Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study was to evaluate the utility of participating in two benchmarking exercises to assess the care delivered to patients in the dying phase using the Liverpool Care Pathway for the Dying Patient (LCP).

Design

The study uses questionnaire evaluation of the benchmarking process assessing the quality/usefulness of: sector feedback reports, individual feedback reports and the workshop element.

Setting

Healthcare professionals representing hospital, hospice and community settings.

Participants

Sixty-two out of 75 potential participants (83%) returned completed questionnaires.

Main outcome measure

A study-specific questionnaire was administered as part of the final workshop element of the benchmarking exercise. The questionnaire contained a mixture of ‘Likert’-type responses and open-ended questions.

Results

Participants from all sectors reported that the feedback reports contained the right amount and level of data (82–100%), that they were easy to understand (77–92%) and that they were useful to the organisation (94–100%). Respondents particularly valued the opportunity to discuss more fully the results of the benchmark and to network and share elements of good practice with other attendees in the workshops. Participants from the hospital sector identified changes in practice that had occurred as a result of participation.

Conclusions

Using comparative audit data that are readily available from the LCP and using workshops to discuss the findings and plan future care was perceived as a valuable way in which to explore the care delivered to dying patients in a variety of settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

This paper focuses on the perceived usefulness of benchmarking in care of the dying. Separate pilot benchmarking exercises were undertaken in two cancer networks in the northwest of England. Information from a sample of patients whose care in the last days and hours of life had been delivered and recorded using the LCP for the dying patient was analysed from a range of organisations to provide aggregate and comparative performance data. Individual reports were provided to each participating organisation, and representatives were invited to attend a workshop afternoon where the results were discussed, good practice shared and action planning for the future was undertaken. This paper assesses the views of those who attended the workshops regarding the usefulness of such benchmarking in care of the dying and identifies important lessons for the conduct of and feedback from the National Care of the Dying Audit–Hospitals that has recently been completed in England.

Introduction

The quality of care that is provided to patients in the final days and hours of their lives has enjoyed increased attention in both academia and popular culture in recent years (e.g. Ellershaw and Ward 2003, ‘How to have a good death’, BBC, March 2006). The Government’s End of Life Care Strategy (www.eoli.nhs.uk) was launched in 2004 to promote the delivery of timely and effective end of life care for patients regardless of diagnosis and place of care. A major element in this initiative was to ‘roll out’ three existing end of life care frameworks: the Liverpool Care Pathway for the dying patient (LCP www.mcpcil.org.uk); the Gold Standards Framework (GSF www.goldstandardsframework.nhs.uk) and the Preferred Place of Care document (www.cancerlancashire.org.uk/ppc.html). Operating within different timeframes and settings, each tool aims to skill up generalists to deliver quality care by streamlining the delivery of that care and promoting appropriate communication at the end of life.

The Liverpool Care Pathway for the Dying Patient framework

The LCP focuses specifically on care delivery in the last days and hours of life. It provides a comprehensive template of appropriate, evidence-based, multidisciplinary care for this discrete phase. Incorporating the physical, psychological, social, spiritual/religious and information needs of patients and carers, the pathway is organised into three sections: initial assessment, ongoing assessment, care after death. The LCP is designed to replace all other documentation at the end of life and is structured to facilitate audit and outcome measurement [1, 2].

More than 1,000 organisations in a variety of care settings in the UK and beyond are now actively engaged in implementing and using the LCP. A major challenge is to find ways to sustain the profile and use of the LCP to promote continuous quality improvement (CQI) within a given environment. CQI implies “improvement, change and learning” [3], and a vital component of CQI is the regular monitoring, evaluation and feedback of progress via the analysis of objective data [4].

Benchmarking

As researchers in the palliative care arena are aware, undertaking robust research is a challenge; this has been well documented in terms of poor recruitment rates, high attrition levels and difficulty in identifying suitable outcomes measures [5, 6]. Berwick [3], however, has highlighted an important distinction between measurement for judgement and measurement for improvement, suggesting that “When we try to improve a system...we need just enough information to take a next step in learning”. In this sense, benchmarking may represent an important methodology for encouraging improvement.

Ellis [7, 8] suggests that benchmarking can be extremely useful in supporting the development of best clinical practice because of its structure of assessment and reflection. In essence, benchmarking is a collaborative rather than a competitive enterprise that initially involves the sharing of relevant information on the delivery of care with other organisations. This information is then analysed to identify both gaps in performance and examples of best practice. The findings are shared, and elements of best practice are adopted with the aim of improving performance. Matykiewicz and Ashton [9] suggest that using a workshop as part of the benchmarking process facilitates awareness and provides a catalyst to change.

Benchmarking in two cancer networks in the north of England

A national audit of the delivery of care via the LCP in acute hospitals in England (NCDAH), which will result in the development of data-driven benchmarks, has recently been completed. As a precursor, pilot benchmark exercises were carried out in two cancer networks in the northwest of England.

Data from a consecutive sample of a maximum of 20 recently used LCPs were submitted and analysed from each of the 16 organisations in phase 1 (five hospitals, six hospices and five community teams) and 24 participating organisations in phase 2 (12 hospitals, 6 Hospices and 6 Community teams). Contextual service-related data were also collected from each organisation. A wealth of information regarding the nature of care delivered in different sectors and comparisons of the performance of individual organisations with the aggregate performance of their relevant sector resulted. This was based on a total of 315 patients (96 hospital, 119 hospice and 100 community) in phase 1 and 394 patients (207 hospital, 100 hospice and 87 community) in phase 2.

In both phases, each organisation received a summary of their individual performance on each goal of the LCP compared to the performance of their relevant sector as a whole. A summary presentation was also compiled that illustrated the performance of each of the sectors across the cancer network on each of the goals. The feedback was designed to give a relatively simple graphical illustration of performance and contained stacked bar charts illustrating the proportion ‘achieved’ (i.e. goal met), ‘varianced’ (i.e. goal not met) and ‘missing’ (i.e. nothing coded against the goal) for each goal on the pathway (Fig. 1). In addition, relevant information regarding organisational contextual factors (i.e. size, number of deaths, number of deaths on an LCP) and patient demographics (i.e. median patient age, diagnosis and median number of hours on the LCP) was also included. Figure 2 illustrates some examples of the type of feedback received by participants.

Two months after receiving their feedback, up to three representatives from each of the participating organisations, including the person responsible for collecting the data, were invited to attend a workshop afternoon. The participants were made up predominantly of nursing and medical staff, some with managerial responsibility. The first part of the workshop involved presentation of the overall cancer network summary results. The second brought participants together within their relevant sectors to review their own performance and to discuss and share elements of good practice. They were also encouraged to develop an action plan for their individual organisation in the light of their results and these discussions.

Aim

The aim of the present study was to evaluate workshop participants’ perspectives regarding participation in the pilot benchmark exercises. Specifically, the views of participants regarding the feedback received and the workshop element of the undertaking was sought using a study-specific questionnaire. The data were analysed within sector (hospital, hospice, community) to identify any differences/similarities in perspectives.

Method

Local Research Ethics Committee approval was sought for the work, and it was granted for the questionnaire evaluation element of phase 1 but deemed unnecessary for phase 2, as it was then felt to represent service evaluation rather than research per se.

The questionnaire evaluation of the benchmark process was undertaken as part of the workshop afternoon. Questionnaires are suited to gathering reliable subjective information such as user satisfaction. They are also generally quick to administer and can be analysed relatively easily. The questionnaire was devised to gauge participants’ perspectives of the benchmark exercise regarding the quality and relevance of the feedback and involvement in the workshops. The questionnaire contained a mixture of ‘Likert’-type responses and open-ended questions to allow participants to comment more fully where appropriate. It was initially piloted for face validity with health professional colleagues who suggested improvements to aid understanding and to avoid ambiguity.

In phase 1, potential participants were provided with information leaflets and were asked to give written informed consent before participation. Individuals were informed of their right not to participate or to withdraw their data at any time without detriment or the need for explanation. In phase 2, the same information was given verbally at the outset of the project and again at the workshop, and agreement for participation was assumed by the return of questionnaires.

Sample

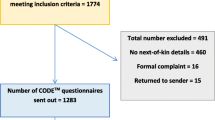

Three representatives from each participating organisation were invited to attend the workshop element of the project in both phases (maximum attendance at the two workshops = 120). A total of 75 participants attended the two workshops and were invited to complete a questionnaire about their experiences (n = 40 phase 1 and n = 35 phase 2).

Results

Sixty-two completed questionnaires were submitted for analysis at the end of the workshops, representing a response rate of 83%. Twenty-five participants came from the hospital sector, 20 from the hospice and 17 from the community. A majority of respondents were from the nursing profession in both phases (Table 1).

Most questions involved Likert style responses which are summarised in the following tables. Any qualitative comments made by respondents have been included alongside the quantitative summary to which they pertain.

Overall perceptions

Respondents were overwhelming in their agreement that participation in the benchmark exercise had been useful to the organisation (95% hospital, 95% hospice and 94% community). Almost three quarters of respondents from the hospital sector (72%) thought that participation in the exercise had already altered care in their organisations, providing the following examples:

“Improved symptom management, communication with relatives also improved” (W2)

Heightened awareness about diagnosing dying and needs of dying amongst multi-professional teams. (W2)

Is beginning to improve communication across sectors. (W1)

Around one third in the hospice and community sectors (35 and 29%, respectively) agreed.

Between 83 and 100% of respondents from each of the sectors felt that the exercise should be repeated at least every 2 years.

Sector feedback

Feedback was provided to each participating organisation on the aggregate performance on each of the goals on the LCP for hospital, hospice and community. Participants were asked to comment on the amount of information provided, ease of understanding and how useful they had found it. They were also given the opportunity to offer further qualitative comments.

The vast majority of respondents from each sector reported that the feedback presentation contained the right amount of information (96% hospital, 100% hospice and 88% community) and that it was either ‘useful’ or ‘very useful’ to their organisation (100% hospital, 100% hospice and 94% community). Whilst the majority again reported that the feedback reports were easy to understand (80% hospital, 90% hospice and 77% community) and comments were generally positive “...Yes, easy to understand, not heavy going at all” (W1), a small minority in each of the sectors were either ambivalent towards the clarity of the report (20% hospital, 5% hospice and 11.5% community) or disagreed that it was easy to understand (11.5% community). It would appear that the “[the large] amount of information...” (W2) or the “complexity of the data rather than poor illustration” (W1) had been particularly challenging.

Respondents also gave comments regarding how to improve the presentation of the data, such as providing a written summary after each section, and the provision of data ranges on each bar chart to further facilitate understanding, i.e.to “see where you compare at sector level” (W2).

Individual organisation feedback

Separate feedback was also provided to each participating organisation on their own performance compared to that of the appropriate aggregate sector performance on each of the goals on the LCP. Again, participants were asked to comment on the amount of information provided, ease of understanding and how useful they had found it. They were also given the opportunity to offer further comments.

The vast majority of respondents again agreed that the reports contained the right amount of information (96% hospital, 95% hospice and 82% community) and that it was either useful or very useful to their organisation (96% hospital, 95% hospice and 94% community). Similarly, 92% of respondents from the hospital environment, 90% from the hospice and 88% from the community also agreed that the reports were easy to understand.

In the main, written comments centred around areas for education and the ease of dissemination to other staff, which provided a way in which to examine their own organisations to “learn” and “inform practice” (W2). Several respondents suggested that taking part and receiving the feedback had provided a new view on the delivery of care that would help to clarify future action:

eye opening! Gave strong ideas [about] where we need to go from “here!”. (W1)and that

It was useful to start the thought process. (W2)

Workshops

Participants were asked for their views on the value of the workshop afternoon. Specifically, they were asked to rate their level of agreement with a series of statements regarding networking, sharing good practice, gaining a better understanding of the results and creating an action plan for the future. Again, they were invited to supplement their answers with appropriate comments. Table 2 summarises the responses to the Likert style questions:

Respondents from each sector either agreed or agreed strongly that the workshop afternoon provided valuable opportunities to network with colleagues, share elements of good practice, gain a better understanding of the meaning of the data and put together an action plan for improvement in their organisation. A majority of respondents from all sectors reported that the presentation of the sector results given at the start of the workshop afternoon was beneficial, and helped to clarify the information and provide contextual information around the project:

made much clearer to understand following an explanation by the research fellow who undertook the...exercise. (W1)

Comments were generally positive and indicated that the workshop had helped participants to reflect on the project and to get a feel for what the data meant. One commented that they felt

more focused on what [we are] trying to achieve. (W2) and another that the workshop provided a

...good arena to share practices...and discuss problems that appear to be common.... (W1)

In addition, the workshops facilitated a focus on those areas where future educational resources should be directed:

now I know what needs to be done in my trust and can take it forward (ie education). (W1)

Identified areas requiring further education/re-enforcement. (W2)

Discussion

The results clearly illustrate that all elements of the project were overwhelmingly positively viewed by the vast majority of respondents from each sector. The feedback presentations of the data (individual and sector) were designed to provide easily accessible graphical summaries of comparative performance. However, they did contain large amounts of information, and it was important to establish how easy they were to interpret, and therefore, how useful the feedback was to participants.

Whilst respondents in all sectors indicated that feedback had been informative, useful and, in the main, relatively easy to understand, the results do highlight some room for improvement. The fact that respondents reported that the explanation given at the workshop was a useful aid to understanding suggests that explanatory notes in addition to the graphs would have been a useful addition to the report. This finding has influenced the design of reports for the feedback of results in the National Care of the Dying Audit–Hospitals.

The results confirm that receiving further explanation and having the opportunity to reflect on the data as a group in the workshops enhanced understanding and provided a useful opportunity to share experiences with and learn from others striving for similar goals. Northcott [10] suggests that the discourse that takes place around the data in workshops can enable ‘NHS actors’ to find meaning and context in and to more fully connect and engage with the evaluation process. Being given the opportunity to reflect on a process allows deeper insight into the usefulness of the outcome of that process [3] and sharing information is integral to continually improving the quality of care [8]. Thus, the workshop element was clearly invaluable in providing a mechanism for ‘closing the audit loop’ and in emphasising those areas where future education should be focused.

It is interesting to note that whilst almost three quarters of respondents in the hospital sector felt that participation in the benchmark had had a direct impact on the delivery of care, only around a third in the other two sectors felt the same. This finding may have been influenced by the timing of completion of the questionnaire (i.e. only between 4 and 6 weeks of receiving the feedback) or it may reflect true differences that exist between the sectors. Previous research, for example, has illustrated that whilst the LCP is a useful teaching and audit tool in the hospice environment, its direct impact on the standard of care delivery is perceived to be less important than in the hospital sector [11]. Several respondents, however, did identify specific improvements in levels of communication between health professionals and relatives, within multidisciplinary teams and across sectors that had already occurred as a result of participation in the benchmarking exercise. In addition, the fact that respondents from all sectors felt that the exercise should be repeated further reinforces the perceived usefulness of formal, data driven reflection and the opportunity to share one’s triumphs and challenges with like-minded others.

Limitations

Whilst the 85% response rate for completion of questionnaires suggests that a representative sample of those attending the workshops was gained, the numbers in each sector were still relatively small and the findings should be interpreted carefully. Formal recording of the action plans created as part of the workshops and re-auditing to evaluate improvements in the environment would further strengthen this work.

Conclusions and implications for practice

The benchmark exercise was well received and evaluated by staff in a range of organisations across the three sectors. There was much interest in repeating the exercise and, as such, this approach appears to offer a robust process for the monitoring and evaluation of key elements of care that has the potential to promote continuous quality improvement for patients in the last days of life. Using data to formally reflect on the standard of care given can also help to keep the document ‘alive’ in the environment and to inform and strengthen the education programme that is vital to support and sustain the use of the pathway.

Some practical lessons were also learned in terms of how best to feedback a wealth of data so that participants can clearly identify areas of relative success and areas where future education should be focused. In this way, it has the potential to ensure that scarce resources are used in the most efficient way.

References

Ellershaw J, Smith C, Overill S, Walker SE, Aldridge J (2001) Care of the dying: setting standards for symptom control in the last 48 hours of life. J Pain Symptom Manage 21(1):12–17

Ellershaw J and Wilkinson S (eds) (2003) Care of the dying—a pathway to excellence. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Berwick DM (1996) A primer on leading the improvement of systems. BMJ 312:619–622

Graham NO (1995) Quality in health care: theory, application, and evolution. Aspen Publications, New York

Rinck GC, van den Bos GA, Kleijnen J, de Haes HJ, Schade E, Veenhof CH (1997) Methodologic issues in effectiveness research on palliative cancer care: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol 15(4):1697–1707

Westcombe AM, Gambles MA, Wilkinson SM, Barnes K, Fellows D, Maher EJ, Young T, Love SB, Lucy RA, Cubbin S, Ramirez AJ (2003) Learning the hard way! Setting up an RCT of aromatherapy massage for patients with advanced cancer. Palliat Med 17(4):300–307

Ellis J (1995) Using benchmarking to improve practice. Nurs Stand 9(35):25–28

Ellis J (2000) Sharing the evidence: clinical practice benchmarking to improve continuously the quality of care. J Adv Nurs l32(1):215–225

Matykiewicz L, Ashton D (2005) Essence of Care benchmarking: putting it into practice. Benchmarking: An International Journal 12(15):467–481

Northcott D (2005) Benchmarking in UK health: a gap between policy and practice? Benchmarking: An International Journal 12(17):419–435

Gambles M, Stirzaker S, Jack B, Ellershaw J (2006) The Liverpool Care Pathway in hospices: an exploratory study of doctor and nurse perceptions. Int J Palliat Nurs 12(9):414–421

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ellershaw, J., Gambles, M. & McGlinchey, T. Benchmarking: a useful tool for informing and improving care of the dying?. Support Care Cancer 16, 813–819 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-007-0353-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-007-0353-5