Abstract

The initial treatment of childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is not standardized. Although corticosteroids are the first-line therapy for SLE, long-term, high-dose steroid therapy is associated with various side effects in children. The Japanese Study Group for Renal Disease in Children (JSRDC) has carried out a multi-center, randomized, controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of corticosteroid and mizoribine (MZB) therapy as an initial treatment for newly diagnosed juvenile SLE. Twenty-eight patients were treated with a combination steroid and MZB (4–5 mg/kg/day) (group S+M) drug therapeutic regimen, while 29 patients were treated with steroid only (group S); both groups were followed up for 1 year. The time to the first flare from treatment initiation was not significantly different between the two groups (Kaplan–Meier method, p = 0.09). During the period when the steroid was given daily (day 0–183), the time to the first flare from treatment initiation was significantly longer in the patients of group S+M than in those of group S (log-rank test, p = 0.02). At the end of the study period, there were no differences in the severity of proteinuria and renal function impairment between the two groups. No patients dropped out of the trial due to adverse events. In conclusion, our combined steroid and MZB drug therapeutic regimen was not shown to be significantly better than the steroid-only therapy as initial treatment for juvenile SLE. Whether MZB administered in a higher dose would be therapeutically advantageous can only be answered by further studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) tends to have a more severe and longer clinical course than adult-onset SLE [1, 2]. The chosen treatment should control disease activity and include measures to minimize adverse reactions to therapeutic agents, such as corticosteroids and immunosuppressants.

Immunosuppressants have been combined with corticosteroids in the treatment of SLE or lupus nephritis to improve the therapeutic effect of the drug regimen and to reduce the adverse events associated with steroid therapy [3–10]. The efficacy of cyclophosphamide [3, 4], rituximab [8], and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) [9, 10] for treating SLE or lupus nephritis has recently been demonstrated, although there are as yet no prospective controlled studies in children. The use of these drugs as first-line therapy for all juvenile-onset SLE patients is controversial because there are concerns regarding their safety [11].

Mizoribine (MZB), an immunosuppressive drug, is less myelosuppressive and less hepatotoxic than other immunosuppressants. Absorbed MZB phosphorylates into its active form mizoribine 5′-monophosphate, which selectively inhibits inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase and guanosine monophosphate synthetase [12]. Recent studies have shown that MZB is safe and effective for treating SLE [13], lupus nephritis [14], nephrotic syndrome [15, 16], and other pediatric diseases [17–20].

The Japanese Study Group for Renal Disease in Children (JSRDC) conducted a multi-center, randomized, controlled trial to investigate the efficacy and safety of mizoribine–corticosteroid combination therapy as the initial treatment for pediatric primary-onset SLE.

Methods

The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki principles. This trial was registered as a public trial in the database of the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN).

Patients had to fulfill the following inclusion criteria to be enrolled in the study: (1) newly diagnosed SLE based on the guidelines defined by the Children's Collagen Disease Study Group of the Health and Welfare Ministry (hypocomplementemia was added to the American Rheumatoid Association criteria); (2) aged 2 to 18 years; (3) written informed consent could be obtained from the patient and/or the patient's legal guardians. The exclusion criteria were: (1) diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis, diffuse scleroderma, polymyositis, or dermatomyositis; (2) history of immunosuppressive drug therapy; (3) history of steroid therapy of longer than 4 weeks before registration; (4) physician assessment of patient unsuitability for this trial. Patients who met the selection criteria were enrolled in this study from 1995 to 2004. After informed consent was obtained, the patients were randomly allocated into either the steroid plus MZB group (group S+M) or the steroid alone group (group S). The patients were then followed for 1 year.

The MZB treatment consisted of 4–5 mg/kg/day (maximum 250 mg) given orally twice daily to the patients in group S+M. The MZB dose was halved for patients whose creatinine clearance (Ccr) levels were less than 40 ml/min/1.73 m2.

The method of steroid usage was the same in both groups. Each patient initially received two courses of methylprednisolone pulse therapy (MPT) (30 mg/kg; maximum1 g daily for 3 days). Oral prednisolone (PSL), 40 mg/m2/day (maximum 40 mg/day), was given for the first 4 weeks, following which the dose was tapered to 20 mg/m2/day (maximum 20 mg/day) by decreasing the dose by 5 mg every 2 weeks. Thereafter, the oral PSL dosage was reduced by 2.5 mg every 4 weeks to a level of 10 mg daily. Maintenance steroid therapy consisted of 20 mg/m2/day on alternate days, followed by 10 mg/m2/day on alternate days.

A flare was defined as the presence of one or more of the following: (1) recrudescence of clinical manifestations; (2) a decrease in the serum C3 level to 50 mg/dL; (3) an increase in the anti-DNA antibody level to 50 IU/mL. Remission was defined as either an improvement of clinical manifestations or both an increase in the serum C3 level to 50 mg/dL and a decrease in the anti-DNA antibody level to 50 IU/mL. These definitions were determined by the Protocol Committee of the Study Group.

Steroid therapy for a flare consisted of one course of MPT, a subsequent 4-week course of oral PSL at 40 mg/m2/day, followed by reducing the PSL dosage by 10 mg every 2 weeks to a level of 20 mg/m2/day. Thereafter, the treatment protocol was the same as the initial induction therapy.

The primary endpoint was survival without a flare based on the time from treatment initiation to the first flare. Clinical experience has shown that the 1-year survival without flare can be assumed to be around 40% and, in the S+M group, it was expected to be around 60%. Therefore, assuming a 1-year survival without flare for group S+M of 60%, a sample size of more than 26 would be needed to have the lower 95% confidence limit for a survival rate of 30% with 90% power. For group S, the 95% confidence interval of survival would be 23–59% (assuming the point estimate for group S is 40%) by having a sample size of 30. For assessing safety, adverse events with a 5% incidence can be detected with 30 subjects. Considering that pediatric SLE is a rare disease, the recruitment of 50–60 subjects was considered to be feasible within a 9-year entry period.

Analyses of the primary endpoint were performed according to the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle. The survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared with the log-rank test.

The time from the remission to the first flare was also examined as one of the secondary endpoints. The flare rate (number of occurrences of first flare/person-years) was estimated for both groups and compared using the permutation test. Person-years were calculated as the sum of individual follow-up times until the occurrence of the first flare or the end of follow-up. The flare rate hazard ratio was analyzed using Poisson regression. The treatment effect controlling for type of renal morphology (type IV or not), proteinuria at baseline (+ or −), and gender (female or male) was used for the Poisson regression analysis. In these analyses, patients who had not experienced an event by the end of their follow-up were treated as censored observations.

Assessments of renal function, proteinuria, and required steroid dose were also conducted. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was evaluated using the Schwartz equation. Laboratory data were examined at the start and end of the trial and compared using Student’s t test. The two-sided significance level for the primary endpoint was set at 5%. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS for Windows, release 8.2 or higher (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) at the Medical Tokei Co. (Tokyo, Japan).

Results

From 1995 to 2004, 58 patients were randomly assigned to either group S (n = 30) or group S+M (n = 28). No data were available for one patient in group S. Based on the ITT principle, the analysis data set consisted of 57 patients. (Fig. 1) The mean follow-up period was 323.4 days for the patients in group S+M and 300.2 days for those in group S.

In group S+M, 5 patients discontinued the allocated regimen. In group S, 9 patients were dropped out because they were lost to follow-up or because of a protocol treatment violation. Immunosuppressive agents were used for flares in three cases and for the development of resistance to protocol treatment in one case.

The analysis data set consisted of 28 patients in group S+M and 29 patients in group S. Renal biopsies were performed at the time that SLE was diagnosed in 50 patients. At enrollment, there were no differences between the two groups with respect to patient age, gender, renal function, degree of proteinuria, or histological type of nephritis (Table 1).

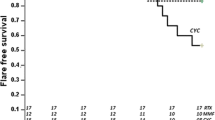

The result for the primary endpoint, survival without flare (the time from the treatment initiation to the first flare), is shown in Fig. 2 (p = 0.09). During the time that steroid was given daily [day 0–183 (24th week)] survival without flare was significantly different between the two groups (p = 0.02).

The time from the remission to the first flare was also not significantly different during the 1-year follow-up period (p = 0.10, data not shown). In addition, the mean time to remission from the treatment initiation was not significantly different between the two groups: 49.3 days in group S+M (n = 28) versus 46.6 days in group S (n = 27) (t test, p = 0.62).

The incidence of flare using the time to first flare was 0.507/year in group S+M and 0.893/year in group S; the hazard ratio was 0.568 (permutation test, p = 0.085). Twenty-nine patients had no flare, and 28 had flares during the follow-up period (11 patients in group S+M and 17 patients in group S). Poisson regression analysis revealed that the estimated hazard ratio was 0.568 (95% confidence interval 0.30–1.07, p = 0.080) for the simple analysis.

The total dose of corticosteroids [MPT (PSL equivalent) + oral PSL] was determined in 49 patients who were followed for at least 6 months. No significant difference (p = 0.65) was found in the total corticosteroid dose between group S+M (1292.4 mg/BSAm2/month) and group S (1335.9 mg/BSAm2/month).

Of the S+M patients, only three developed a flare while on daily steroids (mean steroid dose at the time of the flare 10.8 mg/day). Ten patients in group S developed a flare while on daily steroids (mean steroid dose 17.0 mg/day).

Table 2 shows that average renal function and proteinuria generally improved in both groups. The degree of improvement was not different between group S+M and group S.

Adverse events in both groups are shown in Table 3. None of the adverse events interfered with the continuation of study treatment in both groups.

Discussion

A greater number of patients from group S than from group S+M withdrew from the treatment regimen prior to completion of the 1-year study. As withdrawals due to flare or the patient being refractory to therapy were only seen in group S, these withdrawals may have been the result of the lack of MZB use.

The time to the first flare from treatment initiation and the time to the first flare from remission were both assessed. In terms of the effect of concomitant MZB treatment, the differences between the groups were not statistically significant at the 1-year follow-up. However, survival without flare from treatment initiation was significantly longer in patients of the S+M group than in those of the group S during the daily steroid treatment period. This result suggests the possibility that MZB at 4–5 mg/kg (maximum 250 mg) may be effective when given along with daily steroid treatment. Because long-term daily steroid maintenance treatment may be associated with potential adverse effects, it may be more appropriate to further increase the dose of MZB without increasing the dose of combined steroid treatment. The flare rate of patients in group S was comparable to that reported in previous studies with patients on a steroid-only regimen [13, 21].

The larger number of dropouts in group S may account for the absence of a statistically significant difference in the number of flares between the groups. There was also no difference between the groups in terms of the steroid dose, and this too seems to be attributable in part to the greater incidence of early dropouts in group S, which had a greater frequency of relapses.

No difference in the severity of proteinuria or renal dysfunction at the end of the study was observed between the treatment groups.

The evaluation of the safety of the therapeutic agents used according to the present protocol did not identify any particular points of concern. No noticeable adverse reactions were encountered with MZB; with the exception of a single case of mild hyperuricemia, MZB was demonstrated to be safe. One group S patient developed a hypertensive convulsion during the course of MPT; nevertheless, once the patient's blood pressure was controlled, the trial treatment could be continued. All other adverse events that occurred during the period the patients were receiving steroid therapy were mild, and none interfered with the continuation of the study treatment. There was no difference between group S+M and group S with respect to the incidence or severity of adverse events.

Conclusion

A randomized, controlled trial was conducted involving a substantial number of children with SLE to assess the safety and efficacy of the initial treatment regimens. The corticosteroid and MZB combination therapy assessed in our study was not associated with any safety concerns, but it did not appear to have any statically significant benefit in terms of suppressing flares. Whether MZB in a higher dose is of therapeutical advantage can only be determined by further studies.

References

Klein-Gitelman M, Reiff A, Silverman ED (2002) Systemic lupus erythematosus in childhood. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 28:561–577

Stichweh D, Arce E, Pascual V (2004) Update on pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Opin Rheumatol 16:577–587

Ausin HA, Balow JE (2000) Treatment of lupus nephritis. Semin Nephrol 20:265–276

Bounpas DT, Austin HA III, Vaughn EM, Klippel JH, Steinberg AD, Yarboro CH, Balow JE (1992) Controlled trial of pulse cyclophosphamide in severe lupus nephritis. Lancet 340:741–745

Bansal VK, Beto JA (1997) Treatment of Lupus Nephritis: A meta-analysis of clinical trial. Am J Kidney Dis 29:193–199

Flanc RS, Roberts MA, Strippoli GF, Chadban SJ, Kerr PG, Atkins RC (2004) Treatment for lupus nephritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1):CD002922

Carneiro JR, Sato EI (1999) Double blind, randomized, placebo controlled clinical trial of methotrexate in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 26:1275–1279

Nwobi O, Abitbol CL, Chandear J, Seeherunvong W, Zilleruelo G (2008) Rituximab therapy for juvenile-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Pediatr Nephrol 23:413–419

Bijl M, Horst G, Bootsma H, Limbug PC, Kallenberg CG (2003) Mycophenolate mofetil prevents a clinical relapse in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus at risk. Ann Rheum Dis 62:534–539

Chan TM, Li FK, Tang CS, Wong RW, Fang GX, Ji YL, Lau CS, Wong AK, Tong MK, Chan KW, Lai KN (2000) Efficacy of Mycophenolate Mofetil in patients with diffuse proliferative lupus nephritis. N Engl J Med 343:1156–1162

Katsifis GE, Tzioufas AG (2004) Ovarian failure in systemic lupus erythematosus patients treated with pulsed intravenous cyclophosphamide. Lupus 13:673–678

Yokota S (2002) Mizoribine: mode of action and effects in clinical use. Pediatr Int 44:196–198

Aihara Y, Miyamae T, Ito S, Kobayashi S, Imagawa T, Mori M, Ibe M, Mitsuda T, Yokota S (2002) Mizoribin as an effective combined maintenance therapy with prednisolone in child-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Pediatr Int 44:199–204

Tanaka H, Tsugawa K, Suzuki K, Nakahata T, Ito E (2006) Long-term mizoribin intermittent pulse therapy for young patients with flare of lupus nephritis. Pediatr Nephrol 21:962–966

Honda M (2002) Nephrotic syndrome and mizoribine in children. Pediatr Int 44:210–216

Goto M, Ikeda M, Hataya H, Ishikura K, Hamasaki Y, Honda M (2006) Beneficial and adverse effects of high-dosage Mizoribin therapy in the management of children with frequently relapsing nephrotic syndrome. Nihon Jinzo Gakkaishi 48:365–370

Nagaoka R, Kaneko K, Ohtomo Y, Yamashiro Y (2002) Mizoribine treatment for childhood IgA nephropathy. Pediatr Int 44:217–223

Yoshioka K, Ohashi Y, Sakai T, Ito H, Yoshikawa N, Nakamura H, Tanizawa T, Wada H, Maki S (2000) A multicenter trial of mizoribine compared with placebo in children with frequently relapsing nephritic syndrome. Kidney Int 58:317–324

Tsuzuki K (2002) Role of mizoribine in renal transplantation. Pediatr Int 44:224–231

Takei S (2002) Mizoribine in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Pediatr Int 44:205–209

Hiramoto R, Honda M (1997) Initial treatment of 54 pediatric patients with systemic lupus erythematosis. In: The 32nd Annual Meeting Japanese Society for Pediatric Nephrology, Tokyo

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients and physicians who participated in this trial: H. Tochimaru (Hokkaido), M. Awazu (Tokyo), T. Ogata (Tokyo), J. Miyamoto (Tokyo), K. Ishikura (Tokyo), N. Yata (Tokyo), T. Shijyaku (Kanagawa), A. Saito (Kanagawa), R. Hiramoto (Chiba), C. Nakahara (Ibaragi), K.Tamura (Ibaragi), Y. Kamiyama (Tochighi), T. Miura (Tochigi), Y. Kobayashi (Tochigi), A. Yoshino (Saitama), K. Obata (Saitama), S. Amemiya (Yamanashi), K. Higashida (Yamanashi), K. Iijima (Hyougo), H. Miyamoto (Hyougo), K. Shimomiya (Hyougo), H.Nozu (Hyougo), K.Ohta (Hyougo), Y. Ito (Fukuoka), K. Hatae (Fukuoka), C. Sato (Saga) and A. Furuse (Kumamoto).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

An erratum to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00467-009-1411-7

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tanaka, Y., Yoshikawa, N., Hattori, S. et al. Combination therapy with steroids and mizoribine in juvenile SLE: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Nephrol 25, 877–882 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-009-1341-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-009-1341-4