Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to identify the psychosocial needs of young people (12–24 years) who have a parent with cancer and to assess whether these needs are being met. This paper also presented the initial steps in the development of a need-based measure—the Offspring Cancer Needs Instrument (OCNI).

Methods

Study 1 used qualitative methods to identify the needs of the target population, including a focus group (n = 6), telephone interviews (n = 8) and staff survey (n = 26). In study 2, a quantitative survey design was employed where 116 young people completed the 67-item OCNI and either the total difficulties score of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ-TD; 12–17-year-old) or Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scale—21 (DASS-21) (18–24-year-old). Tests of reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) were used to assess the properties of each domain, where a level of 0.70 was deemed satisfactory as per scale guidelines. Construct validity was assessed by testing the proposed relationship between unmet needs and functioning where a coefficient of 0.03 was deemed satisfactory.

Results

The qualitative data yielded eight need domains (information, peer support, feelings, carer support, family, school/work environment, access to support and respite and recreation), which were subsequently used to inform the item content of the OCNI. The survey data revealed that 90% of young people endorsed 10 or more needs, and nearly a quarter indicated >50 needs. It was also found that these needs often go unmet: 87% of the participants had at least one unmet need, 43% reported >10 and just under a quarter had >20 unmet needs. The two highest reported unmet needs related to understanding from friends and assistance with concentrating and staying on task. The OCNI exhibited face and content validity and acceptable reliability for most of the domains. Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.64 (access to support) to 0.92 (information). Preliminary construct validity was assessed through the hypothesised positive relationship between unmet needs and the SDQ-TD for 12–17-year-old participants (r = 0.33, p<0.001) and the DASS-21 for 18–24-year-old participants (depression, r = 0.77, p < 0.001; anxiety, r = 0.66, p < 0.001; stress: r = 0.56, p < 0.05).

Conclusion

Young people (aged 12–24 years) who have a parent with cancer report a complex array of needs, many of which go unmet. The preliminary findings reported may be used to inform service providers in the development and evaluation of need-based programs to redress these unmet needs and thus ameliorate the effects of parental cancer. Services addressing information and school-based interventions are particularly pertinent given these current results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In Australia in 2005, there were more than 39,000 deaths from cancer and over 100,000 people who were newly diagnosed [1]. Such a diagnosis not only affects the individual but also has a flow-on effect to family members, friends and the wider community. Although in the last decade, there has been improvement in cancer survival rates, cancer continues to impact on family members as it shifts toward a chronic condition [2]. While it is difficult to establish the specific number of adolescents and young adults impacted by chronic parental illness, Worsham and Crawford [3] suggest that it is reasonable to assume that these numbers are substantial. Much previous literature has focused on younger children and the impact of diagnosis on their well-being. As such, the research agenda for adolescents and young adults is underdeveloped and important to address. The World Health Organisation defines youth as people between the ages of 15–24. Often, this definition is used in conjunction with adolescents (people aged 10–19 years) and young people, which describes the combined cohort of 10–24-year-old [4].

The psychosocial vulnerability of young people impacted by parental cancer has been acknowledged as being considerable [4], and this population exhibits high scores on stress, anxiety and depression measures [5, 6]. However, previous research has tended to focus on descriptions of the offspring’s functioning, such as disruptions to coping, psychological functioning and development, for example, a decline in school performance [7–10]. While these descriptions have been useful in gaining insight into the emotional and psychological difficulties that these young people experience, they have not directly identified the psychosocial needs of this population and thus have offered only limited guidance to service providers.

Relatively few studies have focused on the psychosocial needs of young people who have a parent with cancer. These studies have focused on the need for information (for example, about the seriousness of the illness) and support (for example, from friends) [11–14] and have not directly and systematically assessed whether or not these needs were being met. However, it is important to develop larger-scale research that investigates other potential classes of need associated with the offspring’s functioning [15] and the extent to which these self-expressed needs are being met by service providers. Such research is important for a number of reasons: It allows for a more detailed understanding of how young people who have a parent with cancer perceive, experience and express their needs [11], and it provides direct assessment of the type, number and magnitude of these needs and whether they have been met. An important application of such knowledge is in the planning of better psychosocial intervention programs for this group [11, 16], particularly as clinicians and service providers move from service-led toward need-led practice [17]. Finally, a need-based research can also lead to an understanding of the factors that contribute to resilience in these young people, which may help to prevent or reduce the likelihood of developing long-term mental health problems.

The primary aims of the current study were to identify the psychosocial needs of young people who have a parent with cancer, to assess whether these needs have been met and to present data on the face and content validity and reliability of a need-based measure specifically designed for offspring [the Offspring Cancer Needs Instrument (OCNI)].

Method

Design

Given that there has been little research conducted into the needs of young people who have a parent with cancer, a qualitative exploratory method of data collection was deemed the most appropriate in the first instance. Study 1 thus consisted of a focus group and telephone interviews with young people whose parent has cancer and a staff survey. In study 2, a quantitative survey was utilised to measure psychosocial needs and to ascertain whether these needs had been met.

Study 1: qualitative phase

Participants

Participants were recruited through the “Sydney and Central Division” of CanTeen Australia. CanTeen is the Australian organisation for young people living with cancer. CanTeen provides programs and services designed to address the psychosocial needs of young people (12–24 years old) living with cancer, and these include a mixture of psychological support and development and recreationally based activities. The organisation offers services to (1) patient members (young people who have, or have had, a cancer diagnosis), (2) offspring members [young people who have a parent with cancer or have had a parent who died from cancer (bereaved offspring members)], and (3) sibling members [young people who have a sibling with cancer or have had a sibling who died from cancer (bereaved sibling members)]. Letters of invitation were sent to offspring members. Hence, the age range 12–24 years was the focus of this research, as it represents the demographic serviced by the organisation. In total, there were 14 participants in the focus group/interview stage. As this represents 22% of those approached, 64 participants were invited in the first instance.

Focus group

Six young people participated in the focus group (age range, 12–17 years, M = 13.7 years. Four were female, and all participants were currently residing with their diagnosed parent.Footnote 1 Parents had been diagnosed with a range of cancers: Hodgkin’s (n = 2), bowel (n = 2) and ovarian (n = 2). All had completed treatment.

Telephone interviews

Eight participants, ranging in age from 13 to 22 years (n = 5, 12–17 years; n = 3, 18–24 years; M = 16.9 years), participated. Four were female, and seven currently lived at home with their diagnosed parent. Parents had been diagnosed with a range of cancers: leukaemia (n = 2), breast (n = 3) myeloma (n = 2), and kidney (n = 1). Most had completed treatment (n = 7).

Staff survey

Fifty-seven staff members from CanTeen were invited to participate in a web-based survey asking about their perceptions of the needs of young people who have a parent with cancer. Twenty-six (46%) staff members participated, of whom 20 were female and six were male. Of those who participated, 15 had worked for the organisation for <12 months and 11 for >12 months. Respondents held positions in management (n = 7), recreation/program (n = 11), administration (n = 3) and other areas (n = 5).

Materials

Focus group and telephone interviews

To ensure consistency across the two information collection media, a booklet was developed to be used in both environments by the interviewer. The booklet contained two sections: The first included a series of open- and closed-ended questions that asked participants to detail their perceptions of the needs/unmet needs they experienced as a result of their parent’s cancer, for example, “What did you feel you needed during this time in your life?” The second section involved a series of closed-ended questions that required participants to rate their endorsement from 0% to 100% (where 0 = no agreement and 100 = full agreement) for needs identified in the literature review.

Staff survey

The online survey contained open- and closed-ended questions designed to gather information regarding staff members’ perceptions of the needs of young people who had a parent diagnosed with cancer. For example, “Please list up to 5 important needs that you think young people aged 12–24 with a parent with cancer have.”

Procedure

The study was endorsed by both the University of Western Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee and the Ethics and Young People Sub-committee of CanTeen Australia. Careful consideration was given to the issues of anonymity, confidentiality and consent due to the age of the sample population and the sensitivity of the research area. For individuals aged 12–17 years, parental consent was gained before the young person was approached to participate. Potential participants were contacted via telephone and invited to take part in the focus group. If this was inconvenient, they were invited to participate in a one-on-one telephone interview at a time convenient to them. All participants were given a brief description of the research and were later presented with an information sheet and consent form. Those who gave verbal consent to participate in either the focus group or the telephone interview were then asked to consider their felt needs regarding their experience with their parent’s cancer. These needs were then discussed within the focus group/telephone interview.

The focus group was led by a facilitator with an observer present, while the telephone interview was conducted by a sole researcher. In both instances, each participant was invited to discuss their self-identified needs. Needs identified in the literature but not discussed by participants were named by the facilitator, and participants were asked to indicate the extent to which they endorsed each need.

The staff members’ survey was sent electronically with accompanying information outlining the purpose of the study. Consent was implicit in the return of completed surveys. A 3-week turnaround was set, with a reminder email sent to all staff 1 week before the closing date.

A literature review was also undertaken to identify need themes apparent in previous research. The search terms used included parental, cancer, children, young people, adolescent, needs and psychosocial. Searches were performed in the following databases: EBSCOHost, ScienceDirect, PubMed, Ovid and PsychInfo.

Data analysis

Given the project’s multiple data sets and the need to generate an integrated set of findings, triangulation was employed. Triangulation is a methodological approach that contributes to the validity of research results when multiple methods, sources, theories and/ or investigators are employed [18]. Data from each of the methods were content-analysed for emerging themes. Themes identified from two or more sources (for example, identified in the previous literature and raised by the focus group) were subjected to subsequent methodological triangulation. This process resulted in the identification of overriding ‘metathemes’ or domains of need for young people who have a parent with cancer.

Results

Eight need domains were identified and are outlined in Table 1.

Study 2: quantitative phase

Participants

Eligibility criteria included being aged 12–24 years of age and having a parent diagnosed with any type or stage of cancer within the past 5 years. Eligible young people were identified from the existing organisation database of CanTeen Australia (n = 463). Seventy-two potential participants were excluded for various reasons (incorrect address, parent had died and did not wish to be contacted). Eligible young people were sent a letter inviting them to participate in the study. Nineteen participants completed an online version and 97 participants completed a paper-and-pencil version (N = 116), yielding an overall response rate of 30%. This response rate is comparable with other recent Australian research with young people affected by cancer (patients and siblings) [19–21]. Other factors influencing the return rate may include the use of a postal survey with no telephone follow-up and opt in research design minus a direct invitation from someone known to the participant [22–24]. Furthermore, young people may be disengaged from the process due to the nature of their current circumstances—living with a parent with cancer. Due to the anonymous nature of the study, no details are available on non-respondents.

Sixty-six per cent of the sample were female, ranging in age from 12 to 24 years (M = 16 years), and 34% were male, ranging in age from 12 to 24 years (M = 15 years). Most were born in Australia (94%). Ninety per cent of respondents lived with their diagnosed parent, and a range of diagnoses were noted, the predominant cancers being breast (44%), non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (10%) and bowel (10%). Further sample characteristics and information relating to diagnosis and treatment variables are outlined in Table 2.

Materials

Socio-demographic and medical questions

These included age, gender, country of birth, time since parent’s diagnosis, cancer type and treatment types.

Needs instrument—the Offspring Cancer Needs Instrument

A pool of survey items was developed from the qualitative needs analysis outlined in study 1. Items generated were designed to map as many of the components of each domain as possible. This process was conducted by two researchers independently, who then discussed and agreed on the items. This process resulted in 67 items that were considered representative of the scope of needs identified. Items were worded to be appropriate for a reading age of approximately 11 years, as measured by the Flesch Reading Ease formula [25]. Participants were presented with a sentence stem: “In the last 12 months, I needed....” and then asked to rate the level of each item on a 4-point scale: 1 = no need, 2 = low need, 3 = moderate need, and 4 = high need. Those answering with some level of need were also asked, “Has this need been met?” to which they responded either yes or no. For example, items included the following: information—“To get information about my parent’s cancer in a way that I could understand”; peer support—“Support from my friends” and “To talk to someone my own age who has been through a similar experience with cancer; feelings—“Help dealing with feelings of frustration and anger related to my parent’s cancer”; respite and recreation—“To be able to have fun”; support for carers—“Assistance with the responsibility of looking after my parent with cancer”; education/work—“Help with concentrating on tasks at school, TAFE, university, or work”; family—“To feel able to openly communicate with my family about my parent’s cancer”; and access to support—“Help being linked in with an appropriate support service”. The stem “In the last 12 months I needed…” was chosen in an attempt to capture a broad range of needs across the cancer journey. In addition, an open-ended item allowed participants to list up to three additional needs and to rate how much of a need (low, moderate and high) it was for them. The OCNI was available as both a paper-and-pencil questionnaire and as an online survey. The two forms were identical in presentation and item ordering.

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) is a 25-item self report screening instrument for 7-17 year olds [26]. It covers five dimensions: conduct problems; emotional symptoms; hyperactivity; peer relationships; and prosocial behaviour. Participants were asked to report the extent to which each item applied to them over the past 6 months using a 3-point scale, where 0 = not true and 2 = certainly true. A total difficulties (SDQ-TD) score of 0–40 was generated by summing the scores from all of the scales except “prosocial behaviour”. The SDQ exhibits good internal consistency (mean α = 0.73) and retest stability after 4–6 months (M = 0.62; [26]). It also possesses good content, construct and criterion-related validity [27, 28].

Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scale—21

Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scale—21 (DASS21) is a 21-item (short version) self-report screening scale designed to measure depression, anxiety, and stress levels [29]. Participants are required to consider how much the item applied to them over the past week and rate their response on a 4-point severity/frequency scale, where 0 = did not apply to me at all, and 3 = applied to me most of the time. The scale has been shown to have high internal consistency, possess good construct validity [29, 30] and yield meaningful discriminations in a variety of settings [31]. Participants aged 18–24 years completed the DASS21.

Procedure

This second phase of the project also received ethical endorsement from the University of Western Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee and from the Ethics and Young People Sub-committee of CanTeen Australia. For individuals aged 12–17 years, parental consent was gained before the young person undertook the questionnaire. A research pack was then posted to participants, consisting of an information sheet (outlining confidentiality and anonymity conditions), information regarding the online version of the survey (including the site address and participant password) and a hard copy of the survey and a reply-paid envelope. The young person’s consent was implicit in the completion of the survey. Participants were given 6 weeks to complete the survey, with a reminder letter sent out at 4 weeks.

Data analysis

Face and content validity of the measure were assessed via subjective feedback and analysis of the survey item requesting participants to list any other additional needs. Reliability analyses were also conducted on each of the domains to examine the internal consistency of these areas. As per Kline’s [32] recommendation, a Cronbach’s alpha level of 0.70 was used as the cut-off score to indicate acceptable reliability. Preliminary construct validity was examined in relation to the hypothesised relationship between unmet needs and scores on measures of psychosocial functioning. Specifically, it was predicted that there would be a positive correlation between the number of unmet needs reported and scores on the SDQ-TD (for those aged 12–17 years) and the DASS-21 (for those aged 18–24 years). As per Hills’ [33] recommendation, a significant correlation of 0.30 and above was used as the cut-off coefficient to indicate acceptable validity.

Results

The self-expressed needs, and unmet needs, of young people who have a parent with cancer

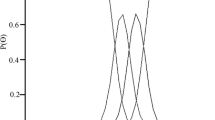

The majority of young people (97.4%) endorsed at least one need, 90% specified 10 or more needs and approximately 25% endorsed 50+ needs. On average, 36.2 needs were endorsed per person (SD = 17.44, range = 0–66). Furthermore, 87% of the sample indicated that at least one need was unmet, 43% had 10 or more unmet needs and just under a quarter had 20+ unmet needs. The distribution of the total number of needs endorsed and total number of unmet needs per person is outlined in Fig. 1. On average, participants reported 12.82 unmet needs (SD = 13.33, range = 0–54). Of those young people who reported 10 or more needs, approximately 47% indicated that their needs had been met. This may be an artefact of the sample (peer support organisation members) and could be taken to indicate that the services currently being offered by the organisation are meeting these needs. For example, it may well be that the healthy living psychoeducation program is addressing some of the practical issues faced by young people.

Young people identified both needs and unmet needs within each of the conceptual domains (see Table 3). The peer support domain (96%), respite and recreation (94%) and expressing and coping with feelings (92%) had the highest percentages of participant endorsement of one or more needs. In relation to needs that had not been met, nearly three quarters (73%) of the young people in this sample indicated one or more within the peer support domain, 57% had one or more in the education and work environment area and 56% reported one or more in the domain of expressing and coping with feelings.

The top 10 needs and the top 10 unmet needs endorsed by participants are outlined in Table 4. These provide insight into current unmet needs. In this sample, unmet needs concerning support from peers, access to information and dealing with feelings were the most represented domains.

Reports of initial reliability and validity

While it was outside the scope of the present research to conduct tests of construct validity (via factor analysis) and test–retest reliability for the needs measure, evidence of reliability and validity can be attested to. Internal consistency reliability for the eight domains was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha with all coefficients reaching an acceptable level (information α = 0.92; peer support α = 0.90; expressing and coping with feelings α = 0.90; respite and recreation, α = 0.81; carer support, α = 0.85; education/work environment, α = 0.80; family factors α = 0.72; access to support α = 0.64)

Face and content validity of the need items was assessed through the qualitative phase of the research by consulting previous literature in the area, young people directly and staff who work in the field. Subjective feedback indicated that the items were comprehensive and acceptable. Furthermore, all items included in the measure were utilised by at least some of the participants, indicating that the content of the measure was relevant for assessing the needs of young people who have a parent with cancer. Participants were also given the opportunity to indicate any additional needs that they may have that were not included in the questionnaire. In total, there were 14 additional needs stated by 12 participants. Of those 14 needs, only three (each only stated once) were considered by two raters not to have been represented in the survey. The small number of additional need items suggested by participants further confirms the content validity of the needs measure.

Although no current measure exists with which the needs measure (OCNI) can be directly compared, the hypothesised relationship between unmet needs and mental health was examined. It was expected that a higher number of unmet needs would correlate positively with psychological distress, and this expectation was borne out by the current results: For young people aged 12–17 years (n = 98), there was a significant positive correlation with mental health scores as measured by the SDQ-TD (r = 0.33, p < 0.001): for young people aged 18–24 years (n = 18), mental health was measured using the DASS-21, and a significant positive correlation was found between total number of unmet needs and depression scores (r = 0.77, p = 0.000), anxiety scores (r = 0.66, p = 0.002) and stress levels (r = 0.56, p = 0.010). Of note, approximately 50% of 12–17-year-old had scores in the at-risk/ clinically elevated ranges on the SDQ-TD, and nearly 45% of 18–24-year-old had scores which placed them in the at-risk/ clinically elevated ranges for anxiety (n = 6) and stress (n = 6), far exceeding the 15–20% reported in normative data.

Discussion

The main outcome of the study was the identification of a wide range of psychosocial needs facing young people who have a parent with cancer and an assessment of whether or not these needs had been met, extending the scope of previous need-based research [11–14]. The majority of young people surveyed expressed varied needs during this period of their lives, with over 90% indicating 10 or more needs and a quarter of the sample endorsing 50 or more needs. Psychosocial areas that were most salient included the domains of peer support, respite and recreation and expressing and coping with feelings. These results indicate that it is important to provide support and services to offspring in order to foster greater communication and interaction with peers, to alleviate the pressures of their parent’s diagnosis and treatments by providing time out and recreational activities so that the young person regains a sense of normalcy in their lives and to assist them to effectively express and cope with their emotional reactions.

Importantly, the study also revealed that these needs are often not met. Around 43% of participants indicated they had 10 or more unmet needs and just under a quarter reported 20 or more unmet needs. Most of these unmet needs related to the domains of peer support, a supportive education and work environment, expressing and coping with feelings and the desire for information. These findings are particularly pertinent in light of the pattern emerging from the unmet needs assessment and psychological distress scores: For both the 12–17- and 18–24-year brackets, there was a high positive correlation between number of unmet needs and adverse mental health scores and a higher than normal proportion of participants at risk of psychological problems. Hence, this finding should assist service providers in the area: for example, the current study reports on young people’s need for friends who understand what they are going through and for more lenient and understanding teachers. This would seem to indicate that an educational intervention that sought to inform both peers and teachers alike of the impact of parental cancer may help to ameliorate further distress at school for the young person. In line with previous findings [11], young people also voiced their need for information relating to all aspects of the cancer journey (diagnostic and prognostic issues); thus, age-appropriate information booklets and web based information could also assist. Such targeted interventions overall may assist in improving mental health outcomes.

The development of the psychosocial need-based measure—the OCNI—is the first step in the process of identifying and addressing the deleterious effects of parental cancer for young people. The OCNI has both face and content validity and shows strong internal reliability. As such, the major strength of this research lies in the direct assessment of the needs of young people who have a parent with cancer. Need-based research is becoming increasingly important as psychological interventions and programs become more need-based [17]. Initial measurement of unmet needs provides guidance to health professionals and service providers in developing prevention- and intervention-based programs and services that are more responsive young people.

This study was not without limitations. First, most of the participants were from a Western culture (Australia), and thus, results cannot be generalised to other cultures. Second, there were unequal numbers of participants in the 12–17 and 18–24-year-old categories and between the genders, which may have led to an under-representation of some needs and over-representation of others. Last, the participants were drawn from a peer support organisation for young people living with cancer. Thus, young people not involved with such an organisation, and non-respondents within the organisation, may have other needs not identified in the present study. The response rate of 30% also limits the generalisability of the findings. Furthermore, it is not known whether young people who initially join a peer support organisation have greater needs than those who do not join, that is, they are more distressed and hence seek out support, or it may be that members of such an organisation report fewer needs than the broader population of young people who have a parent with cancer due to the social support inherent within CanTeen. Additional investigation is therefore warranted using different sub-populations of young people who have a parent with cancer. Hence, an important next step in the development of the OCNI as a research and clinical tool is to further examine the construct validity and reliability of the instrument. Currently, a study is underway to further assess these properties, using a broader community sample.

Overall, the study takes an important step towards redressing the dearth of research regarding the identification of the psychosocial needs of young people who have a parent with cancer through direct need-based research. Assessment of whether or not these needs are currently being met by service providers will also assist in program and intervention development, with the view to promote health and well-being outcomes for young people who experience the protracted illness of a parent who has been diagnosed with cancer.

Notes

Diagnosed parent denotes the parent/guardian who has been diagnosed with cancer, regardless of treatment status.

References

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) AACR (Australasian Association of Cancer Registries) (2007) Cancer in Australia: an overview, 2006. Cancer series no. 37, cat no. CAN 32. AIHW, Canberra

Watson M, St James-Roberts I, Ashle S, Tilney C, Brougham L, Baldus C et al (2006) Factors associated with emotional and behavioural problems among school age children of breast cancer patients. Br J Cancer 94:43–50

Worsham NL, Crawford EK (2005) Parental illness and adolescent development. Prev Res 12:3–6

World Health Organisation. http://www.who.int. Cited 19 April 2010

Osborn T (2007) The psychosocial impact of parental cancer on children and adolescents: a systematic review. Psycho-Oncol 16:101–126

Heiney SP, Bryant LH, Walker S, Parrish RS, Provenzano FJ, Kelly KE (1997) Impact of parental anxiety on child emotional adjustment when a parent has cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 24:655–661

Adams-Greenly M, Beldoch N, Moynihan R (1986) Helping adolescents whose parents have cancer. Sem Oncol Nurs 2:133–138

Compas BE, Worsham NL, Ey S, Howell DC (1996) When mom or dad has cancer: II. Coping, cognitive appraisal, and psychological distress in children of cancer patients. Health Psychol 15:167–175

Vess JD, Moreland JR, Schwebel AI (1985) An empirical assessment of the effects of cancer on family role functioning. J Psychosoc Oncol 3:1–16

Visser A, Huizinga GA, van der Graaf WTA, Hoekstra HJ, Hoekstra-Weebers JEHM (2004) The impact of parental cancer on children and the family: a review of the literature. Cancer Treat Rev 30:683–694

Kristjanson LJ, Chalmers KI, Woodgate R (2004) Information and support needs of adolescent children of women with breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 31:111–119

Chalmers KI, Kristjanson LJ, Woodgate R, Taylor-Brown J, Nelson F, Ramserran S, Dudgeon D (2000) Perceptions of the role of the school in providing information and support to adolescent children of women with breast cancer. J Adv Nurs 31:1430–1438

Forrest G, Plumb C, Ziebland S, Stein A (2006) Breast cancer in the family—children’s perceptions of their mother’s cancer and its initial treatment: qualitative study. Br Med J 332:998–1003

Rees CE, Bath PA (2000) The psychometric properties of the Miller Behavioural Style Scale with adult daughters of women with early breast cancer: a literature review and empirical study. J Adv Nurs 32:366–374

Grabiek BR, Brender CM, Puskar KR (2006) The impact of parental cancer on the adolescent: an analysis of the literature. Psycho-Oncol 16:127–137

Houts PS, Yasko JM, Kahn B, Schelzel GW, Marconi KM (1986) Unmet psychological, social, and economical needs of persons with cancer in Pennsylvania. Cancer 58:2355–2361

Asadi-Lari M, Tamburini M, Gray D (2004) Patients’ needs, satisfaction, and health related quality of life: towards a comprehensive model. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2:1–15

Farmer JE, Marien WE, Clark MJ, Sherman A, Selva TJ (2004) Primary care supports for children with chronic health conditions: Identifying and predicting unmet family needs. J Pediatr Psychol 29:355–367

Patterson P, Millar B, Visser A (2010) The development of an instrument to assess the unmet needs of young people who have a sibling with cancer: piloting the Sibling Cancer Needs Instrument (SCNI). J of Pediatr Oncol Nurs (in press)

Millar B, Patterson P, Desille N (2010) Emerging adulthood and cancer: How unmet needs vary with time-since-treatment. Palliat Support Care 23:1–8. doi:10.1017/S1478951509990903

McLoone J, Wakefield CE, Lenthen K, Butow P, Cohn RJ (2009) Finishing cancer treatment: the positives and negatives for adolescents and their families. Asia-Pac J Clin Oncol 5(s2):A165

Nakash RA, Hutton JL, Jorstad-Stein EC, Gates S, Lamb SE (2006) Maximising response to postal questionnaires—a systematic review of randomised trials in health research. BMC Med Res Meth 6:5

Junghans C, Feder G, Hemingway H et al (2005) Recruiting patients to medical research: double blind randomised trial of “opt-in” versus “opt-out” strategies. BMJ 331:940

Coast J, Flynn TN, Salisbury C, Louviere J, Peters TJ (2006) Maximising responses to discrete choice experiments: a randomised trail. Appl Health Econ Health Pol 5:249–260

Flesch R (1948) A new readability yardstick. J Appl Psychol 32:221–233

Goodman R (1997) The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 38:581–586

Goodman R (2001) Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 40:1337–1345

Goodman R, Meltzer H, Bailey V (1998) The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a pilot study on the validity of the self-report version. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 7:125–130

Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF (1995) Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales, 2nd edn. Psychology Foundation, Sydney

Antony MM, Bieling PJ, Cox BJ, Enns MW, Swinson RP (1998) Psychometric properties of the 42-item and 21-item versions of the Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scales (DASS) in clinical groups and a community sample. Psychol Assess 10:176–181

Brown TA, Korotitsch W, Chorpita BF, Barlow DH (1997) Psychometric properties of the Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scales (DASS) in clinical samples. Behav Res Ther 35:79–89

Kline P (1999) The handbook of psychological testing, 2nd edn. Routledge, London

Hills AM (2008) Foolproof guide to statistics, 3rd edn. Pearson Education Australia, Frenchs Forest

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Phyllis Butow from the University of Sydney and Dr. Jim Beattie and Mr. Brett Millar, who are part of the CanTeen research team, for their comments and edit of the paper in readiness for submission. The authors also thank the participants for their willingness to share their experiences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Patterson, P., Pearce, A. & Slawitschka, E. The initial development of an instrument to assess the psychosocial needs and unmet needs of young people who have a parent with cancer: piloting the offspring cancer needs instrument (OCNI). Support Care Cancer 19, 1165–1174 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-010-0933-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-010-0933-7