Abstract

Purpose

There is growing evidence in psycho-oncology that people can experience posttraumatic growth (PTG), or positive life change, in addition to the distress that may occur after a cancer diagnosis. Many studies utilise existing PTG measures that were designed for general trauma experiences, such as the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory. However, such inventories may not take into account life changes associated with a crisis specifically in a health-related context.

Method

The current study presents a mixed method exploration of the post-diagnosis experience of cancer survivors (N = 209) approximately 3 years after diagnosis.

Results

Quantitative and qualitative assessment of PTG showed that appreciating life was the most salient area of positive life change for cancer survivors. The results also revealed that in addition to several PTG domains captured by existing quantitative PTG measures, further positive life changes were reported, including compassion for others and health-related life changes.

Conclusions

These domains of PTG highlight the unique context of a cancer diagnosis and the potential underestimation of positive life change by existing inventories. Further research is warranted that is directed towards designing a context-specific PTG measure for cancer survivors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Psychosocial adjustment to cancer can be viewed as a dynamic psychosocial process that occurs over time as the person is confronted with the multitude of changes elicited by the cancer and subsequent treatments [1]. In this view, rather than appraising cancer purely as a stressor, a diagnosis can be viewed as a catalyst for life change, with both negative and positive repercussions [1]. A growing body of research is providing evidence for positive life changes, or posttraumatic growth (PTG), that can be experienced, alongside post-diagnosis distress, by both the patients and their carer. Existing PTG measures that were designed for general trauma experiences are currently used in studies with cancer survivors [2, 3]. However, these measures do not necessarily assess life changes that may be unique to a health-related context. The current study proposes to address this gap in the literature by identifying the types of positive life change reported by cancer survivors that may differ from those reports not related to personal health issues.

A diagnosis of cancer and associated treatments may represent a potentially ongoing threat and trigger recurring challenges [1, 4]. This may be different from other traumatic experiences that are marked by discrete events occurring in the past, such as witnessing a fatal vehicle accident. With the cancer experience, there may not be a clear delineation between the traumatic event and the aftermath of trauma as the diagnosis, treatment, and potential for recurrence constitutes an ongoing and long-term process [5]. A diagnosis of a life-threatening illness may also be unique from some other types of traumatic events as it may raise personal concerns for the person diagnosed with cancer, such as mistrust of their body’s physical integrity or feeling a lack of control over their body’s functioning [4, 6]. The complex array of post-diagnosis events and the shifting nature of stressors for cancer survivors result in a distinctive population in which to examine the concept of posttraumatic growth and the types of positive life change that are recurrent in this context [4].

The emergence of quantitative studies assessing PTG after a diagnosis of cancer in the last decade has strengthened earlier anecdotal evidence and qualitative psycho-oncology research showing positive life change. In a review of PTG quantitative research with cancer survivors, Stanton et al. [7] suggest that reporting PTG after a diagnosis is highly prevalent, and the types of life changes commonly reported by cancer survivors include strengthened relationships, increased appreciation of life, and enhanced spirituality. The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) [8] is one of the most widely used quantitative measures of growth [9]. The PTGI is a multidimensional measure of positive post-trauma (e.g. [2, 10]) assessing personal strength, relating to others, appreciation of life, new possibilities, and spiritual change. The other commonly used measure in studies of cancer survivors to assess positive life change is the Benefit Finding Scale (BFS) [11], which was validated with women diagnosed with breast cancer. The BFS is unidimensional with positive change represented as a total score. Problematically, the BFS and PTGI do not contain items relating to themes that have recently been identified in qualitative research as being relevant to post-diagnosis PTG with cancer survivors, such as health-related changes.

In a review of qualitative research in illness settings, Hefferon et al. [12] emphasise the distinctive nature of PTG after a diagnosis of a life-threatening illness compared with other experiences such as bereavement. The review predominantly contained studies of cancer patients, but other studies discussed included people who had HIV, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, stroke, and heart disease diagnoses. Hefferon et al. suggest that many people reported their illness as an event that enriched their lives and that they did not regret that it happened. The unique challenges associated with being diagnosed with a life-threatening illness can be catalysts for particular life changes, such as taking responsibility and monitoring one's own health, listening to one's own body, improved health behaviours and health checks, cessation of risky behaviours, and a positive identification with one's own body [12]. Qualitative studies of women diagnosed with breast cancer [11] and people diagnosed with multiple sclerosis [13] have revealed PTG themes such as health behaviour change, helping others, learning more about the disease, becoming aware of one's own health, and re-evaluating lifestyle and diet. Calhoun and Tedeschi's [14] model of PTG encompasses changes in perception of self which can lead into a new narrative and gained wisdom. Health-related behavioural change and an awareness of health and body can be perceived as falling within this realm of improved self-perception. To date, these are areas of positive life change that have not yet been examined in existing measures of PTG.

Rationale and aims

Growing evidence from qualitative research indicates that domains such as health-related life change and awareness of body are important constructs that embody posttraumatic growth after a diagnosis of a major illness (e.g. [12, 13]). Health-related life change is not currently assessed in any measure of PTG or benefit finding. These types of positive life changes can be encompassed in Calhoun and Tedeschi's [14] model of PTG, yet current standardised measures of PTG may underestimate positive life change in this context as the measures are not entirely relevant to the post-diagnosis experience of cancer survivors. The purpose of the current study was to conduct a large-scale mixed methods study of cancer survivors to ascertain the salience and prevalence of different PTG domains with cancer survivors. PTG will be assessed via a quantitative measure and written narratives of the participant's cancer experience. Through these narrative data, it is anticipated that other PTG domains, not measured in existing inventories, would be identified that may be unique to an illness context.

Method

Participants

Three hundred and thirty-five participants (35% response rate) were recruited through a cancer treatment clinic in a regional hospital in Australia. Of these participants, 209 (62.4%) responded to the qualitative component of the study by providing written narratives. On average, the 209 participants were 2.90 years (SD = 1.86) post-diagnosis, had a mean age of 62.99 years (SD = 12.23), were predominantly married (75%), no longer had cancer (70%), and were no longer receiving treatment (75%). Cancer diagnoses were grouped into major categories in consultation with the oncologists at the clinic, with the major diagnoses being breast (34%), prostate (15%), haematological (13%), and colorectal (9%). A more detailed examination of the study participants is provided elsewhere [15].

Procedure

This research was conducted in accordance with APA ethical standards with ethics approval obtained at the University of Tasmania prior to study commencement. The clinic posted a survey package to every person treated for cancer at the clinic across a 2-year period. Participants gave informed consent to take part in the study by returning their completed survey.

Quantitative measures and analyses

The survey included questions regarding demographic information (age, gender, relationship status, ethnicity, and area lived in); disease-related characteristics (type of diagnosis, time since diagnosis, current cancer, and treatment status); and the PTGI [8]. The PTGI contains 21 items asking participants to indicate the degree to which each statement had occurred in their life as a result of being diagnosed with cancer (e.g. “I discovered that I’m stronger than I thought I was”). Inventory subscales describe positive life change in domains of relationships with others, personal strength, new possibilities, appreciation of life, and religious/spiritual change. Items are rated on a six-point Likert scale from 0 to 5 (not at all to very great degree). Strong internal consistency has been found for the PTGI total score and subscale scores in previous research with cancer survivors (e.g. [16]) and was replicated in the current study (α = 0.90 for total PTGI score and ranging from α = 0.81 to 0.89 for subscale scores).

Statistical analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 14.0). Initial quantitative analyses were conducted to determine any differences between participants who responded to the narratives and those participants who only completed the quantitative measures. This was done via chi-square analyses to assess significant differences in frequencies on categorical variables (gender, relationship status, ethnicity, area lived, cancer-related variables) and via independent samples t tests for continuous variables (age, time since diagnosis, PTGI scores). After assessing potential differences in means and frequencies, all analyses were conducted on the final sample of participants who responded to the qualitative component of the study (N = 209).

Qualitative research approach

Written narratives were used to explore the individual’s perception of their diagnosis of cancer and how they dealt with the challenges associated with this experience. Space was provided in the survey inviting participants to tell their story with the following instructions: Please feel free to add any comments that relate to the way in which you are dealing with (or have dealt with) being diagnosed with cancer or to the changes in your life that may have happened since your diagnosis. Your comments are greatly appreciated in assisting us to understand the ways in which people adjust after a diagnosis of cancer. Written narratives to an open-ended question allowed the participant to tell the story of their experience and respond in a thoughtful and measured manner, which may differ from an interview format. That is to say, the written narrative was not time specified so the participants had as much time to contemplate their responses as they wanted. This type of naturalistic inquiry is also free from the potential of interviewer influence in so much as an interviewer may subtly and/or inadvertently guide responses.

Qualitative data were investigated using thematic analysis based on an interpretative phenomenological framework that has been used extensively in health psychology research [17]. Thematic analysis involves becoming thoroughly familiar with the transcripts and examining similarities and contrasts in themes across the written accounts [18]. Concepts were noted in each case and emergent themes identified by grouping similar concepts. Prior theory serves as a resource for the interpretation of themes; however, thematic analysis also promotes the uncovering of novel themes [17]. Themes that were identified later in the process were coded in earlier narratives through a continual reviewing process.

Reliability and validity of qualitative data

A rigorous approach to qualitative analysis was achieved through several means, including the large representative sample, triangulation of data sources, and analysis through NVivo (version 7). Whilst the use of a qualitative analysis computer programme does not replace reading and manual coding of themes, a computer programme helps ensure rigour in the analytic process [19]. This system provides a framework to keep concepts and themes organised and is a thorough approach to the ongoing process of qualitative analysis [19]. Text searches in NVivo and matrix queries that triangulated qualitative and quantitative data allowed for an auditing process of the emergent themes to ensure reliability of the data and enhance credibility and internal validity of the data [20].

Results

Descriptives

Two hundred and nine of the 335 participants responded with a narrative of their cancer experience (62.4% of the entire sample). Initial analyses determined that participants who wrote a narrative did not significantly differ on individual factors, disease factors, or PTGI scores compared with participants who only completed the quantitative assessment. Chi-square analyses showed that the frequency of those who responded to the qualitative component of the study did not differ from the other participants by gender [χ 2(1, N = 335) = 0.66, p = 0.42]; relationship status [χ 2(1, N = 334) = 0.65, p = 0.42]; ethnicity [χ 2(1, N = 323) = 1.55, p = 0.21]; area lived in [χ 2(1, N = 329) = 1.70, p = 0.19]; current cancer status [χ 2(2, N = 326) = 1.37, p = 0.50]; or were currently undergoing treatment [χ 2(1, N = 328) = 0.78, p = 0.38]. When exploring whether the four major cancer diagnoses of breast, prostate, colorectal, and haematological cancer survivors differed in providing narratives, chi-square analysis revealed no differences between the diagnosis groups [χ 2(3, N = 235) = 2.61, p = 0.46]. Independent samples t tests showed that participants who provided narratives did not differ in age [t(269) = −0.45, p = 0.65]; time since diagnosis [t(276) = 0.19, p = 0.85]; or PTGI scores [t(324) = 1.41, p = 0.16] compared with the participants who did not provide qualitative data.

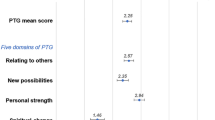

The level of positive life change, as represented by the PTGI mean (M = 60.99, SD = 23.35), is comparable to previous cross-sectional PTG research using this inventory with cancer survivors (e.g. [3, 21]). Examination of PTGI minimum scores revealed that the majority of participants (99% of the sample) indicated that positive life change had occurred. The PTGI subscale item means show that participants endorsed appreciation of life (M = 3.59) as the most important area of positive life change, followed by relating to others (M = 3.29), personal strength (M = 3.23), new possibilities (M = 2.10), and religious/spiritual change (M = 1.87). The item “Appreciating every day” had the highest item mean, with 82.4% of the sample rating this item as 3 or above on the 0–5 Likert scale (greater than a moderate degree). This was closely followed by the item “Knowing that I can count on people in times of trouble” with 81.5% of the sample rating this item as 3 or above.

Qualitative themes

The narrative data comprised a wide variety of themes including positive life changes that were reported by 44% of the sample. The PTG themes reported by participants included: engaged in and appreciating life, personal strength, health-related benefits, compassion for others, strengthened relationships, and priorities (see Table 1 for quotes relating to each PTG theme).

Similarities between several of these PTG component themes and the domains of the PTGI are evident, with the exception of a lack of religious or spiritual growth by any participant and the addition of health-related benefits and compassion for others. Whilst participants reported utilising their faith in God or spiritual beliefs as a coping resource from which to draw strength during their cancer experience, enhanced or newfound faith/spirituality was not expressed.

The domains of PTG strongly endorsed in the current study but not emphasised in the PTGI included increased compassion for others and health-related benefits. Compassion towards others that was expressed in the narratives described participants' empathy for other people who were struggling with similar adversities. Participants reported that this newfound compassion resulted from their own diagnosis and treatment experience. Reports of compassion ranged from a deeper understanding of others' experiences to supportive acts displayed by the participant. For example:

To help my fellow beings on my demise I donated my body to the body bequest program hoping they will discover something from my condition. (Participant no. 105)

[I now] have great empathy and understanding of how others feel when given a diagnosis of cancer. (Participant no. 223)

I am a member of the Breast Cancer Network and am able to offer advice and help to other women. This I find is my chance to give back what I was given and what a gift. (Participant no. 242)

The health-related benefits evident in the current study included lifestyle changes incorporating improved diet and increased exercise. Two participants with prostate cancer described radical life changes involving moving to another country to adopt an Asian lifestyle and diet in order to reduce their prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels, which can be used as a marker for prostate cancer. The participants detailed changes that had been made with diet and reducing stress in order to assist healing and recovery. Whilst other health-related benefits described by participants were not as extreme as relocating to another country, improved health behaviour and cessation of risky behaviours were prominent themes in this study. For example, participant no. 46 wrote of her health-related benefits after her diagnosis of cervical cancer:

I now am very healthy, exercise regularly, eat healthy and try to encourage those around me to do the same.

Other participants describe more detailed changes in their health behaviours since their cancer diagnosis; for example, participant no. 327 reported:

I changed my diet to totally pure organic food, nothing processed at all. I got my mercury fillings from my teeth removed by a special dentist. I went through a detoxification process for one week.

Reported examples of compassion for others and health-related benefits can be found in Table 2.

Although the current study focused on positive life change after a cancer diagnosis, the survey instructions asked participants about life changes and did not specify whether these changes were positive or negative. A small minority (1.19%) stated that they felt defeated by their cancer and could not perceive any benefit from their experience, as exemplified by participant no. 179 who wrote:

Cancer sucks! There are no good things about it and it is so unfair.

More commonly, participants reported positive life changes in addition to adverse outcomes. The negative effects of diagnosis and treatment of cancer that participants reported included triggered intrusive rumination about their cancer, long-term physical and psychological repercussions, and fear of recurrence. These adverse aspects of their experience were often reported in conjunction with positive life changes and were not discussed in contradiction to PTG.

Discussion

The results of this study provide an overview of PTG reported by cancer survivors in Australia approximately 3 years after being diagnosed. The majority of participants reported PTG, and inventory means were comparable to previous studies conducted with cancer survivors [3, 21]. The number of different domains of positive life change reported in the qualitative component highlights the multidimensionality of PTG and supports the relevance of some PTGI subscales for cancer survivors, including relating to others, new possibilities, personal strength, and appreciation of life. Both the qualitative and quantitative assessment of PTG revealed that appreciation of life was the most salient area of positive life change for cancer survivors; relating to others and personal strength were also shown to be important domains. The qualitative data revealed the prominence of compassion for others and health-related benefits. These PTG domains provide support for previous research in illness contexts, suggesting that some positive life change experienced after cancer may be unique to this context [12]. Existing PTG inventories may not contain items that are relevant to the post-diagnosis experience of cancer patients [2]. The measures used to assess positive life change with cancer survivors are predominantly the PTGI [8] and the BFS [11]; however, items relating to health-related life change are not included in either inventory.

The salience and variety of health-related benefits described by cancer survivors in the current study indicate the importance of this construct in the post-diagnosis experience. Health-related benefits described by participants included an improved diet, physical fitness (sport and exercise), accessing natural therapies, increased body awareness, regular medical checkups, meditation, adherence to treatment, and cessation of risky behaviours (e.g. smoking cessation). Improvement of health behaviours can be seen as taking responsibility for one’s own health and placing a heightened importance on the body, which is particularly pertinent in the context of cancer treatment [12].

Increased compassion for others is a concept included in some measures of PTG; however, the salience of this construct for cancer survivors is not captured well by existing inventories. For example, the PTGI contains only one item (“Having compassion for others”) regarding compassion that loads onto the relating to others subscale. Studies that have examined the PTGI domain structure in different cultural contexts such as Australia [10] show variations in how the single compassion item loads onto a different subscale, thus suggesting that the perception of a newfound compassion for others may be expressed differently across cultural contexts. Increased compassion for others has been strongly endorsed in other qualitative Australian research [22] and is commonly exemplified as a new awareness of others' experiences, a desire to help others, and participating in volunteer work [12]. The strength of this theme and possible cultural variation in perceived growth suggested in previous Australian research [23] provide support that the PTG domain of compassion for others needs to be clarified and enhanced in future research.

The current study also highlighted the absence of religious or spiritual change that is assessed by the PTGI. The tendency for Australian participants to report positive life changes in domains such as an increased compassion towards others, relating to others, appreciation of life, and personal strength, but not in religious or spiritual growth, is evidenced by a number of studies in general trauma and illness settings [e.g. 10, 24]. Whilst previous studies have found religious and spiritual growth to be a strongly endorsed area of positive life change, particularly following a diagnosis of a life-threatening illness [3], it may be that Australians have a more secular nature than people in the USA, where a large proportion of PTG research has been conducted [23]. The current study's observation of Australians' tendency to not endorse the PTGI subscale of spiritual or religious growth is consistent with emerging research investigating the influence of the respondent’s culture on the perception of PTG [25].

Limitations, strengths, and implications

Written narratives allowed participants to reflect on their cancer experience. Although this form of data collection permits a contemplative response, this method of data collection may also induce a limited response from the participant that cannot be expanded upon through further questioning. The means of qualitative data collection provided a rich source of data. However, it is acknowledged that within a phenomenological framework, in-depth interviews may have facilitated a more comprehensive investigation of posttraumatic growth after cancer [20]. Also, the retrospective nature of cross-section design generates customary limitations, such as memory bias undermining the accuracy and amount of information that is recalled and reported [26]. Elements such as cancer incidence, mortality, and survival rates provide the environmental context in which the individual appraises and manages their diagnosis and treatment. The participants in the current study predominantly identified themselves as Anglo-Australians and were married or in long-term relationships. Therefore, it is important to consider the current study’s results in the context that they were investigated in and apply caution when interpreting these findings in other countries, cultural environments, or with minority groups (in Australia and elsewhere).

The findings of several additional PTG themes shown in the current study of Australian cancer survivors, in addition to other PTG research in illness-related settings [12] and in Australia [23], reiterate the need to be context-specific when considering applications of research. Although it may be impractical to design an inventory appropriate to assess PTG after every type of traumatic event, the limitations of using a measure designed in a general trauma population with cancer survivors cannot be ignored. The high prevalence of cancer and increasing chances for surviving a diagnosis [27] highlight the importance of research that identifies factors that can be implemented in service delivery when providing post-diagnosis care.

The potential underestimation of PTG, as measured by existing inventories, impacts cross-study comparisons and highlights the unique experience after different types of trauma. The emphasis on health-related life change and compassion by cancer survivors shapes potential interventions that could address the promotion of PTG. To date, there appears to be no published research that has investigated PTG interventions in any context. The results of the current study suggest that future research on PTG interventions could target areas specific to the type of traumatic event experienced. Further studies can explore the impact that PTG domains, such as health-related benefits, have on long-term outcome for cancer survivors.

By broadening the knowledge base regarding PTG reported by cancer survivors, we can potentially increase our understanding of interventions that aim to enhance personal growth and tailor them to meet the specific needs of the post-diagnosis cancer experience. The diagnosis of a life-threatening illness such as cancer has the potential to create a number of health-related benefits and a newfound compassion for others. Identification of health behaviours and life changes specific to the cancer experience enables us to design interventions that aid the process of adjustment and increase the long-term well-being of cancer survivors [28]. Also, the potential for cultural influences on domains of PTG may have implications for promoting personal growth in clinical practice. Australians' tendency to not endorse the PTGI subscale of spiritual or religious growth is consistent with emerging research investigating the influence of distal culture on the perception of PTG [25]. This highlights the multidimensional nature of positive life changes and indicates that a different intervention approach may need to be considered [23].

Conclusion

PTG is a multidimensional construct that incorporates a number of different life changes for those diagnosed. The domains of positive life change reported by the cancer survivors in this study may reflect a cultural influence, in addition to the type of PTG likely to be perceived in an illness context. In particular, being diagnosed with cancer instigated a number of health-related benefits for many participants, including an improved diet, increased exercise, and safety conscious behaviour at work. Also, cancer survivors expressed a newfound compassion for others after facing the challenges of their own diagnosis. The PTG domains of compassion for others and health-related benefits can be encompassed within Calhoun and Tedeschi's model of PTG, yet the emphasis placed on these types of life changes after being diagnosed with cancer suggests that PTG may manifest itself differently for the cancer survivor. The participants reporting PTG stated that their reported positive life change might not have happened if their life had not been interrupted by their diagnosis. Therefore, future research can design and validate a measure of PTG that is relevant to the post-diagnosis experience of cancer survivors.

References

Brennan J (2001) Adjustment to cancer—coping or personal transition? Psycho-Oncology 10:1–18. doi:10.1002/1099-1611(200101/02)10:1<1::AID-PON484>3.0.CO;2-T

Ho SMY, Chan CLW, Ho RTH (2004) Posttraumatic growth in Chinese cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncol 13:377–389. doi:10.1002/pon.758

Cordova MJ, Giese-Davis J, Golant M, Kronenwetter C, Chang V, Spiegel D (2007) Breast cancer as trauma: posttraumatic stress and posttraumatic growth. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 14:308–319. doi:10.1007/s10880-007-9083-6

Kangas M, Henry J, Bryant R (2002) Posttraumatic stress disorder following cancer: a conceptual and empirical review. Clin Psychol Rev 22:499–524. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(01)00118-0

Tedeschi R, Calhoun L (2006) Posttraumatic growth in clinical practice. In: Calhoun L, Tedeschi RG (eds) Handbook of posttraumatic growth: research and practice. Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah, pp 291–310

Lin C-C, Tsay H-F (2005) Relationships among perceived diagnostic disclosure, health locus of control, and levels of hope in Taiwanese cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology 14:376–385. doi:10.1002/pon.854

Stanton AL, Bower JE, Low CA (2006) Posttraumatic growth after cancer. In: Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG (eds) Handbook of posttraumatic growth: research and practice. Lawrence Erlbaum, New Jersey, pp 138–175

Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG (1996) The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J Trauma Stress 9:455–471. doi:10.1002/jts.2490090305

Linley P, Andrews L, Joseph S (2007) Confirmatory factor analysis of the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory. J Loss Trauma 12:321–332. doi:10.1080/15325020601162823

Morris BA, Shakespeare-Finch J, Rieck M, Newbery J (2005) Multidimensional nature of posttraumatic growth in an Australian population. J Trauma Stress 18:575–585. doi:10.1002/jts.20067

Tomich PL, Helgeson VS (2004) Is finding something good in the bad always good? Benefit finding among women with breast cancer. Health Psychol 23:16–23. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.23.1.16

Hefferon K, Grealy M, Mutrie N (2009) Post-traumatic growth and life threatening physical illness: a systematic review of the qualitative literature. Br J Health Psychol 14:343–378. doi:10.1348/135910708X332936

Pakenham KI (2007) The nature of benefit finding in multiple sclerosis (MS). Psychol Health Med 12:190–196. doi:10.1080/13548500500465878

Calhoun L, Tedeschi R (2006) The foundations of posttraumatic growth: an expanded framework. In: Calhoun L, Tedeschi RG (eds) Handbook of posttraumatic growth: research and practice. Lawrence Erlbaum, New Jersey, pp 3–23

Morris BA, Shakespeare-Finch J (2010) Rumination, posttraumatic growth, and distress: Structural equation modelling with cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncol. doi:10.1002/pon.1827

Sears S, Stanton A, Danoff-Burg S (2003) The yellow brick road and the emerald city: benefit finding, positive reappraisal coping, and posttraumatic growth in women with early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychol 22:487–497. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.487

Riessman CK (2008) Narrative methods for the human sciences. Sage, Los Angeles

Thomas RM (2003) Blending qualitative and quantitative research methods in theses and dissertations. Corwin Press, Thousand Oaks

Bazeley P (2007) Qualitative data analysis with NVivo. Sage, Los Angeles

Lincoln YS, Guba EG (1985) Naturalistic inquiry. Sage, Los Angeles

Lechner SC, Zakowski SG, Antoni MH, Greenhawt M, Block K, Block P (2003) Do sociodemographic and disease-related variables influence benefit-finding in cancer patients? Psycho-Oncology 12:491–499. doi:10.1002/pon.671

Shakespeare-Finch JE, Copping A (2006) A grounded theory approach to understanding cultural differences in posttraumatic growth. J Loss Trauma 11:355–371. doi:10.1080/15325020600671949

Shakespeare-Finch J, Morris BA (2010) Posttraumatic growth in Australian populations. In: Weiss T et al (eds) Posttraumatic growth and culturally competent practice: lessons learned from around the globe. Wiley, New York

Carboon I, Anderson VA, Pollard A, Szer J, Seymour JF (2005) Posttraumatic growth following a cancer diagnosis: do world assumptions contribute? Traumatology 11:269–283. doi:10.1177/153476560501100406

Copping A, Shakespeare-Finch J, Paton D (2008) Modelling the experience of trauma in a white-Australian sample. Proceedings of the Australian Psychological Society 43rd Annual Conference, Hobart, Australia

Sica G (2006) Bias in research studies. Radiology 238:780–789

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2007) Cancer in Australia: an overview 2006 (Cancer Series No. 37). AIHW, Canberra, Australia

Connor M, Norman P (1996) The role of social cognition in health behaviours. In: Connor M, Norman P (eds) Predicting health behaviour. Open University Press, Buckingham, pp 1–22

Acknowledgements

The authors are appreciative to the WP Holman Clinic at the Launceston General Hospital, Tasmania for their assistance in this project. We especially thank Dr Kim Rooney and Ms Loris Towers. We also express gratitude to the participants for their overwhelming and supportive response.

Conflicts of interest

There is no conflict of interest between the authors and any funding bodies that would have a direct bearing on this article. The corresponding author has full control of all data relating to this article and would allow the journal to review this data if requested.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Morris, B.A., Shakespeare-Finch, J. & Scott, J.L. Posttraumatic growth after cancer: the importance of health-related benefits and newfound compassion for others. Support Care Cancer 20, 749–756 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-011-1143-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-011-1143-7