Abstract

Purpose

This study investigated satisfaction with treatment decision (SWTD), decision-making preferences (DMP), and main treatment goals, as well as evaluated factors that predict SWTD, in patients receiving palliative cancer treatment at a Swiss oncology network.

Patients and methods

Patients receiving a new line of palliative treatment completed a questionnaire 4–6 weeks after the treatment decision. Patient questionnaires were used to collect data on sociodemographics, SWTD (primary outcome measure), main treatment goal, DMP, health locus of control (HLoC), and several quality of life (QoL) domains. Predictors of SWTD (6 = worst; 30 = best) were evaluated by uni- and multivariate regression models.

Results

Of 480 participating patients in eight hospitals and two private practices, 445 completed all questions regarding the primary outcome measure. Forty-five percent of patients preferred shared, while 44 % preferred doctor-directed, decision-making. Median duration of consultation was 30 (range: 10–200) minutes. Overall, 73 % of patients reported high SWTD (≥24 points). In the univariate analyses, global and physical QoL, performance status, treatment goal, HLoC, prognosis, and duration of consultation were significant predictors of SWTD. In the multivariate analysis, the only significant predictor of SWTD was duration of consultation (p = 0.01). Most patients indicated hope for improvement (46 %), followed by hope for longer life (26 %) and better quality of life (23 %), as their main treatment goal.

Conclusion

Our results indicate that high SWTD can be achieved in most patients with a 30-min consultation. Determining the patient’s main treatment goal and DMP adds important information that should be considered before discussing a new line of palliative treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Medical end-of-life decisions are among the most difficult decisions for an individual to make. A patient’s satisfaction with the way that treatment-related end-of-life decisions are taken is highly determined by the communications skills of the physician [1–4].

Only few decades ago the decision-making process was not even a matter of debate between the patient and his treating physician. Current communication strategies involve patients and relatives to a maximal extent into medical decision-making. Asked about their preferences for decision involvement, an equal proportion of patients with advanced colorectal cancer wanted to share decision-making or wanted their doctor to lead [5]. In contrast, women with early breast cancer prefer a higher level of involvement in treatment decisions [6].

To enable patients to make an informed treatment decision, extensive information on prognosis, treatment options, adverse effects, and quality of life are necessary. Patients’ understanding that chemotherapy can cure a cancer in a palliative setting was surprisingly high, meaning that the standard for an informed consent to principle treatment goals was not met [7]. Two systemic reviews indicate that the use of decision aid tools result in higher patient knowledge and more active participation in decision-making but has no effect on patient satisfaction [8–10].Currently, the paradigm of goal-oriented patient care is predominant [11]. This patient-centered care model taking into consideration patients’ preferences and values demands better and more intensive doctor–patient communication [12].

Communication training programs, therefore, focus on patient-centered communication aimed at identifying individual patient preferences, needs, and values [11, 13, 14]. Identifying the goals of a new treatment ideally involves a two-step decision-making process [15], with (a) the physician explaining the medical issues and (b) the patient stating his/her values and preferences [16]. However, measuring the success of a patient–doctor encounter is an extremely challenging task mainly because it can be attributed not only to hard endpoints, such as the clinical treatment outcome, but also to several soft endpoints, such as personal preferences and expectations [17]. A commonly used surrogate to measure a patient’s perception of the encounter is “satisfaction with treatment decision” (SWTD), for which standardized scales exist [18].

We conducted a study to collect information on patient SWTD in patients undergoing palliative cancer therapy. The primary objectives of this study were to evaluate overall SWTD and to define factors that influence SWTD in this setting. Further objectives were to explore the decision-making process and patient preferences with regards to the decision-making model and the main goal of palliative treatment.

Patients and methods

In this cross-sectional survey, the 10 participating sites included a breast cancer center and a tertiary cancer center in the midsize Swiss city of St. Gallen, six affiliated hospitals, and two private oncology practices, all located in northeast Switzerland. Twenty medical oncologists were involved in the trial. Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review board of the Kanton St. Gallen.

All consecutive patients were invited to participate in the study while attending an outpatient visit 3 to 4 weeks after the start of a new line of palliative treatment (e.g., chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and hormonal treatment). All patients who were willing to complete a comprehensive questionnaire and had sufficient understanding of the German language were included. Oncology nurses provided and collected the questionnaires, while the treating oncologists were not involved in the patient data collection in order to avoid bias.

The patient questionnaire included the assessment of SWTD (satisfaction with decision scale) [18], DMP (control preference scale) [19], and subjective treatment goals, as well as basic sociodemographic information, further psychosocial parameters such as health locus of control (HLoC) [KKG “Kontrollüberzeugungen zu Krankheit und Gesundheit” scale validated for use in German-speaking population and defined as the belief that one’s own health status is determined by one’s own personal actions, rather than the actions of powerful others, e.g., health care professionals, or fate, luck, or chance] [20, 21], and several global quality of life (QoL) domains (linear analogue self-assessment [LASA] indicators) [22–24].The SWTD, DMP, HLoC, and QoL scales are validated measures used in the setting of advanced cancer [5, 25, 26]. Subjective treatment goals were addressed by an ad hoc question constructed for the purpose of this study. Patients were asked to identify their main treatment goal by choosing one of four possible answers (i.e., less symptom burden, hope for feeling better, prolongation of life, and better quality of life). Data regarding diagnosis, line of therapy, localization of metastases, expected prognosis, performance status, and duration of consultation for each patient were collected via a physician questionnaire.

Statistical analysis

Initial sample size calculations were based on SWTD as the primary outcome measure; 415 evaluable patients were required to achieve 80 % power in a multivariate model to detect an R-squared of 0.05 attributed to 20 independent variables using an F test with a significance level (alpha) of 0.05 [27].

Statistical analyses were descriptive and exploratory in nature. For the primary analysis, only patients completing all six relevant questions regarding SWTD were considered (evaluable analysis set, EAS). In the absence of an established cutoff for the satisfaction with decision total score (six items with five answer categories covering 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree (0); score range 5–30), we decided to use a pragmatic approach by considering the average of four points over the six questions as a reasonable cutoff. Therefore, scores of 24 or above were considered as high and scores below 24 as low SWTD. Cronbach’s alpha [28] was used to assess the internal consistency of the test score for this outcome variable. For the uni- and multivariate analyses to predict SWTD, only the patients with fully completed questionnaires were considered (sensitivity analysis set, SAS). Multiple imputation using 20 imputations and quantile regression were performed [29] as sensitivity analyses.

For the analysis of secondary variables, all available data were used (full analysis set, FAS). Groups were compared using Fisher’s exact test or chi-squared test for categorical data and Wilcoxon’s rank sum test or the Kruskall–Wallis test for continuous data. Consistency between DMP and the actual decision-making was assessed using Cohen’s kappa coefficient [30]. For the analysis of the questions assessing subjective treatment goals, it was decided to combine two of the possible answers, ‘less symptom burden’ and ‘hope for feeling better,’ into a single category ‘hope for improvement.’ P values were two-sided, not adjusted for multiple testing, and considered significant if <0.05. All analyses were performed using the R statistical software package (www.r-project.org) version 2.14.2 or later.

Results

Patient demographics and characteristics, and consultation setting

Four hundred eighty patients were enrolled between February 2009 and April 2011 (FAS) and 445 completed all six questions regarding the primary outcome measure (EAS). Fully completed questionnaires were available from 267 patients (SAS, Fig. 1). These were evaluated in the uni- and multivariate models of the primary analysis. The low number of complete questionnaires reduced the intended power of 80 %. Patient and site characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Satisfaction with treatment decision

Overall, 326 patients (73 %) reported high SWTD (≥24 points), with 82 patients (18 %) achieving the maximum score of 30 points. Accordingly, the summary scores for SWTD had peaks at 24 points and 30 points. There were no differences in the main sociodemographics between the patients with high satisfaction and those with low satisfaction.

Predictors of satisfaction with treatment decision

Several of the self-reported variables and disease characteristics were significantly associated with SWTD in the univariate analysis (Table 2). The following covariables were not significant: age, gender, marital/relationship status, religion, prognosis (>12 months vs. <6 months), treatment goal hope for improvement vs. longer life, decision-making preference (DMP), actual decision-making patient-directed vs. shared decision, KPS (70 vs. 50 or 60), treatment line, primary tumor site, external control by chance or fate, and use of complementary medication.

Subjective health status, consultation time, internal HLoC, family status, and physical well-being were chosen for fitting a multivariate model with SWTD as dependent variable. Only duration of consultation remained a significant predictor for SWTD in a multivariate analysis (coefficient 0.02; 95 % CI 0.00: 0.04; p = 0.02). This was confirmed in two sensitivity analyses as follows: a coefficient of 0.01 (95 % CI 0.00: 0.03, p = 0.06) based on 20 multiple imputations and a coefficient of 0.02 (95 % CI 0.01: 0.03, p = 0.02) in quantile regression.

Decision-making preference

On the control preference scale, patients were asked to state how they preferred to make the treatment decision and to indicate how the decision was actually made. Of the 463 patients who answered this question, 210 (45 %) preferred shared, and 203 (44 %) preferred doctor-directed, decision-making. Patient-directed decision was preferred by only 50 patients (11 %). Table 3 shows the degree of agreement between patients’ DMP and the perceived actual decision-making. The actual decision-making was consistent with the indicated preference in 328 patients (71 %) [Cohen’s kappa = 0.512], as indicated by the shaded fields in Table 3. Of these 328 patients, 223 (68 %) reported high satisfaction with their decision. DMP and actual decision-making were inconsistent in 135 (29 %) of patients, but again, 102 (76 %) of these patients reported high satisfaction with their decision. Agreement between preferred and actual decision-making was not significantly associated with SWTD (p = 1). However, among the 50 patients who preferred a patient-directed decision, 38 (76 %) reported high, and 11 (22 %) reported low (score < 24), satisfaction with their decision. Three variables were significantly associated with DMP as follows: geographic location of oncology site (p = 0.04) and KPS (p = 0.04), and treatment line (p = 0.01). Patients in a tertiary cancer center setting seemed to prefer shared decision-making compared to patients in a rural environment, in which the doctor-directed decision-making is rather dominant. In the group of patients with a poor KPS, doctor-directed decision is clearly favored over other models of decision-making, whereas patients with very good KPS prefer a shared decision. Patients with very advanced disease who received at least three treatment lines preferred doctor-directed decision or shared decision (Table 4).

Subjective treatment goals

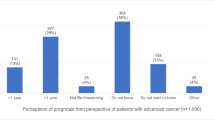

Almost half of the patients (46 %) indicated hope for improvement as their primary treatment goal. Living longer was stated by 26 % of the patients and better QoL by 23 %, respectively, with 5 % missing statements.

Health locus of control

Scores for the three HLoC subscales, internal control (i.e., residing in the person’s own actions), external control by actions of powerful others (e.g., health care professionals), and external control by chance or fate, were transformed based on normative data (i.e., a random sample of the general population) into average, below average, or above average scores. The majority of patients had average (n = 287; 60 %) or below average (n = 131; 27 %) scores in internal HLoC.

Scores for external HLoC by powerful others were average in 217 (45 %) and above average in 228 patients (48 %), while scores for external HLoC by chance or fate were average in 230 (48 %) and above average in 195 patients (41 %), regardless of whether they had high or low SWTD. This indicates that patients tend to have the belief that their health is externally determined, rather than controlled by their own actions.

Quality of life indicators

Individual scores for QoL indicators during palliative treatment varied considerably. Median overall QoL score was 67, median physical well-being score was 64, and median subjective health status score was 55 (for all three indicators as follows: min 0; max 100; higher scores reflect better condition), representing a rather impaired QoL (scores < 75) (Fig. 2). Median treatment burden was 34.5 (min 0; max 100, higher scores represent worse condition), indicating that the majority of patients were slightly (scores < 25) or moderately bothered by treatment-related difficulties, with a minority feeling considerably impaired (scores > 75).

Discussion

Treatment decisions in palliative cancer care depend on various patient-, treatment-, and disease-related factors. This study investigated patients’ SWTD and its predictors, as well as DMP and main treatment goals in the setting of an oncology network, consisting of a tertiary cancer center with affiliated rural oncology services. Most studies described in the literature were single-center studies, whereas our study describes a multi-institutional setting, with a large sample of patients (n = 480). Hence, our data are likely representative for a general clinical practice modality.

SWTD as the primary outcome was generally high in our sample of patients with advanced cancer treated in the oncology network. While univariate analyses revealed several factors to be significantly associated with SWTD, consultation time remained the only predictor of SWTD in multivariate analysis. The doctor–patient encounter, where patients were informed regarding a palliative treatment and asked to come to a final decision, lasted a median of 30 min. Consultation length varies between countries. In Switzerland, an average of 15 min is general practice [31]. Within a real-life setting at a busy outpatient clinic, half an hour to inform the patient and discuss palliative treatment options seems a reasonable and achievable time burden.

Unlike most trials, our study did not assess SWTD directly after the decision-making process, but 3–4 weeks after the start of the new treatment. At this point, patients had already acquired personal experience with the treatment of choice. Fear of anticipated adverse effects or a wave of optimism may influence the personal attitude on SWTD immediately after the consultation. This emotional bias was excluded by interviewing the patient later in the course of treatment. Reasoning and reflecting a treatment decision might foster inner poise or allow reframing. Therefore, this time point was chosen to capture a response shift of internal criteria, values, and preferences [32].

The overall score of SWTD reflects different aspects of satisfaction, such as patient satisfaction with information provision and treatment effects as well as emotional aspects of communication. Nevertheless, the doctor–patient encounter remains mainly a “black box,” not knowing the details of the information given. In this context, patients’ misunderstanding of given information or denial of the tumor situation could also not be explored. However, patient’s perception of information and communication may be more important for the evaluation of satisfaction than the actual communication [33, 34].

Shared decision-making is currently the most prominent model for doctor–patient interaction [35]. DMP commonly depends on age and cancer type. Elderly patients tend to prefer doctor-directed decision models [36, 37]. Breast cancer patients have a strong desire to be involved in treatment decisions [38] and shared decision-making was associated with improved short-term satisfaction in older breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant treatment [39]. In our study, an equal number of patients indicated doctor-directed decision and shared decision, respectively, as their DMP, and over 70 % of patients indicated that the way the actual decision was made was consistent with their DMP. A study with breast cancer patients in a curative setting reported patient–physician concordance on the decision-making model in only 42 % of patients [40], reflecting that patients in an adjuvant or curative treatment situation have different needs with respect to the treatment decision process than patients with advanced disease. The results of our study are in line with this conclusion. Patients who had a poor KPS or had received more than three treatment lines (representing advanced disease) prefer more often doctor-directed decision or shared-decision compared to patients with better KPS and fewer treatment lines.

The high degree of consistency between preferred and actual decision-making may explain the high SWTD observed in our study. As shown by Gattellari et al., satisfaction with the consultation was predicted by the patients’ perceived role in the decision-making process, irrespective of their preferred role [41].

In our study, all physicians involved in the decision-making process were trained to respect patients’ values and preferences [12].Communication styles and wording regarding patient information on treatment-related adverse events, prognosis, and the aim of treatment given during the decision-making process were not harmonized or standardized in any way, again in order to reflect daily practice. It is well known that physicians trained in communication skills are more successful in putting the patient at the center of their communication efforts [42].A patient-centered care model encourages and empowers patients to make medical decisions, and a greater patient–doctor concordance may result in higher satisfaction for both parties [1].

In contrast to previous findings, the majority of patients in our study were very realistic about their health situation. Their primary treatment goals were hope for improvement and life prolongation, which was mentioned by relatively few patients. In previous studies in patients with incurable cancer, a third of the patients reported that quality of life was their primary treatment goal, and another third wished for prolongation of life. The remaining third had no preferred treatment goal [43, 44].

It is well known that hopes shift during the successive phases of illness, and patients reconceptualize their goals of treatment. Patients in our study were in the late phase of their disease. After more than one palliative treatment, which was the case for most patients, they had already passed the shock and denial phase regarding their malignancy and the attendant emotional ups and downs. Their goal of “hope for improvement” (feeling better and less symptom burden) reflects the third stage of maturation, which is transformation [45].

Our study has some limitations. The lack of other predictors of SWTD in the multivariate analysis may be due to inherent limitations in the instrument used to assess SWTD. Although we used a validated scale [18], the clustering of scores at the upper end of the scales may indicate a ceiling effect. In such cases, some actual variation in the data is not reflected in the scores obtained from that instrument and this may reduce the statistical power to show associations between that variable and another. However, another study using this measure in a similar population found lower median SWTD scores compared with our findings [5]. On the other hand, a large number of incomplete questionnaires reduced the power of our multivariate analysis. In addition, due to the cross-sectional design, this study captures only a single point during the treatment process, not taking into consideration potential changes in SWTD in subsequent chemotherapy cycles or treatment stages. Because patient-reported assessment of preferred and actual decision-making was assessed at the same point, some bias with respect to the level of agreement may not be excluded. Further, generalization of the study results have to be made with caution as the results might be biased by the positive attitude for communication.

Aiming to achieve the best possible outcome for every patient in the palliative stage of disease does not exclude the approach of goal-oriented patient care. However, more research is needed to understand the consequences of this new approach by integrating the patient’s preferences and goals on more traditional endpoints like survival time and quality of life.

Conclusions

Our study was conducted in the setting of an oncology network and demonstrates that SWTD was generally high and, among other factors, a reasonable consultation time is associated with high patient satisfaction. DMP in this patient group is more likely a doctor-directed or shared-decision model and subjective treatment goals address hope for improvement. Evaluating a patient’s main treatment goals and DMP adds important information that should be considered before discussing a new line of palliative treatment.

References

Korsch BM, Gozzi EK, Francis V (1968) Gaps in doctor–patient communication. 1. Doctor–patient interaction and patient satisfaction. Pediatrics 42:855–871

Zachariae R, Pedersen CG, Jensen AB et al (2003) Association of perceived physician communication style with patient satisfaction, distress, cancer-related self-efficacy, and perceived control over the disease. Br J Cancer 88:658–665

Hall JA, Roter DL, Katz NR (1988) Meta-analysis of correlates of provider behavior in medical encounters. Med Care 26:657–675

Epstein RM, Street R Jr (2007) Patient-centered communication in cancer care: promoting healing and reducing suffering. National Cancer Institute, Bethesda

Leighl NB, Shepherd HL, Butow PN et al (2011) Supporting treatment decision making in advanced cancer: a randomized trial of a decision aid for patients with advanced colorectal cancer considering chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 29:2077–2084

Degner LF, Kristjanson LJ, Bowman D et al (1997) Information needs and decisional preferences in women with breast cancer. JAMA 277:1485–1492

Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, Finkelman MD, Mack JW, Keating NL, Schrag D (2012) Patients’ expectations about effect of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. NEJM 367:1616–1625

Leighl NB, Butow PN, Tattersall MHN (2004) Treatment decision aids in advanced cancer: when the goal is not cure and the answer is not clear. J Clin Oncol 22:1759–1762

O’Connor AM, Rostom A, Fiset V, Tetroe J, Entwistle V, Llewellyn-Thomas H, Holmes-Rovner M, Barry M, Jones J (1999) Decision aids for patients facing health treatment or screening decisions: systemic review. BMJ 319:731–734

Molenaar S, Sprangers MA, Postma- Schmit FC et al (2000) Feasibility and effects of decision aids. Med Decis Making 20:112–127

Committee on Quality of Health Care in America IoM (2001) Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. National Academies Press, Washington, DC

Kuehn BM (2012) Patient-centered care model demands better physician–patient communication. JAMA 307:441–442

Kissane DW, Bylund CL, Banerjee SC, Bialer PA, Levin TT, Maloney EK, D’Agostino TA (2012) Communication skills training for oncology professionals. J Clin Oncol 30:1242–1247

Haidet P, Fecile ML, West HF et al (2009) Reconsidering the team concept: educational implications for patient-centered cancer care. Patient Educ Couns 77:450–455

Politi MC, Studts JL, Hayslip JW (2012) Shared decision making in oncology practice: what do oncologists need to know? Oncologist 17:91–100

Daneault S, Dion D, Sicotte C, Yelle L, Mongeau S, Lussier V, Coulombe M, Paillé P (2010) Hope and noncurative chemotherapies: which affects the other? J Clin Oncol 28:2310–2313

Ware JE Jr, Snyder MK, Wright WR et al (1983) Defining and measuring patient satisfaction with medical care. Eval Program Plann 6:247–263

Holmes-Rovner M, Kroll J, Schmitt N et al (1996) Patient satisfaction with health care decisions: the satisfaction with decision scale. Med Decis Making 16:58–64

Degner LF, Sloan JA, Venkatesh P (1997) The Control Preferences scale. Can J Nurs Res 29:21–43

Lohaus A, Schmitt GM (1989) Control beliefs concerning illness and health: report on the development of a testing procedure. Diagnostica 35:59–72

Wallston KA, Wallston BS, DeVellis R (1978) Development of the Multidimensional Health Locus of Control (MHLC) scales. Health Educ Monogr 6:160–170

Butow P, Coates A, Dunn S, Bernhard J, Hurny C (1991) On the receiving end. IV: validation of quality of life indicators. Ann Oncol 2:597–603

Bernhard J, Maibach R, Thurlimann B et al (2002) Patients’ estimation of overall treatment burden: why not ask the obvious? J Clin Oncol 20:65–72

Hürny C, Wegberg B, Bacchi M, Bernhard J, Thürlimann B, Real O, Perey L, Bonnefoi H, Coates A (1998) Subjective health estimations (SHE) in patients with advanced breast cancer: an adapted utility concept for clinical trials. Br J Cancer 77:985–991

Bernhard J, Dietrich D, Scheithauer W et al (2008) Clinical benefit and quality of life in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer receiving gemcitabine plus capecitabine versus gemcitabine alone: a randomized multicenter phase III clinical trial—SAKK 44/00-CECOG/PAN.1.3.001. J Clin Oncol 26:3695–3701

Kollbrunner J, Zbaren P, Quack K (2001) Quality of life stress in patients with large tumors of the mouth. 2: Dealing with the illness: coping, anxiety and depressive symptoms. HNO 49:998–1007

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd edn. Taylor & Francis, New York

Cronbach LJ (1951) Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 16:297–334

Van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K (2011) Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw 45:1–67

Cohen J (1960) A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas 20:37–46

Deveugele M, Derese A, van den Brink-Muinen A et al (2002) Consultation length in general practice: cross sectional study in six European countries. BMJ 325:472

Hamidou Z, Dabakuyo TS, Bonnetain F (2011) Impact of response shift on longitudinal quality-of-life assessment in cancer clinical trials. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 11:549–559

Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A (2000) The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract 49:796–804

Makoul G, Arntson P, Schofield T (1995) Health promotion in primary care: physician–patient communication and decision making about prescription medications. Soc Sci Med 41:1241–1254

Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S (2012) Shared decision making—pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med 366:780–781

Bruera E, Sweeney C, Calder K, Palmer L, Benisch-Tolley S (2001) Patient preferences versus physician perceptions of treatment decisions in cancer care. J Clin Oncol 19:2883–2885

Elkin EB, Kim SH, Casper ES, Kissane DW, Schrag D (2007) Desire for information and involvement in treatment decisions: elderly cancer patients’ preferences and their physicians’ perceptions. J Clin Oncol 25:5275–5280

Bruera E, Willey JS, Palmer JL, Rosales M (2002) Treatment decisions for breast carcinoma: patient preferences and physician perceptions. Cancer 94:2076–2080

Mandelblatt J, Kreling B, Figeuriedo M, Feng S (2006) What is the impact of shared decision making on treatment and outcomes for older women with breast cancer? J Clin Oncol 24:4908–4913

Janz NK, Wren PA, Copeland LA, Lowery JC, Goldfarb SL, Wilkins EG (2004) Patient–physician concordance: preferences, perceptions, and factors influencing the breast cancer surgical decision. J Clin Oncol 22:3091–3098

Gattellari M, Butow PN, Tattersall MH (2001) Sharing decisions in cancer care. Soc Sci Med 52:1865–1878

Noble LM, Kubacki A, Martin J, Lloyd M (2007) The effect of professional skills training on patient-centredness and confidence in communicating with patients. Med Educ 41:432–440

Voogt E, van der Heide A, Rietjens JA et al (2005) Attitudes of patients with incurable cancer toward medical treatment in the last phase of life. J Clin Oncol 23:2012–2019

Stiggelbout AM, de Haes JC, Kiebert GM et al (1996) Tradeoffs between quality and quantity of life: development of the QQ Questionnaire for Cancer Patient Attitudes. Med Decis Making 16:184–192

Renz M, Koeberle D, Cerny T, Strasser F (2008) Between utter despair and essential hope. J Clin Oncol 27:146–149

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Margit Hemetsberger (Hemetsberger Medical Services, Vienna, Austria), Eva Müller (Lifescience Texte, Vienna, Austria), and Julia Balfour (Northstar Medical Writing and Editing Services, Dundee, UK), who assisted with the preparation of this manuscript and were funded by the Kantonsspital St. Gallen, Switzerland. The authors also thank Ivo Betschard for data preparation, and all patients, oncologists, and nurses at each participating center.

Funding

This study was supported by OSKK (Ostschweizer Stiftung für Klinische Krebsforschung).

Conflict of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 108 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hitz, F., Ribi, K., Li, Q. et al. Predictors of satisfaction with treatment decision, decision-making preferences, and main treatment goals in patients with advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer 21, 3085–3093 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-013-1886-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-013-1886-4