Abstract

Purpose

We examined the health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and pain experiences of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and assessed content validity of existing patient-reported pain items for patients with HCC.

Methods

Semi-structured interviews to elicit symptoms, side effects and concerns were conducted with ten patients with HCC. Symptom and side effect importance was ranked on a 0 to 10 scale. Patients completed pain items from the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—Hepatocellular (FACT-Hep) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire—Hepatocellular-18 (EORTC QLQ-HCC18).

Results

Mean age was 58 years (range 33–77). Spontaneously reported symptoms included fatigue (n = 5), diarrhea (n = 5), skin toxicities (n = 5), and loss of appetite (n = 4). Upon questioning, nine of ten patients reported experiencing pain over the course of their treatment. Over half of the importance rankings given for pain were 8 or higher on a 0 to 10 scale. Abdomen (n = 7) and lower back (n = 3) were the most common sites of pain. Pain onset varied from 6 months pre-diagnosis to over 2 years post-diagnosis. All patients indicated that FACT-Hep and EORTC items adequately assessed their pain.

Conclusions

Results support the content validity of FACT-Hep pain items for patients with HCC. The finding that patients typically did not spontaneously report pain but often ranked it as very important for their HRQOL upon questioning suggests a need for systematic, routine pain and other symptom assessment and management as an integral component of patient care in advanced HCC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

The incidence and prevalence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) have increased in recent years, and it is currently the second leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide [1]. Viral infections from hepatitis B and C, as well as alcoholic cirrhosis represent key etiologies, with hepatitis C-viral infections predominating in the US and hepatitis B-viral infections in Asia and Africa [2, 3]. Despite published guidelines for surveillance of HCC, compliance with screening regimens is not consistent and about 80 % of patients with HCC present at advanced stages [4]. Treatment options for early disease include liver transplantation, and loco-regional therapies (trans-arterial chemoembolization [TACE], percutaneous ethanol injection [PEI], or (partial) surgical resection) [5]. Since most patients present with advanced, unresectable disease, loco-regional therapies remain the most widely used option. Following treatment with non-surgical loco-regional therapy, sorafenib is the most widely used systemic treatment [6].

Because of late stage diagnosis, co-morbid liver disease, and invasive loco-regional therapies, HCC likely has a significant impact on patient health-related quality of life (HRQOL). A number of scales have been developed to assess HRQOL in patients with HCC. The 18-item Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy — Hepatocellular (FACT-Hep) is a multi-dimensional instrument developed with patient and clinician input for use in all hepatobiliary cancers. Two additional scales include items from the FACT-Hep — the FACT-Hepatobiliary Symptom Index (FHSI-8), an abbreviated 8-item symptom index [7, 8], and the 18-item NCCN-Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy — Hepatobiliary–Pancreatic Symptom Index (NFHSI-18) [9]. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire—Hepatocellular-18 (EORTC QLQ-HCC18) [10] was also developed with input from patients and health care professionals. These scales include key symptoms for patients with HCC, such as weight loss, fatigue, and loss of appetite. Each scale also assesses patient pain. The FACT-Hep, FHSI-8 and NFHSI-18 each include three pain items — general pain, back pain and stomach/abdominal pain. The EORTC QLQ-HCC18 contains one abdominal pain item and one shoulder pain item. The inclusion of pain items is important for clinical care of patients with HCC as pain associated with cancer is often undertreated, due in part to poor assessment by clinicians and patients' reluctance to report it [11, 12]. Over two-thirds of patients with common solid tumors report pain; however, one-third of those with pain will not receive adequate analgesics [13]. Oncologists in the United States report poor assessment as the most important barrier to pain management [14]. Thus, valid patient-reported instruments which assess pain can facilitate pain assessment and management.

We sought to understand the salience of pain for HCC patients and place pain with the context of their HRQOL, including other symptoms, side effects, and concerns. In addition, as part of our ongoing work to develop a pain scale specific to HCC, we sought to assess the content validity of the pain items of the FACT-Hep and the EORTC among patients with HCC. These HRQOL scales have been demonstrated to be reliable and valid, to be internally consistent, and to be generally responsive in terms of measuring change over time [7, 15–17]. These HRQOL scales have also been extensively used in clinical studies [18–22]. However, although these scales have been derived with prior patient input, the FACT‐Hep included patients with other hepatobiliary cancers and may have over-captured content not specifically relevant to HCC. To address this possibility, we sought to identify those symptoms and pain concerns considered most important and relevant by patients specifically undergoing systemic treatment for HCC.

Methods

Patient eligibility and recruitment

Patients were recruited from the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University. Study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Northwestern University. Eligible patients were at least 18 years of age; English speaking; had a diagnosis of HCC; were currently or had previously received systemic therapy; and had performance status of ≤2. Patients were excluded from the study if they had previously undergone liver transplantation or had received local or loco-regional therapy (i.e., surgery, radiation therapy, hepatic arterial embolization, chemoembolization, radiofrequency ablation, PEI, or cryoablation) within 4 weeks of the study interview. Patients diagnosed with another cancer (except cervical carcinoma in situ, treated basal cell carcinoma, or superficial bladder tumors) were excluded unless cancer was curatively treated at least 3 years prior to study interview.

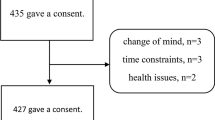

A member of the clinical team screened patients for eligibility. Eligible patients were approached by the study coordinator during a regularly scheduled clinic visit and invited to participate in a study interview. Patients who agreed to participate completed the study interview at that time, at a future appointment, or via the telephone. All participants provided informed consent prior to the study interview. Patients received a $50 gift card and a parking pass for their participation.

Interview procedures

After completing a brief sociodemographic questionnaire, patients participated in a 30- to 60-min semi-structured thematic interview led by a trained research interviewer. Individual interviews are well suited for research interested in uncovering participants' perspectives, experiences and the personal vocabulary used to describe complex constructs [23]. The interviewer began by obtaining diagnosis and treatment information from the patient. Next, the interviewer transitioned to a discussion of HRQOL: “We are interested in knowing about the side effects, symptoms, and/or concerns that you have or have had that are related to your cancer treatment and the impact of this treatment on your HRQOL. Please think of the full range of your experience receiving treatment for your cancer. Please tell me what you think are the most important symptoms of the illness, side effects of treatment, or other issues that may impact your quality of life.” Patients were asked to rank the importance of each issue on a 0–10 scale (0 = not at all important, 10 = extremely important). Following open-ended elicitation of QOL concerns, a series of questions guided patients through a discussion of pain related to their cancer or cancer treatment. If the patient had mentioned pain, they were asked to describe their cancer-related pain, followed by a series of probing questions (e.g., Where in your body have you experienced pain? When did you first start to experience the pain?). If the patient had not mentioned pain, the interviewer asked, “Has pain been an important concern for you?” If the respondent answered no, the interviewer asked whether they had experienced any pain. If the respondent answered yes, the interviewer asked them to describe their cancer-related pain, followed by the set of probing questions related to pain. Patients ranked the importance of each reported area of pain on a 0–10 scale (0 = not at all important, 10 = extremely important). Next, patients completed the pain-related questions from the FACT-Hep (“I have pain.” “I have pain in my back.” “I have discomfort or pain in my stomach.”) and the EORTC QLQ-HCC18 (“Have you had pain in your shoulder?” “Have you had abdominal pain?”). Finally, patients indicated whether FACT-Hep/EORTC questions addressed the type of pain they had experienced (yes/no) and whether there was anything missing from the questions (yes/no) and what, specifically, was missing. Interviews were audio-recorded. After the interview, key treatment and disease data were abstracted from the patient's medical record by a member of the study team and interview recordings were transcribed.

Analysis

Transcripts were reviewed by the first author and discussed with the study interviewer. Patient reports of the most important QOL and pain concerns and their rankings of those concerns were tabulated. Next, the first author reviewed comments about pain and constructed summaries of each patient's pain experience to include their reported areas of pain, rankings of importance of pain, and additional information such as patient statements about the causes or duration of the pain. The study team reviewed these summaries. Areas of ambiguity were addressed via further review of the interview transcripts and medical charts and the pain summaries were subsequently revised. The pain summaries were used to characterize the pain experiences of this sample of patients with HCC, including the most common areas of pain, patient rankings of the importance of the pain, and the duration, timing and cause of pain. The pain summaries were also "mapped" to the content to the FACT-Hep and the EORTC to assess the extent to which these sets of pain items captured the pain experiences of HCC patients receiving treatment.

Results

Twelve patients consented to participate in the study. Interviews were completed with nine men and one woman. Two additional patients consented at initial approach, but became too ill to complete the study interview. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. Mean age of the sample was 58 years (range 33–77). Six patients had co-morbid cirrhosis, and five had co-morbid hepatitis. Of these patients, four had both cirrhosis and hepatitis. Interviews were completed at an average of 11.7 months following diagnosis (range 1–32 months).

Quality of life concerns

Diarrhea, fatigue and skin toxicities were the most commonly mentioned quality of life concerns (Table 2). Loss of appetite, vomiting, and hair loss were also included as important concerns by more than one patient. A variety of other concerns (e.g., "knotty stomach," weakness, and dehydration) were mentioned but not by more than one patient. The concerns that were not mentioned by more than one patient varied considerably in importance — some concerns (e.g., knotty stomach, weakened intestinal tract, bloating, weakness, dehydration, and nausea) were ranked as extremely important. Others, such as voice change, were ranked as far less important.

Pain concerns: site of pain

When specifically asked if pain was an important concern, nine of the ten patients answered affirmatively. Table 3 lists the reported sites of pain mentioned by patients and their importance rankings. The abdomen was the most frequently mentioned site of pain. Other sites mentioned by multiple patients included the back, the liver area, and muscle cramping throughout the body. Ratings of the importance of each area of pain varied among patients. For example, the importance of abdominal pain ranged from 3 to 10 (mean 7.7) and the importance of back pain ranged from 0 to 9 (mean 7.0). Over half of the importance rankings given for pain were 8 or higher on the 0 to 10 scale.

Pain concerns: duration, timing and cause

Table 4 summarizes each patient's experience with respect to the site, duration, history/timing, and attributed (perceived) cause of pain. The abdomen, stomach and/or back emerged as sites of pain for eight of the nine patients (all except pt. 010) who reported pain. There was substantial variation in the timing of pain onset. The reported initiation of pain ranged from 6 months prior to diagnosis (pt. 009) to 2 ½ years post-diagnosis (pt. 007). The duration and perceived cause of pain also varied. Of the nine patients who reported pain, two patients (pts. 001, 006) experienced only temporary pain, which they attributed to chemoembolization. The other seven patients experienced some degree of ongoing pain, often in combination with transient pain. Five of the nine patients attributed their ongoing pain to specific causes, including ascites pressure (pts. 003, 008), metastases (pt. 007), and treatment (pts. 010, 011). Four of nine patients did not attribute a cause to their pain (pts. 003, 005, 008, 009). Several patients described the quality of life impact of their pain. For example, the liver pain following treatment reminded patient 001 that “I have liver cancer and half of (my liver) was taken out.” Several patients described the impact of stomach and abdominal pain, including negative impact on sleep (pt. 003), or feeling like you were going to "pop" if you stood up straight (pt. 006). Patient 005 described his stomach pain in this way, “Well, you can't bend over too well. You can't really lift anything… It kind of makes you not want to do anything.” For patient 009, stomach pain had a "terrible" impact on his life as is reduced his ability to walk and resulted in him spending more time in bed.

FACT-Hep and EORTC responses

Patient responses to the FACT-Hep and EORTC reflect both the content and the variation in pain experiences expressed in the patient interviews. Equal numbers of patients (n = 4) said they experienced no pain and "very much" pain in the last 7 days. When considering back pain, most patients (n = 7) indicated they had not experienced back pain in the last 7 days. Patients were least likely to report shoulder pain; eight of ten patients indicated that they had not experienced shoulder pain in the last week. The patient who reported experiencing "very much" shoulder pain had bone metastases identified in her leg, thus her shoulder pain may have been due to unidentified metastases. When asked whether the questions addressed the type of pain they experienced, all participants answered in the affirmative. The majority of patients stated that there was nothing missing from the pain questions. Two participants indicated that the questions were incomplete. These patients noted that other types of skeletal pain, skin pain and the mental toll of pain should be included. Other items that were noted as missing from the PRO questions were not explicitly linked to pain (i.e., intestinal problems and weight loss) (Table 5).

Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to characterize the manifestations and HRQOL impact of pain among advanced HCC patients and place pain in the context of other important and relevant symptoms. Following standard approaches, we elicited patient input via semi-structured interviews. In the initial, open-ended concept elicitation phase of the project, only one in ten patients spontaneously mentioned pain as an important concern. They described fatigue, diarrhea, appetite, and skin toxicity as important. Thus, we are confident that additional interviews would not alter this finding and we conclude that pain is not among the most salient HRQOL concerns for HCC patients receiving treatment. However, when asked about pain, nearly all (nine of ten) patients acknowledged pain or discomfort as a significant issue at some point in their treatment experience. The abdomen, stomach and/or back emerged as sites of pain for eight of the nine patients; this result supports the content validity of the FACT-Hep pain items. Subsequent, directed, probes focused on pain and the site, duration, timing and attributed causes of pain. We sought to include key clinical characteristics of the HCC patient population, for example, co-morbid cirrhosis and hepatitis. The sample included patients along the spectrum of treatment duration and receiving sorafenib, palliative, and experimental treatments. The inclusion of these key co-morbidities and a variety of treatment experiences is important to understanding the diverse experiences of the HCC population.

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. This is a relatively small sample of patients with HCC. Because pain was not spontaneously mentioned by patients, our pain data relied on the second-level interview data obtained from probes. Future studies with larger samples of patients with HCC might lead to better identification of temporal patterns of HCC pain. However, such work was beyond the scope of this study, which focused on HCC patient's pain experiences as part of an overall evaluation of key issues and assessed the validity of existing patient-reported pain measures among patients with HCC. Strengths of this study are our specific focus on the HCC population, while allowing diversity in inclusion criteria in terms of systemic sorafenib, post-sorafenib palliative care or experimental treatments. The sample included patients along the spectrum of disease and with a variety of co-morbid conditions, allowing potentially greater sensitivity to capturing symptoms and their unique manifestations across the treatment experience [24].

Several findings from this evaluation of important and relevant symptoms and concerns of patients with advanced HCC are noteworthy. First, as part of open-ended elicitation of the key issues, patients rated fatigue, diarrhea, skin toxicities and loss of appetite most often and as among the most important HRQOL concerns. Fatigue, loss of appetite, and diarrhea are symptoms that have been specifically endorsed as important in previous patient research underlying the development of HRQOL scales for hepatobiliary cancers. While skin toxicities was not specifically identified as a key issue previously and not included as a specific item in HRQOL scales, it is ostensibly accounted for by an item on side effects of treatment [7, 9, 25]. The prevalence and importance of skin toxicities is not surprising given that most patients in this study were on sorafenib, which in its pivotal clinical study in HCC was associated with a 21 % rate of hand–foot skin reaction, compared to only 3 % in the placebo group [26].

Second, as part of the focus of this study on assessment of pain, it became clear that while not a spontaneously raised leading concern, relevance of pain for patients undergoing systemic therapy for advanced HCC remains high. Patients frequently ranked the importance of their pain as 8 or higher on a 0 to 10 importance scale, where 10 indicated a concern was extremely important and several patients described significant functional limitations because of their pain. Confirmation of the relevance of pain in advanced HCC is an important finding, going beyond previous research in patients with diverse hepatobiliary cancers. The findings also re-affirmed that the stomach/abdomen and back were key sites of pain, consistent with pain questions in FACT-Hep. Notably, there was less support for the pain items from the EORTC as only one patient noted shoulder pain, and this pain may have been caused by metastases; eight of ten patients indicated no shoulder pain in the past week when completing the EORTC.

Third, our study findings can potentially inform the design of HCC clinical studies assessing potential benefits and adverse effects of drug interventions from the patient perspective as captured by available HRQOL scales. Symptom endpoints in HCC clinical studies, including the pivotal study for sorafenib, have not always been responsive to changes in radiologically measured disease [21, 27]. Arguably, measurement of change in symptom scales that included pain may have been confounded in HCC clinical studies by progression of underlying cirrhosis, which is not responsive to cancer treatment, or by side effects of treatment [28]. Indeed, our study showed that for some patients with HCC, abdominal pain in particular was associated with fluid retention, given that it resolved upon fluid drainage procedures. Patients not only differed in terms of whether the pain was transient or enduring, but also when it started in history of disease. Accordingly, our findings suggest that pain endpoints for clinical studies should be better informed by baseline patient pain. For example, pre-specified analyses could target endpoints reflecting improvement to those patients whose baseline symptoms, such as pain, are lasting and severe. Regardless, qualitative evidence from this study would suggest that an endpoint focused on pain content might, if suitably designed, be more aligned with changes in clinical status. Despite the heterogeneity of patient experiences with respect to the duration, timing and attribution of the cause of pain in the current sample, it was evident that the pain content of the FACT-Hep, the symptom-based FHSI-8 or the recent NFHSI-18, can adequately capture the most common pain experiences. Such cancer pain-focused symptom indexes, once further validated in quantitative and psychometric research, have the potential to offer brief, non-burdensome assessment in routine practice to guide pain-related care, and to permit pain-focused assessment of patients' self-reported pain status as an endpoint in clinical studies of new cancer treatments, within the context of multi-dimensional scales that also evaluate other important issues.

Fourth, our findings suggest a need for routine pain and other symptom assessment and management as an integral component of patient care in advanced HCC [28]. Cancer pain can lead to higher levels of patient distress [29], yet it can go unreported by patients who lack sufficient knowledge of the availability of effective pain interventions or who believe that it is not appropriate to speak with their clinicians about pain [30]. While cancer-related pain is widely experienced by patients, about half of patients feel that it is not considered a priority by their health care providers [30]. Patients interviewed for this study did not discuss pain until directly asked to within the interview, despite experiencing pain that often significantly impacted their lives. Anecdotal clinical evidence suggests patients may describe their pain, such as pressure from ascites, as discomfort. This pattern suggests that pain is not seen as a symptom or side effect in the same way as fatigue, or diarrhea. Our findings also highlight the difficulties of assessing and managing HCC pain in the clinical setting. These patients' pain experiences were complex in terms of timing, duration, and cause. Knowledge of timing, frequency, duration and treatment-relatedness of pain can improve communication of symptoms and expectations for pain relief between patients and providers.

References

Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D (2011) Global cancer statistics. CA: Cancer J Clin 61:69–90

Fattovich G, Stroffolini T, Zagni I, Donato F (2004) Hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: incidence and risk factors. Gastroenterology 127:S35–S50

Maluccio M, Covey A (2012) Recent progress in understanding, diagnosing, and treating hepatocellular carcinoma. CA Cancer J Clin 62:394–399

Qian Yy M, Yuwei JR, Angus P, Schelleman T, Johnson L, Gow P (2010) Efficacy and cost of a hepatocellular carcinoma screening program at an Australian teaching hospital. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 25:951–956

Bruix J, Sherman M (2011) Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology 53:1020–1022

Lang L (2008) FDA approves Sorafenib for patients with inoperable liver cancer. Gastroenterology 134:379

Yount S, Cella D, Webster K, Heffernan N, Chang C-H, Odom L, van Gool R (2002) Assessment of patient-reported clinical outcome in pancreatic and other hepatobiliary cancers: the FACT Hepatobiliary Symptom Index. J Pain Symptom Manag 24:32–44

Cella D, Paul D, Yount S, Winn R, Chang C, Banik D, Weeks J (2003) What are the most important symptom targets when treating advanced cancer?A survey of providers in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). Cancer Invest 21:526–535

Butt Z, Parikh ND, Beaumont JL, Rosenbloom SK, Syrjala KL, Abernethy AP, Benson AB, Cella D (2012) Development and validation of a symptom index for advanced hepatobiliary and pancreatic cancers. Cancer 118:5997–6004

Blazeby JM, Currie E, Zee BCY, Chie W-C, Poon RT, Garden OJ (2004) Development of a questionnaire module to supplement the EORTC QLQ-C30 to assess quality of life in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, the EORTC QLQ-HCC18. Eur J Cancer 40:2439–2444

Weiss SC, Emanuel LL, Fairclough DL, Emanuel EJ (2001) Understanding the experience of pain in terminally ill patients. Lancet 357:1311–1315

National Cancer Institute (2013) PDQ® Pain. http://cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/supportivecare/pain/HealthProfessional. Accessed 26 Feb 2013

Fisch MJ, Lee J-W, Weiss M, Wagner LI, Chang VT, Cella D, Manola JB, Minasian LM, McCaskill-Stevens W, Mendoza TR, Cleeland CS (2012) Prospective, observational study of pain and analgesic prescribing in medical oncology outpatients with breast, colorectal, lung, or prostate cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology

Breuer B, Fleishman SB, Cruciani RA, Portenoy RK (2011) Medical oncologists' attitudes and practice in cancer pain management: a national survey. J Clin Oncol 29:4769–4775

Sun VC-Y, Sarna L (2008) Symptom management in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin J Oncol Nurs 12:759–766

Steel J, Chopra K, Olek M, Carr B (2007) Health-related quality of life: hepatocellular carcinoma, chronic liver disease, and the general population. Qual Life Res 16:203–215

Cella D, Butt Z, Kindler H, Fuchs C, Bray S, Barlev A, Oglesby A (2012) Validity of the FACT Hepatobiliary (FACT-Hep) questionnaire for assessing disease-related symptoms and health-related quality of life in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. Qual Life Res 1–8

Tanabe G, Ueno S, Maemura M, Kihara K, Aoki D, Yoshidome S, Ogura Y, Hamanoue M, Aikou T (2001) Favorable quality of life after repeat hepatic resection for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology 48:506–510

Poon RFSYWLBCFWJ (2001) A prospective longitudinal study of quality of life after resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Arch Surg 136:693–699

Pistevou-Gombaki K, Eleftheriadis N, Plataniotis GA, Sofroniadis I, Kouloulias VE (2003) Octreotide for palliative treatment of hepatic metastases from non-neuroendocrine primary tumours: evaluation of quality of life using the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire. Palliat Med 17:257–262

Steel J, Baum A, Carr B (2004) Quality of life in patients diagnosed with primary hepatocellular carcinoma: hepatic arterial infusion of Cisplatin versus 90-Yttrium microspheres (Therasphere®). Psycho-Oncology 13:73–79

Brans B, Lambert B, De Beule E, De Winter F, Van Belle S, Van Vlierberghe H, de Hemptinne B, Dierckx R (2002) Quality of life assessment in radionuclide therapy: a feasibility study of the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire in palliative 131I-lipiodol therapy. Eur J Nucl Med 29:1374–1379

Weiss RS (1994) Learning from strangers: the art and method of qualitative interview studies. The Free Press, New York

Magasi S, Mallick R, Kaiser K, Patel JD, Lad T, Johnson ML, Kaplan EH, Cella D (2013) Importance and relevance of pulmonary symptoms among patients receiving second- and third-line treatment for advanced non–small-cell lung cancer: support for the content validity of the 4-item pulmonary symptom index. Clinical Lung Cancer 14:245–253

Heffernan N, Cella D, Webster K, Odom L, Martone M, Passik S, Bookbinder M, Fong Y, Jarnagin W, Blumgart L (2002) Measuring health-related quality of life in patients with hepatobiliary cancers: the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Hepatobiliary Questionnaire. J Clin Oncol 20:2229–2239

Llovet JM, Di Bisceglie AM, Bruix J, Kramer BS, Lencioni R, Zhu AX, Sherman M, Schwartz M, Lotze M, Talwalkar J, Gores GJ, Trials ftPoEiH-DC (2008) Design and endpoints of clinical trials in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 100:698–711

Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc J-F, de Oliveira AC, Santoro A, Raoul J-L, Forner A, Schwartz M, Porta C, Zeuzem S, Bolondi L, Greten TF, Galle PR, Seitz J-F, Borbath I, Häussinger D, Giannaris T, Shan M, Moscovici M, Voliotis D, Bruix J (2008) Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 359:378–390

Ingham J, Portenoy R (1996) Symptom assessment. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 10:21–39

Yamagishi A, Morita T, Miyashita M, Kimura F (2009) Symptom prevalence and longitudinal follow-up in cancer outpatients receiving chemotherapy. J Pain and Symptom Manag 37:823–830

Breivik H, Cherny N, Collett B, de Conno F, Filbet M, Foubert AJ, Cohen R, Dow L (2009) Cancer-related pain: a pan-European survey of prevalence, treatment, and patient attitudes. Ann Oncol 20:1420–1433

Conflict of interest

Support for this project was provided by Daiichi Sankyo Inc. Drs. Kaiser and Butt have received research funding from Daiichi Sankyo, Inc. Dr. Cella has received research funding and has a consultant relationship with Daiichi Sankyo. Dr. Mallick was employed by Daiichi Sankyo, Inc. during this project. Dr. Benson has a consultant relationship and is funded by Bayer/Onyx. Dr. Mulcahy has a consultant role with Bayer Onyx. Data are co-owned by Northwestern University and Daiichi Sankyo, Inc. and may be made available upon request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kaiser, K., Mallick, R., Butt, Z. et al. Important and relevant symptoms including pain concerns in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): a patient interview study. Support Care Cancer 22, 919–926 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-013-2039-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-013-2039-5