Abstract

Purpose

The goal of this study was to assess the rehabilitation needs of young women breast cancer survivors under the age of 50 and to identify factors that may impact or prevent cancer rehabilitation utilization.

Methods

Utilizing a grounded theory methodology, 35 young breast cancer survivors were interviewed twice in four Atlantic Canadian provinces.

Results

A considerable number of barriers exist to receiving rehabilitative care post-treatment for young breast cancer survivors. The systemic barriers include the lack of availability of services, travel issues, cost of services, and the lack of support to address the unique needs for this age group. However, the most complicated barriers to accessing rehabilitative care were personal barriers which related more to choice and circumstances, such as the lack of time due to family responsibilities and appointment fatigue. Many of these personal barriers were rooted in the complex set of gender roles of young women as patients, mothers, workers, and caregivers.

Conclusions

The contexts of young women’s lives can have a substantial impact on their decisions to seek and receive rehabilitative care after breast cancer treatment. The systemic barriers can be reduced by introducing more services or financial assistance; however, the personal barriers to rehabilitation services are difficult to ameliorate due to the complex set of roles within and outside the family for this group of young breast cancer survivors. Health care providers need to take into consideration the multiple contexts of women’s lives when developing and promoting breast cancer rehabilitation services and programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common type of cancer and the most common cause of death among young women. It is estimated that 19% percent of all new diagnoses of breast cancer are among women under the age of 50 [6]. Survival has been improving gradually in the past decade, and the 5-year relative survival rate for breast cancer in Canada (excluding Quebec) is now 79% for women under age 40 and 87% for women aged 40–49 [7]. While most cancer treatment options available today are beneficial and lifesaving, they are also associated with many physical, psychological, and social sequelae and thus may have an impact on the quality of life of women surviving breast cancer. Interest in the experience of cancer survivorship and the rehabilitation needs of young women with breast cancer is heightened by the growing number of studies showing that younger women have a greater physical, psychological, and social morbidity and poorer quality of life after a breast cancer diagnosis than older women [2, 3, 13, 21–23, 30, 32]. Age can play a major role in life orientation and in the adaptation to immediate- and long-term stressors such as the effects of cancer; however, not much is really known about the rehabilitation needs and utilization after breast cancer for younger populations [19].

Background

Impact of breast cancer on young women

Breast cancer occurring in young women tends to be more biologically aggressive with higher rates of recurrence [32, 39]. Delays in diagnosis for women occur, particularly under the age of 35, partially due to the lack of breast screening policies for young women [4]. As a result, many young breast cancer patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage, making them more likely to require aggressive treatments and receive adjuvant treatment such as chemotherapy and hormonal therapy. Patients who receive more doses of chemotherapy report a slower improvement in quality of life after initial diagnosis and surgery than those who receive less aggressive treatments [17, 38]. According to Kroenke and colleagues, the differences in responses to breast cancer treatment between young and older women may also be attributed to the higher levels of work, home, and child care responsibilities of younger women which require greater physical effort [22]. Major treatment-related stressors such as physical or psychosocial impairment can place an additional strain upon the patients’ coping abilities and resources when they already have to deal with the impact of a cancer diagnosis. For example, surgery, lymph node dissection, chemotherapy, and radiation can have a long-term, negative effect on arm function and can cause pain, lymphedema, limited range of motion, and fatigue [5, 35]. The potential psychological late effects include fear and anxiety about the cancer coming back, depression, feelings of uncertainty, and isolation. Social effects may include changes in interpersonal relationships, concerns regarding finances and health insurance, and difficulty in returning to work or seeking employment due to impairment. Research shows that younger women with breast cancer also have the highest rate of unmet needs in terms of information and support compared to older women with breast cancer [2, 21, 38].

In addition to the physical and psychosocial challenges faced by young women with breast cancer, they are also at a stage in life when a serious illness is not anticipated and the stress of cancer is concurrent with the many other life stresses associated with this stage in their lives [10, 13]. The specific issues for younger women include survival concerns for those who have young children, concerns about the loss of fertility due to premature menopause and early ovarian decline, body image and sexuality issues due to surgical alterations of the body and hormonal changes as a result of treatment, concerns about career and work as well as the fear of recurrence and uncertainty of the future [2, 3, 13]. In one study, the overall health-related quality of life decline in young women with breast cancer was twice as great as that of cancer-related losses in older women [22]. Further, treatment complications may involve side effects and physical sequelae, which may lead to “significant changes in family roles, employment problems, or other difficulties in personal and social functioning” [30].

Defining breast cancer rehabilitation

Cancer rehabilitation is broadly defined as the process of helping a patient obtain maximum restoration of physical, psychological, social, sexual, vocational, recreational, and economic functioning possible within the limits imposed by the disease and its treatment [9, 36]. It refers specifically to the interventions and services aimed at a survivor’s special needs post-diagnosis and post-treatment, with the aim of helping a person achieve the highest level of function, independence, and quality of life possible. Adjustment to the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer is a complex process that does not necessarily end at the completion of the acute treatment phase. Many physical, psychological, and social functional factors act differentially throughout the process and can unfold over a long period of time [38]. According to Johansen, “more than 50% of cancer patients may…have impairments or limitations which could potentially be improved by rehabilitative interventions” [19].

The specifics of what services should be included in rehabilitation programs are ill-defined. The services may include a broad range of activities such as physical rehabilitation, psychological support, counseling and information on lifestyle and behavior changes, financial counseling, and information on coping strategies to deal with the side effects and late effects of the treatment and other clinical issues [12, 16, 19, 24]. Ideally, all of these interventions and services should be tailored to the specific needs of each individual patient. Johansen argues that “apart from obvious gains for the patient, cancer rehabilitation can also be important in socio-economic terms by reducing pressure on health system resources and increasing the working population” [19].

Study aim

The overall goal of this study was to assess the rehabilitation needs and preferences of young women under the age of 50 with breast cancer in Atlantic Canada and to identify factors that may impact or prevent cancer rehabilitation utilization. This study protocol was reviewed by the Dalhousie University Research Ethics Committee (ref #2008-1828).

Methodology

Study methods

For this study, we used a qualitative grounded theory approach involving two telephone interviews. The purpose of grounded theory is to “generate or discover a theory, an abstract analytical schema of a phenomena” [8]. An open-ended interview schedule was designed to invite the participants to share their stories and to talk about rehabilitation services. We conducted a second interview at 6 to 8 months after the first interview [8]. The main reason for this approach was threefold: (1) to create rapport with the participants and to have them talk about their diagnostic and treatment experiences, (2) to verify data collected (to assess if the issues in the second interview were still recognizable by those who lived the experience), and (3) to discuss rehabilitation services in more specific detail [34]. The analysis in this paper is based on both interviews.

Study setting and population

Atlantic Canada is comprised of four provinces: Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland and Labrador. It is a unique geographical area with a largely rural and ethnically homogenous population while economically deprived compared to other areas in Canada. Atlantic Canada has a land mass similar to that of France with a combined population of under 2.5 million people, almost half (48%) of whom live in rural areas [27, 33]. Women in Atlantic Canada who have been diagnosed with breast cancer generally have access to prompt treatment even though in some cases they may have to travel substantial distances for care. This treatment is frequently provided in surgical, oncology, or radiation units across the provinces. Follow-up care may be provided by surgeons, oncologists, and/or family physicians [15, 37]; however, Atlantic Canada lacks comprehensive cancer rehabilitation programs such as the ones that are offered in other parts of Canada and in the USA [1, 28].

Inclusion criteria

Women in Atlantic Canada over the age of 18 and under the age of 50 who were pre-menopausal at the time of diagnosis were recruited 1–5 years after their breast cancer diagnosis. We acknowledge that men also develop breast cancer; however, we did not include them in this study due to the low incidence rate. The age category used to define “young” is somewhat arbitrary and extremely variable [25]. Many studies focus on biological markers such as menopause to determine a younger population, while statistical database references often vary the specific age limits. For the purpose of this study, we broadly focused on women who are under the age of 50, who were pre-menopausal before the cancer diagnosis, in order to keep it relevant to the majority of research articles in this area of study.

Recruitment

Recruitment advertisements and information about our study were sent out to all breast cancer patient navigators and oncology clinics in Atlantic Canada. The participants were also recruited through information posters at various public locations (i.e., grocery store bulletin boards, public libraries, gyms) and through online message boards, information bulletins, and radio interviews. The advertisements were also placed in free classified sections of community newspapers across Atlantic Canada. All young adult cancer and breast cancer-specific support groups and organizations were contacted and all agreed to assist with recruitment through the distribution of our study information to their members via e-newsletters or group meetings. The recruitment posters stated that we were looking for young breast cancer survivors under the age of 50 who were 1–5 years post-diagnosis to take part in our study looking at rehabilitation needs after breast cancer. Interested participants were advised to contact the study coordinator via e-mail or a toll-free phone number directed to a research office at the study center. The recruitment strategies targeted both rural and urban women in Atlantic Canada. Besides the inclusion criteria discussed above and the focus on geographic representation, no other inclusion/exclusion criteria were used.

Interviews

We conducted telephone interviews with 35 young female breast cancer survivors in Atlantic Canada between November 2008 and March 2010. Between 6 and 8 months after the first interview, a follow-up telephone interview was conducted. The duration of the first interviews ranged between 20 min to 2.5 h for an average of 50 min, while the second interview lasted on average 20 min. The interviews were conducted by the research coordinator and one of the study investigators (JE). After a participant had contacted the study staff regarding her willingness to participate in an interview, a consent form was forwarded to the potential participant for it to be reviewed. Before the telephone interview could commence, procedures for oral consent were followed. The interviewer asked the potential participant if they agreed to participate, if they agreed to have the telephone conversation audio-taped (if not, the interviewer would take notes), and if they agreed that portions of their interview could be used as direct unidentifiable quotes for report writing.

The purpose of the first interview was to contextualize the breast cancer experience, to document any post-treatment issues, and to assess the overall awareness of rehabilitative care. The questions focused specifically on the physical, psychological, social, financial, sexuality/fertility-related, and vocational challenges faced after acute treatment and the general help-seeking behavior to address these issues (i.e., “Have you experienced any physical issues since completing your breast cancer treatment? If you have had problems, did you get help for your problems? If yes, from/by whom or where? How difficult was it to find help? If no, is there any reason why you have not received help? Please describe in detail.”). During the follow-up interview, the participants were given a brief summary of the issues that they had previously discussed with the interviewer and were then asked if they had experienced any new challenges since the first interview. The participants were given a broad list of rehabilitation services (e.g., psychologist, physiotherapist, dietician, massage therapy) and were asked for each service whether or not it was ever offered to them, if they had ever used this service, if they felt they needed this service, and if they felt that they would use it if it were available. The participants were also asked about their awareness of these services in their area, affordability of services, and accessibility to rehabilitative care. The final part of the interview asked the participants to describe what services they felt were essential to rehabilitative care after breast cancer and any recommendations to improve care.

The interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed verbatim and checked for accuracy by the researchers. Transcripts were read holistically and then line by line in order to extract significant categories from the interviews; within each category, sub-categories were identified. This method of coding allowed the researchers to include the diversity of experiences of the young women with breast cancer [8]. Although the coding scheme was developed by the team, for consistency purposes, only two researchers coded the interviews. If new categories were identified, the team would discuss these and come to a consensus. The transcripts were entered into the qualitative data analysis software program NVivo for easy coding and retrieval.

Findings

Profile of study population

Overall, 41 women volunteered for the study. Two were over the age limit of 50 at the time of diagnosis and therefore were excluded from participation, and four could not be reached for a second interview. At the end of the first telephone interview, the participants were asked a number of socio-demographic questions (Table 1). The average age at the time of diagnosis was 40 years old, and the average age at the time of interview was 43. Just over half of the participants (51%) lived in a rural community (population of less than 10,000) and more than half (54%) had an annual family income of less than $30,000 per year. Although theme saturation of the data was achieved around interview 25, we decided to continue to recruit participants because we wanted to be sure that all provinces were represented in the research.

Major categories: systemic and personal barriers to rehabilitative care

Barriers to rehabilitation services emerged as an overarching theme from the data and were divided into two major categories: systemic and personal barriers. The systemic barriers were those that could be attributed at least in part to the structure of the social and medical systems, such as availability of services, accessibility issues, and affordability of rehabilitative care. The personal barriers related more to personal choice and circumstances, such as withdrawing from the health care system due to time constraints, appointment fatigue, acceptance of physical limitations, and not wanting to burden the system. Despite the fact that all of the young women interviewed in our study were experiencing some kind of physical or psychosocial issue due to breast cancer and/or its treatment, less than half had ever sought or received any assistance to address these issues.

Systemic barriers

The accessibility and availability of services emerged as significant barriers to receiving rehabilitative assistance. These issues related to either the lack of or limited services and resources available or the difficulty accessing the services that were offered, either due to cost of services, travel issues, or general difficulties in finding assistance and getting appointments. Many participants also felt that there was an overall lack of services, resources, and support addressing the specific needs of young women. Lack of services and resources was a particular challenge in rural areas of Atlantic Canada. Over half of the study sample (51%) lived in a rural area, which means that they had to travel for treatment and follow-up appointments with their physicians and for access to rehabilitation support and services. In some cases, this lead to transportation and financial challenges which would often result in a decision not to seek the needed and desired rehabilitation services. One rural participant, who was unable to receive rehabilitative care due to the lack of personal financial resources, described it as follows: “There are times where I have to travel to City X [to the nearest health centre] for my follow-up care with my oncologist… if you’re flying you’re looking at, at least 500 dollars umm if you’re going to take the bus you’re looking at an 8 hour bus ride and that’s, that’s going to run you about 250 dollars…” NF08.

Not only was the cost of travel a concern for many, but the expense of the rehabilitation services also posed a significant barrier to seeking such care. Many rehabilitative cancer services are not included in the basic Canadian Universal Health Insurance. In addition to the Universal Health Care Insurance, many Canadians are enrolled in a supplemental health insurance program. Almost all (94%) of the participants had supplemental health insurance. However, these supplemental health insurance policies often have severe restrictions on coverage and many rehabilitative services such as physiotherapy, counseling, or massage therapy are not covered or have limited coverage. Hence, many participants faced out-of-pocket expenses. One participant described her out-of-pocket expenses as follows: “I spent about $20,000 on getting myself better…primarily for massage therapy, lymphatic drainage, counseling and physiotherapy… items that are not covered under the medical system… Put it this way, the system would pay me to pop a pill to deal with the pain, but it would not pay me to rehabilitate my body and deal with the problem at its root” PE01. As another participant described: “It cost me a thousand dollars to get bras, a compression sleeve, a bathing suit and prosthesis one for swimming and one for everyday. It was a thousand dollars so that I could go out the door and lead a normal life…I couldn’t afford anything else” NB02.

In addition to affordability of rehabilitation services, many participants stated that they were unaware of rehabilitative services altogether. This lack of rehabilitative care awareness was twofold: some women believed that the problems experienced were normal and par for the course and were unaware that help was available, while others recognized the problem but were unaware of rehabilitative services in their region or did not know who to approach. Almost half of the participants stated that they did not receive any information regarding rehabilitative services at all after breast cancer treatment. One participant who suffered serious emotional distress described her experience as follows: “Nobody had discussed the emotional aspect of it at all, then as a result I thought that there was something wrong with me, that I was emotional about it all… I really, you know, in my heart, I feel that if I had, had the emotional support from a medical perspective right from the beginning that maybe I would not have ended up going down the road that I have ended up umm because you know in the end, I had nothing” NF02. As another participant summarizes: “…I didn’t feel at the time that I could get any help…no one ever really talked to me about it [rehabilitative care]” NS13.

Personal barriers

Even more significant than the systemic barriers to rehabilitative services after breast cancer were personal barriers. Several participants described being too busy trying to “get back to normal” and that they had to “catch up on all that they missed” to even think about seeking rehabilitation services. Often the choice not to seek services was related to family and household responsibilities. Many women felt that their family had sacrificed enough during their cancer treatments and they just did not want to take any more time or financial resources away from them to pursue rehabilitative support for their own needs. As one participant described: “I had to make a choice, I was either going to have to choose to go back and forth to City X whenever I wanted for my 6 weeks check up after my surgery and for everything else that I needed after that and then my kids wouldn’t get to participate in extracurricular activities at the level they had before I was diagnosed with cancer…I wasn’t going to have them sacrifice, not one minute what they were involved in…We, we were making too much [income] to access some programs that are available and we didn’t have enough…there wasn’t enough in the bank to, to you know to, so that I could go back for my 6 week check up or get help” NF08.

Some participants stated that they did not seek rehabilitative services for the problems they were facing due to cancer treatments because they were just too tired of going to medical appointments. As one participant described: “I just got fed up because, you know, your life becomes one big medical appointment or exercise regime or something, you know, it’s always something, always, always, always and you do get fed up with it” PEI02. Another participant felt that the rehabilitation service appointments were an added stress in her busy schedule and hindered her attempts to just “get back to normal”. She said: “I tried massage therapy …but I just couldn’t do it anymore because I just felt like I just couldn’t take any more appointments… I got tired of going to the hospital and sitting in somebody’s waiting room and I was just, I clamored to have my ‘whatever’ normal life I was going to get back. I just wanted to get it started. I’d had enough…It [rehabilitation services] becomes just one more thing that you have to get into your busy day” NBO1. For one participant, rehabilitation was just a reminder of the fact that she had cancer and therefore she did not want any more time for appointments to be taken away from her personal time. She said: “It [cancer] took enough of my time, so now it was time to do what I wanted to do [for recreation]” NS05.

For several participants, there was an acceptance of the limitations and challenges resulting from breast cancer treatments. They felt that this was their new reality. As one participant states: “I guess I just assumed this is something I’ll always have because I’ve had surgery there and I guess I just assume it’s not really bad, it’s just … well it’s just something I’ll have to live with. I just never, I guess I didn’t think it was something that would improve” NB13. Other participants just assumed that their symptoms post-treatment were normal. For example, one participant felt that her depression was a normal response to a cancer diagnosis and therefore she did not seek assistance. She said: “I think at the time I thought it [depression] was just a normal reaction to what was happening to me and professionally I didn’t feel that any, you know, anybody could help me. It was just something I had to go through and I’d get over it” NF01.

The perception of rehabilitative support and services available was a factor for many post-treatment care decisions. Some women felt that, because they were beyond the acute treatment phase of the disease, they did not have the right to access more services provided through the hospitals and cancer clinics. They discussed their concerns and inhibitions about seeking rehabilitative care, particularly psycho-social support, due to a fear of burdening the system, facing long wait times, or, alternatively, being reminded of the cancer. There was an underlying perception that the patients had to meet strict criteria to be considered for rehabilitative care, even if they were experiencing issues and challenges post-treatment. As one participant diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer and was recently diagnosed with lymphedema describes: “Unfortunately I haven’t been lucky enough to have traditional chemo and radiation and therefore I am not worthy (laughs) to be involved in some of these things [rehabilitation services]. This is how I’ve been made to feel [by health care professionals and other breast cancer survivors]. I have carried guilt because I’m not sick enough.” NB02. Another woman did not want to draw attention by wearing a rehabilitative compression sleeve on her arm for her lymphedema because it was viewed as a constant reminder of cancer.

She said: “I see people running around wearing sleeves that have no indication of lymphedema whatsoever. I’m thinking: Why are you doing that? How uncomfortable. How hot. It’s just like a big reminder. It’d just be like every day: I have cancer. I have cancer. I have cancer. You might as well tattoo it across your head as wear one of those darn-looking sleeves” NB12.

There was a significant variability among the rehabilitation needs and experiences of participants in relation to time post-diagnosis. Based on our data, the rehabilitation needs are dictated more by treatment intensity and life context (i.e., psychological impact, social support, work status, financial state) than time since diagnosis.

Discussion

Many studies have demonstrated that rehabilitation services are important for breast cancer patients and that these can help improve physical and mental health after treatment [2, 14, 20]. Our study shows that there are significant systemic barriers to receiving support post-treatment for young breast cancer survivors in Atlantic Canada. However, even more concerning are the personal barriers discussed which hinder rehabilitative care, particularly because young women can greatly benefit from these services given that they still may have many healthy years ahead of them. For the young women facing difficulties after treatment who did have available services and access to rehabilitative care, our results show that they may still chose not to utilize them due to a wide variety of personal factors. This concept of personal barriers to accessing rehabilitation services has not been extensively discussed in the literature.

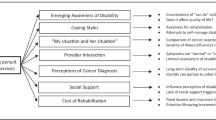

Based on our study results, we have developed a simple conceptual model to illustrate the hierarchy of existing barriers to rehabilitation services (Fig. 1). Each layer in this model represents a level of barriers which young women with breast cancer must overcome in order to access rehabilitative care services. The outer layer represents the systemic barriers to care that exist within the health care system such as the lack of services and/or accessibility to services (i.e., travel issues, lack of referrals), the lack of awareness of services, and/or the lack of personal financial resources to pay for rehabilitative care. Many women are unable to overcome these systemic barriers and therefore miss out on the much-needed assistance and support that may prove to be beneficial to their overall quality of life.

However, for those young survivors who had rehabilitation services and support offered and available to them, circumstances and personal choices added another dimension to the decision process and often created another layer of barriers that hindered the utilization of these rehabilitation services. The rehabilitative needs of the women in our study were often eclipsed by attitudes and responsibilities deeply rooted in their gender and domestic roles and responsibilities. In our sample, 83% were married or in a common-law relationship and 80% had children. Feelings of guilt and “not having been there” for the family during treatment were frequently discussed and often influenced the decision not to seek assistance after treatment. Other studies have examined the impact of breast cancer patients on family relationships. One study concluded that breast cancer can create tension in the lives of the partner and the demands of the family frequently outweigh the needs of the patient [11]. Semple and McCance [31] reviewed the literature, examining the impact on families when a parent is diagnosed with cancer. The literature indicated that women wanted to establish a “normal family routine” again as soon as possible [31]. Traditionally, women’s roles have been to care for the family and thus their lives tend to be embedded in the experiences and expectations of their partners and children, as well as by broader societal gender roles and expectations [26]. The results of our study are among the many that conclude that women’s caregiving roles can have serious implications on their overall health and well-being, with family responsibilities often taking priority over their own needs [11, 18, 26].

Revenson and Pranikoff present a conceptual framework for studying decision making among long-term breast cancer survivors, which is complementary to our barriers model. Their “Contextual Model for Treatment Decision Making” focuses on how psychological processes such as decision making are embedded within the socio-cultural, situational, interpersonal, and temporal contexts of people’s lives [29]. For the young women in our study, the socio-cultural context includes factors related to socio-economic status which may determine the affordability of services, education level, cultural background and perception of rehabilitation, or issues related to age and being young with cancer. The situational context includes those aspects of women’s lives which influence their immediate environment, such as child care responsibilities, time constraints to seek after-treatment care, work commitments, and the specific characteristics of the individual’s disease and treatment. The interpersonal context of women’s lives influences how they communicate and relate to others, particularly their health care providers. The amount, degree, and timing of information about rehabilitative care services are important in this context and how these can influence the awareness of challenges faced after breast cancer as well as the assistance available to cope with these challenges. The temporal context encompasses the timing of illness within the young women’s lives as well as the timing of any challenges faced after breast cancer treatment.

Having developed a better understanding of the barriers to cancer rehabilitation care, the subsequent issue is what can be done to reduce such barriers? Although a detailed set of recommendations are beyond the scope of this paper, the following actions would assist in the reduction of cancer rehabilitation barriers: health care professionals take a more proactive approach in recommending rehabilitative care after treatment, better health insurance coverage and/or financial assistance for rehabilitation services, improved communication between the various health care professionals, and, finally, more rehabilitation support for rural populations.

Conclusion

A considerable number of systemic and personal barriers to receiving rehabilitation post-treatment care exist for young breast cancer survivors in Atlantic Canada. Despite the fact that all of the young women interviewed in our study were experiencing some kind of physical or psychosocial issue due to breast cancer and/or its treatment, less than half had ever sought or received any assistance to address these issues. The systemic barriers can be reduced by introducing more services or financial assistance; however, the personal barriers to rehabilitation services are difficult to ameliorate due to the complex set of roles within and outside the family for this group of young breast cancer survivors.

Our research illuminates the experiences and contexts of young women’s lives and how these issues can have a substantial impact on their decisions to seek and receive rehabilitative care services after breast cancer treatment. These young women are more than just breast cancer survivors; they are also mothers, partners, caregivers, daughters, friends, and workers. Health care providers need to take into consideration the multiple contexts of women’s lives when developing and promoting breast cancer rehabilitation services and programs. Optimizing the psycho-social and physical outcomes for young breast cancer survivors through rehabilitation is essential as they potentially have many productive years ahead of them and may be able to contribute greatly to society.

Study limitations

Our study results are based on a relatively small theoretical sample and therefore the results cannot be generalized to all breast cancer patients. As in most research studies, particularly in self-referral studies such as this one, the participants who have experienced challenges (in this case, related to breast cancer treatment) may have been more inclined to participate than women who did not. Therefore, although we are able to describe in detail the types of challenges experienced and the rehabilitative care needs of young women after breast cancer, we cannot determine how common these problems are at post-treatment. However, we feel that we have identified a serious issue that requires further research to explore our theoretical model that breast cancer patients, based on their gender roles, will sacrifice rehabilitation services and treatments in order to “get back to normal” for their families.

References

Rejeneration: Mobile Cancer Rehabilitation (2011) http://rejeneration.ca/customized-cancer-rehabilitation-program. Accessed on March 31, 2011

Avis NE, Crawford S, Manuel J (2005) Quality of life among younger women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 23:3322–3330

Aziz NM (2007) Cancer survivorship research: state of knowledge, challenges and opportunities. Acta Oncol 46:417–432

Beattie A (2009) Detecting breast cancer in a general practice—like finding needles in a haystack? Aust Fam Physician 38:1003–1006

Bosompra K, Ashikaga T, O’Brien PJ, Nelson L, Skelly J (2002) Swelling, numbness, pain, and their relationship to arm function among breast cancer survivors: a disablement process model perspective. Breast J 8:338–348

Canadian Cancer Society’s Steering Committee (2010) Canadian cancer statistics 2010. Canadian Cancer Society, Toronto

Canadian Cancer Society’s Steering Committee (2007) Canadian cancer statistics 2007. Canadian Cancer Society, Toronto

Creswell JW (1997) Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five traditions. Sage, London

DeLisa JA (2001) A history of cancer rehabilitation. Cancer 92(Suppl):970–974

Dunn J, Steginga SK (2000) Young women’s experience of breast cancer: defining young and identifying concerns. Psychooncology 9:137–146

Fitch MI, Allard M (2007) Perspectives of husbands of women with breast cancer: impact and response. Can Oncol Nurs J 17:66–78

Fors EA, Bertheussen GF, Thune I, Juvet LK, Elvsaas IK, Oldervoll L, Anker G, Falkmer U, Lundgren S, Leivseth G (2010) Psychosocial interventions as part of breast cancer rehabilitation programs? Results from a systematic review. Psychooncology. doi:10.1002/pon.1844

Ganz PA, Greendale GA, Petersen L, Kahn B, Bower JE (2003) Breast cancer in younger women: reproductive and late health effects of treatment. J Clin Oncol 21:4184–4193

Gerber LH (2001) Cancer rehabilitation into the future. Cancer 92:975–979

Grunfeld E (2009) Optimizing follow-up after breast cancer treatment. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 21:92–96

Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E (2006) From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition. National Academies, Washington, DC

Hurny C, Bernhard J, Coates AS, Castiglione-Gertsch M, Peterson HF, Gelber RD, Forbes JF, Rudenstam CM, Simoncini E, Crivellari D, Goldhirsch A, Senn HJ (1996) Impact of adjuvant therapy on quality of life in women with node-positive operable breast cancer. International Breast Cancer Study Group. Lancet 347:1279–1284

Jenkins CL (1997) Women, work, and caregiving: how do these roles affect women’s well-being? J Women Aging 9:27–45

Johansen C (2007) Rehabilitation of cancer patients—research perspectives. Acta Oncol 46:441–445

Johnsson A, Tenenbaum A, Westerlund H (2011) Improvements in physical and mental health following a rehabilitation programme for breast cancer patients. Eur J Oncol Nurs 15(1):12–15

Kornblith AB, Powell M, Regan MM, Bennett S, Krasner C, Moy B, Younger J, Goodman A, Berkowitz R, Winer E (2007) Long-term psychosocial adjustment of older vs younger survivors of breast and endometrial cancer. Psychooncology 16:895–903

Kroenke CH, Rosner B, Chen WY, Kawachi I, Colditz GA, Holmes MD (2004) Functional impact of breast cancer by age at diagnosis. J Clin Oncol 22:1849–1856

Luker KA, Beaver K, Leinster SJ, Owens RG (1996) Meaning of illness for women with breast cancer. J Adv Nurs 23:1194–1201

Lundgren H, Bolund C (2007) Body experience and reliance in some women diagnosed with cancer. Cancer Nurs 30:16–23

Miedema B, Hamilton R, Easley J (2007) From “invincibility” to “normalcy”: coping strategies of young adults during the cancer journey. Palliat Support Care 5:41–49

Moen P, Robinson J, Dempster-McClain D (1995) Caregiving and women’s well-being: a life course approach. J Health Soc Behav 36:259–273

Mongabay World Statistics (2011) http://www.mongabay.com/igapo/world_statistics_by_area.htm. Accessed on March 31, 2011

National Rehabilitation Hospital (2011) Breast cancer rehabilitation. http://www.nrhrehab.org/Patient+Care/Programs+and+Service+Offerings/Outpatient+Services/Service_Page.aspx?id=10. Accessed on March 31, 2011

Revenson TA, Pranikoff JR (2005) A contextual approach to treatment decision making among breast cancer survivors. Health Psychol 24:S93–S98

Ronson A, Body JJ (2002) Psychosocial rehabilitation of cancer patients after curative therapy. Support Care Cancer 10:281–291

Semple CJ, McCance T (2010) Parents’ experience of cancer who have young children: a literature review. Cancer Nurs 33:110–118

Shannon C, Smith IE (2003) Breast cancer in adolescents and young women. Eur J Cancer 39:2632–2642

Statisics Canada (2009) Population urban and rural by province and teritory. Available from http://www40.statcan.ca/l01/cst01/demo62a-eng.htm. Accessed on March 31, 2011

Thibodeau J, MacRae J (1997) Breast cancer survival: a phenomenological inquiry. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 19:65–74

Thomas-MacLean R, Miedema B, Tatemichi SR (2005) Breast cancer-related lymphedema: women’s experiences with an underestimated condition. Can Fam Physician 51:246–247

Thomas DC, Ragnarsson KT (2009) Principles of cancer rehabilitation medicine. In: Hong WK, BastJr RC, Hait WN, Kufe DW, Pollock RE, Weichselbaum RR, Gansler TS, Holland JF, Frei E III (eds) Holland-Frei cancer medicine. People’s Medical, Shelton, CT

Vanhuyse M, Bedard PL, Sheiner J, Fitzgerald B, Clemons M (2007) Transfer of follow-up care to family physicians for early-stage breast cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 19:172–176

Wenzel LB, Fairclough DL, Brady MJ, Cella D, Garrett KM, Kluhsman BC, Crane LA, Marcus AC (1999) Age-related differences in the quality of life of breast carcinoma patients after treatment. Cancer 86:1768–1774

Yankaskas BC (2005) Epidemiology of breast cancer in young women. Breast Dis 23:3–8

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Naomi Tschirhart, Tashina Van Vlack, and Miles Clayden for their assistance with this project. Financial support for the study was provided by the Canadian Breast Cancer Foundation—Atlantic Chapter.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Miedema, B., Easley, J. Barriers to rehabilitative care for young breast cancer survivors: a qualitative understanding. Support Care Cancer 20, 1193–1201 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-011-1196-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-011-1196-7