Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of basic trajectories in emotional adjustment in cancer survivors and identify predictors of long-term change.

Methods

We assessed 421 patients with cancer after diagnosis and 6 and 12 months later. Measures comprised anxiety, depression, perceived support, desired support, and illness intrusiveness.

Results

Anxiety decreased over time, whereas depression increased as did need for support. About one third of initial diagnostic classifications (into low distress, symptoms, or clinical level of distress) changed from one assessment to the next. Lower age and higher illness intrusiveness predicted which patient showed worse adjustment over time.

Conclusion

To avoid both over- and undertreatment of distressed individuals, repeated measurements are needed to identify actual adjustment trajectories. Initial assessment of emotional reaction to a diagnosis is not a reliable predictor of long-term adjustment. Patients should be made aware that completion of initial medical treatment even when accompanied by a positive prognosis does not in and of itself forecast how well patients adjust during survivorship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Rationale and objective

The majority of patients with cancer adjust well after receiving a diagnosis but a substantially large subgroup does not [1–3]. Estimates of the prevalence of anxiety and depression vary across studies but are notably higher when self-reported symptoms are used (typically in the 20–30 % range) relative to when actual diagnoses are obtained via gold standard-structured interviews (with rates closer to 10–15 %) [1].

Given improved cancer treatment outcomes overall, there is a steadily growing number of survivors. The emotional needs of these survivors change from diagnosis to treatment and, later, to survivorship-specific needs [4–6]. However, we have limited knowledge about the nature and determinants of emotional adjustment processes during survivorship. Especially at a time when health-care systems are trying to integrate survivor care into routine practice [6, 7], early identification of patient needs and corresponding care protocols are critical for (a) health-care planners to allocate supportive resources accordingly and (b) service providers to offer care and support in a tailored fashion.

The ideal study of long-term adjustment is expensive because of the necessary longitudinal approach and the need for large samples in order to capture varying demographics, cancer types and prognoses, and psychosocial environments. The most methodologically sophisticated studies on adjustment patterns or trajectories have used growth curve modeling to examine how many patterns of adjustment can be found in a set of longitudinal data. However, these growth curve studies on differential adjustment trajectories have limited generalizability because they only deal with breast cancer.

Given that 5-year survival is the longest, typically reported statistic for cancer prognosis [8], a follow-up of at least 5 year for emotional adjustment would seem ideal; however, this translates into expensive and difficult research. Too short a follow-up is also problematic because important changes in adjustment trajectories may be missed. A reasonable compromise is a follow-up length that likely includes a completed first wave of treatment as well as a period of survivorship that is no longer overshadowed by acute treatment and its side effects. Using only two time points, analyses are simple but only linear trends can be detected. There appears to be no consensus as to which protocol is most parsimonious, that is, the lowest number of measurement points still able to detect the most meaningful patterns of recovery. Cost and patient burden are of course natural limits to the search for increasingly fine-grained patterns.

Previous studies using growth curve analyses were useful in shaping the methodology for this study. When using an 8-month study window with four repeated measures of distress in patients with breast cancer, Lam and colleagues [9] observed four patterns with these population prevalence distributions: resilient (66 %), chronic distress (15 %), delayed recovery (7 %), and recovered (initially high distress, then a decline with a gradually flattening slope, 12 %). A study that followed a sample of patients with breast cancer over 55 months also revealed that a four-group “solution” best described the patterns of change: (a) initial slight elevation in distress, then a gradual decline to normal (12 %); (b) initially low distress, then rising and remaining stable and elevated (27 %); (c) starting moderately elevated and staying high (18 %); and (d) starting very high and staying high (43 %) [10]. A 5-year follow-up study in the UK with an impressively large sample (n = 2,208) confirmed that high anxiety and depression after diagnosis remained relatively stable, but a subgroup of initially well-adjusted patients worsened over time [11]. Lastly, using six measures of psychological well-being and an observation period of over 6 months, Dunn [12] classified four patterns of change in breast cancer patients: (a) starts low and declines further (39 %) and (b) starts slightly elevated and remains stable 45 %), as well as two “parabolic” groups: (c) starts slightly elevated, rises steeply, and fully returns 5 %) and (d) starts quite elevated, declines slightly, but rises back up again (11 %).

There is no singular explanation for why different studies reveal variation in patterns of recovery. It could be due to varying length of observation, differences in cancer type, and stage among samples being studied, varying numbers of repeated measures and/or their timing, the statistical approach, or any combination thereof. Furthermore, previous research has overwhelmingly focused on samples of breast cancer patients, and it is therefore unclear whether patterns of adjustment found in these studies will apply to patients with other cancer types. Therefore, take-home messages from trajectory studies for clinical practice are neither obvious nor simple.

When attempting to aggregate the results from the growth curve studies, it appears reasonable to conclude that if distress was measured only twice, four “core” patterns of change seem to exist [4] : (a) low distress at all times (“highly resilient”), (b) high distress at all times, (c) initially high then declining distress, and (d) initially low but then rising distress. This is likely and equally true for both anxiety and depression (given that they intercorrelate), although anxiety tends to change more quickly and is more situation-dependent [13, 14]. Therefore, synchronous changes in anxiety and depression should not be assumed. Throughout this paper, for the sake of parsimony, when broad term “distress” is used, it is meant to encompass depression and/or anxiety symptoms without assuming that one is a proxy for the other.

The “highly resilient” pattern describes patients who consistently show low distress throughout the entire process of diagnosis and treatment, and continuing into survivorship. This appears to be the most frequently occurring group, with a roughly 60–70 % prevalence. The remaining patterns are of approximately similar prevalence to each other. For clinical practice, this implies that a substantial subgroup of initially distressed patients does well on its own and may receive referrals they do not need, whereas a subgroup of initially nonsymptomatic patients worsens over time, and this turn for the worse will be missed unless patients are routinely reassessed or seek help on their own. The group that becomes worse might do so when they leave the relatively protective shell of intensive, specialized care and return to their family physicians and natural environment [4].

The previously described studies using growth curve analyses were ideal for testing theoretical models about differential underlying adjustment trajectories, but results do not readily translate into day-to-day clinical measurement practice. The current study was designed to identify and describe trajectories based on data routinely collected in clinical practice and that are easy to detect. Clinicians deal with individual patients and by necessity focus on meeting individuals’ needs. This raises the question of which data-analytical approach best meets the information needs of clinicians. When measures are repeated multiple times, many complex adjustment patterns may appear but it is doubtful that a growing number of identified patterns can be of incremental clinical use, even if such distinctions were statistically significant.

The specific objectives for this research were to (a) measure change and direction of change over a 1-year follow-up period and determine the prevalence of patients falling into meaningful levels of distress at each measurement point in a representative and mixed cancer sample; (b) study individuals’ shifting between diagnostic categories over time and report the prevalence of particular patterns of change in anxiety/depression; (c) using the simplest known four patterns of change that are also immediately meaningful to practitioners (high-to-high, low-low, high-low, and low-high distress), identify variables assessable at baseline (i.e., time of diagnosis) that are determinants of which patient follows which type of adjustment trajectory or pattern; and (d) use data from this longitudinal study to illustrate how different methods of describing and analyzing data serve as distinct “looking glasses” into the adjustment process.

Method

Participants

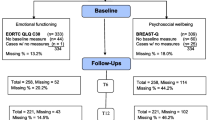

We consecutively identified and contacted 609 patients (the target had been N = 600) who met the initial criteria (legal age and first-time cancer). Of these, 423 patients met the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate. Patients were excluded if they were unable to consent or had English language skills judged too poor to benefit from professional services delivered in English. Study flow is shown in Fig. 1 and the sample is described in Table 1.

Procedure

Measures were taken at baseline (i.e., post-diagnosis but preceding treatment) and were repeated 6 and 12 months later; patients were recruited consecutively. Within a 6-month window post-diagnosis, patients have likely completed a first wave of medical treatment. Furthermore, a follow-up assessment was conducted at 12 months post-intake, a time point where patients typically no longer attend the specialty cancer clinic, may have returned to work, and are beginning to adjust to being a cancer survivor (unless they have moved to palliative care). Some additional measures were taken at 12 months only.

New patients begin their interaction with the provincial cancer care agency by attending a first consultation with the care team that typically lasts several hours. All patients (except those who are critically ill or with major language problems) complete the Psychosocial Screen for Cancer (PSSCAN), a validated screening tool that assesses symptoms of anxiety and depression, as well as perceived social support [15, 16].

For this study, patients visiting the cancer agency during the period of data collection received a brief letter of information about the study when they completed the PSSCAN and were asked whether a research assistant could contact them. When later contacted by telephone, they received a full explanation of the study and had an opportunity to ask questions. Patients interested in participating then received by mail one additional test (the Illness Intrusiveness Rating Scale [17] that they had not completed yet), the consent form, and a prestamped return envelope. This protocol presented a low burden because participants only needed to (a) complete one additional measure, (b) allow the researchers to recontact him/her by mail, with pre-stamped return envelopes after 6 and 12 months for additional completion of the questionnaire package (PSSCAN and the Illness Intrusiveness Rating Scale (IIRS)), and (c) allow the researchers to later merge the study data with other data on their medical status as entered into the provincial Cancer Agency’s Information System (CAIS), an electronic medical file. No additional visit to the cancer center was necessary for study participants.

Cancer type and absence/presence of metastases and demographic predictor variables were extracted from CAIS. At the 12-month follow-up, we also assessed whether patients had received psychosocial services. We computed a code for use in statistical analyses that incorporated the change in diagnostic category for the whole sample over time. Given that the development and validation work on PSSCAN had revealed meaningful cutoff scores (using computation of receiver operating characteristics (ROC)) and determinations of sensitivity/specificity [16], scores for anxiety and depression can be classified into three groups: low or “normal” scores, presence of symptoms, and clinical level (with cutoffs occurring at a score of 7 and below, 8–10 inclusive, and 11 or greater, respectively). The resulting groups had been referred to as “low,” “symptoms,” “high” in the original tool development manuscripts. For the next set of analyses, we dichotomized these groups by clustering the symptoms and the high group together and labelled these the high group to allow for simpler analyses with more even-sized samples relative to the low group.

In order to describe the patterns of change over the 1-year observation period, we then created four new groups labeled “low-low,” “low-high,” “high-high,” and “high-low” to describe change from baseline to 12-month follow-up. To illustrate this, a patient with a low-low anxiety pattern was defined as having a score of 7 or less at both times; by contrast, a patient described as low-high had an anxiety score of 7 or less at baseline but a score of 8 or more at 12-month follow-up. While crude, this categorization is easy to understand and use for clinical decision making.

Measures

Psychological distress

Distress was measured with PSSCAN [15, 18]. The 21-item PSSCAN assesses anxiety and depression, perceived social support, and desired social support. It has good psychometrics, including high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha averaging 0.83 and acceptable test-retest stability over 2 months (averaging r = 0.64)). Furthermore, PSSCAN subscales intercorrelate moderately to highly with instruments that measure the same constructs, demonstrating concurrent validity [15, 16]. Clinical validity was determined via computation of receiver-operating characteristics comparing the PSSCAN anxiety and depression subscales with the extensively validated Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [16, 17], and resulted in empirically justified cutoff scores for the presence of symptoms (subclinical) versus clinical levels of distress.

Illness intrusiveness

The IIRS is a measure designed to assess the impact of illness on various domains of functioning [19]. It taps disruptions in 13 life domains measured by one item each (e.g., “How much does your illness and/or your treatment interfere with your work?”). Internal consistency of the scale ranges from 0.80 to 0.94 for different diagnoses [19] and test-retest reliability ranges from 0.79 to 0.85. The IIRS also demonstrates a stable factor structure in medical and psychiatric patients [20].

Results

Sample information

The numbers of participants approached, those providing baseline and 6- and 12-month follow-up data, are shown in a flow chart (Fig. 1). In summary, n = 49 (21 %) were lost from baseline testing to 6-month follow-up (n = 7 had died) and n = 87 (26 %) were lost from baseline to 12-month follow-up, of whom n = 23 had died within this 1-year interval.

Demographics, disease characteristics, and psychological status at time of diagnosis (i.e., baseline) are described in Table 2. The distribution of cancer types in our sample is fairly representative of the local population [21]; 11 % had metastastic disease. Prostate cancer, on the other hand, is clearly underrepresented because prostate cancer patients are mostly treated by urologists outside of the cancer clinics. Data were not further broken down into disease stage because staging information is not equally relevant for all cancer types included here and, furthermore, many of the resulting data cells would have been too small for meaningful statistical analysis.

Summary of data-analytical approach

Descriptive statistics are offered for prevalence rates of psychological variables; change in psychological status was assessed via planned comparisons. Prevalence of patterns and within-patient shifts in diagnostic category were demonstrated via descriptive statistics. Variables that differ across the four trajectories were determined via one-way multivariate analyses of variance and post hoc test (Scheffe’s). The multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVAs) were preceded by conducting the Box’s M test to determine homogeneity of variance. Unfortunately, the Box’s M test for the analyses of the anxiety and the depression trajectory groups was significant and we used the conservative Pillai’s trace to evaluate the significance of the multivariate F [22, 23]. We further adopted a stringent p < 0.01 criterion for accepting significance of the multivariate F and applied the most conservative known type of post hoc tests: Scheffe’s.

Change in psychological well-being for the entire sample over time

Next, mean changes over time in perceived support (PS), anxiety (ANX), and depression (DEP) symptoms were computed, and inferential statistics (i.e., planned comparisons via dependent variable t tests) were calculated to study the extent of change. The means, resulting effect sizes, and significance of t test results are described in Table 2. As can be seen in Table 2, depression symptoms increased from baseline to 6-month follow-up and then leveled out. Anxiety symptoms declined steadily but only the difference between baseline score and 12-month follow-up scores was significant. Illness intrusiveness remained unchanged over the first half year but then declined, whereas perceived support remained extremely stable. Desired support, on the other hand, significantly increased over time.

The next step was the study of the differential trajectories or patterns. The low-low pattern appeared slightly more frequent for depression scores than for anxiety (64 vs 55 %). The high-low pattern seemed true more often for anxiety than for depression (17 vs 11 %), and a high-high trajectory was more than four times as prevalent for anxiety than for depression (18 vs 4 %). Lastly, a low-high pattern was twice as frequent for depression as for anxiety (20 vs 10 %). In summary, more than half of the patients fit the resilient category at all times but there was a trend for anxiety to wane, whereas depression symptoms were more likely to rise for a considerably sized subgroup.

Change in diagnostic category for each of the three categories as a function of category at baseline

We determined the percentages of patients belonging to each diagnostic category at 6 and 12 months as a function of which category they had belonged to at baseline. These computations revealed how many patients shifted a diagnostic category over time and the results are displayed in Table 3.

For both anxiety and depression, percentages of patients in the three diagnostic categories (low, symptoms, and high) at 6 and 12 months were similar. Further, it is evident that a large number of patients shifted in diagnostic categorization over the time period. For depression, about 40 % of initially high-scoring participants revealed lowered scores over time.

Characteristics (at baseline) of patients changing/not changing diagnostic recovery

The frequent shifts occurring over 1-year survivorship in diagnostic category for anxiety and depression raises the question of whether or not differential trajectories (i.e., stable low, stable high, increase/decrease) could have been predicted at baseline.

Evaluation of differential trajectories was addressed by conducting two multivariate F tests of mean group scores for the four groups of patients that reflect the low-low, low-high, high-high, and high-low patterns over time. One such MANOVA was conducted for the anxiety diagnostic groups, and a corresponding test was conducted for the depression diagnostic groups. Although anxiety and depression scores were strongly intercorrelated at both measurement points (r = 0.63 and r = 0.72 for 6 and 12 months, respectively), the change scores for anxiety and depression over 1 year correlated at a lower r = 0.49, therefore accounting for only 24 % of shared variance and necessitating independent analyses. Multivariate ANOVA was chosen because the hypothesized predictor variables (demographic, medical, psychological) are known to be intercorrelated, and MANOVA is a procedure that minimizes family-wise error. Post hoc tests were undertaken via Scheffé’s tests to assure a conservative approach when comparing all groups with each other. Results are shown in Tables 4 and 5.

Both multivariate F values were significant at p < 0.001 (true for Wilk’s lambda and Pillai’s trace alike), thus justifying simple effects and post hoc tests to further identify sources of variance. Predictably, baseline anxiety was a significant predictor in the MANOVA for the anxiety and the depression patterns; similarly, baseline depression predicted group membership for depression and anxiety. These results were not given further attention because each of these predictor variables had been used in defining the patterns of change in the first place.

The variables age and illness intrusiveness were significant predictors of patterns of change in anxiety. The stable, well-adjusted group (low-low) was older than the stable, poorly adjusted group (high-high, 63.9 vs 57.1 years). Both groups with high anxiety at baseline were younger than the other two groups. Illness intrusiveness scores were lowest in the low-low group (mean = 24.7) and highest in the high-high group (mean = 42.9), representing a difference of more than a standard deviation (d = 1.2). The high-low group could be differentiated at baseline from the group that remained highly anxious in that the high-low group was already less anxious at baseline. The variable metastasis (coded as yes/no) did not differentiate between groups.

For depression, age and illness intrusiveness were also significant predictors of patterns of change. The well-adjusted group (low-low) was older than the stable, poorly adjusted group (high-high, 63.7 vs 56.0 years). Illness intrusiveness scores were lowest in the low-low group (mean = 26.7) and far higher in the high-high group (mean = 39.5), representing a difference of almost a full standard deviation (d = 0.85). It is interesting that the high-low group could not be differentiated from the high-high group at baseline in that both revealed high levels of illness intrusiveness at baseline. The variable “metastasis” did not differentiate between groups.

Discussion

This study’s purpose was to explore data from a longitudinal study using routinely collected data and to provide a parsimonious description of change in patient well-being that may be directly relevant for the design of clinical care protocols and assessments. Results demonstrate what information can be gained when researchers go beyond group means to look at change in individuals, which is of course what clinicians do every day. We learned that many patients do not stay in their original diagnostic group (normal, symptoms, clinical) and that age and illness intrusiveness at baseline are the strongest predictors for subsequent change in levels of distress.

However, contrary to previous literature [3], metastatic status was not a significant predictor of group membership. This is probably not surprising given the loss of information inherent in coding metastasis as “yes” or “no” (which results in a very restricted range of scores) and also due to the fact that the size of the two cells was extremely uneven (approx. 10:1). Metastasis, of course, is a highly negative prognosticator, and patients with metastatic cancer at baseline will have passed away in disproportionate numbers by the time the 12-month follow-up was conducted. This in turn reduces the size of the subsample with metastasis that could be studied over time and reduces statistical power. To illustrate the degree to which metastatic status failed to have an impact, means for predictor variables at baseline were compared using t tests. Patients with metastases were not significantly different in terms of age, anxiety, depression, or illness intrusiveness at baseline (all p values >0.05).

Very much consistent with the literature was the observed deleterious effect of younger patient age on emotional adjustment [13, 14]. Similarly, illness intrusiveness at time of diagnosis was particularly powerful in predicting long-term emotional adjustment. We considered the possibility that illness intrusiveness was largely a proxy for disease progression. However, the mean scores for the IIRS in metastasized patients at baseline were not greater than for those with less advanced disease. It is therefore likely that illness intrusiveness does not arise exclusively due to the presence of physical symptoms, but predominantly reflects the subjective meaning of the overall diagnosis and the salience of symptoms for the individual patient.

All conclusions need to be interpreted in light of the study’s limitations. A 12-month follow-up is relatively short if the phenomenon of survivorship is to be studied. This time interval was chosen because during the 1 year post-diagnosis, the primary wave of treatment for most patients has been completed and patients are typically no longer seen at the specialty clinics. However, it would be simplistic and incorrect to state that at 12 months, all active treatment is complete because breast cancer patients and many patients with prostate cancer continue with hormone treatments for many years, and many patients may not yet consider themselves a survivor while on long-term hormone treatment. Nevertheless, follow-up assessments up to 6 years in length suggested that the adjustment trajectory seen at 1 year is a meaningful indicator of longer-term adjustment [24].

Unfortunately, our sample was not large enough to do justice to differences in adjustment trajectories that may be specific to tumor site and stage of progression. Given large differences in the prevalence of various cancer types and the fact that differential stages affect outcomes, only a very large sample would be both statistically powerful and representative. Just as the earliest studies in emotion trajectories were focused on breast cancer [e.g., 10] to get around this problem, future research on emotion change trajectories may need to tackle this issue one tumor group at a time, probably studying the more prevalent types (other than breast cancer) first.

The current study was not designed to settle the question how many distinct trajectory patterns there may ultimately be. Each statistical approach may lead to unique conclusions, and observed patterns of adjustment in one cancer type may not occur with similar prevalence in other cancer types. The planned emphasis here was on a simple, meaningful set of patterns that can be identified with a single repeated measure in a busy clinic and that, when observed, have obvious implications for clinicians and administrators. The chosen tool PSSCAN [15, 16] was designed and validated as a screening tool and, as the results here show, is also capable of detecting change in a repeated measures protocol. Nevertheless, PSSCAN is not held out to be equivalent to the gold standard of Structured Diagnostic Interviews.

Implications

These results have clear implications for designing survivorship care systems. First of all, there has to be at least one, preferably more, repeated assessment of psychological well-being to determine the patient’s trajectory of adjustment. Good time points for such a repeated measurement might be when a patient is transferred from the specialty clinic back to family physician care so that the community-based care provider has a roadmap for providing needed care and support [6]. Alternatively, the measures would be good to repeat when a patient has returned to a daily routine and has some appreciation for what their idiosyncratic survivorship is like.

Care providers can expect that anxiety will change independently from depression [13] and that support needs will go up, possibly because caregivers may show caregiving fatigue [25, 26] and/or the survivors miss the support they received in an acute care setting [4, 6].

References

Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, Halton M, Grassi L, Jahansen C, Meader N (2011) Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: a meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol 12:160–174

Stanton AL (2012) What happens now? Psychosocial care for cancer survivors after medical treatment completion. J Clin Oncol 2012(11):1215–1220

Vodermaier A, Linden W, McKenzie R, Greig D, Marshall C (2011) Post-diagnosis anxiety and depression: contribution of disease stage and cancer site in four common types of cancer. Br J Cancer 105:1814–1817

Henselmans I, Helgesen VS, Seltman H, de Vries J, Sanderman R, Ranchor AV (2010) Identification and prediction of distress trajectories in the first year after a breast cancer diagnosis. Health Psychol 29:160–168

White K, D’Abrew N, Katris P, O’Connor M, Emery I (2012) Mapping the psychosocial needs of cancer patients: findings from observational study. Eur J Cancer Care 21:107–116

Thorne S, Hislop TG, Kim-Sing C, Oglov V, Oliffe JL, Stajduhar KI (2014) Changing communication needs and preferences across the cancer care trajectory: insights from the patient perspective. Supp Cancer Care 22:1009–1015

Sabatino SA, Thompson TD, Smith JL, Rowland JH, Forsythe LP, Pollack L, Hawkins NA (2013) Receipt of cancer treatment summaries and follow-up instructions among adult cancer survivors: results from a national survey. J Cancer Surv 7:32–43

National Cancer Institute (2014) SEER mortality statistics. http://seer.cancer.gov/mortality. Accessed 10 Sep 2014

Lam WWT, Bonanno GA, Mancini AD, Ho S, Chan M, Hung WK, Or W, Fielding R (2010) Trajectories of psychological distress among Chinese women diagnosed with breast cancer. Psychol-Oncol 19:1044–1051

Helgeson VS, Snyder P, Seltman H (2004) Psychological and physical adjustment to breast cancer over 4 years: identifying distinct trajectories of change. Health Psychol 23:3–15

Hopwood P, Sumo G, Mills J, Haviland J, Bliss JM on behalf of the START Trials Management Group (2010) The course of anxiety and depression over 5 years of follow-up and risk factors in women with early breast cancer: results from the UK Standardization of Radiotherapy Trials (START). Breast 19:84–91

Dunn LB, Cooper BA, Neuhaus J, West C, Paul S, Aouizerat B, Abrams G, Edrington J, Hamolsky D, Miaskowski C (2011) Identification of distinct depressive symptom trajectories in women following surgery for breast cancer. Health Psychol 30:683–692

Carlson LE, Waller A, Groff SL, Giese-Davis J, Bultz BD (2013) What goes up does not always come down: patterns of distress, physical and psychosocial morbidity in people with cancer over 1 year period. Psycho-Oncology 22:168–171

Giese-Davis J, Waller A, Carlson LE, Groff S, Zhong L, Neri E, Bachor SM, Adamyk-Simpson J, Rancourt KMS, Dunlp B, Bultz BD (2012) Screening for distress, the 6th vital sign: common problems in cancer outpatients over 1 year in usual care; associations with marital status, sex and age. BMC Cancer 12:441

Linden W, Yi D, Barroetavena MC, MacKenzie R, Doll R (2005) Development and validation of a psychosocial screening instrument for cancer. Health Qual Life Outcome 3:54

Linden W, Vodermaier A, MacKenzie R, Barroetavena M, Yi D, Doll R (2009) The Psychosocial Screen for Cancer (PSSCAN): further validation and normative data. Health Qual Life Outcome 7:16

Devins GM (1994) Illness intrusiveness and the psychosocial impact of lifestyle disruptions in chronic life-threatening disease. Adv Renal Repl Ther 1:251–263

Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D (2002) The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res 52(2):69–77

Devins GM, Dion R, Pelletier LG, Shapiro CM, Abbey S, Raiz LR, Binik YM, McGowan P, Kutner NG, Beanlands H, Edworthy SM (2001) Structure of lifestyle disruptions in chronic disease: a confirmatory factor analysis of the illness intrusiveness scale. Med Care 39:1097–1104

Bieling PJ, Rowa K, Antony MM, Summerfeldt LJ, Swinson RP (2001) Factor structure of the Illness Intrusiveness Rating Scale in patients diagnosed with anxiety disorders. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 23:223–230

BC Cancer Agency Survival Statistics (2007) The surveillance and outcomes unit population oncology, 2010. http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/NR/rdonlyres/D8291ED8-FAEE-4692-A256-5320928187F2/44155/Survival_Statistics_2007_Rerun.pdf. Accessed 25 May 2012

Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS (2012) Using multivariate statistics, 6th edn. Pearson, Boston

Huberty CJ, Petoskey MD (2000) Multivariate analysis of variance and covariance. In: Tinsley H, Brown S (eds) Handbook of applied multivariate statistics and mathematical modeling. Academic, New York

Lam WWT, Shing YT, Bonanno GA, Mancini AD, Fielding R (2012) Distress trajectories at the first year diagnosis of breast cancer in relation to 6 years survivorship. Psychol-Oncol 2012(21):90–99

Ploos van Amstel FK, van den Beerg SW, van Laarhoven HWM, Gielissen MFM, Prins JB, Ottevanger PB (2013) Distress screening remain important during follow-up after primary breast cancer treatment. Supp Care Cancer 21:2107–2115

Dunn LB, Aouizerat BE, Cooper BA, Dodd M, Lee K, West C, Paul SM, Wara W, Swift P (2012) Trajectories of anxiety in oncology patients and family caregivers during and after radiation therapy. Eur J Oncol Nurs 16:1–9

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Colleen Wong, CHIM, from the BC Cancer Agency, Surveillance & Outcomes Unit—Population Oncology, for provision of the survival data. This study was supported by the Canadian Institute for Health Research (CIHR Team for Supportive Cancer Care; #AQC83559, PIs Richard Doll and Arminee Kazanjian).

Conflict of interest

There are no financial interests associated with this work, and none of the authors are in a conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Linden, W., MacKenzie, R., Rnic, K. et al. Emotional adjustment over 1 year post-diagnosis in patients with cancer: understanding and predicting adjustment trajectories. Support Care Cancer 23, 1391–1399 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2492-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2492-9