Abstract

Background

Currently, no generally accepted curriculum for operating room nurses (OR nurses) working with robotic-assisted surgery (RAS) exists. OR nurses working with RAS require different competencies than regular OR nurses, e.g. knowledge of the robotic system and equipment and specific emergency undocking procedures. The objective of this study was to identify learning goals for a curriculum for OR nurses working with RAS and to investigate which learning methods should be used.

Methods

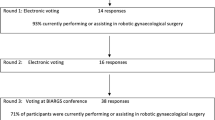

A three-round Delphi approach, with an additional survey, was used in this study. Four OR nurses from every department in gynecology, urology, and surgical gastroenterology doing RAS in Denmark were invited to participate.

Results

The response rates were 93%, 81%, and 79%, respectively, in the three rounds of the Delphi survey and 68% in the additional survey. After the processing of data, a list of 57 learning goals, sorted under 11 domains, was produced. 41 learning goals were rated Relevant, Very relevant, or Essential spread over 10 of the 11 domains. The top 3 learning goals rated as Essential: Identify the most common injuries related to patient positioning during robotic-assisted surgery and know how to avoid them, Connect, calibrate and handle the scope, Perform an emergency undocking procedure. The panel rated Supervised training during surgery on patients as the most relevant learning method, followed by Dry lab and Team training.

Conclusions

The learning goals identified in this study, can be used as the basis for a curriculum for OR nurses working with RAS. During the processing, it became clear that there is a need to further investigate issues such as communication challenges, awareness of emergency procedures, and differences in the skills required depending on the role of the RAS nurse.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The use of robotic-assisted surgery (RAS) is rapidly growing and in the last two years, the number of worldwide procedures has increased by 28% [1]. The robotic surgical team typically consists of a primary surgeon (console surgeon), one patient-side surgical assistant (doctor or Registered Nurse First Assistant (RNFA)), and two operating room nurses (OR nurses) respectively a scrub nurse and a circulating nurse. To prevent user error and recognize potential patient harms, well-trained staff members are as important as the equipment and instruments when doing RAS [2]. Because of the technical aspects of RAS, the team is highly dependent on the competencies of the OR nurses before, during, and after the procedure [3,4,5]. An example could be emergency situations that are more complex during robotic surgery. With the operating robot connected to the patient, there is a risk of delay in the team´s access to the patient during an emergency, and familiarity with the robotic system is essential to be able to act swiftly [2, 6, 7].

Besides the robotic system and equipment, RAS differs from traditional open or laparoscopic surgery in that the surgeon works from a console and is not near the patient and the rest of the surgical team, which can make the team´s communication more difficult [8,9,10].

As safe RAS is depending on the technical- and non-technical skills of the surgical team, there is a need to know how to train the surgical team in the best ways possible. While surgeons often train for RAS in dedicated training facilities, most OR nurses undergo training for RAS in a master-apprenticeship setup during actual RAS procedures [3, 5]. This training method for nurses may impact the course of the procedure and patient safety, and literature shows that OR nurses are calling for education in a more formal setting [3].

Several curricula for RAS have been developed [11, 12] but solely with the focus on how to train doctors to become console surgeons and bedside assistants. Established and recognized curricula in settings such as the European Association of Robotic Urology Section (ERUS) Robotic Curriculum [13] and Fundamentals of Robotic Surgery [14] also focus exclusively on the above-mentioned training of doctors. As mentioned above OR nurses need training in a more formal setting for becoming RAS OR nurses, but no educational curricula have been published. Furthermore, there is a lack of training in non-technical skills (NTS) in existing robotic training curricula and this can pose a risk to patient safety [15]. In accordance with “Kerns six-step approach” for curriculum development [16] it is important to identify relevant learning objectives when developing curricula, but also to identify for whom it is important and how the learning objectives are best taught.

The objectives of this study were to identify relevant content for a curriculum for OR nurses working with RAS, the most useful learning methods for each learning goal, and for whom they were relevant.

Material and methods

We used the Delphi method which is a systematic approach to gather information and reach a consensus between a group of participants (Delphi Panel), with experience in the topic that is being investigated [17]. Through three rounds, the participants were asked their opinion on the topic, presented with the anonymous answers of the entire panel, and asked to re-evaluate and/or rate the items of the topic. All participants and their answers were kept anonymous, to reduce the influence of dominant individuals [17,18,19]. We added an extra survey where participants were asked to choose the relevant learning methods for each learning goal and for whom the learning goals were relevant depending on their role during surgery.

Delphi panel

All departments in Urology, Gynecology, and General Surgery doing RAS in Denmark (15 different departments covering all five regions of Denmark) were invited to participate with four nurses from each department. All participants were experienced RAS OR nurses.

Processing group

A processing group was formed for this study. The purpose of this group was to process the data gathered from the Delphi Panel. The processing group was composed of experienced RAS OR nurses and two surgeons with a background in medical education. Altogether the group covered the above-mentioned specialties as well as all regions in Denmark.

Questionnaire design and distribution

The questionnaires for the Delphi Study were distributed using the online software SurveyXact (Rambøll Management Consulting, Aarhus, Denmark). Distribution letters were written in Danish while the questionnaires were written in English. The Delphi Panel had the opportunity to answer in English or Danish. The processing group then translated any Danish answers into English, during the processing meetings.

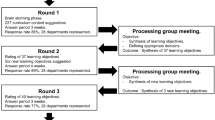

The Delphi process

The Delphi Panel was given four weeks to answer the questionnaire in each round, except for the third round, which collided with two different national holidays and therefore the participants were granted an extra week for this round. Each week a reminder e-mail was sent to the participants, who had not yet replied.

Round 1

In the first round, an e-mail was sent to each member of the Delphi Panel informing them about the aim of the study, the Delphi process itself, the intended use of the results, and a time schedule. In the questionnaire, the Delphi Panel were asked about their experience as a registered nurse (RN), OR nurse, RAS nurse, respectively. Furthermore, we asked them to state which team role they usually had (circulating nurse, scrub nurse, RNFA). Finally, the panel was asked an open-ended question: “Which learning goals do you find relevant to include in a curriculum for OR nurses for robotic-assisted surgery?”. The panel could suggest as many learning goals as they wanted. The questionnaire for round 1, can be found in the supplementary material. At the end of the first round, the learning goals suggested by the Delphi panel were filed in an Excel document, in random order for anonymization purpose, and afterwards sent to the processing group, in preparation for the first processing group meeting. At the process group meeting, duplicates were removed, clarification issues were discussed and resolved, and a list of learning goals, sorted in domains defined by the processing group, was produced. During this process any learning goals suggested in danish, were translated into English.

Round 2

In the second round, the Delphi panel was presented with the list of learning goals. The participants were asked to determine the relevance of each learning goal. This was done using a five-point scale (1 = not relevant, 2 = less relevant, 3 = relevant, 4 = very relevant, 5 = essential). The panel also had the opportunity to comment on the learning goals and/or suggest new learning goals to the list. The ratings and the newly suggested learning goals were sent to the processing group after the completion of the round. At the process group meeting, the new learning goals were indexed in the domains, duplicates were removed, and any clarification issues were discussed and resolved.

Round 3

In the third round, the panel was presented with the rating results from the previous round and then asked to make one final rating of the learning goals, once again using the above-mentioned five-point scale. In this round, the panel could not comment or suggest new learning goals.

Additional survey

An additional survey was sent to the panel immediately after the third Delphi round. In this survey, we asked the panel in which role (circulating nurse, scrub nurse, or RNFA) each learning goal was relevant. We also asked the panel to state which learning method they found relevant for each learning goal. (Table 1) The panel could select more than one role or learning method per learning goal.

Data analysis

The data from the ratings of learning goals were processed using a combination of the measures; Interquartile range (IQR), median, and percentage of the panel agreeing on 4 or 5 on the five-point scale. This is to define the learning objectives in relation to the scale Essential, Very relevant, Relevant or Not relevant (Table 2). This method has been used previously in similar consensus studies and with these pre-defined criteria and the inclusion of the interquartile range cutoffs to the consensus criteria, a high relevance score is only given when there is a low spread among answers. [20, 21]. The data were analyzed using SPSS V.24. (IBM Inc., Armonk, New York, USA).

Results

The 15 departments in Denmark that perform RAS were invited to participate with four OR nurses each, a total of 60 participants. However, two departments were only able to participate with two and three OR nurses, respectively, and one member of the Delphi panel withdrew from the study during the first round. The remaining 56 OR nurses had a median experience of 21 years as a Registered Nurse (range 2–40), 15 years as OR nurse (range 2–36), and 6 years as RAS nurse (range 1–12). All OR nurses in the Delphi panel worked as a scrub nurse daily, 92% as a circulating nurse daily, and 15% as a RNFA daily.

The response rates of the Delphi rounds were 93%, 81%, 79%, respectively, and 68% in the additional survey. In the first round, 327 learning goals were submitted by the Delphi panel. After processing and removal of duplicates, a list of 55 learnings goals, sorted under 11 domains was produced. In the second round, the Delphi panel submitted 29 comments and 2 suggestions for additional learning goals, which were added, and two learnings goals were rephrased for clarification.

In the third round, the Delphi panel rated 32 out of the 57 learning goals as Essential while 16 were rated as Not relevant. These, not relevant, learning goals were spread over 6 of the 11 domains. For 52 learning goals, the panel was very much in agreement during the rating of the learning goals, with an IQR of 0 or 1. Two learning goals, Be able to safely change robotic instruments during procedure and Be able to describe the functions and responsibilities of different team members, rated as Relevant and Very relevant, split the panel with an IQR of 2.

The 57 learning goals were sorted under 11 domains. Nine domains covered practical aspects of RAS nurse responsibilities, before, during, and after a robotic-assisted procedure. Another domain: Non-technical skills, covered basic non-technical skills but related to robotic-assisted surgery and yet another: Necessary competencies before working with robotic-assisted surgery, covered basic OR nurse competencies, not specifically related to robotic-assisted surgery. The domains are displayed in Table 3.

The additional survey on learning methods showed that the panel agreed on Supervised training during surgery on patients as being the most relevant method to obtain the learning goals. This method was mentioned as the most important for all but seven of the learning goals and was in the top three of relevant learning methods in all but one. For the three learning goals under the domain of Emergency procedures, the preferred learning method was Team training in a full-scale simulation setup. The top three preferred learning methods for each learning goal are displayed in Table 4.

Discussion

In this Delphi study, we identified 57 learning goals of which 41 were rated relevant for scrub nurses, circulating nurses or RNFA working with RAS. The training method considered to be most relevant was Supervised training during surgery on patients

Competences concerning emergency undocking

It is essential that the OR nurses working with RAS have knowledge of the robotic system and equipment and especially how to handle an emergency situation during surgery [3] [7]. Knowing emergency un-docking procedures is essential in the event of a critical occurrence during surgery e.g. uncontrollable bleeding or cardiac arrest [6]. In RAS there will be a delay in getting access to the patient in case of an emergency due to the robotic arms being docked to the trocars in the patient and unfamiliarity with these procedures can cause a further delay of the emergency undocking with consequences for the patient safety.

In 52 out of the 57 learning goals, the panel were very much in agreement during the rating of the learning goals. In the domain “Technical Skills”, the learning goal: Safely change robotic instruments during procedure stood out as being one in a few that showed a relative disagreement in the panel. Only 61% of the panel, rated this learning goal as being Very relevant or Essential and with an IQR of 2 and a median of 4, the final rating of the learning goal was Relevant. The reason for the disagreement concerning this learning goal, might be that changing instruments during a procedure is not relevant for all RAS nurses in the sense that in some robotic teams, the changing of instruments is done by the surgeons. In the domain “Docking”, Dock the robot as part of the sterile team is another learning goal that split the panel. With only 46% of the panel finding this to be Very relevant or Essential, an IQR of 2 and a median of 3, the final rating of this learning goal was Not relevant. Like the above-mentioned learning goal, and for the same reasons, docking the robot is not relevant for all RAS nurses.

Interestingly, both learning goals are among the essential competencies all members of the robotic team need to master, to be able to participate in an emergency undocking procedure. If some of the RAS nurses in the panel are not used to changing instruments or docking the robot during procedures, it makes sense that they do not make the connection between these activities, to an emergency undocking procedure. This could be the reason for the relatively low ratings of Relevant and Not relevant. In such teams, there needs to be an awareness of how to train and maintain competencies needed in an emergency undocking procedure.

Communication

The Delphi panel submitted two learning goals concerning communication under the domain of Non-technical skills. Traditionally non-technical skills are defined as teamwork, situational awareness, and communication [15, 22] one of the main differences between traditional open or laparoscopic surgery and RAS is the console surgeon’s remote position, sitting in the console, away from the rest of the surgical team and the patient. With the robotic systems used at present, the surgeons are not only removed from the team but is also isolated with their heads in an ocular on the console [8, 9]. This setup challenges the robotic teams’ perioperative interactions concerning e.g. communication and especially the console surgeons’ situational awareness [10]. In a 2019 survey, a certain lack of awareness within the perioperative team, of the communication challenges in robotic surgery, was found [10] and according to Collins et al., there is a lack of training of NTS, such as communication, in existing robotic training curriculums, which may cause a risk to patient safety [15]. The Delphi panel of RAS nurses in this study is very much aware of communication in RAS, with 98% of them agreeing on the learning goal Communicate effectively with other team members, as being Very relevant or Essential. But with only 36% of the panel rating, the learning goal Explain the communication challenges in robotic surgery. (e.g. limited non-verbal communication with console surgeon) as being Very relevant or Essential there seems to be a lack of attention to training the communication challenges. Not unlike the other learning goals, the panel agree on Supervised training during surgery on patients, with the two above-mentioned learning goals on communication as being the preferred learning method closely followed by Team training in full-scale simulation setup.

Registered nurse first assistant

The role of the RNFA is defined as being an OR nurse, who has acquired knowledge, judgment, and skills specific to the expanded role as a first assistant [23]. An RNFA does not concurrently function as a scrub nurse, thereby taking on two different roles during the same procedure, with a risk of compromising patient safety. A discussion on the underutilization of the RNFA in British Columbia, compared to other regions in Canada, makes use of impact points such as a decrease in surgical site infections by up to 40% as well as a reduction of turnover time between patients [24]. Furthermore, a recent literature review on the role of the RNFA, shows that the perioperative team views the RNFA as a means to improve efficiency, reduce cost, and benefit patient safety [25]. The role of the RNFA was defined and included in the OR team in the United States in the early 1980s [23]. In Denmark, the first RNFA was included in RAS in 2010 at the Department of Urology, Aalborg University Hospital but the use of RFNAs is not standard in all hospitals. Three hospitals in Denmark use RNFA for robotic-assisted surgery while the remaining 12 hospitals performing RAS, does not.

Three of the learning goals under the domain of Technical skills concerned the handling of laparoscopic instruments during the procedure: Correctly use a laparoscopic suction, Safely insert laparoscopic instruments, Introduce suture materials (e.g. needles) into the abdomen using laparoscopic instruments. These learning goals might have been suggested by some of the 15% of RAS nurses in the Delphi panel, who also practice as RNFA. The final ratings of these learning goals were Not relevant, even though the data show, that some of the RAS nurses in the panel, who do not practice as an RNFA, still rated the learning goals as Very relevant or Essential. This is supported by the data from the additional round, where the panel rated these learning goals to be relevant for Scrub nurses by 44, 47, and 50%, respectively, while they agreed on rating all three goals relevant for RNFA, by 84%.

Our findings reflect the different roles RAS nurses can have in the operating team. The three, above mentioned, learning goals which compares with skills, traditionally reserved for doctors, are relevant for RFNA, but not for scrub nurses, as their roles differ. [21] When designing a curriculum for RAS nurses it is important to consider which roles the nurses have (scrub nurse, circulating nurse or RNFA) and remember that some nurses might have different roles during different procedures. Our study focused on the identification of relevant content for a curriculum for all RAS nurses, but RFNA might require a different more encompassing curriculum, which should be investigated further. Many Delphi studies used experts as panelists to get the opinion of the ones most experienced in the area, where we chose to include OR nurses with varying levels of experience. This could be seen as a limitation, however, when identifying content for education programs within healthcare we think it is important to get input from participants with a broad range of experience as less experienced practitioners might have a different perspective on what should be included. We did not to included robotic surgeons, although it could have been interesting to also have had their input on the educational needs of OR nurses for robotic surgery.

Learning methods

Unlike in other Scandinavian countries, Danish OR nurses are trained in a master–apprentice setup with the use of competence cards [26]. This corresponds well with Supervised training during surgery on patients, being the preferred learning method in this study. In a Delphi study on curricula for RAS surgeons, Hertz et al. found that the learning methods: virtual reality simulation and animal models were preferred for technical training supplemented by e-learning for theory and Team training for NTS [21]. In comparison, Wet-lab (hands-on training on live animals/cadavers) only made the top three of preferred learning methods, in 2 of the 57 learning goals while Virtual reality simulator training did not make the top three in any of the learning goals. These learning methods may be considered by the OR nurses in the Delphi panel, as being more targeted at doctors training for RAS, than for OR nurses and the learning goals in this study.

The overall preferred learning method of the OR nurses in the Delphi panel is Supervised training during surgery on patients. This method is well known by the panel, as the way, they were trained as OR nurses. Furthermore, most of the learning goals in this study are very technical and/or practical and thus might not be considered suitable for learning methods such as Virtual Reality simulation or Wet-lab.

The learning method e-learning only made the top three in 16 of the 57 learning goals while Team training in full-scale simulation setup made the top three of preferred learning methods in all of the learning goals under the domains of Emergency procedures and Non-technical skills. This shows that the OR nurses prefer specific learning methods for specific learning goals and with both ERUS, FRS, and SERGS recommending curricula to contain multiple learning methods, [13, 14, 27] it should be taken into consideration to supplement the panel’s preferred learning methods Supervised training during surgery on patients with Team training in full-scale simulation setup and e-learning.

We have identified a list of learning goals that can be used as the basis for designing a curriculum for OR nurses working with RAS. The learning goals span over different domains and the processing of them shows the importance of a continued focus on topics such as communication, emergency procedures, and awareness of different skill requirements depending on the role of the RAS nurse in the team. Furthermore, it is important to be aware of how the education of RAS nurses also requires the use of different learning methods than traditionally used in the education of OR nurses.

Data availability

The datasets used for this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Intuitive (2022) Intuitive announces preliminary fourth quarter and full year 2021 results. https://isrg.intuitive.com/news-releases/news-release-details/intuitive-announces-preliminary-fourth-quarter-and-full-year-1. Accessed 22 Jan 2022

Francis P (2006) The evolution of robotics in surgery and implementing a perioperative robotics nurse specialist role. AORN J. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-2092(06)60191-9

Kang MJ, De Gagne JC, Kang HS (2016) Perioperative nurses’ work experience with robotic surgery: a focus group study. Comput Inf Nurs 34:152–158. https://doi.org/10.1097/cin.0000000000000224

Abdel Raheem A, Song HJ, Chang KD, Choi YD, Rha KH (2017) Robotic nurse duties in the urology operative room: 11 years of experience. Asian J Urol 4:116–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajur.2016.09.012

Uslu Y, Altınbaş Y, Özercan T, van Giersbergen MY (2019) The process of nurse adaptation to robotic surgery: a qualitative study. Int J Med Robot Comput Assist Surg. https://doi.org/10.1002/rcs.1996

Carlos G, Saulan M (2018) Robotic emergencies: are you prepared for a disaster? AORN J 108:493–501. https://doi.org/10.1002/aorn.12393

Francis P, Winfield HN (2006) Medical robotics: the impact on perioperative nursing practice. Urol Nurs 26:99–104, 107–108

Tiferes J, Hussein AA, Bisantz A, Kozlowski JD, Sharif MA, Winder NM, Ahmad N, Allers J, Cavuoto L, Guru KA (2016) The loud surgeon behind the console: understanding team activities during robot-assisted surgery. J Surg Educ 73:504–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2015.12.009

Tiferes J, Hussein AA, Bisantz A, Higginbotham DJ, Sharif M, Kozlowski J, Ahmad B, O’Hara R, Wawrzyniak N, Guru K (2019) Are gestures worth a thousand words? Verbal and nonverbal communication during robot-assisted surgery. Appl Ergon 78:251–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2018.02.015

Almeras C (2019) Operating room communication in robotic surgery: place, modalities and evolution of a safe system of interaction. J Visc Surg 156:397–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2019.02.004

Fisher RA, Dasgupta P, Mottrie A, Volpe A, Khan MS, Challacombe B, Ahmed K (2015) An over-view of robot assisted surgery curricula and the status of their validation. Int J Surg 13:115–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.11.033

Ahmed K, Khan R, Mottrie A, Lovegrove C, Abaza R, Ahlawat R, Ahlering T, Ahlgren G, Artibani W, Barret E, Cathelineau X, Challacombe B, Coloby P, Khan MS, Hubert J, Michel MS, Montorsi F, Murphy D, Palou J, Patel V, Piechaud PT, Van Poppel H, Rischmann P, Sanchez-Salas R, Siemer S, Stoeckle M, Stolzenburg JU, Terrier JE, Thüroff JW, Vaessen C, Van Der Poel HG, Van Cleynenbreugel B, Volpe A, Wagner C, Wiklund P, Wilson T, Wirth M, Witt J, Dasgupta P (2015) Development of a standardised training curriculum for robotic surgery: a consensus statement from an international multidisciplinary group of experts. BJU Int 116:93–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.12974

ERUS robotic curriculum. European Association of Urology. https://uroweb.org/section/erus/education/. Accessed 22 Jan 2022

Fundamentals of robotic surgery. https://frsurgery.org/. Accessed 22 Jan 2022

Collins JW, Dell’Oglio P, Hung AJ, Brook NR (2018) The importance of technical and non-technical skills in robotic surgery training [figure presented]. Eur Urol Focus 4:674–676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euf.2018.08.018

Kern DE (2015) Curriculum development for medical education: a six-step approach. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore

Black N, Murphy M, Lamping D, Mckee M, Sanderson C, Askham J, Marteau T (2013) Consensus development methods, and their use in creating clinical guidelines. Adv Handb Methods Evid Based Healthc 2:426–448. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781848608344.n24

McMillan SS, King M, Tully MP (2016) How to use the nominal group and Delphi techniques. Int J Clin Pharm 38:655–662. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-016-0257-x

Jones J, Hunter D (1995) Qualitative research: consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ 311:376. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.311.7001.376

Hackett S, Masson H, Phillips S (2006) Exploring consensus in practice with youth who are sexually abusive: findings from a delphi study of practitioner views in the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland. Child Maltreat 11:146–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559505285744

Hertz P, Houlind K, Jepsen J, Bundgaard L, Jensen P, Friis M, Konge L, Bjerrum F (2021) Identifying curriculum content for a cross-specialty robotic-assisted surgery training program: a Delphi study. Surg Endosc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-021-08821-3

Berner JE, Ewertz E (2019) The importance of non-technical skills in modern surgical practice. Cir Esp 97:190–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ciresp.2018.12.007

Wan PAG (2019) RN first assistant (RNFA). In: J. Leg. Nurse Consult. http://www.aalnc.org/page/journal-v2.0. Accessed 24 Jan 2022

Bryant EA (2020) British Columbia’S underutilization of registered nurse first assists: a barrier to achieving the quadruple aim. ORNAC J 38:15–30

Pika R, O’Brien B, Murphy J, Markey K, O’Donnell C (2021) The role of the registered nurse first assistant within the perioperative setting. Br J Nurs 30:148–153. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2021.30.3.148

Holbæk E (2021) DSR. https://dsr.dk/fs/fs2/kompetencekort. Accessed 22 Jan 2022

Rusch P, Kimmig R, Lecuru F, Persson J, Ponce J, Degueldre M, Verheijen R (2018) The society of European robotic gynaecological surgery (SERGS) pilot curriculum for robot assisted gynecological surgery. Arch Gynecol Obstet 297:415–420. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-017-4612-5

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the participants in the Delphi panel, their departments and hospitals: Rigshospitalet, Herlev Hospital, Zealand University Hospital, Slagelse Hospital, Aalborg University Hospital, Aarhus University Hospital, Region Hospital Herning, Region Hospital Holstebro, Odense University Hospital, Hospital Sønderjylland, Lillebaelt Hospital, and Hospital of South West Jutland.

Funding

This study is funded by CAMES, Copenhagen Academy for Medical Education and Education, Center for HR and Education, and The Capital Region of Denmark. No external funding was received for the work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

OR nurses Louise Møller, Ulla Grande, Janne Aukdal, Britt Fredensborg, Helle Kristensen, and Jane Petersson and Drs. Peter Hertz, Flemming Bjerrum, and Lars Konge have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Ethical approval

The study was submitted to the Scientific Ethics Committees of the Capital Region, Denmark, which found that ethical approval was not required (Journal No. H-20074884). All participants gave informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Møller, L., Hertz, P., Grande, U. et al. Identifying curriculum content for operating room nurses involved in robotic-assisted surgery: a Delphi study. Surg Endosc 37, 2729–2748 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-022-09751-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-022-09751-4