Abstract

Purpose

This study aims to describe the supportive care needs of informal caregivers (ICG) of adult bone marrow transplant (BMT) patients. In addition, we explored relationships between levels of unmet need, psychological morbidity and patient and ICG characteristics.

Methods and sample

We invited patients within 24 months of BMT to participate in a cross-sectional survey. Consenting patients asked their ICG to complete and return the questionnaire booklet. Measures included the Supportive Care Needs Survey Partners and Carers and General Health Questionnaire.

Key results

Two hundred patients were approached, and 98 completed questionnaires were received (response rate = 49 %). We found high unmet need and psychological morbidity among ICGs and an association between ICG unmet need and psychological morbidity. Patient functioning, particularly anxiety and depression, sexual dysfunction and resumption of usual activities impacted on ICG unmet need and psychological morbidity. No associations were found between ICG unmet need and psychological morbidity and the following variables: type of BMT, time from BMT, ICG gender, number of dependents and patient age.

Conclusion

ICG of BMT patients have high levels of unmet need and psychological morbidity in the months that follow a BMT. This highlights the importance of thorough needs assessment to ensure limited resources are targeted to those most in need.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Caring for a person with cancer can have a significant impact on friends and family [1, 2]. Patients undergoing bone marrow transplant (BMT) have a uniquely demanding, often extremely toxic treatment trajectory [3] and thus can lean heavily on friends and family for support [4]. Yet no UK study to date has explored the needs of informal caregivers (ICG) of BMT patients. This study aimed to describe the needs of ICG of BMT patients and explore relationships between ICG unmet need, psychological morbidity and biographical characteristics.

Literature review

Caring is a complex and much defined concept [5]. Caring broadly encompasses practical and affective activities of ‘caring for’ and ‘caring about’ a person [6]. The act of caring is often divided into two distinct groups, namely care provided by formal caregivers, such as health care professionals working within professional networks, and care provided by family and friends [7]. UK policy documents have adopted the term ICG to convey unwaged caring provided out of love for friends and family [1]. This study will utilise this term.

ICGs of cancer patients typically provide physical and emotional care [8], have financial and social concerns [9, 10] and support their families, in addition to managing their own lives [11]. There is increasing interest in the cancer literature regarding the effects of caring on the health of ICGs [11–13]. Studies have highlighted ICGs are likely to suffer from anxiety and depression [11, 13], sleep deprivation and fatigue [12], sexual problems [14], greater vulnerability to physical illness [5], and feel frustration, resentment and fear [15]. Some authors suggest ICGs find the cancer experience to be as distressing and stressful as patients [16, 17], and this is made worse if patients continue to be symptomatic and unable to perform activities of daily living once treatment is completed [18, 19]. These findings are mirrored in the limited number of papers investigating needs of ICGs of BMT patients whereby ICGs report suffering from fatigue, depression and had problems with sleeping and sexual function [20, 21].

Certain factors such as gender, age, income, patient status, ICG health, dependents and educational status are associated with increased ICG distress [7, 11, 13, 17, 19–25]. Furthermore, ICGs with limited social support networks and additional caring responsibilities consistently report more distress [7, 18]

As ICG are at risk of psychological distress, their unmet needs must be assessed to enable services to try to address their needs and thereby reduce the risk of psychological morbidity. Needs assessment enables researchers and clinical teams to assess the gap between services people perceive they need and the services they receive [26]. This enables services to direct funds to areas where patients and ICGs feel they have the most need, thus maximising the effects of intervention and funding. Thus, needs assessment is becoming an increasingly popular approach [27].

There is a growing body of knowledge regarding the needs of ICGs of non-BMT cancer patients [8, 17, 28, 29]. Hodgkinson et al. [19] conducted a cross-sectional survey in Australia using the Cancer Survivors’ Partners Unmet Needs (CaSPUN) instrument with 154 ICGs of gynaecological, breast, prostate and colorectal disease-free cancer patients. Over 50 % reported at least one unmet need (mean = 2.3 unmet needs) and relationships were found between unmet need and psychological distress. Thomas et al. [7] conducted a 3-year study with 262 ICGs of lung, breast, lymphoma and colorectal cancer patients. Each ICG completed a questionnaire and 32 were interviewed. This sample generated a number of papers which each took a different angle: care given by ICGs [7], unmet psychosocial needs of ICGs [18], ICGs place within the medical setting [30], and universal, situational and personal needs of ICGs [23]. Hodgkinson et al. [19] found 53 % of ICG reported unmet need and similarly, Soothill et al. [18] found 43 % of ICGs reported at least one unmet need. Only a seventh of the sample reported multiple unmet needs (equal to or greater than ten).

Limited research has been carried out exploring the needs of ICGs of BMT patients specifically. No UK-based study has been identified. Most BMT and ICG studies are from America and do not focus on ICG unmet need but effects of BMT on relationships [31–34] or health of ICG [4, 20, 21, 35]. In relation to health studies, it has been found that ICG suffered from fatigue, depression, insomnia and sexual dysfunction [4, 20, 21]. Fife et al. [4] found that symptoms experienced by the recipient had a greater impact in ICGs compared to type of BMT (autologous or allogeneic). Similarly, Bishop et al. [21] found that the type of BMT made no difference on spousal psychological outcomes. In contrast, Langer et al. [31] found marital satisfaction decreases over 1 year for partners of allogeneic BMT recipients.

In summary, ICGs play an important role in supporting patients through their cancer journey [7] and BMT [31–33], yet the act of caring appears to have a negative impact on the physical and psychological health of ICGs of cancer patients [4, 21] and results in unmet needs for support [7, 19]. Although BMT is one of most challenging cancer treatments available [3], no UK-based study has been identified exploring supportive care needs of ICGs of BMT patients. This study, therefore, aimed to describe the supportive care needs of ICGs of adult BMT patients. We also aimed to explore relationships between levels of unmet need, psychological morbidity and patient and ICG characteristics. Specific objectives were as follows:

-

1

to identify supportive care needs of ICGs of adult BMT patients

-

2

to establish prevalence of psychological morbidity among ICGs

-

3

to explore relationships between unmet need and ICG psychological morbidity

-

4

to identify patient and ICG characteristics associated with high levels of unmet need

-

5

to identify patient and ICG characteristics associated with ICG psychological morbidity.

Method

A quantitative, cross-sectional, survey research design was adopted. Data were collected using a self-administered postal questionnaire booklet which comprised the Supportive Care Needs Survey Partners & Carers (SCNS-P&C), General Health Questionnaire (GHQ12) and a section on biographical characteristics.

The SCNS-P&C is a 44-item newly developed instrument to assess need for help for partners and caregivers of cancer patients [36]. This has been adapted from the Supportive Care Needs Survey (SCNS) [27]. The SCNS assesses patients’ need for help and has demonstrated good validity and reliability [27]. The structure and format of SCNS-P&C was modelled on SCNS and respondents indicate on a five-point response scale their level of need for help for each item in the preceding month [27, 36]. A respondent is deemed to have no need for an item if they score one or two; some unmet need if their response is a three, four or five; and moderate to high need if they respond with a four or five [36]. The SCNS-P&C was under development during this study; thus the domain structure had not been finalised. However, psychometric testing demonstrated face and content validity and acceptable reliability (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient = 0.88–0.94) [36].

The GHQ12 is a commonly used 12-item scale to measure emotional upset or distress in community settings [37]. Patients rate their general health over the last few weeks [38]. Scores are summed and used to assess whether an individual can be classified as ‘a case’ or ‘not a case’. Goldberg et al. [38] recommend using mean GHQ score of each sample to indicate a case. Thus, in our study, the mean GHQ12 score was calculated for the sample and used as the threshold for deciding caseness.

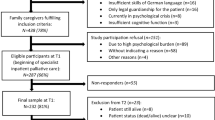

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for study are outlined in Box 1. Participant pathway through the study is demonstrated in Fig. 1. Potential participants were sent an invitation letter to participate in the study and a questionnaire pack. Consenting patients passed the questionnaire pack to their ICG who completed and returned the questionnaire. National Research Ethics Committee and local Research and Development Committee approval was obtained for the study (REC reference number 09/H0721/26).

Box 1

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Data analysis

Unmet needs were identified by descriptive analysis. Prevalence of some, moderate and high unmet need was calculated. We were interested in identifying areas where ICGs have the highest level of unmet need; therefore, for subsequent analyses, unmet needs included moderate and high unmet need only. Prevalence of multiple unmet needs was calculated by summing the number of items participants reported moderate and high unmet need for. The mean number of unmet needs per participant was calculated and used as cutoff to categorise the level of unmet need into none, few and multiple.

Total scores GHQ12 were calculated, and univariate analysis was conducted to demonstrate the prevalence of cases of psychological morbidity. Bivariate analysis was conducted to explore relationships between ICG unmet need, ICG psychological morbidity and biographical characteristics. Cross tabulation was used to highlight patterns between level of moderate and high unmet need and (1) psychological morbidity, (2) patient characteristics and (3) ICG characteristics. Non-parametric statistical tests were applied to test for presence and strength of associations between variables. ICG psychological morbidity and patient and ICG characteristics were similarly cross-tabulated. Chi-square tests, Spearman’s rank order coefficient tests and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used as appropriate to demonstrate associations.

Findings

Sample

Two hundred patients were asked to give their ICG a questionnaire booklet. One hundred thirty-nine (70 %) ICG and/or patients responded and 49 % of ICGs (n = 98) completed and returned the questionnaires. Thirteen percent (n = 25) of patients opted out and 8 % (n = 16) of ICGs opted out. Participating patients were representative of the total population with respect to age, gender, diagnosis and type of BMT. Table 1 gives the characteristics of ICG who participated. ICGs were slightly older than patients and mostly white British, married to patient, homeowners and had formal qualifications. Almost 40 % had a long-standing illness. Four-fifths thought patients had at least one symptom but believed they had resumed usual activities at least in part.

Overall questionnaire findings

Table 2 outlines the percentage of participants with at least one moderate or high unmet need and the mean (SD) number of moderate or high unmet needs for whole sample. Two thirds of ICG had at least one moderate or high unmet need and almost half had psychological morbidity. Scores were not normally distributed; thus, non-parametric statistical tests were performed.

Descriptive analysis of unmet need

Analysis occcurred in two phases. Firstly, unmet need for individual items was assessed, and secondly, levels of unmet need per participant were calculated. The ten most frequently endorsed unmet needs are shown in Table 3. In order to assess total levels of unmet need for individual participants, a total need score was calculated for each participant. Respondents reported a mean of seven unmet needs and this was used as a cutoff point, and total scores were grouped into no needs (zero), few needs (one to seven) and multiple needs (equal to or greater than eight). Roughly, a third reported no unmet needs (n = 34, 35 %), a third had few unmet needs (n = 33, 34 %) and a third had multiple unmet needs (n = 31, 32 %).

Prevalence of psychological morbidity among ICGs

In this sample, the mean GHQ score was 3.10 (SD 3.44). Using 3 as the threshold for caseness, almost half (n = 45) of ICGs were classified as cases of psychological morbidity.

Unmet need and psychological morbidity

Cross tabulation between the total number of unmet needs categorised into none, few and multiple and GHQ case vs. non-case highlighted that the greater the number of unmet needs ICGs reported, the more likely they were to be a GHQ case (Table 4). Over three quarters of cases had multiple needs (χ2 (2, n = 98) = 23.333, p = 0.000, Cramer’s V 0.488). Inspection of mean ranks for each category suggests that those with multiple needs had higher GHQ12 scores and those with no unmet needs had lower GHQ12 scores (no needs, mean rank 29.56; few needs, mean rank 52.59; multiple needs, mean rank 68.08). The difference was statically significant (no needs, n = 34; few needs, n = 33; multiple needs, n = 31; χ2 (2, n = 98) = 31.92, p = 0.000).

Biographical characteristics and unmet need

Associations were sought between (1) biographical characteristics of patients and number of ICG unmet needs and (2) biographical characteristics of ICGs and ICG unmet need. ICG total unmet moderate or high need was categorised as none, few (one to seven) or multiple (equal to or greater than eight). Statistically significant results are shown in Table 5. Associations were found between number of ICG unmet needs and whether ICG considered the patient to have resumed their usual activities (χ2 (4, n = 98) = 11.92, p = 0.018, Cramer’s V = 0.018; rho = 0.282, n = 98, p = 0.005), if ICG perceived their relative (patient) to have anxiety and depression (χ2 (2, n = 98) = 6.118, p = 0.047, Cramer’s V = 0.04; rho = −0.216, n = 98, p = 0.032) and finally ICG perceived their relative (patient) to have sexual dysfunction (χ2 (2, n = 98) = 11.044, p = 0.004, Cramer’s V = 0.004; rho = −0.330, n = 98, p = 0.01). There was a trend for an association between the number of unmet needs ICGs reported and patient gender (χ2 (2, n = 98) = 5.075, p = 0.079) and patient fatigue (χ2 (2, n = 98) = 5.278, p = 0.071). Associations were tested but were not found between the number of ICG unmet needs and type of BMT, time since BMT, patient suffering gut problems or infections. Similarly, ICG unmet needs and ICG characteristics were cross-tabulated and no associations were found between the following: ICG gender, ICG age, marital status, employment status, educational level, accommodation, number of ICG dependents, relationship to patient and if they had long-standing illness or disability.

Biographical characteristics and ICG psychological morbidity

Cross tabulation was conducted on both patient and ICG biographical characteristics and ICG GHQ ‘caseness’. Two patient characteristics were found to be associated with ICG GHQ caseness. Firstly, ICG perceived patient anxiety and/or depression (with Yates continuity correction) (χ2 (1, n = 98) = 7.60, p = 0.011, phi = −0.278; rho = 0.278, n = 98, p = 0.006) (Table 6) and secondly, ICG perceived patient sexual dysfunction (with Yates continuity correction) (χ2 (1, n = 98) = 10.27, p = 0.003, phi = −0.324; rho = 0.324, n = 98, p = 0.001) (Table 6). Cross tabulation highlighted an association between ICG age and psychological morbidity (χ2 (2, n = 98) = 9.4, p = 0.009, Cramer’s V 0.31). However, when investigated further, the association was not significant (Spearman’s rho = 0.117, n = 98, p = 0.251).

Cross tabulation demonstrated no associations between ICG GHQ caseness and patient gender, age, diagnosis, resumption of usual activities, type of BMT, time since BMT, ICG perceived patient fatigue, infections, gut problems, breathing difficulties, graft versus host disease or other symptoms. Similarly, no associations were found between ICG GHQ caseness and ICG gender, ethnicity, marital status, employment status, education level and accommodation, number of dependents, relationship to patient and suffering from long-standing illness or disability.

Discussion

ICGS reported high levels of unmet need and almost half had psychological morbidity. This suggests caring had a significant impact on ICGs psychological wellbeing. Two thirds of ICG had at least one moderate or high unmet supportive care need, which is higher than that reported by Hodgkinson et al. [19] (53 %) and Soothill et al. [18] (43 %). This finding is supported by a higher mean number of moderate and high unmet needs per ICG identified in our study than was reported by Hodgkinson et al. [19] (6.5 vs 2.3, respectively). Finally, over a third of our sample had multiple unmet needs (equal to or greater than seven). This contrasts to that of Soothill et al. [18] who found that only a seventh of their sample had multiple unmet needs (equal to or greater than ten); however, variations may be attributed to differing cutoff points defining multiple unmet needs. Also, each study had different patient and ICG populations. Previous studies did not focus on ICGs of BMT patients. BMT is highly toxic, has more side effects and involves long-term immunosuppression; thus, patients and ICG may be traumatised by the experience which may be reflected in subsequent levels of unmet need [3]. Furthermore, the study samples did not have comparable ratios of females to males. Our sample consisted of more female participants than others [19], and previous studies have shown that female ICG report greater distress than male ICG [7, 13]. Comparisons are also difficult to make because different research instruments were used. Hodgkinson et al. [19] utilised a tool that focuses on disease-free cancer survivors (CaSPUN), whereas SCNS-P&C specialises in the needs of those undergoing treatment [36]. Thus, dimensions of tools differ and SCNS-P&C may have picked up more unmet need. Both tools are at risk of recall bias as they ask for ICG’s level of need in the last month; thus, ICGs may not remember accurately. Further differences could be attributed to definitions of unmet need. This study only included moderate and high unmet need. However, Hodgkinson et al. [19] classified weak, moderate and strong unmet need as unmet need. Therefore, it could be expected that Hodgkinson et al. [19] would identify more unmet needs; however, the opposite occurred. This could be because their sample was disease-free and had years post-treatment. Finally, the research setting may have contributed to differing levels of unmet need reported. Our study recruited from a tertiary treatment centre, and so patients and ICG may not have been linked with local services and thus were unable to draw support from them. Finally, differences may reflect differing healthcare systems, as in a study by Hodgkinson et al. [19] conducted in Australia.

Almost half of ICGs were defined as being cases of psychological morbidity; this represents more than twice the expected percentage of psychological distress for UK populations [39]. Studies looking at ICGs of non-BMT cancer patients [11, 13, 18] and BMT patients [21] have found equally high levels of psychological morbidity.

We found an association between high ICG unmet need and ICG psychological morbidity. This supports findings from studies of non-BMT cancer patients; Soothill et al. [18] found that 71 % of ICGs with unmet need had high GHQ12 scores, and Hodgkinson et al. [19] found a positive relationship between unmet carer need and ICG psychological morbidity. Again, this implies that the act of caregiving is related to high unmet need and psychological morbidity rather than specific patient treatments. ICG distress may not relate to the toxicity of treatment.

This study found some interesting associations between sample characteristics, ICG need and psychological morbidity. ICGs who perceived their relative to be anxious or depressed had higher levels of unmet need and more psychological morbidity themselves. This mirrors findings from mental health studies whereby ICGs of depressed patients have multiple needs [40]. Furthermore, anxiety and depression may lead to sexual dysfunction [41], and this study found ICG perceived patient sexual dysfunction was associated with ICG unmet need and psychological morbidity. Soothill et al. [18] found that 50 % of carers had unmet sexual needs, and Hodgkinson et al. [19] found that both ICG and patients had unmet need addressing problems in their sex life. However, ours is the first study to explore the relationship between ICG perceived patient sexual dysfunction and the number of unmet ICG needs. Anxiety and depression may also lead to reduced patient activity [3] which may affect ICGs. Fewer ICG reported multiple unmet needs if patients had resumed usual activities. This reflects other studies findings. Soothill et al. [18] found relationships between ICG unmet need patient functioning with activities of daily living, and Hodgkinson et al. [19] found associations between patient survivorship phase and ICG unmet need.

There is evidence female ICGs of cancer patients report more distress than males [7, 13, 21]. However, no gender associations were found. This may reflect a ‘true’ finding or reflect limited heterogeneity in the sample as less than a third were male. Studies where associations were found had roughly equal numbers of men and women ICGs [7, 13, 21]

ICG psychological health has been shown to be associated with level of ICG unmet need [19, 21]. However, we found no association with unmet need or psychological morbidity despite over a third of ICGs report long-standing illnesses or disability. Similarly, Soothill et al. [18] found no association despite a third of the sample are suffering from illness or disability.

In this study, ICG of younger patients (≤40 years) reported high number of unmet needs. This is mirrored by findings from studies by Hodgkinson et al. [19], who found that patient age was related to the number of ICG unmet needs, and by Armes et al. [42], who found that younger age predicted unmet need in patients. We did not find, however, that ICG age was associated with increased unmet needs or psychological morbidity.

Soothill et al. [18] found that ICGs with other caring responsibilities had increased unmet need. No association was found in this study despite that 40 % of ICG have dependents, as compared to 20 % in the study by Soothill et al. [18]. In addition, we found no association between ICGs educational level and psychological morbidity. This reflects finding from other studies such as those of Papastavrou et al. [13] who found that ICGs with lower educational levels reported more depression.

In keeping with Bishop et al. [21] and Fife et al. [4], no statistical difference was found between the number of unmet ICG needs or psychological morbidity and type of BMT. This was surprising as it is generally regarded that allogeneic BMT is a tougher, more demanding regimen for recipients [3]. It may be that the sample size of the two groups within studies may not be large enough to highlight any differences. Furthermore, autologous BMT is more common, and so samples may contain greater numbers of autologous patients. This was true for the current sample whereby three quarters were autologous BMT patients. It could also be attributed to patients and ICGs only having experience of their particular treatment.

Limitations

This study had a number of limitations. A cross-sectional design only provides a snapshot of a situation at a given time, whilst a longitudinal study would have enabled causal analysis and changes in ICG need over time to be captured. Nevertheless, it does provide an insight into ICG needs and psychological morbidity. Although the sample size was relatively small, it was representative of the population, and the study achieved a good response rate (70 % to initial invitation to participate, 49 % completed and returned questionnaires). Bowling [43] considers 70 % a meaningful response rate. Therefore, we can be reasonably confident that the results reflect the population.

Ten percent (n = 10) of ICGs telephoned to explain their level of unmet need had been differently closer to BMT. Thus, it may have been better to subdivide patients into those who were less than a year from their BMT and those who were greater than 1 year.

Practice implications

This study found that ICGs experience multiple unmet needs and report high levels of psychological morbidity. Yet services have limited resources to assess ICG’s needs, and few are currently set up to meet ICG need. This highlights the importance of thorough needs assessment of ICGs at initial contact to ensure resources are targeted to those most in need. ICGs should be informed that support is available to them and contact details of clinical staff provided. Assurances should be given that complementary therapies and counselling services are available to support ICGs as well as patients. Furthermore, ICGs can be directed to internal therapy services where available and external sources of support such as charity and government support groups. Clinical staff need be aware of potential financial consequences of caring and guide ICG to welfare support teams when suitable. Finally, clinical teams need to be proactive with carers who do not always voice their concerns.

Recommendations for future research

The following are suggested for future research:

-

prospective longitudinal study to see if needs change over time and identify predictors of unmet need;

-

qualitative research, using interviews or focus groups, to explore ICG needs around what kind of support would be helpful;

-

study to explore the relationship between the unmet needs of patients and those of ICGs; and

-

further psychometric evaluation of needs assessment tools.

Conclusion

This study has identified that ICG of BMT patients have high levels of unmet need and psychological morbidity. This highlights the importance of thorough needs assessment of ICG of BMT patients to ensure limited resources are targeted to those most in need. Future research is required to investigate how needs change over time and identify predictors of unmet needs.

References

Department of Health (2000) The NHS plan. London

Department of Health (2007) The cancer reform strategy. London.

Mosher C, Redd W, Rini CM, Burkhalter JE, DuHamel KN (2009a) Physical, psychological, and social sequelae following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a review of the literature. Psycho-Oncology 18(2):113–127

Fife BL, Monahan PO, Abonour R, Wood LL, Stump TE (2008) Adaptation of family caregivers during the acute phase of adult BMT. Bone Marrow Transplantation 42:1–8

Krishnasamy M, Plant H (2004) Carers, caring and cancer related fatigue. In: Armes J, Krishnasamy M, Higginson I (eds) Fatigue in cancer. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Cribb A (2001) Knowledge and caring: A philosophical and personal perspective. In: Corner J, Bailey C (eds) Cancer nursing: Care in context. Blackwell Science, Oxford

Thomas C, Morris SM, Harman JC (2002) Companions through cancer: the care given by informal carers in cancer contexts. Soc Sci Med 54(4):529–544

Bee PE, Barnes P, Luker KA (2008) A systematic review of informal caregivers’ needs in providing home-based end-of-life care to people with cancer. J Clin Nurs 1–15

Laizner AM, Shegda Yost LM, Barg F, McCorkle R (1993) Needs of family caregivers of persons with cancer: a review. Semin Oncol Nurs 9(2):114–120

Wilson K, Avir Z (2008) Cancer and disability benefits: a synthesis of qualitative findings on advice and support. Psycho-Oncology 17:421–429

Ussher JM, Sandoval M (2008) Gender differences in the construction and experience of cancer care: the consequences of the gendered positioning of carers. Psychol Heal 23(8):945–963

Carter PA (2003) Family caregivers’ sleep loss and depression over time. Cancer Nurs 26(4):253–259

Papastavrou E, Charalambous A, Tsangari H (2009) Exploring the other side of cancer care: the informal caregiver. Eur J Oncol Nurs 13:128–136

Gilbert E, Ussher JM, Perz J (2008) Renegotiating sexuality and intimacy in the context of cancer: the experiences of carers. Arch Sex Behav 39(4):998–1009

Grbich C, Maddocks I, Parker D (2001) Family caregivers, their needs and home-based palliative cancer services. J Fam Stud 7:171–188

Bowman K, Rose J, Deimling GT (2006) Appraisal of the cancer experience by family members and survivors in long term survivorship. Psycho-Oncology 15:834–845

Hagedoorn M, Sanderman R, Bolks HN, Tuinstra J (2008) Distress in couples coping with cancer: a meta-analysis and critical review of role and gender effects. Psychol Bull 134(1):1–30

Soothill K, Morris SM, Harman JC, Francis B, Thomas C, McIllmurray MB (2001) Informal carers of cancer patients: what are their unmet psychosocial needs? Health Soc Care Community 9(6):464–475

Hodgkinson K, Butow P, Hunt GE, Pendlebury S, Hobbs KM, Lo SK, Wain G (2007) The development and evaluation of a measure to assess cancer survivors’ unmet supportive care needs: the CaSUN (Cancer Survivors’ Unmet Needs measure). Psycho-Oncology 16(9):796–804

Gaston-Johansson F, Lachica EM, Fall-Dickson JM, Kennedy MJ (2004) Psychological distress, fatigue, burden of care, and quality of life in primary caregivers of patients with breast cancer undergoing autologous bone marrow transplantation. Oncol Nurs Forum 31(6):1161–1169

Bishop MM, Beaumont JL, Hahn EA, Cella D, Andrykowski MA, Brady MJ, Horowitz MM, Sobocinski KA, Rizzo JD, Wingard JR (2007) Late effects of cancer and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation on spouses or partners compared with survivors and survivor matched controls. J Clin Oncol 25(11):1403–1411

Eriksson E, Lauri S (2000) Informational and emotional support for cancer patients’ relatives. Eur J Cancer Care 9:8–15

Soothill K, Morris SM, Thomas C, Harman JC, Francis B, McIllmurra MB (2003) The universal, situational, and personal needs of cancer patients and their main carers. Eur J Oncol Nurs 7(1):5–13

Yun YH, Rhee YS, Kang IO, Lee JS, Bang SM, Lee WS, Kim JS, Kim YS, Shin SW, Hong YS (2005) Economic burdens and quality of life of family caregivers of cancer patients. Oncology 68(2):107–144

Dumont J, Allard P, Gagnon P, Charbonneau C, Vézina L (2006) Caring for a loved one with advanced cancer: determinants of psychological distress in family caregivers. J Palliat Med 9(4):912–921

Carr W, Wolfe S (1976) Unmet needs as sociomedical indictors. Int J Heal Serv 6:417–430

Bonevski B, Sanson-Fisher RW, Girgis A, Burton L, Cook P, Boyes A, Supportive Care Review Grou et al (2000) Evaluation of an instrument to assess the needs of patients with cancer. Cancer 88(1):217–225

Harding R, Higginson IJ (2003) What is the best way to help caregivers in cancer and palliative care? A systematic literature review of interventions and their effectiveness. Palliat Med 17(1):63–74

Plant H, Sherwin A, Moore S, Medina J, Ream E, Richardson A (2006) Developing and evaluating a supportive nursing intervention for family members of people with lung cancer. Kings College London

Morris S, Thomas C, Soohill K (2001) The carer’s place in the cancer situation: where does the carer stand in the medical setting? Eur J Cancer Care 10(2):87–95

Langer S, Abrams J, Syrjala K (2003) Caregiver and patient marital satisfaction and affect following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a prospective, longitudinal investigation. Psychooncology 12(3):239–253

Langer SL, Yi JC, Storer BE, Syrjala KL (2009) Marital adjustment, satisfaction and dissolution among hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients and spouses: a prospective, five-year longitudinal investigation. Psycho-Oncology 12:239–253, 2003

Eldredge DH, Nail LM, Maziarz RT, Hansen LK, Ewing D, Archbold PG (2006) Explaining family caregiver role strain following autologous blood and marrow transplantation. 24(3):53–74

Williams L (2007) Whatever it takes: informal caregiving dynamics in blood and marrow transplantation. Oncol Nurs Forum 34(2):379–387

Keogh F, O’Riordan J, McNamara C, Duggan C, McCann SR (1998) Psychosocial adaptation of patients and families following bone marrow transplantation: a prospective, longitudinal study. Bone Marrow Transplant 22(9):905–911

Girgis S, Lambert S, Lecathelinais C (2011) The Supportive care needs survey for partners and carers of cancer survivors: development and psychometric evaluation. Psycho-Oncology 20(4):387–393

King M, Jones L, Nazareth I (2006) Concern and continuity in the care of cancer patients and their carers: a multimethod approach to enlightened management. SDO/13E/2001 London

Goldberg D, Williams P (1988) A user’s guide to the general health questionnaire. nferNelson Publishing Company Ltd, London

Murphy H, Lloyd K (2007) Civil conflict in Northern Ireland and the prevalence of psychiatric disturbance across the United Kingdom: a population study using the British household panel survey and the Northern Ireland household panel survey. Int J Soc Psychiatr 53(5):397–407

Graap H, Bleich S, Herbst F, Scherzinger C, Trostmann Y, Wancata J, de Zwaan M (2008) The needs of carers: a comparison between eating disorders and schizophrenia. Soc Psychiatr Psychiatr Epidemiol 43(10):800–807

Scott Baker K, Rajotte EJ (2012) Late effects after treatment of leukaemia. In Estey. E (ed) Leukaemia and related diseases Humana

Armes J, Crowe M, Colbourne L, Morgan H, Murrells T, Oakley C, Palmer N, Ream E, Young A, Richardson A (2009) Patients’ supportive care needs beyond the end of cancer treatment: a prospective, longitudinal survey. J Clin Oncol. Early Release [accessed online 02.12.09] http://jco.ascopubs.org/cgi/content/abstract/JCO.2009.22.5151v1

Bowling A (2002) Research methods in health, 2nd edn. Open University Press, Berkshire

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Professor Girgis and her team, especially Dr Sylvie Lambert, for allowing the use of the SCNS-P&C whilst it was still in development and Dr Peter Milligan for statistical advice.

Conflict of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Armoogum, J., Richardson, A. & Armes, J. A survey of the supportive care needs of informal caregivers of adult bone marrow transplant patients. Support Care Cancer 21, 977–986 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-012-1615-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-012-1615-4