Abstract

Purpose

This study examined symptoms reported by patients after open-ended questioning vs those systematically assessed using a 48-question survey.

Materials and methods

Consecutive patients referred to the palliative medicine program at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation were screened. Open-ended questions were asked initially followed by a 48-item investigator-developed symptom checklist. Each symptom was rated for severity as mild, moderate, or severe. Symptom distress was also evaluated. Data were collected using standardized pre-printed forms.

Results

Two hundred and sixty-five patients were examined and 200 were eligible for assessment. Of those assessed, the median age was 65 years (range 17–90), and median ECOG performance status was 2 (range 1–4). A total of 2,397 symptoms were identified, 322 volunteered and 2,075 by systematic assessment. The median number of volunteered symptoms was one (range zero to six). Eighty-three percent of volunteered symptoms were moderate or severe and 17% mild. Ninety-one percent were distressing. Fatigue was the most common symptom identified by systematic assessment but pain was volunteered most often. The median number of symptoms found using systematic assessment was ten (0–25). Fifty-two percent were rated moderate or severe and 48% mild. Fifty-three percent were distressing. In total, 69% of 522 severe symptoms and 79% of 1,393 distressing symptoms were not volunteered. Certain symptoms were more likely to be volunteered; this was unaffected by age, gender, or race.

Conclusion

The median number of symptoms found using systematic assessment was tenfold higher (p<0.001) than those volunteered. Specific detailed symptom inquiry is essential for optimal palliation in advanced disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

An estimated 555,500 Americans died from cancer in 2002 [1]. Relieving distressing symptoms and managing complications are essential in improving the quality of life of patients with advanced cancer [2]. Advanced cancer patients are polysymptomatic with a median of 11 (range 1–27) symptoms [3–5]. The most common symptoms are fatigue, dry mouth, pain, and anorexia. The prevalence of certain symptoms is influenced by age (e.g., pain), gender (e.g., nausea), and the primary site (e.g., cough and lung cancer). Some symptoms are associated with shorter survival. In clinical practice, a significant difference appears to exist between symptoms reported following an open-ended question and those identified when specifically inquired. We report a study that examined this phenomenon and compared symptoms volunteered vs those systematically assessed on a 48-question survey.

Materials and methods

We conducted a prospective study to compare the number of symptoms volunteered during interview vs those chosen on a 48-item survey (systematic assessment). The 48-item survey was an empirically derived investigator-developed checklist of symptoms experienced by patients with advanced cancer. It was based on the classic internationally used system review used during standard clinical history taking and physical examination [6]. Similar approaches have been used by our group in the past yielding valuable information about the symptomology of advanced disease [3–5]. The current checklist was modified slightly from prior versions based on our collective experience in using such lists in both clinical practice and research activities. The study was approved by the Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Board. All inpatients and outpatients referred to the Palliative Medicine Program at the Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Center during a 5-month period were enrolled. No specific referral criteria are used for admission to the program; that decision is at the discretion of the referring physicians. Delirious, sedated, and comatose patients and those with hearing or speaking problems were excluded. Demographic data, e.g., age, gender, race, primary disease, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, were collected at initial consultation by the palliative medicine attending or fellow physician. All of the interviews were conducted by physician research fellows who were specifically trained for the task and who were aware the data was collected solely for research purposes. Standardized pre-printed forms were used. The interview took about 10 min to complete.

Interview questions

The interview started with an open-ended question: “How are you feeling?” followed by a second symptom-directed question, “What symptoms are you having now?” The patient was asked to rate every volunteered symptom for severity (mild, moderate, or severe) and also for distress by asking, “Is it bothering or distressing you?” A third chance to report symptoms was given before starting the systematic assessment by asking, “Is there anything else?”

Systematic assessment

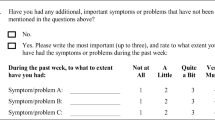

The systematic assessment consisted of a 48-symptom survey completed by directly asking the patient about specific symptoms. Symptoms volunteered initially were excluded. The assessment included another symptom category to capture symptoms not identified in the survey. The patient was asked to rate every reported symptom for severity (mild, moderate, or severe) and for distress (yes/no) by asking, “Is it distressing or bothering you?” A copy of the evaluation tool is in Fig. 1. The Bedside Confusion Scale (BCS) [7], which utilizes an observation of alertness at the time of patient interaction followed by a timed task of attention, was administered to all eligible patients (0—not confused, 1—borderline, and >2—confused) to determine cognitive function and its possible effect on symptom reporting.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were summarized as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and as the median and range for continuous variables. Percentages were rounded to the nearest whole number. The t test was used to compare the number of volunteered and systematically assessed symptoms between men and women, Caucasian and non-Caucasian, and those with Bedside Confusion Scale (BCS)<2 and BCS>2. The chi-square test was used to compare distress according to severity. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to determine correlates of symptom volunteering. The analysis model was developed using 2,397 symptoms, 322 of which were volunteered. Forty-four variables were considered in the model: patient type (inpatient or outpatient), gender, age, race, performance status, diagnosis type (cancer or non-cancer), whether the symptom was distressing (yes/no), symptom severity (mild, moderate, or severe), and absence or presence of 36 symptoms. Twelve symptoms could not be evaluated with logistic regression analysis because either all or none of these 12 symptoms had been volunteered. A stepwise selection procedure was used which allowed variables to enter the model if p<0.10 but required p<0.05 to remain in the final model. Results are summarized as the odds ratio (OR), 95% confidence interval for the odds ratio (OR), and the corresponding p-value. To quantify how these variables (symptom severity, distress, or specific symptoms) influenced the likelihood of volunteering, model-based probabilities of volunteering were done for all combinations of variables in the final multivariable logistic regression model.

Results

Patients

Two hundred and sixty-five consecutive patients were enrolled and screened. Sixty-five were not assessed; of these, >50% were delirious or sedated and 69% had an ECOG of 4. Two hundred were entered in the study (Table 1); 107 (54%) were men and 93 (46%) women. Median age was 65 years (range 17–90). One hundred fifty-four (77%) were Caucasian, 40 African American (20%), and six Hispanic or Asian (3%). One hundred twelve (56%) were outpatients and 88 (44%) inpatients. ECOG performance status was 1–82 (41%), 2–43 (21%), 3–60 (30%), and 4–15 (8%). Amongst the 181 cancer patients, metastases had been observed in 49 of them in the lymph node (27%), 45 in the lung (25%), 45 in the liver (25%), 36 in the bone (20%), 14 in the brain (8%), and 23 in other metastatic sites (13%). One hundred forty-seven (73%) scored less than 2 on the BCS, i.e., either were not confused as judged by the BCS or had a borderline score.

Number of symptoms

The total number of symptoms identified was 2,397, 322 (14%) were volunteered and 2,075 (86%) were generated by systematic assessment. The median number of volunteered symptoms was one (range zero to six) whereas the median on systematic assessment was ten (range 0–25) (p<0.001). Every symptom of the 48-symptom list was a complaint of at least one patient. The number of volunteered or systematically assessed symptoms between men and women did not differ significantly. The median number of volunteered symptom was one for both men and women (p=0.61) and the median number of systematically assessed symptoms was nine for men and ten for women (p=0.91). Although Caucasians reported more symptoms over-all [median 11 (range 0–29)] than non-Caucasians [median 9 (range 1–29)], the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.1). There was no difference in volunteered symptoms between those with BCS<2 and BCS>2.

Symptom severity and distress

Fifty-five (17%) of the 322 volunteered symptoms were mild, 104 (32%) moderate, and 163 (51%) severe; 292 (91%) were distressing (Fig. 2). One thousand (48%) of the 2,075 systematically assessed symptoms were mild, 716 (35%) moderate, and 359 (17%) severe; 1,101 (53%) were distressing. Fifty-five (6%) of the 1,055 mild symptoms were volunteered, 104 (13%) of the 820 moderate, and 163 (31%) of the 522 severe (Fig. 2). Two hundred ninety-two (21%) of the 1,393 distressing symptoms were volunteered (Fig. 3). Comparing distress according to severity, in all cases, the percentage of distressing symptoms increased as the severity increased.

The ten most common symptoms

In descending order, fatigue, dry mouth, pain, anorexia, weight loss, early satiety, insomnia, dyspnea, drowsiness, and constipation were the ten most common symptoms identified overall (Table 2). Pain was the most frequently volunteered symptom, followed by fatigue, anorexia, dizziness, vomiting, headache, dyspnea, nausea, cough, and bad dreams. In contrast, the most common assessed symptoms were dry mouth, weight loss, fatigue, early satiety, anorexia, insomnia, drowsiness, dyspnea, constipation, and depression (see Table 2). Less than 10% of patients volunteered early satiety, drowsiness, dry mouth, insomnia, and weight loss.

Evaluating the ten most common moderate or severe symptoms, pain was volunteered in 83% (when moderate or severe) but fatigue in only 49% and dyspnea in 27%. Volunteering moderate or severe early satiety, drowsiness, dry mouth, insomnia, and weight loss was also less than 10%. Amongst the ten most distressing symptoms, pain was volunteered in 85% when it was distressing but fatigue only in 42% and anorexia in 31%. Volunteering of distressing early satiety, dry mouth, insomnia, and weight loss was less than 10%.

Correlates of symptom volunteering

Pain was 70.3 times more likely to be volunteered than any other symptom. Distressing symptoms were 3.8 times more likely to be volunteered (Table 3) than those that were not. Severe symptoms were 4.3 and moderate 1.7 times more likely to be volunteered than mild symptoms. Specific symptoms most likely to be volunteered included pain, fatigue, headache, dizziness, nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, cough, dyspnea, anorexia, and constipation (Table 3). Model-based probabilities of volunteering symptoms (Table 4) indicated that severe distressing pain was 92% likely to be volunteered whereas the probability of mild non-distressing pain being reported was only 40%.

Discussion

An important principle in medical history taking is to ask open-ended questions to “allow patients to tell their own story.” However, in palliative care where the aim is to control the pain and other symptoms as much as possible to provide patients and their families the best quality of life, this may fail to detect aspects of the patients' symptomatology. A discrepancy may also exist between patient and family perception and physician assessment of certain symptoms [8–10] leading to inadequate treatment.

The patient population in our consultation service is seriously ill with advanced disease and a complex mixture of medical and psychosocial problems. All patients enrolled in the study had failed attempts at curative treatment in the past or wished not to receive any anti-tumor therapy and were checked mainly for management of symptoms and complications. The median age of the study population and the distribution of primary cancer sites were representative of the current causes of mortality from cancer in the USA. The study sample were all consecutive patients referred for palliative care. It is possible but unlikely that they are self-selected and therefore differ in important behavioral or cognitive characteristics. There is no other study we are aware of that has examined this issue of discrepant reporting. The overall symptom profile of this study population is typical of advanced cancer as described by several investigations [11–16].

We developed our scale based on our clinical experience in evaluating and managing patients with advanced disease. Nevertheless, our survey tool has not been exposed to psychometric evaluation. The available validated instruments do not cover all the symptoms patients with advanced cancer experience [11–16]. Another universal flaw (and one that may be uncorrectable) is that their practicality and reliability deteriorate in advanced disease [17–20] when assessment of symptoms is most important. A recent study [21] compared five symptom assessment tools already validated in palliative care (the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale, the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale, the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire, the Palliative Care Outcome Scale, and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer-Quality of Life-Core 30) to the symptoms noted in patient records. None of the five covered all symptoms listed in the medical records. The same study concluded that using such instruments to assess symptoms in palliative care represents a compromise between the wish for quick, practical, simple questions and our recognition that such supposedly simple methods will never give an in-depth understanding of the individual patient's unique situation. Our data supports this observation. Every symptom of our empirical 48-symptom list was a complaint of at least one patient in this study. This shows the need for a comprehensive symptom list and argues against a reductionist approach to this issue. For example, we have shown that the presence of dysphagia or early satiety was nearly equal in importance to performance status in independently predicting survival in advanced disease [22]. Validated scales often ignore common, and we believe important, symptoms such as early satiety [22].

In our study, a difference between the number of symptoms volunteered and identified on systematic assessment was expected, but not to the degree (tenfold) found. Severity and distress influenced voluntary reporting of symptoms. Symptoms were more likely reported if they were moderate to severe, or distressing. However, most of the symptoms identified only after systematic assessment were also moderate and severe in intensity and distressing. In fact, the majority of distressing (79%) or severe (69%) symptoms were not volunteered. The low level of volunteering important gastrointestinal symptoms such as weight loss places patients at significant nutritional risk.

It is difficult to know whether rating distress severity would have added any information to our primary objective of comparing the number of symptoms volunteered during interview vs those chosen on a 48-item survey. Rating amount of distress would have added a minimum of 48 more questions—burdensome to this patient population. Quantifying or ranking distress might be useful in a future study to compare volunteered symptoms vs non-volunteered distressing symptoms and assess if incremental degree of distress influences volunteering a distressing symptom.

The close relationship between symptom severity and distress perhaps challenges the concept that an assessment of distress separate from that of severity is essential [11]. Nevertheless, in our study, a large percentage of volunteered symptoms rated as mild and a fourth of systematically assessed mild symptoms were also reported as distressing. Symptom severity and distress therefore appear to be two distinct variables and, thus, should be evaluated separately. Persistence or chronicity of a symptom may be a greater predictor of distress (or likelihood of spontaneous report) than severity.

Although numeric scales might have enhanced assessment of some symptoms such as pain and fatigue, we chose a categorical rating scale for symptom severity for several reasons [21]. First, there is no evidence that numeric scales are superior to categorical scales in assessing symptoms such as diarrhea or heartburn. Second, from our experience with patients with advanced disease, we have found categorical scales that describe symptom severity easier to use and more understandable by the patient. Third, numeric or visual analogue scales often rate symptoms based on the worst previous experience of the symptom (even if the individual may never have experienced the symptom before). How much distress is needed for someone to volunteer a distressing symptom is an important question for future research.

It has been reported that variation in symptom prevalence is common and determined by the tool used to evaluate symptoms. One review of 49 studies of depression in cancer showed a prevalence range between 1 and 53% [22]. That may explain why some symptoms such as dry mouth were more prevalent in our study than reported previously. However, our current data are consistent with our prior reports. We have previously reported similar prevalence rates for most symptoms also identified in this study [23, 24]. We considered re-asking a patient with advanced disease about a symptom already volunteered repetitive, confusing, and burdensome. Our primary objective was to compare the number of symptoms volunteered during informal interview vs those chosen on a 48-item formal survey (not to compare subjective vs systematic assessment of symptom severity nor evaluate prevalence or other characteristics).

Sixty-five patients who were considered for this study were ineligible; about 25% of the total. They were excluded based on a global clinical judgment that their physical and/or neuro-psychological status prevented the completion of the study questionnaire. The BSC was completed subsequent to study entry and was not an entry criteria. The majority were cognitively impaired and/or had a poor performance status due to advanced disease. Although they were unable to participate in this study, the frequency with which this occurred raises the importance of the related issue of symptom assessment in persons with cognitive or communication impairment.

Although fatigue was the most common symptom and reported frequently as moderate or severe and distressing, it was less likely to be volunteered than pain. A possible explanation involves the mistaken perception that it is an inevitable component of advanced disease and treatment is unavailable or ineffective. The prevalence of other moderate/severe and distressing but poorly volunteered (<10%) symptoms, e.g., early satiety, drowsiness, dry mouth, insomnia, and weight loss, suggests the need for their specific inquiry and appropriate management.

Cancer patients may have concerns about reporting pain [25]. Some consider it is an inescapable consequence of cancer [26] while others believe that a good patient should refrain from complaining about it [27]. In early disease, patients may hesitate to talk about pain for fear that physicians may get distracted from curing the cancer [27, 28]. In advanced disease, such as in our study population, pain is perhaps more readily reported when present. However, physical and psychosocial barriers can still interfere with adequate treatment [29, 30]. Nevertheless, increased efforts in recent years to educate patients and professionals about pain may explain the high proportion of pain sufferers who volunteered the symptom.

Patients readily reported some symptoms more than others. Certain symptoms may have greater cultural significance. Some may be prioritized for report based on bias from previous or current medical interactions. Moreover, they may be unaware that treatment of certain symptoms, e.g. anorexia, dry mouth, or early satiety, is possible. Physicians should be careful in history taking as they may unknowingly direct what patients volunteer by preferentially asking about specific symptoms leading to further inquiry about related problems, but ignoring important non-voluntary information. Time pressures may also affect reporting. Patient education must also play a role. The greater likelihood of reporting pain perhaps reflects greater emphasis on cancer pain in recent years. Standard pain assessment tools exist but there are few formal means of communicating the complexity of other symptoms. For research purposes, reductionist approaches which focus on selected symptoms are insufficient in our view unless they are the sole object of inquiry. In routine clinical practice, our data suggests that at minimum we must adopt a detailed comprehensive systematic approach to symptom identification. All patients should at a minimum have a detailed symptom assessment at initial consultation and periodically thereafter. Symptom assessment using a combination of volunteered and systematic data collection may be optimal. In our opinion, amongst the validated measures, the best (judged by their comprehensiveness) are the modified Rotterdam Symptom Checklist [31] and the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale [32]. Legitimate debate will continue about whether assessment of patient symptoms or quality of life should be driven by physicians or patient perspectives [33]. Leveraging modern communication technology perhaps combined with patient self-assessment seems an appropriate response to the complex, time-consuming and important task of symptom detection and assessment. It appears that assessment of both severity and distress are important in this process.

Conclusions

There is a major discrepancy between the symptoms that persons with advanced disease experience and what they spontaneously report to their physicians. Symptoms such as early satiety, drowsiness, dry mouth, insomnia, and weight loss were common but often not volunteered. Specific symptoms most likely to be volunteered included pain, fatigue, headache, dizziness, nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, cough, dyspnea, anorexia, and constipation. Gender and ethnic background did not seem to influence symptom volunteering. Most non-volunteered symptoms were moderate or severe and also distressing. Symptom distress and severity were therefore not the only factors determining volunteering of symptoms. Several validated symptom and quality of life assessment tools are available but none covers all the symptoms patients with advanced disease may experience. Systematic symptom assessment that addresses physiological as well as psychological symptoms like the one we used in our study should ideally be used each time a patient is seen. Assessing symptom severity as well as distress is important as they appear to be reflecting different aspects of the symptom experience. Further studies are needed to assess if symptom chronicity or persistence, degree of distress, patient education, or other factors influence symptom volunteering. In the highly symptomatic cancer population, regular symptom assessment seems desirable and should not be confined to pain control or palliative medicine clinics. The optimal frequency and rigor of this process should be the object of future research.

References

Jemal A, Thomas A, Murray T, Thun M (2002) Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 52:181–182

Ingham JM, Portenoy RK (1996) Symptom assessment. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 10(1):21–39

Donnelly S, Walsh D, Rybicki L (1995) The symptoms of advanced cancer: identification of clinical and research priorities by assessment of prevalence and severity. J Palliat Care 11(1):27–32

Donnelly S, Walsh D (1995) The symptoms of advanced cancer. Semin Oncol 22(2 Suppl 3):67–72

Walsh D, Donnelly S, Rybicki L (2000) The symptoms of advanced cancer: relationship to age gender and performance status in 1,000 patients. Supportive Care Cancer 8:175–179

Simel DL (2004) Approach to the patient: history and physical examination. In: Goldman L, Ausiello D (eds) Cecil textbook of medicine, 22nd edn. WB Saunders, Phildelphia, PA, pp 18–23

Stillman MJ, Rybicki LA (2000) The bedside confusion scale: development of a portable bedside test for confusion and its application to the palliative medicine population. J Palliat Med 3(4):449–456

Sprangers MA, Aaronson NK (1992) The role of health care providers and significant others in evaluating the quality of life of patients with chronic disease: a review. J Clin Epidemiol 45(7):743–760

Stromgren AS, Groenvold M, Pedersen L, Olsen AK, Spile M, Sjogren P (2001) Does the medical record cover the symptoms experienced by cancer patients receiving palliative care? A comparison of the record and patient self-rating. J Pain Symptom Manage 21(3):189–196

Stromgren AS, Groenvold M, Sorensen A, Andersen L (2001) Symptom recognition in advanced cancer. A comparison of nursing records against patient self-rating. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 45(9):1080–1085

Portenoy RK, Thaler HT, Kornblith AB, Lepore JM, Friedlander-Klar H, Kiyasu E et al (1994) The Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale: an instrument for the evaluation of symptom prevalence, characteristics and distress. Eur J Cancer 30A(9):1326–1336

Zobora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Jacobsen P, Curbow B, Piantadosi S, Hooker C et al (2001) A new psychosocial screening instrument for use with cancer patients. Psychosomatics 42(31):241–246

Heedman PA, Strang P (2001). Symptom assessment in advanced palliative home care for cancer patients using the ESAS: clinical aspects. Anticancer Res 21(6A):4077–4082

Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, Selmser P, Macmillan K (1991) The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care 7:6–9

Cleeland CS, Mendoza TR, Wang XS, Chou C, Harle MT, Morrissey M et al (2000) Assessing symptom distress in cancer patients: the M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory. Cancer 89(7):1634–1646

de Haes JC, van Knippenberg FC, Neijt JP (1990) Measuring psychological and physical distress in cancer patients: structure and application of the Rotterdam Symptom Checklist. Br J Cancer 62:1034–1038

Caraceni A, Cherny N, Fainsinger R, Kaasa S, Poulain P, Radbruch L et al (2002) Pain measurement tools and methods in clinical research in palliative care: recommendations of an expert working group of the European Association of Palliative Care. J Pain Symptom Manage 23(3):239–255

Lloyd-Williams M (2001) Screening for depression in palliative care patients: a review. Eur J Cancer 10(1):31–35

Kaasa S, Loge JH, Knobel H, Jordhoy MS, Brenne E (1999) Fatigue. Measures and relation to pain. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 43(9):939–947

Lloyd-Williams M, Freidman T, Rudd N (2001) An analysis of the validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale as a screening tool in patients with advanced metastatic cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 22:990–996

Stromgren AS, Groenvold M, Pedersen L, Olsen AK, Sjogren P (2002) Symptomatology of cancer patients in palliative care: content validation of self-assessment questionnaires against medical records. Eur J Cancer 38(6):788–794

Massie MJ, Popkin MK (1998) Depression. In: Holland J, Rowland J (eds) Handbook of psychooncology. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 518–540

Walsh D, Rybicki L, Nelson KA, Donnelly S (2002) Symptoms and prognosis in advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer 10:385–388

Homsi J, Walsh D, Nelson KA, LeGrand SB, Davis M, Khawam E, Nouneh C (2002) The impact of a palliative medicine consultation service in medical oncology. Support Care Cancer 10(4):337–342

Ward SE, Goldberg N, Miller-McCauley V, Mueller C, Nolan A, Pawlik-Plank D et al (1993) Patient-related barriers to management of cancer pain. Pain 52(3):319–324

Levin DN, Cleeland CS, Dar R (1985) Public attitudes toward cancer pain. Cancer 56(9):2337–2339

Cleeland CS (1987) Barriers to the management of cancer pain. Oncology (Huntingt) 1(2 Suppl):19–26

Diekmann JM, Engber D, Wassem R (1989) Cancer pain control: one state's experience. Oncol Nurs Forum 16(2):219–223

Mann E, Redwood S (2000) Improving pain management: breaking down the invisible barrier. Br J Nurs 9(19):2067–2072

Miaskowski C, Dodd MJ, West C, Paul SM, Tripathy D, Koo P et al (2001) Lack of adherence with the analgesic regimen: a significant barrier to effective cancer pain management. J Clin Oncol 19(23):4275–4279

de Haes JCJM, van Knippenberg FCE, Neijt JP (1990) Measuring psychosocial and physical distress in cancer patients: structure and application of the Rotterdam Symptom Checklist. Br J Cancer 62(6):1034–1038

Portenoy RK, Thaler HT, Kornblith AB, McCarthy Lepore J, Friedlander-Klar H, Kiyasu E, Sobel K, Coyle N, Kemeny N, Norton L, Scher H (1994) The Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale: an instrument for the evaluation of symptom prevalence, characteristics and distress. Eur J Cancer 30A(9):1326–1336

Slevin ML, Plant H, Lynch D, Drinkwater K, Gregory WM (1988) Who should measure quality of life, the doctor or the patient? Br J Cancer 57:109–112

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The Harry R. Horvitz Center for Palliative Medicine is a World Health Organization demonstration project in palliative medicine

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Homsi, J., Walsh, D., Rivera, N. et al. Symptom evaluation in palliative medicine: patient report vs systematic assessment. Support Care Cancer 14, 444–453 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-005-0009-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-005-0009-2