Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to cross-sectionally assess quality of life (QoL) in survivors of childhood Hodgkin's disease (HD) in a cohort treated for HD in the successive German–Austrian therapy studies HD-78, HD-82, HD-85, HD-87, HD-90, HD-95, respectively, in accordance with the HD-Interval-Treatment recommendation between 1978 and 2002.

Patients and methods

Data from QoL questionnaires were provided by 1,202 (66 %) of 1,819 invited survivors. These included the EORTC QLQ-C30 and socio-demographic variables. Data of a homogenous sub-sample (n = 725) defined by age (21–41 years) and event- free-survival (no progress, relapse or secondary malignancies) were compared to an age-adjusted German reference sample (n = 659).

Results

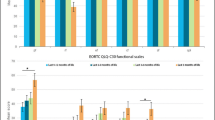

While the global and physical QoL scores were comparable to those of the general population, survivors' mean scores were more than 10 points lower on the EORTC QLQ-C30 scales “Emotional” and “Social Functioning”. On the symptom scales, higher mean scores, exceeding 10 points, were obtained for the scales “Fatigue” and “Sleep”. In general, there was a gender effect showing lower functioning and higher symptom levels in women, most prominently in the group of young women (21–25 years). The results within the group of HD survivors could not be associated with the time since treatment, the age of HD survivors at diagnosis or the extent of therapy burden.

Conclusion

Clinicians engaged in follow-up care should be sensitive to aspects of fatigue and related (emotional) symptoms in HD childhood cancer survivors and encourage their patients to seek further support if needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

While assessment of quality of life (QoL) is a well-established part of surveillance projects in long-term survivors of adult Hodgkin's disease (HD) in Europe [1–3], there is still a lack of systematic evaluation of QoL in corresponding survivors who were treated during childhood or adolescence. Simultaneously, due to continued excellence in treatment outcomes [4] (overall survival >95 %), a significant number of survivors of childhood HD are in long-term follow-up. Examination of long-term effects on QoL is of great relevance in this group, as the illness interrupted developmental stages and may have resulted in missed or delayed critical life milestones. Such studies can serve as a basis to develop or optimize appropriate interventions for survivors with impaired QoL and/or poor (psycho-) social outcomes [5].

Studies conducted in countries other than Germany, e.g. in the USA, within the framework of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS), provide broad insights into the general QoL status and related variables in childhood cancer survivors [6–9]. Other cohorts were obtained elsewhere in Europe [10, 11] and in Japan [12]. In general [9], survivors seem to have similar QoL levels when compared to siblings and/or population-based controls. Different findings exist primarily for survivors of CNS tumours and bone tumours. In addition, even if QoL itself was not impaired, variables which seem strongly associated with it (such as different indicators for psychosocial well-being) were partially impaired in these cohorts.

According to these inconsistent findings, authors of independent reviews emphasize that QoL results are not homogeneous and at times contradictory when comparing different investigations [7, 8]. There are also differing findings in survivors with different childhood cancer diagnoses: In one review [9], it is reported that long-term survivors of CNS tumours, lymphoma and bone and soft tissue sarcomas have the lowest QoL mean scores, while in another study [11], relevant mean differences in physical dimensions of QoL questionnaires were found only in survivors of CNS and bone tumours when compared to controls. A relatively homogenous finding seems to be that long-term survivors of childhood cancer show negative scores more often in physical than in emotional QoL domains [8].

In a published European study of adult HD patients, impaired QoL was reported in a subgroup of long-term survivors [1, 13]; increased fatigue levels were also reported. According to this, fatigue has emerged as an often-experienced disturbance of HD survivors after onset of disease in adulthood [2, 3] and was also examined in a large CCSS sample [14], revealing impaired scores especially for childhood HD survivors when compared to siblings.

Inconsistent findings are partly due to methodological issues and heterogeneous study aims, designs and employed instruments, thus further reducing the comparability of studies. QoL data may also vary according to cultural background and national health-care systems [9]. For a full understanding and valid interpretation of QoL results, the evaluation of scores in respect to clinical relevance is also a field of interest [15].

The aim of the presented project is a cross-sectional comprehensive evaluation and description of QoL in a large cohort of long-term survivors treated for HD in the successive German–Austrian therapy studies DAL-HD-78, HD-82, HD-85, HD-87, HD-90 (study centre in Münster) [16–19], GPOH-HD-95 [20] and according to the GPOH-HD-Interval-Treatment Guideline (study centre in Berlin-Buch) [21]. The results of the EORTC QLQ-C30 and socio-demographic variables are presented in comparison to reference data from the German population, representing a homogenous subgroup of participants aged 21 to 41 unaffected by a history of relapse (Fig. 1). We hypothesize that no meaningful differences between the HD survivors cohort and the reference group will be obtained in respect to the different dimensions of QoL. If, however, differences occur, it is hypothesized that HD survivors will be more impaired on those dimensions related to physical functioning. In order to analyse potential predictors of various impairment within the cohort of HD survivors, we explored differences related to time since diagnosis, age at diagnosis and therapy burden.

Methods

Patients

All patients enrolled are part of a cohort of paediatric patients, treated for HD and enrolled in the German–Austrian consecutive multicentre trials DAL-HD-78, HD-82, HD-85, HD-87, HD-90 and the European trial GPOH-HD-95. Additional patients were included who were treated according to the GPOH-HD-Interval-Treatment-Guideline. All listed trials were initiated under the auspices of the DAL and GPOH, respectively. As the numbers in the trial declaration indicate the starting year of the trial, patients were diagnosed and treated in the years between 1978 and 2002. The GPOH-HD-Interval-Treatment-Guideline ended in 2002. This treatment [21] was identical to the GPOH-HD-95 trial with the exception that all intermediate and advanced stage patients received radiation.

The characteristics of the different treatment regimens are described in detail in [16–20]. Therapy in the different trials has changed in respect to the amount of administered cycles of chemotherapy and radiotherapy doses. In the consecutive protocols, radiotherapy doses were decreased. Additionally, a more precise risk stratification was established. This is also reflected in the descriptive variable “therapy burden” (see below).

Patients were followed up by longitudinal surveillance examinations far into adulthood for documentation of late effects and final outcome [22–26]. Initially, 2,169 former patients from the abovementioned trials were eligible for the study. However, due to loss to follow-up, 1,819 German-speaking patients were finally asked to participate and to complete the questionnaire booklet. Of these 1,819 accessible, German-speaking survivors, 1,202 (66 %) sent back booklets and 617 (34 %) did not respond. Reminders were sent once.

For the current analyses, patients were excluded if they reported at least one event related to the treatment of HD, including progress, relapse and secondary malignant neoplasia. As socio-demographic information was obtained from self-reports only, patients younger than 21 years were analysed separately and were not included in this report. An overview of the remaining sub-sample including missing or incomplete data is presented in Fig. 1 (flow chart).

Treatment characteristics

To briefly summarize the treatment characteristics among the different trials, a descriptive variable “therapy burden” (TB): was created: This variable quantifies the amount of chemotherapy cycles (CCy) and radiotherapy doses. TB low = score 2, TB middle = score 3–8, TB high = score 9. These result from the addition of different scores for chemo- and radiotherapy: score 1 ≤20 Gy or ≤2 CCys, score 2 >20 ≤ 30 Gy or 4 CCys and score 3 >30 Gy or >4 CCys (Table 1). Due to further development in HD therapy, therapy burden decreased in later trials due to continuous reduction of radiotherapy doses respectively elimination of radiotherapy in the trials GPOH-HD-95 and HD-Interval in case of excellent response to chemotherapy.

Instruments

Assessment of socio-demographic characteristics

Standard socio-demographic data included information on education level, marital status and current occupation.

Assessment of quality of life

For QoL assessment, the validated German version of the EORTC QLQ-C30 was used [27]. The EORTC QLQ-C30 is a patient-based questionnaire for self-reporting QoL in adult cancer patients and consists of nine scales: five functioning scales (“Physical”, “Role”, “Cognitive”, “Emotional” and “Social Functioning”), three symptom scales (“Fatigue”, “Pain” and “Nausea and Vomiting”) and a global QoL scale. While these scales are multi-item, “Dyspnoea”, “Appetite Loss”, “Sleep”, “Constipation”, “Diarrhoea” and “Financial Difficulties” are assessed on a single item. Psychometric properties are well established and proven for many languages (cultures) including German [28]. Most items are answered using a Likert-type scale (answer format: not at all, a little, quite a bit, very much); the two global items are answered on a seven-point scale.

Corresponding scores are transformed to a 0–100 scale (scoring manual: [29]), 100 representing the highest functional and the highest symptom level, respectively. The EORTC QLQ-C30 has also been used in research in HD survivors after onset of disease in adulthood [1].

Procedures

The survey was conducted from 2005 to 2007. Written informed consent was given by patients and/or parents of patients, depending on age. The study received approval from the Ethical Committee at the Heinrich-Heine-University in Düsseldorf in 2005.

Controls

The sample of HD survivors was compared to an age-adjusted sub-sample of the German norm population (all participants included were between 21 and 41 years, n = 659) drawn from a major population-based, representative norm group (n = 2,037). These community data, including the EORTC QLQ-C30, were collected by way of face-to-face interviews in the year 1998. Individuals were sampled randomly via the Random Route technique (random selection of street, house, flat and target subject) in the household, based on 216 sample points [30]. The original norm data set was kindly provided by the investigators. To control for age effects, controls and survivors were stratified into four age groups (AG): AG 1 = 21–25 years, AG 2 = 26–30 years, AG 3 = 31–35 years and AG 4 = 36–41 years.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were generated for patients' characteristics and comparisons of HD survivors and controls. Dependent on item characteristics and distribution of data, χ 2 test, z tests (with Bonferroni adjustment) or t tests were computed to determine statistical significance. Mean scores, mean differences and standard deviations of survivors and controls in relevant EORTC QLQ-C30 functioning scales and symptom scales are presented separately for gender and age groups.

EORTC QLQ-C30 scores on functioning and symptom scales of HD survivors and controls were also compared using a three-factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA), employing the factors “category” (survivors vs. controls), “gender” and “age group”. This statistical method was chosen to avoid multiple comparisons of means.

To investigate if the results from the QoL scales within the group of HD survivors differ in regard to age at diagnosis, time since diagnosis and therapy burden, univariate regression and univariate logistic regression analysis, respectively, was used. Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS/version 20) was used for all analyses.

Results

Comparison of participants and non-responders

Before the evaluated sub-sample was created, participants who took part in the QoL study and non-responders (patients who failed to send back the completed questionnaire booklet) were compared: As far as information was available, participants (1,202) compared to non-responders (617) were older (mean/M = 26.17 years vs. mean/M = 23.58 years, p < 0.001) and more likely to be male (51.33 vs. 40.52 %, χ 2 [1, n = 1,819] = 19.11, p < 0.001). Most importantly, stage and dissemination of disease as well as treatment characteristics were not significantly different when comparing participants to non-responders.

Socio-demographic and disease-related characteristics

The final cohort consisted of 725 HD survivors and 659 controls. Disease-related characteristics of the 725 former patients are presented in Table 1. Treatment characteristics were summarized as a classification of “therapy burden” (Table 1).

Socio-demographic characteristics of HD survivors and controls are shown in Table 2. HD survivors differed from the general population in respect to all variables: HD survivors were on average 4 years younger. For example, female HD survivors were more likely to have completed a higher level of education than controls (χ 2 [1, n = 785] = 59.40, p < 0.001). There were also more HD survivors than controls who reported current enrollment in college, vocational or university education, and fewer HD survivors than controls were unemployed. All significant differences between HD survivors and controls are shown in Table 2.

Results of the EORTC QLQ-C30 functioning scales and the global QoL scale

Table 3 presents mean scores, standard deviations (SD) of all functioning scales in HD survivors and controls by gender, as well as mean differences per age group (AG 1 = 21–25 years, N = 266 (HD), N = 88 (C); AG 2 = 26–30 years, N = 224 (HD), N = 155 (C); AG 3 = 31–35 years, N = 141 (HD), N = 161 (C); AG 4 = 36–41 years, N = 99 (HD), N = 255 (C)). In general, higher scores reflect “better” functioning. The overall mean difference exceeded five points on the scales “Emotional Functioning” (EF), “Social Functioning” (SF) and “Cognitive Functioning” (CF). Depending on gender, the mean difference exceeded 10 points on the scales EF (women) and SF (men). For the scales “Physical Functioning” (PF), “Role Functioning” (RF) as well as on the global QoL scale, mean differences of less than 2.5 points were obtained.

Results of the EORTC QLQ-C30 symptom scales

HD survivors scored higher than controls on all symptom scales (see Table 4), reflecting higher symptom levels. This also held true for all one-item scales (data not shown, except for “Sleep”), in which mean differences stratified by gender were lower than 10 points (range between 1.5 and 9.5), except on the item “Sleep” (see Table 4) revealing an impairment on the same level as “Fatigue”. However, stratified by age group and gender, the largest mean differences occurred in young women on the symptom scale “Fatigue” and on the item “Sleep”.

ANOVAs

Three-way factorial ANOVAs were conducted, and results were determined for each functioning scale and the global QoL scale, as well as for the symptom scales and the item “Sleep” including the factors “category” (“HD survivors” vs. “controls”), “gender” and “age group” using the classification as described above. Significant (p < 0.001) main effects of “category” were found on every functioning scale but not on the global QoL scale. Results with higher effect sizes are described in the following. Effect sizes (eta-squared) higher than 0.035 were obtained on the scales EF: F [1, 1,384] = 54, 6, p < 0.001; partial eta-squared = 0.038; CF: F = 52, 1, p < 0.001; partial eta-squared = 0.037; SF: F = 64.4, p < 0.001; partial eta-squared = 0.045. In addition, significant (p < 0.001) main effects of “category” were found on the symptom scales “Fatigue”, “Pain”, as well as for the item “Sleep” but not for the symptom scale “Nausea and Vomiting”. Effect sizes (eta-squared) higher than 0.035 were obtained for the symptom scale “Fatigue” (F [1, 1,384] = 97, 4, p < 0.001; partial eta-squared = 0.066) and the item “Sleep” (F [1, 1,384] = 71, 7, p < 0.001; partial eta-squared = 0.050).

In addition, on a lower level of significance (p < 0.025), there were main effects of gender on nearly every functioning scale and symptom scale, consistently showing lower scores for women, as is generally well known in QoL investigations [28]. However, in our study, it was most pronounced in EF: F = 38.4, p < 0.001; partial eta-squared = 0.027.

One main effect of age occurred on the scale PF (F = 5, 5, p < 0.001; partial eta-squared = 0.012). No interaction effects between the different combinations of factors were observed.

Analysis in regard to age in the female subgroup

According to results shown in Tables 3 and 4, it seems remarkable that the youngest women (21–25 years) showed the highest or higher mean differences on most QoL scales compared to an age-adjusted reference group. Yet the impairment in subsequent female age groups was less consistent. Nevertheless, neither main effect of age group (with the exception above) nor tests for contrasts were statistically significant. Compared to a summarized age group of all other women (AG 2–4, 26–41 years), these patients were even more likely to be treated in later trials and thereby also more likely to have a low therapy burden (AG1 χ 2 [1, n = 391] = 39.14, p < 0.001).

To better characterize this group, different variables were examined in the youngest group of women as shown in Table 5, compared to the summarized group mentioned above. Although the level of education is not significantly different, more young women are unemployed when compared to the group of older women. In addition, young women were also less likely to be married than the older women.

The mean differences (HD survivors vs. controls) on the EORTC QLQ-C30 “Functioning Scales” are also shown descriptively, emphasizing that mean differences to controls are increased up to threefold in this group of young women.

Univariate (logistic) regression analyses

Univariate regression analyses were used to explain differences on the QoL scales within the group of HD survivors. The following independent variables were used as potential predictors of QoL results (each for every univariate regression analyses/scale): age at diagnosis and time since diagnosis. For the categorial variable “therapy burden”, univariate logistic regressions were conducted. Every category was dichotomized and dummy coded.

In general, (logistic) regression analyses have only been done for those scales where relevant statistical differences between the cohort of HD survivors and the reference group were present. As described above, these were the scales “EF”, “SF”, “CF”, “Fatigue” and the item “Sleep”. Both sexes were analysed separately.

Nevertheless, on all of these scales/items, the resulting univariate models showed a very poor overall-model fit for all of the independent variables. Each of the independent variables fails to improve the prediction of the scores in the different QoL dimensions. Significant beta-coefficients (p < 0.01) were not obtained. Therefore, additional multivariate models were not examined.

Discussion

The presented data were collected from, to our knowledge, one of the largest, well-defined and homogenous cohorts of childhood HD survivors worldwide. Overall, we found a fairly good appraisal of most of the QoL scales indicating good QoL in many life areas. In terms of effect sizes [31], cancer survivors differed considerably in their QoL from the general population in emotional, social and cognitive functioning; even larger differences were seen in fatigue and problems with sleep. These results did not correspond with our hypotheses, assuming that there are no differences between survivors and controls. In addition, these differences were less pronounced on scales related to physical functioning.

While the obtained gender effects follow the described differences between men and women in the literature, age was not a statistically significant factor for the explanation of differences in QoL results. Nevertheless, especially in the group of young women HD survivors, remarkable differences in comparison to older women were obtained. It is also noteworthy that this group is more often unemployed and to a greater extent still engaged in professional education. Additionally, controls are more likely to be married than HD survivors. Therefore, the results in this cross-sectional analysis may indicate a prolonged adolescence and a delayed development into adulthood. In addition, no interaction effect, e.g. between age and gender or category and gender, was observed during the ANOVAs.

In order to investigate whether, e.g. sub-groups of HD survivors with special attributes have a higher contribution to these results, we conducted further analyses indicating that age at diagnosis, time since diagnosis and the different manifestations of therapy burden are not associated with QoL in HD survivors. However, with the predictors tested, we were only able to account for some of the potentially relevant basic socio-demographic and treatment-related confounders. In particular, treatment could only be roughly assessed. We suggest that further studies include more detailed treatment characteristics as well as acute and late side effects.

The statistical-based effect sizes are partly congruent with considerations by King [15] who tried to determine clinically based interpretations. Those approaches are restricted in respect to general methodological aspects. In regard to our study, there is a further relevant limitation for interpretation in respect to King's considerations as we did not compare clinical samples but used a reference sample for comparison. From another point of view, it may be an argument that the obtained differences between HD survivors and a control group have a broader implication in this group especially as mean differences may carry more weight in our cohort of long-term survivors (time since disease on average 15.26 years).

However, the research to what extent statistical differences reflect also clinical relevant differences is still in progress, and interpretations remain not finally clear, especially in the context of long-term surveillance. Clinicians engaged in surveillance, and follow-up care may be well advised if they are sensitive to aspects of fatigue and related (emotional) symptoms in this group of childhood cancer survivors.

Comparing our data with other investigations of childhood cancer survivors, e.g. [8], it is interesting to note that physical or global domains of QoL are less affected. In contrast, our former patients present with larger impairments in psychosocial dimensions.

Our results concerning “Fatigue” from the EORTC QLQ-C30 are in line with cross-sectional results of HD survivors with disease onset in adulthood [2]: In our cohort, even after a longer (average) time since diagnosis, fatigue scores were increased. In a longitudinal study investigating adult early-stage HD patients, fatigue played a major role during and shortly after treatment but subsided over time in most patients, except in a high-risk group defined by high levels of end-of-treatment fatigue [1]. In contrast, patients with solid tumours experience fatigue over longer periods of time [32].

In a relevant segment of our childhood cancer survivors' cohort, fatigue remains a prominent QoL concern, even many years following treatment. Unfortunately, we do not have data on the fatigue levels immediately after end of therapy.

There are also results in a large CCSS sample [14], which showed more self-reported fatigue in survivors than controls. The authors noted that this holds true even if statistical significance may indicate spurious results considering the study's large sample sizes. The authors also point towards the relationship between fatigue and sleep disorders and revealed a significant association between fatigue, disordered sleep and daytime sleepiness both in survivors and controls. These findings are supported by our data with relevant differences between survivors and controls in problems with sleep and fatigue.

When we consider the socio-demographic patterns reported by HD survivors and controls, it is remarkable that HD survivors in general are more often engaged in college, vocational or university education and for the most part are less likely to be unemployed (except the young women): To some extent, this may reflect the lower mean age of HD survivors and also the different job-market situations at different time points of assessment (HD survivors were assessed nearly 10 years later than controls). In addition, the cross-sectional design of our study does not allow for statements if the survivors are still or no longer enrolled in professional education or will continue later in life. Nevertheless, it can be concluded that HD survivors seem to be well integrated into professional life. They seem to be on the right track to achieve professional milestones when compared to the general population as reflected in their qualifications of higher educational degrees. This is in line with more focused studies concerning social outcomes of childhood cancer survivors in general [33]. The authors of these studies propose that children treated for cancer in Germany are supported by a high level of psychosocial interventions and that these efforts contribute to improved social outcomes. These results underline national and cultural differences in social outcome.

Limitations

Apart from the problem of large sample sizes, which enhances the chance of detecting differences between groups, there are some additional important limitations in this investigation: Mean differences must also be interpreted in light of large standard deviations. Furthermore, control groups drawn from a general population have some overall critical aspects [13]: A reference group consisting of siblings of survivors, as used in nearly all references cited above, is more conservative, e.g. because baseline variables are more likely to be similar in siblings. Yet, the opposite may also be true: A reference group, which represents the general population, also incorporates participants, who suffer from chronic diseases or are themselves survivors of childhood cancer.

In addition, it is possible that the participating group of the HD survivors reflects a positive selection bias, meaning that the majority of those HD survivors who participated do not feel disturbed in their QoL and are socially well integrated. This is of certain importance considering the rate of participation.

Disregarding all these methodological pitfalls, the obtained results need further investigation, conducted ideally within longitudinal studies, which link more detailed treatment characteristics in clinical trials than used in our study directly to QoL assessment and also provide a long-term follow-up assessment including measurements of somatic late effects and coping styles. In addition, fatigue-specific questionnaires could help to gain detailed knowledge concerning the increased fatigue levels in these cohorts. This strategy allows for improving treatment as well as supporting strategies in more detail.

It is crucial that the comments concerning the clinical significance of results are supported by further intensive research, especially by studies which investigate factors potentially correlated with symptoms such as fatigue, and link them to the impairment of daily activities for childhood cancer survivors.

Even without these additional studies, there certainly are enough reasons to assume a good overall QoL and social integration in survivors of HD in childhood with the exceptions mentioned above. Accordingly, as already pointed out, clinicians engaged in surveillance and follow-up care should be sensitive to aspects of fatigue and related (emotional) symptoms in this group of childhood cancer survivors, and if needed should encourage them to seek further psychosocial support.

Abbreviations

- AG:

-

Age group

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- C:

-

Control group

- CCSS:

-

Childhood Cancer Survivor Study

- CCy:

-

Chemotherapy cycles

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- CF:

-

Cognitive functioning

- DAL:

-

German Working Group of Leukemia Research

- EF:

-

Emotional functioning

- Gy:

-

Gray

- GPOH:

-

German Society for Pediatric Hematology and Oncology

- HD:

-

Hodgkin's disease

- M:

-

Mean

- PF:

-

Physical functioning

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SF:

-

Social functioning

- RF:

-

Role functioning

- TB:

-

Therapy burden

References

Heutte N, Flechtner HH, Mounier N, Mellink WA, for the EORTC GELA H8 Trial Group et al (2009) Quality of life after successful treatment of early-stage Hodgkin's lymphoma: 10-year follow-up of the EORTC GELA H8 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 10:1160–1170

Rüffer JU, Flechtner H, Tralls P, for the German Hodgkin Lymphoma Study Group et al (2003) Fatigue in long-term survivors of Hodgkin's lymphoma: a report from the German Hodgkin Lymphoma Study Group (GHSG). Eur J Cancer 39:2179–2186

Flechtner H, Rüffer JU, Henry-Amar M et al (1998) Quality of life assessment in Hodgkin's disease: a new comprehensive approach: first experiences from the EORTC/GELA and GHSG trials. EORTC Lymphoma Cooperative Group. Groupe D’Etude des Lymphomes de L’Adulte and German Hodgkin Study Group. Ann Oncol 9(Suppl 5):147–154

Dörffel W, Körholz D (2010) Hodgkin's lymphoma. In: Estlin EJ, Gilbertson RJ, Wynn RF (eds) Pediatric hematology and oncology. Wiley-Blackwell, New York, pp 130–148

Stanton AL (2006) Psychosocial concerns and interventions for cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 24:5132–5137

Cantrell MA (2011) A narrative review summarizing the state of the evidence on the health-related quality of life among childhood cancer survivors. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 28:75–82

McDougall J, Tsonis M (2009) Quality of life in survivors of childhood cancer: a systematic review of the literature (2001–2008). Support Care Cancer 17:1231–1246

Zeltzer LK, Recklitis C, Buchbinder D, Zebrack B, Casillas J, Tsao JC, Lu Q, Krull K (2009) Psychological status in childhood cancer survivors: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol 27:2396–2404

Lund LW, Schmiegelow K, Rechnitzer C, Johansen C (2011) A systematic review of studies on psychosocial late effects of childhood cancer: structures of society and methodological pitfalls may challenge the conclusions. Pediatr Blood Cancer 56:532–543

Zeltzer LK, Lu Q, Leisenring W, Tsao JC, Recklitis C, Armstrong G, Mertens AC, Robison LL, Ness KK (2008) Psychosocial outcomes and health-related quality of life in adult childhood cancer survivors: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 17:435–446

Maunsell E, Pogany L, Barrera M et al (2006) Quality of life among long-term adolescent and adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol 24:2527–2535

Ishida Y, Honda M, Kamibeppu K et al (2011) Social outcomes and quality of life of childhood cancer survivors in Japan: a cross-sectional study on marriage, education, employment and health-related QOL (SF-36). Int J Hematol 93:633–644

Arden-Close E, Pacey A, Eiser C (2010) Health-related quality of life in survivors of lymphoma: a systematic review and methodological critique. Leuk Lymphoma 51:628–640

Mulrooney DA, Ness KK, Neglia JP et al (2008) Fatigue and sleep disturbance in adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS). Sleep 31:271–281

King MT (1996) The interpretation of scores from the EORTC quality of life questionnaire QLQ-C30. Qual Life Res 5:555–567

Brämswig JH, Hörnig-Franz I, Riepenhausen M et al (1990) The challenge of pediatric Hodgkin's disease: where is the balance between cure and long-term toxicity? A report of the West German multicenter studies DAL-HD-78, DAL-HD-82 and DAL-HD-85. Leuk Lymphoma 3:183–193

Schellong G, Hörnig-Franz I, Rath B et al (1994) Reducing radiation dosage to 20–30 Gy in combined chemo-/radiotherapy of Hodgkin's disease in childhood. A report of the cooperative DAL-HD-87 therapy study. Klin Padiatr 206:253–262

Schellong G (1996) Treatment of children and adolescents with Hodgkin's disease: the experience of the German–Austrian Paediatric Study Group. Baillieres Clin Haematol 9:619–634

Schellong G, Potter R, Brämswig J et al (1999) High cure rates and reduced long-term toxicity in pediatric Hodgkin's disease: the German–Austrian multicenter trial DAL-HD-90. The German–Austrian Pediatric Hodgkin's Disease Study Group. J Clin Oncol 17:3736–3744

Dörffel W, Lüders H, Rühl U et al (2003) Preliminary results of the multicenter trial GPOH-HD 95 for the treatment of Hodgkin's disease in children and adolescents: analysis and outlook. Klin Padiatr 215:139–145

Lüders H, Marciniak H, Rühl U et al (2011) Importance of prospective treatment planning by a reference center in pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma—a retrospective assessment of the HD-interval period following the trial GPOH-HD 95. Pediatr Blood Cancer 880 (abstr I-ISCAYAHL)

Brämswig JH, Heimes U, Heiermann E et al (1990) The effects of different cumulative doses of chemotherapy on testicular function. Results in 75 patients treated for Hodgkin's disease during childhood or adolescence. Cancer 65:1298–1302

Schellong G, Riepenhausen M, Creutzig U et al (1997) Low risk of secondary leukemias after chemotherapy without mechlorethamine in childhood Hodgkin's disease. German–Austrian Pediatric Hodgkin's Disease Group. J Clin Oncol 15:2247–2253

Schellong G, Riepenhausen M (2004) Late effects after therapy of Hodgkin's disease: update 2003/04 on overwhelming post-splenectomy infections and secondary malignancies. Klin Padiatr 216:364–369

Dörffel W, Riepenhausen M, Ludwig WD, Schellong G (2010) Langzeitfolgen nach Therapie eines Hodgkin-Lymphoms bei Kindern und Jugendlichen. J Onkologie 9:449–456

Schellong G, Riepenhausen M, Bruch C et al (2010) Late valvular and other cardiac diseases after different doses of mediastinal radiotherapy for Hodgkin disease in children and adolescents: report from the longitudinal GPOH follow-up project of the German-Austrian DAL-HD studies. Pediatr Blood Cancer 55:1145–1152

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B et al (1993) The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 85:365–376

Hjermstad MJ, Fayers PM, Bjordal K, Kaasa S (1998) Using reference data on quality of life—the importance of adjusting for age and gender, exemplified by the EORTC QLQ-C30 (+3). Eur J Cancer 34:1381–1389

Fayers P, Aaronson N, Bjordal K, Groenvold M, Curran D, Bottomley A (2001) EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual, 3rd edn. EORTC, Brüssel

Schwarz R, Hinz A (2001) Reference data for the quality of life questionnaire EORTC QLQ-C30 in the general German population. Eur J Cancer 37:1345–1351

Rost D (2005) Interpretation und Bewertung pädagogisch-psychologischer Studien. Beltz, Weinheim

Singer S, Kuhnt S, Zwerenz R et al (2011) Age- and sex-standardised prevalence rates of fatigue in a large hospital-based sample of cancer patients. Br J Cancer 105(3):445–451

Dieluweit U, Debatin KM, Grabow D et al (2010) Social outcomes of long-term survivors of adolescent cancer. Psychooncology 19:1277–1284

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to all participating survivors and/or parents as well as the data managers in this investigation, especially Angelika Görgen. This work was funded by a project grant of the German Childhood Cancer Trust (Deutsche Kinderkrebsstiftung), grant number: DKS 2005/04.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Calaminus, G., Dörffel, W., Baust, K. et al. Quality of life in long-term survivors following treatment for Hodgkin's disease during childhood and adolescence in the German multicentre studies between 1978 and 2002. Support Care Cancer 22, 1519–1529 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-013-2114-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-013-2114-y