative care clinical practice [ISRCTN81117481]. BMC Palliat Care 4:7. doi:10.1186/1472-684X-4-7

Donnelly C, Lowe-Strong A, Rankin J, Campbell A, Allen J, Gracey J (2010) Physiotherapy management of cancer-related fatigue: a survey of UK current practice. Support Care Cancer 18(7):817–825. doi:10.1007/s00520-009-0715-2

Abdalrahim MS, Herzallah MS, Zeilani RS, Alhalaiqa F (2014) Jordanian nurses’ knowledge and attitudes toward cancer-related fatigue as a barrier of fatigue management. J Am Sci 10 (2):191–197. doi:http://www.jofamericanscience.org/journals/am-sci/am1002/

Yilmaz HB, Taş F, Muslu GK, Başbakkal Z, Kantar M (2010) Health professionals’ estimation of cancer-related fatigue in children. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 27(6):330–337. doi:10.1177/1043454210377176

de Raaf PJ, de Klerk C, Timman R, Busschbach JJ, Oldenmenger WH, van der Rijt CD (2013) Systematic monitoring and treatment of physical symptoms to alleviate fatigue in patients with advanced cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 31(6):716–723. doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.44.4216

Cramp F, Byron-Daniel J (2012) Exercise for the management of cancer-related fatigue in adults. Cochrane DB Sys Rev (11). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006145.pub3

Brown JC, Huedo-Medina TB, Pescatello LS, Pescatello SM, Ferrer RA, Johnson BT (2011) Efficacy of exercise interventions in modulating cancer-related fatigue among adult cancer survivors: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark 20(1):123–133. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0988

Kangas M, Bovbjerg DH, Montgomery GH (2008) Cancer-related fatigue: a systematic and meta-analytic review of non-pharmacological therapies for cancer patients. Psychol Bull 134(5):700–741. doi:10.1037/a0012825

Goedendorp MM, Gielissen MFM, Verhagen CAHHVM, Bleijenberg G (2009) Psychosocial interventions for reducing fatigue during cancer treatment in adults. Cochrane DB Sys Rev (1). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006953.pub2

Gibson F, Edwards J, Sepion B, Richardson A (2006) Cancer-related fatigue in children and young people: Survey of healthcare professionals’ knowledge and attitudes. Eur J Oncol Nurs 10(4):311–316. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2005.09.010

Brook RH (1989) Practice guidelines and practicing medicine: are they compatible? JAMA 1(21):3027–3030. doi:10.1001/jama.1989.03430210069032

Woolf S, Schunemann HJ, Eccles MP, Grimshaw JM, Shekelle P (2012) Developing clinical practice guidelines: types of evidence and outcomes; values and economics, synthesis, grading, and presentation and deriving recommendations. Implement Sci 7:61. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-7-61

Harrison MB, Légaré F, Graham ID, Fervers B (2010) Adapting clinical practice guidelines to local context and assessing barriers to their use. Can Med Assoc J 182(2):E78–E84. doi:10.1503/cmaj.081232

IOM (Institute of Medicine) (2011) Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC. doi:http://nap.edu/catalog/13058.htm

Prior M, Guerin M, Grimmer‐Somers K (2008) The effectiveness of clinical guideline implementation strategies—a synthesis of systematic review findings. J Eval Clin Pract 14(5):888–897. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.01014.x

Piper BF, Borneman T, Sun VC-Y, Koczywas M, Uman G, Ferrell B, James RL (2008) Cancer-related fatigue: role of oncology nurses in translating National Comprehensive Cancer Network assessment guidelines into practice. Clin J Oncol Nurs 12(5,Suppl):37–47. doi:10.1188/08.CJON.S2.37-47

Owens DK, Qaseem A, Chou R, Shekelle P (2011) High-value, cost-conscious health care: concepts for clinicians to evaluate the benefits, harms, and costs of medical interventions. Ann Intern Med 154(3):174–180. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-154-3-201102010-00007

Escalante CP, Kallen MA, Valdres RU, Morrow PK, Manzullo EF (2010) Outcomes of a cancer-related fatigue clinic in a comprehensive cancer center. J Pain Symptom Manage 39(4):691–701. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.09.010

Dainesi SM, Goldbaum M (2012) E-survey with researchers, members of ethics committees and sponsors of clinical research in Brazil: an emerging methodology for scientific research. Rev Bras Epidemiol 15(4):705–713. doi:10.1590/S1415-790X2012000400003

Simsek Z, Veiga JF (2000) The electronic survey technique: an integration and assessment. Organ Res Methods 3(1):93–115. doi:10.1177/109442810031004

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Marilyn di Stefano for supervision in the design stage of this study, the six professional societies that distributed the survey and the health professionals who participated in cognitive interviews and the survey.

Conflict of interest

None. Authors have full control of all primary data, and this will be made available to Supportive Care in Cancer if requested.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pearson, E.J.M., Morris, M.E. & McKinstry, C.E. Cancer-related fatigue: a survey of health practitioner knowledge and practice. Support Care Cancer 23, 3521–3529 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2723-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2723-8