Abstract

Background

Restorative proctocolectomy with ileal J pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA) has become the standard of care for mucosal ulcerative colitis and Familial Adenomatous Polyposis. Some patients require re-operation, including pouch revision, advancement, or excision. Re-operative procedures are technically demanding and usually performed only by experienced colorectal surgeons in a small number of referral centers. There is a paucity of data regarding feasibility, safety, and outcomes of laparoscopic re-operative IPAA surgery. This study aimed to determine the safety and feasibility of laparoscopic approach for re-operative IPAA, trans-abdominal surgery.

Methods

Retrospective analysis of IRB-approved prospective database for patients who underwent trans-abdominal re-operative IPAA from 2011 to 2018. Patient demographics and operative reports were reviewed to classify type of re-operation into pouch excision, revision, or advancement and further classify as laparoscopic, laparoscopic converted to open, or open surgery. Main outcome measures were post-operative morbidity and mortality.

Results

Seventy-six patients met the inclusion criteria: 19 underwent attempted laparoscopic re-operative IPAA surgery, 12 of whom underwent successful laparoscopic surgery while 7 were converted to laparotomy, for an overall laparoscopic intent to treat 63% success rate. The remaining operations (n = 57) were performed through midline laparotomy. Length of stay (LOS) for patients who underwent laparoscopic surgery was significantly shorter (5.5 vs 9.7 days, p < 0.001) as were abdominal superficial surgical site infections (SSI) (0% vs 18%, p < 0.001) and deep SSI (0% vs 17%, p < 0.001). Laparotomy was performed by 6 colorectal surgeons at our institution while laparoscopy was successfully performed only by the senior author. There was no significant difference in overall complications, re-admission, re-operation, or mortality.

Conclusion

Re-operative, trans-abdominal, laparoscopic IPAA is both feasible and safe and has clear benefits compared to laparotomy in terms of LOS and superficial and deep SSI. However, this approach needs to be undertaken only by very experienced, high-volume laparoscopic IPAA surgeons.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Total proctocolectomy is the surgical treatment for a variety of medical conditions including mucosal ulcerative colitis (MUC) and familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) syndrome. Following removal of the colon and rectum, there are several options for fecal evacuation including end ileostomy, continent ileostomy, ileorectal anastomosis, or restorative proctocolectomy. Restoration of gastrointestinal continuity, also known as ileoanal anastomosis, can be created using different configurations and is possible if the anal sphincter complex is anatomically and functionally preserved. The various types of reconstruction include straight anastomosis, S pouch, W pouch or J pouch configuration. The IPAA J pouch has become the global standard of care. However, long-term complications occur in 25–60% of patients including pouchitis, pouch dysfunction, pouch stricture, fistulization, neoplasia and pouch prolapse; up to 15% of pouches will eventually fail. [1,2,3,4,5,6] These potential complications can be indications for IPAA re-operation, with the main risk factors for pouch excision being pelvic sepsis and Crohn’s disease (CD). [7,8,9,10,11,12] The rate of re-operative procedures following IPAA is 10–20% and include pouch revision, pouch advancement, and pouch excision. Re-operative procedures are technically demanding and are usually performed by experienced colorectal surgeons in a small number of referral centers. Peri-operative morbidity following re-operation is considerable, with reported short-term complication rates between 30 and 50%. The long-term pouch failure rate following IPAA re-operation is 20–30%. [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20].

There are scarce data regarding the feasibility, safety, and outcomes of laparoscopic re-operative IPAA surgery. Therefore, we present our series of trans-abdominal re-operative IPAA surgery with emphasis on the surgical approaches and their outcomes.

Methods

A retrospective analysis of an IRB-approved prospective data base was performed. All patients who underwent trans-abdominal re-operative IPAA surgery for MUC or FAP from 2011 to 2018 were included. Patients who underwent primary IPAA surgery, patients who had trans-perineal re-operative IPAA surgery, and patients with pouches who underwent surgery for indications other than pouch-related problems were excluded. Patient demographics, surgical indications, and diagnoses were evaluated, and operative reports were reviewed to classify the type of re-operation including the following:

-

Pouch excision: abdominoperineal excision of the pouch and creation of end ileostomy. This operation is a combination of trans-abdominal approach to completely mobilize all loops of small bowel and the IPAA pouch and trans-perineal approach to complete the dissection of the intralevator aspect of the pouch and excision of the anus.

-

Pouch revision: trans-abdominal mobilization of the pouch, creation of a new pouch or resection of part of the pouch and re-anastomosis followed by creation of diverting loop ileostomy.

-

Pouch advancement: abdominoperineal mobilization of the pouch and re-anastomosis followed by creation of diverting loop ileostomy.

A trans-abdominal pelvic drain was placed in all patients and removed prior to hospital discharge. All patients had an ileostomy either prior to or created at the re-operation IPAA surgery.

The approach to the abdominal portion of the surgery was classified as laparoscopic, laparoscopic converted to open, or open surgery. The decision to convert to laparotomy in all cases was done after placement of at least 3 trocars and thorough diagnostic laparoscopy. Conversions to laparotomy were classified as preemptive or reactive [21], as previously discussed. The decision to start the case in laparoscopy or laparotomy was surgeon’s preference. Data on patients who underwent conversion of laparoscopy to laparotomy were analyzed within the laparotomy group. The post-operative course was reviewed for length of stay (LOS), post-operative complications, re-admission, emergency re-operation, and mortality. Statistical analysis of the collected data was performed. Fisher's exact and chi-square tests were used for categorical variables and the t-student test for continuous data. All analyses were conducted with SPSS statistical software.

For the purpose of this study, a “high-volume” pouch surgeon is defined as a surgeon who performs ≥ 20 pelvic pouch operations each year.

Results

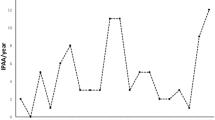

Seventy-six patients met the inclusion criteria including 32 females (44%), of a mean age of 47.6 years and a mean body mass index (BMI) of 24 kg/m2. The reason for re-operation was septic complication in 32 patients (42%) including chronic anastomotic leak, chronic pelvic abscess, or perineal sepsis. Other reasons for re-operation were pouch dysfunction, fistulizing Crohn’s disease of the pouch, incontinence, and carcinoma in 27, 12, 5, and 3 patients, respectively. The senior author (SDW) performed 52 IPAA re-operations including 36 laparotomies, 4 laparoscopy converted to laparotomy, and 12 laparoscopies (4/16; 25% conversion rate). The second surgeon performed 13 IPAA re-operations including 10 laparotomies and 3 conversions (3/3, 100% conversion rate) and the remaining 4 surgeons collectively performed 11 IPAA re-operations all by laparotomy. Overall, 12 patients underwent laparoscopic surgery, 7 patients underwent laparoscopy converted to laparotomy, and 57 patients had standard laparotomy surgery. Thus, the overall rate of successfully completing laparoscopic IPAA re-operation was 63% (75% for the senior author and 0% for the other surgeon). Overall, 12/76 underwent successful laparoscopic IPAA re-operation (16% institutional success rate). Reasons for conversion were preemptive in all 7 patients: severe dense adhesions of small bowel loops in 4 patients, severe chronic pelvic fibrosis in 2 patients and distended small bowel loops in 1 patient (Table 1). There was an increasing trend of performing laparoscopic re-operation IPAA between 2011 and 2018. In 2011 and 2012 there were no laparoscopic attempts for IPAA re-operations while in 2018–31% (5/16) IPAA re-operations were laparoscopically undertaken (Fig. 1). The index IPAA surgery was laparoscopic in 59/76 cases; the mean time period between the index pouch operation and the re-operation was 9.7 years (Range 1–35)0.31 patients had undergone their index pouch operation by surgeons in our department and 45 patients were referred to surgeons in our department following index IPAA surgery elsewhere. The types of re-operative procedures included excision, advancement, and revision in 76%, 14.5%, and 17%, respectively. The mean length of operation was 291 min. The mean LOS was 9 days and the re-admission, re-operation, and mortality rates were 17%, 14.5%, and 0%, respectively. The overall complication rate was 51% with the most common peri-operative complications being superficial and deep surgical site infection (SSI) (Table 2).

There was no difference between laparoscopy and laparotomy relative to age, gender, BMI, prior surgical approach, location of prior surgery, or time period between the IPAA creation and re-operation, indication for surgery, and type of re-operative surgery (Table 3). The benefits of laparoscopy included significant reduction in LOS (5.5 vs 9.7 days, p < 0.001), abdominal superficial SSI (0% vs 17%, p < 0.001), and abdominal deep SSI (0% vs 17%, p < 0.001) as compared to laparotomy. There were no significant differences in length of operation, overall complications, perineal SSI, re-admission, re-operation, or mortality (Table 4).

Discussion

Although restorative proctocolectomy with IPAA has become the standard of care, it is associated with significant short- and long-term morbidity. [1,2,3,4,5] While re-operative IPAA surgery has high success rates, it is also associated with high morbidity rates. [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20, 22, 23] In our series, 51% of patients had at least one complication with no mortality, which is in concordance with the current literature. Remzi et al. [14] reported their experience in 500 IPAA re-operations including creation of a new pouch in 41% and pouch revision in 59%. In their series, overall morbidity, leak, and mortality rates were 53%, 8%, and 0%, respectively. At a median follow-up of 7 years after redo surgery, 20% of patients had redo IPAA failure. [14] Laparoscopy was not mentioned presumably because it was not performed in any patient.

The benefits of laparoscopic IPAA surgery are well documented and include shorter LOS, lower morbidity, and faster recovery, as well as a better cosmetic outcome. [24,25,26,27,28,29] Although prior series have reported rates of complications and other outcome measures following re-operative trans-abdominal IPAA surgery, there are no series that comparing the laparoscopic to the open approach. In our series, clear benefits for laparoscopic IPAA re-operation were demonstrated including shorter LOS, less superficial surgical site infection and less deep surgical site infection. It may be that both SSI and post-operative pain following laparotomies contributed to the longer LOS. In our series, 7 patients underwent laparoscopic converted to open redo IPAA surgery and the reasons for conversion were extensive dense adhesions, distended loops of small bowel and extensive fibrosis of and around the pouch. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the information regarding the exact timing of the surgeon’s decision during the laparoscopic operation to convert is lacking. However, according to the operative reports, all conversions were preemptive and none were reactive. [30] The decision to convert from laparoscopy to laparotomy should be made following a thorough exploration of the abdomen and pelvis. For the most part, an experienced surgeon can decide upon the feasibility of the laparoscopic procedure after the exploratory phase and should not spend time afterwards with unnecessary dissection that might create iatrogenic damage.

Thus, a sound clinical judgment by a surgeon who is experienced in laparoscopic J pouch surgery is crucial to the success. The lack of surgical site infection suggests that the advantages of laparoscopic surgery persist and may be comparatively enhanced in complex re-operative procedures.

There are several limitations to this study including the relatively small number of procedures, especially laparoscopic, the retrospective nature of the study, and the fact that multiple surgeons performed the operations by laparotomy but only one surgeon completed it by laparoscopy. Thus, a potential selection bias to perform laparoscopy was the surgeon performing the operation. In addition, we do not have information related to the duration of pre-operative antibiotics use or pre-operative duration of pelvic sepsis. Another limitation is the absence of strict criteria by w hich laparoscopy was selected. However, as the senior author gained experience, patients who were not obese, did not have recurrent pelvic sepsis, did not have a ventral incisional hernia in need of repair, and had < 3 prior laparotomies or laparoscopic operations performed were considered candidates for laparoscopic IPAA re-operation. Over time, the indications increased to exclude only patients in whom a ventral incisional hernia repair was planned at the time of redo IPAA surgery.

A prospective, larger study is required to further elucidate the role of laparoscopy in these highly demanding surgeries and to try and delineate which patients would be the most appropriate candidates.

Conclusion

Re-operative trans-abdominal laparoscopic IPAA surgery is both feasible and safe. It offers clear benefits of a shorter LOS and lower rates of superficial and deep surgical site infection. However, this approach should be undertaken only by very experienced, high-volume laparoscopic IPAA surgeons.

References

Fazio VW, Kiran RP, Remzi FH et al (2013) Ileal pouch anal anastomosis: analysis of outcome and quality of life in 3707 patients. Ann Surg 257:679–685

Ozdemir Y, Kiran RP, Erem HH et al (2014) Functional outcomes and complications after restorative proctocolectomy and ileal pouch anal anastomosis in the pediatric population. J Am Coll Surg 218:328–335

Fazio VW, Ziv Y, Church JM et al (1995) Ileal pouch-anal anastomoses complications and function in 1005 patients. Ann Surg 222:120–127

Meagher AP, Farouk R, Dozois RR, Kelly KA, Pemberton JH (1998) J ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis: complications and long-term outcome in 1310 patients. Br J Surg 85:800–803

Fazio VW, O’Riordain MG, Lavery IC et al (1999) Long-term functional outcome and quality of life after stapled restorative proctocolectomy. Ann Surg 230:575–586

Tekkis PP, Lovegrove RE, Tilney HS et al (2010) Long-term failure and function after restorative proctocolectomy - a multi-center study of patients from the UK National Ileal Pouch Registry. Colorectal Dis 12:433–441

Nisar PJ, Kiran RP, Shen B, Remzi FH, Fazio VW (2011) Factors associated with ileoanal pouch failure in patients developing early or late pouch-related fistula. Dis Colon Rectum 54:446–453

Manilich E, Remzi FH, Fazio VW, Church JM, Kiran RP (2012) Prognostic modeling of preoperative risk factors of pouch failure. Dis Colon Rectum 55:393–399

Tekkis PP, Fazio VW, Remzi F, Heriot AG, Manilich E, Strong SA (2005) Risk factors associated with ileal pouch-related fistula following restorative proctocolectomy. Br J Surg 92:1270–1276

Fazio VW, Tekkis PP, Remzi F et al (2003) Quantification of risk for pouch failure after ileal pouch anal anastomosis surgery. Ann Surg 238:605–617

Melton GB, Fazio VW, Kiran RP et al (2008) Long-term outcomes with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis and Crohn’s disease: pouch retention and implications of delayed diagnosis. Ann Surg 248:608–616

Shen B, Fazio VW, Remzi FH et al (2006) Risk factors for clinical phenotypes of Crohn’s disease of the ileal pouch. Am J Gastroenterol 101:2760–2768

Lightner AL, Shogan BD, Mathis KL et al (2018) Revisional and reconstructive surgery for failing IPAA is associated with good function and pouch salvage in highly selected patients. Dis Colon Rectum 61:920–930

Remzi FH, Aytac E, Ashburn J et al (2015) Transabdominal redo ileal pouch surgery for failed restorative proctocolectomy: lessons learned over 500 patients. Ann Surg 262:675–682

Pellino G, Selvaggi F (2015) Outcomes of salvage surgery for ileal pouch complications and dysfunctions. The experience of a referral center and review of literature. J Crohns Colitis 9:548–557

Shawki S, Belizon A, Person B, Weiss EG, Sands DR, Wexner SD (2009) What are the outcomes of reoperative restorative proctocolectomy and ileal pouch-anal anastomosis surgery? Dis Colon Rectum 52:884–890

Remzi FH, Fazio VW, Kirat HT, Wu JS, Lavery IC, Kiran RP (2009) Repeat pouch surgery by the abdominal approach safely salvages failed ileal pelvic pouch. Dis Colon Rectum 52:198–204

Tulchinsky H, Hawley PR, Nicholls J (2003) Long-term failure after restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. Ann Surg 238:229–234

Baixauli J, Delaney CP, Wu JS, Remzi FH, Lavery IC, Fazio VW (2004) Functional outcome and quality of life after repeat ileal pouch anal anastomosis for complications of ileoanal surgery. Dis Colon Rectum 47:2–11

Lightner AL, Dattani S, Dozois EJ, Moncrief SB, Pemberton JH, Mathis L (2017) Pouch excision: indications and outcomes. Colorectal Dis 19:912–916

Yang C, Wexner SD, Safar B, Jobanputra S, Jin H, Li VK, Nogueras JJ, Weiss EG, Sands DR (2009) Conversion in laparoscopic surgery: does intraoperative complication influence outcome? Surg Endosc 23(11):2454–2458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-009-0414-6

Larson DW (2014) Revision IPAA: Strategies for success. J Gastrointest Surg 18:1236–1237

Holubar SD, Neary P, Aiello A et al (2019) Ileal pouch revision vs excision: short-term (30-day) outcomes from the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Colorectal Dis 21(2):209–218

Baek S-J, Dozois EJ, Mathis KL et al (2016) Safety, feasibility, and short-term outcomes in 588 patients undergoing minimally invasive ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: a single-institution experience. Tech Coloproctol 20:369–374

Marcello PW, Milsom JW, Wong SK et al (2000) Laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy: case-matched comparative study with open restorative proctocolectomy. Dis Colon Rectum 43:604–608

Larson DW, Dozois EJ, Piotrowicz K et al (2005) Laparoscopic-assisted vs open ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: functional outcome in a case-matched series. Dis Colon Rectum 48:1845–1850

Hata K, Kazama S, Nozawa H et al (2015) Laparoscopic surgery for ulcerative colitis: a review of the literature. Surg Today 45:933–938

Sardinha TC, Wexner SD (1998) Laparoscopy for inflammatory bowel disease: pros and cons. World J Surg 22:370–374

Schmitt SL, Cohen SM, Wexner SD, Nogueras JJ, Jagelman DG (1994) Does laparoscopic-assisted ileal pouch anal anastomosis reduce the length of hospitalization? Int J Colorectal Dis 9:134–137

Yang C, Wexner SD, Safar B, Jobanputra S, Jin H, Li VK, Nogueras JJ, Weiss EG, Sands DR (2009) Conversion in laparoscopic surgery: does intraoperative complication influence outcome? Surg Endosc 23(11):2454–2458

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

Shlomo Yellinek, Hayim Gilshtein, Dimitri Krizzuk, and Steven D. Wexner have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yellinek, S., Gilshtein, H., Krizzuk, D. et al. Re-operation surgery following IPAA: is there a role for laparoscopy?. Surg Endosc 35, 1591–1596 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-020-07537-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-020-07537-0