Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to explore the perceived need for supportive care including healthy lifestyle programs among cancer survivors, their attitude towards self-management and eHealth, and its association with several sociodemographic and clinical variables and quality of life.

Methods

A questionnaire on the perceived need for supportive care and attitude towards self-management and eHealth was completed by 212 cancer survivors from an online panel.

Results

Highest needs were reported regarding physical care (66 %), followed by healthy lifestyle programs (54 %), social care (43 %), psychological care (38 %), and life question-related programs (24 %). In general, cancer survivors had a positive attitude towards self-management and eHealth. Supportive care needs were associated with male gender, lower age, treatment with chemotherapy or (chemo)radiation (versus surgery alone), hematological cancer (versus skin cancer, breast cancer, and other types of cancer), and lower quality of life. A positive attitude towards self-management was associated with lower age. A more positive attitude towards eHealth was associated with lower age, higher education, higher income, currently being under treatment (versus treatment in the last year), treatment with chemotherapy or (chemo)radiation (versus surgery alone), prostate and testicular cancer (versus hematological, skin, gynecological, and breast cancer and other types of cancer), and lower quality of life.

Conclusions

The perceived need for supportive care including healthy lifestyle programs was high, and in general, cancer survivors had a positive attitude towards self-management and eHealth. Need and attitude were associated with sociodemographic and clinical variables and quality of life. Therefore, a tailored approach seems to be warranted to improve and innovate supportive care targeting cancer survivors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cancer survivors often experience unmet needs regarding supportive care targeting daily living and communication and the psychological, social, physical, sexuality, and spiritual domains of quality of life [1, 2]. Cancer survivors may also be in need for healthy lifestyle programs, since they often engage in risky health behavior (sedentary lifestyle, unhealthy diet, smoking, and drinking) [3].

Unmet supportive care needs may be caused by changes in the health-care system in which the amount of time with health-care providers is limited [4], health-care costs are increasing [5], and the distance to the hospital is increased due to centralization of care [6, 7], hampering referral to supportive care in patients’ own surroundings. To improve accessibility of supportive care, cancer survivors are expected to adopt an active role in managing their own care. Self-management is defined by McCorkle et al. [4] as “those tasks that individuals undertake to deal with the medical, role, and emotional management of their health condition(s).” Accessibility of supportive care may also be improved by providing eHealth (“information and communications technology, especially the Internet, to improve or enable health and health care” [8]) alongside usual care. eHealth has high confidentiality experience among cancer patients [9] and has the potential to be cost-effective and to improve physical activity level [10], smoking status [11], patient empowerment [10], psychological well-being [9, 12], and quality of life [12].

Previous qualitative studies on self-management reported that cancer patients are interested in managing their own care [13, 14], since this gives them a sense of control [14]. Barriers reported concerned time and energy constraints, lack of knowledge on cancer and its treatment, and problems with navigation in the health-care system [13, 14]. Regarding eHealth, several cancer survivors find applications by which they receive online patient support [15, 16] or online contact with their health-care professional [16, 17] appealing.

To be able to provide cancer survivors with optimal supportive care, insight into their perceived needs including healthy lifestyle programs and their attitude towards self-management and eHealth is required. Although several studies have focused on the supportive care needs of cancer survivors, much less is known on their need for healthy lifestyle programs and their attitude towards self-management and eHealth. Moreover, no study has investigated the need for supportive care and attitude towards self-management and eHealth in the same population. Therefore, the main aim of this study was to describe the perceived need for supportive care including healthy lifestyle programs among cancer survivors and their attitude towards self-management and eHealth.

Furthermore, information on factors associated with the need for supportive care and with a positive attitude towards self-management and eHealth is valuable, since this information may guide health-care resource allocation to subgroups most likely to benefit from supportive care including self-management and eHealth.

Previous studies reported that cancer survivors with (unmet) supportive care needs are younger [18–26] and have a lower income [23, 26] and a lower quality of life [22, 27]. In addition, higher (unmet) supportive care needs were associated with being female [19, 22, 28], except for the sexuality domain [18, 19, 21]. Inconclusive findings were reported regarding cancer diagnosis and type of treatment. Lower (unmet) supportive care needs were reported in melanoma cancer patients (versus breast, colorectal, blood, lung, and prostate cancer) [18], colorectal cancer patients (versus breast cancer, lymphoma, and lung cancer) [22], as well as breast cancer patients (versus multiple cancer sites, lung cancer, colorectal cancer, brain cancer, and other types of cancer) [19]. Regarding the type of treatment, some studies reported no differences in (unmet) supportive care needs in patients treated with multiple treatments compared to a single treatment [21, 25], while Sanson-Fisher et al. [19] reported lower unmet needs in patients treated with multimodal treatments compared to patients treated with chemotherapy. Studies investigating education level [18, 20, 21, 23, 25, 28] and time since the last treatment [20, 23, 25] mainly reported an absence of an association with (unmet) supportive care needs.

Less is known on the relation between several sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and attitude towards self-management and eHealth. Attitude itself seems to predict the intention to engage in online peer support [15], while the usage of an online discussion group was reported to be associated with lower age and the usage of a participant-expert communication service with lower education level [29].

Therefore, the second aim of this study was to explore if sociodemographic and clinical variables and quality of life are associated with perceived supportive care needs and attitude towards self-management and eHealth among cancer survivors.

Methods

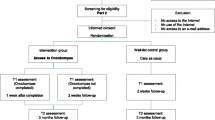

Design and study population

In this cross-sectional study, data was collected via an online Dutch panel (StemPunt) of the marketing agency “Motivaction”. This panel consists of 70,000 persons and represents the Dutch population aged 18–70 years. For this study, persons diagnosed with cancer (n = 822) were asked to complete a study-specific online questionnaire, of which 339 persons (41 %) completed the questionnaire. In order to provide information on the perceived need for supportive care and attitude towards self-management and eHealth of cancer survivors (i.e., patients without recurrence or metastasis), all persons diagnosed with cancer for the first time from 2001 until 2011, without metastases or multiple primary cancers, were included. In total, 212 cancer survivors (63 %) matched the inclusion criteria. Characteristics of the study sample are described in Table 1.

Measures

For this study, the survey was composed of several study-specific items and questionnaires, based on the literature and our earlier research on supportive care, self-management, and eHealth [16, 30, 31]. The study-specific questions and statements are presented in Tables 2, 3, 4, and 5. The perceived needs for supportive care were assessed using a five-item study-specific questionnaire. Cancer survivors were asked to report their need for psychological care, social care, physical care, life question-related programs, and healthy lifestyle programs on a four-point Likert scale. Answers were dichotomized into no need (no need and little need) and a need (some and strong need). When cancer survivors reported a need for supportive care, they were asked about their preferred supportive care type (individual or in groups, and with or without counseling, aids, or coaching). All cancer survivors were asked about their preferred setting for receiving supportive care (e.g., hospital, community center, or the Internet) and whether they had unmet needs.

Attitude towards self-management was measured with an 11-item study-specific questionnaire. Cancer survivors were asked to report their level of agreement with different propositions, e.g., “If I require medical treatment then I wish to choose a physician myself.” on a five-point Likert scale. Answers were dichotomized into disagree/neutral (completely disagree, disagree, and neither agree nor disagree) or agree (agree and completely agree). Since principal component analysis did not provide clear underlying constructs due to low intercorrelation of the items (only four out of 55 correlations had a Pearson’s correlation of >0.30), based on McCorkle’s definition of self-management [4], the item on medical management of their health condition (If, for medical reasons, I need to improve my health, then I want to decide myself what has to be done) was used as an outcome variable in the regression analysis.

Attitude towards eHealth was measured with an eight-item study-specific questionnaire. Cancer survivors were asked to rate on a four-point Likert scale (does not appeal to me to does appeal to me) whether, for example, an Internet intervention that helps or supports with changing their lifestyle was appealing to them. Based on principal component analyses with varimax rotation, two underlying constructs were found (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) Measure of Sampling Adequacy = 0.80 and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity Chi-Square = 617.259, p < 0.001), namely a construct on self-management by means of eHealth consisting of four items and a construct on online contact with health-care professionals also consisting of four items (Table 4). Both constructs showed good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.76 and 0.85). Total score per construct was converted to a standardized 0–100 score. In addition to the attitude items, the perceived attractiveness of several eHealth applications (e.g., self-monitoring of side effects and symptoms) was measured using an eight-item study-specific questionnaire. Cancer survivors could answer these items on a five-point Likert scale. Answers were categorized into unattractive/neutral (very unattractive, unattractive, or neutral) and attractive (attractive or very attractive).

Quality of life was measured with the EQ-5D (EuroQol), which consists of five items measuring problems on five dimensions of quality of life (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression). Cancer survivors could answer that they had no problems, some problems, or extreme problems [32].

Sociodemographic variables (age, gender, education, and bruto household income) and clinical variables (time since treatment, type of treatment, and cancer diagnosis) were self-reported. Education level was categorized into low (i.e., primary school and primary stage of secondary education), medium (i.e., secondary stage of secondary education), and high (i.e., university) [33]. Bruto household income was categorized into below modal (Dutch modal income ranges from €30.500 to €36.399 a year), modal, and above modal and into a subgroup who did not know or did not want to tell.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were performed using the IBM Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS) version 20 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to describe the sociodemographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, and quality of life of the study population as well as the perceived need for supportive care and attitude towards self-management and eHealth. Logistic and linear multivariate regression analyses were performed via a forward selection procedure (p value for enter <0.1) to assess the association between sociodemographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, and quality of life with the perceived need for supportive care, attitude towards self-management, and attitude towards eHealth.

Results

Perceived need for supportive care

In total, 78 % of all cancer survivors reported one or multiple supportive care needs and 25 % of all cancer survivors reported unmet needs. Highest perceived needs were reported regarding physical care (66 %), followed by healthy lifestyle programs (54 %), social care (43 %), psychological care (38 %), and life question-related programs (24 %) (Table 2). The most preferred type of supportive care was individual professional counseling (48–67 %), followed by self-help without support (14–28 %), a supported online self-help program (17–25 %), and care in groups with professional counseling (17–21 %). The preferred setting for obtaining supportive care was the hospital (36 %), followed by general practice (34 %), the Internet (13 %), community cancer center (13 %), community care center in the neighborhood (10 %), cancer consultation center in the neighborhood (9 %), center for psychosocial cancer care (8 %), and patient association (6 %).

Attitude towards self-management

Cancer survivors had a positive attitude towards managing their own health, especially regarding which physician to choose (77 %) and deciding themselves what to do to improve their health (66 %) (Table 3). The majority of cancer survivors reported being capable of judging whether their symptoms were serious (53 %). Only a small part of cancer survivors responded positively towards checking their health themselves instead of visiting a physician (13 %). In addition, many cancer survivors reported to fully trust their physician (65 %) and to follow the physician’s recommendation (82 %).

Attitude towards eHealth

Cancer survivors had a positive attitude towards eHealth (Table 4), especially regarding providing information about medical symptoms or sickness (87 %) and healthy lifestyle (83 %) as well as scheduling appointments with their health-care professionals (83 %). Attractive eHealth applications to manage their health were as follows: obtaining personalized advice on how to handle the consequences of cancer in their situation or to better cope with the consequences (51 %), obtaining insight into their own lifestyle (50 %), and monitoring side effects and symptoms (48 %) (Table 5).

Factors associated with perceived need for supportive care

Gender, age, type of treatment, cancer diagnosis, and quality of life were associated with having one or multiple supportive care needs, including healthy lifestyle programs (Nagelkerke R 2 ranged from 0.06 to 0.17) (Table 6). Females were less often in need for healthy lifestyle programs compared to males [odds ratio (OR) = 0.53; 95 % confidence interval (CI) = 0.27 to 1.03]. Cancer survivors aged 65 years or older less often had supportive care needs regarding social care than cancer survivors younger than 50 years (OR = 0.26; 95 % CI = 0.10 to 0.70). Regarding clinical characteristics, cancer survivors treated with chemotherapy or (chemo)radiation were more often in need for a healthy lifestyle program than cancer survivors treated with surgery alone (OR = 2.50; 95 % CI = 1.04 to 6.02). Compared to cancer survivors with hematological cancer (reference category), cancer survivors with skin cancer (OR = 0.10; 95 % CI = 0.02 to 0.38) or other types of cancer (OR = 0.30; 95 % CI = 0.08 to 1.04) less often had supportive care needs regarding social care. Cancer survivors with skin cancer (OR = 0.03; 95 % CI = 0.00 to 0.23), breast cancer (OR = 0.10; 95 % CI = 0.01 to 0.82), or other types of cancer (OR = 0.11; 95 % CI = 0.01 to 0.92) less often had supportive care needs regarding physical care, compared to cancer survivors with hematological cancer (reference type). A higher quality of life score (score ≥ 0.7) was associated with supportive care needs for psychological care, life question-related programs, and healthy lifestyle programs (0.18 ≤ OR ≤ 0.38).

Factors associated with attitude towards self-management

Cancer survivors aged 50 years or older less often agreed with the proposition “If, for medical reasons, I need to improve my health, then I want to decide myself what has to be done” than patients younger than 50 years (0.17 ≤ OR ≤ 0.38) (Nagelkerke R 2 = 0.09) (Table 6).

Factors associated with attitude towards eHealth

Age, education, bruto household income, time since treatment, type of treatment, cancer diagnosis, and quality of life were associated with a positive attitude towards eHealth (R 2 = 0.18 and 0.20) (Table 6). Cancer survivors aged 60–65 years had a less positive attitude towards self-management by means of eHealth (β = −9.1; 95 % CI = −19.4 to 1.2), and cancer survivors aged 65 years or older had a less positive attitude towards contact with health-care professionals by the Internet (β = −10.4; 95 % CI = −21.6 to 0.8) compared to cancer survivors younger than 50 years (reference category). Cancer survivors with a higher education had a more positive attitude towards contact with health-care professionals by the Internet than lower-educated cancer survivors (β = 10.2; 95 % CI = −1.1 to 21.6). Cancer survivors with an income above modal had a more positive attitude towards self-management by means of eHealth than cancer survivors with an income below modal (β = 8.5; 95 % CI = 0.2 to 16.8). Regarding clinical characteristics, cancer survivors treated in the last year had a less positive attitude towards self-management by means of eHealth than cancer survivors currently under treatment (β = −11.9; 95 % CI = −23.4 to −0.4). Compared to cancer survivors with prostate or testicular cancer (reference category), cancer survivors with hematological cancer (β = −16.2; 95 % CI = −30.5 to −1.9) and other types of cancer (β = −14.4; 95 % CI = −27.7 to −1.1) had a less positive attitude towards self-management by means of eHealth. Cancer survivors with hematological cancer (β = −23.2; 95 % CI = −39.1 to −7.4), skin cancer (β = −18.1; 95 % CI = −32.6 to −3.6), breast cancer (β = −26.6; 95 % CI = −40.1 to −13.1), gynecological cancer (β = −20.8; 95 % CI = −40.7 to −0.8), and other types of cancer (β = −13.4; 95 % CI = −28.4 to 1.5) had a less positive attitude regarding contact with health-care professionals by the Internet compared to cancer survivors with prostate or testicular cancer (reference category). A higher quality of life (score of 0.9–1.0) compared to a lower quality of life (score < 0.7) was associated with a less positive attitude regarding self-management by means of eHealth (β = −8.6; 95 % CI = −17.9 to 0.7) and contact with health-care professionals by the Internet (β = −14.2; 95 % CI = −24.9 to −3.4).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore the perceived need for supportive care including healthy lifestyle programs among cancer survivors, their attitude towards self-management and eHealth, and its association with several sociodemographic and clinical variables and quality of life.

Results showed that the majority of cancer survivors had one or multiple supportive care needs and that a quarter of all cancer survivors had unmet needs, which fits into the wide range of 1–93 % of patients with unmet needs as reported by Harrison et al. [1].

Our study also explored cancer survivors’ perceived need for a healthy lifestyle program, which was reported in over half of the respondents. This is in accordance with a study of Badr et al. [34], who reported that the majority of cancer survivors were interested in weight control or healthy diet programs. Interventions targeting cancer survivors’ lifestyle have a potential beneficial effect on several lifestyle-related outcomes such as physical fitness, strength, diet, and quality of life [35]. Improving healthy lifestyle in cancer survivors may decrease risk of cancer recurrence and mortality and improve quality of life [36].

The most preferred type of supportive care in our study was individual professional counseling. This is in agreement with a previous study [23], in which a high preference rate regarding individual consultations with a psychologist was found. Although individual counseling is effective [37], it places a major burden on time of health-care professionals and health-care budget [9]. Besides, Nekolaichuk et al. [38] reported that cancer patients have concerns related to the availability which is mostly limited to daytime. Therefore, a promising result of our study is that a substantial group in need for supportive care preferred a supported online self-help program.

The finding that supported online self-help programs may be promising was further supported by our finding that cancer survivors, in general, had a positive attitude towards self-management. However, several cancer survivors included in our study also reported to feel unable to judge the seriousness of their side effects and symptoms. In a study of Schulman-Green et al. [13], cancer survivors described self-management as emotionally challenging because of worries regarding making the wrong choices on cancer and its treatment. For these cancer survivors, offering self-management programs as part of usual health care (blended care) may be promising. Blending of a supported online self-help program in usual care was reported to improve patients’ motivation to participate in a supported online self-help program [39].

Our study also showed that cancer survivors had a positive attitude towards self-management by means of eHealth and contact with health-care professionals by the Internet. Several advantages of eHealth for patients are evident, such as the high flexibility in its use regarding place and time and the opportunity to adequately formulate questions and understand responses in their communication with health-care professionals [17]. Also, health-care professionals expect that eHealth could potentially contribute to an increased quality of care, especially regarding meeting patients’ care needs [17, 40]. However, they also have concerns regarding online contact with their patients, such as increased workload, time demands, problems regarding confidentiality and security, lack of reimbursement, and inappropriate use by patients [40]. Since it is clear that health-care professionals and cancer survivors have different demands related to eHealth applications, both should be involved in the development in order to meet end-users’ needs and wishes [41].

Our study showed variation in perceived need for supportive care and attitude towards self-management and eHealth among groups of cancer survivors. Males were more likely to report supportive care needs regarding healthy lifestyle programs, which is in contrast with a previous study in which females were more interested in a healthy diet intervention [34]. In accordance with previous studies [19, 20, 22, 23, 25, 26], we found that older cancer survivors less often had supportive care needs regarding social functioning. It has been hypothesized that older cancer survivors experience lower supportive care needs due to lower impact of cancer on daily life, including work and caring for the family [2]. We also showed that older cancer survivors reported a less positive attitude towards self-management and eHealth, which was in accordance with the study of Ventura et al. [29] in which higher age was associated with lower eHealth usage. Less positive attitude towards self-management may be explained by the number of comorbidities in older persons [42], which may negatively influence self-management ability [43].

We also found variation in perceived supportive care needs and attitude towards eHealth among different cancer diagnosis groups. In line with our finding that hematological cancer survivors more often had supportive care needs regarding social and physical care, Boyes et al. [18] reported that hematological cancer survivors have higher physical and daily living supportive care needs. Regarding eHealth, we found that prostate and testicular cancer survivors had a more positive attitude towards online contact with health-care professionals. Differences in the use of eHealth between breast and prostate cancer patients were also evident in the study of Børøsund et al. [44]. A more positive attitude towards eHealth in prostate and testicular cancer patients may be explained by the intimate symptoms encountered, such as incontinence, reduced sexual functioning, and infertility [20]. This may lead to a preference to manage these symptoms online, because of privacy concerns.

In the present study, cancer survivors were included from an online research panel, which may have hampered generalizability to other patient populations (i.e., patients with recurrence or metastasis) and may have resulted in an overestimation of a positive attitude towards eHealth. However, since eHealth is targeting especially patients with eHealth literacy [45], results may also be suggested to be representative.

In addition, a short questionnaire of supportive care needs was used in order to limit the burden on the participants, since several other aspects (e.g., preferred type of supportive care, attitude towards self-management and eHealth) were assessed as well. Other studies mainly used the validated Supportive Care Needs Survey [18–21, 24, 26, 27], which was not yet available in Dutch at the time of this study.

Conclusion

Our study showed that supportive care needs including healthy lifestyle programs were prevalent among cancer survivors. In general, the attitude of cancer survivors towards self-management and eHealth was positive. Several sociodemographic and clinical variables and quality of life were found to be associated with perceived need for supportive care and attitude towards self-management and eHealth. Since the results showed differences in supportive care needs and attitude between cancer survivors, a tailored approach seems to be warranted to improve and innovate supportive care targeting cancer survivors.

References

Harrison JD, Young JM, Price MA, Butow PN, Solomon MJ (2009) What are the unmet supportive care needs of people with cancer? A systematic review. Support Care Cancer 17:1117–1128

Puts MTE, Papoutsis A, Springall E, Tourangeau AE (2012) A systematic review of unmet needs of newly diagnosed older cancer patients undergoing active cancer treatment. Support Care Cancer 20:1377–1394

Rabin C, Politi M (2010) Need for health behavior interventions for young adult cancer survivors. Am J Health Behav 34:70–76

McCorkle R, Ercolano E, Lazenby M, Schulman-Green D, Schilling LS, Lorig K et al (2011) Self-management: enabling and empowering patients living with cancer as a chronic illness. CA Cancer J Clin 61:50–62

Meropol NJ, Schulman KA (2007) Cost of cancer care: issues and implications. J Clin Oncol 25:180–186

Stitzenberg KB, Sigurdson ER, Egleston BL, Starkey RB, Meropol NJ (2009) Centralization of cancer surgery: implications for patient access to optimal care. J Clin Oncol 27:4671–4678

Schäfer W, Kroneman M, Boerma W, van den Berg M, Westert G, Devillé W, et al (2010) The Netherlands: Health Syst Rev 2010. Report No.: 12

Bright MA, Fleisher L, Thomsen C, Morra ME, Marcus A, Gehring W (2005) Exploring e-health usage and interest among cancer information service users: the need for personalized interactions and multiple channels remains. J Health Commun 10:35–52

Leykin Y, Thekdi SM, Shumay DM, Munoz RF, Riba M, Dunn LB (2012) Internet interventions for improving psychological well-being in psycho-oncology: review and recommendations. Psychooncology 21:1016–1025

Kuijpers W, Groen WG, Aaronson NK, van Harten WH (2013) A systematic review of web-based interventions for patient empowerment and physical activity in chronic diseases: relevance for cancer survivors. J Med Internet Res 15:e37

Emmons KM, Puleo E, Sprunck-Harrild K, Ford J, Ostroff JS, Hodgson D et al (2013) Partnership for health-2, a web-based versus print smoking cessation intervention for childhood and young adult cancer survivors: randomized comparative effectiveness study. J Med Internet Res 15:e218

Hong Y, Pena-Purcell NC, Ory MG (2012) Outcomes of online support and resources for cancer survivors: a systematic literature review. Patient Educ Couns 86:288–296

Schulman-Green D, Bradley EH, Knobf MT, Prigerson H, DiGiovanna MP, McCorkle R (2011) Self-management and transitions in women with advanced breast cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 42:517–525

Schulman-Green D, Bradley EH, Nicholson NRJ, George E, Indeck A, McCorkle R (2012) One step at a time: self-management and transitions among women with ovarian cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 39:354–360

Van Uden-Kraan CF, Drossaert CHC, Taal E, Smit WM, Bernelot Moens HJ, Van de Laar MAFJ (2011) Determinants of engagement in face-to-face and online patient support groups. J Med Internet Res 13:e106

van de Poll-Franse LV, van Eenbergen MCHJ (2008) Internet use by cancer survivors: current use and future wishes. Support Care Cancer 16:1189–1195

Bjoernes CD, Laursen BS, Delmar C, Cummings E, Nøhr C (2012) A dialogue-based web application enhances personalized access to healthcare professionals—an intervention study. BMC Med Informat Decis Making 12

Boyes AW, Girgis A, D’Este C, Zucca AC (2012) Prevalence and correlates of cancer survivors’ supportive care needs 6 months after diagnosis: a population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Cancer 12:150

Sanson-Fisher R, Girgis A, Boyes A, Bonevski B, Burton L, Cook P (2000) The unmet supportive care needs of patients with cancer. Cancer 88:226–237

Ream E, Quennell A, Fincham L, Faithfull S, Khoo V, Wilson-Barnett J et al (2008) Supportive care needs of men living with prostate cancer in England: a survey. Br J Cancer 98:1903–1909

Jorgensen ML, Young JM, Harrison JD, Solomon MJ (2012) Unmet supportive care needs in colorectal cancer: differences by age. Support Care Cancer 20:1275–1281

McIllmurray MB, Thomas C, Francis B, Morris S, Soothill K, Al-hamad A (2001) The psychosocial needs of cancer patients: findings from an observational study. European Journal of Cancer Care 10:261–269

Pauwels EJ, Charlier C, De Bourdeauhuij I, Lechner L, Van Hoof E (2013) Care needs after primary breast cancer treatment. Survivors’ associated sociodemographic and medical characteristics. Psycho-Oncology 22:125–132

Schmid-Büchi S, Halfens RJG, Müller M, Dassen T, van den Borne B (2013) Factors associated with supportive care needs of patients under treatment for breast cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs 17:22–29

Smith AB, King M, Butow P, Luckett T, Grimison P, Toner GC et al (2013) The prevalence and correlates of supportive care needs in testicular cancer survivors: a cross-sectional study. Psychooncology 22:2557–2564

Smith DP, Supramaniam R, King MT, Ward J, Berry M, Armstrong BK (2007) Age, health, and education determine supportive care needs of men younger than 70 years with prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 25:2560–2566

Brédart A, Kop JL, Griesser AC, Fiszer C, Zaman K, Panes-Ruedin B et al (2013) Assessment of needs, health-related quality of life, and satisfaction with care in breast cancer patients to better target supportive care. Annals of Oncology 24:2151–2158

Newell S, Sanson-Fisher RW, Girgis A, Ackland S (1999) The physical and psycho-social experiences of patients attending an outpatient medical oncology department: a cross-sectional study. Eur J Cancer Care 8:73–82

Ventura F, Öhlén J, Koinberg I (2013) An integrative review of supportive e-health programs in cancer care. Eur J Oncol Nurs 17:498–507

Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, de Bree R, Keizer AL, Houffelaar T, Cuijpers P, van der Linden MH et al (2009) Computerized prospective screening for high levels of emotional distress in head and neck cancer patients and referral rate to psychosocial care. Oral Oncol 45:e129–e133

Oskam IM, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, Aaronson NK, Witte BI, de Bree R, Doornaert P et al (2013) Prospective evaluation of health-related quality of life in long-term oral and oropharyngeal cancer survivors and the perceived need for supportive care. Oral Oncol 49:443–448

Lamers LM, Stalmeier PFM, McDonnell J, Krabbe PFM, van Busschbach JJ (2005) Measuring the quality of life in economic evaluations: the Dutch EQ-5D tariff. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 149:1574–1578

Verweij A (RIVM) Onderwijsdeelname: Indeling opleidingsniveau. Volksgezondheid Toekomst Verkenning, Nationaal Kompas Volksgezondheid Bilthoven: RIVM, 2008

Badr H, Chandra J, Paxton RJ, Ater JL, Urbauer D, Cruz CS et al (2013) Health-related quality of life, lifestyle behaviors, and intervention preferences of survivors of childhood cancer. J Cancer Surviv 7:523–534

Pekmezi DW, Demark-Wahnefried (2011) Updated evidence in support of diet and exercise interventions in cancer survivors. Acta Oncol 50:167–178

Ligibel J (2012) Lifestyle factors in cancer survivorship. J Clin Oncol 30:3697–3704

Poulsen GM, Pedersen LL, Østerlind K, Bæksgaard L, Andersen JR (2014) Randomized trial of the effects of individual nutritional counseling in cancer patients. Clinical Nutrition 33:749–753

Nekolaichuk CL, Turner J, Collie K, Cumming C, Stevenson A (2013) Cancer patients’ experiences of the early phase of individual counseling in an outpatient psycho-oncology setting. Qual Health Res 23:592–604

Wilhelmsen M, Lillevoll K, Beck Risør M, Ragnhild H, Johanson M, Waterloo K et al (2013) Motivation to persist with internet-based cognitive behavioural treatment using blended care: a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry 13:296

Ye J, Rust G, Fry-Johnson Y, Strothers H (2010) E-mail in patient-provider communication: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 80:266–273

van Gemert-Pijnen JEWC, Nijland N, van Limburg M, Ossebaard HC, Kelders SM, Eysenbach G et al (2011) A holistic framework to improve the uptake and impact of eHealth technologies. J Med Internet Res 13:e111

Peters TTA, van Dijk BAC, Roodenburg JLN, van der Laan BFAM, Halmos GB (2014) Relation between age, comorbidity, and complications in patients undergoing major surgery for head and neck cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 21:963–970

Kerr EA, Heisler M, Krein SL, Kabeto M, Langa KM, Weir D et al (2007) Beyond comorbidity counts: how do comorbidity type and severity influence diabetes patients’ treatment priorities and self-management? J Gen Intern Med 22:1635–1640

Børøsund E, Cvancarova M, Ekstedt M, Moore SM, Ruland CM (2013) How user characteristics affect use patterns in web-based illness management support for patients with breast and prostate cancer. J Med Internet Res 15:e34

van der Vaart R, van Deursen AJAM, Drossaert CHC, Taal E, van Dijk JAMG, van de Laar MAFJ (2011) Does the eHealth Literacy Scale (eHEALS) measure what it intends to measure? Validation of a Dutch version of the eHEALS in two adult populations. J Med Internet Res 13:e86

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Lonneke Gijsbers and Madeleine Wallien (Motivaction) for their contribution in drafting the study-specific questionnaires and in the data collection. This study is supported by a grant from Achmea Healthcare Foundation (SAG).

Conflict of interest

There was no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jansen, F., van Uden-Kraan, C.F., van Zwieten, V. et al. Cancer survivors’ perceived need for supportive care and their attitude towards self-management and eHealth. Support Care Cancer 23, 1679–1688 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2514-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2514-7