Abstract

Purpose

Setting and pursuing personal goals is a vital aspect of our identity and purpose in life. Cancer can put pressure on these goals and may be a reason for people to adjust them. Therefore, this paper investigates (1) changes in cancer patients’ goals over time and (2) the extent to which illness characteristics relate to goal changes.

Methods

At both assessment points (1 and 7 months post-diagnosis), colorectal cancer patients (n = 198) were asked to list their current goals and rate them on hindrance of illness, attainability, likelihood of success, temporal range and importance. All goals were coded by two independent raters on content (i.e. physical, psychological, social, achievement and leisure). Patients’ medical data were obtained from the national cancer registry.

Results

Over time, patients reported a decrease in illness-related hindrance, higher attainability and likelihood of success, a decrease in total number of goals, goals with a shorter temporal range, and more physical and fewer social goals. At both assessments, patients with more advanced stages of cancer, rectal cancer, a stoma, and receiving additional chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy reported more illness-related hindrance in goal attainment, but only patients with a stoma additionally reported lower attainability, likelihood of success and more short-term goals.

Conclusions

The results of this study support the assumption that cancer patients adjust their goals to changing circumstances and additionally show how patients adjust their goals to their illness. Moreover, we demonstrate that illness variables impact on goal change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The motivation to live our lives the way we do comes from our life values, which are reflected in the goals we set and pursue [1]. The formulation, pursuit and achievement of goals are important for a person’s well-being, as without it, life loses its shape and purpose [2, 3]. However, being diagnosed with a potentially life-threatening disease such as cancer can hinder patients from attaining their goals [4–6], leading to decreases in well-being [3].

Cancer can make goals difficult to achieve for reasons such as physical side effects of treatment or time spent in the hospital. To reduce the adverse impact of the disturbance of personal goals, self-regulation theories assume that people may adjust their goals [7, 8] to keep them attainable in changed situations (i.e. goal adjustment). Given the large body of literature indicating that, in general, people are quick to adjust to adverse life events and to maintain well-being (e.g. [3, 9]), and considering the claim of theories on life-span development that people are used to adjusting to changing opportunities and resources throughout their lives (e.g. [2, 10]), it might very well be that cancer patients adjust their goals to what is attainable to maintain well-being [8, 11, 12].

To date, most empirical studies on goal adjustment have focused on people’s general tendencies when coping with disturbed goals (e.g. the tendency to disengage from disturbed goals or to re-engage in alternative and attainable goals) (e.g. [13, 14]). However, such research does not provide information on how goals actually change. More comprehensive insight into goal adjustment can be obtained by studying actual changes in goal characteristics over time [15]. Goal characteristics, termed to as goal constructs by Austin and Vancouver [16] and Carver and Scheier [3], and goal dimensions by Emmons [17] and Little [18], refer to ways in which goals can be specified and categorised according to their content and structure [16]. Goal content encompasses life domains in which goals can be grouped. For instance, goals related to health and recovery of illness can be grouped within the physical domain, as these goals have to do with people’s physical status [16]. Other life domains in which goals can be grouped are the psychological, social, achievement and leisure domains (derived from [17, 19–21]). Goal structure refers to the respondents’ appraisal of their goals on aspects on which goals are assumed to differ [16, 17], such as how important the goal is to them, how attainable it is and how much investment of effort is required to attain the goal [16–18].

To our knowledge, only Pinquart and colleagues [7] have investigated changes in cancer patients’ goals over time, and their work gives us preliminary insights into the actual goal adjustment process of cancer patients. They asked cancer patients, heterogeneous with respect to diagnosis and prognosis, to describe the goals they were pursuing at that particular moment before the start of treatment and then asked again 9 and 18 months later. In addition, they asked them to rate each goal in terms of the perceived influence of their health status on goal attainment, the likelihood of goal attainment and the anticipated time required for goal attainment. The results showed that, over time, patients reported an increase in the number of health-related goals, a decrease in having their illness hinder them from attaining their goals, a reduction in the expected likelihood of goal attainment, and the adoption of goals with a shorter time frame. The results of this study indicate that cancer patients indeed seem to adjust their goals over time to match their changed opportunities and resources for goal attainment.

In their study, however, Pinquart and colleagues did not take into account the influence of specific illness variables, while previous studies suggest that patients with different stages and types of cancer may differ in their goal adjustment [7, 8]. Indeed, illness variables may influence opportunities for goal attainment (e.g. more advanced stages of cancer and more treatment can lead to more hospital stays and more physical restraints), possibly leading to differences in how patients change their goals. Therefore, this study investigates the role of illness characteristics in how cancer patients change their goals between 1 and 7 months after diagnosis. This period was chosen because of its specific nature, characterised by initial treatment and coming to terms with the diagnosis [22], making it an important period to investigate if and how patients change their goals.

Colorectal cancer is the most common type of cancer in both men and women in Europe, with 447,000 new cases in 2012 [23]. Most patients seem to adjust well to their illness [11], although patients with more advanced stages of cancer [24, 25], rectal cancer [24–26] and a stoma [27–29] have been found to experience lower health-related quality of life. It might be that these subgroups of colorectal cancer patients experience more illness-related hindrance in goal attainment and thus report poorer well-being. Additionally, patients who receive additional treatment (i.e. chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy) to cancer surgery could experience more distress [12], physical hindrance and more uncertain views of the future than patients who have surgery only, possibly leading to differences in how they deal with their goals.

In this study, we investigated how cancer patients change their goals over the first 6 months after colorectal cancer diagnosis and whether prognosis, site of cancer (i.e. colon or rectal tumour), presence of a stoma and receiving additional treatment (i.e. chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy) were related to these changes. First, based on the literature, we hypothesised that, over time, patients would report a decline in the level of goal hindrance presented by their illness, an increase in the attainability of their goals and the expected likelihood of goal attainment, as well as adoption of goals with a shorter time frame. We did not, however, expect changes in the importance of the reported goals, as we freely elicited patients’ most important goals at both assessments. We also hypothesised that patients would report a reduction in the number of goals, in accordance with the theory of selection, optimisation and compensation (e.g. [30, 31]) which states that the selection of specific goals is a response to reduced resources such as time and energy—circumstances which are likely to be the case during the first 6 months after a colorectal cancer diagnosis. Additionally, with respect to goal content, we hypothesised that patients would formulate more health-related goals over time, visible in an increase in goals within the physical domain. Second, we hypothesised that subgroups of patients (i.e. those with a more severe prognosis, rectal cancer, presence of a stoma and receiving additional treatment) would report more hindrance presented by their illness and consequently lower levels of attainability of goals, lower levels of likelihood of success and more short-term goals.

Materials and methods

Design and participants

This study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of a university medical centre in The Netherlands. Participants were recruited from four hospitals in The Netherlands. Eligible participants were newly diagnosed colorectal cancer patients over 18 years old. Those who had cognitive impairment, were unable to understand Dutch, or had drug or alcohol problems were excluded from participation.

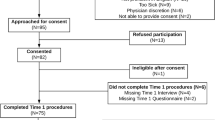

As is shown in Fig. 1, 619 eligible patients were identified. Of these, 46 patients were not approached for the study as they were already engaged in a different study, and 64 patients were not informed as the hospital staff did not provide the patients with the information package (e.g. because they were deemed too ill or were receiving further treatment in another hospital). Of the 494 patients who were approached for the study, 117 refused the information. Of the 377 patients who received the information, 225 signed an informed consent form (response rate 45.6 %). Of those patients, 216 completed the first assessment. Nine patients did not complete the first assessment after providing informed consent, mostly because they were too ill or had died (n = 6). Seventeen participants dropped out between the first and second assessments (again, mostly because they were too ill or had died, n = 13), leaving 199 patients who completed both assessments (drop-out rate 7.9 %). Additionally, for one patient, clinical data could not be supplied by the cancer registry. This patient was thus excluded from the analyses, bringing the total of the sample to 198 patients.

Procedure

Nurses or physicians briefly introduced the study and gave patients an information package as soon as their diagnosis had been confirmed. Patients were asked to read the information, complete the informed consent form if they were willing to participate and return it in a prepaid envelope to the researchers. Patients who did not send in their informed consent form within 2 weeks were contacted by phone by the researchers. Participating patients were assigned to an interviewer who was given the contact details and who scheduled an interview as soon as possible. After 6 months, all patients were again contacted for their second interview by the same interviewer. Interviews were conducted at a place of the patient’s choosing, usually their homes. Most patients were interviewed within approximately a month after they had received the information package (median = 27 days; mean = 35 days, SD = 26.9).

Measures

Goals

At both assessments, participants were asked to list a minimum of three and a maximum of ten current goals by means of an open question (based on [17]). It was explained that goals could be their plans, things they wanted to achieve or projects they were currently working on.

With respect to goal content, each goal was classified by two independent raters into one of five life domains: physical (e.g. regaining health), psychological (e.g. aiming for personal growth), social (e.g. spending time with friends or family), achievement (e.g. working on career) and leisure (e.g. enjoying a holiday) [17, 19, 20]. Disagreement was resolved with a third rater.

With respect to goal structure, the following aspects were assessed: importance, illness-related hindrance, attainability, likelihood of success and temporal range. At both assessments, respondents rated each of their goals on their appraisal of how important the goal was to them, how much the illness hindered them from attaining the goal, how attainable the goal was, how likely it was that the goal would be reached and the time frame within which they expected to reach their goal (based on [16, 17, 20]). Ratings were given on Likert scales ranging from 1 (not at all) to 10 (very) for importance, level of hindrance presented by illness and goal attainability, from 1 (0 %) to 10 (100 %) for likelihood of success and from 1 (within 1 week) to 9 (more than 2 years) for the temporal range [17].

Objective illness characteristics

All information concerning illness characteristics was obtained by matching participants’ data with their medical data from The Netherlands Cancer Registry (NCR). The NCR collects medical data on all cancer patients in The Netherlands, and the data are available for research purposes.

Prognosis

The TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours staging system used by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC, 7th edition), which ranges from stages I (local tumour without metastases) to IV (invasive tumour with metastases), was used to create prognosis groups. Stages I and II (5-year disease-specific survival rates 95 % and 84.7 %, respectively) [32] were combined to make a prognosis group with ≥80 % chance of survival at diagnosis. Stages III and IV (5-year disease-specific survival rates 68.7 % and 8.1 %, respectively) [32] were combined to make a prognosis group with <80 % chance of survival at diagnosis.

Site of cancer

Patients with tumours located anywhere in the colon and sigmoid were grouped to form the colon cancer group. Patients with tumours located in the rectum and anus were grouped to form the rectal cancer group. This division was made based on the similar treatment procedures used with colon and sigmoid tumours (mostly surgery) vs. tumours of the rectum and anus (mostly radiotherapy).

Presence of stoma

Patients who indicated that they had either a permanent or temporary stoma at the second assessment were grouped into a stoma group.

Treatment

Patients who received surgery only were grouped to form the surgery only group, while patients who also received chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy were grouped into the surgery plus additional treatment group.

Statistical analyses

We used descriptive statistics to examine characteristics of the sample and chi-square tests to test for associations between categorical variables. Paired sample t tests were used to examine changes in goals over time. Using prognosis, site of cancer, presence of stoma and additional treatment as between-groups factors, repeated measures analyses of variance were used to examine changes in goal characteristics over time as well as possible interaction effects. Regarding prognosis, additional post hoc tests for all four stages of illness were performed. A p value of .05 was considered significant throughout, and all statistical analyses were done using SPSS version 21.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants. Since The Netherlands Cancer Registry reports that 48.7 % of all reported colorectal cancer patients in The Netherlands are female and the mean age of diagnosis is 67 years, the sample used in the current study appears to be fairly representative of Dutch colorectal cancer patients.

The majority of patients were diagnosed with either stage I or stage II colorectal cancer, with 110 patients (55.5 %) in the prognosis group with ≥80 % chance of survival at diagnosis and 76 patients (38.4 %) in the group with <80 % chance of survival at diagnosis. Twelve patients (6.1 %) could not be staged. Most patients were diagnosed with cancer of the colon and sigmoid (n = 121, 61.1 %). The remaining 77 patients (38.8 %) had a tumour in the rectum or anus. Sixty-two patients (31.3 %) had a stoma at the second assessment (T2). Patients with rectal cancer had a stoma more often than did colon cancer patients (χ 2 = 45.79, p < .001).

For one patient, no data on treatment was available. Of the 197 remaining patients, 85 (43.8 %) were treated with surgery alone and 109 patients (56.2 %) were treated with chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy in addition to surgery. Three patients did not have surgery but only chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy. These three patients, together with the patient of whom no data on treatment was available, were excluded from the analyses comparing treatment conditions.

Impact of illness on goals over time

Table 2 shows the results of the paired sample t tests examining changes in goal characteristics over time. Supporting our hypotheses, patients did indeed report significantly less illness-related hindrance in attaining their goals, higher attainability and likelihood of success, a shorter time frame within which they wanted to attain their goals, and significantly fewer goals over the course of 6 months. Contradicting our hypothesis, patients reported goals with a significantly higher level of importance over time.

Furthermore, over time, patients reported significantly more physical and fewer social goals. No changes were found in the number of psychological, achievement and leisure goals.

Effect of illness variables on goals over time

Table 3 shows the results of the repeated measures analyses of variance with illness variables as a between-groups factor.

Prognosis

The 12 patients who could not be staged with respect to their prognosis were not included in this analysis. A significant association was found between prognosis and the level of hindrance presented by illness in attaining goals, but not for the other structural aspects of goals (i.e. attainability, likelihood of success, temporal range and importance). Mean scores show that patients with <80 % chance of survival at diagnosis (i.e. stages III and IV) had higher levels of illness-related hindrance in their goals at both measurement times. Post hoc tests were performed to make sure that no information was missed when combining the four stages into two groups and to detect potential differences between the four separate stage groups (I, II, III and IV). Results show that at both assessments, patients with stage IV cancer had significantly higher levels of hindrance presented by illness than patients with stages I and II, but this was not the case for patients with stage III cancer. The post hoc tests of prognosis and the other goal structure aspects did not reveal any significant differences between stage groups. Furthermore, no interaction effect was found between time and prognosis, indicating that the goals did not change in different ways for the patients with <80 % chance of survival at diagnosis compared with those with ≥80 % chance of survival at diagnosis.

Site of cancer

A significant effect of cancer site was found only for level of hindrance presented by illness. Patients with rectal cancer experienced higher levels of hindrance due to illness at both measurement times compared to colon cancer patients. A trend towards an effect of cancer site on temporal range was found (p = .06). Patients with rectal cancer reported goals with a longer temporal range at both assessment points than did colon cancer patients. No time × cancer site interaction was found, indicating that the goals did not change in different ways for patients with a colon vs. a rectal carcinoma.

Stoma

The presence of stoma showed a significant effect on all structural aspects of goals: hindrance due to illness, attainability, likelihood of success and temporal range. Patients who had a stoma reported more illness-related hindrance, lower goal attainability and likelihood of success, but a longer temporal range, than patients without a stoma at both assessment points. A significant interaction effect of time and presence of stoma was found for illness-related hindrance. While patients without a stoma reported a decrease in hindrance due to illness over time, patients with a stoma did not.

Treatment

A significant effect for receiving additional treatment was found only for illness-related hindrance. Patients who received chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy in addition to surgery had higher levels of hindrance in attaining their goals at both assessments. The groups did not differ on other structural aspects, and no significant interaction effects were found.

Discussion

The current paper is the first to examine both the changes in cancer patients’ goals in the first 6 months after diagnosis and the influence of illness variables. As hypothesised, the results show that over a course of 6 months after diagnosis, colorectal cancer patients experienced a reduction in the level of hindrance presented by their illness in attaining their goals, an increase in goal attainability and a higher likelihood of success in the attainment of their goals. Additionally, they formulated goals that had lower importance, shorter time frames and were fewer in number overall. Also, they reported more physical and fewer social goals. Moreover, as expected, patients with a <80 % chance of survival, rectal cancer, a stoma and those who received additional chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy experienced more illness-related hindrance in attaining their goals than did patients with a ≥80 % chance of survival, colon cancer, no stoma and no additional treatment, both at the assessment soon after diagnosis as well as 6 months later.

The findings of changes in goal characteristics and goal content provide further evidence for the assumption that cancer patients actually adjust their goals to better fit their new circumstances. Given the recent findings [8] that patients adjust their goals to maintain well-being, a next step would be to investigate further the relations between actual goal adjustment and well-being.

A notable finding was that patients with more advanced stages of illness, rectal cancer, who received chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy and especially patients with a stoma experienced more problems with goal adjustment. Stoma patients reported more hindrance in attainment of their goals due to their illness, lower levels of goal attainability and a lower expected likelihood of success in attaining their goals. Previous research has shown that having a stoma is associated with more need for changes in lifestyle on a daily basis [33, 34], as well as a changed body image [35], which suggests that such patients might have a greater need to adjust their goals. Patients with a stoma might benefit from support in adjusting their life to having a stoma, perhaps by providing more information on the prospect of living with a stoma, as well as practical stoma care to better deal with the limitations.

Although this study has several methodological strengths, such as a longitudinal design, a large sample size, a low drop-out rate and a strong method for assessing goals (mixed ideographic–nomothetic technique), several limitations need to be acknowledged. First, no control group was included as a reference in order to distinguish changes in goals due to cancer from those due to other reasons. However, as we were only interested in changes over time taking illness variables into account—which cannot be assessed in a healthy control group—this should not have influenced our conclusions. Second, the first assessment took place approximately a month after diagnosis, which may have led to the omission of adjustments that had already taken place before the start of the study. Third, patients who died during follow-up were excluded from the study, and therefore, the data of these patients were not available for analysis. This is similar to other longitudinal studies on cancer patients [7] but could nevertheless have made the effects of illness stage on goal change less marked than could be expected. Fourth, the low number of patients in the more advanced stages of illness led us to combine stage III and stage IV patients, with widely diverse survival rates. We did, however, perform post hoc analyses with all four groups, to obtain indications of how the groups differed from each other. Lastly, we focused only on the first 6 months after diagnosis. It could be that changes in life goals are still continuing long after this period [7], and such changes would have therefore been missed in this study.

Suggestions for future research include studies with longer follow-up times, larger sample sizes (to be able to compare different treatment trajectories in more detail) and qualitative research involving more in-depth exploration of how and why cancer patients change their goals in the context of the illness. The current study builds on existing ideas concerning goal adjustment (i.e. studying mean changes of goal characteristics over time) [7, 8], but it would be interesting to investigate alternative ideas on goal adjustment in cancer (e.g. investigating actual goal adjustment strategies from theory, such as shifting priorities or continuing to pursue disturbed goals [2, 36]).

In conclusion, this study has shown that overall, colorectal cancer patients maintain attainable goals over the first 6 months after diagnosis. Furthermore, the hindrance of their illness in pursuing their goals reduces, even in those patients with more severe stages of cancer, rectal cancer and receiving chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy. Stoma patients were the only group of patients not to report a reduction of illness-related hindrance. Combined with our findings that patients report differences in the time frame in which they expect to attain their goals as well as in the types of goals they choose to pursue, these results suggest that patients adjust their goals to what is feasible when diagnosed with cancer. This study therefore provides more concrete support for the suggestion that goals play an important role in the adjustment process for cancer patients.

References

Emmons RA (1996) Striving and feeling: personal goals and subjective well-being. In: Gollwitzer PM, Bargh JA, Gollwitzer PM, Bargh JA (eds) The psychology of action: linking cognition and motivation to behavior. Guilford Press, New York, pp 313–337

Heckhausen J, Wrosch C, Schulz R (2010) A motivational theory of life-span development. Psychol Rev 117:32–60

Carver CS, Scheier MF (1998) On the self-regulation of behavior. Cambridge University Press, New York

Affleck G, Tennen H, Zautra A, Urrows S, Abeles M, Karoly P (2001) Women’s pursuit of personal goals in daily life with fibromyalgia: a value-expectancy analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol 69:587–596

Boersma SN, Maes S, Joekes K (2005) Goal disturbance in relation to anxiety, depression, and health-related quality of life after myocardial infarction. Qual Life Res 14:2265–2275

Offerman MPJ, Schroevers MJ, van der Velden L, de Boer MF, Pruyn JFA (2010) Goal processes & self-efficacy related to psychological distress in head & neck cancer patients and their partners. Eur J Oncol Nurs 14:231–237

Pinquart M, Fröhlich C, Silbereisen RK (2008) Testing models of change in life goals after a cancer diagnosis. J Loss Trauma 13:330–351

Von Blanckenburg P, Seifart U, Conrad N, Exner C, Rief W, Nestoriuc Y (2014) Quality of life in cancer rehabilitation: the role of life goal adjustment. Psychooncology 23:1149–1156

Diener E, Suh EM, Lucas RE, Smith HL (1999) Subjective well-being: three decades of progress. Psychol Bull 125:276–302

Freund AM (2008) Successful aging as management of resources: the role of selection, optimization, and compensation. Res Hum Dev 5:94–106

Dunn J, Ng SK, Breitbart W, Aitken J, Youl P, Baade PD, Chambers SK (2013) Health-related quality of life and life satisfaction in colorectal cancer survivors: trajectories of adjustment. Health Qual Life Outcome 11:46

Henselmans I, Helgeson VS, Seltman H, de Vries J, Sanderman R, Ranchor AV (2010) Identification and prediction of distress trajectories in the first year after a breast cancer diagnosis. Health Psychol 29:160–168

Brandtstädter J, Renner G (1990) Tenacious goal pursuit and flexible goal adjustment: explication and age-related analysis of assimilative and accommodative strategies of coping. Psychol Aging 5:58–67

Wrosch C, Scheier MF, Miller GE, Schulz R, Carver CS (2003) Adaptive self-regulation of unattainable goals: goal disengagement, goal reengagement, and subjective well-being. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 29:1494–1508

Rapkin BD (2000) Personal goals and response shifts: understanding the impact of illness and events on the quality of life of people living with AIDS. In: Sprangers MAG (ed) Adaptation to changing health: response shift in quality-of-life research. American Psychological Association, Washington, pp 53–71

Austin JT, Vancouver JB (1996) Goal constructs in psychology: structure, process, and content. Psychol Bull 120:338–375

Emmons RA (1999) The psychology of ultimate concerns: motivation and spirituality in personality. Guilford Press, New York

Little BR (1983) Personal projects: a rationale and method for investigation. Environ Behav 15:273–309

Grouzet FME, Kasser T, Ahuvia A, Dols JMF, Kim Y, Lau S, Ryan RM, Saunders S, Schmuck P, Sheldon KM (2005) The Structure of Goal Contents Across 15 Cultures. J Pers Soc Psychol 89:800–816

Little BR, Salmela-Aro K, Phillips SD (2007) Personal project pursuit: goals, action, and human flourishing. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, Mahwah

Pinquart M, Nixdorf-Hänchen JC, Silbereisen RK (2005) Associations of age and cancer with individual goal commitment. Appl Dev Sci 9:54–66

Stanton AL, Ganz PA, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, Krupnick JL, Sears SR (2005) Promoting adjustment after treatment for cancer. Cancer (Suppl) 104:2608

Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Lortet-Tieulent J, Rosso S, Coebergh JWW, Comber H, Forman D, Bray F (2013) Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur J Cancer 49:1374–1403

Paika V, Almyroudi A, Tomenson B, Creed F, Kampletsas EO, Siafaka V, Gkika S, Mavreas V, Pavlidis N, Hyphantis T (2010) Personality variables are associated with colorectal cancer patients’ quality of life independent of psychological distress and disease severity. Psychooncology 19:273–282

Steginga SK, Lynch BM, Hawkes A, Dunn J, Aitken J (2009) Antecedents of domain-specific quality of life after colorectal cancer. Psychooncology 18:216–220

Ohigashi S, Hoshino Y, Ohde S, Onodera H (2011) Functional outcome, quality of life, and efficacy of probiotics in postoperative patients with colorectal cancer. Surg Today 41:1200–1206

Chambers SK, Meng X, Youl P, Aitken J, Dunn J, Baade P (2012) A five-year prospective study of quality of life after colorectal cancer. Qual Life Res 21:1551–1564

Sprangers MAG, Taal BG, Aaronson NK, te Velde A (1995) Quality of life in colorectal cancer: stoma vs. nonstoma patients. Dis Colon Rectum 38:361–369

Wilson TR, Alexander DJ, Kind P (2006) Measurement of health-related quality of life in the early follow-up of colon and rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 49:1692–1702

Baltes PB, Baltes MM (1990) Psychological perspectives on successful aging: the model of selective optimization with compensation. In: Baltes PB, Baltes MM, Baltes PB, Baltes MM (eds) Successful aging: perspectives from the behavioral sciences. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp 1–34

Freund AM, Baltes PB (1998) Selection, optimization, and compensation as strategies of life management: correlations with subjective indicators of successful aging. Psychol Aging 13:531–543

Hari DM, Leung AM, Lee J, Sim M, Vuong B, Chiu CG, Bilchik AJ (2013) AJCC Cancer Staging Manual 7th Edition Criteria for Colon Cancer: do the complex modifications improve prognostic assessment? J Am Coll Surg 217:181–190

Bekkers MJTM, Van Knippenberg FCE, Van Den Borne HW, Van Berge-Henegouwen GP (1996) Prospective evaluation of psychosocial adaptation to stoma surgery: the role of self-efficacy. Psychosom Med 58:183–191

Wu HK, Chau JP, Twinn S (2007) Self-efficacy and quality of life among stoma patients in Hong Kong. Cancer Nurs 30:186–193

Sharpe L, Patel D, Clarke S (2011) The relationship between body image disturbance and distress in colorectal cancer patients with and without stomas. J Psychosom Res 70:395–402

Haase CM, Heckhausen J, Wrosch C (2013) Developmental regulation across the life span: toward a new synthesis. Dev Psychol 49:964–972

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Dutch Cancer Society (RUG 2009–4461).

Medical records were supplied by The Netherlands Cancer Registry, managed by the Comprehensive Cancer Centre of The Netherlands.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Janse, M., Ranchor, A.V., Smink, A. et al. Changes in cancer patients’ personal goals in the first 6 months after diagnosis: the role of illness variables. Support Care Cancer 23, 1893–1900 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2545-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2545-0