Abstract

Background

To investigate the safety and feasibility of the completely medial access by page-turning approach (CMAP) for laparoscopic right hemi-colectomy.

Methods

In this retrospective study, the data from 72 patients who underwent laparoscopic right hemi-colectomy with CMAP were analyzed and compared with data from 124 patients who underwent the conventional medial approach performed by the same surgical team from September 2011 to March 2017.

Result

Complete mesocolic excision (CME) was achieved in 67 of 72 patients (93.1%) with laparoscopic CMAP. The average operation time, blood loss, and specimen length was 135.9 ± 28.3 min, 63.2 ± 32.2 ml, and 23.9 ± 4.7 cm, respectively. The number of lymph nodes harvested was 20.6 ± 7.7, the time-to-flatus was 2.5 ± 0.8 days, the time-to-fluid intake was 3.2 ± 0.8 days, and the average hospital stay was 8.9 ± 4.7 days. No intra-operative complications occurred in this study. The vessel-related complication and total post-operative complication rate was 2.78% (2/72) and 6.94% (5/72), respectively.

Conclusions

Laparoscopic CMAP was an alternative approach for CME in laparoscopic right hemi-colectomy, which was proved safe and feasible for right colon cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Based on the concept of total meso-rectal excision (TME), which is now the standard approach for rectal cancer [1]. Prof. Hohenberger developed complete mesocolic excision (CME) for colon cancer, stating that the mesocolon is covered by an envelope composed of visceral and parietal fascia. The technical strategies for CME include the following: separation of visceral and parietal fascia; central ligation of vessels; and radical lymphadenectomy. In the Hohenberger study [2], the patients who underwent CME had a lower local recurrence rate (6.5% vs. 3.5%) and better survival rate (82.1% vs. 89.1%). Other studies have supported this result [3,4,5,6]. It is widely accepted that laparoscopic CME is comparable with open surgery in terms of the radicality, pathology, and oncologic outcome, and even better with respect to short-term outcomes (especially pain, blood loss, and complications) [7, 8].

CME is often characterized by two major access(lateral-to-medial access and medial-to-lateral access) [9]. The medial-to-lateral approach is traditionally adopted in laparoscopic CME for right colon cancer. Due to the surgical complexity of the right colon, such as searching for surgical planes, locating tributaries of the superior meso-colic vein (SMV), and avoiding bleeding from Henle’s trunk, the standard CME is more difficult to achieve during laparoscopic right hemi-colectomy than laparoscopic left hemi-colectomy. To address these problems, various laparoscopic and open techniques have been described in the literature, as follows: uncinate process first approach; initial retrocolic endoscopic tunnel approach; or suprapubic approach [10,11,12,13]. Based on our previous work, we presented this optimized CME approach (completely medial access by page-turning approach [CMAP]), which has been shown to be safe and feasible.

Methods

Patients

This retrospective study involved 72 patients who underwent laparoscopic CMAP due to right colon cancer and 124 patients who underwent a conventional medial approach between September 2011 and March 2017 by the same surgical team. All patients provided informed consent and this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine.

The inclusion criteria for patients were as follows: (1) pathologically confirmed with carcinoma of the cecum, ascending colon, or hepatic flexure; (2) pathological tumor staging was stage I, II, and III according to the 7th edition of the UICC tumor classification; (3) tumor diameter < 7 cm; and (4) underwent laparoscopic right hemi-colectomy. Patients were excluded for the following reasons: (1) presence of distant metastases; (2) synchronous or double primary cancer; and (3) emergency.

Surgical techniques

The preparation for surgery, patient position, surgeon location, and insertion of trocars were the same as previously reported [14]. All of the procedures complied with the principle of laparoscopic CME. Related videos were shown in Supplement Video 1.

Key steps for CMAP (Figs. 1, 2):

The surgical procedures of CMAP. A Start point: Projection of ileocolic vessel, to confirm the location of superior mesenteric vein(SMV); B Dissection of surgical trunk: Expose the whole trunk of SMV to the level of inferior edge of pancreas before ligating any branches; C Exploration of surgical plane: Enter to IMS and RRCS with cranial extension through TRCS, keep the mesocolon intact; D Dissection of vessels before removing the tumor en-bloc

-

1.

Starting point Take the projection of ileocolic vessel as the starting point, and confirm the location of SMV;

-

1)

Dissection of the SMV Expose the entire trunk of the SMV up to the level of the inferior edge of the pancreas before ligating any branches for the purpose of verifying the location;

-

2)

Exploration of the surgical plane Enter the intermesenteric space (IMS) and right retro-colic space (RRCS) with cranial extension through the transverse retro-colic space (TRCS);

-

3)

Removal of the mesocolon Mobilize the mesocolon completely and remove the tumor en bloc.

All of the surgical steps are conducted as if turning pages (Fig. 1).

Operation and pathology assessment

Videos of the operation and and photographs of the specimen were recorded for assessing the quality of the surgery and CME by three independent professional observers, according to the grading system introduced by West et al. [15], as follows: (1) mesocolic plane (good plane of surgery; intact mesocolon with a smooth peritoneal-lined surface); (2) intramesocolic plane (moderate plane of surgery; partial mesocolon with irregularity, but the incision do not reach the muscularis propria); (3) muscularis propria plane (poor plane of surgery; little mesocolon with incision extending down to the muscularis propria).

The following data were also recorded: operation time; blood loss; number of lymph nodes harvested; length of specimen; time-to-anal exsufflation; time-to-liquid diet intake; duration of hospital stay; and complications and mortality within 30 days.

The pathology-related outcomes were assessed and recorded by pathologists in the Pathology Department, including histologic TNM stage, grades of differentiation, length of specimen, and number of lymph nodes harvested, etc.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables were described with the mean ± standard deviation or median. Differences in variables were analyzed using Student’s t test and χ2 test. All data were analyzed using SPSS software (version 15.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) with a significance level set at p < 0.05.

Results

Seventy-two patients (40 males and 32 females) diagnosed with right colon cancer underwent laparoscopic CMAP. There were 14, 31, and 27 patients diagnosed with carcinoma of the cecum, ascending colon, and hepatic flexure, respectively. There were 8 poorly differentiated cases, 50 medium-differentiated cases, 11 well-differentiated cases, 2 adenocarcinoma combined with myxadenocarcinoma, and 1 signet ring cell carcinoma. The median age of patients was 65 years (range 37–80 years). The median BMI was 21 kg/m2 (range 16–39 kg/m2). There was no significant difference between the CMAP and control groups (Table 1).

For the quality of the specimens in the laparoscopic CMAP group, 67 (93.1%) cases belonged to the mesocolic plane and 5 (6.9%) cases belonged to the intramesocolic plane. The average operation time was 135.9 ± 28.3 min, the average blood loss was 63.2 ± 32.2 ml, the average length of specimen was 23.9 ± 4.7 cm, the number of lymph nodes harvested was 20.6 ± 7.7, the time-to-flatus was 2.5 ± 0.8 days, the time-to-liquid intake was 3.2 ± 0.8 days, and the average hospital stay was 8.9 ± 4.7 days. There was no significant difference between the CMAP and control groups, except that the blood loss was significantly less in the CMAP group (p < 0.01; Table 2).

There were no intra-operative complications, i.e., ureter injury, gastrointestinal damage, and subcutaneous emphysema. The vessel-related complication and total post-operative complication rate of CMAP and control group was 2.78% versus 5.65%, 6.94% versus 8.87%, respectively. All of the patients with complications were treated conservatively, except one patient required re-operation in the CMAP group because of gastric epiploic vessel bleeding. No patients died during the study.

Discussion

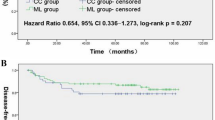

Curative surgery is standard treatment for colorectal cancer patients. Although it is widely known that CME is based on the anatomy of the mesocolon, there are few studies describing the accurate anatomic structures, which is of great significance for surgeons performing CME. Culligan et al. [16] formally characterized the mesocolic anatomy for the first time as continuous from the ileocecal to rectosigmoid level based on both macroscopic and microscopic findings. The mesocolon was separated from the retroperitoneum by mesothelial and connective tissue layers (i.e., Toldt’s fascia), which forms the ideal surgical plane for CME and explains the better clinical outcome of CME. There is a global consensus that CME has a lower local recurrence rate and a better survival rate. In a recent study, Bertelsen et al. [17] demonstrated that CME was a significant independent predictive factor for higher disease-free survival (DFS). Based on propensity score matching, the 4-year DFS after CME and non-CME was 85.8% and 73.4%, respectively. Laparoscopic CME is suggested as the gold standard approach for colon cancer as CME provides better short-term outcomes and comparable long-term survival with open surgery.

Our team reported the feasibility and technical strategies of laparoscopic CME in 2012 [9], followed by two approaches for medial access [18] [hybrid medial approach (HMA) and completely medial approach (CMA)]. After accurate identification of the surgical planes and spaces, CMA provided a shorter operation time and fewer vessel-related complication; however, during our following laparoscopic CME for right colon cancer, some difficulties arose: (1) Surgeons may face the technical limitations of a “leverage” or “tunnel” effect during the operation, which means some important structures might be jeopardized involuntarily during the operation. (2) There are anatomic variations of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and SMV branches, especially Henle’s trunk (HT). All of the tributaries must be recognized before dissection and ligation. (3) RRCS and TRCS are the most important surgical planes in CME for right colon cancer. It will be easier and safer to ligate the vessels and mobilize the bowel after fully exploring the RRCS and TRCS. After all these, CMAP was commenced in our center since 2011.

This study demonstrated that the intactness of the mesocolon was achieved in 93.1% (67/72) of patients, comparable to other reports 86–94% [7, 13, 19]. West [5, 6, 15] first emphasized that the mesocolic plane was correlated with DFS and overall survival (OS) and a lower local recurrence rate, showing a 15% 5-year OS advantage with the mesocolic plane compared with the muscularis propria plane based on univariate analysis, especially obvious for stage III patients with a 27% survival advantage at 5 years. Poorer prognosis was attributed to the intramesocolic plane and muscularis propria plane of surgery, suggesting the indispensable role of an intact mesocolon during CME surgery.

The number of harvested lymph nodes is critical for tumor staging, post-operative management, and prognosis [20]. Approximately, 25% of stage I and II colorectal cancer patients passed away because of an unexpected recurrence [21]. In addition to technical restrictions in examination of the specimen, there is a great possibility that lymph node metastases still exist in vivo. Thus, adequate lymphadenectomy is associated with better survival. Our results show that the mean number of lymph nodes harvested in the CMAP group was 20.6 ± 7.7, which was not significantly different from the control group, and consistent with other studies, ranging from 19 to 32 [7, 19] .

While the surgical anatomy is simple in patients with left colon cancer, the adoption of laparoscopic CME for right colon cancer is still a challenge and it requires advanced skills because of complex embryologic fusions and variable venous tributaries, especially Henle’s trunk, which is the major reason of intra-operative bleeding during surgery [22, 23]. Recently, the use of CT vascular mapping has been proven helpful and informative for colon surgery, indicating a high specificity, sensitivity, accuracy, and reliability [24,25,26]. However, the CT mapping is time-consuming and not cost-effective. Therefore, we do not routinely conduct pre-operative CT vascular mapping for colon cancer in our center.

There are five tributaries that might join to Henle’s trunk: anterior superior pancreaticoduodenal vein (ASPDV), right gastroepiploic vein (RGEV), superior right colic vein (SRCV), right colic vein (RCV), and middle colic vein (MCV) [24, 27]. It is necessary to recognize the origin of vessels before ligation to avoid troublesome bleeding. The ileocolic artery/vein (ICA/ICV) is always thought to be anatomically constant, which serves as a landmark to locate the SMA/SMV [28]; however, it is not easy for novices to locate the vessel pedicle when variations exist. In one case during the study, the SMV was mistaken for the ICV as the SMV shared a similar course with the ICV. By performing CMAP with a thorough exploration of surgical spaces, a disastrous complication was avoided (Supplement Video 2). Based on our experience, CMAP might be helpful for the following:

-

1)

avoid the laparoscopic “leverage effect” and “tunnel effect”;

-

2)

make tributaries of superior mesenteric vessels more easily recognized;

-

3)

offer an alternative route entering the TRCS, IMS, and RRCS;

-

4)

avoid repetitive flipping of the colon complying with the “no touch” principle, and lower the requirement of the assistant.

Besides, the blood loss was significantly reduced in CMAP (p < 0.01; Table 2). This could be associated with lower incidence of vessel related complications in CMAP group, although no significant difference (2.78% vs. 5.65%, p = 0.35; Table 2). According to our results, we suggested after fully exploring the surgical plane, it would be clearer and more accurate to recognize all the vessel distributions of the SMV/SMA before dissection and ligation.

CMAP is an optimized approach, which represents our understanding of CME and related surgical anatomy. As this study was retrospective with a limited number of cases, the preliminary difference here might be affected by other factors.

Conclusion

According to the results of this study, the CMAP was safe and feasible for right colon cancer, and was an alternative approach for CME. Except that the blood loss was significantly reduced in CMAP group, there was no other objective evidence of advantages of CMAP. However, we found the CMAP was a reasonable approach especially for patients whose surgical plane was difficultly recognized. Further randomized prospective trials with larger samples and long-term outcomes are needed to provide more convincing results.

References

Heald RJ (1988) The ‘Holy Plane’ of rectal surgery. J R Soc Med 81(9):503–508

Hohenberger W, Weber K, Matzel K, Papadopoulos T, Merkel S (2009) Standardized surgery for colonic cancer: complete mesocolic excision and central ligation–technical notes and outcome. Colorectal Dis 11(4):354–364. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01735.x discussion 364–355.

Kontovounisios C, Kinross J, Tan E, Brown G, Rasheed S, Tekkis P (2015) Complete mesocolic excision in colorectal cancer: a systematic review. Colorectal Dis 17(1):7–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.12793

Mori S, Kita Y, Baba K, Yanagi M, Tanabe K, Uchikado Y, Kurahara H, Arigami T, Uenosono Y, Mataki Y, Okumura H, Nakajo A, Maemura K, Natsugoe S (2017) Laparoscopic complete mesocolic excision via combined medial and cranial approaches for transverse colon cancer. Surg Today 47(5):643–649. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-016-1409-2

West NP, Hohenberger W, Weber K, Perrakis A, Finan PJ, Quirke P (2010) Complete mesocolic excision with central vascular ligation produces an oncologically superior specimen compared with standard surgery for carcinoma of the colon. J Clin Oncol 28(2):272–278. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.24.1448

West NP, Kobayashi H, Takahashi K, Perrakis A, Weber K, Hohenberger W, Sugihara K, Quirke P (2012) Understanding optimal colonic cancer surgery: comparison of Japanese D3 resection and European complete mesocolic excision with central vascular ligation. J Clin Oncol 30(15):1763–1769. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.38.3992

Adamina M, Manwaring ML, Park KJ, Delaney CP (2012) Laparoscopic complete mesocolic excision for right colon cancer. Surg Endosc 26(10):2976–2980. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-012-2294-4

Storli KE, Sondenaa K, Furnes B, Eide GE (2013) Outcome after introduction of complete mesocolic excision for colon cancer is similar for open and laparoscopic surgical treatments. Digest Surg 30(4–6):317–327. https://doi.org/10.1159/000354580

Feng B, Sun J, Ling TL, Lu AG, Wang ML, Chen XY, Ma JJ, Li JW, Zang L, Han DP, Zheng MH (2012) Laparoscopic complete mesocolic excision (CME) with medial access for right-hemi colon cancer: feasibility and technical strategies. Surg Endosc 26(12):3669–3675. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-012-2435-9

Benz S, Tam Y, Tannapfel A, Stricker I (2016) The uncinate process first approach: a novel technique for laparoscopic right hemicolectomy with complete mesocolic excision. Surg Endosc 30(5):1930–1937. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-015-4417-1

Matsuda T, Iwasaki T, Mitsutsuji M, Hirata K, Maekawa Y, Tsugawa D, Sugita Y, Sumi Y, Shimada E, Kakeji Y (2015) Cranially approached radical lymph node dissection around the middle colic vessels in laparoscopic colon cancer surgery. Langenbeck Arch Surg 400(1):113–117. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-014-1250-2

Petz W, Ribero D, Bertani E, Borin S, Formisano G, Esposito S, Spinoglio G, Bianchi PP (2017) Suprapubic approach for robotic complete mesocolic excision in right colectomy: Oncologic safety and short-term outcomes of an original technique. Eur J Surg Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2017.07.020

Subbiah R, Bansal S, Jain M, Ramakrishnan P, Palanisamy S, Palanivelu PR, Chinusamy P (2016) Initial retrocolic endoscopic tunnel approach (IRETA) for complete mesocolic excision (CME) with central vascular ligation (CVL) for right colonic cancers: technique and pathological radicality. Int J Colorectal Dis 31(2):227–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-015-2415-3

Zheng MH, Feng B, Lu AG, Li JW, Wang ML, Mao ZH, Hu YY, Dong F, Hu WG, Li DH, Zang L, Peng YF, Yu BM (2005) Laparoscopic versus open right hemicolectomy with curative intent for colon carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 11(3):323–326

West NP, Morris EJA, Rotimi O, Cairns A, Finan PJ, Quirke P (2008) Pathology grading of colon cancer surgical resection and its association with survival: a retrospective observational study. Lancet Oncol 9(9):857–865. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70181-5

Culligan K, Walsh S, Dunne C, Walsh M, Ryan S, Quondamatteo F, Dockery P, Coffey JC (2014) The mesocolon: a histological and electron microscopic characterization of the mesenteric attachment of the colon prior to and after surgical mobilization. Ann Surg 260(6):1048–1056. https://doi.org/10.1097/Sla.0000000000000323

Bertelsen CA, Neuenschwander AU, Jansen JE, Wilhelmsen M, Kirkegaard-Klitbo A, Tenma JR, Bols B, Ingeholm P, Rasmussen LA, Jepsen LV, Iversen ER, Kristensen B, Gogenur I, Grp DCC (2015) Disease-free survival after complete mesocolic excision compared with conventional colon cancer surgery: a retrospective, population-based study. Lancet Oncol 16(2):161–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71168-4

Feng B, Ling TL, Lu AG, Wang ML, Ma JJ, Li JW, Zang L, Sun J, Zheng MH (2014) Completely medial versus hybrid medial approach for laparoscopic complete mesocolic excision in right hemicolon cancer. Surg Endosc 28(2):477–483. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-013-3225-8

Galizia G, Lieto E, De Vita F, Ferraraccio F, Zamboli A, Mabilia A, Auricchio A, Castellano P, Napolitano V, Orditura M (2014) Is complete mesocolic excision with central vascular ligation safe and effective in the surgical treatment of right-sided colon cancers? A prospective study. Int J Colorectal Dis 29(1):89–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-013-1766-x

Zurleni T, Cassiano A, Gjoni E, Ballabio A, Serio G, Marzoli L, Zurleni F (2017) Surgical and oncological outcomes after complete mesocolic excision in right-sided colon cancer compared with conventional surgery: a retrospective, single-institution study. Int J Colorectal Dis. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-017-2917-2

Weitz J, Koch M, Debus J, Hohler T, Galle PR, Buchler MW (2005) Colorectal cancer. Lancet 365(9454):153–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17706-X

Mori S, Kita Y, Baba K, Yanagi M, Tanabe K, Uchikado Y, Kurahara H, Arigami T, Uenosono Y, Mataki Y, Nakajo A, Maemura K, Natsugoe S (2017) Laparoscopic complete mesocolic excision via mesofascial separation for left-sided colon cancer. Surg Today. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-017-1580-0

Wang C, Gao Z, Shen K, Shen Z, Jiang K, Liang B, Yin M, Yang X, Wang S, Ye Y (2017) Safety, quality and effect of complete mesocolic excision vs non-complete mesocolic excision in patients with colon cancer: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis 19(11):962–972. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.13900

Miyazawa M, Kawai M, Hirono S, Okada K, Shimizu A, Kitahata Y, Yamaue H (2015) Preoperative evaluation of the confluent drainage veins to the gastrocolic trunk of Henle: understanding the surgical vascular anatomy during pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Hepato-Bil-Pan Sci 22(5):386–391. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhbp.205

Ogino T, Takemasa I, Horitsugi G, Furuyashiki M, Ohta K, Uemura M, Nishimura J, Hata T, Mizushima T, Yamamoto H, Doki Y, Mori M (2014) Preoperative evaluation of venous anatomy in laparoscopic complete mesocolic excision for right colon cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 21(Suppl 3):S429–S435. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-014-3572-2

Nesgaard JM, Stimec BV, Bakka AO, Edwin B, Ignjatovic D, group RCCs (2015) Navigating the mesentery: a comparative pre- and per-operative visualization of the vascular anatomy. Colorectal Dis 17(9):810–818. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.13003

Feng B, Yan X, Zhang S, Xue P, He Z, Zheng M (2017) [Anatomical strategies of Henle trunk in laparoscopic right hemi-colectomy for right colon cancer]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi 20(6):635–638

Pigazzi A, Hellan M, Ewing DR, Paz BI, Ballantyne GH (2007) Laparoscopic medial-to-lateral colon dissection: how and why. J Gastrointest Surg 11(6):778–782. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-007-0120-4

Funding

This work was supported by Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning Program (201640030), Shanghai translational medicine collaborative innovation center program (TM201701), Shanghai Shen-kang Hospital Development Centre (16CR1011A).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

Ziri He, Sen Zhang, Pei Xue, Xialin Yan, Leqi Zhou, Jianwen Li, Mingliang Wang, Aiguo Lu, Junjun Ma, Lu Zang, Hiju Hong, Feng Dong, Hao Su, Jing Sun, Luyang Zhang, Minhua Zheng, and Bo Feng have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary material 1 (MP4 219769 KB)

Supplementary material 2 (MP4 204446 KB)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

He, Z., Zhang, S., Xue, P. et al. Completely medial access by page-turning approach for laparoscopic right hemi-colectomy: 6-year-experience in single center. Surg Endosc 33, 959–965 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-018-6525-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-018-6525-1